Matthew Kerns's Blog: The Dime Library, page 29

May 27, 2021

The Man Who Made the West Wild

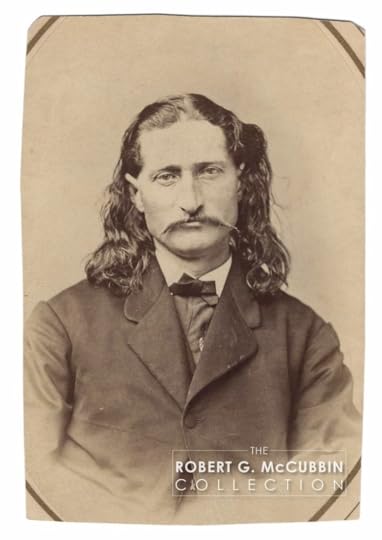

James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok was born on this day in 1837, 184 years ago.

[image error]By the late 1850s, Hickok was working for the Russell, Waddell, and Majors freight company. When this company started the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company to deliver mail and news from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, Hickok was engaged as a wagon driver, and it was during his time with the company that he met the young Bill Cody when he saved the eleven-year-old from being beaten by some older men in a camp.

When Hickok was injured in a close encounter with a cinnamon bear, the company sent him to their outpost at Rock Creek Station in Nebraska to recover while working some light duty in the station’s stables. There, the injured Hickok walked slowly and with a pronounced limp, his left arm damaged by the bear to point of being useless. In an event that has been much recorded and extremely exaggerated, Hickok, who had been left in charge of the station, went out to meet Dave McCanles, a local rough who had sold the property to the Express company and was angry about a late payment.

When McCanles, expecting to press the older and smaller station master for money was greeted at the door by the tall, quiet, and reserved Hickok, he demanded to see the other man.

“What in the hell, Hickok, have you got to do with this? My business is with Wellman, not you, and if you want to take a hand in it, come out here and we will settle it like men.”

Hickok stood for a moment before speaking, and then slowly replied,

“Perhaps ’tis, or ‘taint.”

Hickok stepped back inside to talk to Wellman when he saw McCanles move to raise a shotgun. Bill fired his own gun from inside the house, killing the man. In the subsequent moments, Hickok and the others at the station killed two more men who were with McCanles. A subsequent trial determined that Hickok was not guilty of murder based on self-defense, and Hickok left the state before friends of Dave McCanles could catch up to him. Versions of this story later appeared in newspapers and magazines after the Civil War, claiming that in the encounter Hickok had shot down a dozen members of the infamous M’Kandlas Gang. While all of the court documents refer to Hickok, whose given name was James, as William, they attach two other nicknames, Duck Bill or Dutch Bill. Some historians have theorized that he was called Duck Bill because of his thin lips. The nickname prompted Hickok to grow a mustache covering his mouth, but it wasn’t until after the war that Jim Hickok was known by only one moniker, Wild Bill.

During the Civil War, Hickok joined the Union initially as a scout and later as a wagon master in Sedalia, Missouri. When Confederate troops captured one of the wagon trains he was assigned to, he escaped to Independence, Missouri to rejoin his unit. While there, he chanced upon a saloon with a large crowd outside, and a mob that demanded the bartender’s blood. Hickok stepped in front of the saloon’s door and drew his twin pistols, demanding that the angry men walk away. When one of the men began to step forward, Hickok fired above his head, as well as the man standing next to him, the bullets passing close enough that both men could feel their hair move. Drawing back the hammers on his revolvers, Hickok had warned the crowd that he would shoot the first man to move forward. As the men dispersed a woman in the crowd had shouted, “My God, ain’t he wild!” and the name stuck.

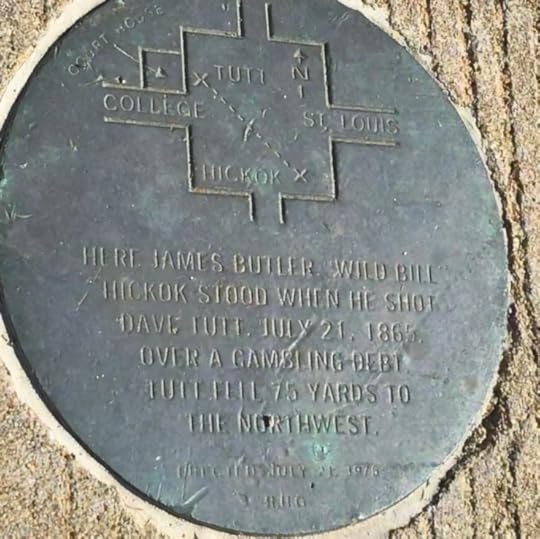

When the war ended, Wild Bill returned to Springfield. Also in the city was a man named Dave Tutt, who Hickok had encountered several times during the war. Initially, the two gamblers were friendly, but soon their relationship soured. Tutt may have started a relationship with a woman that Hickok had once courted. Hickok returned the favor by spending considerable time with one of Tutt’s sisters, prompting Dave to tell Wild Bill to leave her alone. There were rumors around Springfield that Tutt's sister was now pregnant with Hickok's illegitimate child.

Hickok refused to play cards with the man, so one night Tutt proceeded to fund every player that lost to Hickok, ensuring that they wouldn’t have to leave the table. Hickok again won, taking the money that Tutt had provided to keep the men in the game. Dave stood up to remind Wild Bill of a forty-dollar debt he owed on a horse trade. Hickok peeled the money from his winnings and handed it to Tutt. Tutt angrily continued that Hickok owed him thirty-five dollars more from a previous card game. Hickok said that he remembered that particular game’s debt being twenty-five dollars, and began to count out more bills.

Tutt reached for Bill’s Waltham repeater watch on the table and Hickok shot to his feet.

“I don’t want to make a row in this house,” spat Hickok to the other man. “It’s a decent house and I don’t want to injure the keeper. You’d better put that watch back on that table.”

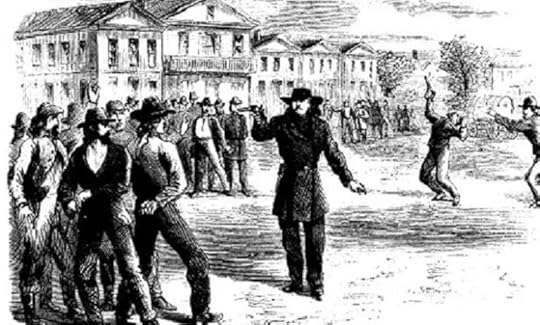

Tutt laughed and walked out with Hickok’s watch. Taking the watch as collateral on the supposed $35 debt signaled that Tutt believed Hickok a man unable to pay his debts. To accept the insult would be to admit this as truth, which would have ruined Hickok as a gambler in Springfield, his sole source of income. Several days later, some friends of Tutt’s tried to cajole Bill into a fight, telling him that Tutt planned on wearing the watch when he crossed the town square the next day. Hickok told the men to warn Tutt that this was inadvisable, warning "He shouldn't come across that square unless dead men can walk." Hickok was in the square the next day when Tutt approached holding the watch. As he began to walk across the street, he pulled his pistol, and Hickok responded by drawing his pair and firing a shot from each simultaneously into Dave Tutt’s heart. Once again, a trial ensued and Hickok was found not guilty.

This gunfight was the source of the famous “shootout at high noon” trope that has pervaded western literature and drama ever since. There are conflicting accounts that state that Hickok had actually pawned the watch at Tutt’s saloon, but warned him not to wear it as he planned on returning to pay for it. Though Hickok had been cleared of murder by a jury, many citizens of Springfield remained convinced that he was a thug. When he was summoned to Fort Riley, Kansas for an appointment as a deputy US marshal, he gladly accepted.

It was while scouting for General George Armstrong Custer that Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published an article by George Ward Nichols that presented the stylized version of the encounters with Coe and Tutt that precipitated the Wild Bill legend that was accepted by the American people, if not the James Hickok that was known to his friends. Overnight, Hickok became a kind of frontier celebrity, and it was this celebrity and this article that would send Ned Buntline west to look for gunslingers and Indian fighters and buffalo hunters to fill his own works for Eastern audiences now clamoring for this kind of tale. Indeed, this story’s success led directly to the publication of the dime novel Wild Bill, the Indian Slayer, the first of many fictionalized stories about Hickok.

In early April of 1871, Wild Bill was offered a position as marshal of Abilene. The town’s mayor was Joseph McCoy, the man who had built the stockyard and turned Abilene into the cow capital of the west. He wrote of making the choice for marshal, “For my preserver of the Peace, I had ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok, and he was the squarest man I ever saw. He broke up all unfair gambling, made professional gamblers move their tables into the light, and when they became drunk stopped the game.”

After his fight with Phil Coe in Abilene and the accidental shooting of Deputy Mike Williams, the Texas cowboys now afraid of the consequences of bad behavior and the citizens of Abilene, weary of the gamblers, prostitutes, and rowdies that descended on their town each year determined to seek out another destination for their herds. Newton, Wichita, and Dodge City all became king of the cowtowns, and Wild Bill walked away from law enforcement in Kansas. He participated in Colonel Barnett’s buffalo hunt in Niagara and then went to Boston. He traveled to Colorado to visit Charlie Utter, a friend from his days in Hays. He traveled to Kansas City where he spent time as a professional gambler. He was at the Kansas City Fair along with thirty-thousand other visitors when a number of men from Texas asked the band to play Dixie. When some locals protested, the Texans took out their revolvers. Hickok stepped forward and stopped the music, to the anger of the Texans. Despite the overwhelming numbers, none of the men were willing to fire at Wild Bill.

Several years later, an article in several newspapers throughout the country reported that Hickok had been shot and killed, perhaps by a friend or relative of Phil Coe. One paper reported that William Hickok had been corralled by Texans he had angered during his time as marshal of Abilene. Growing tired of reading of his demise, Hickok wrote to the St. Louis Missouri Democrat:

To the Editor of the Democrat,

Wishing to correct an error in your paper of the 12th, I will state that no Texan has, nor ever will “corral William.” I wish you to correct your statement, on account of my people.

Yours as ever,

J.B. Hickok

Wild Bill

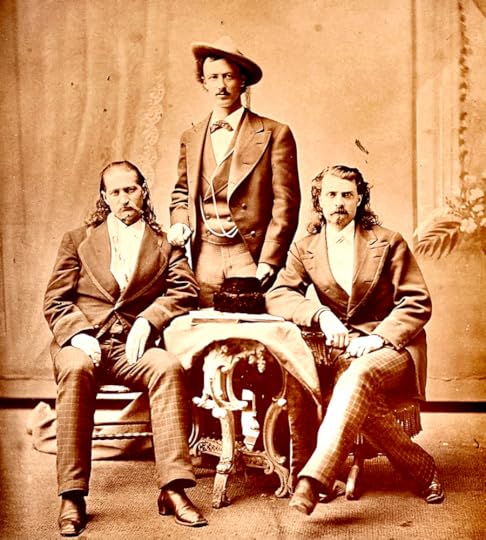

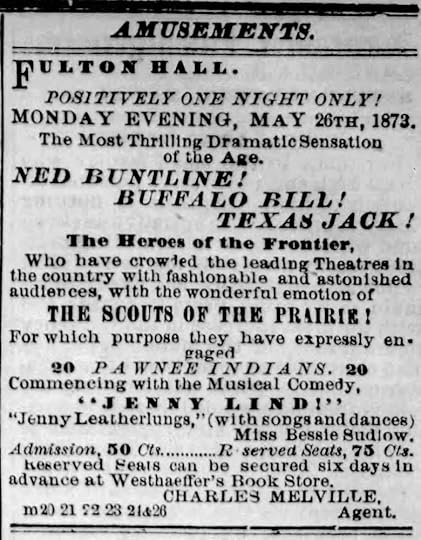

In a second letter, sent to the same newspaper on March 26th, 1873, Hickok wrote that “Ned Buntline of the New York Weekly has been trying to murder me with his pen for years; having failed he is now, so I am told, trying to have it done by some Texans, but he has signally failed so far.” With Buntline no longer a factor in joining Cody and Omohundro in their stage venture, and a lack of prospects on the western plains, Hickok agreed to give acting a shot. That fall, Wild Bill Hickok stepped off the train in New York City to join his old friends Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro in a new play, The Scouts of the Plains.

May 25, 2021

The Way Podcast

Sat down to talk with The Way Podcast about Texas Jack, the Wild West, and my new book.

https://youtu.be/_0uTL3i9PO4May 24, 2021

Life After Leadville?

Texas Jack Omohundro died in Leadville, Colorado, on June 28th, 1880 at the age of 33. He left behind his loving wife, the Peerless Giuseppina Morlacchi, who mourned him until her own death six years later. His best friend and stage partner Buffalo Bill Cody visited his grave in 1908, paying for a permanent memorial to honor his "part of the plains for life." Nine years later, Buffalo Bill passed through Leadville one last time on the way to Denver, where he died just days later.

But what if Jack didn't die there in Leadville? What if Texas Jack was simply tired of life in the public eye and made a decision to give it all up for a long retirement?

In Norfolk, Nebraska, in 1927, a reunion was held for many of the old frontier scouts, now advancing in age and having outlived men like Wild Bill Hickok and Buffalo Bill Cody. Deadwood Dick (Richard W. Clarke) was there, as was Texas Jack's old friend Lute North. Major Gordon W. Lillie, also known as Pawnee Bill, left his Oklahoma buffalo ranch to make the trip. Diamond Dick (Richard Tanner) was there for the occasion, and Doctor William Frank Carver, the "Evil Spirit of the Plains," made one final trip to the Nebraska prairie to be a part of the final gathering of the old-time scouts.

One Norfolk native, George Church, was away during the event on a trip to Hot Springs, South Dakota. When he returned, he expressed his disappointment that the great scout Texas Jack Omohundro hadn't been invited to the gathering. The July 7th, 1927 issue of the Norfolk Press carries the details:

TEXAS JACK, AGED SCOUT, STILL LIVES

Sadly, this single article is the only suggestion that Texas Jack didn't die tragically at the age of 33, but instead became an octogenarian in South Dakota. No census records or other newspaper articles support this story, so we must conclude that some handsome long-haired fellow at the sanitarium decided to yank Mr. Church's chain.

But that doesn't stop us from wondering what people might think when they hear the name Texas Jack today if he hadn't died in Leadville. Would he have reunited with his friend to form Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack's Wild West? Instead of a group of cowboys riding with Buffalo Bill to rescue the settlers from Indian attack at the end of each show, would Omohundro and Cody have fought them together, like they once did on the prairies of Nebraska? It is a shame we can never know. But we can imagine.

Diana's Review of Texas Jack

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show...

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

This is the biography we desperately needed to tell Texas Jack Omohundro's story. I first encountered Texas Jack's name while binge-reading everything I could find on Wild Bill Hickok, where Texas Jack's story is told only tangentially as part of his friendship with Wild Bill and Buffalo Bill Cody. Although Texas Jack's name isn't as prominent as it once was, his influence continues to permeate American culture, most especially (for good or for bad) in our perceptions of cowboys, the West, the astonishing changes that happened to the Great Plains and Western landscapes during the mid-to-late 1800s, and relationships between white and Native American populations.

Kerns deftly shows Texas Jack to be a complex human being--smart, strong, sunny, forward-thinking and adventurous, but also struggling with an ever-changing landscape, trying to find his footing in entertainment, and suffering from serious health issues and personal demons. Kerns uncovers many aspects of Texas Jack's history that I've not encountered in anything else I've read, creating a rich timeline for a man who managed to be part of some of the most pivotal moments in 19th Century American history. We also learn more about the people around Texas Jack, including his amazing wife, ballerina Guissippa Morlacchi, who, frankly, deserves her own book.

Although this book is a real treat for those of us who are already interested in the era and have encountered Texas Jack in other histories, it will also appeal to the general history or biography reader interested in understanding how one man's essence continues to shape our perceptions of American history.

May 20, 2021

The Cowboy, The Wizard, and the Eclipse of 1878

Eclipse glasses were sold out everywhere. Hotels along the path of totality have been booked for months. Both scientists and civilians are anxiously awaiting the moment when the moon passes in front of the sun and provides an amazing glimpse at the solar corona. People flock to the places that might provide the best views. The date could have been August 21, 2017…or July 29, 1878.

Among the young scientists, journalists, and others that streamed west to prepare for the 1878 eclipse, which cut southeast across the United States from Montana to Texas, was the thirty-one-year-old inventor from New York, Thomas Alva Edison. Edison had already achieved some prominence as an inventor for his automatic repeater and significantly improved telegraphic devices, but it was his 1877 invention of the phonograph that had provided him both fame and the nickname “The Wizard of Menlo Park.” Edison’s latest invention, the tasimeter, was designed to detect changes in the temperature of the sun’s corona, and astronomer Henry Draper had invited Edison to Rawlins, Wyoming, to test the device during the upcoming eclipse.

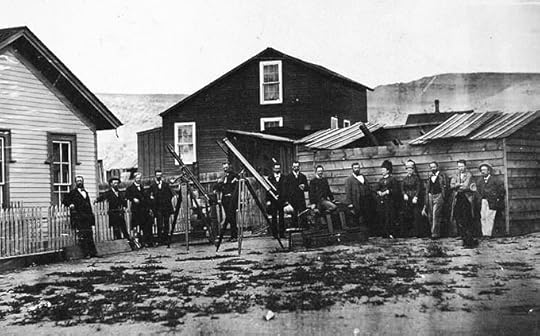

Rawlins was a rail stop founded near a natural spring. As a rail hub, it served Fort Steele, 13 miles to the east. Stage lines from Rawlins lead north towards Lander and south towards Colorado. As a rail hub located directly in the path of totality, Rawlins became the center of the American scientific world during July of 1878. The rail hub also served as a base of operations for Texas Jack, who often lead parties from Rawlins south into what is now the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forests and north into Thunder Basin National Grassland and the Big Horn Basin. Jack was also in Rawlins that July, having recently completed a series of shooting exhibitions with Doctor Carver and now preparing to lead German Count Otto Franc von Lichtenstein on a months-long trek across the wilds of Wyoming. For the facts of the meeting between Texas Jack and Thomas Edison, we’ll turn to Edison’s own journals:

"There were astronomers from nearly every nation. We had a special car. The country at that time was rather new; game was in great abundance, and could be seen all day long from the car window, especially antelope. We arrived at Rawlins about 4 P.M. It had a small machine shop, and was the point where locomotives were changed for the next section.

The hotel was a very small one, and by doubling up we were barely accommodated. My room-mate was Fox, the correspondent of the New York Herald. After we retired and were asleep a thundering knock on the door awakened us. Upon opening the door a tall, handsome man with flowing hair dressed in western style entered the room. His eyes were bloodshot, and he was somewhat inebriated. He introduced himself as `Texas Jack’ Omohundro and said he wanted to see Edison, as he had read about me in the newspapers.

Indeed, Edison and Fox tried to find Texas Jack now that they had been assured by locals, but Jack had already set out to start his trek. Edison’s tasimeter failed, though locals near Rawlins hold that he was fishing nearby with his bamboo fishing pole when he first hit upon the idea of using bamboo filament in incandescent light bulbs.

Count Otto Franc recorded in his own journal that he and Jack spent the morning of eclipse trout fishing in what is now the Medicine Bow National Forest near the Colorado border. “We caught some trout and went back to camp,” Franc wrote, “and while cooking the fish the Eclipse sets in and we have a very good view of it, Jack calls it a damned humbug and put-up job, because our tent and blankets caught fire while we were looking at the sun, we lost a blanket, burned holes in the tent and some blankets and besides burned our hands in trying to extinguish it."

May 17, 2021

The Texas Jack Combination

In June of 1876, after four seasons of touring together as The Scouts, Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro split up their show.

In some ways, their parting was inevitable. For Bill Cody, he was splitting the lion's share of the revenue three ways—one part for himself, one part for Texas Jack, and one part for Jack's wife, the Peerless Morlacchi. Texas Jack wanted to spend more of his time out West, leading parties of aristocratic and wealthy Europeans into the American wilderness. In 1874, Jack had skipped the beginning of his tour with Cody to trek across the newly formed Yellowstone Park with the Earl of Dunraven. Dunraven's book about the adventure was being read by other parties who wanted to hire Jack to guide them on their own expeditions, and Jack wanted to accommodate them.

So in 1877, Texas Jack got a late start to his dramatic season compared to his best friend, and now friendly business rival, Buffalo Bill. Bill had launched his tour in October of 1876 in his adopted hometown of Rochester, New York, and played a continuous string of performances while Texas Jack hunted and explored in Wyoming's Sweetwater, Wind River, and Bighorn ranges with Sir John Rae Reid, Chas. P. Eaton, and Samuel Ralson, son of wealthy San Francisco banker William C. Ralston. Jack didn't return to the stage until April of 1877.

Buffalo Bill had recruited as a replacement for Texas Jack a fellow scout named Captain Jack Crawford, sometimes called "The Poet Scout." On stage, Captain Jack was cast very much in the mold of Texas Jack, though his role was much more subordinate to Buffalo Bill than Texas Jack had ever been. Cody's new show was a highly sensationalized version of Cody's own encounter the previous summer with a Cheyenne warrior named Yellow Hair, who Cody had killed and scalped in an act of retribution for the defeat of General Custer at the Little Bighorn. Yellow Hair's scalp was used as a part of the act and featured heavily in the advertising of his show.

Texas Jack decided to go a different direction and change the cast of his show entirely. Larry McMurtry wrote in his book The Colonel and Little Missie that "When it came to organizing a modern theatrical troupe, Texas Jack for a time pulled ahead. He had, for one thing, his charming wife." He also had the marketing and publicity talents of John Burke, who had previously done the same job for Cody and Omohundro's combined troupe. Beyond that, Texas Jack innovated his show in ways that would ripple throughout other western shows, including Buffalo Bill's.

The first call Texas Jack made wasn't to another white frontier scout like Jack Crawford, but to a half-Cayuse "Indian scout" named Donald McKay. McKay rose to prominence during the Modoc War, where he led a group of Warm Springs scouts and proved instrumental in the eventual surrender of Kintpuash. Having a prominent Native American standing by his side proved to be a huge draw for Jack's shows. Jack also hired a trick-rider from P.T. Barnum's Great Hippodrome named Maud Oswald. Ms. Oswald met Texas Jack during the Philadelphia Centennial, where she impressed him along with a huge crowd demonstrating tricks and feats of endurance on horseback.

Texas Jack's new cast was diverse, and its diversity proved to be a winning formula. Consider the later success of Buffalo Bill's Wild West, also managed by John Burke after Texas Jack's death. Omohundro had employed the best female rider he could find—Buffalo Bill would later do the same with female shooters like Annie Oakley and Lillian Frances Smith. Texas Jack hired the most prominent Native American to stand beside him on stage—Cody would later do the same with Sioux warriors like Sitting Bull.

The response to Jack's shows couldn't be ignored, even by Buffalo Bill. When the Texas Jack combination premiered in Chicago, newspapers noted that the capacity crowd was filled not just with dime novel readers and lovers of blood-and-thunder drama, but with military brass. The highest-ranking military officials in the American West were on hand to catch Texas Jack's new show, including a grand total of 11 generals. General Phil Sheridan, General George Crook, and General George Forsyth were among this group and the presence of so much military brass rang out like an implicit endorsement as newspapers covered Texas Jack's new show. Buffalo Bill would later adopt a similar tactic, utilizing a poster showing all of the generals he had scouted for or served with, their endorsement of his show heavily implied if not made explicit.

Buffalo Bill's headstart during the dramatic season didn't seem to hurt Texas Jack's box office receipts at all. One reviewer, echoing the sentiments of the boys who came out to see the show, said "Texas Jack's play beats Buffalo Bill's play all hollow."

May 14, 2021

Buffalo Bill was Not with the Party

Even though Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill were incredibly well-known by the time they joined Ned Buntline to launch the Scouts of the Prairie show, they weren't always immediately recognizable by their fans. Newspapers at the time rarely printed images, so even when they saw notices that The Scouts were coming to their town, theater patrons sometimes didn't know exactly what to expect when they finally saw their heroes. On several occasions, such as the one below, one of the famous frontiersmen missed a show and the crowd was unaware until the end that they hadn't seen who they expected to see. As Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack toured the country over the next several years, they posed for portraits that were sold at shows and traded and collected by fans of their dime novel stories and plays alike. Soon, everyone recognized the famous buffalo hunter Buffalo Bill and the famous cowboy Texas Jack.From the Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Intelligencer Journal May 28, 1873.

There were several passages designed to be impressively sentimental and pathetic, but they were of the coarser kind, and not spun out with the finished touch of a master hand. The only moral posted was reformatory lesson successfully given by "Carle Durg," (Ned Buntline,) to "Phelim O'Laugherty," a rollicking, drunken Irishman, who reforms, becomes a man and joins the Scouts in their warfare upon the Indians.

The side scenes, or rather by-play, in which the usual songs and dances were given, were somewhat refreshing, after the din of breech-loaders and revolvers in the mimic Indian slaughter, (and the Scouts certainly know how to handle them,) but all else was common-place and monotonous.

Buffalo Bill was not with the party, having been detained by the illness of his wife. This was not known until after the curtain finally dropped, and the announcement was made. Of Course, everybody wanted to see the Hon. W. F. Cody, but as Texas Jack was on hand, they gulped down their disappointment as best they could.

May 11, 2021

Interview with Bad Things In History

May 10, 2021

A Southern Belle on the Prairie (Part 3)

As she read about Texas Jack's marriage to the beautiful, and by all accounts incredibly sophisticated, Italian ballerina Giuseppina Morlacchi, Ena Palmer consoled herself by teaching Doctor Carver how to shoot. After months of Texas Jack's tutelage, she was able to hold her own against even the finest male marksmen on the frontier. She took the lessons she learned from Jack and his friend Buffalo Bill Cody and passed them on to her dentist friend, who lived with her on Medicine Creek while working to build his own home. She recorded in her journal that Carver nearly killed her when his pistol accidentally discharged in the home, finishing the entry by saying simply that "I trust it will be a lesson for him; he is too careless with firearms."

Over time, the Doctor continued to pursue his proficiency with firearms with far more fervor than his relationship with Ena. Perhaps the relationship had been doomed from the start—though she was every bit as capable a sharpshooter as he would become, he wanted fame and she wanted a life of quiet domesticity. He wanted medals and recognition, while she wanted a home filled with the laughter of children. When he went to California to compete in a series of shooting exhibitions he begged her to come with him. She refused. He begged her to follow. She would not.

Soon, she met a man named David Coulter Ballantine. Ballantine was an established and successful businessman who could hold his own with the titans of ranching and industry, but who melted before the beautiful southern belle. He was too shy to court her, so she arranged to be camping in a tent overlooking the river just where he would pass by and see her. They sat on the bluff, looking down into the valley, and talked long into the night. When Mr. Ballantine rode away the next morning their futures were assured. They were married in early October 1875.

When Doctor Carver received the news that Ena Palmer was now Mrs. David Ballantine, he was certain he was being lied to. He bought an expensive locket with a jewel to match her eyes and boarded a train back to Nebraska. When he arrived at Medicine Creek, it is said that "one look into Ena's eyes told him that this Coulter Ballantine had satisfied the 'great want and asking of her heart.'" He placed the locket on her desk, next to a pistol that had been a gift from Texas Jack, and left.

Ena's husband was soon elected state senator, and the fortunes of David and Ena Ballantine seemed set. Ena was saddened in the summer of 1880 to learn of the death of Texas Jack. D. Jean Smith writes that "Ena reflected on the man she had once loved as she drew out of her trunk the picture that Jack had sent her in his stage costume. She had long ago put to rest the broken dreams of a life with the dashing scout, but she would never forget the buoyancy of his spirit, his quick, easy laugh and flashing dark eyes. And, yes, she could still shut her eyes and remember the easy touch of strong hands on her waist as he lifted her off her fiery little pony, Falcon."

In her chest, she kept a clipping from the Leadville Daily Chronicle noting the cowboy's death which said that:

"He was noted as a cool, intrepid Indian fighter, government scout and ranchman, but was never a desperado or even a quarrelsome man, and it is believed had no white man's blood upon his hands, unless drawn in legitimate warfare. In fact, his most intimate acquaintances refer to his kindly disposition and his exceptional muscular strength."

Ena and her husband welcomed a pair of children into their lives before tragedy struck. Her husband, returning from his duties as state senator, attempted to board a moving train and was thrown beneath the cars. He died of his injuries on October the 2nd, 1882, at the age of 39. Ena was 33, with a six-year-old son and a daughter not yet two years old. Even in the face of her loss and her grief, Ena remained convinced that she had made the right decision in marrying Mr. Ballantine. When Doctor Carver and Buffalo Bill joined forces to launch the Wild West show in 1883, she wrote "Carver is in America now and has joined Buffalo Bill in his 'play.' How thankful that I am as I am. The quiet dignity of my home life is worth a world of such as that."

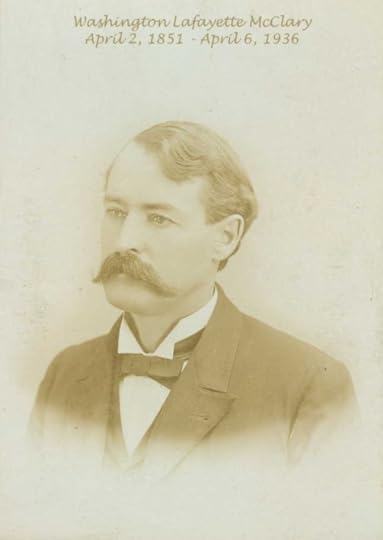

Ena turned the operation of the ranch that had been her husband over to a local rancher named Washington McClary, unaware that Mr. McClary had been secretly in love with the beautiful southern belle for years. The two grew close, and the two were married in early July of 1884, with Ena expecting their child. The two set off on a honeymoon, but on the return trip their wagon hit a rut in the road and overturned, breaking Ena's neck and killing her unborn child. Ena died days later and was buried next to her parents.

Ena's life, like Texas Jack's, was tragically cut short. Jack was 33 when he died in Leadville. Ena was 35. Despite the brevity of her often tragic life, the words she recorded in her journals have lived on, allowing historians and researchers an intimate glimpse at life on the Nebraska frontier after the Civil War. Ena's journals and the mementos she collected are a part of History Nebraska's Ballantine Family Collection. She was born Annie Palmer. She sometimes called herself Ena Raymonde. When she was riding with Texas Jack, Ena was dubbed Pa-he-minny-minnsh, or "Little Curly Hair," by a Pawnee friend of the scout. When she was married the first time she was Mrs. David Coulter Ballantine, and for just under two weeks before her death she was Mrs. McClary. But history remembers her not for the names she was given, but for the one she earned—Ena of the Plains.

May 7, 2021

I Was Accepted As Teacher

Texas Jack Omohundro became famous for the jobs he worked: Chisholm Trail riding cowboy, frontier scout, theatrical star. What isn't quite so well known is that twice in his life, Texas Jack worked another job that requires every bit as much courage as a cattle stampede, as much cunning and grit as a scout on the prairie, and as much patience and resourcefulness as a theatrical star—Texas Jack was a teacher.

It might be hard for us to picture the man so often pictured in a broad Stetson and with an assortment of rifles and revolvers at his disposal as a schoolmaster, but just after General Lee's surrender at Appomattox, John Omohundro set out for Texas. He made it to New Orleans where he caught a boat bound for Galveston, but a storm in the Gulf of Mexico capsized the ship and stranded Jack on the east coast of Florida. Here is the adventure in Jack's own words:

Once upon a time, when I was out in the interior of Florida, circumstances obliged me to seek the position of school teacher. The schoolmarm was about to retire, and I was anxious to take her place. The young idea is taught how to shoot out there promiscuously, and a he is as good as a she in teaching it. The schoolmarm was said to be of great erudition, and pronounced likely to “smash” any man at larnin’.

And while it might be strange to consider the famous cowboy teaching a bunch of rural Florida students, even here we catch a glimpse at the true Texas Jack—a cowboy, yes, but also a literate and well-read man. Here, he quotes a 1728 poem called Spring by James Thompson:

Then infant reason grows apace, and callsFor the kind hand of an assiduous care.Delightful task! to rear the tender thought,To teach the young idea how to shoot,To pour the fresh instruction o'er the mind,To breathe the enlivening spirit, and to fixThe generous purpose in the glowing breast.

Yes, our heroic cowboy sometimes quoted Shakespeare, Milton, and apparently James Thompson. Jack left Florida and finally made it to Texas, where he became perhaps the most well-known of the original Texas cowboys. As a cowboy, he earned his famous nickname, learned the language and signs of the Comanche and several other tribes, established a reputation for fearlessness and bravery, and eventually made his way to North Platte, Nebraska, where he met Buffalo Bill, became a celebrity, and eventually a star. But when he got there he worked two jobs. The first was as a saloonkeeper at Lew Baker's establishment. The second was again teaching school to the young children on the Nebraska frontier.

This time, when a group of parents asked him what he would teach he was more careful with his answer. Wary of his previous experience with the irate father and desperate for work, when one of the men asked whether he believed the Earth to be round or flat, Jack replied, “I can teach it either way you want it taught...I need the job.”

On this Teacher's Appreciation Week, I would like to send a big thanks to all of the teachers out there for all of the hard work you do. You're in rare company.