Matthew Kerns's Blog: The Dime Library, page 25

November 16, 2021

Theater Disaster

Recently, a concert in Houston ended in disaster when a mass of fans rushed the stage, trampling to death eight people ranging in age from 14 to 27. Over 300 concert-goers were treated for injuries with 25 of them hospitalized. Several are still in critical condition, including a nine-year-old boy.

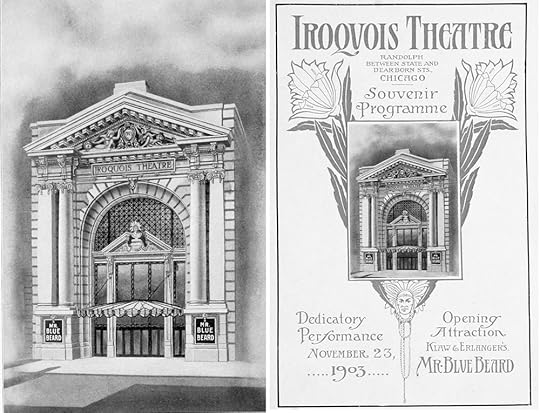

Disasters at concert halls and theaters are nothing new. An eerily similar crush of attendees occurred when the rock band The Who played Cincinnati's Riverfront Coliseum in late 1979, leaving 11 dead and 27 injured. In 2003, the band Great White was playing at a club called The Station in Rhode Island when a pyrotechnics display set fire to acoustic foam, resulting in the deaths of over 100 people. The worst theater fire in the United States happened in 1903 at the Iroquois Theatre in Chicago when the venue, advertised in newspapers as "Absolutely Fireproof," was engulfed in flame during a performance of Mr. Blue Beard. 602 people lost their lives that night, asphyxiated by the fire, smoke, and gases, or crushed to death by the onrush of other terrified patrons attempting to escape the blaze.

The following article, from the New York Herald of February 24, 1878, shows how close Texas Jack's touring combination came to a similar disaster:

During the matinee performance at the Olympic Theatre on Thursday, there was at one time almost a panic among the occupants of the gallery, but it was promptly and effectually checked by the manager, Mr. Gus Phillips, and his corps of his assistants. The Texas Jack Combination are playing at the theatre, and the crush to witness them was terrible.

It was estimated that there were fully four thousand persons in the theatre, the greater proportion of whom were boys, eager to witness the slaying of the redskins by Texas Jack and Arizona John. The gallery in which the panic occurred was the top one, and was so densely crowded that it was impossible to admit more. One boy fainted at the crush, and immediately a stampede commenced.

Mr. Phillips, the manager, with great presence of mind, pushed his way in among the boys and quieted them, but not before ten or twelve more had fainted. These were carried out to the open air, where they revived.

November 11, 2021

A Loaded Weapon

On October 21, 2021, at the Bonanza Creek Ranch in New Mexico, both cinematographer Halyna Hutchins and director Joel Souza were accidentally shot when actor Alec Baldwin fired a revolver loaded with a live round, which had been provided to him as a prop. Hutchins died from her wounds. A subsequent investigation showed that the weapon had not been thoroughly checked for safety in advance of having been handed to Baldwin, with reports indicating that a crew member yelled "cold gun" as the revolver was given to the actor, incorrectly informing him that the weapon wasn't dangerous. In the days that followed the incident, criticism was leveled against Baldwin, the movie's producers, and the film industry for its seemingly cavalier attitude towards on-set firearms in contrast to the gun control advocacy of many actors, writers, and producers in Hollywood.

Sadly, on-set tragedy stemming from prop firearms is nothing new. Brandon Lee, son of martial artist and actor Bruce Lee, was famously killed when an improperly checked .44-caliber revolver was fired in a scene from the film The Crow in 1993. In 1984, actor Jon-Erik Hexum was killed on the set of the TV series Cover Up. Hexum accidentally shot himself in the head with a gun loaded with blanks.

It's easy to blame these tragedies on poor planning, freak accidents, and even on the relative inexperience with firearms by the actors who end up wielding these weapons on set. But the truth is that horrific accidents happen even when the man holding and firing the gun is incredibly familiar with his weapon.

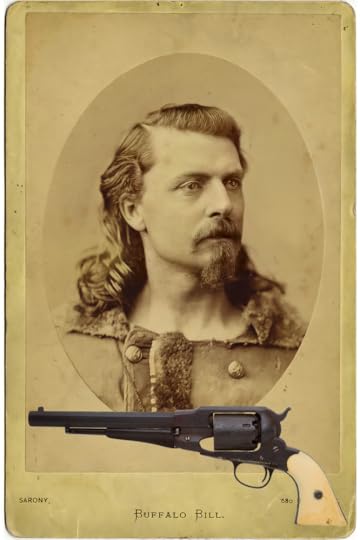

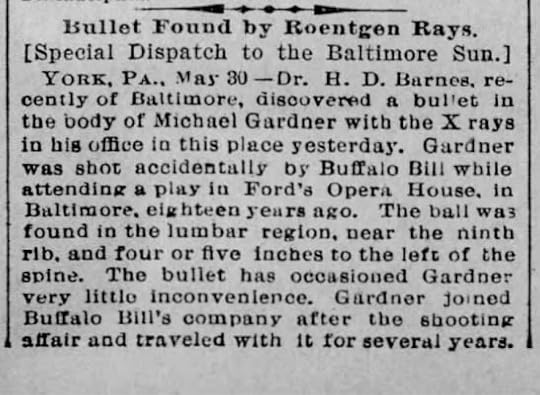

By 1878, Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro had amicably split their dramatic venture, then called the Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack Combination, into individual touring companies. On September 9th, 1878, Buffalo Bill was in the closing moments of his show May Cody, Lost or Won when tragedy struck. From the following day's issue of the Baltimore Sun.

Shot by Accident—About twenty minutes past eleven o'clock last evening Michael Gardner, aged 18 years, son of Bernard Gardner, No, 136 West Street, was accidentally shot at Ford's Opera House at the close of the performance, when Buffalo Bill, in riding up a run constructed at the rear of the stage, discharges his revolver for stage effect.

One of the barrels of the revolver was loaded last evening, and the ball, instead of passing harmlessly upward, as was intended, ricocheted from the veiling and struck Gardner, who was leaning forward over the railing in the highest tier in the theatre, in the shoulder. The curtain went down and the audience dispersed, however, without anyone suspecting that an accident had occurred, and it only became known when in company with a friend he entered a drug store at the corner of Eutaw and Baltimore streets.

There, Dr. W. H. Crim was sent for and probed for the ball, but without success. Gardner was then placed in a carriage and removed to his home. He appeared to suffer little pain and was able to walk upstairs to his room. Buffalo Bill (W. F. Cody) called at his home soon after the accident to see that he had all the attention necessary, and young Gardner chatted with him as cheerfully as if nothing had happened. At an early hour this morning his condition was very favorable.

The ball had entered Michael's shoulder and lodged in his lumbar region, near the ninth rib, between four and five inches left of his spine. Though Michael had been strong enough to walk upstairs to his room that evening and to talk to Buffalo Bill the next day, he quickly took a turn for the worse. The Baltimore American newspaper soon reported that:

The boy (Michael Gardner) who was shot in Ford's Opera House on Monday night by Mr. William F. Cody, more generally known as "Buffalo Bill," remained in the same critical condition yesterday, and the chances of his recovery are yet very slight...by direction of Mr. Cody he has been given every attention that money can provide. His father, Bernard Gardner, is a cooper by trade and is a very industrious man. Michael, like all the rest of the grown children, worked for his living. He was very fond of reading dime novels and Indian stories in boys' periodicals and worshipped Buffalo Bill as a great hero.

From his front seat in the gallery, secured by going early and waiting until the doors opened, as there was a great rush of boys on opening night, he watched the performance of the exciting drama with the deepest interest, and when the accident occurred was leaning far over the railing. Near the close of the last act there was a trial of skill between Buffalo Bill and other scouts in the troupe at shooting glass balls sprung from a trap. The rifles used in shooting at the glass balls were loaded with bullets, but the charge of powder was supposed to be so small as not to give the bullets any penetrating power, except at such a short distance as the width of the stage.

For some reason, Buffalo Bill was not fortunate in his aim on the opening night. Owing to want of practice, short-range, or the way in which the rifles were loaded, he did not strike the balls as often as was expected, and the circumstance seemed to disturb him. During the shooting, he missed six balls in succession, and misses appeared to be the rule and hits the exception. The contest was then stopped, and Buffalo Bill, mounting his pony, waved adieu to the gathered Indians and scouts and rode up an ascent representing a mountain, taking his victorious leave, as it were, accompanied by the plaudits of the encampment. As he rode up the mountain he fired two shots from the rifle with which he had been shooting at the glass balls. The two shots were fired upward. One of them did no damage, the bullet probably going into flies above the scenery, but the second one struck the boy in the gallery, entering near the shoulder and passing backward, doing through the lung and lodging somewhere in the back. The ball is so far inward that the doctors have no hope of finding it. Whenever the wound is exposed, the air from the lungs can be seen passing through it. The boy is kept under the influence of opiates, and during yesterday weakened very much.

When Cody's show moved on from Baltimore to Wilmington, North Carolina, on October 5th, Buffalo Bill wrote the boy a letter to ask about his condition.

My Dear Boy Michael,

I know you are anxious to hear from me. I would have wrote you before, but have been so undecided to know what I am going to do myself. The yellow fever is so bad I may yet come back to Baltimore and if I do then I wall arrange to send you away. If not, I will write you in a few days what to do.

I hope you are all O.K. Write me to Charleston, S.C. on receipt of this. Give my kind regards to your father, mother, and the family.

And believe me your friend,

W.F.Cody[image error][image error]

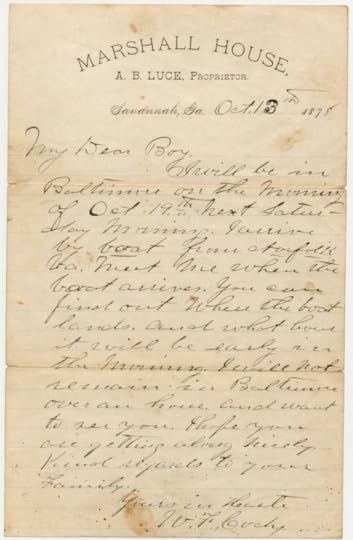

On October 13th, Buffalo Bill wrote a follow-up letter from Savannah, Georgia.

My Dear Boy,

I will be in Baltimore on the morning of Oct. 19th, next Saturday morning. I arrive by boat from Norfolk, Virginia. Meet me when the boat arrives. You can find out where the boat lands and what time it will be early in the morning. I will not remain in Baltimore over an hour, and want to see you. I hope you are getting along nicely. Kind regards to your family.

Yours in health,

W.F.Cody

During their brief hour on the dock in Baltimore, Buffalo Bill invited Michael to join him at his North Platte ranch the next month. Gardner, now firmly on the mend, happily accepted. Michael spent the next several months at Eagle's Nest, the Cody home, where he and Buffalo Bill's daughter Arta became fast friends. Michael remained over the holiday season and The Codys and Gardners exchanged letters, with Arta telling Mary (Michael's sister) that "Michael is getting very fat out here. He teaches me German and I am getting to be German too! How did you spend a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year? I had a very pleasant one indeed!"

Michael remained with the Cody family for nearly a year before returning to Baltimore to see friends and family. When the Buffalo Bill troupe returned the following year, Buffalo Bill made a point of stopping by to visit Michael and his parents. Michael then joined Buffalo Bill's show for a few seasons, now a part of the very spectacle that had caused such a grievous injury a few years earlier. Eighteen years after the bullet fired by Buffalo Bill lodged itself near his spine, Michael Gardner stopped in his local doctor's office where an x-ray revealed he still carried it. Michael lived until 1930, when he passed away at the age of 67.

November 8, 2021

Wild West Magazine's Review Of Texas Jack

https://www.historynet.com/texas-jack-book-review.htm

Historynet Staff

December 2021

Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star , by Matthew Kerns, TwoDot, Guilford, Conn., and Helena, Mont., 2021, $26.95

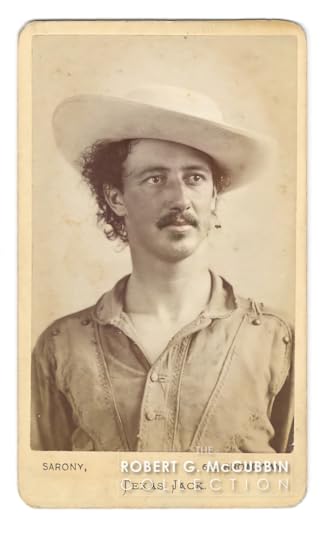

Long overshadowed by the inimitable William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro gets his due in this biography of a man who was Cody’s buddy and like Cody was a frontier scout, actor, showman, celebrity and a hero in some of Ned Buntline’s dime novels. Texas Jack was also something Buffalo Bill never was—a genuine cowboy. That, as the title indicates, is the theme for author Matthew Kerns, who manages the Texas Jack Facebook page and has written many articles about Omohundro for The Texas Jack Scout, the triannual publication of the Texas Jack Association. One big difference between the two friends—and this accounts in part for why one is far better known today than the other—is how long they were in the public eye. Cody died at age 70 in 1917; Omohundro was just 33 on June 28, 1880, when he died in Leadville, Colo., probably of consumption (tuberculosis), although pneumonia has most often been listed as the primary cause of his death.

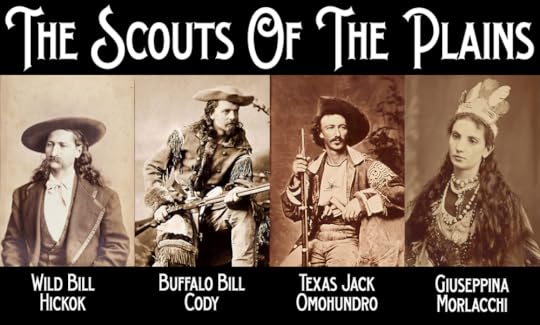

Omohundro packed a lot of living into his short time on Earth. Born in Virginia’s Fluvanna County on July 26, 1846, he served the Confederacy as a courier and scout before heading to Texas, where he first worked as a ranch cook before proving his cowboy skills to trail bosses. Fellow drovers nicknamed the likable cowboy “Happy Jack.” It was up in Ellis County, Kan., that Wild Bill Hickok told Omohundro about the money he could make hunting and scouting out of frontier forts and steered him to his friend Bill Cody. In the fall of 1869 Texas Jack caught up to future pal and business partner Buffalo Bill in North Plate, Neb. Up north, Kerns writes, Omohundro hunted with Cody, taught school and was in demand as an adviser to ranchers about cattle and cattle rustlers due to “his expertise as the best cowboy in the region.” Then along came Ned Buntline. “Texas Jack was a voracious reader and knew of Buntline’s stories of pirates and murderers and heroes,” writes Kerns, who adds it was Omohundro who pointed out the long-haired Cody to Buntline. In time Buntline would include both Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack in his dime novels and stage dramas (starting with The Scouts of the Prairie in December 1872).

While appearing with Cody, Texas Jack met Italian dancer Giuseppina Morlacchi, whom Buntline hired to play the female lead as the “Indian” Dove Eye. Cody and Omohundro pleased audiences by playing themselves, but including the beauty known as the “Peerless Morlacchi” guaranteed ticket sales. She and Jack fell in love. After having appeared repeatedly with Cody, Omohundro began to tour in 1877 without his old friend and partner, starring in such border dramas as Texas Jack in the Black Hills. Costarring in many of his shows was Giuseppina, who married Jack on Aug. 31, 1873, at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Rochester, N.Y. By the time Buffalo Bill started his famous Wild West extravaganza a decade later, Texas Jack had been dead for three years. Cody went on to achieve his greatest fame offstage while taking his Wild West on tour in the United States and Europe.

While John B. Omohundro is all but forgotten today, Kerns contends that he lives on “in every tourist who tries on a Stetson, every child playing cowboys and Indian,” as well as in every Western book, film and TV show. Clearly the author believes that Texas Jack, “perhaps the only person in Bill Cody’s life who qualified fully as a partner,” epitomizes the 19th-century cowboy. Whether you agree with him or not, the Omohundro story is one worth remembering, and Kerns tells it well.

A Typical Review

Which man would you be more excited to see, live on stage? Wild Bill Hickok, the famous gunslinger, who brought law to the most dangerous towns on the frontier? Buffalo Bill Cody, legendary scout and buffalo hunter? Or Texas Jack, the handsome cowboy showing off his skill with the lasso? You might be surprised what brought audiences out to see The Scouts of the Plains when they played the Opera House in Lockport, New York, on March 12th, 1874. A piece in the Lockport Daily News shows us which cast member typical theatergoers were most excited to see.

The Scouts At the Opera House Tonight—Great Attraction"The Scouts of the Plains" will be produced at the Opera House tonight by "Buffalo Bill," "Texas Jack," "Wild Bill," et al and will doubtless be one of the most brilliant and enjoyable entertainments given in Lockport in a long time. The above-named celebrities will be supported by a powerful dramatic company, the peerless danseuse and pantomimic actress, M'lle. Morlacchi, and the popular actor Frank Mordaunt. The Rochester Democrat in noticing the first entertainment given by this company in that city Tuesday evening says:

The sight in and around the opera house last night during the performance given by Morlacchi, Wild Bill, et al was simply astonishing. Probably the auditorium of that building was never stormed by so large a crowd of people before. We have seen it packed full, when it appeared impossible to get another person in it, but last night was certainly ahead of anything ever seen there before. hundreds went away disappointed as they were unable to get inside the door. The seats, boxes, gallery, stools, aisles, stairs, railings, and every inch of standing room were occupied. The doors on the side of the dress circle were opened, and many at once took up their position in the halls, standing on stools and peering over the heads of the audience to try to catch a glimpse of the stage.

The beauty and accomplishments of M'lle. Morlacchi are well known, and the celebrated danseuse, as usual, charmed her audience into the most enthusiastic applause. The noted artiste must be seen to be appreciated, and we advise those of our readers who have not as yet witnessed her remarkably graceful dancing and posturings to go to the opera house tonight and see her.

In the farce which opened the performance, Morlacchi had a coof opportunity of showing her peculiar talents. She speaks the Italian, French, and Spanish languages fluently, and her English has just enough foreign accent to make it pleasant to hear. In this farce, "Thrice Married," she sang one or two French songs in a splendid manner, showing that she possessed a remarkable combination of talent. It is a rare thing to see a danseuse upon whose physical strength there is a constant strain possessed of ever a fair share of vocal talent, but Morlacchi is gifted with a voice which though not of much power shows great cultivation and sweetness. The drama of "The Scouts of the Plains" is of the highest sensational order, and aside from the distinguished men who were present is but little attraction. The sight of three such men as Wild Bill, Buffalo Bill, and Texas Jack is enough to draw out a crowd. These men appear on the stage with great ease and of course bring out the scenes of border life with great power and naturalness. Their acting is very good. The physique of Wild Bill is splendid, and indeed, the same may be said of them all.

November 2, 2021

Nomadic Life

From the Omaha Bee newspaper, November 1874:

NOMADIC LIFEThe Earl of Dunraven and Texas Jack—A Three Months Hunt in the Rocky Mountains—Indians and "Grizzlies."(Correspondence of the BEE)

NOMADIC LIFEThe Earl of Dunraven and Texas Jack—A Three Months Hunt in the Rocky Mountains—Indians and "Grizzlies."(Correspondence of the BEE)CHEYENNE, W.T., Nov. 2, '74

Almost the first man to greet us when we left the Union Pacific train at Cheyenne, was the far-famed John Omohundro, or "Texas Jack." Only the day before he had returned, in company with the Earl of Dunraven, Captain Quinn of the British Army, Dr. Kingsley the eminent scientist, and a troupe of retainers from one of the most remarkable hunting expeditions on record.

The Earl of Dunraven had mapped out a route through an unexplored region, teeming with hostile Sioux Indians, and even the famous "Buffalo Bill" had declined to escort the party unless they had a strong military guard. But Texas Jack, the biggest daredevil on the plains, was more than pleased at this opportunity for adding another page to the history of a life spent in wild adventure with Indians and grizzlies.

Early in the simmer the expedition was organized, and started from New York City, with Texas Jack as guide and scout. On the 10th of July, the party left Denver, and after "taking in" Salt Lake, Fort Bridger, Corrine, Virginia City, and other places of interest, they fitted up a pack train, and from Bozeman City they started out into a mountainous wilderness filled with Indians. All the tribes were disposed to be friendly, excepting the Sioux, who frequently threatened to attack them, but they had a wholesome dread of Jack's unerring aim and the well-armed and resolute little back that were with him; and although they were frequently ordered to leave the Sioux country on pain of having their scalps taken, yet the Indians never dared fire a shot at them.

While on the Yellowstone River, Jack had a very close call. The party were following a fresh "grizzly" trail, and while riding through a thicket they caught up with the huge monster, who instantly turned and sprang towards them with a fierce growl. Jack was considerably in advance of the party, and his horse not being used to seeing such rude strangers reared and fell over backwards. The bear was quick to take advantage of the situation and springing upon the prostrate plainsman, he dealy him a blow in the breast, and another in the face, which laid him senseless. All this was done in an instant, and before a show could be fired by any of the party the animal had escaped. Poor Jack was badly hurt, and even now the cuts made by those knife-like claws are scarcely healed, and as long as he lives he will carry the imprint of that bear's paw.

A few days after this, while the party was proceeding up the Yellowstone, they saw a small party of Indians on the opposite side of the river, who were running off a lot of horses which they had stolen from a ranch further up. Jack, true to his instincts, swam his horse across the river and started in pursuit—one man after three; but the Indians were well mounted and he never got a shot at them.

After viewing the wonders of the geyser basin, the party started back for Bozeman City, where they arrived safely, everyone well satisfied and highly pleased with their nomadic life in the mountains. They brought back with them, as trophies of the chase, skins of the grizzly, and horns of the elk, antelope, and Rocky Mountain sheep, in great profusion. One pair of sheep horns weighs 41 pounds, and the elk horns were truly magnificent in size.

All of these, together with the choice assortment of mineral specimens, will be shipped across the ocean to adorn ancestral halls in "Merry England." The Earl of Dunraven was so highly pleased with American hunting grounds that he proposes to remain here some time yet; at present he goes to Canada to hunt Moose, but will return in January, and with Texas Jack for guide, he will spend several months in the Indian Territory and neighboring plains.

The tall, magnificent form, handsome face, and jovial ways of Texas Jack, together with his ornamental buckskin suit, causes him to be noticed wherever he goes, but his reputation as an Indian killer makes some persons rather afraid of him.

These persons are, however, mistaken in their man, for Texas Jack is no ruffian, but quite the opposite, and those who know him best unite in saying that he is the best-hearted fellow that ever told a story or cracked a joke, and is withal a thorough gentleman, and although many an Indian has bit the dust when the smoke curled from the muzzle of Jack's rifle, yet he claims he never harmed anyone, except in defense of life or property.

Texas Jack started for Boston last night, for although his life in principally spent as a scout, yet his home in in the East, and he showed us the picture of as sweet and gentle a face as fancy could paint, and very tenderly he said: "this is my wife."

October 29, 2021

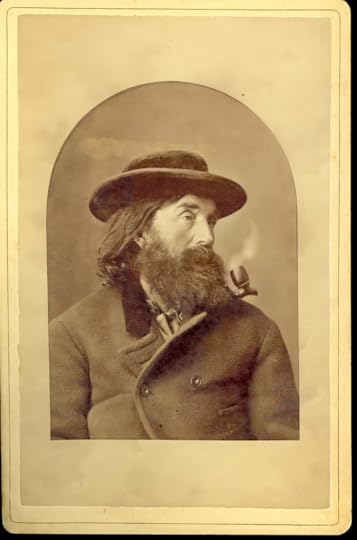

California Joe

On one of his sojourns through Kansas at the end of a cattle drive, Omohundro found himself near Fort Hays, Kansas where he met an old mountain man named Moses Embree Milner, better known as “California Joe”. Joe had been a scout in the Mexican American War, and had later been kidnapped and escaped from a band of Ute Indians. He returned home, married a thirteen-year-old beauty, convinced her to honeymoon some two thousand miles away in California where he could prospect for gold, and fathered four children with her before deciding that domesticity might not be a lifestyle he was suited for.

California Joe traveled throughout the west, prospecting in Montana and Idaho, killing men in Texas (a dispute over cards), Montana (for jumping Joe’s claim), and Virginia (for kicking his dog). In 1867 Joe was hired as chief scout for Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer on General Winfield Scott Hancock’s (known to his troops as “Hancock the Superb”) expedition. Custer was instantly taken with Joe, bemused by the funny and talkative man who smoked his briar pipe from the back of his mule as he rode in line with the 7th Cavalry’s fine horses.

In My Life on the Plains, General Custer recounts his first meeting with Joe:

In concentrating the cavalry which had hitherto been operating in small bodies, it was found that each detachment brought with it the scouts who had been serving with them. When I joined the command, I found quite a number of these scouts attached to various portions of the cavalry, but each acting separately. For the purpose of organization, it was deemed best to unite them in a separate detachment, under command of one of their number. Being unacquainted with the merits or demerits of any of them, the election of a chief had to be made somewhat at random.

There was one among their number whose appearance would have attracted the notice of any casual observer. He was a man about forty years of age, perhaps older, over six feet in height, and possessing a well-proportioned frame. His head was covered with a luxuriant crop of hair, almost jet black, strongly inclined to curl, and so long as to fall carelessly over his shoulders. His face, at least so much of it as was not concealed by the long, waving brown beard and mustache, was full of intelligence, and pleasant to look upon. His eyes were handsome, black, and lustrous, with an expression of kindness and mildness combined. On his head was generally to be seen, whether awake or asleep, a huge sombrero, or black slouch hat. A soldier's overcoat, with its large, circular cape, a pair of trousers, with the legs tucked in the top of his long boots, usually constituted the make-up of the man whom I selected as chief scout. He was known by the euphonious title of 'California Joe;' no other name seemed ever to have been given him, and no other name appeared to be necessary.

This was the man whom, upon a short acquaintance, I decided to appoint chief of the scouts.

California Joe was eventually demoted from chief scout to common scout after one particular losing battle with a whisky bottle and fell in with another scout he would quickly befriend, James “Wild Bill” Hickok. Milner would later describe Jack Omohundro as, “a pleasant man who made friends easily, a man with a smile and a joke for all, but very dangerous when his anger is aroused. During those days at Fort Hays [we] became warm friends.”

In 1874, Milner again scouted for General Custer on his expedition to the Black Hills, where Joe remained to prospect for gold when the expedition was over. He reconnected with his old friend Wild Bill in the Dakota Territory after Hickok left Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack's show The Scouts of the Plains, and was in or around Deadwood when Hickok was murdered by Jack McCall. Shortly after, California Joe was at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, where he got into an argument with Thomas Newcomb, reportedly over the death of Wild Bill Hickok. Both men drew their pistols, but California Joe convinced Newcomb to holster his weapon and have a drink. Later that day, while California Joe stood outside with a few friends, Tom Newcomb shot him in the back with a rifle, killing him.

California Joe Milner was buried at Fort Robinson, but later reintered at the National Cemetery at Fort McPherson, where his friend Texas Jack had once scouted for the Army with Buffalo Bill.

October 18, 2021

Kit Carson Jr.

By the end of Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill's second tour, they had amicably parted ways with both Ned Buntline and Wild Bill Hickok. Cody was eager to start another dramatic tour, but Texas Jack had agreed to lead the Earl of Dunraven on a trek through the new Yellowstone Park. While Jack and the Earl visited the geysers, Buffalo Bill started his tour without Jack, having hired an actor who was billed as Kit Carson Junior to tour with him. When Jack returned from his trek, he and his wife spent several weeks with Cody and his family at their new home in Rochester, New York.

In Rochester, Cody and Omohundro enjoyed leisurely strolls through town and time spent with Cody’s children without the pressing needs of theatrical touring. Ever fond of children, the two scouts spent much time interacting not only with Bill’s own daughters and young son, but with other Rochester youth. One Rochester local who was a child that summer later recalled that:

Texas Jack was always the life of the party. One day he got all the horses from the two livery stables, Black’s on Main Street near the Baptist church and Frank Wetherill’s on Chapin Street and turned them loose on Main Street. Then he chased the horses up and down the street to show people how they caught them with the lariat and other customs of the plains.

Another day Omohundro and Cody were riding through the town when they came across a dog sitting beside the road:

Jack, who had already shown us tricks on horseback with the rope, saw a dog sitting under the surrey, and offered to bet a bottle of champagne that he could ‘rope’ the dog. Buffalo Bill accepted the wager, with the understanding that the horse should be moving at a good speed. Texas Jack rode by two or three times and at the first throw of the rope it settled around the dog’s neck. Then the fun commenced. The dog being an old one and the weather being hot, the dog began to froth from the mouth and Texas Jack could not loosen the rope from the dog and at the same time was busy keeping out of the way. This caused a good deal of excitement. Buffalo Bill remarked that it was the first time he had ever seen Texas Jack caught in a trap of his own making.

Though this was initially all in good fun, things escalated when Kit Carson Junior, the actor Cody and Omohundro had hired to take Wild Bill’s part in the show when he parted ways with the company, shot and killed the dog. The dog’s owner was justifiably upset and was only calmed when Texas Jack offered him $100 to cover his loss. Omohundro never forgave Kit Carson Jr. For most of his life, Texas Jack had given much weight to his ability to judge another man the moment he met him, and his judgment of Kit Carson Jr. was a harsh one. Before he had left to hunt with the Earl, Omohundro warned Cody that the young actor was not to be trusted, and that he was only using Cody to attain a measure of fame that would allow him to make a name for himself at Buffalo Bill’s expense.

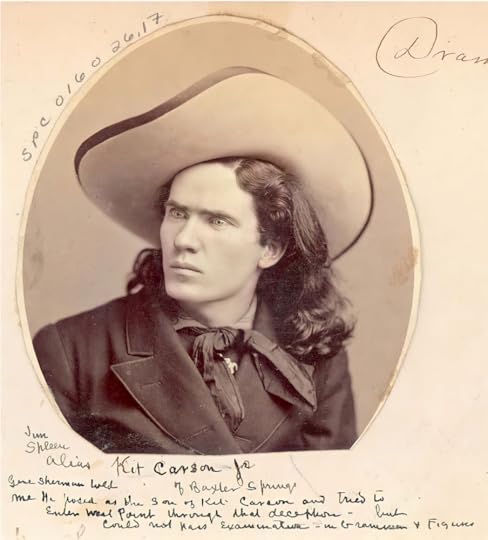

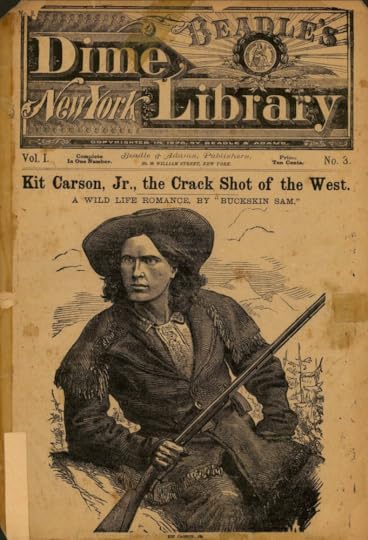

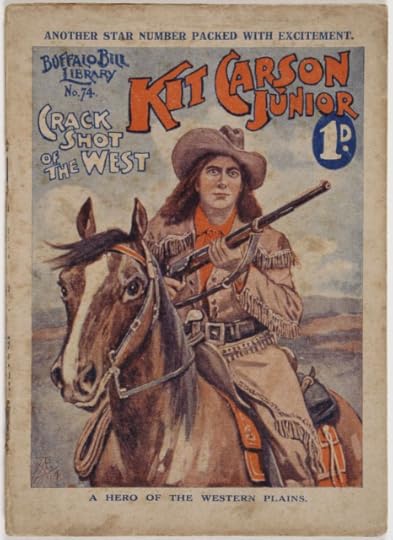

Like Omohundro had warned, Kit Carson Junior left Cody at the end of the dramatic season, attempting to establish his own western drama trading on his association with Buffalo Bill For a few years, he attempted to run his own combination, in direct competition with Cody, which upset Bill greatly. In one of his later letters to Buckskin Sam, Cody mentions that Kit Carson Jr. was arrested in Chicago for hitting his wife with intent to kill. Cody notes that “I should have expected as much.” A note on a portrait of Carson Jr. in the collection of James Earl Taylor, who used the portrait to illustrate the dime novel Kit Carson Jr., the Crack Shot of the West states that Kit Carson Junior’s real name was Jim Spleen and that he had posed as the son of the famous scout Kit Carson to try and get into West Point. According to Taylor, General Sherman had confided in him that Spleen was discovered to be an imposter when he failed to pass the entrance examinations for either grammar or mathematics.

On his own, Kit Carson Junior took to peddling Indian medicine, or snake oil, promising that the concoction he offered would remedy any number of ailments. He also lectured widely on his supposed experience with various Native American tribes and their conflicts with the ever-expanding frontier. This article, from the Bangor, Maine, Daily Whig and Courier newspaper, typifies Spleen's exploits:

It appears that "Kit Carson" has been arrested in Indiana for passing counterfeit money. It would seem as though there ought to be some punishment for his counterfeiting a good name as well as good money. We do not know whether this in the same person who was somewhat familiar in this vicinity a few years ago, and who professed to have the same name and to be a relative of the heroic scout, bit who was chiefly remarkable in this respect for his want of resemblance to the appearance and character of the original bearer of the name.

It would not be altogether surprising if such was the case, considering the appearance and the ways and manners of "Kit Carson, Jr,." and his experience, which revolved from appearances on the stage as lecturer and actor to disposing of "Indian remedies" at county fairs, and although it is not to be presumed that many credited him with actual relationship to the distinguished scout of the plains, there might have been some disrepute reflected from the counterfeit to the original.

There is no law to prevent a man from calling himself what he likes, so long as he does not use a false title for the purposes of fraud; but it would be a satisfaction if pretenders could be made to suffer for casting discredit upon honorable names to which they have no right. At any rate, if this scout of the gutters has been caught in counterfeiting more tangible property than a good name, he is likely to get his hair cut and be taught some more useful trade that delivering lectures or peddling "Indian remedies," and may consent, when he concludes his experience, to assume a more honest appelation, and to earn an honest livelihood.

The Harrisburg Telegraph expands in an article headlined "A First-Water Fraud."

Our readers will remember a tall, long-haired individual, wearing a buckskin suit and a broad sombrero, who promenaded throughout streets by daytime last week, and who "lectured" in the evening to large audiences in front of the courthouse and sold a book containing a remarkable account of his adventures in the "far West," where he was a trapper scout, hunter, and a combined edition of Wild Bill, Texas Jack, Buffalo Bill, Big Footed Ie, Snakey Wallace, and a hundred and one other buckskin heroes who figure in dime novels and kill millions of Indians, buffaloes, and other wild game and do it just as easy.

This Kit Carson, Jr., was feeling remarkably brave while here, and took occasion in the course of his "lecture" to malign the character of a certain army officer whom he pretended to have seen and known while on the plains. That he did not know him was self-evident, or he never would have spoken of him as he did.

It turns out now, on the authority of a Brooklyn paper, that this same Kit Carson Jr. is a fraud of the first water, and that he never was on the plains. That he is—heaven save the mark!—a book agent of the brassiest kind, with a tongue remarkably glib from long practice and a harder cheek to the square inch than any of his talky compeers. Kit was in a New York town the other day and after removing his long hair and buckskin suit and donning civilized habiliments he "gave himself away" in the most thorough manner, relating to a party of admiring friends how he had pulled the wool over the "Reubens" in the "country" towns by wearing his peculiar uniform and how he made lots of cash selling his book, clearing $50 in one town, $40 in another, and so on. He advised his hearers to get a book containing adventures on the border and climb into a buckskin suit, and their fortunes were made.

The true Western scout does not make an exhibition of himself, and those who come East and prate of their glorious deeds are held in supreme contempt bt the hardy, earnest fellows in the far West. And so must Mr. Kit Carson, Jr., the brassy book agent, be held.

The Army officer in question was the deceased George Armstrong Custer, who "Kit Carson Jr." routinely spoke of as both an old acquaintance and an incompetent military commander. His other speaking points were religion ("Don't be a Catholic, don't be a Protestant. Be a man."), personal behavior ("Don't lie, steal, drink, smoke nor chew tobacco, love God and man and never deceive a woman.") and politics ("Don't be a Republican, don't be a Democrat, be an American. It it were not for the whisky in the Democratic party, it couldn't live twenty-four hours, and if the thieves and liars were taken out of the Republican party it couldn't live ten minutes.")

One newspaper reported that after a lecture in Paterson, New Jersey:

[Kit Carson Jr.] went into the baggage room, took off his broad-brimmed hat, his buckskinned suit and his long-haired wig, revealing under the masquerade a bright-looking young man of the world, a shrewd canvasser. “You boys are fools,” he said to the depot folks, “to be slaving out your lives here for $40 or $60 a month. I tell you the people like to be humbugged. -- Nobody could sell this book till I took hold of it and passed myself off as “Kit Carson, Jr.,” and now I’m coining money. Last night I cleared $50 in Middletown, and tonight $35 in Paterson. I’m making big pay. Boys, there’s nothing like it. The people will pay well for being humbugged. Give up your railroad job and buy a wig, a broad brimmed hat and buckskin suit, and then take the agency for a frontier story book. You’ll get rich. Come, let’s have a drink!”

He also spoke against the American government and military, and in favor of the Native tribes. "Kit Carson Jr. says the Black Hills belong to the Indians, fair and square," reported the St. Albans, Vermont, Advertiser, "and that the government treats them badly." The lecture concluded with Carson shooting an apple off the top of his wife's head, followed by a pipe from her mouth.

Kit Carson Jr's lecturing career was short-lived. In March of 1881, the Chattanooga, Tennessee, Daily Times reported that "The alleged Kit Carson Jr.'s blathering no longer entertains the crowd of knowledge seekers who have heretofore listened to the disquisitions on his idea of how the world ought to be run, society reorganized, and religion reformed. He is languishing in the hospital with his system infected with smallpox. He evidently brought the disease with him, for it is the only case heard of in this vicinity." He died at the Read House Hotel and was buried in an unmarked grave to avoid infecting locals with smallpox.

October 11, 2021

Indians & Cowboys

In Texas Jack: America's First Cowboy Star, I make the argument that the "Cowboys and Indians" trope, so prevalent in film, literature, and America's self-created mythology finds its foundation in the spring of 1872 when real-life cowboy Texas Jack saved the life of his friend Buffalo Bill Cody in an encounter with Minniconjou Sioux warriors on the prairies of Nebraska. Buffalo Bill maintained, popularized, and enlarged this myth in his Wild West shows, where the finale of the night was a settler's cabin besieged by hostile warriors with Buffalo Bill himself riding to the rescue, not with his fellow scouts or an Army battalion, but with a group of cowboys.

The dime novels that made Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill famous depicted them as great "Indian fighters," always fighting against and prevailing over their "savage foes." These men, along with their stage costar Wild Bill Hickok, eventually became folk heroes, more akin to Paul Bunyan or Pecos Bill than the real John B. Omohundro, J.B. Hickok, and William F. Cody. And when that happened, a lot of subtlety was lost, as was the truth about their relationships with Native peoples.

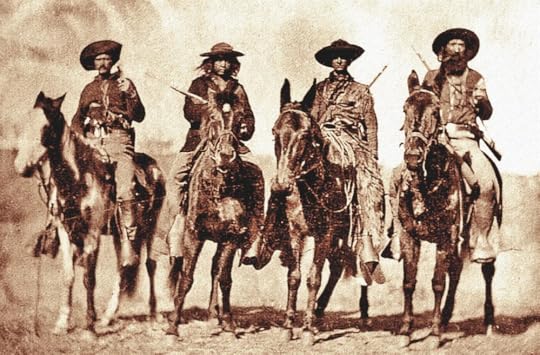

This is Pitaresaru (Chief of Men), who was the leader of the Chaui band of the Pawnee. In 1872, Texas Jack, who had spent time with Frank North among the Pawnee, learning their language and signs, was assigned to accompany the Pawnee during their annual buffalo hunt. He wrote fondly of his time hunting with Pitaresaru, who Jack called "Old Peter," and his new Pawnee friends.

While the Pawnee showed Jack how to hunt buffalo with bow and arrow, he showed them the lasso tricks he had picked up as a cowboy on the Chisholm Trail. The Pawnee nicknamed Jack ruukiraahak awikiickawarik "Whirling Rope," in appreciation for his skills. The next year, Jack was on stage with Buffalo Bill when the Pawnee were badly defeated at Massacre Canyon. Jack told reporters that the Pawnee, who he often referred to as "my tribe," were "the best Indians."

Dr. Kingsley, who hunted with Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill, remarked that“they have a sympathy and a tenderness toward Indians infinitely greater than you will find among the greedy, pushing settlers, who regard them as mere vermin who must be destroyed for the sake of the ground on which depends their very existence. But these men know the Indian and his almost incredible wrongs, and the causes which have turned him into the ruthless savage that he is, and often have I heard men of their class say that, before God, the Indian was in the right, and was only doing what any American citizen would do in his place.”

One newspaper reporter said, “Texas Jack states that the trouble between the palefaces and red skins in the Western States was caused by the thieving propensities of the former more than the shortcomings of the latter. White men steal their ponies and the Indians are never able to get justice."

Though Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack fought Minniconjou (and other bands of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe) on the plains of Nebraska, they had complex relationships with Native people. Jack claimed, and likely believed, that his prowess as a scout was in large part due to his own Native ancestry. He often told people that his family, as well as his distinctive surname, were descended from Powhattan. Omohundro, he confided to friends, was a Pawhattan word that meant "the place where the fresh and the salt waters meet."

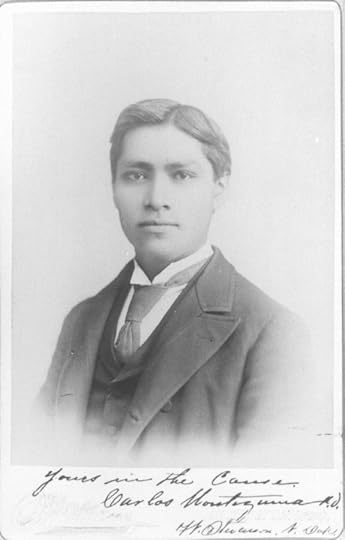

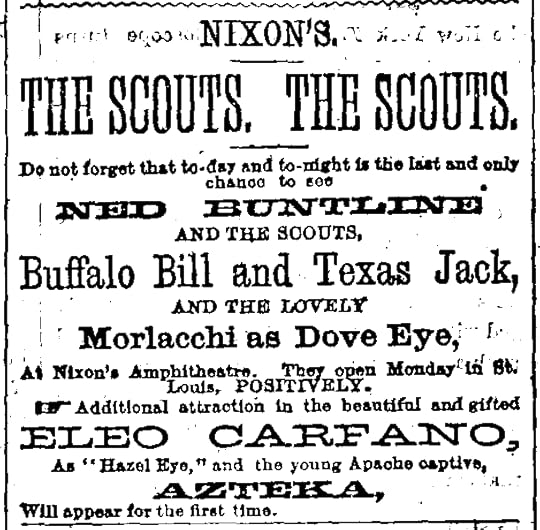

From the very beginning, Native people joined Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill on stage. When their show, The Scouts of the Prairie, made its premiere in Chicago in December of 1872, a small part was played by Carlos Montezuma, a Yavapai-Apache child who had been kidnapped by Pima raiders as a child and wound up in the care of Carlo Gentile, an Italian photographer. Montezuma, whose birth name was Wassaja, played the role of Azteka, making a brief appearance in the play’s Act III, where he attacked Phelim O’Laugherty, the drunken Irish character in the play until Ned Buntline’s character Cale Durg came to the rescue.

Montezuma and his adopted father stayed with the show for just over a month. Carlos Montezuma would go on become the first Native American man to receive a medical degree in the United States and to found the Society of American Indians. He was one of the most effective advocates for Native peoples for much of his lifetime.

When Texas Jack and Buffalo Bill split their dramatic combination, which had toured for their first four years as performers, Buffalo Bill hired Captain Jack Crawford as his costar. Texas Jack hired a Native man, Donald McKay. McKay was the son of a French fur trader and a Cayuse woman, and had already risen to national prominence as a Warm Springs scout working with the Army during the Modoc War. Donald, along with his daughter Minnie McKay, would join Texas Jack and his wife for hundreds of shows over the next four years.

[image error][image error]After Texas Jack's death, Buffalo Bill's Wild West offered many Native people their sole chance to escape the confines of their reservations. At home, their ceremonial dances and traditions were made illegal under threat of violence, but in the tents and in the big stadiums of the Wild West, there were no such prohibitions.

Bill Cody blamed most of the trouble between white men and Indians on the white men. "In nine cases out of ten where there is trouble between white men and Indians, it will be found that the white man is responsible. Indians expect a man to keep his word. They can't understand how a man can lie."

I'll leave the last words to those native men who knew Buffalo Bill and called him "Pahaska," or "long hair," and considered him a friend. Black Elk (Heȟáka Sápa) spoke of Cody's "strong heart," and reportedly was touched by his spirit of generosity. Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake) treasured a hat that Cody had given him and reportedly grew quite angry when a relative once wore it. "My friend Long Hair gave me this hat," the great Sioux chief boasted," I value it highly, for the hand that placed it upon my head had a friendly feeling for me." And Chief Red Fox (Tokála Luta) offered this great praise to his friend after his death:

"In my imagination, I can see his noble spirit winging over the lofty peak, and I bow my head in memory of one who always impressed me with kindness and compassion, and enriched me with the deeply entrenched integrity of his character."

Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack were more than folk heroes, they were real men. More than Indian fighters, they had complex and deep connections to Native people, and treasured and valued them as friends.

October 1, 2021

A Trek Out West - Part 11

Continued from A Trek Out West - Part 10.

[Dr. Ferber] 25th. We tried all our skill to kill as much game as possible to get enough meat to last us till Rawlins, having little chance to shoot something after we left the Rattlesnake Mountains. Jack and I were successful, I killed an elk buck and one mule deer doe, and Jack another one. Our ponies were so heavily loaded with the elk horn and the meat that we could not ride fast, and it was late when we reached camp.

[Otto Franc] Wednesday Sept 25 - Light fall of snow during the night clear & cool during the day. All go out hunting, L & I see only an Antelope Buck, I fire at him while he is running but miss him. Dr. killed a small Elk Jack killed a black tail Doe.

[Dr. Ferber] 26th. We left the Rattlesnake Mountains, and about noon we saw at Horse Creek four buck elks, of which Frank and I killed one and F. wounded another one. That night we camped at Sage Creek.

[Otto Franc] Thursday Sept 26 - Clear & pleasant. Break & travel through the mountains towards Lankens ranch, reach Horse creek after 1 1/2 hours ride where we see a small band of Elk in the willows on the creek; Dr. & I get off our horses & after long & tiresome crawling get within shooting distance, they are all young bucks. Dr. breaks the foreleg of one, my rifle misfires 3 times but the fourth time it goes off & knocks down a fine young buck, Lancken, who has come up, & myself butcher him quickly & then having the best horses follow the trail of the one the Dr. has wounded, after riding 1 mile we start him up 1000 yards off, he makes very good time with his 3 legs & the ground being very rocky & broken we cannot gain on him although our horses do their best. We keep up the chase for 2 miles then have to give it up as the Elk enters a chain of high & steep hills where we cannot follow him with our horses. We camp on Large Creek 15 miles from the ranch; our horses are so loaded down with meat for the ranch & with different kinds of horns that we can only make short marches.

[Dr. Ferber] 27th. About noon we reached Lanckens’ ranch, having saved our scalp. Here I have to mention that coming back through the Bad Lands one morning we found three large fresh trails running parallel and made by ponies of Indians on the warpath (no lodge poles dragging behind). The guides thought that they crossed here only one or two hours before us. At the ranch, we heard that the Bannocks had killed several white people on the Wind River at the same time.

[Otto Franc] Friday Sept 27 - Cold blowing hard. Reach the ranch at noon, the men are very glad to see us & say if we had not returned by tomorrow they would have started out after us as all the Indian tribes in the neighborhood are on the warpath & it is unsafe for a small party like ours to be out. We feast on fresh bread & potatoes & coffee, entirely disdaining meat, & inquire for news from the world. Some more travelers arrive & finally, there are 9 persons in the home which fills it quite up.

[Dr. Ferber] 28th. I did not like to sit all day long in the log house, and with Jack tried my last hunt, but did not get a shot, although a number of sheep and two big rams were seen by us.

[Otto Franc] Saturday Sept 28 - Take a short tramp to look for Deer, but do not find any, spend the afternoon inspecting Lancken's stock of horses.

[Dr. Ferber] 29th. Leaving our ponies at Lancken's ranch, L. drove us with a team of four to Rawlins. Jack, who was riding a pony, killed one antelope. This was the last piece of game we killed on our trip. I have nothing more to tell, only that we arrived at Rawlins the first of October, but half frozen to death.

After we had taken our mail we went to Fred Wolf's cozy little place where we had a glass or more of fine Rhine wine and a long talk with the kind-hearted and good-humored landlord, Fred. In the afternoon we were busy packing our trunks, order boxes for our trophies, packed and shipped them.

[Otto Franc] Sunday Sept 29 - Start from the ranch in a wagon with 4 horses, cross the Sweetwater river & stop at Muddy Gap to cook Dinner then proceed to Lands Springs where we camp.

[Dr. Ferber] 30th Sept. we found ourselves in a car of U.P.R.R. Jack and I stopped at Chicago, while Frank went right through to New York. I stayed four days in Chicago and two days at Fort Wayne to see some friends.

Sportsmen intending to hunt in that part of the Rocky Mountains I advise to write to Gus Lancken, care of Fred Wolf, Rawlins. He is certainly one of the best guides around there and is reasonable in his charges. He supplies a party of two or three with himself and another as guides, four or five saddle horses, as many pack horses, all the saddles, etc., and tents, for $12 to $14 a day; grub and bedding is not included—it does not amount to much. If he should be engaged, take "Tom Sun."

P. S.— On this trip I took the elevations as well as on the first trip but did not mention it, the average being only 6,000 feet, and the highest point in Rattlesnake Mountains 8,100 feet. In all, we hunted as gentlemanly as possible; we could have killed perhaps ten times as much.

[Otto Franc] Monday Sept 30 - It commences to rain about 4 o'clock A.M. & we get up & roll up our bedding to keep it dry. Take an early start, run part of the way along (with) the wagon to keep us warm & arrive at Bills Springs where we camp.

[Otto Franc] Tuesday Oct 1 - It was the coldest night. We have froze hard. Arrive at Rawlins at noon. Result: 1 Buffalo, 1 Wolf, 4 Elk, 10 Antelope, 1 Deer 1 Buffalo 1 Wolf 6 Elk 2 Deer 12 Antelope.

[This concludes the trek of Texas Jack, Otto Franc, and Dr. Ferber in Wyoming. Soon I'll write a piece about what happened to these men after their summer spent together hunting and traipsing across the Cowboy State.]

September 28, 2021

A Chat With Texas Jack

From The Spirit Of The Time Magazine, April 14, 1877.

The other evening, a little group sat in one of the parlors of the Hertmann House, Bowery. It consisted of Texas Jack, Signora Morlacchi, his wife, Mr. Bell, our artist, and Critic.

Mr. Bell sketched, Texas Jack and the Signora chatted, whilst Critic listened and questioned.

John B. Omohundro, better known as Texas Jack, is one of the best types of an American imaginable. Our friends, the Parisians, should see Jack, and their opinions of our men would be considerably modified. Here is a man old Dumas would have immortalized, and Ponson du Terrail made the hero of a series of novels in fifty-eight volumes.

Texas Jack has a noble and most sympathetic face, beaming with intelligence and kindness. The peculiarities of two great races are easily traced in its features. The regular and beautiful aquiline profile is French norman. His mother was a French lady, and he tells us, reputed a most lovely woman. She died when he was young, hence he does not speak her language. She had seven sons, Texas Jack is the lowest in stature, being exactly six feet high. If you are well acquainted with the portraits of courtiers of the time of Louis XIV, which the brush of Phillipe de Champagne has left in the galleries of Paris, you will at once recognize, when you see Jack, that he possesses the finest type of French face. But in the exceeding breadth of the cheekbones, the peculiar oval of the forehead, and the firmness and power of the jaw, it is evident that he has Indian ancestors. His father comes of a grand tribe, the Powhattan, to which belonged the heroine Pocahontas.

“I've seen my uncles on my father’s side,” said he. “They were all men over six feet; indeed I am the shortest of the family. It appears we degenerate in stature. My grandfather and his people were all of them six feet two and three inches. My father and his brothers were not so tall, and although I’m six feet, and my brothers are still taller, yet none of them reach six feet two inches. It is so with all Indian families; civilization does not seem to agree with them.”

Critic — What do you think will be the end of the American Indians?

Texas Jack — They’ll all be swept away, except the Cherokees. That tribe intermarries with the whites, gets civilized, and forms the finest race of men and women in the world.

Critic — You have very little faith in the Western Indians?

Texas Jack — Very little. They are so inferior to the Easterns that I imagine in a hundred years or so, they will be quite extinct. You see the best Western Indians are the few who were driven from these States by the advance of civilization.

Critic — Do you speak any of their languages?

Texas Jack — Oh, dear, yes, several. But they are really not beautiful; the perpetual recurrence of the chi and cha make them sound like chatterings.

Critic — But they are very rich in words, are they not?

Texas Jack — By no means, they are quite the contrary, very poor. They possess few words, and all these words have double, and even treble, and quite opposite meanings. Hence when they are translated they have such a grandiloquent sound. I fancy the dialects of the Eastern Indians were finer than the Western, but so much exaggerated concerning them that to read of their speeches you would think they were so many Miltons; but, I assure you, they talk very commonplace talk, and display their ignorance at every turn.

Critic — Do you recognize French or English words amongst theirs?

Texas Jack — Occasionally, and even Italian and Spanish, but those were doubtless introduced by the missionaries, and chiefly apply to articles of furniture and agriculture, borrowed from us. They also have words that sound just like English, but have a very different meaning; thus, heart means tongue, and dart eye. My opinion of their languages is not a high one at all. Indeed they are so poor that pantomime is absolutely necessary in order to supply the want of words and sentences.

Critic — What do you think of the intelligence of the Indians?

Texas Jack — Some tribes are very clever and sharp. All Indians have marked peculiarities, which are interesting. Nearly all of them are great physiognomists, and can determine your character by your face, and this with surprising ease. I inherit this.

[Here a request was made by the artist, who was taking the portrait which heads this article, for silence, and Mr. Jack relapsed into quiet idle. Meanwhile Critic attacked the Signora, and a lively conversation ensued.]

The Signora — I have been married four years to Mr. omohundro, but it seems to me as if I had known him all my life. He is very good and kind, and never angry. No, I have not yet accompanied him on any of his expeditions into the prairies. He always leaves me at home, but I want to go, and shall, I hope, be of the next party. I suppose, however, I shall have to be left somewhere on the confines of civilization. Still, I am strong, and do not mind fatigue, though I strongly object to bears and rattlesnakes.

Critic — You used to dance at the Scala, at Milan, did you not?

The Signora — Yes, I did once dance at that theatre, but I am not the Morlacchi I’m often mistaken for.

Critic — I heard you sing remarkably well last night. [In her play of Thrice Married, the Signora since Ernani, Ernani, involarmi, in a very artistic manner.]

The Signora, who is a remarkably pretty black-eyed Italian lady, with charming manners, answered, Yes, but I ought to sing better than I do. Signor Arditi, of Her Majesty’s Theatre, London, wanted me to become a singer, but I preferred my dancing. I have a strong, dramatic, soprano voice, in the style of Mlle. Tities, but I never cultivated it to any great extent. I can get along without Norma or Lucrezia. My husband can act also very well. You see he belongs to the Indian race, which pantomimes wonderfully, and also to the French, who are born actors. You will scarcely believe me when I tell you he can act Quasimodo to perfection, although he won’t play it in public. He cripples himself up to look like a hunchback, and it is a capital performance.

Critic — We can ill imagine such a superb man acting the roles of a hunchback.

The Signora — Well, he can do it. I have played Esmerelda all over the country, but never with him.

By this time Texas Jack was allowed to talk again, and we began conversing about pantomiming, a gentleman, who is well acquainted with the Italian style of pantomime, now joined us, and began to pantomime with the famous scout. “Ah! You are like my wife,” cried he. “You can only do the broad and decided gestures, but I can achieve something far more subtle. Now watch, I will repeat in pantomime anything you wish me to say to yonder Indian.” He pointed to an Indian of his company seated at the other end of the room, and both fell to talking by gestures so slight, and yet so expressive, that a long conversation was held by these means, which was afterward interpreted to us. “Now, you Italian and French people cannot do that sort of thing. You must have Indian blood in you to do it. You can only express broad passions and feelings. We can speak. Even my wife, a pantomimist by profession, and an Italian to boot, cannot do what we do. Now I will read your character and tell you the impression you made upon me at first sight, and afterward you will confess to me if I am right or wrong, and pardon me if I wound you, but remember it is your own wish to know, and so you shall.”

Texas Jack then told to us each of our characters, in so surprisingly truthful a manner, that it seemed supernatural. “That is another Indian gift, and a very necessary one to us, who have to roam the plains amongst all kinds of dangerous men. Think of the life I’ve led! I am a link between civilization and the other thing. I have to endure hardships, live amongst renegades and savages, and this is the kind of life my ancestors led for countless generations before me. Do you wonder if I possess, by inheritance and habit, some peculiar gifts indispensable to a man in my position?”

Critic — Do all Indians have these faculties?

Texas Jack — In a more or less degree. Of course they don;t all of them understand the traits of civilized men as well as I do, and, therefore, are sometimes mistaken.

Critic — Do you like acting?

Texas Jack — Yes, but I can scarcely call acting the performances I give. They however, suit my public and purpose, by giving folks some idea of savage life. I think I could act very well, and my wife, a fine artiste, thinks so too.

Critic — The Signora is an artiste of a very versatile kind, and a very charming one. You could have no better professor in the art.

Texas Jack — I’m glad you think so, for she is really a very superior woman. I first acted in Chicago, but have not much experience in the profession even now. I like the plains, and my life there best; I'm going out again soon with an English Captain. You know I was with Earl Dunraven some time ago.

Critic — Did you like him?

Texas Jack — Very much, indeed. He is a perfect gentleman, highly cultivated, and most amiable. I enjoyed the trip with him. He is so much of a man.

Critic — The scenery in the Far West must be wonderful.

Texas Jack — Beyond all power of description, grand and strange. You cannot imagine what it is like. The Yellowstone region is far more beautiful that any fairy scene in your plays here. The coloring is so vivid and surprising, that if you did not see it you would not believe it possible. The Yellowstone is one of the wonders of the earth, but there are other like places out there quite as interesting.

Critic — I suppose civilization is getting along even there, and changing things greatly.

Texas Jack — One thing to be observed is that civilization has plenty of room to stir about in there, and I guess it will take a long time to upset things generally. Some one told me that buffaloes were already decreasing. I don’t believe it. I saw, last season, herds of many thousands dashing along the prairies. The bears may diminish, by going higher up in the hills, and the snakes might, with advantage, disappear altogether. When I was with the Earl of Dunraven we shot several huge grizzly bears.

Critic — You were, then, out in the Yellowstone.

Texas Jack — yes, and a queer region it is. I can’t attempt to describe it. It is all red, pink, blue, and yellow, off rocks, and hot water springs. There’s one spot so weird and unnatural that they call it the Devil’s Dome, and the Indians declare bad spirits live in it. Near there is a pyramid seventy feet high, evidently formed by a water-spout. It stands on a level, is small at both ends, and large in the middle. It is perfectly dry, and looks somewhat like a ram standing on its head. I left my lariat one night in one of the Geyser springs, and lo! The next day I found it turned to stone. A man would be petrified in the same way, if he remained long enough in the water. The Tower Falls in the Yellowstone are splendid, over two hundred feet high, but the Grand Fall is far finer. It rushes over five hundred feet of rock. Imagine, we found a lake, twenty yards wide in circumference, of boiling water, and smelling like scalded pigs. Thousands of tons of water were hurled up from its center, to thirty and forty feet, in lofty spouts. There is little or no vegetation, and, of course, little or no animal life in this terrible and fantastic region. It is so strange that I advise everyone to go and see it, for if anyone tells them about it, they will barely believe what they hear.

Critic — Is it finer than the Yosemite?

Texas Jack — It is nothing like as beautiful. Yosemite is lovely. The Yellowstone is queer, but both are very well worth the trouble of being visited. Earl Dunraven’s book, “The Great Divide,” gives a splendid description of the place, and I can assure that the Earl deserves a high compliment on that work, which you should read. Sir John Reid and his cousin Eaton are very accomplished men, and I enjoyed being with them. They are first-rate hunters. English gentlemen of their class give a fine example of manliness by the way they come out and hunt, and discover things in the unknown parts of our continent. They bring education and science with them. I have been with several who were scientists, botanists, and naturalists of high order, as well as huntsmen.

Critic — In your last letter to The Spirit you mentioned Florida. Do you like that country?

Texas Jack — Yes, much, but it is the climate which makes its charm. It is very mild and yet not enervating. Hunting down there is good, but it is the great Mexican and Californian range which is most worth seeing. Once upon a time, when I was out in the interior of Florida, circumstances obliged me to seek the position of school teacher. The schoolmarm was about to retire, and I was anxious to take her place. The young idea is taught how to shoot out there promiscuously, and a he is as good as a she in teaching it. The schoolmarm was said to be of great erudition, and pronounced likely to ‘smash’ any man at larnin’. I addressed her a letter, in consequence, in which I used the biggest words I could think of. I styled her “honored madam” and beat heavy on “construction”, “promiscuous”, “retard”, the “affinities”, and all the ten syllables in general. The letter was profoundly respectful. The next day I was mobbed. The schoolmarm could not read my letter. The big words stuck in the throats of her admirers, and it was with difficulty I persuaded them I meant no harm. They apologized, and I was accepted as teacher.

The first day I told the little boys and girls the world was round, and the sun stood still to warm it. The children were amazed. In the evening in came the father of a promising young family, the majority of which flourished amongst my pupils. “What do you mean by tellin’ a lot of damned lies to my youngsters?” says he. “What do you mean?” cried I. “Why, you idiot, don’t you be a tellin’ of ‘em that the sun sticks stock still, and this ‘ere earth goes round him? That’s a lie, and you know it. Don’t I see the sun a-gettin’ up every blessed morning in one place, and a-going to bed in t’other, and you idiot you, you keep on a tellin’ them ‘ere youngsters it sits there all day long, contrary to evidence. You go home, young man. You are dangerous, and’ll be a-tellin’ of ‘em I ain’t their own father next, you will. Go home, young man.” With this, the irate paterfamilias bounced out of the room, sweeping his offspring before him like ducklings in a whirlwind.”

Here the Signora rose to bid us farewell, and after a few compliments to the lovely and accomplished young lady, we were obliged, much against our will, to take leave of her gallant husband. We say “much against our will,” because so fascinating is the conversation of this distinguished huntsman that it is difficult to imagine any more delightful manner of passing the time than in the company of one whose experience is so vast, and whose observation is so just and intelligent.