David Rohl's Blog

November 18, 2012

An Alternative to the Velikovskian Chronology of Ancient Egypt

Note: I am reproducing this paper here to 'fill in' a missing chapter in the early development of the New Chronology. Research on the NC began in the late 1970s when I took my ideas for a revised chronology of pharaonic Egypt to Peter James, who was at that time working on the 'Glasgow Chronology' (a modification of the chronological revision proposed by Immanuel Velikovsky). This began several years of joint research between Rohl and James which resulted in the chronological model outlined below. Subsequently Rohl and James developed independent variations of this basic model with Rohl continuing to argue for Ramesses II as the biblical Shishak, whilst James opted for Ramesses III as the pharaoh who plundered the treasures of Solomon's temple. I felt it would be useful to republish the 'first outing' of the New Chronology theory here since the original paper is difficult to find. It also serves to put the record straight about when and how the revision of the Third Intermediate Period took shape.

A Preview of Some Recent Work in the Field of Ancient History

By David Rohl & Peter James

SIS Workshop, vol. 5, no. 2, 1982/83

For some years now a number of the Society’s historians have been endeavouring to provide a new model for ancient Near Eastern chronology in an attempt to answer the criticisms levelled at Velikovsky’s work in Ages in Chaos, Ramses II and His Time and Peoples of the Sea. The original imaginative concept of Velikovsky’s reconstruction has run into serious problems with regard to the method by which the so-called ‘phantom years’ are eliminated from the conventional (and apparently extended) history of the region. Very few of the Society’s members would now be prepared to stand by the revision put forward in Ramses II and His Time and Peoples of the Sea although there is still a strong feeling that Ages in Chaos remains a true picture for the period of Egyptian history prior to the end of the 18th Dynasty.

As a result of this disquiet over Velikovsky’s later revision there grew a body of scholars whose objective was to provide an alternative method of reducing the history of Egypt by some 500 years as demanded by Ages in Chaos whilst retaining the synchronisms put forward in that volume. Some tentative steps in this direction were first made at the Glasgow Conference in April 1978, the Proceedings of which have now finally been published (SISR VI:1/2/3). Whilst it was agreed that Velikovsky’s separation of the 18th, 19thand 20th Dynasties was impossible, it was still hoped that a revised chronology for the ancient Near East could be developed with Ages in Chaos as its starting point. An incomplete model embodying this approach subsequently became known as the ‘Glasgow Chronology’.

Since the first airing of the ‘Glasgow Chronology’ much work has been done to substantiate the proposals therein (for example see John Bimson’s studies on ‘An Eighth Century Date for Merenptah’, SISR III:2 and ‘Dating the Wars of Seti I’, SISR V:1). However, in spite of this work and other more general attempts at an overall revision (see ‘A Solution for the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt’ by Phillip Clapham, SISW 4:3), little real progress has been achieved towards completion of this revision due to the immense task of reducing the chronology by such a large number of years. There was a growing feeling that such a revision, while it provided some promising synchronisms, could not be realistically achieved within the limited time-span dictated by Velikovsky’s date of c. 820 BC for the end of the 18th Dynasty.

Thus we arrive at the purpose of this communication to the membership of the S.I.S. For the last two years the writers, with the help of other historians, notably Geoffrey Gammon, have been actively pursuing yet another alternative revision – one which we hope involves no preconception based on anything which has gone before. The work has progressed slowly due to the immense amount of data that needs to be researched and collated but a new model for the history of Ancient Egypt is gradually evolving which appears to answer a great many of the anomalies of both the conventional and Velikovskian chronologies.

From the obvious interest of members aware of this research it is clear that some sort of ‘preview’ or synopsis of the revision would be of benefit to those who wish to follow up the points raised. As a result, the editors of Workshop have requested that we publish this article to serve as a guideline to the structure of Egyptian history resulting from our work. A much fuller analysis of the findings will be presented as a series of papers in the Review when the fine detail and corroborative evidence is finally collated. It will almost certainly be necessary to amend or review particular aspects of this chronology as new facts come to light and it must be stressed that the following conclusions are tentative guidelines pending completion of the necessary research – if that task can ever be concluded.

The synopsis given here will take the form of a list of points for readers to consider and check for themselves, the detailed arguments being reserved for the Review. At this stage it was felt unnecessary to provide references, footnotes and acknowledgements which, again, will find their proper place in the final articles. The list starts with the later dynasties which form the ‘Third Intermediate Period’ including the earliest unequivocal date in Egyptian history and journeys backward in time to reach the date for the Exodus proposed by Dr Velikovsky.

(A) General Considerations

(1) Eusebius (5th century AD), in his introduction to the Aegyptiaca of Manetho states:

… it must be supposed that perhaps several Egyptian kings ruled at one and the same time; for they say that the rulers were kings of This, of Memphis, of Sais, of Ethiopia, and of other places at the same time. It seems, moreover, that different kings held sway in different regions and that each dynasty was confined to its own nome; thus it was not a succession of kings occupying the throne one after the other, but several kings reigning at the same time in different regions.

Here we have an ancient writer (who quite likely had in his possession a fuller and less corrupted version of Manetho) stating his belief, from the evidence at hand, that the dynasties of Ancient Egypt were at some points in time existing side by side and contemporary to each other.

One such period of divided monarchy is specifically identified by classical sources. Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus both describe a ‘dodecarchy’ in which Egypt was ruled by twelve kings, prior to the accession of Psammetichus I (Psamtek) of the 26th Dynasty.

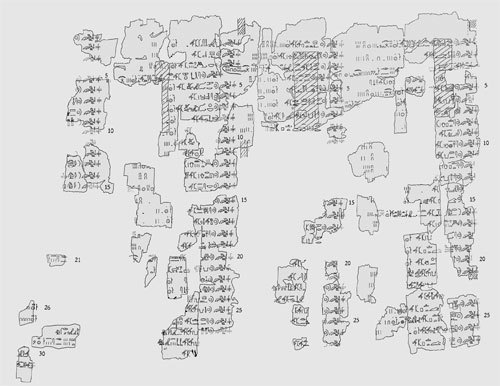

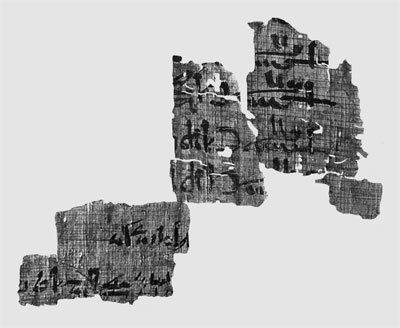

(2) The tradition of the ‘dodecarchy’ is confirmed by the considerable evidence of contemporary reigns in the Third Intermediate Period (21st to 25thDynasties). Several joint cartouches have been found on both monumental inscriptions and small artefacts, including some definite double-datings giving simultaneous regnal years of two monarchs (such as the Nile Level Texts at Karnak).

Further proof of this pattern of multiple rule is provided by war annals from the end of the Third Intermediate Period (TIP) such as those of the Assyrian invader Ashurbanipal and the Nubian king Piankhy.

(3) The anomalies (from archaeological problems to the interpretation of genealogical material) that have come to light for the later periods of Egyptian history would be sufficient to fill a volume in their own right and serve to underline the need for a revision of TIP chronology, independently of the question of external synchronisms (or lack of them) raised by Dr Velikovsky.

These three general points lead us to suggest that the most fertile ground for a shortening of Egypt’s chronology is to be found in the era know to Egyptologists as the Third Intermediate Period conventionally placed in the years 1100 to 650 BC.

(B) The Proposed Revision

(1) 664/663 BC – the starting date. The second invasion of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal and sacking of Thebes is accurately fixed by well-documented evidence from external sources (Mesopotamian and biblical chronology) and Egypt itself. The chronology of the 26th Dynasty beginning at this time is demonstrably sound (see Carl Olof Jonsson: ‘Nebuchadrezzar and Neriglissar’, appendix on ‘The Chronology of the 26th Dynasty of Egypt’, SISR III:4). The regnal years of this Dynasty known from the native records agree perfectly with the information given by the Greek historian Herodotus.

(2) The Assyrian annals describing the campaigns of Ashurbanipal list the names of twenty ‘kings’ ruling in different parts of Egypt, from which we can begin to build a chronology for the period prior to 664 BC. Ashurbanipal and his father Esarhaddon before him fought against the last two kings of the Ethiopian 25thDynasty – Taharka and Tantamani who were contemporaries of the 26thDynasty pharaohs Necho I (Niku) and his son Psamtek I (Nebushezibanni/Tushamilki). We are following here the well-established identifications of these rulers with the Necho and Psamtek of the monuments and not the erroneous suggestion of Velikovsky that these were other names for Ramesses I and Seti I – see the numerous articles in SISRrefuting his identifications.

Most of the other vassal rulers included in Ashurbanipal’s list are usually considered by Egyptologists to be local ‘mayors’ in spite of the Assyrian description of them as ‘kings’ and, most strikingly, some bear distinctly familiar royal names such as Shoshenk, Pedubast and Nimlot. We hope to show that these individuals were the later monarchs of the 22nd and 23rdDynasties whose reigns overlapped the beginning of the 26th Dynasty.

(3) From the death of Taharka in 663 BC we can back-calculate to the start of the 25th (Ethiopian) Dynasty. A slightly shorter time span for this Dynasty has already been argued by the Egyptologist Macadam, involving an overlap in the reigns of Taharka and his predecessor Shebitku from evidence on the Kawa stelae. Since the arguments against his proposals were borne largely from considerations based on the conventional chronology, there seems to be no good reason to reject Macadam’s interpretation – although his identification of Shebitku as the predecessor in question is also assumed from the conventional interpretation. Using Macadam’s approach we can reconcile the highest regnal years from the monuments with the figures given by Manetho and arrive at a date for the beginning of the Dynasty under Shabaka circa 710 BC.

(4) Working back from Necho I, we can place the earlier rulers of Manetho’s 26thDynasty contemporary with the early 25th Dynasty, the latter being based predominantly in Upper Egypt and Napata in Ethiopia. Thus Ammeris, the first king of the 26th Dynasty, reigned during the time of Shebitku and his predecessor Shabaka.

(5) It is proposed here that this mysterious Ammeris, called by Manetho ‘the Ethiopian’ was none other than Usimare Piankhy and that his invasion of Egypt in Year 20 corresponds to the end of Ammeris’ ‘reign’ in the 26thDynasty. Thus Stephinates, successor to Ammeris, was in fact Piankhy’s main adversary Tefnakhte – the prince of Sais, who following Piankhy’s return to Napata, threw off the Ethiopian domination in the Delta and became the second ruler of the 26th Dynasty. It must, however, be noted that Peter James has suggested a much lower date for Piankhy’s campaign, around 666 BC, which gives us an alternative dating for this king. This scheme will not discussed here due to lack of space but a full analysis of the two alternatives is planned for the Reviewarticles. Both views would rule out the conventional placement of Piankhy’s invasion c. 728 before the reign of Shabaka.

(6) The Stela of Piankhy’s campaign states that the ruler of Busiris, in the delta was a ‘Chief of Ma’ Shoshenk and later the ‘Chief of Ma’ Pimay. We propose that these individuals should be identified with Shoshenk III and his son Pimay of the 22nd Dynasty. Thus the last (52nd/53rd) year of Shoshenk III corresponds to the 19th/20th year of Piankhy and the earlier part of the campaign narrative.

(7) Pimay was succeeded by Shoshenk V whose reign lasted a minimum of 37 years. This would take him into the reign of Psamtek where we find the cartouche of a Shoshenk alongside that of Psamtek I. He would also be the Susinku of the Ashurbanipal vassal king-list dated to 667. (The lower alternative date for Piankhy suggested in (5) would make this Susinku Shoshenk III.)

(8) The chronicle of the High Priest of Amun (HPA) – Prince Osorkon states that he served King Takelot II from the latter’s Year 11 to 25 and then under King Shoshenk III from Year 22 to Year 39. The conventional chronology interposes 21 years between these two periods of office, on the assumption that Takelot II and Shoshenk III reigned consecutively, and is forced to postulate that HPA Osorkon lost his hold over the Thebaid and ‘disappeared from the scene’ in the intervening years. We, however, contend that Year 22 of Shoshenk shortly followed the death of Takelot in his 25th year as the inscription logically suggests. This would mean that Shoshenk III began his reign in Busiris sometime during the 4th year of Takelot II. From the structure give so far we can calculate that start of Takelot’s reign to circa 745 (conventionally 850).

(9) In the conventional chronology it would have been highly unlikely for HPA Prince Osorkon to have eventually attained the throne as Osorkon III, since he would have been at least 73 years old (assuming a minimum age of 20 years when he became High Priest, plus 14 years under Takelot, plus 39 years under Shoshenk). Adding to this the 28 regnal years of Osorkon III, he would have died at the ripe of age of 101! By eradicating the erroneous 21 years of so-called ‘exile’, his identification with Osorkon III, dying at the age of 80, becomes eminently more feasible. This is strongly supported by another piece of evidence – Prince Osorkon’s mother was Karomama Merytmut, whilst Osorkon III gave his mother’s name as Kamama Merytmut.

(10) According to Nile Level Text No. 13, Osorkon III’s 28th year corresponded to the 5th year of Takelot III. These two kings were therefore contemporaries of the 25th and early 26thDynasties. Osorkon III would be the king Osorkon mentioned on the Piankhy stela ruling Bubastis and Tanis, following the recently deceased Shoshenk III whom he had previously served as High Priest. Takelot III’s reign would therefore have fallen during the reigns of Shebitku and Taharka.

(11) The Wadi Gasus graffito concerning the God’s Wives Amenirdis and Shepenwepet gives us two reign dates which must be of two contemporary kings. The Year 19 would now belong to Osorkon III (Shepenwepet being his daughter) and the Year 12 to Taharka (Amenirdis being his sister). The date which corresponds to the event of the graffito based on these calculations would be c. 678.

(12) Going further back through the 22nd Dynasty. Takelot II was preceded by Osorkon II according to the conventional view and the available evidence seems to confirm this. However, Osorkon’s tomb, found by Mariette within the great temple enclosure of Tanis, has, since its discovery, been a subject of embarrassment for the accepted chronology. (See, for example, Velikovsky’s interpretation in Peoples of the Sea, II:ii, ‘Priest-Prince Psusennes’.) The archaeological evidence has confirmed that it was constructed prior to the adjacent tomb of the 21st-Dynasty king Psusennes I (Akheperre). In the accepted sequence of kings this would seen to be a complete impossibility, since the conventional chronology allows no overlap between the 21st and 22nd Dynasties and has Psusennes I reigning some 140 years before Osorkon II. It is our suggestion that Osorkon II did in fact reign as a contemporary of the 21st Dynasty and that Psusennes I (Akheperre) followed him as ruler of Tanis in the mid-8th century BC (rather than the conventional dates of 1039-991 BC).

(13) The presence of a ruler called Osorkon in Tanis at this time could finally resolve the problem of the identity of Osochor, 5th king in Manetho’s 21st Dynasty. To add weight to this hypothesis we find objects bearing the name of Amenemope (4th ruler of the 21stDynasty) in the burial regalia of Osorkon II’s young son Harnakht who died prior to his father. Our revision would also explain this anomaly as Amenemope was the predecessor and contemporary of Osorkon – the latter reigned for a minimum of 23 years, for the last six of which he occupied the Tanite throne as Manetho’s Osochor following the death of Amenemope.

(14) There is absolutely no clear evidence to determine which of the two Psusennes of Manetho’s 21st Dynasty correspond to the kings Akheperre Psusennes and Tjetkheperre Psusennes of the monuments. The assumption has always been that as the latter was the father-in-law of a Libyan king Osorkon then he must be the last king of the 21st Dynasty, which according to the accepted scheme preceded the Libyan 22nd Dynasty. Another fallout of the conventional chronology has been that the king Osorkon in question, whose prenomen isn’t known, must have been the first Osorkon (Sekhemkheperre) of the 22nd Dynasty. Our revision, based on a substantial overlap of the two Dynasties, makes these assumptions unwarranted. The Osorkon who married the daughter of a Tanite pharaoh Psusennes becomes Osorkon II. With Osorkon II placed after Amenemope we find a far more satisfactory solution in suggesting that Tjetkheperre Psusennes was actually the first of that name in the dynasty and father-in-law of Osorkon II. Thus Akheperre Psusennes would now become the last king of the 21stDynasty explaining why his tomb was constructed after that of Osorkon II. (Needless to say, this means that all the data normally attributed to the supposed long reign of Akheperre should be assigned to its rightful owner – Tjetkheperre, who now becomes the Psusennes I of Manetho with the 46-year reign.)

(15) Where we place Shoshenk I (Hedjkheperre) and Osorkon I (Sekhemkheperre) in this picture is as yet a matter for further study but it is interesting to note that in the Serapeum at Sakkara the Apis bulls buried during the reign of Ramesses XI were followed by an Apis burial in Year 23 of Osorkon II, with no interments from the 21st and early 22nd Dynasties! It is therefore conceivable that Osorkon II shortly followed the end of Ramesside 20thDynasty and was the first Libyan monarch to be recognized in the ancient capital of Memphis. Accordingly, this Osorkon may have reigned before his ‘predecessors’ in the conventional chronology, Shoshenk (I) and Osorkon (I).

The list of Memphite priests of Ptah places Shedsunefertem, a contemporary of Shoshenk I (Hedjkheperre), shortly after the time of the last Psusennes. This would possibly place Shoshenk I in the late 8th century. Thus we have not excluded Velikovsky’s suggestion that Hedjkheperre Shoshenk was the Pharaoh ‘So’ who took tribute from Hoshea of Israel in 725 BC (see Ages in Chaos, iv: ‘Shoshenk’).

(16) The pharaohs of the 23rd Dynasty and others of this period fall within the time span commencing with Osorkon II and ending with the reign of Psamtek I. Their placement, as in the conventional chronology, is dependent on that of the contemporary 22nd and 25th Dynasties. There is no need to detail the arguments here as their occupation of royal office does not affect the overall results of the scheme presented in this article.

(17) We now come to a ‘grey area’ in the revision which is still to be fully developed.

According to our arguments so far, the reigns of Tjetkheperre Psusennes (21stDyn.) and Osorkon II (22nd Dyn.) would have begun circa 800 and 760 respectively. In order for our 19thDynasty synchronisms to link it would be necessary to postulate a short overlap of the Third Intermediate Period into the 20th Dynasty. The later Ramessides of the 20th Dynasty may have continued to reign into the period of Dynasties 21 and 22, up to either the beginning of Psusennes I’s reign or Osorkon II’s. This explains why the kings of this period claim to be ‘sons (sons-in-law?) of Ramesses’ and the extraordinary political situation that arose near the end of the 20th Dynasty. Documents of the period indicate the existence of an unstable government including the robbing of royal tombs, revolts amongst various factions within the populace and even a war within the high-priesthood.

Such an overlap may have been considerably shorter if we take into account other unknown factors in the chronology of this period such as:

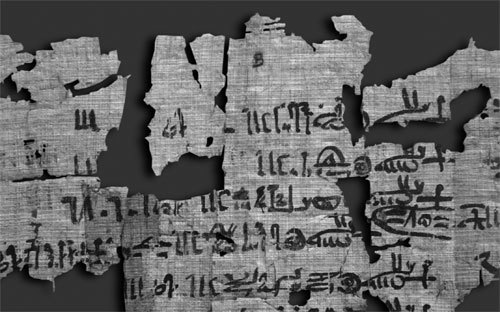

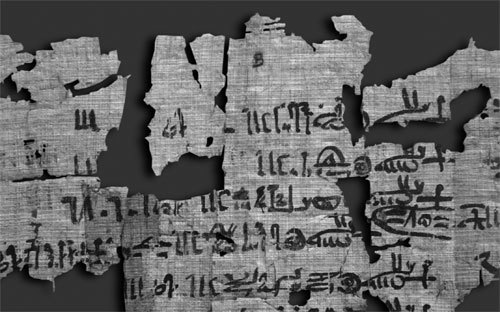

(a) The length of the interregnum between 19th and 20thDynasties, as described in the Papyrus Harris.

(b) Whether the so-called ‘Renaissance’ era at the start of the early 21stDynasty began under Ramesses IX or XI.

(c) Uncertainties in the internal chronology of the 20th Dynasty itself.

(d) Our alternative placement for Piankhy which could, of course, lower the date for the beginning of the TIP by some 20 years.

In any case, our provisional date for the beginning of the 20th Dynasty under Setnakht would fall around the beginning of the 9th century BC, and the successors of Merenptah in the latter part of the 19thDynasty would occupy the last quarter of the 10th century BC.

(18) The famous ‘Hymn of Victory’ of Merenptah (‘Israel Stela’), which states that ‘Israel is desolated and has no seed’, is now dated to only a few years after the sacking of the Temple of Solomon and the division of the monarchy.

(19) We now come to a major conclusion of our work – that is the true identity of Pharaoh Shishak. The Temple of Jerusalem was stripped of its treasures by the most famous of all the Egyptian kings who campaigned in Palestine – Ramesses II.

Considerable evidence seems to support this identification, some of which is summarized in the following points:

(a) An abbreviated form of the name of Ramesses II has been handed down to us by the Egyptian scribes, especially through documents relating to Palestine. This ‘nickname’, Sessy-[su], derived from the latter part of his nomen, was attached to the name of fortifications on the route to southern Palestine via Sinai and the city known as ‘Simrya of Sessi’ in northern Syria. The story of ‘Sesoosis’ in the works of Diodorus Siculus, and the parallel history of ‘Sesostris’ in Herodotus, clearly refer to Ramesses II and confirm the usage of this abbreviated form of his name in the ancient world.

(b) The Massoretic text of the Hebrew Bible we have today was transcribed by rabbinical scholars in the Middle Ages, who added ‘pointing’ to indicate vowel sounds and to differentiate between the sounds ‘sh’ and ‘s’. It is therefore quite possible that the name ‘Shishak’ could in fact be read ‘Sisak’. Moreover most of the vowels in ancient Egyptian writings, as in early Hebrew, were not indicated. As a result the names S-ssy-[su] and Sy-s-k are almost identical.

(c) Although the Bible only gives the usual ‘pharaoh’, Talmudic sources state that it was ‘Shishak’ who gave his daughter to Solomon as a wife. If this statement is accurate, it only needs a simple calculation to show that Shishak would have had to reign for some 40 years in order to have been king before year 10 of Solomon and still king in year 5 of Rehoboam. Neither the conventional candidate for Shishak, Shoshenk I (21 years), nor for that matter Velikovsky’s suggestion of Thutmose III (sole reign of 33 years following his suppression by Hatshepsut) would fit the long-reigning ‘Shishak’ as well as Ramesses II, who reigned for 67 years.

(d) During excavations at Byblos in Lebanon the tomb of a king Ahiram was discovered and amongst the funerary objects were found items with the cartouche of Ramesses II (see Ramses II and His Times, iii, ‘The Tomb of Ahiram’). Is it merely a coincidence that, during the reign of Solomon, the ruler of Tyre (whose domains almost certainly included the city of Byblos at this time), was a king Hiram?

(e) At the battle of Kadesh in Ramesses’ 5th year his almost vanquished army was rescued by a troop of soldiers referred to as the ‘Nearin’. In Hebrew this name (naarim) was given to a chosen group of young men formed as a fighting force of elitist troops, particularly in the early days of the Hebrew Monarchy. It would be interesting to picture the saviours of Egypt as the young men of Solomon’s Israel. This would have given Ramesses good reason to offer his daughter in marriage to the king of the Hebrews – the ally whose naarim had saved Ramesses II from the embarrassment of complete defeat at the hands of the Hittite king Muwatallis.

(f) Solomon’s Egyptian wife may well have been Bint-Anath, favourite daughter of Ramesses II by his second wife. Bint-Anath’s Semitic name – unparalleled for a daughter of Pharaoh – and her rank as ‘Great Consort’ could support the suggestion that Bint-Anath was the Egyptian princess given to Solomon with the destroyed city of Gezer as her dowry. In which case Bint-Anath may have been the Athyrtis, chief daughter of Sesoosis who encouraged her father’s conquests, mentioned by Diodorus Siculus.

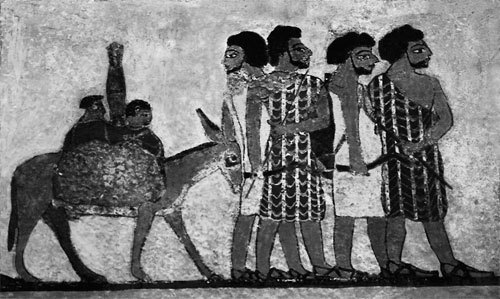

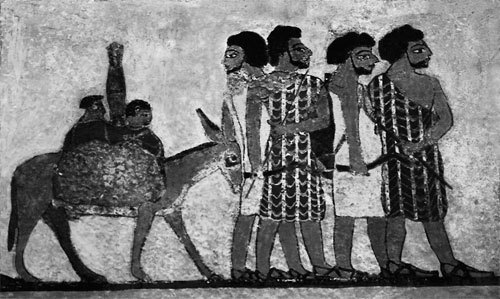

(20) The habiru of the el-Amarna period and of the reign of Seti I now take their rightful place in history as the Hebrews, who in this reconstruction were the Israelites under Saul and David. Recent studies of the habiruin Palestine have shown them not to be an invading force from outside the region (such as Joshua and the Israelites at the time of the Conquest), or marauding nomads (as with Velikovsky’s Moabite tribes), but a populace already established in some urban areas with a growing measure of political control. The situation in Palestine depicted in the el-Amarna letters fits extremely well with the rapid extension of Hebrew domination (though they had already been long present in Canaan) in the time of king Saul. In particular, the activities of the habiru armies have been compared with the escapades of the young David and his band of followers, who changed allegiance between the Philistines and the kingdom of Saul as political fortunes dictated.

Various detailed links could be added, including the complaint of Adbi-Hiba of Jerusalem (who in our reconstruction would be one of the last rulers of the Jebus before its capture by David), in his letter to the Pharaoh Akhenaten, that various cities had gone over to the habiru, including Bethlehem, the home of David. Or the fact that in both the el-Amarna letters and the biblical account of Saul’s reign Beth-Shan was in the hands of troops from the town of Gath (Philistines).

(21) The 18th Dynasty in Egypt now occupies the time of the later Judges of the Bible, whilst the Hyksos dynasties ruled during the Conquest and early Judges period.

(22) There is no need to extend the Second Intermediate Period beyond the duration already assumed in the conventional chronology (from such sources as the Turin Canon). The revision proposed by Velikovsky, of course, requires a doubling of the Hyksos period to some 400 years in order for his 18th-Dynasty synchronisms to fit with the Solomonic era. Likewise the Late Bronze I period (linked with the beginning of the Judges/Hyksos era and the early Hebrew Monarchy) need not be stretched to the length originally suggested in John Bimson’s revised stratigraphy. Several lines of evidence suggest that the Second Intermediate Period should be shortened rather than extended.

(23) Velikovsky’s date for the Exodus remains located at the end of the Middle Kingdom just prior to the Hyksos invasion circa 1450 BC. We therefore retain Velikovsky’s identification of the Hyksos with the invading Amalekites at the time of the Exodus.

This revision, of course, is concerned largely with internal Egyptian chronology and does not take into consideration the problems of Assyrian and Babylonian chronology. Work is at present under way in these fields to overlap the reigns of the Assyrian kings in order to synchronize the el-Amarna Period with the time of Ashuruballit I. Although the task is a difficult one, some promising indicators are coming to light which make us hopeful of a satisfactory solution, certainly more so than within the shorter revised chronology proposed by Velikovsky given the constraints of Assyrian chronology. It is also noteworthy that the revision suggested here accords extremely well with the uncalibrated radiocarbon dates for the Egyptian New Kingdom which are on the whole too high for the Velikovskian model, and too low for the conventional chronology.

Finally, we would like to remind the reader, once more, that the above proposals are very much the result of speculative ‘work in progress’ and subject to reassessment – we hope, all the same, that this synopsis may stimulate discussion and criticism from other members of the Society working in the field.

Published on November 18, 2012 01:53

September 27, 2012

The Origins of the Aramaeans and their Emergence in the 12th Century BC

This is a difficult topic which you are unlikely to have come across, but it has implications for biblical studies and the origins of the Hebrew Patriarchs. Though written in 1988 as an essay for my degree in Egyptology and Ancient History, and therefore written from within the Orthodox Chronology, you may see implications for the New Chronology in this little-studied area of historical research.

Introduction

It will be my intention to try to show that the historical material on which the theories of the so-called Aramaean movements of c. 1200 to c. 900 BC are based is open to an alternative interpretation. I will attempt to argue that the standard 'invasion' hypothesis is not impartially based on the available evidence but rather on a desire to see the rise to political power of the Aramaean states as part of the general population disturbances and movements thought to have taken place at the end of the Late Bronze Age.[1]

The basis of my argument will be the assumption that the Aramaeans are at least linguistically and probably ethnically related to their precursors in the Levant whom the Egyptians and Hittites called Amurru – the biblical Amorites. Albright makes the clear statement that 'The descendants of the Amorites became Aramaean, a process doubtless facilitated by close dialectal similarities'.[2]

Indeed, I am going to propose that they are basically one and the same peoples, although not absolutely equal in definition. Thus the status of Aramaeans may be in some ways similar to that of the Habiru of the el-Amarna period – that is to say, just as all Habiru were SA.GAZ but not all SA.GAZ were Habiru, so not all Amorites were Aramaeans, for they also consisted of Jebusites, Sutu and other related tribes or groups. Alternatively, 'Aramu' may have gradually evolved into a general term similar to the modern 'Arab' which today represents many very different social and tribal groups under the one banner.

The separate identities of Amorites and Aramaeans, as espoused by the standard works on the subject, have often been blurred. Where the Old Testament refers to king Hadadezer, the contemporary of David, as an Amorite, Albright prefers to call him the 'king of the Aramaeans of Zobah'.[3] Clearly there is little to differentiate the two in the minds of some scholars and perhaps we would be wise to consider the possibility that the Aramaeans were indigenous to the Levant almost from the beginning of the historical period, clad in their earlier Amorite disguise, rather than newcomers arriving in northern Syria and northern Mesopotamia at the beginning of the Iron Age.

Amorite/Aramaean Territorial Geography

In the Old Testament the Amorites are described as principally occupying the highland areas of the Levant. In particular, they are located in the region north of the Sea of Chinnereth and east of the Orontes, as well as to the east of the Jordan and, to a degree, in the mountainous region between the coastal plain and the Jordan Valley. In the lowlands, that is to say the coastal plain and the Jezreel and Jordan Valleys, the principal ethnic population was apparently Canaanite:

The Amalakites dwell in the land of Negeb; the Hittites, the Jebusites and Amorites dwell in the hill country; and the Canaanites dwell by the sea, and along the Jordan. [Numbers 13:29]

In Numbers 21:21-23 Joshua's invasion of Trans-Jordan is against the Amorites, and in Joshua 7:7 the city of Ai appears to be an Amorite possession. Also in Joshua 10:5, the Jebusite king of Jerusalem is named as one of the kings of the Amorites. According to Kenyon:

The Jebusites would seem in other references to be comprised within the Amorites, for the king of Jerusalem, a town specifically Jebusite in Joshua 15:63, is one of the kings of the Amorites who banded against the appeasing Gibeonites as described in Joshua 10:5, ... [4]

A few centuries later, we find the Aramaeans occupying the same regions all but one – the newly conquered land of Israel, south of the Jezreel, which was now occupied by the Hebrews. One extra area is added to their sphere of control and that is the north Syrian region including the Khabur Triangle. However it could be argued that this territory was also occupied by the Amorites in earlier times, but, because of its geographical remoteness from the area of the Conquest, it was not listed amongst the Amorite possessions in Numbers 13. Brinkman agrees that:

By the middle of the eighth century the Aramaeans were dispersed over an area roughly equivalent to that occupied by the Amorites at their height.[5]

Somewhat more emphatically he adds:

Even a superficial glance at the geographical distribution of the Amorites in the early part of the second millennium and a comparison with the areas occupied by the Arameans in the second half of the eighth century will show that they inhabited many of the same regions in Syria, along the middle Euphrates, and in southeastern Babylonia. ... Since there is no substantial evidence for the Arameans coming into this area in the intervening period and since there is no trace of an older Babylonian or Amorite population being displaced, one is led to wonder whether the southeastern Arameans might not be either remote descendants of earlier Amorites or at least a group speaking a related West Semitic language.[6]

Dates of first appearances of the various Aramaean/Amorite groups in the accounts of the major civilizations

Early Biblical References

Some scholars suggest that the mentions of Aramaeans in the Old Testament, in particular in the Pentateuch, are anachronistic. There, for example, Abraham is referred to as 'the wandering Aramaean' [Deuteronomy 26:5]. We also find Amorites occurring in the Mari texts (c.1800) whose nomenclature closely resembles that of the patriarchal period familiar to us from the Old Testament. The term 'Sutu' (see below) is also attested in the Mari archive.

An interesting theory regarding the origins of the Amorites was proposed by Clay in 1919.[7] According to him, the name 'Uru' appears to be associated with the principal early deity of the 'Am-urru';[8] he then goes on to assert that the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur was named after this deity. In Aramaic the name 'Amurru' is written 'Uru' and is identical to the writing of the city name of 'Ur'. The logic of his argument continues with the biblical story of Abraham's links to that city and hence the Amorite origins of the Patriarchs. The name Uru-shalim would also have a satisfactory explanation in the context of an Amorite/Jebusite kingdom in the Judean hills.[9] The early god of Amurru was also, according to Clay, variously called El-Ur/Amar/Mar of which the first gives us another obvious patriarchal link and the last the name of the city of Mari.

Whether or not Clay was near the mark with his hypothesis (without a knowledge of early Amorite religion and language I am unable to take issue with him), it is superficially at least an elegant scheme which appears to add some credence to the Old Testament traditions concerning the origins of the Patriarchs.

Later, in the monarchy period, king David (c. 1000) overthrew Hadadezer king of Zobah when the latter was occupied trying to retrieve land captured presumably by the Assyrians near the Euphrates [2 Samuel 8:3]. This victory led to the absorption of Aram-Zobah into Israelite territory, much of which was then lost again under the rise to power of Rezin king of Aram-Damascus (contemporary of Isaiah). Again I stress that Albright regarded Hadadezer as an Aramaean. We therefore meet the Aramaeans in Palestine at the turn of the 10th century, but their occupation of the area may be extended backwards in time for an undetermined period on the grounds that Hadadezer was in the act of recovering his domains from aggressors in the north when David attacked. Hadadezer was not therefore in the act of arriving in the region for the first time. Thus the beginning of the 10th century must act only as a terminus ad quem for the arrival/appearance of the Aramaeans in Palestine.

Early Mesopotamia

From early Mesopotamian sources we hear of a group of people known as the 'Sutu' who are in later times often associated with the so-called Aramaean movements. Brinkman confirms that:

Their distribution in time and place roughly matches the distribution of the contemporary Arameans, and one is led to suspect that in Babylonian parlance the terms 'Sutian' and 'Aramean' may not always have designated distinguishable groups.[10]

According to O'Callaghan, the Sutu are recorded as being desert nomads in the reign of Rim-Sin of Larsa (c. 1790 BC).[11] Brinkman also notes the first rather puzzling occurrence in this reign of the institution of the nasiku (tribal chieftain) which regularly occurs in association with the much later Aramaeans.[12] The first clear and unequivocal reference to the nasiku is otherwise dated to the reign of Ashurnasirpal II c. 870 BC. One must then ask the question: should these Aramaean associations also be regarded as anachronistic, just as is argued for the early biblical references dated to the same 18th-century period?

Egypt

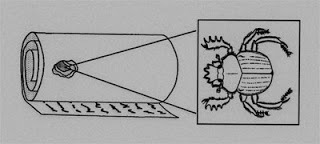

In the Egypt of the 18th Dynasty we find the pharaohs in correspondence with a country called Naharaim/Mitanni. The Amenhotep III heart scarabs of Year 10 (c. 1380 BC) commemorate the marriage of the king to a Mitannian princess. One inscription reads:

A marvel brought to his majesty, the daughter of the king of Naharaima, Shutana, the princess Gilukhepa and women of her harim numbering 317.[13]

The terms Naharaim and Mitanni appear to be interchangeable in the Egyptian texts, both names possessing the hill-country/foreign-land determinative. However, 'Mitanni' is primarily used in association with the king of the country or his envoys, whereas 'Naharaim' is predominantly the term used to describe the geographical region across the Euphrates. The term 'Mitanni' probably therefore has a narrower, more political connotation and direct connection with the Indo-European ruling class.

The country of Mitanni and therefore Naharaim was centred on the Khabur Triangle at around 1350 BC, as was the Aramaean kingdom of Aram-Naharaim conventionally dated to 1150 BC. Even though the region was ruled in the earlier period by Indo-European/Hurrian princes, the indigenous population may have been Amorite. In this regard Goetze argues that:

Hurrian knights had then replaced the Amorite princes, taken over the best parts of the land for themselves and their liegemen (mariyannu), and now formed a caste of their own.[14].

If Goetze is right in his understanding of the change in political control of the Khabur region, then it would not be a giant leap of the imagination to suggest that, following the collapse of the Mitannian Dynasty during the 13th century, it was the native Amorite population, now described as Aramaeans by the Assyrians, which again rose to the forefront of the political scene and provided the new bulwark against early Assyrian expansion. This hypothesis transforms the historical picture from the standard view of a new group of Aramaean invaders arriving from the Syrian plains and western Arabian peninsula into something quite different. Instead, with the overthrow of the Indo-European/Hurrian ruling class which had previously dominated the territories to the west of the Assyrian heartland, we see a simple change in adversary for the rising power of Assyria in the form of the re-emerging old Amorite population, dominated in particular by one tribe – the 'Ahlamu Aramaeans'.

That the Sutu were also a force to be reckoned with in the 14th century is surely evident from their appearance in the Golden Horus name of Amenhotep III which is first attested in a stela from Aswan dated to Year 5 of the king. There Amenhotep is called hwi Sttyw 'smiter of the Sutu'.[15] This group were therefore clearly seen by the Egyptians as a major adversary at this time.

Egypt: The el-Amarna Letters

In the el-Amarna correspondence (1360-1335 BC) we come across for the first time in Egyptian sources the group of people called the 'Ahlamu' who apparently occupy parts of Syria. The letters were written in Akkadian, although the provenance was Egypt, and so this name occurs in its non-Egyptian form. These Ahlamu are referred to as 'brigands' [EA 200] and are associated with another group called the Sttyw (the Sutu already mentioned above) who have been holding up the messengers of Pharaoh returning from Mesopotamia [EA 195].

The term Ahlamu or 'hlmw contains the frequently used 'h' of the cuneiform texts, which in Egyptian vocalisation and writing may well have been dropped. The letter 'l' is, of course, interchangeable with 'r' and the 'w' ending represents the plural nominative termination. Thus it is possible to argue with confidence that the terms '(h)lm(w) and 'rm(w) or Aramu belong to the same basic stem and may indeed represent one and the same peoples. There is therefore the possibility of Aramaeans appearing on the scene as early as the end of the 18th Dynasty in Egypt (c. 1350 BC) at about the time that Mitannian control of the North Syria region was starting to wane.

It is universally accepted that Hadadezer, king of Aram Zobah and adversary of king David, was a 10th-century Aramaean ruler. However, in the el-Amarna correspondence of 1350 BC, the name Hadadezer appears in its abbreviated form of 'Aziru' (biblical -ezer), the king of Damascus. Thus an Aramaean king's name is employed by a 14th-century ruler whose territory coincides with the later Aram Zobah of the 10th century. The Hittite king Shuppiluliuma I, in his letters to Pharaoh, calls this same Aziru 'king of the Amorites'.

A more speculative but very interesting linguistic idea suggests that the Aramaeans were known to the Egyptians even as far back as the Middle Kingdom.[16] The so-called 'Execration Texts' of this period refer to a people called '3m. In these texts, the aleph glottal stop is used to represent the Semitic post-vocalic 'l' in the transcriptions of some Levantine place-names and their rulers.[17] It is therefore a possibility that '3m represents 'lm or 'rm and this could be seen as the Egyptian writing of Ahlamu or Aram, though some caution is necessary in view of the initial 'ayin. In spite of the latter, Smith and Smith did in fact assume this view by using the Anglisization 'Alamu for '3m in their translation of the Kamose texts of the late 17th Dynasty.[18] Their translation would put the Ahlamu back into the 16th century and by consequence to at least the 18th century through the '3m of the Execration Texts. This would tie in well with the mentions of Sutu in the Mari archive.

Hatti

Shuppiluliuma I, as already mentioned, was a contemporary of Amenhotep III c. 1350 BC. He also had a battle near Carchemish in which the Sutu were a part of the enemy confederacy ranged against the Hittite army.

Three generations later, the Ahlamu are again preventing messengers from reaching their destinations - this time the couriers are from Kadashman-Enlil of Babylon on their way to Hattusili III of Hatti (c. 1270 BC).

Assyria

The Ahlamu/Aramaeans occur unequivocally in Assyrian texts some 220 years after the el-Amarna Period, in Year 4 of Tiglath-pileser I (c. 1110 BC). In his annals for that year the king states that he 'conquered six of their cities at the foot of Mount Beshri'. The use of the word 'city' in association with the Ahlamu clearly suggests a settled population by this time.[19] Tiglath-pileser went on to record 28 campaigns against the Ahlamu during his 38-year reign.[20]

Aramaean tribes also appear settled in Babylonia by the reign of Tiglath-pileser III (c. 740 BC) and it is generally thought that they had gradually infiltrated from the west as part of the overall movements of peoples during the troubled times of the 12th to 10th centuries. Again this group is not perceived as indigenous to the region but as a migrating/invading population. Brinkman, however, acknowledges the weaknesses on which this assumption rests:

... evidence regarding this supposed migration is frustratingly sparse; and, in many instances, one may question whether the prevailing historical reconstructions are satisfactory.[21]

He further adds:

In surveying the evidence available on the Arameans who affected Babylonia between 1150 and 746, we find that we are not in a position to answer even such essential questions as: who were these Arameans and where did they come from, ...?[22]

Thus the Egyptian evidence, its corroboration from Hatti, and indeed that from Tiglath-pileser I's own records combines to cast considerable doubt on the hypothesis of an Aramaean invasion of northern Mesopotamia in the late-12th century BC. The Aramaean population appears to have been settled in northern Syria and probably the Khabur Triangle for at least 150 years prior to this time and most likely for a considerable time longer. This is further suggested by a reference to 'the mountains of the Ahlami' in a campaign text from the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I (c. 1235 BC). The Ahlamu/Aramaeans cannot therefore be regarded as forming a major part of the widespread population movements which are believed to have taken place at the end of the Late Bronze Age. Their political emergence probably took place around two centuries earlier during the LH IIIB period and may have originally been the rising of an indigenous 'serf' population which brought about the overthrow of their Indo-European/Hurrian overlords – the Mitannian Dynasty. Even if no direct evidence for this uprising is currently available, there is certainly sufficient circumstantial evidence to point to the Aramaean population filling the political vacuum following the sudden and mysterious disappearance of the Mitannian kingdom. Their raids into Assyrian territory may well have been caused by 'land-hunger' brought about by severe famines which, according to ancient sources, appear to have been widespread at this time.

Babylonia

In Lower Mesopotamia we find that a king of Babylon, Adad-apla-iddina (c. 1060 BC), was himself an Aramaean [23] and that the Neo-Babylonian dynasty of later years was of Aramaean stock. Simbar-Shipak (c. 1020 BC) of the Second Sealand Dynasty had to repair the cult centres of Sippar and Nippur following attacks of Sutu and Aramaeans some twenty years earlier [24] and another inscription mentions the throne of Enlil, made in the time of Nebuchadnezzar I (c. 1120 BC), which the Aramaeans had taken away from Babylon [25]. Later, Nabu-apla-iddina (c. 860 BC) defeated the Sutu and set about restoring the shrines that they had destroyed in these earlier times.[26]

Thus the Aramaeans were very active in southern Mesopotamia throughout this long period, during which time they spasmodically gained effective control of much of the region. This, however, does not in my view constitute evidence of population movements or invasions and could equally represent the fluctuating fortunes of an influential settled group living within the multi-racial population of the region. These tribes may have lived in the area for many centuries prior to their rise to power.

The Aramaic Language

Although not absolutely identifiable as the precursor to Aramaic, Amorite seems to have contained many elements that were later to form the basis of Aramaic grammar, including the method of indicating the plural and the verbal structure. The other major influences on early Aramaic were Phoenician and Ugaritic. Later it borrowed further from the Mesopotamian scripts before becoming the lingua franca of the Levant in the Persian period.[27]

Chronological chart showing a selection of Amorite/Aramaean 'events' from 2000 BC to 850 BC

DateBC

1950 Abraham 'the Aramaean wanderer' leaves Ur.

1850 Possible mention of Alamu in the Execration Texts of the Middle Kingdom in Egypt. The Sutu appear in the Mari texts as 'plunderers'.

1800 Naram-Sin fights against 'Harshamadki lord of Aram'.

1790 Rim-Sin of Larsa encounters Sutu.

1550 The Kamose texts mention Asiatics called '3mw/Alamu.

1381 Amenhotep III 'the smiter of the Sutu' marries a princess of Naharin.

1350 Ahlamu and Sutu appear in the el-Amarna Letters. Aziru of Amurru could be an Aramaean Hadadezer.

1270 More Ahlamu in the reign of Kadashman-Enlil.

--------------------

1150 SUPPOSED INVASION/MIGRATION OF THE ARAMAEANS INTO NORTHERN MESOPOTAMIA.

1110 First use of the term Aramaeans during the reign of Tiglath-pileser I – they are referred to as dwelling in cities.

1060 Adad-apla-idinna, an Aramaean, becomes king of Babylonia.

1020 Simbar-Shipak repairs shrines damaged by Aramaeans.

1000 David defeats Hadadezer of Aram-Zobah.

860 Nabu-apla-idinna defeats the Sutu.

Conclusion

As far as I have been able to ascertain, none of the inscriptions from the records of the ancient Near East suggest an invasion or major movement of population by the people known as the Aramaeans in around 1200 to 1100 BC. The sudden appearance in Assyrian documents of the name Ahlamu Aramaeans in the reign of Tiglath-pileser I may be explained by the paucity of annals surviving from the century immediately prior to his reign and the ineffectual rule of the Assyrian kings preceding this veteran campaigner.

The Assyrian attacks on the Khabur Triangle are not considered by scholars to be either invasions or population movements because it is tacitly understood that the Assyrians had dwelt in the region between the two Zabs for several centuries prior to their expansion in the 11th century. I see no reason to take a different view in respect of the Amorite/Aramaean peoples. I suggest that, in attacking Assyria, they were doing no more or no less than their neighbours, all of whom were trying to capitalise on the power vacuum created by the collapse of firstly the Mitannian kingdom and then later both the Hittite and Egyptian empires in northern Syria.

Although much of the above argument is based on the phonetic similarities between the names of various groups appearing in the ancient texts, I feel that there is sufficient other supportive evidence to show continuity of occupation in the region by both the Ahlamu and Sutu. Because the phonetic arguments are not therefore applied in isolation I believe there is justification for some speculation on the origins of the Aramaeans using this methodology.

Cook tells us that by the time of the Persian Empire:

Important peoples like the Hittites and Aramaeans, the Philistines, and the Edomites had more or less lost their identity, as the Midianites, Amorites and Amalekites had done earlier'.[28]

One might be entitled to question the assumption that the Amorites had ever really disappeared from the scene. Rather perhaps they had become known by the new name of Aramaeans, adopted from what was originally a smaller branch of the whole Amorite group. This new name was to become synonymous with the general population of the region for many centuries and the language which these people spoke became the lingua franca of the first millennium BC in the Levant.

It is interesting to note that the root 'Aram' may remain to this day in the name most commonly used to describe the people of the Near East – the modern 'rb/Aribi. The lip consonants 'm' and 'b' in Semitic languages have often become interchanged over the passage of time. It is thus likely that the modern word 'Arab' is a direct descendant of the ancient name 'rm/'lm although this must, of course, be considered in the light of a different historical perspective.

Notes and References

1. For the standard view of the widespread population movements and a detailed historical analysis of the dispersion of the Aramaean states c. 1200-700 BC see: J. D. Hawkins: 'The Neo-Hittite States in Syria and Anatolia' in Cambridge Ancient History Volume III, Part 1, (Cambridge University Press, 1982), pp. 372-441. For a map of the Neo-Hitite/Aramaean city states see p. 374.

2. W. F. Albright: 'Syria, the Philistines, and Phoenicia' in Cambridge Ancient History Volume II, Part 2A, (Cambridge University Press, 1975), p. 532.

3. Ibid., p. 533.

4. K. M. Kenyon: Amorites and Canaanites (Oxford University Press, London 1966), p. 3.

5. J. A. Brinkman: A Political History of Post-Kassite Babylonia (Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, Rome 1968), p. 267.

6. Ibid., p. 282.

7. A. T. Clay: The Empire of the Amorites (Yale University Press, Newhaven 1919), Chapter X.

8. Ibid., p. 67.

9. Ibid., p. 71.

10. J. A. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 285.

11. R. T. O'Callaghan: Aram Naharaim: A Contribution to the History of Upper Mesopotamia in the Second Millennium B.C. (Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, Rome 1948), p. 94.

12. J. A. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 274, note 1767.

13. In the Petrie Collection at UCL.

14. A. Goetze: Hethiter, Churriter und Assyrer (Oslo, 1936), p. 1.

15. W. Helk: Urkunden IV, 1663.

16. This idea was developed in discussion with Professor Smith who first brought my attention to the possibility during an Egyptian Language class last term.

17. G. Posener: Princes et Pays d'Asie et de Nubie (Bruxelles, 1940), pp. 41-2.

18. H. S. Smith and A. Smith: 'A Reconstruction of the Kamose Texts' in Zeitschrift fur Agyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, Vol. 103 (1976), p. 52.

19. A. K. Grayson: Assyrian Royal InscriptionsVolumes 1 & 2, (Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1976), pp. 13-14.

20. J. B. Pritchard: Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1969), p. 275.

21. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 268.

22. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 280.

23. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 279.

24. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 150.

25. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 152.

26. Brinkman: op. cit., p. 189.

27. Albright: op. cit., p. 530.

28. G. A. Cook: North Semitic Inscriptions, p. 175.

Published on September 27, 2012 12:25

September 13, 2012

Pillars of the New Chronology

The Fifteen New Chronology Pillars

Methodological Standpoint:

(A) The biblical text should not be rejected as an historical source without first testing the 'historical' contents against the archaeological record. However, the archaeological record needs to have a reliable and well-defined chronology which, at this time, we do not believe is the case.

(B) The later chronology of the Old Testament has proved to be substantially correct when tested against the external evidence of Assyria and Babylonia. Furthermore, a limited number of texts from Palestine confirm the historical background of the kings of Israel as portrayed in Kings and Chronicles – including the actual names of biblical kings and their officials. The question therefore is not whether the Old Testament is a reliable historical source but for how far back in time is it a reliable historical source?

(C) A reassessment of the chronological duration of the Egyptian TIP has brought us to the position where we feel that we can make a positive contribution to this important biblical question.

A Basic Outline of the New Chronology

1. The entry of the proto-Israelites into Egypt took place in the late 12th Dynasty.

2. More specifically, Joseph was a vizier under the co-regent pharaohs Senuseret III and Amenemhat III.

3. The absolute dates for these two kings are derived by chronological calculations based on the research of Dr David Lappin who has demonstrated that the most accurate date for Amenemhat III – based on the sequence of lunar month-lengths found in contracts of the period compared to lunar month durations calculated using astronomy computer programmes – is 1678-1634 BC. Likewise the dates for Senuseret III have been confirmed as 1698-1660 BC.

4. The Asiatic settlement of Avaris, founded in the reign of Amenemhat III (located at what is now the village of Tell ed-Daba in the eastern Delta), represents the settlement of Jacob and his sons. This extended family formed the original nucleus of the Asiatic population in Avaris.

5. The biblical tradition of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt is a memory of this Asiatic movement into the Eastern Delta during the late Middle Kingdom and early Second Intermediate Period – specifically the late 12th & 13th Dynasties.

6. Domestic slaves attested in documents of the period have typical Israelite names which in this New Chronology are in reality personalities from the Sojourn period, whereas in the Old Chronology they represent pre-Israelite Canaanites living in Egypt.

7. The Exodus of the Israelites took place towards the end of the 13th Dynasty which correlates with the abandonment of the Israelite quarter at Tell ed-Daba (Stratum G) and the contemporary death pits discovered at the site.

8. The tradition, reflected in the works of Artapanus, that Moses was raised by Pharaoh Khenofres is regarded by the New Chronology as fixing the lifetime of Moses to the era from Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV (Khenophres) to Dudimose (Tutimaeus).

9. Likewise, Manetho's Tutimaeus, identified here with Dudimose, becomes the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

10. The destruction of MB IIB Jericho is equated with the destruction of Jericho by Joshua and the Israelites.

11. Following the work of John Bimson, the destruction of numerous Canaanite cities in the MB IIB period represents the true archaeological setting for the military conquest and settlement of the Israelite tribes in Canaan.

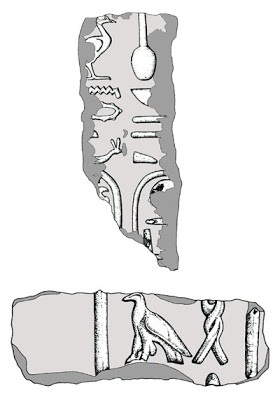

12. The evidence from a Karnak relief dating to the 19th Dynasty strongly suggest that the 'Israel' of the Merenptah Stela was capable of chariot warfare which in turn places the military conflict between Egypt and Israel in the United Monarchy Period or later. The Old Testament clearly establishes the first use of chariotry in the reigns of David and Solomon.

13. Shoshenk I is not Shishak because (a) from the internal Egyptian evidence (genealogies) he cannot be dated earlier than 850 BC and (b), through links to statue inscriptions from Byblos, he reigned only three generations (of 21 years each) before Tiglath-pileser III (745-727 BC), i.e. 63 years + c. 745 BC = c. 808 BC. Furthermore, (c) the Shoshenk I campaign inscription in no way compares to the biblical narratives dealing with the campaign of Shishak.

14. The earliest established date in Egyptian chronology is year 1 of Taharka = 690 BC. This is based on his 26th and last year being tied to 664 BC and the Assyrian sack of Thebes.

15. From 664 BC onwards the Orthodox and New Chronologies generally coincide.

Published on September 13, 2012 10:19

September 10, 2012

Book Review

REVIEW ARTICLE ON DAVID ROHL’S WORKFOR NEW LIFE MAGAZINE, MELBOURNE

by Anthony van der Elst (Chairman of the Institute for the Study of Interdisciplinary Sciences)

The Old Testament is pure myth. There were no Israelites in Egypt. Moses never existed. The Exodus never happened. Joshua and the Israelites did not conquer the Promised Land. There was no mighty warrior-king called David, and though Solomon might have been an impoverished tribal chieftain he was certainly no merchant prince with a high-born Egyptian wife. This was the view of modern scholarship at the beginning of the 1990s.

Little archaeological evidence was accepted as corroborating biblical stories, and for most of the last 200 years the academic trend had been to reduce the value of the Old Testament from historically useful narrative to worthless fiction. The most published, most translated, most famous writings were no better than Harry Potter and any scholar with the temerity to suggest that they were even a potential source of real history was derided as a crank. … But things were about to change.

In 1992 an assertive academic, Professor Thomas L. Thompson of Copenhagen University, published a book proclaiming the uselessness of the Bible to historical research, confidently denying the existence of such figures as David and Solomon. Within a few months, however, he learned that Professor Avraham Biran, excavating Tel Dan in northern Israel, had discovered fragments of a stela, probably dating to late 8th century BC, which referred to the 'House of David'. The myth was fighting back.

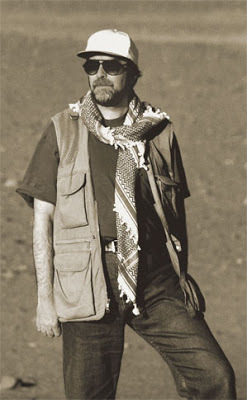

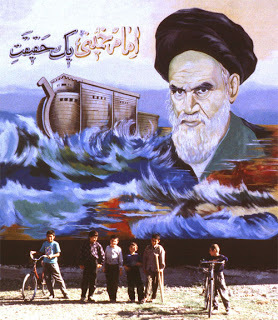

There had long been a sense of unease that something was rotten with the state of ancient Near Eastern history when, in 1995, a gifted and compelling voice demanded critical re-examination of the evidence. Crucial assumptions, handed on down through the years from professor to student, had received little such examination. Inconveniently obscure or confused periods tidied generations ago into ‘Dark Ages’ or ‘Intermediate Periods’ had become straight-jackets creaking with the double strain of unresolved contradictions and the insistent questions of modern scholarship. With his first book, A Test of Time, British Egyptologist David Rohl burst upon the scene and, in the words of the Sunday Times, 'set the academic world on its ear'.

Ancient Egypt – more specifically Egyptian chronology – is at the heart of the issue, for it is to Egypt that historians look to establish the principal timeline for Near East history. Addicted to record-keeping, Egypt also built higher and carved deeper than anyone else. Leaving the most impressive footprint in the sands of Time, it is Egypt that sets the reference points against which the chronologies of nearby peoples are correlated. If conventional Egyptian chronology rules out an event in the biblical lands, convention says it stays ruled out. But what if convention is wrong? Working in several different historical and scientific disciplines, Rohl and a number of colleagues are now developing an alternative chronology for the ancient world and, in the process, demonstrating that it is perfectly possible to fit much of the biblical story into a feasible archaeological framework.

Rohl is certainly not the first to question orthodoxy; flaws in conventional chronology have been exposed repeatedly. But the hour required the man … and Rohl was the man – organized, able, imaginative and tough; unafraid to challenge the sacred cows of Egyptology. A consummate communicator, Rohl writes and lectures brilliantly and is one of that rare breed of scholars who can talk to a lay public without condescension and with real passion. Reading Rohl, watching his television programmes or listening to his lectures, one is impressed by a wide-ranging mind completely at home in a familiar landscape. His obvious mastery of the subject, the clarity with which he lays bare the disturbing inconsistencies he is challenging, his impressive marshalling of facts and the lucidity of his arguments mark him out as an important voice in archaeology.

Because Rohl communicates better than anyone else in his field, he is generally regarded as the natural leader of the ‘New Chronology’ movement – although that movement is by no means as homogeneous or even as comradely as you might suppose! The New Chronology proposes that the conventional timeline of Ancient Egypt has become over-extended by perhaps as much as 350 years. This is not as extraordinary as you might imagine and influential scholars are indeed beginning to challenge the orthodox dating as it applies to biblical investigation. The leading Israeli archaeologist, Professor Israel Finkelstein, currently excavating Megiddo, is arguing for a revision of Solomonic archaeology by around 100 years, moving him from Iron Age IIA to the earlier Iron Age IB. But while Rohl would certainly approve the direction of the change, a mere 100 years lands the wealthy builder-king in the most impoverished part of the Iron Age without a major public building in sight! New Chronologists, going further than Finkelstein and adopting lower dates for Egypt’s New Kingdom, synchronize Solomon’s reign with the Late Bronze Age IIB when cities like Megiddo were at their cultural heights.

The collapse of ‘phantom’ years has fascinating and far-reaching consequences as the historical events and personalities that were sitting on top of them drop down in time to fill the space. To see how Rohl figures it out you will have to read A Test of Time. It has much to do with parallel dynasties, overlapping tombs, the removal of royal mummies to secret hiding places at dead of night, and the interpretation of some of the most striking and magnificent monumental inscriptions of the ancient world. Sometimes an explanation is as simple as early Egyptologists arbitrarily adding a few years to ‘fill a gap’; sometimes it seems that the historicity of the Bible rests on nothing more than a dispute over the number of mummified Apis bulls or the popular nickname of Ramesses the Great.

Rohl is not afraid to follow the logic of an argument. Again and again he points out startling synchronisms between attested events in Egyptian history and biblical (and extra-biblical) accounts – once that history has been redated using the New Chronology timeline. Readers will have to make their own judgments, but the number of matches is impressive. So striking, indeed, that the accusation has been made that it all works too suspiciously well. Rohl’s answer is to enquire mildly: ‘Why shouldn’t the truth work well?’

What truths might these be? Follow Rohl and you will be offered the reality of the origins of the early Israelites. Patriarch Joseph in his coat-of-many-colours is firmly placed in the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III and identified as the vizier who solved the problem of excessive Nile floods by channelling waters into the Faiyum Basin. Today that channel is still there and its traditional name is the Bahr Yussef(‘waterway of Joseph’). An elegant palace unearthed by Professor Manfred Bietak and his Austrian team in the Egyptian delta capital of Avaris is a strong candidate for the vizier’s home. Leaving aside the significance of the 12 pillars forming the entrance colonnade, the archaeologists found the remains of a large pyramid tomb, clearly that of an unusually important person, containing within it the violently defaced head and shoulders of a colossal statue of the missing occupant. Analysis of pigment traces show that the face was painted in the pale ochre traditionally used to indicate a Levantine ‘Asiatic’, and that the coat was geometrically striped in black, red, blue and white, again identifying the wearer as a tribal leader from the Semitic-speaking north. Bietak was surprised to find the tomb almost completely empty, with no body and no grave goods. Except for the vengeful attack on the statue, the tomb had been cleared rather than ransacked. Rohl reminds us that when the Israelite slaves won their freedom and departed from Raamses (Avaris) 'Moses took with him the bones of Joseph' [Exodus 13:19]. The statue was left behind, a mute target of Egyptian frustration then – an eloquent witness now.

Turning to the question of Moses, Rohl reminds us of the words of Roland de Vaux: ‘... it has to be acknowledged that, if Moses is suppressed, the religion and even the existence of Israel are impossible to explain’. A full and absorbing account of the evidence follows in which the Pharaohs of the Oppression and Exodus are identified and the city of the Israelite Bondage located and explored, including a reassessment of archaeological findings consistent (using New Chronology) with the disasters associated with the Tenth Plague tradition of the Exodus.

The Conquest, too, was always there, says Rohl, but scholars had not looked in the correct place on the historical timeline. The big problem was Jericho. When Kenyon conducted her famous excavation in the 1950s, she discovered a city whose fortified walls had indeed tumbled down and a destruction layer of impressive proportion buried in the Middle Bronze IIB stratum. The trouble was that convention set Joshua at the end of the Late Bronze Age, after the walled city had lain abandoned for centuries. With nothing to conquer, Joshua had to be myth too. But the New Chronology dates Joshua to the end of the Middle Bronze Age when the walls really did come tumblin’ down ...

Rohl argues cogently that the biblical Pharaoh Shishak, plunderer of Jerusalem, is wrongly identified in the conventional scheme. His candidate is Ramesses II. The reign of Akhenaten is reassigned too, making him contemporary with Saul and David and the Israelite Early Monarchy. Indeed, the very clay of the Bible Lands is made to speak as cuneiform tablets, the famous Amarna Letters found in Akhenaten’s Records Office, take on extraordinary significance, telling the story of an insubordinate vassal chieftain (Saul) loudly complaining of Habiru troublemakers in the hill-country south of Jerusalem (David and his Hebrews) before getting himself killed in circumstances consistent with the biblical account of the Battle of Gilboa. The argument is persuasive and the tablets telling the story can be gazed upon in the British Museum – unrecognized by the institution privileged to house them.

Rohl’s challenge has attracted a fair amount of criticism from the ‘establishment’ – perhaps unfair is the more proper adjective, for much of it has been grubby and unworthy of the academic positions his critics hold. Some objections betray an acceptance by the official mind of the grotesquely erroneous idea that imagination is hostile to science. The worst suggest that the New Chronology is viewed as a mortal threat to long-held academic and intellectual positions. Rohl is philosophical, reminding us that Sir Mortimer Wheeler described archaeology as a vendetta, not a science.

Having argued his hypothesis in A Test of Time and brought it to an international audience through the acclaimed TV series, Pharaohs & Kings, Rohl turned to the first book of the Old Testament and attempted to reconstruct it as history within his new chronological framework. Where A Test of Time (published as Pharaohs and Kings in the USA) focused specifically on the problems of Egyptian chronology and its impact on the historicity of the Old Testament, his next two books would show how a revised chronology might re-establish certain biblical texts as proper historical narratives based on actual events and real people.

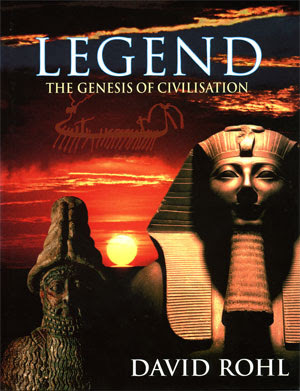

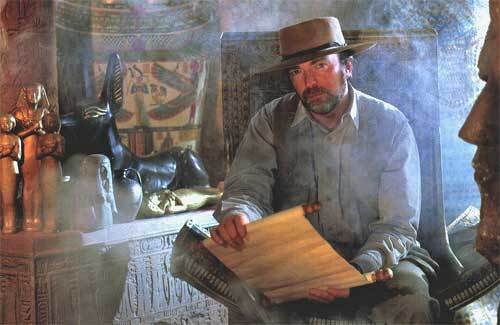

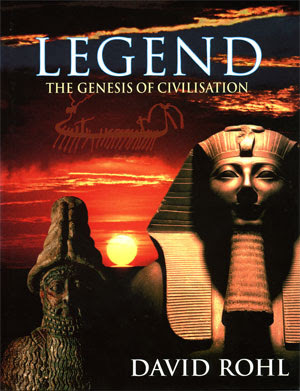

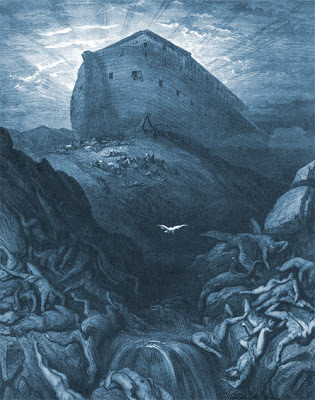

In Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation(1998), Rohl examines the sources of the book of Genesis together with corroborative textual and archaeological evidence from the beginnings of history in Mesopotamia. He tells the story of Adam’s people migrating out of the Zagros Mountains and eventually making their way to the swampy shores of the Persian Gulf. He charts the rise of the first civilization and finds confirmation of substantial elements of Genesis in the epic literature of ancient Sumer. Eden, Nod, Babel, the Deluge and Nimrod are all examined and found to have an historical basis, once stripped of mythic packaging.

In Legend, Rohl also advances an interesting hypothesis. Stemming directly from his own pioneering work in Egypt’s Eastern Desert, he discovers Mesopotamian origins for the pre-dynastic ancestors of the pyramid-builders. In 1908 Arthur Weigall, Inspector General of Antiquities in Luxor, found remarkable rock-carvings in the desert wadis east of Edfu. Among typical inscriptions were a multitude of prehistoric boat depictions. Strange boats. Boats with high prows; sea-going vessels, warlike and manned by many men. Some appeared to be dragged over the desert surface with long ropes, and figures of commanding stature bestrode the decks. The Great War intervening, it was not until 1936 that the German ethnographer Hans Winkler set out to discover more of this rock art, publishing his first report a year later. A second world war put paid to further expeditions when Winkler was killed on the Eastern Front weeks before the cessation of hostilities. Sixty years later David Rohl recognized the importance of these prehistoric images and set up the Eastern Desert Survey to search out the earlier discoveries and locate new sites. After directing and leading ten explorations, Rohl is now a world expert on these boat-pictures and believes them to be tangible evidence of a powerful Mesopotamian influx into Upper Egypt 5,000 years ago, their warships being literally dragged from the Red Sea to the Nile.

Rohl’s third book, The Lost Testament (2002), published in paperback (and in the USA) under the title From Eden to Exile, is a synthesis of all his previous work, drawing on the full range of sources, re-telling the epic story from a professional historian’s perspective and set against a real geographical and cultural background. The years of wandering in Sinai after the Exodus form an important section of The Lost Testament and it is worth remarking at this point that the accuracy and depth of the descriptive detail is often the result of intimate personal acquaintance with the terrain. For Rohl is not some cloistered academic pontificating from an institutional armchair; he has personally explored these places – often many times. He knows the colour of the desert at sunrise and the smell that rises from the hot stones of the Sinai mountains after a light rain; he has camped with the Bedouin and tasted the bitter waters of Marah; he has stood gazing at the head of cow-goddess Hathor carved from a rock on the heights of Serabit el-Khadim. Here he took the photograph that appears in The Lost Testament. Perhaps it was here, too, that he was struck by the significance of the golden calf made by the Hebrew slaves rescued by Joshua from the copper and turquoise mines of western Sinai.

Rohl has taken most of the photographs in his books. And what a fine photographer he is too. Why is this important? The eye is ‘the best witness’, said Dryden. Something you learn by direct seeing is called an observation; and observations always lie at the back of evidence. Rohl understands how to harness the power of visual imagery and the design of his books is distinguished by remarkable photography and first-class graphics.

Rohl is a fiendishly clever writer. He even manages the trick of occasionally letting his readers get ahead of him so that they work out a conclusion before he suggests it. No wonder his arguments are persuasive – you worked them out for yourself! As a detective story for intelligent, inquisitive people his seminal work, A Test of Time, is unmatched. If you know nothing of ancient history, fear not; it is the most agreeable rite-of-passage imaginable. Hundreds of thousands of readers have been gripped by it and will attest to having had a Eureka! moment when they realized that Egyptology was not only graspable, but actually made sense. This is a book that thinks. Of course it simplifies the subject for the layman and there are far too many issues and conundrums for even New Chronologists to agree upon, but it is so crammed with ideas and information and mystery and romance and excitement that I honestly believe that you will have the best time ever trying to find out. If I were the Egyptian Minister of Tourism, I’d send a copy to everyone on the planet.

Published on September 10, 2012 10:50

May 12, 2012

Filming in Luxor

Here are some pictures taken during the recent film shoot in Luxor. This feature film documentary on the Exodus will be released next year (2013) by the Mahoney Media Group throughout the United States before being re-edited as a television series for international broadcast.

Dawn at the chapel of Senuseret I in Karnak.

Dawn at the chapel of Senuseret I in Karnak.

Director Tim Mahoney lining up a shot in the temple of Medinet Habu.

Director Tim Mahoney lining up a shot in the temple of Medinet Habu.

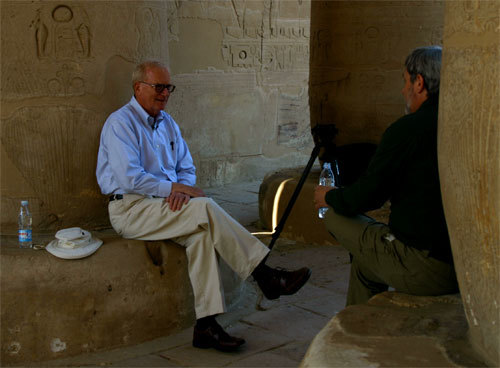

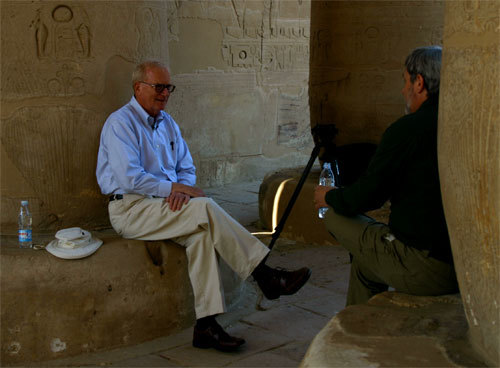

Interview with Professor Kent Weeks in the Ramesseum.

Interview with Professor Kent Weeks in the Ramesseum.

Examining the name 'Israel' on the Merenptah Stela (copy) in the king's mortuary temple on the west bank at Thebes.

Examining the name 'Israel' on the Merenptah Stela (copy) in the king's mortuary temple on the west bank at Thebes.

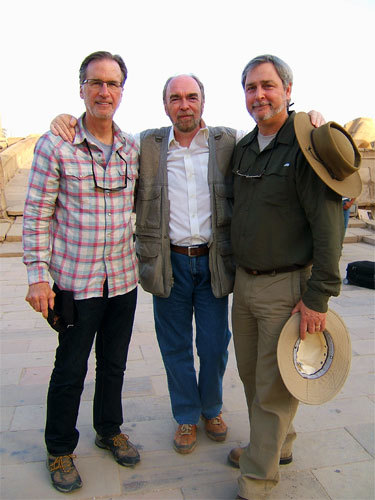

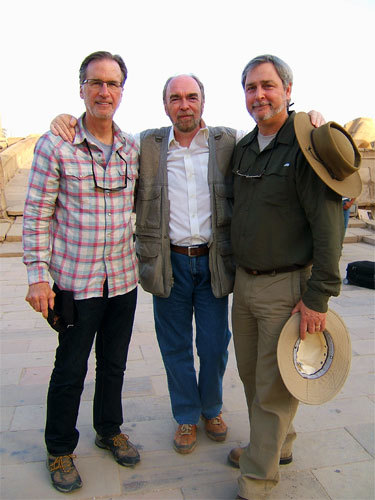

Kent Weeks, David Rohl and Tim Mahoney.

Kent Weeks, David Rohl and Tim Mahoney.

Walking the hypostyle hall at Karnak.

Walking the hypostyle hall at Karnak.

Akhenaten in the Luxor Museum.

Akhenaten in the Luxor Museum.

Director Tim Mahoney and David Rohl in discussion.

Director Tim Mahoney and David Rohl in discussion.

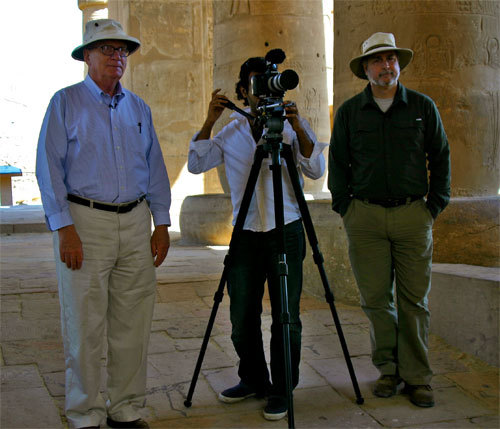

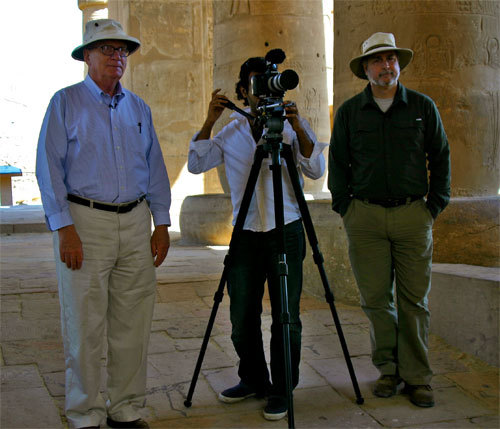

Executive Producer David Wessner, David Rohl and Director Tim Mahoney.

Executive Producer David Wessner, David Rohl and Director Tim Mahoney.

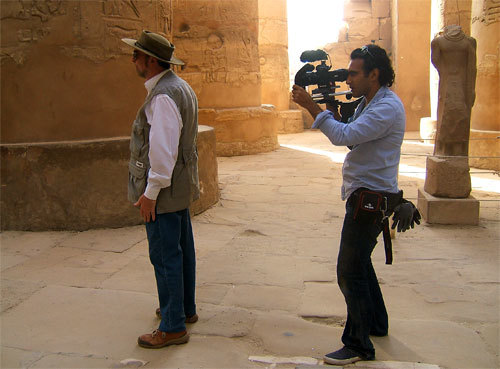

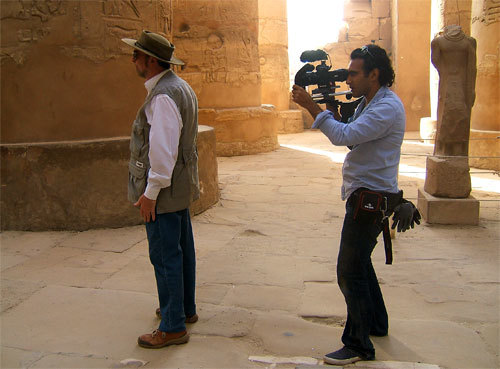

Cameraman Ramy Romany sets up a follow shot in the hypostyle hall at Karnak.

Cameraman Ramy Romany sets up a follow shot in the hypostyle hall at Karnak.

The feet of Ahmose II in Luxor Museum.

The feet of Ahmose II in Luxor Museum.

Filming the Sea Peoples reliefs at Medinet Habu.

Filming the Sea Peoples reliefs at Medinet Habu.

Chief Inspector Salah Elmasekh revealing Greek storage jars at his excavations in front of Karnak temple.

Chief Inspector Salah Elmasekh revealing Greek storage jars at his excavations in front of Karnak temple.

Tim Mahoney filming in Medinet Habu.

Tim Mahoney filming in Medinet Habu.

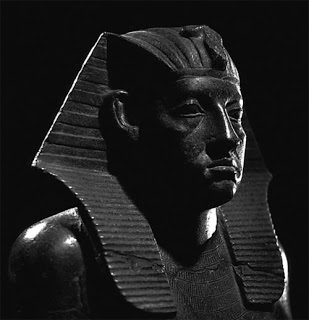

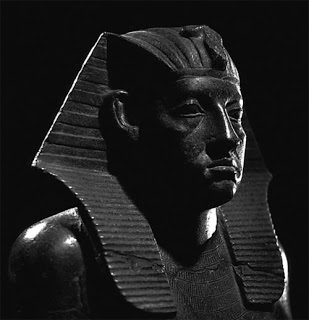

Senuseret III in the Luxor Museum.

Senuseret III in the Luxor Museum.

Production meeting in the recently excavated Greco-Roman baths at Karnak.

Production meeting in the recently excavated Greco-Roman baths at Karnak.

Filming at Medinet Habu beside the Sea Peoples reliefs.

Filming at Medinet Habu beside the Sea Peoples reliefs.

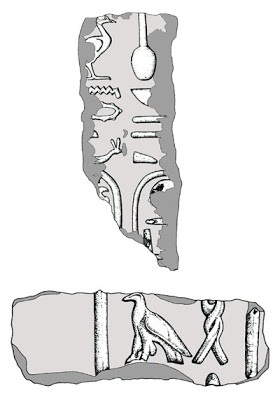

Examining the 'Israel blocks' at Karnak.

Examining the 'Israel blocks' at Karnak.

Mr Grumpy (Amenemhat III) in the Luxor Museum.

Mr Grumpy (Amenemhat III) in the Luxor Museum.

Waiting for action in the hypostyle hall at Karnak.