Elizabeth R. Ricker's Blog

January 25, 2022

Can Therapy and Neurohacking Work Together?

While I’ve always had a friendly stance toward therapy and medicine — my book has many strongly worded encouragements to would-be…

October 5, 2018

Can you do neuroscience research outside of the lab?

The brain is one of the most fascinating, complex, and deeply personal wonders of the world. Each of us carries one around each day, but very few of us get to see ours in action. But what if we could? We might discover truths not written in any textbook, yet.

Brain imaging equipment can cost millions of dollars and precise observational methods can require extensive training. This adds up to neuroscience researchers keeping all the brain-peeking fun to themselves, basically hanging out in labs discussing biological jewels that few others get to see. In fact, we enjoy hanging out there so much that even when we recruit people to participate in our research, we don’t even go to them. We require that they visit us in our labs. Then, we conduct the research behind closed doors, and if we’re lucky, the fruits of our work get published in academic journals, but locked behind paywalls. Wait, sorry, I got carried away, that’s a rant for another day. Back on topic.

Here’s my question: what if we could reverse this picture and go meet people where they are — by doing neuroscience research out in public?

On April 29, 2017, I began to do just that.

But really, why do it?One of the big problems in behavioral research — including psychology and neuroscience — is that 67–80% of what we know about the brain comes solely from college undergraduates (Henrich, 2010). Since there are fewer than 20 million undergraduates in the US out of a total population of around 325 million, that means we’re only studying about 6% of our population and hoping they generalize to the other 94%. Given how much we know that the brain changes from childhood to adulthood to older age, that seems pretty unlikely. Age is not the only difference, of course; the experiences we go through change our brains, so you are not even the same person you were yesterday. Anyway, before we go too far down that rabbit hole, I’ll just state my goal. Ultimately, I believe that we need to gather data from more people in research — explore all the beautiful neurodiversity that our species has to offer — in order to create personalized education, healthcare, and other systems. After all, we should create innovations that help all people, not just college students! Ok, soapbox speech ended. Now you understand my desire to leave the lab and venture out into the world in search of more representative data.

The March for Science in San Francisco agreed to take my organization (NeuroEducate) on as a partner, and I set up a booth there. With the help of wonderful research partners at Sapien Labs, as well as generous support from Muse, Muse Monitor, and a team of amazing volunteers, I went out into the crowds of San Francisco and showed people their brain activity in real time.

Huge thanks to the brilliant and kind Cheryl Isaacson at Lincoln Street Studios, the mastermind behind this short film.

Huge thanks to the brilliant and kind Cheryl Isaacson at Lincoln Street Studios, the mastermind behind this short film.After the March, a postdoc friend of mine at Stanford Medical School decided to join in on the next adventure. There was a music festival coming up that had expressed interest, and it seemed like a good event for us to set up our little mobile research shop. We had some questions, though…

Would gathering brain activity out in the open air at a music festival actually work?Our biggest worry was that the brain activity data would be too noisy to interpret. We used low-cost, consumer, mobile EEG headsets which are not as sensitive and accurate as in-lab rigs. Furthermore, concerts are loud. In addition to sound, there is electrical noise from the sound systems, what about muscle movement which has its own electrical signature, etc. Still, if it worked at all, and if we found enough non-college students interested in participating in our studies, we would be adding a valuable, underrepresented dataset. How? To offset the music, I used acoustic headsets — the type that construction workers use onsite — and had our participants wear them during the recordings. I used a few other tricks to improve the recordings, but even so, many of the signal quality issues had to be addressed during the data cleaning phase. If you have detailed questions about this, please reach out to the email at the bottom of this page and we’ll follow up with more detail.

What would people do while we recorded from them?Since there are so many unknowns when you leave the lab, I wanted to start by replicating a straightforward protocol used frequently in lab settings. If we got similar enough data out in the wild to what people get in the lab, we would have more confidence that we were getting “real” signal. Then, maybe we could push the envelope and ask questions not possible in a traditional lab setting. First things first, though: pick a nice, boring, simple protocol. Here’s what we chose: have participants sit quietly with their eyes open for 4–5 minutes and then with their eyes closed for 4–5 minutes and record their brain activity. Look for differences between the two conditions. If the differences look similar to what we see in the lab, use that as a baseline from which to do more exotic studies.

…Neuroscience out in the open?A few months later, we found ourselves at a Music and Science concert around 30 miles north of San Francisco, watching a laser light show, listening to a Pink Floyd tribute band, and enabling crowds of people to view their own brain activity in real time. Over the course of this second adventure (and the original one at the March for Science in San Francisco), a large, if somewhat unconventional, dataset began to form. We started to wonder whether we should share what we found.

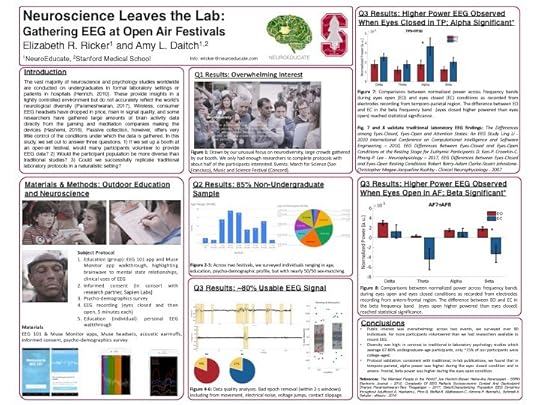

My collaborator and I put together a poster and submitted it to the International Mind, Brain, and Education Society. They were intrigued enough to accept it to their 2018 conference; this past weekend, we flew out to Los Angeles to present.

These were the three questions we asked in our research (and covered in our poster):

If we set up a booth at an open-air festival, would many participants volunteer to provide EEG data?Would the participant population be more diverse than traditional studies?Could we successfully replicate traditional laboratory protocols in a naturalistic setting? Also, could we get any kind of decent EEG data, given that we were outside, it was noisy, we had to convince people to sit still, etc?Spoiler alert: We were pleasantly surprised…Details in the poster below.

The big question…Could we capture usable amounts of brain activity data (using mobile EEG) from people sitting quietly, first with their eyes open and then with their eyes closed? Details above.

The big question…Could we capture usable amounts of brain activity data (using mobile EEG) from people sitting quietly, first with their eyes open and then with their eyes closed? Details above.If you’re interested in getting involved in conducting neuroscience outside of the lab (as a participant, a researcher, a sponsor, etc), or if you’re just wondering what other projects we’re up to, we’d love to hear from you! Just email info@neuroeducate.com.

Can you do neuroscience research outside of the lab? was originally published in NeuroEducate on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

October 1, 2018

Developing A Fitbit for the Soul: Learning From My Say to Do Scores Since 2011

The hell-hole I called my room

The hell-hole I called my roomThis is not a story about cleaning house, but it started out that way.

It was 2011, and my room was a cold mess. Describing it as a hot mess would have imbued it with more fun than the pathetic dumping ground was having.

Boxes. Shoes. Books. Papers. Piles and piles and piles. Repeat.

For years, I had been promising myself I would change my habits: put things away instead of dumping them on the floor and then dashing out the door, finally devoting a weekend to cleaning up. It fell off my to-do list over and over.

I’d been working on a three-person bootstrapped startup, had a long commute, and life was work and sleep and little else. I was just a couple years out of undergrad, and I wasn’t entirely sure what I wanted to do with my life, either. My room had started with a little mess, but soon the floor itself was no longer visible. Inviting people over to visit? No time. Decorations, personal touches? Barely memories. Finding your keys in under five minutes without digging through piles of clothing, papers, and books? The stuff of dreams.

After the startup finished, my “I-have-no-time” excuse evaporated. Now what? What to do next in life loomed large, but my room was such a mess it was physically blocking me from getting out the door each morning.

As I began to clean up the room, I was struck by all that had been taken for granted, improperly utilized, forgotten. It felt terrible. I realized the room was part of a lot of things I’d shoved aside for work; I had been breaking promises to myself for a while. But with every box sorted and trash bag that I threw out, something inside me got brighter, stronger, more determined.

This room was part of something bigger; I needed to reestablish trust with myself. There were so many things I wanted to do in life, but I had lost my own respect. I kept promises to others but not myself. You know those people with a quiet self-confidence, the ones who have gotten themselves out of tricky situations, done crazy hard things and come out victorious — but who are so good they don’t need to brag about it? How could I become like that? Basically, how could I gain my own trust and a well-earned self-respect? I reasoned that if I could keep promises to myself, I’d be even better at keeping promises to other people.

A plan began to form. Still fairly fresh from MIT undergrad, I gravitated toward a numerically driven system: I would track my own Say to Do score.

The Say part would be a system of promises: I would dream about the kind of life I wanted and then set a series of goals to accomplish that dream. The Do part would be a measure of how much I actually got done. If I did everything I said I would, my Say to Do score would be high. If I accomplished less, it would not.

With objective measures, with a way of actually tracking my Say to Do score, I could go beyond vague impressions and a bias toward generalizing from memorable events where I exceeded or failed my own expectations. We’ve got trackers for our steps, our heart rate, our finances…why not our personal integrity?

The question was how to do itMy professional work has been split between neuroscience research and developing software, so I Frankensteined together measurement methods from the lab and project management techniques from companies. Then, I mixed and salted to taste.

Initially, I called the system Scrum Life. It was in honor of the Scrum software project management system. I created burn up and burn down charts to track my own progress in the major projects in my life. From the neuroscience side, I used an operant conditioning treatment commonly used to train lab rats: rewards and punishments. Deciding what to do involved visualization techniques pulled liberally from the traditions of psychotherapy, and habit change techniques came from addiction research, behavioral economics research, and from “addictive product design” (software companies again).

My room improved.

Before on the left, after on the right. Yes, it’s the same room. Yes, it’s still not ready for Instagram.

Before on the left, after on the right. Yes, it’s the same room. Yes, it’s still not ready for Instagram.The room was just the start, though.

The systemIt would take many posts to explain the ins and outs of the system that I created. But, in short, it included the following: a buddy check-in system — an accountability buddy that met with me in-person and over the phone/Hangouts/Facetime. I supported my buddy, she supported me, we held each other accountable to the promises we made on a scheduled basis. That schedule was: annual, quarterly, weekly. We ran through what we had said we would do and what we had actually done, had our scores reviewed, received our consequences (rewards and punishments). Then, we said what we would do next. Scoring was a weighted score of the % of tasks I accomplished across Personal (40%) and Professional (60%). Sub categories within Personal included health, relationship/romance, friends/community, home/personal space, and spirituality. Sub categories within Professional included Cash (the % of revenue generating activities that I did such as earning money on an hourly or salary basis that I said I would do versus what I actually did) and Credit (the % of activities that I did related to professional development that I said I would do versus what I actually did) and Time spent (the % of hours I actually worked versus what I said I would).

To track my time and manage my concentration levels, I chunked my time into small time-chunks. Since I was working for myself during that time and wanted to maximize my productivity per hours worked, I tracked my hours using freelancer software.

To track it all, I tried out dozens and dozens of different systems. What I discovered was that there was real value in creating my own system from scratch using just Google Docs, Google Forms, Google Sheets, and Google Calendar.

Dreaming up my dream job, my dream relationship, my dream life…and getting them!…Then, realizing they were the wrong dreams… re-dreaming again, better…rinse, repeat…As I said, the room was just the start. At that point in my life, I needed a full overhaul: professionally and personally. Within a year of starting the system, I had gotten exactly the type of job, home, and relationship I had dreamed about. Did everything go perfectly and I lived happily ever after, The End? Of course not. Life is full of odd surprises and you don’t always know what you really want. Well, I don’t, anyway.

Want to see a video about this stuff? I gave a presentation at the Quantified Self conference a few years back. Check it out here: https://quantifiedself.com/show-and-tell/?project=1097

July 13, 2018

Five Mistakes Biohackers Make (and I’ve Definitely Made Them)

This guinea pig is learning how to run proper self-experiments

This guinea pig is learning how to run proper self-experimentsEver tried turning yourself into a human guinea pig?

Oddly enough, I have.

In attempts to improve my attention and memory, I have zapped my brain, altered my brainwaves, and even mailed my poop to a faraway lab. At other points, I tracked my time usage every five minutes using alarms and spreadsheets. I wrote down everything I ate. I went into a room full of strangers and laughed hysterically for an hour.

While this may sound bizarre, plenty of people are doing it. Some call themselves biohackers, others Quantified Selfers, others self-experimenters.

What if you were a human guinea pig already and you didn’t know it?

When we go into an ice cream shop and ask to try out multiple flavors, we compare the effects to see which one our taste buds like best. When we try out different workout regimens or diets in order to get in shape — and keep trying until we find the right one — we are taking baby steps toward human guinea pigging.

With a few tweaks, these could have become true self-experiments.

The goal of human guinea pigging is to learn about yourself as you are now, try things out on yourself, and see what helps make you a better or worse version of yourself. To make it a bit more powerful, you use measures that are as close to objective as possible. This keeps you honest and keeps you from conveniently mis-remembering things as better than they actually were (or, worse than they were, if you’re a pessimistic type).

The key is to avoid a few basic mistakes. These are five I’ve definitely screwed up before…

No (proper) baseline: Before grad school, I found out about a supplement that supposedly had cognitive enhancing abilities. Curious, I decided to try it out. At home, I couldn’t find the cognitive tests I usually used. So, I tried a different set of cognitive tests to measure my cognitive performance before and after trying the supplement. My performance went up…so, the supplements worked, right! Wrong. What was the problem? Practice effects. With most cognitive tests, you need to take the tests a few times before your performance plateaus. What I should have done was take the cognitive test a few times first and then take the supplements. Only then could I know whether my improvement was due to the supplements or whether it was just due to practice effects.Too many variables: During college, I gained around 30 pounds without noticing it (thank you baggy sweatshirts, Boston winters, and a breathtaking lack of self-awareness). At some point, I took a look at myself in the mirror, had a mild panic, and immediately began doing about a dozen things differently in order to get my old body back. The good news was that I recaptured my former weight, but the bad news is that I have no idea which of the many things I did (sleeping more, cutting out energy drinks, not eating after 7 pm, drinking only water, weight lifting, etc) made the biggest difference.Incomplete sample size: My mother told me about a guy she met in her early 20’s who she thought was ridiculously good looking. The first time she met him, she could barely think because she was so insanely, outrageously attracted to him. She saw him a few more times, finally listened to him when he spoke, and when the raging hormones subsided, she realized they had almost nothing in common. What if she’d only taken that first sample (their first meeting)? She might have mistakenly thought he was her one true love. Which would have been the stuff of a great rom-com but a terrible life story.Inaccurate measurements: Ever tried to measure your weight on a scale that varied your weight by a few pounds each time, even though you took the measures back to back? Unless your scale was also teleporting you onto other planets where you weigh different amounts (in that case, maybe let Elon Musk know you’ve found a much cheaper way to get to Mars), that’s a sign to throw that scale away.Poor record-keeping: People with handwriting as awful as mine should never be allowed to keep a journal. When I was a competitive athlete in high school, I used to write down my workouts and drills, as well as my thoughts and feelings before and after matches. A few years later, I came upon one of these old journals. Expecting a treasure trove of insight, I went to the kitchen and started boiling some water for tea — I was going to sit down and really cherish these detailed notes. I flipped open the first page. And discovered that I could read — maybe — half of it. Tried another page: same deal. Kept paging through. Soon, I realized that even if I could read it, what would I do with it? With little ability to search or digitize it, I knew I’d never actually use this information. Result: Sadness. Deep. Sadness. Ever since, I’ve relied on apps on my smartphone for workout tracking and journaling.There you have it. Five mistakes biohackers make — and as you just discovered, I’ve definitely made them. But now, you don’t have to. You’re welcome.

If you’d like to read more about neuroscience, self-experimentation, or related topics, sign up for more updates below.

https://medium.com/media/f8b2d05e950032440d68edd077d15038/hrefPhoto credit: by Otsphoto

Five Mistakes Biohackers Make (and I’ve Definitely Made Them) was originally published in NeuroEducate on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Five mistakes biohackers make (and I’ve definitely made them)

Guinea pig learning how to do proper self-experiments

Guinea pig learning how to do proper self-experimentsEver tried turning yourself into a human guinea pig?

Oddly enough, I have.

In attempts to improve my attention and memory, I have zapped my brain, altered my brainwaves, and even mailed my poop to a faraway lab. At other points, I tracked my time usage every five minutes using alarms and spreadsheets. I wrote down everything I ate. I went into a room full of strangers and laughed hysterically for an hour.

While this may sound bizarre, plenty of people are doing it. Some call themselves biohackers, others Quantified Selfers, others self-experimenters.

What if you were a human guinea pig already and you didn’t know it?

When we go into an ice cream shop and ask to try out multiple flavors, we compare the effects to see which one our taste buds like best. When we try out different workout regimens or diets in order to get in shape — and keep trying until we find the right one — we are taking baby steps toward human guinea pigging.

With a few tweaks, these could have become true self-experiments.

The goal of human guinea pigging is to learn about yourself as you are now, try things out on yourself, and see what helps make you a better or worse version of yourself. To make it a bit more powerful, you use measures that are as close to objective as possible. This keeps you honest and keeps you from conveniently mis-remembering things as better than they actually were (or, worse than they were, if you’re a pessimistic type).

The key is to avoid a few basic mistakes. These are five I’ve definitely screwed up before…

No (proper) baseline: Before grad school, I found out about a supplement that supposedly had cognitive enhancing abilities. Curious, I decided to try it out. At home, I couldn’t find the cognitive tests I usually used. So, I tried a different set of cognitive tests to measure my cognitive performance before and after trying the supplement. My performance went up…so, the supplements worked, right! Wrong. What was the problem? Practice effects. With most cognitive tests, you need to take the tests a few times before your performance plateaus. What I should have done was take the cognitive test a few times first and then take the supplements. Only then could I know whether my improvement was due to the supplements or whether it was just due to practice effects.Too many variables: During college, I gained around 30 pounds without noticing it (thank you baggy sweatshirts, Boston winters, and a breathtaking lack of self-awareness). At some point, I took a look at myself in the mirror, had a mild panic, and immediately began doing about a dozen things differently in order to get my old body back. The good news was that I recaptured my former weight, but the bad news is that I have no idea which of the many things I did (sleeping more, cutting out energy drinks, not eating after 7 pm, drinking only water, weight lifting, etc) made the biggest difference.Incomplete sample size: My mother told me about a guy she met in her early 20’s who she thought was ridiculously good looking. The first time she met him, she could barely think because she was so insanely, outrageously attracted to him. She saw him a few more times, finally listened to him when he spoke, and when the raging hormones subsided, she realized they had almost nothing in common. What if she’d only taken that first sample (their first meeting)? She might have mistakenly thought he was her one true love. Which would have been the stuff of a great rom-com but a terrible life story.Inaccurate measurements: Ever tried to measure your weight on a scale that varied your weight by a few pounds each time, even though you took the measures back to back? Unless your scale was also teleporting you onto other planets where you weigh different amounts (in that case, maybe let Elon Musk know you’ve found a much cheaper way to get to Mars), that’s a sign to throw that scale away.Poor record-keeping: People with handwriting as awful as mine should never be allowed to keep a journal. When I was a competitive athlete in high school, I used to write down my workouts and drills, as well as my thoughts and feelings before and after matches. A few years later, I came upon one of these old journals. Expecting a treasure trove of insight, I went to the kitchen and started boiling some water for tea — I was going to sit down and really cherish these detailed notes. I flipped open the first page. And discovered that I could read — maybe — half of it. Tried another page: same deal. Kept paging through. Soon, I realized that even if I could read it, what would I do with it? With little ability to search or digitize it, I knew I’d never actually use this information. Result: Sadness. Deep. Sadness. Ever since, I’ve relied on apps on my smartphone for workout tracking and journaling.There you have it. Five mistakes biohackers make — and as you just discovered, I’ve definitely made them. But now, you don’t have to. You’re welcome.

If you’d like to read more about neuroscience, self-experimentation, or related topics, sign up for more updates below.

https://medium.com/media/f8b2d05e950032440d68edd077d15038/hrefPhoto credit: by Otsphoto

Five mistakes biohackers make (and I’ve definitely made them) was originally published in NeuroEducate on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

May 29, 2018

Debugging Brains on the Drive from Stanford to San Francisco

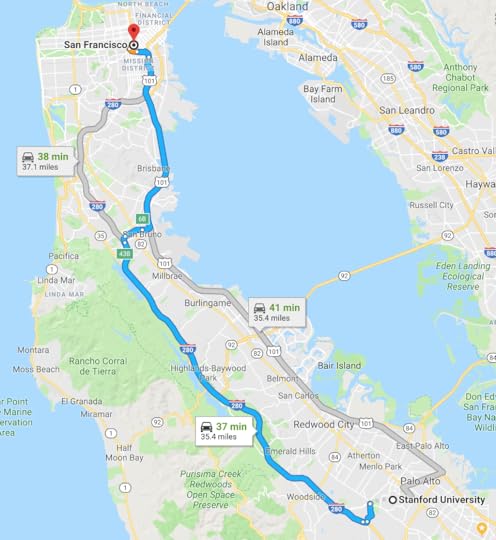

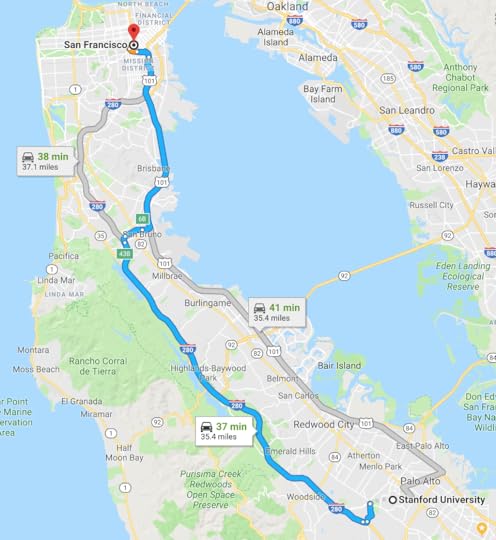

On a recent carpool back from a consulting project at Stanford, Adrian*, a 22 year-old scientist asked me how he might optimize his mental performance. He seemed genuinely curious, so I decided to answer in detail. We lived near each other in the city, so there was plenty of time remaining before either of us had to get dropped off.

“So, you study mental performance. Can you improve mine?” He asked. I looked at him calmly, and, with a straight face, told him: “No.”

He frowned at me. I remained straight faced. Finally, I laughed. “I’m kidding! I’m not saying I can’t help, I’m just saying I can’t do it for you.” He looked relieved. “Ok, so, you’re just saying, you want me to do work, too. You’re doing a ‘teach a man to fish so he can eat for a lifetime, don’t sell him a fish because he’ll just eat for one meal’ kind of thing?”

“Exactly,” I grinned back.

“Ok, ok,” He looked mollified. I rubbed my hands together.

“What’s your biggest annoyance when it comes to your brain?” I asked him. Adrian swallowed and looked away. “Attention. I’ve had difficulty focusing ever since I was a kid. I was even brought in and tested for ADHD. I tested positive for having it, but no one believed it because I was pretty high-achieving and people thought I was pretty smart.” He swallowed again, looked away with embarrassment, and then looked back with an expression that was part determination, part self-loathing, and a healthy heaping of curiosity.

Now, it was my turn to nod. I felt for him, regretting my earlier flippancy. “Adrian, just because you are high-achieving does not mean you are not struggling with attention. There are many, many reasons why a person can struggle with attention. They don’t necessarily have to do directly with cognition. Anxiety can masquerade as an attention problem, for instance. To figure out where your attention issues show up, you need to start investigating yourself like you would a subject in the lab. This time, the subject is you. Specifically, you’ll need personal data in four areas.”

As sun-kissed fields passed us on either side, a fog bank loomed in the highway just ahead — a signal that we were leaving the sunny South Bay and approaching San Francisco.

“Ok,” Adrian crossed his fingers. “What are the four areas?”

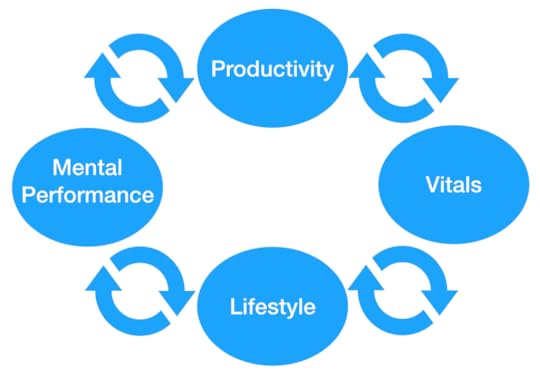

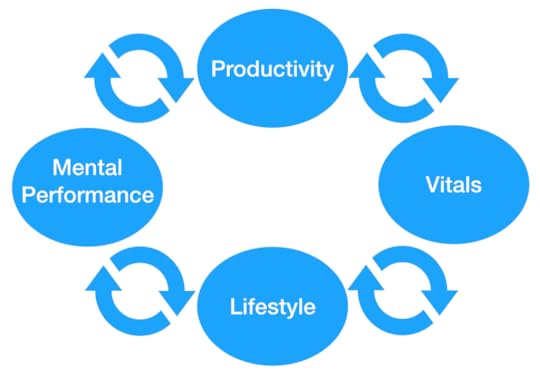

I began counting on my fingers. “You’ll want to get baselines in mental performance. In productivity — since that’s the output of your mental performance. In your vitals — because that feeds into both mental performance and productivity. Fourth, in your lifestyle habits.

As we drove through the fog, I explained the value of gathering personal data. I had been surprised many, many times after gathering real data on myself. The size of the gap between what I thought was going on and what was actually happening had been downright shocking at times. Sometimes, I was far more productive than I expected, my mind was performing better, my vitals reflected exceptional health, my lifestyle habits were not that bad after all. Other times, it was sobering: the hard data showed me just how far my improvement efforts would need to go.

Four areas feeding into (and out of) mental performance

Four areas feeding into (and out of) mental performance“Sounds good, but how do you actually measure?” He asked.

I raised my fingers again and began enumerating each of the four areas:

Mental Performance: you can measure your mental performance indirectly using brain game-like cognitive tests as well as with specific biological tests. One of my favorites is Quantified Mind, created by a Google AI researcher and a former Harvard psychology professor.Productivity: what you get done while you work, how many hours you work. You’ll need to use apps for this or special spreadsheets I can show you. The one I use most often is called Firepomo (disclosure: my husband wrote it and I consulted on its design). For time tracking, I’ve also used Harvest and Toggl.Lifestyle: you’ll need to measure your sleep, exercise, and diet and track how those affect and are affected by your mental performance and productivity. I created my own Google Forms and put a link in a daily Google Calendar event to remind me to fill them out.Vitals: pulse, respiration, temperature, blood components, saliva, poop, sleep debt…these are all terrific. They both affect and are affected by your mental performance and productivity. One of my favorites is using heart rate variability, ideally through a reliable and high precision device like the Apple Watch.Adrian commented, “Interesting that you don’t even need a neuroscience lab to measure those things.”

I smiled. “Yup, no neuroscience lab required. I’ve tried out dozens and dozens of tools, and now I focus exclusively on tools I can access at home because you can capture more data with higher frequency that way. Even the FDA is acknowledging the value of Real World Data these days. Sometimes, my friends and I make custom tools from scratch, but that’s not strictly necessary.” Adrian looked like he was about to ask a question — about those homemade custom tools or about recommended self-experiments — but we were running out of time. We were entering the city, and my house was first on the drop-off list.

Curious about the next step in this brain hacking adventure — or maybe, your own? Fill out the form below…

https://medium.com/media/173f6933a2a78002be77c6eec959f172/href*Notes: “Adrian” is not his real name.

Photo credit: Google Maps

Debugging Brains on the Drive from Stanford to San Francisco was originally published in NeuroEducate on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Brain-Hacking on the Drive from Stanford to San Francisco

If you had 15 minutes to improve your brain each morning, what would you do?

I’ve been in pursuit of this question for somewhere between half a decade and my entire lifetime. This mild obsession has taken me through neuroscience research at MIT and Harvard, tech startups, and ultimately, it turned me into a human guinea pig.

On a recent carpool back from Stanford, Adrian*, a 22 year-old scientist asked me how he might optimize his mental performance. He seemed genuinely curious, so I decided to answer in detail. We lived near each other in the city, so there was plenty of time remaining before either of us had to get dropped off.

“Honestly, I couldn’t really tell you how to improve your mental performance.” Adrian looked confused and a little disappointed. Hadn’t I just said I studied this stuff? “What I can tell you is how you can figure it out on your own. How you could optimize your own mental performance.” He nodded. “More of a teach a man to fish approach, rather than just giving him a fish.”

“Ok,” I rubbed my hands together. “What’s your biggest annoyance when it comes to your brain?” Adrian swallowed. “Attention. I’ve had difficulty focusing ever since I was a kid. I was even brought in and tested for ADHD. I tested positive for having it, but no one believed it because I was pretty high-achieving.” He swallowed again, looked away with embarrassment, and then looked back with an expression that was equal parts determination and curiosity.

It was my turn to nod now. “Just because you are high-achieving does not mean that you are not struggling with attention. There are many, many reasons why you might be struggling with attention, and they don’t even necessarily have to do directly with cognition. Anxiety can masquerade as an attention problem, for instance. To figure out where your attention issues show up, you need to start investigating yourself like you would a subject in the lab. This time, the subject is you. Specifically, you’ll need personal data in four areas.”

As sun-kissed fields passed us on either side, a fog bank loomed in the highway just ahead — a signal that we were leaving the sunny South Bay and approaching San Francisco.

“Ok,” Adrian crossed his fingers. “What are the four areas?”

I began counting on my fingers. “You’ll want to get baselines in mental performance. In productivity — since that’s the output of your mental performance. In your vitals — because that feeds into both mental performance and productivity. Fourth, in your lifestyle habits.

As we drove through the fog, I explained the value of gathering personal data. I admitted to him that I had been surprised many, many times after gathering real data on myself. The size of the gap between what I thought I was going on and what was actually happening was downright shocking at times. Sometimes, it was a pleasant surprise: I was more productive than I expected, my mind was performing better, my vitals reflected exceptional health, my lifestyle habits were not that bad after all. Other times, it was discouraging, but having hard data showed me how and where to focus my improvement efforts.

Four areas feeding into (and out of) mental performance

Four areas feeding into (and out of) mental performance“Sounds good, but how do you actually measure them?” He asked.

I raised my hand again and began enumerating each of the four areas:

Mental Performance: you can measure your mental performance indirectly using brain game-like cognitive tests as well as with specific biological tests. One of my favorites is Quantified Mind, created by a Google AI researcher and a former Harvard psychology professor.Productivity: what you get done while you work, how many hours you work. You’ll need to use apps for this or special spreadsheets I can show you. Two of my favorites are often used by freelancers but they can be used by self-trackers, too: Harvest and Toggl.Lifestyle: you’ll need to measure your sleep, exercise, and diet and track how those affect and are affected by your mental performance and productivity. I created my own Google Forms and put a link in a daily Google Calendar event to remind me to fill them out.Vitals: pulse, respiration, temperature, blood components, saliva, poop…these are all terrific. They both affect and are affected by your mental performance and productivity. One of my favorite new finds is using the smartphone camera to capture your heart rate variability (HRV) and interpret it using Welltory.Adrian commented, “Interesting that you don’t even need a neuroscience lab to measure those things.”

I smiled. “Yup, no neuroscience lab required. I’ve tried out dozens and dozens of tools, and now I focus exclusively on tools I can access at home because you can capture much more data and much more frequently that way. Even the FDA is acknowledging the value of Real World Data these days. Sometimes, my friends and I make custom tools from scratch, but that’s not strictly necessary.” Adrian looked like he was about to ask a question — about those homemade custom tools or about recommended self-experiments — but we were running out of time. We were entering the city, and my house was first on the drop-off list.

Curious about the next step in this brain hacking adventure — or maybe, your own? Fill out the form below…

https://medium.com/media/173f6933a2a78002be77c6eec959f172/hrefNotes: I received no financial kickbacks for any of the links above. Unrelatedly, “Adrian” is a pseudonym.

Photo credit: Google Maps

Brain-Hacking on the Drive from Stanford to San Francisco was originally published in NeuroEducate on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Brain-hacking on the drive from Stanford to San Francisco

If you had 15 minutes to improve your brain each morning, what would you do?

I’ve been in pursuit of this question for somewhere between half a decade and my entire lifetime. This mild obsession has taken me through neuroscience research at MIT and Harvard, tech startups, and ultimately, it turned me into a human guinea pig.

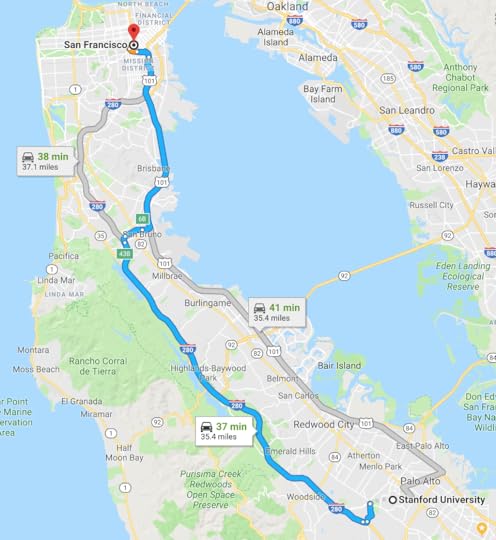

On a recent carpool back from Stanford, Adrian*, a 22 year-old scientist asked me how he might optimize his mental performance. He seemed genuinely curious, so I decided to answer in detail. We lived near each other in the city, so there was plenty of time remaining before either of us had to get dropped off.

“Honestly, I couldn’t really tell you how to improve your mental performance.” Adrian looked confused and a little disappointed. Hadn’t I just said I studied this stuff? “What I can tell you is how you can figure it out on your own. How you could optimize your own mental performance.” He nodded. “More of a teach a man to fish approach, rather than just giving him a fish.”

“Ok,” I rubbed my hands together. “What’s your biggest annoyance when it comes to your brain?” Adrian swallowed. “Attention. I’ve had difficulty focusing ever since I was a kid. I was even brought in and tested for ADHD. I tested positive for having it, but no one believed it because I was pretty high-achieving.” He swallowed again, looked away with embarrassment, and then looked back with an expression that was equal parts determination and curiosity.

It was my turn to nod now. “Just because you are high-achieving does not mean that you are not struggling with attention. There are many, many reasons why you might be struggling with attention, and they don’t even necessarily have to do directly with cognition. Anxiety can masquerade as an attention problem, for instance. To figure out where your attention issues show up, you need to start investigating yourself like you would a subject in the lab. This time, the subject is you. Specifically, you’ll need personal data in four areas.”

As sun-kissed fields passed us on either side, a fog bank loomed in the highway just ahead — a signal that we were leaving the sunny South Bay and approaching San Francisco.

“Ok,” Adrian crossed his fingers. “What are the four areas?”

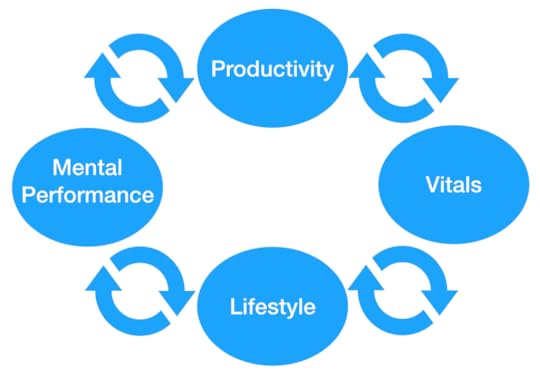

I began counting on my fingers. “You’ll want to get baselines in mental performance. In productivity — since that’s the output of your mental performance. In your vitals — because that feeds into both mental performance and productivity. Fourth, in your lifestyle habits.

As we drove through the fog, I explained the value of gathering personal data. I admitted to him that I had been surprised many, many times after gathering real data on myself. The size of the gap between what I thought I was going on and what was actually happening was downright shocking at times. Sometimes, it was a pleasant surprise: I was more productive than I expected, my mind was performing better, my vitals reflected exceptional health, my lifestyle habits were not that bad after all. Other times, it was discouraging, but having hard data showed me how and where to focus my improvement efforts.

Four areas feeding into (and out of) mental performance

Four areas feeding into (and out of) mental performance“Sounds good, but how do you actually measure them?” He asked.

I raised my hand again and began enumerating each of the four areas:

Mental Performance: you can measure your mental performance indirectly using brain game-like cognitive tests as well as with specific biological tests. One of my favorites is Quantified Mind, created by a Google AI researcher and a former Harvard psychology professor.Productivity: what you get done while you work, how many hours you work. You’ll need to use apps for this or special spreadsheets I can show you. Two of my favorites are often used by freelancers but they can be used by self-trackers, too: Harvest and Toggl.Lifestyle: you’ll need to measure your sleep, exercise, and diet and track how those affect and are affected by your mental performance and productivity. I created my own Google Forms and put a link in a daily Google Calendar event to remind me to fill them out.Vitals: pulse, respiration, temperature, blood components, saliva, poop…these are all terrific. They both affect and are affected by your mental performance and productivity. One of my favorite new finds is using the smartphone camera to capture your heart rate variability (HRV) and interpret it using Welltory.Adrian commented, “Interesting that you don’t even need a neuroscience lab to measure those things.”

I smiled. “Yup, no neuroscience lab required. I’ve tried out dozens and dozens of tools, and now I focus exclusively on tools I can access at home because you can capture much more data and much more frequently that way. Even the FDA is acknowledging the value of Real World Data these days. Sometimes, my friends and I make custom tools from scratch, but that’s not strictly necessary.” Adrian looked like he was about to ask a question — about those homemade custom tools or about recommended self-experiments — but we were running out of time. We were entering the city, and my house was first on the drop-off list.

Curious about the next step in this brain hacking adventure — or maybe, your own? Fill out the form below…

https://medium.com/media/173f6933a2a78002be77c6eec959f172/hrefNotes: I received no financial kickbacks for any of the links above. Unrelatedly, “Adrian” is a pseudonym.

Photo credit: Google Maps

Brain-hacking on the drive from Stanford to San Francisco was originally published in NeuroEducate on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.