Sarah Albee's Blog, page 18

September 11, 2014

Tough to Swallow

A few days ago my writer friend, Erin Dionne, posted this status update:

Erin is a fantastic writer, incidentally. You should read her new book, if you haven’t yet.

Erin is a fantastic writer, incidentally. You should read her new book, if you haven’t yet.

She followed up with

(Loree Burns is another writer friend, who has written several nonfiction books about insects. If you don’t yet have them, you should run out and buy all of her books immediately.)

(Loree Burns is another writer friend, who has written several nonfiction books about insects. If you don’t yet have them, you should run out and buy all of her books immediately.)

Erin’s post sparked a lively conversation in the comments, where many of Erin’s friends began to speculate about just how long a live insect, swallowed whole, might survive inside her stomach. The fiction writers were nice—“the stomach acid would kill it right away.” Those of us who write nonfiction weren’t so sure. How long could a fly survive in an anaerobic environment full of hydrochloric acid? I surmised it would stay alive “thirty minutes, tops.” Loree, who joined the conversation a bit later, recommended that Erin read Hugh Raffles’ Insectopedia for an overview of aeroplankton. “He describes the stuff we breathe as ‘a vault of insect-laden air from which falls a continuous rain.’ Of bugs. We’re all breathing them in more than we think.” Kind of like krill for land animals. For some reason, Erin didn’t seem to take comfort in our comments.

And luckily for Erin, I happened to be reading Mary Roach’s Gulp, and had just reached a section (chapter 9, pp 167 – 177) where she discusses this very topic: could a nonparasitic creature swallowed whole survive inside a stomach for any length of time? For instance, if your pet reptile swallowed a live mealworm, could that mealworm chew its way out of your pet reptile’s stomach (as has been rumored on various internet listserves)?

In fact, mealworms actually can live awhile inside the reptile’s stomach, although they go dormant once they’ve been swallowed. Still, they don’t get digested quickly. Turns out, hydrochloric (gastric) acid isn’t nearly as caustic as you might think. Roach quotes a herpetologist who reported watching a crab-eating snake (Fordonia leucobalia) vomit up crabs three hours after eating them, and the crabs stood up and ran away. Another scientist tells the story of his dog, Gracie, a part-Doberman, who vomited up a two foot garter snake in the middle of the floor during a dinner party. Gracie had been inside the house for at least two hours. When his wife picked up the snake with a wad of paper towels, it flicked its little tongue out at her. (160) (I cited this latter story to Erin in a follow up comment. Judging by the responses, some of the fiction writers didn’t seem to have the proper takeaway.)

Update: I just emailed Erin to ask if she minded being featured in a blog post about swallowing live living things, and she said no, but that in fact, she hadn’t actually swallowed her bug. “It flew into my mouth, *stuck to my uvula* and I horked it back out,” she reported. Well, now we’ll know in case the worst happens next time.

By Siga [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Tough to Swallow appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 8, 2014

Poisonous Powders

Livre d’heures de Jean de Montauban – Bibliothèque des Champs Libres

One of my favorite memories from childhood was opening a new box of crayons. I marveled at the beautiful hues. When I was older and took painting classes, I never lost that feeling of awe at the brilliant, saturated colors that came right out of the paint tube. But five hundred years ago, painters didn’t have the luxury of buying their paints from the art supply store. They had to mix their own colors. This was often difficult, expensive, or dangerous. Sometimes it was difficult, expensive and dangerous. What’s amazing is how they still managed to produce such intense, gorgeous colors.

First, to get the terms straight: the pigment is the coloring agent in paints. It usually came in powdered form and, pre 19th century, was almost always found in nature (animal-based, plant-based, or from naturally occurring minerals). Painters mixed the powdery pigment with a binding agent so that it could be applied as paint. Binding agents could be any number of things, but they included egg tempera, pine resin, gum arabic, honey, and even earwax.

Here are how some common colors from medieval and Renaissance times were produced. If you didn’t already appreciate beautiful paintings from these periods, you’ll surely do so now, just for the sheer energy it took to produce the colors. (It wasn’t always the artist himself who made the pigments, of course. It might have been his assistant, or someone else at the monastery.)

Reds

Many of the so-called “red lakes” were made from ground up insects. To produce them, painters boiled up the powdered, dried lac, kermes, or cochineal insects with urine or lye, and then mixed it with a binding agent.

Vermillion, another red color, was made from cinnabar, which is the principal ore of mercury. Or you could just heat together sulphur and mercury to form an artificial cinnabar. (Heating up mercury? Never a good plan.) Traces of cinnabar have been found in the bones of medieval scribes, and probably hastened them toward an early death.

Masters of the Dark Eyes Missal, Initial S with Presentation in the Temple, Walters Manuscript W.175, fol. 158v

Blues

Azurite was a deep blue pigment that contained arsenic sulphide, and creating it produced a toxic gas called mercury cyanide. It was expensive, but slightly cheaper than ultramarine, the most expensive pigment. Ultramarine was made by grinding up the precious stone lapis lazuli, and because it was so expensive it was reserved mostly for paintings of Christ and the Virgin.

The Wilton Diptych By Unknown Master, French (second half of 14th century) (Web Gallery of Art: via Wikimedia Commons

Gold was often used to gild manuscripts. The painter started with a base adherent and then carefully positioned the gold leaf on the page. After it dried, the excess was removed.

Aussem Hours, SS. Catherine and Barbara, with gold and floral marginal decoration, Walters Manuscript W.437, fol. 108v

Lamp black was made from soot or charcoal.

White lead pigment was made by suspending strips of lead over vinegar or urine inside a vase. The vase was sealed, and buried in a dung heap for a few days. A crust formed on the lead. It was scraped away and ground up.

Albrecht Durer, detail, Four Holy Men

Green pigments included verdegreen, malachite, and Spanish green. Many of these were derived from arsenical compounds and were highly toxic.

Albrecht Durer, Portrait of Maximilian I, 1519

Yellows

Orpiment, also called King’s Yellow, was made from a volcanic stone with a sparkly quality that was found all over the world. It was extremely poisonous, as it, too, contained arsenic.

Sources:

https://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~cochinea/pdfs/a-baker-04-pigments.pdf

http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/i...

http://www.jcsparks.com/painted/pigment-chem.html

http://web.princeton.edu/sites/ehs/ar...

The post Poisonous Powders appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 4, 2014

Greetings to All

As I may or may not have mentioned in my last blog post, one of the best–but also most perilous–things about doing research is that it’s so easy to get sidetracked. While looking for images for my book proposal, I spent a lot of time that I don’t really have to spare looking at Victorian/early twentieth century greeting cards on various archives (British Museum, Library of Congress, and New York Public Library). They’re fascinating.

As I may or may not have mentioned in my last blog post, one of the best–but also most perilous–things about doing research is that it’s so easy to get sidetracked. While looking for images for my book proposal, I spent a lot of time that I don’t really have to spare looking at Victorian/early twentieth century greeting cards on various archives (British Museum, Library of Congress, and New York Public Library). They’re fascinating.

The penny post was introduced in Britain in 1840, and that meant a lot of people could afford to send mail. According to the British Museum website, in 1843 an art shop owner printed a thousand greeting cards and sold them in his shop in London for a shilling apiece. The railroads encouraged sending greeting cards—Christmas and Valentines were especially popular–and posting them got even cheaper in 1870.

Have a look at some of these. I didn’t see many cute puppies and kittens like the ones you see on greeting cards nowadays, I guess the creepy dogs in the two cards, below, might have been meant to be cute:

But naked cherubs tended to be popular.

But naked cherubs tended to be popular.

And weird social commentaries with anthropomorphized animals.

And cars bedecked with flowers but no drivers seemed like popular settings in the era when the first cars rolled out: I’m not sure what this one is supposed to be about–the caption says “Happy may your Christmas be,” but to me it looks more like the boy with the whip is menacing the cowering boy in blue. And he’s definitely smooshing the kid’s hat:

I’m not sure what this one is supposed to be about–the caption says “Happy may your Christmas be,” but to me it looks more like the boy with the whip is menacing the cowering boy in blue. And he’s definitely smooshing the kid’s hat:

If you click on the picture it will take you to the British Library url and you can see it enlarged.

Now I really have to get back to my research.

The post Greetings to All appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 1, 2014

Research Diversions

By Roger from Derby, UK Preserved Chemists shop in Derby Silk Mill via Wikimedia

I have a new favorite publication. During my recent week of research in New York City, I spent many happy hours poring over nineteenth century copies of The British Medical Journal. I found it so diverting—literally—that it was difficult to stay focused on my area of research. It’s written in a very approachable, conversational style, well, for a medical journal—with lots of first-hand accounts from doctors about their ailing patients. And you find yourself filling in the human details between the lines.

For instance, in the correspondence section of the July 12, 1862 issue, there’s a lively dialogue between those in favor of sending people home with poisons in bottles marked with a “difference in shape and mode of pouring” and those who think it’s a dumb idea. Why sure, the first camp argues, it’s better to package the poison in a specially shaped bottle, so that when Mother sends seven-year-old Suzy to the corner store to collect a half pound of sugar for the trifle and a half pound of arsenic to kill the rats, Suzy will have a fighting chance not to get the two identical substances confused as she carries the packages home all jumbled up in her little white apron. The other camp thinks it’s the person’s own fault if he doesn’t bother to look carefully. As one Mr. Squire at the Pharmaceutical Society put it, “Such a person deserves to be poisoned.”

Then there’s the article entitled “Loss of an Eye from the Bite of a Leech” (May 31, 1862), where a doctor named Mr. Von Graefe (they weren’t called “Dr.” then) recounts that his patient, a five year old child, “had on account of headache been ordered a leech to the right temple.” The leech ended up crawling over to her eye, resulting in, well, just imagine. “Where were the parents?” I almost shouted. Why did no one realize the stupid leech had crawled to her eye? They don’t move that quickly! And why is Mr./Dr. Von Graefe publishing this story of his own ridiculous incompetence? These were the heady days before malpractice.

I could keep going and going. In the 6/14/1879 issue, a doctor describes how a guy purchased a doll for his one-year-old. The baby put the doll in her mouth and fell gravely ill. Turns out, the doll had a long green dress that was loaded with arsenic.

I’ll end with an article not from the BMJ but from my second-favorite publication, The Lancet (4/27/1861). A Mr. Skey recounts three patients of his, girls aged 15, 16, and 17, whom he treated for “enlarged bursae over the knee.” Touchingly, he dubs this malady “Housemaid’s Knee,” because it was “brought on by kneeling on a hard floor or stone steps whilst following their occupation as servants.” I think Mr. Skey might have been secretly hoping his name for this affliction might gain rapid popularity and perhaps accord him, in turn, some name recognition, but I don’t think the name stuck.

Julien Dupré La Vache Blanche

The post Research Diversions appeared first on Sarah Albee.

August 28, 2014

Top Ten Viking Nicknames

The subject of today’s hilarity will be nicknames from the Viking Age. (I did a post awhile back about some of my favorite royal nicknames.) As with most people living in medieval times, the Norse had no last names (surnames), outside of patronyms (Ander’s son, Peter’s son). So, as happened frequently in other medieval communities, nicknames were used as a way of identifying individuals. We’ve all heard of Eric the Red, but there are lots of better ones. The list below comes from the people who settled in Iceland during the 9th and 10th centuries. Some are too randy to list on this PG-rated blog. Most are not very flattering. Here are my top ten favorites:

The subject of today’s hilarity will be nicknames from the Viking Age. (I did a post awhile back about some of my favorite royal nicknames.) As with most people living in medieval times, the Norse had no last names (surnames), outside of patronyms (Ander’s son, Peter’s son). So, as happened frequently in other medieval communities, nicknames were used as a way of identifying individuals. We’ve all heard of Eric the Red, but there are lots of better ones. The list below comes from the people who settled in Iceland during the 9th and 10th centuries. Some are too randy to list on this PG-rated blog. Most are not very flattering. Here are my top ten favorites:

Audun Thin-Hair

Gunnstein Berserks’-Killer

Herjolf Bent-Arse

Audun Thorolfsson the Rotten

Eystein Foul-Fart

Asbjorn Muscle of Orrastead

Thorir the Troll-Burster

Thurid the Sound-Filler (I’m guessing she was a loquacious woman.)

Thorbjorg Ship-Breast

Ljot the Unwashed

Sources: http://www.medievalists.net/2014/06/01/viking-nicknames/

The Book of Settlements: Landnámabók by Hermann Pálsson http://books.google.com/books?id=jj6c...

The post appeared first on Sarah Albee.

August 25, 2014

Analyze This

I’m working on a new book right now, and as part of my research, I have enrolled in an online course on forensics. My professor is one Roderick Bates, an organic chemist and associate professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. I find him delightful. Soft-spoken, with a pleasant British accent, he wears a white lab coat and safety glasses, and he delivers his lectures about heinous crimes involving wood chippers, analysis of body tissues found in chain saws, and body-dissolving sulphuric acid in bathtubs, with a charming exuberance and a hint of a smile playing on his lips.

Professor Bates

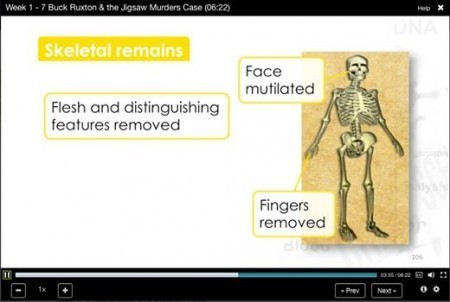

In the first week we got an overview of what we’re going to be studying in more depth—stuff like forensic entomology, facial reconstruction, voice recognition, and DNA analysis. Things were pretty simple in Week 1. We saw slides like this:

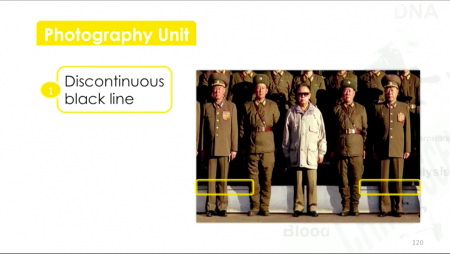

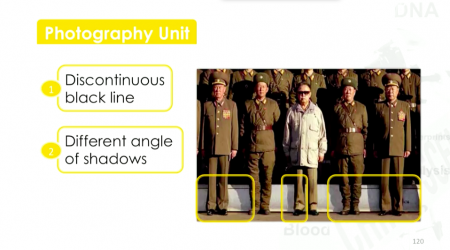

Even though I’m primarily enrolled to learn more about toxicology, I’m finding so much else so fascinating. For instance, Professor Bates showed us this photo of the late North Korean leader, Kim Jong-il. He hadn’t been seen in public for some time, so to quell growing suspicion that Kim Jong-il might be, er, ill, the North Koreans issued this photograph.

Even though I’m primarily enrolled to learn more about toxicology, I’m finding so much else so fascinating. For instance, Professor Bates showed us this photo of the late North Korean leader, Kim Jong-il. He hadn’t been seen in public for some time, so to quell growing suspicion that Kim Jong-il might be, er, ill, the North Koreans issued this photograph. Professor Bates showed us why it’s easy to see the photo has been doctored. If you look closely at the black line running along the white platform behind their legs, you can see that it is not continuous, and the shadows aren’t falling the same way for the Dear Leader as they do for the others in the photo:

Professor Bates showed us why it’s easy to see the photo has been doctored. If you look closely at the black line running along the white platform behind their legs, you can see that it is not continuous, and the shadows aren’t falling the same way for the Dear Leader as they do for the others in the photo:

Plus, he explained, a close examination of the pixilation confirmed that the image of Kim didn’t match up.

Plus, he explained, a close examination of the pixilation confirmed that the image of Kim didn’t match up.

I just completed Week 2, and things have started to get a little more complicated. Now we’re seeing slides like these:

But complicated or not, Professor Bates has remained charming and engaging, and I’m kind of able to follow the chemistry and molecular analysis discussions. I can hardly wait until we get to the toxicology unit!

But complicated or not, Professor Bates has remained charming and engaging, and I’m kind of able to follow the chemistry and molecular analysis discussions. I can hardly wait until we get to the toxicology unit!

The post Analyze This appeared first on Sarah Albee.

August 18, 2014

My Geek Week

This week, Dear Reader, I won’t be posting, as I’m doing research for my next book. I’m staying in the empty apartment of a New York City friend and will be spending all my time here, at the New York Academy of Medicine:

And here, at the New York Public Library.  Back next week!

Back next week!

The post My Geek Week appeared first on Sarah Albee.

August 14, 2014

Fashion Fail

Last month when I was in Paris my husband and I spotted a statue in a small park, and long before we were close enough to read the inscription I said, “That is so the 1830s.” Here’s the statue. In case you can’t see the inscription, the date is 1830.

Not that I should get mad props for ID-ing the fashion era. The period from 1830 to the early 1840s was marked by a very characteristic look in fashionable European and American circles. I loathe it.

Not that I should get mad props for ID-ing the fashion era. The period from 1830 to the early 1840s was marked by a very characteristic look in fashionable European and American circles. I loathe it.

1835

Besides being extreme in its silhouette, I find everything about the look so . . . depressing. Everything drooped. Hairdos were curled and plastered to the forehead or else looped in front, like the ears of a morose basset hound. Sleeves slid off the shoulders and then ballooned out into absurd proportions. Tight, fitted bodices set off huge skirts, which were draped and flounced and beribboned. Have a look at some of these and see if you don’t agree with me:

1835

Kids suffered, too. Gone were the relatively comfy skeleton suits worn by boys of the past decades (see my blog here). Back came the corsets and tight collars and heavy fabrics:

Kids suffered, too. Gone were the relatively comfy skeleton suits worn by boys of the past decades (see my blog here). Back came the corsets and tight collars and heavy fabrics: But it was the little girls who really had it bad. The muslin and cotton dresses that had been so popular in previous decades gave way to heavy brocades and velvets with tightly-laced bodices and multiple petticoats padding out their heavy, uncomfortable skirts. For early Victorians, it wasn’t just fashionable to upholster your sitting room–you had to upholster your kid as well. Have a look:

But it was the little girls who really had it bad. The muslin and cotton dresses that had been so popular in previous decades gave way to heavy brocades and velvets with tightly-laced bodices and multiple petticoats padding out their heavy, uncomfortable skirts. For early Victorians, it wasn’t just fashionable to upholster your sitting room–you had to upholster your kid as well. Have a look:

The post Fashion Fail appeared first on Sarah Albee.

August 11, 2014

Swarmed

Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Roman Dictator

Bibi Saint-Pol, own work

The first time I stumbled across a reference to the disease known as phthiriasis (pronounced “thuh-RY-uh-sis) I was reading Plutarch’s gleeful account of the death of the Roman tyrant Sulla.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138 – 78 BC), who had a nasty habit of putting his enemies’ heads on pikes, died a relatively old man, having murdered all the people who might try to assassinate him. And yet, according to Plutarch, Sulla met a ghastly end.

Sulla became sick with an intestinal hemorrhage. Said Plutarch, “the corrupted flesh broke out into lice. Many men were employed day and night in destroying them, but they so multiplied that not only his clothes, baths, and basins, but his very food was polluted with them.”

According to this article by J. Bondeson MD, PhD, in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Sulla may or may not have had phthiriasis. If he did, the bugs swarming out of his guts were not lice but mites, which can infest a person with an already-weakened immune system. As Sulla was so roundly hated by most Romans, Plutarch may have simply wished he’d had the disease. That seems to have been a pattern: most ancient writers agreed that phthiriasis was a disease contracted as a punishment by the gods, divine retribution for tyrants and various enemies of prevailing religions.

J. Bondeson tells us that phthiriasis has a long history. Aristotle wrote about it. Galen did, too. So did Pliny the Elder, but he wasn’t much of a detail-oriented guy and was wrong about, well, pretty much everything. Still, there are lots of accounts of this gruesome flesh-eating disease from ancient times.

In Acts of the Apostles, after Herod Agrippa was hailed as a God, “an angel of the Lord smote him because he did not give God the glory, and he was eaten by worms and died.’

Doubt has been cast about whether this disease actually existed, but Bondeson cites several reliable cases of phthiriasis dating from the 16th century, and regular mention of it in textbooks and case reports well into the nineteenth century. In case after case, the victims fell ill with many swellings all over the body that eventually burst, and from which small insects streamed out. Nice. Linnaeus called it “louse fever,” and recommended slathering the patient with mercurial ointment.

Did the disease really exist? Bondeson and others believe so. He cites various entomologists who think the mites may have been a species similar to one that infests birds.

It remains a mystery as to why the disease vanished so suddenly by the 1870s. Some medical historians speculate that that species of mite may have gone extinct. Whatever happened to them, I’m glad they’re gone.

The post Swarmed appeared first on Sarah Albee.

August 7, 2014

Renaissance Road Trips

Chenonceau Castle

On a recent trip to France, we passed by many châteaux in the Loire valley, each more magnificent than the next. The Loire valley is not very close to Paris—it’s about 110 miles from Paris to Chateau de Chambord, for instance—and I wondered how long it took sixteenth century travelers to make this journey—and why there were so many castles.First, the distance. Under the best of conditions (good roads, decent weather, level ground), humans can walk four miles per hour over long distances. Horses can’t do much better–maybe five mph—but a lot less if they’re pulling something or if roads are in awful condition. A horse can canter at 20 mph, but it can only do that for six to eight miles at a time, after which it will slow down and walk, or stop completely. So it would have taken a long time to get from place to place. Under the best conditions, a journey from Paris to Chambord would have taken three weeks. But in fact, it took a lot longer than that. Because in the sixteenth century, the royal court didn’t just hop on a horse and head to their country home. They took everything and everyone with them, loading all the stuff onto the backs of horses and mules.

Catherine de Medici traveled with her ladies and gentlemen, foreign ambassadors, dwarves, pet bears, servants, retainers, attendants, apothecaries, astrologists, tutors, musicians, cooking pots, food, clothing, portable triumphal arches, wall hangings, and furniture.

And second: the reason there were so many castles is simply that the court in Renaissance times –thousands of people–had to move around from estate to estate so as to find new hunting grounds. Once they’d exhausted the food supply in the area, they moved on to the next estate. Also, the sanitation was dreadful. After thousands of people had taken up residence in and around a great estate for a few weeks, filth piled up, and with it, stench and disease.

And second: the reason there were so many castles is simply that the court in Renaissance times –thousands of people–had to move around from estate to estate so as to find new hunting grounds. Once they’d exhausted the food supply in the area, they moved on to the next estate. Also, the sanitation was dreadful. After thousands of people had taken up residence in and around a great estate for a few weeks, filth piled up, and with it, stench and disease.

The royal procession could be miles long. According to Leonie Frieda’s Catherine de Medici, the beginning of the royal caravan sometimes entered a town before those traveling at the back of it had left the last one.

The post Renaissance Road Trips appeared first on Sarah Albee.