Sarah Albee's Blog, page 17

October 20, 2014

What’s My Line?

By Richwales (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

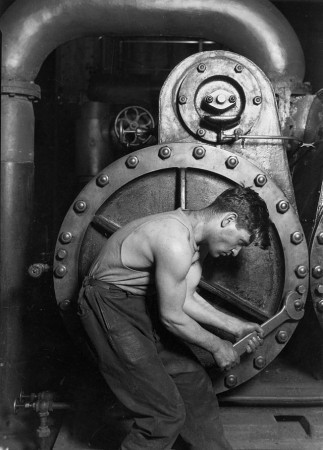

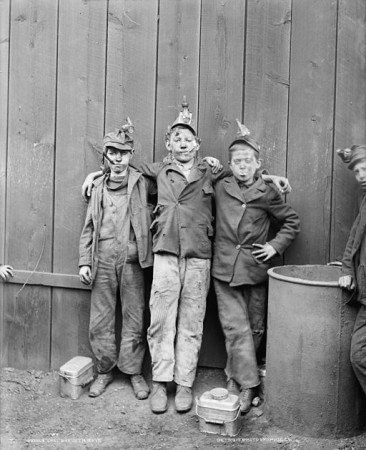

When I was in New York last week, walking along Third Avenue, I noticed two twenty-something women in front of me. It was immediately evident what they did for a living. As I passed them I turned and said, “You’re both ballerinas, right? You walk in second position.” They both laughed and nodded.Nowadays you don’t generally know what someone does for a living based on how she walks or dresses, unless it’s a firefighter in uniform, or a police officer, or perhaps a doctor in scrubs. But in times past, for the 97% of people who made up the “laboring classes,” everyone knew what you did based either upon the clothes you wore or the afflictions from which you suffered—or both.

Mechanic (Lewis Hine, Lib of Congress)

Jack London’s 1903 book The People of the Abyss is a first-hand account of what life was like in the working class slum known as the East End, in London. He bought the clothes of an unemployed American sailor at a second-hand clothing shop. He then spent several months living in workhouses, slums, and hop picking. It’s a fascinating (albeit wrenching) book.

Jack London, in his second-hand clothing

In his book Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain, Anthony S. Wohl discusses a number of “industrial diseases” as having been accepted as an inevitable part of working life. Miners had asthma. Matchmakers had phossy jaw. Lead workers had palsy. You recognized the tailors by their concave chests and stooped shoulders, the potters by their paralyzed wrists, the copper workers by the greenish tint of their hair, teeth, and skin, and the hatters by their unsteady gait and trembling hands. (264-5)

Breaker boys

Hop pickers, 1944

It’s a different time, now, of course, and mass-production of clothing makes it much more difficult to tell who does what for a living. Still, whenever I’m in a big city, I enjoy trying to guess.

Anthony S. Wohl, Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983. All images except top one LOC.

The post What’s My Line? appeared first on Sarah Albee.

October 13, 2014

WNPR This Thursday!

On Thursday, I’m going to be on the Colin McEnroe show, with WNPR, based out of Hartford. The subject of the show is Poop. It airs from 1 to 2 pm EST.

On Thursday, I’m going to be on the Colin McEnroe show, with WNPR, based out of Hartford. The subject of the show is Poop. It airs from 1 to 2 pm EST.

My fellow panelists are Rose George, author of the amazing book The Big Necessity, (among others), and MIT Professor Eric Alm.

You can stream it live here. http://stream.wnpr.org

You can stream it live here. http://stream.wnpr.org

The post WNPR This Thursday! appeared first on Sarah Albee.

October 9, 2014

Death By Apple

I stumbled across a strange, sad little anecdote the other day as I was researching something on another topic. It was a picture of a little girl in a fashionable dress, and the author casually mentioned that the child died a few days after the picture was taken. The cause of her death was a stomach ache after eating green apples.

That struck me as so odd. I did a quick search. I was astonished—a search of death from green apples in the historic newspapers database from 1790 to the present database yielded 800 stories.

Here are just a few:

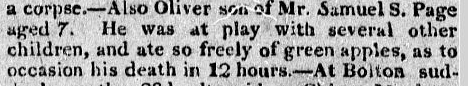

From 1817:

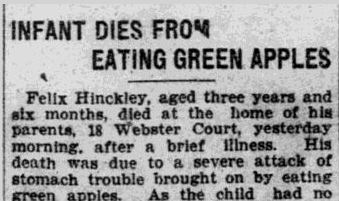

and 1901 and 1911:

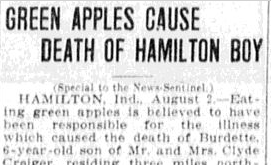

and 1911:

and 1921

They go on and on, but by the late 1920s you stop seeing death notices due to green apples. Doctors quoted about the causes of death from green apple ingestion range from acute indigestion to convulsions to cholera. Articles from the 1930s to the 1970s include lots of advice columns that warn people to avoid green apples. By the 1980s, all the articles are recipes that include green apples.

They go on and on, but by the late 1920s you stop seeing death notices due to green apples. Doctors quoted about the causes of death from green apple ingestion range from acute indigestion to convulsions to cholera. Articles from the 1930s to the 1970s include lots of advice columns that warn people to avoid green apples. By the 1980s, all the articles are recipes that include green apples.

The latest reference I could find suggesting they’re toxic is from a veterinarian in the Cleveland Plain Dealer (12/20/1961), who says green apples are bad for horses–and for children–because they ferment in the large intestine, causing the abdomen to swell and leading to severe pain and convulsions.

I wonder if the apples really did kill the kids, or if it might have been something else. It could have been cholera I suppose, which is a waterborne illness but can be transferred by flies to improperly washed vegetables. Or they might have ingested too many apple seeds, which contain cyanide and really can kill you in large doses.

I am working on researching the cause. If you have theories/leads, please let me know!

The post Death By Apple appeared first on Sarah Albee.

October 6, 2014

Garden of Deadly Delights

Yesterday I drove to Ithaca, New York, where I met up with Mary Smith, Professor of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University. Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine maintains a poisonous plants garden, which makes sense, if you think about it. Veterinary students need to learn to recognize plants that poison livestock. Professor Smith took a couple of hours out of her Sunday afternoon to give me a personal tour of the Poisonous Plants garden, and then as an added bonus, walked me around the Weeds garden and then the “Crops of the World” garden. She is hugely knowledgeable about plants and poisons.

I’ve been researching poisons for some months now, and it was downright thrilling to encounter the actual toxic plants after having read about them. Kind of like bumping into a famous actor on the street after you’ve just seen him playing an evil villain in a movie. Here are some of the stars of the poison plant world I met:

I’ve been researching poisons for some months now, and it was downright thrilling to encounter the actual toxic plants after having read about them. Kind of like bumping into a famous actor on the street after you’ve just seen him playing an evil villain in a movie. Here are some of the stars of the poison plant world I met:

This is poison hemlock, of the species that killed Socrates. The sign says Foxglove, but that’s for a different plant: And here’s tobacco. The pink flowers were so pretty. I was surprised by how beautiful some of these plants were.

And here’s tobacco. The pink flowers were so pretty. I was surprised by how beautiful some of these plants were. Another beautiful but oh-so-deadly one: Monkshood.

Another beautiful but oh-so-deadly one: Monkshood. Here’s snakeroot, which poisoned (and killed) Abraham Lincoln’s mother (she died of “milk sick,” an all-too-common illness of many pioneer-era people). Professor Smith explained to me that the toxin is fat soluble, so the cow can eat snakeroot and not be harmed because she excretes it in her milk. But calves and people who drink the milk can be fatally poisoned.

Here’s snakeroot, which poisoned (and killed) Abraham Lincoln’s mother (she died of “milk sick,” an all-too-common illness of many pioneer-era people). Professor Smith explained to me that the toxin is fat soluble, so the cow can eat snakeroot and not be harmed because she excretes it in her milk. But calves and people who drink the milk can be fatally poisoned. And THIS is Belladonna, aka Deadly Nighshade. I squealed when I saw it, as I hadn’t expected to see any, particularly in Ithaca, New York in early October—it’s a Mediterranean plant. It contains the alkaloid atropine, which is what makes your pupils dilate at the eye doctor’s. I don’t know if you can see those shiny black berries, but they do make for an impressively-ominous-looking plant:

And THIS is Belladonna, aka Deadly Nighshade. I squealed when I saw it, as I hadn’t expected to see any, particularly in Ithaca, New York in early October—it’s a Mediterranean plant. It contains the alkaloid atropine, which is what makes your pupils dilate at the eye doctor’s. I don’t know if you can see those shiny black berries, but they do make for an impressively-ominous-looking plant: Here’s Datura stramonium, aka Jimsonweed, aka Jamestown Weed. Lots of cool history with this plant, starting with how the Jamestown settlers purportedly slipped some of this powerful hallucinogen into the food of British officers and then watched them put proverbial lampshades on their heads for several days. Can you see the fuzzy brown pod that’s split open and showing the black interior? That’s the most toxic part.

Here’s Datura stramonium, aka Jimsonweed, aka Jamestown Weed. Lots of cool history with this plant, starting with how the Jamestown settlers purportedly slipped some of this powerful hallucinogen into the food of British officers and then watched them put proverbial lampshades on their heads for several days. Can you see the fuzzy brown pod that’s split open and showing the black interior? That’s the most toxic part. And this beautiful plant? Ricinus communus, aka the Castor bean plant. This is the plant that produces the poison ricin in its seeds. Ricin is five hundred times more toxic than arsenic or cyanide. (Fans of Breaking Bad will know this one.)

And this beautiful plant? Ricinus communus, aka the Castor bean plant. This is the plant that produces the poison ricin in its seeds. Ricin is five hundred times more toxic than arsenic or cyanide. (Fans of Breaking Bad will know this one.) Here’s Professor Smith, photographing some castor bean seeds for her students to ID on an upcoming quiz:

Here’s Professor Smith, photographing some castor bean seeds for her students to ID on an upcoming quiz: After she took the photo, she hopped up and handed me the two seeds to take home as a souvenir. It was . . . unsettling to find myself holding a potent poison in my bare hand in the middle of a field. I guess she realized I was a bit disquieted, because she pulled out a tissue and wrapped them up for me.

After she took the photo, she hopped up and handed me the two seeds to take home as a souvenir. It was . . . unsettling to find myself holding a potent poison in my bare hand in the middle of a field. I guess she realized I was a bit disquieted, because she pulled out a tissue and wrapped them up for me.

“Should I be worried about, er, you know, holding these in my bare hand?” I asked her.

“Nah,” she said, “although you’ll definitely want to wash your hands after this.”

Follow up: after I got home last night and had washed my hands until most of the soap was used up, I looked up ricin in my notes. It turns out, two castor beans are enough to kill a person if one were to chew them (or pulverize them and slip them into someone’s tea). But because the hard seed coat prevents the body from absorbing the poison, the beans can pass harmlessly through a person’s system if swallowed whole, or held in one’s hand in the middle of a field.

Follow up: after I got home last night and had washed my hands until most of the soap was used up, I looked up ricin in my notes. It turns out, two castor beans are enough to kill a person if one were to chew them (or pulverize them and slip them into someone’s tea). But because the hard seed coat prevents the body from absorbing the poison, the beans can pass harmlessly through a person’s system if swallowed whole, or held in one’s hand in the middle of a field.

The post Garden of Deadly Delights appeared first on Sarah Albee.

October 2, 2014

Let Them Eat Jiggly Soup

Back in the early nineteenth century, with populations in cities swelling, feeding the poor cheaply in poorhouses and public hospitals became a growing concern.

Back in the early nineteenth century, with populations in cities swelling, feeding the poor cheaply in poorhouses and public hospitals became a growing concern.

In her fascinating book, Gulp, Mary Roach describes the efforts of a French chemist named Jean d’Arcet, Jr., who in 1817 came up with a method for extracting gelatin from bones. I’m not sure why this was such a complicated undertaking—anyone who has ever boiled up a turkey carcass after the Thanksgiving meal would see that the resulting broth, if allowed to cool, gets all jiggly and gelatinous. But d’Arcet seems to have figured out how to reduce his “extract of bones” down to pure, concentrated gelatin.

He peddled his glop to public hospitals and poor houses, claiming that two ounces of his gelatin was equal in nutrition to three pounds of meat.

So gelatin soup became standard fare in places that fed the poor for the next twenty years, despite “criticisms and complaints.”[1] It wasn’t until 1831 that a group of physicians decided to test the gelatin soup against traditional bouillon. They found it “more distasteful, more putrescible, less digestible, less nutritious”[2] in comparison.

But not much was done, aside from forming a “Gelatin Commission.” As Roach so brilliantly puts it, “The French Academy of Sciences sprang into inaction.”[3]

It took ten more years for the Gelatin Commission to declare the gelatin soup ineffective. This after feeding it to dogs and finding the soup excited “an intolerable distaste to a degree which renders starvation preferable.”[4]

Sources:

Mary Roach, Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal, New York: WW Norton, 2013

Dawson, Percy M. A Biography of François Magendie. Brooklyn: Albert T. Huntington, 1908

[1] Dawson, 33

[2] Dawson, 33

[3] Roach, 85

[4] Dawson, 34-5

The post Let Them Eat Jiggly Soup appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 29, 2014

Fetching Names

In case you’ve recently acquired a new dog, and are wondering what to name it, look no further than the early fifteenth-century manuscript called The Master of Game. Appended at the end is a list of suitable names for your hunting dog. Here are some suggestions:

In case you’ve recently acquired a new dog, and are wondering what to name it, look no further than the early fifteenth-century manuscript called The Master of Game. Appended at the end is a list of suitable names for your hunting dog. Here are some suggestions:

Nosewise

Swepestake

Smylfeste

Trynket

Amiable

Nameles

Holdfast

Absolom

Another medieval manuscript suggests Huiiau, which doesn’t quite roll off the tongue, and Blessiau, which would invite the inevitable snide rejoinder “But I didn’t sneeze.” Still, your dog would likely be the only one at the dog park with such a historically significant name.

Then again, there’s always Max or Cooper.

Then again, there’s always Max or Cooper.

Source: Kathleen Walker-Meikle, Medieval Dogs

Images: Miniature of Canis Minor, in tables from Ptolemy's Almagest, from the British Library

Harley 2278 f. 44v Lothbrok's dog from the British Library

Detail of a miniature of a Lothbrok's dog leading a knight to Lothbrok's body. Harley 2278 f. 45v the British Library

The post appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 25, 2014

Links and Connections

For today’s post, I’m punting you to two different websites. The first is Melissa Stewart’s, where yesterday she posted a lovely review of Bugged. Here’s the link.

Having Melissa put her stamp of approval on one’s book is (practically) tantamount to getting on Oprah. She is a fantastic writer, and she knows children’s nonfiction books like no one else. Here’s the cover of her recent book, Feathers: Not Just for Flying:

And here’s Melissa’s latest book, Perfect Pairs, glowingly reviewed by Elizabeth Bird of the NYPL. It’ s about pairing fiction and nonfiction books for teaching. You should run out and buy it immediately if you are a teacher or librarian.

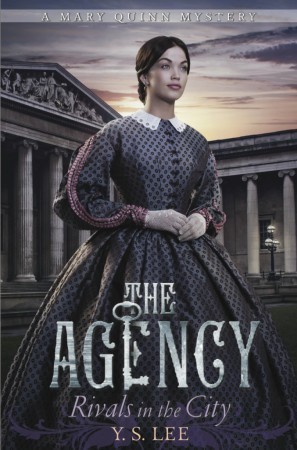

And here’s Melissa’s latest book, Perfect Pairs, glowingly reviewed by Elizabeth Bird of the NYPL. It’ s about pairing fiction and nonfiction books for teaching. You should run out and buy it immediately if you are a teacher or librarian. And the second place I’m sending you is here, to the blog post of Y.S. Lee. I posted my own account of our meet-up. This is her awesome version. Here’s the cover of Ying’s next book:

And the second place I’m sending you is here, to the blog post of Y.S. Lee. I posted my own account of our meet-up. This is her awesome version. Here’s the cover of Ying’s next book:

The post Links and Connections appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 22, 2014

Beauty Tips

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-102221

I got sidetracked in my research again. But you, Dear Reader, will be the beneficiary, because I stumbled upon a book from 1910, written by one Margaret Mixter, entitled Health and Beauty Hints, that is filled with sensible advice. Take fitness. Turns out we’ve been going about it all wrong. What, according to Ms. Mixter, is the best exercise to develop “a round, pretty figure?” Why, housework.

Yes, that’s right. Put away your running shoes. Roll up your yoga mat. Ms. Mixter maintains that “sweeping, dusting, or even washing, if the latter is not too heavy to strain the muscles, helps to strengthen and beautify the body. (207)

“Sweeping,” she continues, “is one of the best methods of rounding the arms, as well as giving correct poise. A woman whose shoulders are well thrown back, when she grasps the broom firmly, and sways her whole body, with each stroke, may add grace to her figure.”

Cornell University Library – http://publicdomainreview.org/collect...

Don’t laugh. Housework was no joke back in 1910. Stoves had to be blackened, hearths had to be swept, and carpets had to be beaten on a regular basis. The first motorized vacuum cleaner was patented and sold to William Henry Hoover in 1908, so at the time of the writing of Health and Beauty Hints, it’s unlikely that many housewives owned their own model yet. Most housewives (or their servants) must have had very round arms.

A hand-powered pneumatic vacuum cleaner, circa 1910. via Wikimedia

“Few women seem to know that a constant firm grasp of an object such as a broom or hard duster handle will round the arms,” Ms. Minter shares.

She is also brimming with suggestions for ways to whittle your waist. Here’s one: “Bending over a wash tub affects the waist line and hips to their betterment when the lean comes from the waist, and not from the shoulders.” (208)

The post Beauty Tips appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 18, 2014

Toronto!

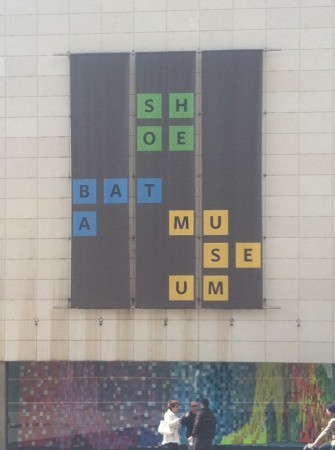

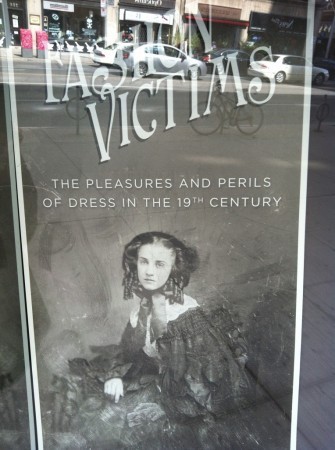

This past weekend I traveled to Toronto. I went there for two reasons: to see the exhibit called “Fashion Victims: The Pleasures and Perils of Dress in the 19th Century” at the Bata Shoe Museum, and to meet my friend Y.S. Lee.

This past weekend I traveled to Toronto. I went there for two reasons: to see the exhibit called “Fashion Victims: The Pleasures and Perils of Dress in the 19th Century” at the Bata Shoe Museum, and to meet my friend Y.S. Lee. I first heard about Ying’s books on Twitter several years ago, and after reading them, loved them so much I fan-girl friended her on Facebook. We’ve been e-friends ever since, but had never met in person. We toured the exhibit together, and then had lunch, and then Ying, who is from Canada and knows Toronto well, showed me around the city. It was a fantastic day–we talked nonstop, all the way to the last seconds as she was running to catch her train. We did manage to stop talking long enough to take this selfie:

I first heard about Ying’s books on Twitter several years ago, and after reading them, loved them so much I fan-girl friended her on Facebook. We’ve been e-friends ever since, but had never met in person. We toured the exhibit together, and then had lunch, and then Ying, who is from Canada and knows Toronto well, showed me around the city. It was a fantastic day–we talked nonstop, all the way to the last seconds as she was running to catch her train. We did manage to stop talking long enough to take this selfie: It was really fun to tour the exhibit together, because we’re both huge fans of nineteenth century fashions. (Ying has a PhD in Victorian literature, and all her books are set in 19th century London. Here’s my review of her third one. Her fourth installment is due out in February, published by Candlewick. Here’s the cover:

It was really fun to tour the exhibit together, because we’re both huge fans of nineteenth century fashions. (Ying has a PhD in Victorian literature, and all her books are set in 19th century London. Here’s my review of her third one. Her fourth installment is due out in February, published by Candlewick. Here’s the cover: I loved this pair of shoes dyed with arsenic-based green. They match exactly some arsenical green gloves I bought on ebay. You can’t see the beautiful shade of green in this photo, but trust me:

I loved this pair of shoes dyed with arsenic-based green. They match exactly some arsenical green gloves I bought on ebay. You can’t see the beautiful shade of green in this photo, but trust me: And they had some William Morris arsenical-green wallpaper. It’s not a great picture, because I wasn’t allowed to use flash:

And they had some William Morris arsenical-green wallpaper. It’s not a great picture, because I wasn’t allowed to use flash: It was cool to see these purple shoes, which were dyed with William Perkin’s brand-new invention, the first chemically-made (C26H23N4+X−), aniline dye. He called it mauveine. I thought it would be much pinker, but it’s a lovely purple. Note that the shoes are “straights,” and not made for right or left feet. And they’re all so narrow. Corns and bunions were a terrible problem.

It was cool to see these purple shoes, which were dyed with William Perkin’s brand-new invention, the first chemically-made (C26H23N4+X−), aniline dye. He called it mauveine. I thought it would be much pinker, but it’s a lovely purple. Note that the shoes are “straights,” and not made for right or left feet. And they’re all so narrow. Corns and bunions were a terrible problem.

These pink baby shoes are for a boy. Ying informed me that the traditional gender-assigned colors were reversed in the nineteenth century: pink was for boys and blue was for girls.

These pink baby shoes are for a boy. Ying informed me that the traditional gender-assigned colors were reversed in the nineteenth century: pink was for boys and blue was for girls. The exhibition runs through June of next year. Toronto is a lovely city with lots of funky neighborhoods and terrific restaurants. Well worth a visit!

The exhibition runs through June of next year. Toronto is a lovely city with lots of funky neighborhoods and terrific restaurants. Well worth a visit!

The post Toronto! appeared first on Sarah Albee.

September 15, 2014

Baby Carriers

In the first part of the nineteenth century, it was fashionable to dress babies in long petticoats to protect them from drafts.

Voluminous clothing might also help keep a child from slipping out of its mother’s or nursemaid’s arms. According to Elizabeth Ewing in her History of Children’s Costume, the first modern baby carriage in America was introduced in 1848 by Charles Burton, but it was soon banned for being a nuisance to pedestrians. He had more success opening a factory in Britain, but it wasn’t until the 1870s that a pram was created where a baby could lie down. So prior to 1870, babies had to be carried.

Voluminous clothing might also help keep a child from slipping out of its mother’s or nursemaid’s arms. According to Elizabeth Ewing in her History of Children’s Costume, the first modern baby carriage in America was introduced in 1848 by Charles Burton, but it was soon banned for being a nuisance to pedestrians. He had more success opening a factory in Britain, but it wasn’t until the 1870s that a pram was created where a baby could lie down. So prior to 1870, babies had to be carried. A well-nourished 18-month-old weighed an average of 26 pounds. (Quick aside: Have a look at these next two pictures: the first one really gives you a sense of the baby’s heft. The mother in the second one doesn’t seem to be straining to hold that kid at all.)

A well-nourished 18-month-old weighed an average of 26 pounds. (Quick aside: Have a look at these next two pictures: the first one really gives you a sense of the baby’s heft. The mother in the second one doesn’t seem to be straining to hold that kid at all.)

By the 1870s, you start to see baby prams in paintings. The impressionists seemed fond of painting them. Here’s Degas:

By the 1870s, you start to see baby prams in paintings. The impressionists seemed fond of painting them. Here’s Degas: and Gauguin:

and Gauguin: and here’s a later model, 1913. It’s such a sweet picture, isn’t it?

and here’s a later model, 1913. It’s such a sweet picture, isn’t it?

LOC 708611913

The post Baby Carriers appeared first on Sarah Albee.