R. Joseph Hoffmann's Blog: Khartoum, page 25

December 22, 2013

Tea Party Challenge

Anyone can take this little quiz. But since the TP is especially fond of early America, they should be able to score 100% without Googling a single answer. If you score less than 70%, you have to take a Democrat for sushi.

AMERICAN HISTORY BEFORE 1800

1. In what year was the United States Constitution adopted?

2. The French Revolution was fought before or after the American War of Independence.

3. Name two Europeans who were directly involved in strategic planning for the American Revolution.

4. What was Tom Paine’s nationality?

5. State one reason for John Adams not being a slaveholder.

6. What is the subject of the Third Amendment to the US Constitution?

7. Maryland was founded as a Methodist colony: True or False?

8. How many university level colleges existed in the American colonies before 1710; name one.

9. Only in the nineteenth century, with Zachary Taylor, did presidents begin to swear the oath of office on a Bible (True or False)

10. What is the reason for showing the profile of a famous patriot or president on the coinage of the United States?

11. What does the world “republic” mean?

12. Which amendment to the US Constitution provides for the direct election of senators?

13. Cite three of the main themes of the Federalist papers.

14. What is the highest elective rank ever attained by Benjamin Franklin?

15. The flag of what mercantile company of the late 17th century served as the model for the US flag?

16. State in one sentence the difference between a pilgrim and a puritan.

17. How was the Massachusetts Bay Colony politically and economically distinct from the Virginia colony?

18. Who fought in the French and Indian War?

19. Who was Anne Hutchinson (d.1643?

20. True or false: By 1810, the United States had become the largest slave exporting nation in the world.

21. The so-called Pledge of Allegiance was not written until 1892.

22. What was the extent of the United States in 1800?

23. What does the word “commonwealth” mean? What states retain the title?

24. What article of the Constitution specifies the oath to be taken by a president?

25. The First Amendment to the Constitution prohibits Congress from creating a state religion; what else does the same amendment do?

AMERICAN HISTORY BEFORE 1800

1. In what year was the United States Constitution adopted?

2. The French Revolution was fought before or after the American War of Independence.

3. Name two Europeans who were directly involved in strategic planning for the American Revolution.

4. What was Tom Paine’s nationality?

5. State one reason for John Adams not being a slaveholder.

6. What is the subject of the Third Amendment to the US Constitution?

7. Maryland was founded as a Methodist colony: True or False?

8. How many university level colleges existed in the American colonies before 1710; name one.

9. Only in the nineteenth century, with Zachary Taylor, did presidents begin to swear the oath of office on a Bible (True or False)

10. What is the reason for showing the profile of a famous patriot or president on the coinage of the United States?

11. What does the world “republic” mean?

12. Which amendment to the US Constitution provides for the direct election of senators?

13. Cite three of the main themes of the Federalist papers.

14. What is the highest elective rank ever attained by Benjamin Franklin?

15. The flag of what mercantile company of the late 17th century served as the model for the US flag?

16. State in one sentence the difference between a pilgrim and a puritan.

17. How was the Massachusetts Bay Colony politically and economically distinct from the Virginia colony?

18. Who fought in the French and Indian War?

19. Who was Anne Hutchinson (d.1643?

20. True or false: By 1810, the United States had become the largest slave exporting nation in the world.

21. The so-called Pledge of Allegiance was not written until 1892.

22. What was the extent of the United States in 1800?

23. What does the word “commonwealth” mean? What states retain the title?

24. What article of the Constitution specifies the oath to be taken by a president?

25. The First Amendment to the Constitution prohibits Congress from creating a state religion; what else does the same amendment do?

Published on December 22, 2013 19:35

•

Tags:

tea-party-quiz-history-of-the-us

The Mirage

Then we ascended to the second heaven. A voice asked, ‘Who is it?’ Jibreel said, ‘Jibreel.’ Then the voice said, ’Who is with you?’ He said, ‘Muhammad’ Then came the voice again, , ‘Has he been sent for?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ It was said, ‘He is welcomed. What a wonderful visit is this!” Then I met Isa and Yahya who said, ‘You are welcomed, O brother and a Prophet.’ Sahih al-Bukhari, volume 4,Book 54, Hadith number 429

He rises and begins to round, / He drops the silver chain of sound (Meredith)

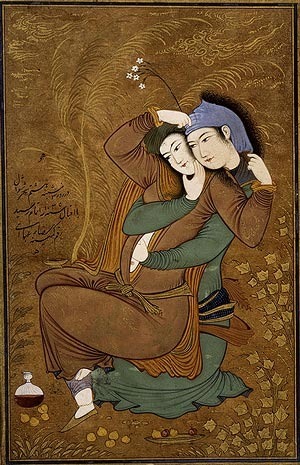

Omnia vincit Amor: et nos cedamus Amori.” (Vergil, Eclogue 10)

Lailat al Mi’raj

My arms about you

we rise like incense rises,

like Jesus (they say) rose–

touching Satan’s cloak–

above the evening clouds to view

all the kingdoms of earth

golden before him:

his stomach knotted,

teetering on the

edge of the highest high

mountain, so high

that to look down made

even a god dizzy with power.

Rise like the lark ascending

into the gray English skies

fluttering in darts and fits

first to sight, then barely visible

and then like a hell-kite

at one fell swoop down, down—

from beauty to despair.

I take my arms away.

We are unlocked

and the soul that rose with you

falls hard to earth, shorn from

the wings that bore it,

the pinions that for a moment

took us to the Lote tree,

the garden of refuge,

where choirs of angels

praise Allah

ceaselessly.

Published on December 22, 2013 10:44

•

Tags:

hafiz, islamic, persian, poetry, r-joseph-hoffmann

December 20, 2013

The Dumb as a Doorknocker Atheist Attack on Jesus

"...But what really irks me at this time of year is the way they have taken to picking on Jesus. A slim majority have bought into the idea that Jesus never existed because they have already bought into the idea that God doesn’t exist. Maybe if they go far enough with this historical and philosophical skepticism they will reach some critical, Cartesian point of wondering about their own reality. But their incipient pyrhhonism aside, they simply can’t make up their mind whether to support the thoroughgoing mythical school of thought or punch holes in the “supernaturalism” of an otherwise historical record. To do that, they would first need to distinguish between metaphysical propositions like “There is a God”, historical assertions, such as the idea that Jesus really existed, and theological doctrines such as the statement that Jesus was God. I see no race among atheists to make such distinctions. They end up sounding more like Elmer Fudd on finding a rabbit hole empty: Jesus cannot be the son of God because God doesn’t exist so it is entirely plausible that he didn’t exist either...." Read more

Published on December 20, 2013 01:22

December 19, 2013

Holiness

“Then do they not look at their camels, how they are created—and at the sky, how is it raised? ” (Qur’an al-Ghashiyah,17-18)

In Bahry, near the dry parts of Khartoum,

men in jalabiya with sticks for swords

turn their tunics to pantaloons

and ride on sneering camels towards

the Nile. One or two tourists

snap pictures of the spectacle

knowing, of course, it isn’t the purest

(or, for all that, the most historical)

reflection of an ancient ritual.

But still they race, children at recess

pushing and digging to be the winner,

like a dancing girl, the wishful princess

who plays the part and ends a sinner.

They race because they are broken.

They race because they are afraid to die.

They race because once it was forespoken

that they might in racing reach the sky.

R. Joseph Hoffmann

Published on December 19, 2013 08:01

December 18, 2013

Neanderthal Death and Dying

I was just reading an article about Neanderthals burying their dead, a practice which will further humanize them and cause us to see them not as higher apes but close cousins.

The idea that something so like us lived in our own era and became extinct, like Barbary Lions and Arctic camels, should be troubling for us, because it points not just to survival as an iron law of nature, but to the fact that like any other animal species we are subject to the vicissitudes of cultural and environmental change. In the death of Neanderthal we confront the general mortality of our own race. And though we shall never know, we may also confront the murderous superiority of human intelligence over theirs. Homo sapiens sapiens might have warred them to extinction, or they may simply have succumbed to disease or demographic decline.

We are more comfortable exploring the outreaches of space and the depth of the oceans for possible and unusual life forms than we are with probing the depths of the self because such activity distracts us from our own puny and limited existence.

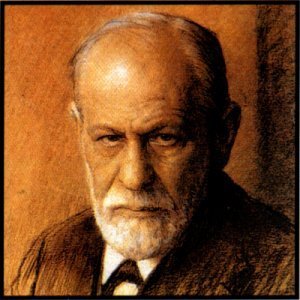

There is nothing new about saying this; Freud would say it is just a spin on his theory of “substitutionary satisfaction,” except that instead of locating satisfaction in the arts and merchandisable skills that define civilization, as he tended to do, it locates it specifically in the objects we choose for scientific investigation: the outer world—the world external to the self. The inner world, now being dramatically explored by studies in cognition and neuroscience is more putative, perhaps even more real for certain people than for others. We have to acknowledge that the inner life of a stockbroker and the inner life of a classical musician or philosopher are different not just as a matter of preference or taste but as matter of fundamental interpretation and meaning. The world in which we become the object of our own thought is fraught with difficulty, not least of which is the ancient problem of how to define the self.

You may recall this famous passage from Hobbes,describing earliest human history before “governments” were formed:

"Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of Warre, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short."

In other words, it is remarkable that we survived at all, perhaps more so that the instinctive drive for survival has stretched our intelligence to devise new ways to ensure our persistence, and in some ways, our progress. Hobbes would define progress, as men of the Enlightenment would, as the removal of the “natural condition” of continual fear, and danger, of violent death--and just as important, the birth of societies that extend our life and our dominion over nature. An astounding number of our contemporaries still define progress in that way.

Still, whatever collective progress is, at the end of it is death. Not death as Neanderthal may have experienced it—the gradual but no doubt perceptible diminution of creatures who looked like them down to the last half dozen on the face of the earth. But individual death.

Freud had a few thoughts on this in a 1915 treatise called Thoughts for the Times on War and Death, written a few months after the outbreak of the Great War. In that treatise Freud lets his imagination range more freely than usual, speculating about everything from cognition to the unconscious to polyarchy (constant, universal warfare)to the psychological foundations for burying the dead.

Like Freud or lump him, his thoughts never fail to arouse the suspicion of truth: Do we bury our dead because they attract animals and flies, begin to smell bad, or because we want them safely under the ground where they cannot remind us of our fate and torment us through their jinns? Is (as Hobbes suggests) the natural state of mankind war and the artificial state (as Freud argues) peace and civilization? Is religion a contract between these two extremes, a denial of death through harnessing violence (taboos, laws) in the name of deferred life after death?

Is the ritual violence that we sublimate in religious practices such as the Eucharist and circumcision and even the ideological form of jihad a reminder of our essentially hateful and violent natures? How do we survive, as creatures torn between the need to make love and the reality of decay? Can we even imagine our death?

"We cannot, indeed, imagine our own death; whenever we try to do so we find that we survive ourselves as spectators. The school of psychoanalysis could thus assert that at bottom no one believes in his own death, which amounts to saying: in the unconscious every one of us is convinced of his immortality."

Or is this too outrageous a simplification of the complex reality we live as human beings? Was Neanderthal more in touch with basic impulses that define an essential humanity, a kind of lost reality that civilization, art, music, science, and literature have taken from us?

Wilfrid Owen asks the question poetically about the general violence of war and the meaning of death, the same war Freud was responding to as a psychoanalyst three years earlier:

"Was it for this the clay grew tall?

—O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth's sleep at all?" (“Futility,”1918)

Published on December 18, 2013 10:51

•

Tags:

death-and-dying, neandethal, r-joseph-hoffmann

December 15, 2013

Outdumbing Each Other

Like the rest of you, I am addicted to politics. As I look back, I'm depressed by the fact that most of my life has been riddled with political disappointment, ranging from the Kennedy and King assassinations of my youth to the useless wars (are any "useful"?) of my recent adult life.

Once upon a young time I probably thought politicians were smarter than me, and that a few bad eggs caused all the problems. America was basically a shining star, but a few bad guys made everything around us ugly and spoiled the bright and shining future that Camelot foretold. But remember: Not everyone in Washington wanted to go to the moon, and not everyone wanted a Civil Rights act. I can't speak for future moon visits, but I can name a number of people in Congress who would vote to repeal every piece of progressive legislation passed since the New Deal, beginning with the Affordable Care Act.

Now that I am older, I don't think politicians are smart. I think I am smarter than almost anyone in Congress. Most of my friends could not begin to contemplate a "career" in American politics. Instead of public service, they regard political life as public circus. In fact most of our addiction comes not from any belief that we are watching democracy at work but that we are watching the clowns from the stands.

It's tempting to think that Camelot was the norm in America, but they don't call it Camelot for no reason: It was one brief, shining moment followed by war, plunder, murder, and intellectual desuetude.

The norm between the early nineteenth century and today has been the kind of yahooism that Mencken called government by the Booboisie in 1922. Things are bad now, but they have never been much better.

If they seem worse now, at least to some of us, it is because we have become a country separated by books. The information age has left politicians free to pursue their interest in the stock market, opinion surveys, and soft porn. It has not caused them to read more history, literature, politics or science. The bookish democracy of the founders has been entrusted to bookless men who simply try to outdumb each other in language that would make a Jefferson or Franklin retch.

With a few modern presidential exceptions like the Roosevelts, Woodrow Wilson, Kennedy, Clinton and Obama, our presidents have not been especially bookish. All of the ones I just mentioned were Ivy leaguers, one a former president of Princeton. But frontier America after the time of Jackson and Taylor never made book larnin' a requirement for political office, and in Congress it has become a liability.

That is what the Tea Party is all about. It is why Ivy-educated Ted Cruz feels warm in the company of thick-as-a plank Sarah Palin in the dumber-than- thou games--the one who has never read a book front to back, and the other who has to pretend not to have, or lose his "base." That's the beauty of America--an electorate that can say, "That Cruz is alright, even though he did go to Princeton or something." Being educated and book-loving, at least obviously educated and loving books, is a huge liability, a challenge to be overcome.

The ideal American statesman is Lincoln: self-taught, self-reliant, self-effacing. But the fact is, Lincoln read what he could and didn't pretend to be folksy. His language was influenced by the best poetry and prose he could get his hands on. He admired rhetoric, even if his voice never rose to the tropes he invented. The same is true I recently discovered of Truman, a humble Missouri haberdasher, and of the supremely inarticulate Eisenhower. They quoted poetry from memory, liked classical music, wrote letters home to their sweeties and fiancées about books they wanted to read when they got home.

Clinton, W, and the g-dropping Obama, are studiously folksy. They have been told not to be Michael Dukakis and not to be John Kerry. They have been told that their Ivy League credentials are burdens in most voting districts. They have to sound not like John Kennedy, who never changed his Brookline dialect for anyone, but like LBJ, who wasn't nearly as stupid as his Texas drawl made him sound.

I deplore the fact that our politicians try to out-stupid each other: "My opponent says he's never read a book. Well I can tell the American people right now, I have never even held one in my hands...

The real casualty of homespun, cornpone politics is that it not only doesn't make the American politician Lincoln or Zachary Taylor. It doesn't even make him a convincing impersonator.

It makes grim sense for a president, including this one, to pretend he would be just as happy drinking cactus juice and herding cattle as running a country (the George W Bush trope) and to think that no one else in the world is watching us.

They do watch--in Europe, in China and Russia, and places far flung and in between--places where books are read and language is part of the national patrimony. And they worry that the World Power tries so hard to act dumb.

Once upon a young time I probably thought politicians were smarter than me, and that a few bad eggs caused all the problems. America was basically a shining star, but a few bad guys made everything around us ugly and spoiled the bright and shining future that Camelot foretold. But remember: Not everyone in Washington wanted to go to the moon, and not everyone wanted a Civil Rights act. I can't speak for future moon visits, but I can name a number of people in Congress who would vote to repeal every piece of progressive legislation passed since the New Deal, beginning with the Affordable Care Act.

Now that I am older, I don't think politicians are smart. I think I am smarter than almost anyone in Congress. Most of my friends could not begin to contemplate a "career" in American politics. Instead of public service, they regard political life as public circus. In fact most of our addiction comes not from any belief that we are watching democracy at work but that we are watching the clowns from the stands.

It's tempting to think that Camelot was the norm in America, but they don't call it Camelot for no reason: It was one brief, shining moment followed by war, plunder, murder, and intellectual desuetude.

The norm between the early nineteenth century and today has been the kind of yahooism that Mencken called government by the Booboisie in 1922. Things are bad now, but they have never been much better.

If they seem worse now, at least to some of us, it is because we have become a country separated by books. The information age has left politicians free to pursue their interest in the stock market, opinion surveys, and soft porn. It has not caused them to read more history, literature, politics or science. The bookish democracy of the founders has been entrusted to bookless men who simply try to outdumb each other in language that would make a Jefferson or Franklin retch.

With a few modern presidential exceptions like the Roosevelts, Woodrow Wilson, Kennedy, Clinton and Obama, our presidents have not been especially bookish. All of the ones I just mentioned were Ivy leaguers, one a former president of Princeton. But frontier America after the time of Jackson and Taylor never made book larnin' a requirement for political office, and in Congress it has become a liability.

That is what the Tea Party is all about. It is why Ivy-educated Ted Cruz feels warm in the company of thick-as-a plank Sarah Palin in the dumber-than- thou games--the one who has never read a book front to back, and the other who has to pretend not to have, or lose his "base." That's the beauty of America--an electorate that can say, "That Cruz is alright, even though he did go to Princeton or something." Being educated and book-loving, at least obviously educated and loving books, is a huge liability, a challenge to be overcome.

The ideal American statesman is Lincoln: self-taught, self-reliant, self-effacing. But the fact is, Lincoln read what he could and didn't pretend to be folksy. His language was influenced by the best poetry and prose he could get his hands on. He admired rhetoric, even if his voice never rose to the tropes he invented. The same is true I recently discovered of Truman, a humble Missouri haberdasher, and of the supremely inarticulate Eisenhower. They quoted poetry from memory, liked classical music, wrote letters home to their sweeties and fiancées about books they wanted to read when they got home.

Clinton, W, and the g-dropping Obama, are studiously folksy. They have been told not to be Michael Dukakis and not to be John Kerry. They have been told that their Ivy League credentials are burdens in most voting districts. They have to sound not like John Kennedy, who never changed his Brookline dialect for anyone, but like LBJ, who wasn't nearly as stupid as his Texas drawl made him sound.

I deplore the fact that our politicians try to out-stupid each other: "My opponent says he's never read a book. Well I can tell the American people right now, I have never even held one in my hands...

The real casualty of homespun, cornpone politics is that it not only doesn't make the American politician Lincoln or Zachary Taylor. It doesn't even make him a convincing impersonator.

It makes grim sense for a president, including this one, to pretend he would be just as happy drinking cactus juice and herding cattle as running a country (the George W Bush trope) and to think that no one else in the world is watching us.

They do watch--in Europe, in China and Russia, and places far flung and in between--places where books are read and language is part of the national patrimony. And they worry that the World Power tries so hard to act dumb.

Published on December 15, 2013 06:24

•

Tags:

anti-intellectualism, books, education, obama, politics, r-joseph-hoffmann, reading

December 14, 2013

Incarnation

I have spent a load of time at New Oxonian kvetching about new atheists. Now everyone's doing it, but I was one of the the first kvetchioners. And I paid a high price, having the distinction of being abused and scolded and insulted by critics as far removed as a is from b in ideological variety: Jerry Coyne, P Z Myers, Eric MacDonald, sundry literary lieutenants and former friends, and their "base." Especially their base.

I have always called myself a soft unbeliever. I am not committed to unbelief. I am not a none. I am not agnostic--a word that always evokes in my imagination an incurable sinus condition.

Given the contours of today's young, restless, and largely illiterate atheism, I am not an atheist.

I am just not sure about the God thing. Doctrines and dogmas are really only interesting as historical information, or because they tell us something about the journey of the human mind from one kind of truth to another: truth as a higher good to be sought purely in the mind, and truth as an answer to questions and solutions to problems of existence. One gets us philosophy, music, pure mathematics and poetry; the second gets us science and technology. Don't believe them when they try to harness "reason" to the second.

I am genetically incapable of taking up or down votes on truth; so I find embedded in some religious doctrines --the Trinity for example--some important insights into how the imagination launches itself almost unwillingly towards questions of transcendence and immanence.

Translated into my own feeble language, that means that while I am not sure about God, people have never been willing to leave God alone--as a purely distant thing. A God who is believed to exist can't just exist as a cardinal principle. The "divine Mechanic" of Newton and Alexander Pope and the God of the Philosophers looks a lot like the beautifully made scientific instruments of the eighteenth century: he is wonderful insofar as we are supremely competent to solve the mysteries of nature through the gift of reason.

But the majority of people never latched on to that God, and no wonder. Because he was nothing like the majority of people. They were happy enough with a God who variously demands obedience, faith, trust--in cruel and tormenting ways; but who in a different spin loves, cajoles, inspires, teaches, and takes our place by becoming just like us. Greater love than this hath no man. Who doesn't tremble at words like that?

It is almost Christmas. I may be wrong, but Christmas is frighteningly magical and mysterious. No wonder people feel lonely in the midst of their families, and unloved in the act of receiving gifts. Christmas is that place where the expectation of happiness confronts the reality of human sadness, where joy to the world means the judgment of mankind.

It is a time of unforced reflection, fraught with memories of family feuds, the first social awareness of missing family members, presents you wanted but never got. You see in the faces of expectant children the anxiety of age.

Somewhere in the background is the central myth of the birth of Jesus, the "nativity of the Lord," or in official language--seldom used even by priests these days--the incarnation.

Atheists often despise Christmas. Their anti-religion billboard campaigns you'll notice don't target Muslims but the Christian holiday season. Partly this may just be common sense on their part: Muslims are not famous for responding to slaps in the face by turning the other cheek. But the birth of the baby who became the man who taught people to do just that seems especially venomous to the atheist. Why?

Because you can live without a pie in the sky God by a simple act of negation, by scorn, ridicule, 'blasphemy' or denial. But how can you ignore a baby in a manger lined with hay?

But atheists have never bothered to understand the incarnation. It is not the simple Hellenistic belief that sometimes, if rarely, gods are born on earth. Unbelief becomes more problematical when it's suggested that "God became man," when belief takes on a Trinitarian aspect that includes other components of human personality. Freud may not have known that he was borrowing shamelessly from this tradition when he developed his model of the human psyche; but his rival Karl Jung reminded him of it. (To which Freud responded, Unsinn)

Freud wasn't into the Christ child, but once a year many people are--into celebrating the long liturgical action that begins here and ends on Good Friday. The celebration of an existence within which (to quote the church father Irenaeus) "all human nature is summarized."

"God became man so that we might become God," the Egyptian writer Athanasius declared in the fourth century. In that statement the centuries long war between pagan religion and the new faith was resolved; the gods are no longer at war with mankind. Men have been elevated to divinity by a God who confers his own nature on them. This is the language of myth, of course; but the phenomenon it describes would have profound effects on the later history of western civilization.

It begins with the belief that the child Jesus is the prototype of all human nature, born to be godlike in all respects, and born to be human "in all things but sin." No wonder, with that teaching, emperor after emperor and critic after critic called the Christians "atheists." They had destroyed the barrier between heaven and earth.

That kind of atheism makes us nervous, too, because it is grounded in affirmation, not denial: it leaves us alone in a world in which we are as vulnerable as a new born baby as he takes his first puffs of air, or as isolated as a man struggling for breath on a cross.

You can billboard these images, if you want. You can deny Jesus existed--there a slim rise in the number of eccentrics who do--but the symbolic weight of this story is greater than anything human history has produced.

Merry Christmas from Khartoum, on the Nile where Moses once floated in a basket made of reeds.

I have always called myself a soft unbeliever. I am not committed to unbelief. I am not a none. I am not agnostic--a word that always evokes in my imagination an incurable sinus condition.

Given the contours of today's young, restless, and largely illiterate atheism, I am not an atheist.

I am just not sure about the God thing. Doctrines and dogmas are really only interesting as historical information, or because they tell us something about the journey of the human mind from one kind of truth to another: truth as a higher good to be sought purely in the mind, and truth as an answer to questions and solutions to problems of existence. One gets us philosophy, music, pure mathematics and poetry; the second gets us science and technology. Don't believe them when they try to harness "reason" to the second.

I am genetically incapable of taking up or down votes on truth; so I find embedded in some religious doctrines --the Trinity for example--some important insights into how the imagination launches itself almost unwillingly towards questions of transcendence and immanence.

Translated into my own feeble language, that means that while I am not sure about God, people have never been willing to leave God alone--as a purely distant thing. A God who is believed to exist can't just exist as a cardinal principle. The "divine Mechanic" of Newton and Alexander Pope and the God of the Philosophers looks a lot like the beautifully made scientific instruments of the eighteenth century: he is wonderful insofar as we are supremely competent to solve the mysteries of nature through the gift of reason.

But the majority of people never latched on to that God, and no wonder. Because he was nothing like the majority of people. They were happy enough with a God who variously demands obedience, faith, trust--in cruel and tormenting ways; but who in a different spin loves, cajoles, inspires, teaches, and takes our place by becoming just like us. Greater love than this hath no man. Who doesn't tremble at words like that?

It is almost Christmas. I may be wrong, but Christmas is frighteningly magical and mysterious. No wonder people feel lonely in the midst of their families, and unloved in the act of receiving gifts. Christmas is that place where the expectation of happiness confronts the reality of human sadness, where joy to the world means the judgment of mankind.

It is a time of unforced reflection, fraught with memories of family feuds, the first social awareness of missing family members, presents you wanted but never got. You see in the faces of expectant children the anxiety of age.

Somewhere in the background is the central myth of the birth of Jesus, the "nativity of the Lord," or in official language--seldom used even by priests these days--the incarnation.

Atheists often despise Christmas. Their anti-religion billboard campaigns you'll notice don't target Muslims but the Christian holiday season. Partly this may just be common sense on their part: Muslims are not famous for responding to slaps in the face by turning the other cheek. But the birth of the baby who became the man who taught people to do just that seems especially venomous to the atheist. Why?

Because you can live without a pie in the sky God by a simple act of negation, by scorn, ridicule, 'blasphemy' or denial. But how can you ignore a baby in a manger lined with hay?

But atheists have never bothered to understand the incarnation. It is not the simple Hellenistic belief that sometimes, if rarely, gods are born on earth. Unbelief becomes more problematical when it's suggested that "God became man," when belief takes on a Trinitarian aspect that includes other components of human personality. Freud may not have known that he was borrowing shamelessly from this tradition when he developed his model of the human psyche; but his rival Karl Jung reminded him of it. (To which Freud responded, Unsinn)

Freud wasn't into the Christ child, but once a year many people are--into celebrating the long liturgical action that begins here and ends on Good Friday. The celebration of an existence within which (to quote the church father Irenaeus) "all human nature is summarized."

"God became man so that we might become God," the Egyptian writer Athanasius declared in the fourth century. In that statement the centuries long war between pagan religion and the new faith was resolved; the gods are no longer at war with mankind. Men have been elevated to divinity by a God who confers his own nature on them. This is the language of myth, of course; but the phenomenon it describes would have profound effects on the later history of western civilization.

It begins with the belief that the child Jesus is the prototype of all human nature, born to be godlike in all respects, and born to be human "in all things but sin." No wonder, with that teaching, emperor after emperor and critic after critic called the Christians "atheists." They had destroyed the barrier between heaven and earth.

That kind of atheism makes us nervous, too, because it is grounded in affirmation, not denial: it leaves us alone in a world in which we are as vulnerable as a new born baby as he takes his first puffs of air, or as isolated as a man struggling for breath on a cross.

You can billboard these images, if you want. You can deny Jesus existed--there a slim rise in the number of eccentrics who do--but the symbolic weight of this story is greater than anything human history has produced.

Merry Christmas from Khartoum, on the Nile where Moses once floated in a basket made of reeds.

Published on December 14, 2013 11:14

•

Tags:

atheism, bible, christianity, mythology, r-joseph-hoffmann, religion

December 13, 2013

Winter

Cold--sort of--has swept into the desert and along the banks of the Nile. It snowed in Jerusalem. Can you believe it? We just finished learning that all that stuff about Jesus trembling for cold in December was crap because it's never cold in this part of the world. Well, guess what: he coulda been cold. That is, if the story is true--which is a different topic.

What do I do on Khartoum mornings? I wake up early. I pray. I am trying on Islam to see if it fits. I know that makes my motivation questionable. Sometimes I pray for one less (fewer) muezzin but there always seems to be one more, blending into a kind of atonal polyphony that sounds like male cats at mating time. It can't be a sound God likes to hear. Not all Islamic music sounds this way. Just what I get to hear at five a.m. Sometimes I pray for Omnia.

I make coffee. With cardamom. Splendid, but not as good as you can get on the street from the ubiquitous tea ladies.

I shower, usually under a dribble of semi-warm water that leaves me feeling unfinished. On the hot days, it doesn't matter--but today with the temperature hovering around 40F, I could use a little heat with my ablutions.

I leave the house, driving myself, in my own car--in Khartoum. If this does not sound like bravery, nay potential martyrdom to you, you have never driven here. I have decided that the reason they gave me the car was to ensure my death without going to the trouble of kidnapping and feeding me for nine months. Now you see why Reluctant Fundamentalist is such a good book. The author is Moshin Hamid. Haven't seen the film and may not.

What do I do on Khartoum mornings? I wake up early. I pray. I am trying on Islam to see if it fits. I know that makes my motivation questionable. Sometimes I pray for one less (fewer) muezzin but there always seems to be one more, blending into a kind of atonal polyphony that sounds like male cats at mating time. It can't be a sound God likes to hear. Not all Islamic music sounds this way. Just what I get to hear at five a.m. Sometimes I pray for Omnia.

I make coffee. With cardamom. Splendid, but not as good as you can get on the street from the ubiquitous tea ladies.

I shower, usually under a dribble of semi-warm water that leaves me feeling unfinished. On the hot days, it doesn't matter--but today with the temperature hovering around 40F, I could use a little heat with my ablutions.

I leave the house, driving myself, in my own car--in Khartoum. If this does not sound like bravery, nay potential martyrdom to you, you have never driven here. I have decided that the reason they gave me the car was to ensure my death without going to the trouble of kidnapping and feeding me for nine months. Now you see why Reluctant Fundamentalist is such a good book. The author is Moshin Hamid. Haven't seen the film and may not.

Published on December 13, 2013 20:25

•

Tags:

r-joseph-hoffmann

Khartoum

Khartoum is a site devoted to poetry, critical reviews, and the odd philosophical essay.

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

Khartoum is a site devoted to poetry, critical reviews, and the odd philosophical essay.

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

...more

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

Khartoum is a site devoted to poetry, critical reviews, and the odd philosophical essay.

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

...more

- R. Joseph Hoffmann's profile

- 48 followers