R. Joseph Hoffmann's Blog: Khartoum, page 18

April 11, 2015

By Marx - Engels

"Inexorable" applied to love

means unescapable

but to sadness

unrelenting.

About sadness we know

a thing or two.

There is the sadness

each time I see you

and the sadness

when you walk away.

We hope for joy between,

inexorably we hope

to be released

but it will not come

because in between

there is us

and on either side, you

and what is left of me

that does not still

belong to you.

It is not much, now that you

have become everything,

but most of all

the sadness.

means unescapable

but to sadness

unrelenting.

About sadness we know

a thing or two.

There is the sadness

each time I see you

and the sadness

when you walk away.

We hope for joy between,

inexorably we hope

to be released

but it will not come

because in between

there is us

and on either side, you

and what is left of me

that does not still

belong to you.

It is not much, now that you

have become everything,

but most of all

the sadness.

Published on April 11, 2015 01:43

April 5, 2015

For You, John Donne

Give me the beauty that doth two embrace,

Not one all by herself to set the score,

The dark epistemology of heart and face

In Conflict bent for Conflict loved--not more.

Give me the aspiration of thine eye

Trained on such targets as both hearts despise,

Without perceiving what time spent might buy

Or what the cost to holiness implies.

Or give me nothing of yourself at all,

Not body, wit, or grace--not passion sweet

Nor tender words that mitigate the fall

I fell when first I saw in you my fate.

For this goodbye I think the angels weep

And devils satisfied do soundly sleep,

Published on April 05, 2015 10:36

March 25, 2015

A Word

Let there be silence

for God did not create noise.

No he created music and interval

and the quiet space between

us where every word is an offense

against purity and every worldly

beauty that is not you

is the lie.

And yes blindness to

the world, your gift to me

and this imperfect silence

I give you as it was

in the beginning, a small

and shining star.

for God did not create noise.

No he created music and interval

and the quiet space between

us where every word is an offense

against purity and every worldly

beauty that is not you

is the lie.

And yes blindness to

the world, your gift to me

and this imperfect silence

I give you as it was

in the beginning, a small

and shining star.

Published on March 25, 2015 10:23

February 21, 2015

The Muse Retiring

Methinks I must my muse destroy:

She giveth hardship never joy.

I seek the edge, the thought supernal--

She giveth only pastures vernal.

I say, 'Diana' (such I name her

And praise when I could ver'ly blame her)

'Give this swain thine inspiration.

Take away this constipation.'

'Scab', saith she, 'the shit you scrawl

Is not my doing, not at all,

But thine entirely--art so banal

'Tis praise indeed to call it anal.'

'Begone,' I say, 'Diana fair,

For foul thou very dost me here!

To call my art so gross as shit.'

'You can't fire me,' saith she, 'I quit'.

She giveth hardship never joy.

I seek the edge, the thought supernal--

She giveth only pastures vernal.

I say, 'Diana' (such I name her

And praise when I could ver'ly blame her)

'Give this swain thine inspiration.

Take away this constipation.'

'Scab', saith she, 'the shit you scrawl

Is not my doing, not at all,

But thine entirely--art so banal

'Tis praise indeed to call it anal.'

'Begone,' I say, 'Diana fair,

For foul thou very dost me here!

To call my art so gross as shit.'

'You can't fire me,' saith she, 'I quit'.

Published on February 21, 2015 04:42

January 29, 2015

The Story of Man

We all begin in what we end

since from the Garden we did wend

and traded pineapples for thorn

and turned God's care for us to scorn.

Sad, isn't it, this morbid turn

from Paradise, from man to worm.

From clay to clay, and dust to dust

we drearily pursue our Must.

God only said "You must not eat

this special fruit, so succulent,

that angels longed to keep it near.

But I said No, I'll plant it here.

I built this garden to conceal it

so that the serpent couldn't steal it.

I did this at extreme expense,

in spite of my omniscience.

I put you here as guard and guardess.

But frankly dears you've made a mess:

Now every one will want a nosh

I really wish I'd planted squash."

So spake poor God, so much betrayed--

The one who worlds and creatures made.

He flung them out the garden gate

and warned them, they should never mate

Or else there would be hell to pay.

And pay they did, along the way,

in pain and sorrow, care and worry

But that methinks's another story.

Published on January 29, 2015 21:17

January 22, 2015

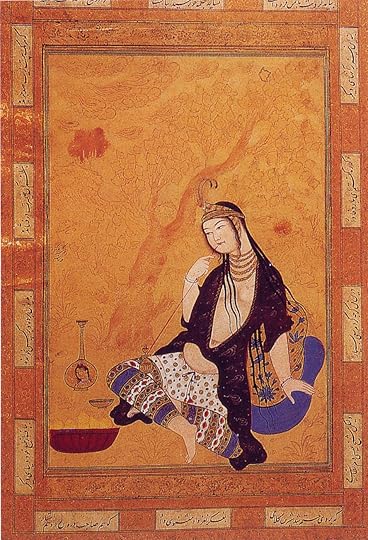

Rabia

I remember the sweat

like cardamom sweet

and your eyes my god

that could not cry

and the lies you told

and could not tell

because you thought

he knows my lies

I said my sweet the sufi

call to visions

we cannot apprise.

And until then we dance

we twirl to rhythm

only God unfurls.

And in the end

when spinning ceases

We are the victims

of our seasons.

like cardamom sweet

and your eyes my god

that could not cry

and the lies you told

and could not tell

because you thought

he knows my lies

I said my sweet the sufi

call to visions

we cannot apprise.

And until then we dance

we twirl to rhythm

only God unfurls.

And in the end

when spinning ceases

We are the victims

of our seasons.

Published on January 22, 2015 04:41

January 12, 2015

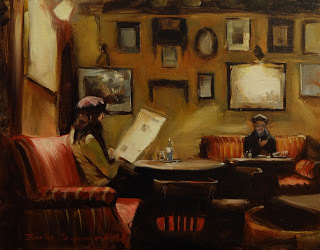

Étude at Cafe Hawelka

I want a flat near enough

the Café Hawelka on the Dorotheergasse

to come every day

and find you there sipping

the darkest Viennese coffee and reading

--I don’t know--Pushkin's Tsar Saltan.

You will not look up when I enter,

and I will sit near the window.

You will wear a brown beret and the waiter

(who has already fallen in love with you)

will breathe a small sigh when he passes

your table. He will hold chairs

for the matrons in their absurd hats

but he will never take his eyes from you.

I will look out the window at the

ageing day and be happy for my Buchteln

And the white carafe that’s put in front of me.

I will not look at you: I will not say Fräulein

Have I mentioned that the way you sit

and the way you move your neck, has made

me certain that all the artists of Florence

were right about the mystery of women.

I hold the small cup to my face

to steal its warmth

and for a moment I close my eyes

to shut you in the warmth.

But you do not look up. Outside everything

is caught--people and shops--in a whit-grey mist

against a winter sky. But inside it is filled

with you. I imagine what it would be

to touch your shoulder in passing.

I know you have not turned a page

for half an hour. My cup is

down to the last drop and I must go.

I say Die Rechnung, bitte, and it is brought

but I have disturbed the waiter’s thought

of you and he somehow knows

that I am thinking only of you.

Not even a book or a newspaper to disguise me.

I will come again tomorrow, and you will wear red.

Published on January 12, 2015 01:47

January 6, 2015

The Fortunate Girl

do you know what you are

as when you sleep in a knot

or wake with your face struck

by a dream

or when your eyes

caress your face in a mirror

or the eyes of worshipers

envision you in your movements

like the promise of hot rain

lying straddled under a fan

or old women

who want to touch your hair

hissing their daughters

do not have such strong hair

do you know that you are

not what they see

not Helen nor yet Europa

some trophy for a boy or god

to rake and toss aside

no you are your voice

and the rhythm of your eyes thoughtful

and the terror in your face unloved

and the cry of your heart for another

and the beauty of a single flower

that will not come before I leave you

Published on January 06, 2015 02:07

December 28, 2014

Holy Atheism: The Puzzle of Heidegger’s “Letter on Humanism”

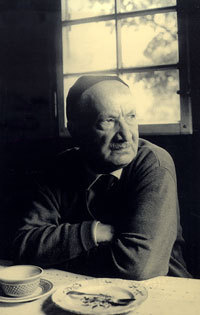

The origin of this little essay is a conversation I had a few nights ago when I was asked, quite unexpectedly, what books I might recommend to students seeking a deeper understanding of the world. Without much thinking, I pointed to Heidegger. Reflecting afterward, I realized that for most people Heidegger is merely “difficult” and that for many analytical philosophers (Ayer comes to mind) his writing is “rubbish.” In the right hands however, Heidegger can change minds and change lives.

Martin Heidegger is never an easy read, but he becomes more difficult with every new claim to offer a proprietary interpretation of his thought. In 1947 Heidegger published his Brief ueber den Humanismus (“Letter on Humanism”) in which he sorts through some of the tangles left behind in his 1927 opus, Being and Time and a treatise usually translated as What is Metaphysics? To come at this essay without some notion of Heidegger’s technical vocabulary, especially his complex views on metaphysics, is quickly to sink into linguistic mud. It’s equally difficult to sort through the later work without approaching it problematically. By that I mean that for all its emulsion, Heidegger was working through a very specific set of problems and a level of despair that has occasionally occupied philosophers to such an extent that paradox, aphorism and obscurity have seemed the only way to express the intractability of the problems themselves. Nietzsche comes immediately to mind, but there are tempting if imperfect analogies between Heidegger’s views and those of the negative theologians Gregory of Nyssa, Catherine of Sienna and Meister Eckhart.

The style he preferred in responding to his admirers—like Sartre–as well as his critics, such as Hannah Arendt—was never unconditionally generous, leaving the impression that Heidegger saw his particular mode of expression as appropriate to the subjects he tackled and most interpretation as being either reductionist, or erroneous.

He was not unaware of the power of double-speak as a tool in both political and philosophical discourse. In a 1966 Der Spiegel interview concerning his alleged Nazi sympathies (which finally cost him his teaching career and diminished his reputation in Germany), Heidegger said that in 1935 he had counted on the power of words to convey different meanings to two constituencies (his cleverest students and determined Nazi informants) when he praised the “inner truth and greatness of our movement.”

His sense of how words shape reality and can thus misshape perception and meaning is a constant prickle for anyone who wants to “interpret” Heidegger. It makes equally difficult the task of determining his influence on other thinkers, especially the French philosophers in whose eyes he found grace after 1967.

What makes the “Letter on Humanism” worth discussing is that he pulls no punches about his agenda: to locate in history the source of modernity’s ills. In the politically charged climate of postwar Europe, the easy answers focused on economic, religious, technological and social evils. The cure, it was often proposed, was to restore meaning to the term “humanism” as a category that rises above the particular expressions of modern culture.

In an important article, Gail Soffer notes that “What is peculiar to Heidegger and really questionable in his critique is his diagnosis of the cause of modernity’s ills: not capitalism and its greed; not Protestant religious beliefs; not even runaway technology or the Gestalt of the worker; but rather the humanism of the Western philosophical tradition. For Heidegger, “humanism lies at the root of the reification, technologization, and secularization characteristic of the modern world” (“Heidegger, Humanism and the Destruction of History,” Review of Metaphysics (49) 1996).

Heidegger was not, of course, unaware of the history of the term humanism in early Renaissance thought or even earlier glimmerings in Christian thinkers such as Abelard and Pico della Mirandola. But he was not especially interested in this history of discussion, or at least such discussion could only be useful in deconstruction (Destruktion).

In a strictly connative sense, humanism is that philosophy which either assigns a defined universal essence to man as “a rational animal,” characterized primarily by voluntary action, or it is the denial of essence—a position leading ultimately to Sartre’s conclusion that existentialism is a pure form of humanism. Man is what he is through choice and action. The political appeal of the latter position is that a non-essentialist view of humanism leaves open the possibility for human beings to create worthy social institutions, human rights, Bildung in the humanities and “true” sciences (as opposed to mere technological expertise), and also to reject unworthy ones—such as Nazism.

In none of his writings, however, does Heidegger suggest that “man has no essence.” His message in the “Letter” is that this essence has been misconstrued: that to say “Man is a rational animal” is to predetermine what the nature of man is at a metaphysical level, and that to do so shuts off discussion of the relationship between Being and being human.

To be a knowing subject in relation to known objects is, for Heidegger, to determine the essence of man “downward.” Out of a range of possible definitions, we have chosen the ones that equate science and reason with the sufficient definition—the essence—of humanity. In historical context, we have taken the historical determinants of humanism, which Heidegger sees as a set of familiar phenomena, as being the same as the underlying essence of these phenomena. Heidegger rejects the idea that humanism as we understand the term can provide an understanding of what it means to be thrown into a world of possibilities and others. It does not provide an “analytic” that can help us to understand authenticity, mortality, responsibility. Humanism can provide no escape from the “vulgarity of calculation” or a sense of the temporality of existence.

This leads to the question of God and the matter of Heidegger’s atheism. To an extent, we are playing with language in a way Heidegger would, approvingly, have found amusing. The a-theism he subscribes to is a rejection of God–literally being without the God of history and tradition–and a quest for a non-metaphysical God. It is this aspect of Heidegger’s thought and the subject of die Kehre or “turning” (biographical or procedural?) in his thinking about Dasein that frustrates interrogation—in spite of a small embarrassment of new sources published since his death.

In the world of poetry and technology, God remains the subliminal (literally, beneath the limit) problem. Theologians since Ebeling and Bultmann have exploited this aspect of Heidegger’s almost mystical argot on the topic, and Stuart Elden has analyzed the subject in a useful article (“To Say Nothing of God”, Heythrop Journal, 45/3, 2004, 344-48.). It has been frustrating to students of Heidegger that this “refusal of a theological voice” (Laurence Paul Hemming, 2002) tweaks the nose of theology rather than encourages theological speculation. But, as with humanism, any unconcealed definition of God would be trivialization, and it has been the role of historical theology to offer familiar formulas and definitions in place of concealment.

Thus Heidegger has theology precisely where he wants it: trying to figure him out. His challenge to humanism: that we cannot employ it to address questions of meaning, value and authenticity. His challenge to theology, that the discovery of God cannot be something as simple as forming objective images from subjective data, mainly historical. The possibility of a God without being must be considered. Aquinas considered it. But the axiom “There is no God” cannot be derived from the possibility.

Published on December 28, 2014 03:33

December 26, 2014

The Rābiʿah of Samarkand

And so I wait for something plush,

Something decisive beside the tomb

Of Timur’s wife. Before Taj Mahal

There was this mosque. Ninety five

Elephants, ten thousand precious stones

And the conquest of the world rest here.

Love Does this and quieter things:

It moves hearts to works of courage

And to deceit. I have yearned to see

The work of the heart in you,

Like this courage, like these lies,

Gratitude that cannot last

But leaves a glistening impression

On the mind and makes the heart

Burn with possibility. You are

Merely the gateway: I smell the spice-sellers

On you, hawking, and the worshipers unsure

Where to turn because of you, you are so much

I cannot see or know or say.

Here under the tiles Bibi Khanum lies dead and even

This magnificence could not save her reputation,

For the architect’s kiss was so hot

It left a burning scar upon her face, a wound

That even Tamburlaine in all his glory

Could not ignore or forgive.

Published on December 26, 2014 07:58

Khartoum

Khartoum is a site devoted to poetry, critical reviews, and the odd philosophical essay.

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

Khartoum is a site devoted to poetry, critical reviews, and the odd philosophical essay.

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

...more

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

Khartoum is a site devoted to poetry, critical reviews, and the odd philosophical essay.

For more topical and critical material, please visit https://rjosephhoffmann.wordpress.com/

...more

- R. Joseph Hoffmann's profile

- 48 followers