Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 313

March 10, 2012

The Numbers Game

I'm in the part of the book now where, at least for the first act, it's time to tighten and polish and get that truck draft out to the betas. Which means it's time to do word counts. (Note: all the numbers in this post are about my writing, reflecting my pacing, and aren't meant to be suggestions that other writers should follow. They're just here as illustrations. Don't get paranoid about numbers.)

I've talked before here about pacing, and about how acts should get shorter so that the reader senses the turning points coming closer together and feels the pace pick up. That means that in a 100,000 word book, the first act should be right around thirty to thirty three thousand words. Roughly. Much longer than that and the reader starts to get used to the story and loses interest. You need to throw in something that turns the plot in a new direction about a third of the way in, or the book dies. So the act ends on a turning point and you're off to the races again in Act Two and a brand new book. In theory.

Which means one of the duller things you have to do is analyze the word counts in your chapters, not because you're writing to a goal, but because the reader is reading your scenes and subconsciously gauging the pace of the story through scene event and length. An average scene for me is about two thousand to twenty-five hundred words. Big set-piece scenes might go longer because they're more complicated, but even then, too long and the reader starts to look at her watch.

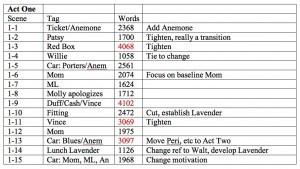

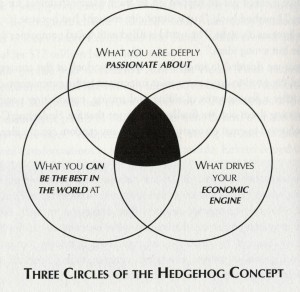

So I count the words in each scene. Well, the computer counts the words, but I keep track:

(If you click on the image, it will open up larger.)

That's fifteen scenes, which is a little short for me, but 34,974 words in the act. That's pretty good. I need to rewrite some of the scenes anyway, and I can always cut, so even if there are additions, I can get it between 30,000 and 33,000 easily. Once I had to get it down from 45,000 words. That was not a good day.

The key is to look at where I got wordy, and I have helpfully highlighted those counts in red: Scenes 1-3, 1-9, 1-11, 1-13.

1-3 is the Red Box scene, and four thousand words for that is ridiculous. It has to come down by a thousand at least. I'm trying to front-load the book with info and that never works. So even though I like that scene, a quarter of it is going to go, either to another part of the book or into the trash. The third scene in a book is a terrible, terrible place to do flabby structure.

1-9 is a set-piece scene, Liz in a bar waiting for Molly and talking with three men: Duff, Cash, and Vince, although Vince only has a line or two at the end since they pass in the door as she's leaving and he's coming in. I'll let a set-piece go longer because they do so much and the action is pretty fast, but not 4000 words. I'm just being self-indulgent there.

1-11 is back in the bar talking to Vince. I'm a romance writer at heart, so 3000 words of banter with the Good Guy is right down my alley, but I can tighten that, too.

1-13 is another set-piece, but I already know a chunk of that is moving to Act Two, so that's no problem.

But what about the scenes that are underfed? If a scene drops much below 1700, I start to look for what I didn't develop properly.

1-2 is right at 1700, but that's really a transition from 1-1 to 1-3 that sets up the pay-off in 1-3, so that one's okay.

1-4 is short, but it's also a transition, and it works as it is: nothing is undeveloped and it does the job it's supposed to do. I'm leaving it alone.

1-7 I'll look at again, but I think it's going to stand, too. There's a lot of tension in that scene and Liz wants to get out of it, so I'm okay with it being on the short side.

1-8 is another scene that's basically a transition; it really finishes off 1-7, and gives the reader a breather before she's thrown into the set-piece in 1-9, so I'm good with that.

1-14 is going to get a major rewrite. I knew it was coming, I knew I'd bobbled that scene, so this is no surprise. It's an important scene, it's the center of a three-scene sequence that ends with the act's turning point, and I phoned it in, thinking I'd get back to fix it later. Later is now.

Still, over all, I'm pretty happy with this word count. Fixing it is feasible. I'm probably okay here.

As long as Act Two is 25,000 to 30,000 words. And from where I'm sitting, it's looking looooong.

You know, some people just pace their stories naturally. They don't have to go through all this crap.

I aim for them when I drive.

March 7, 2012

What Does It All Mean? (Please, Please Let It Mean Something)

The good thing about naming scene sequences and acts is that it becomes a shortcut to what your story means. After my first drafts, I know what's in my story, and what the plot is about (This is a book about X who wants Y but can't get it because Z), but sometimes I can't see the shape of the plot and what that shape tells me about what the story means. Structure is meaning, always, if you change the structure, you change the meaning. So naming the parts of the structure should boil the meaning of the book down to its essence. If it has an essence. Please let this book have an essence, please, please, please . . .

So start with naming the acts, and you can't name them until you know what they're about so . . .

In Act One, Liz is stuck in her hometown, trying to get out, while people try to pull her back in to fix things.

In Act Two, Liz has agreed to stay for the weekend to help a friend, but she's leaving on Sunday.

In Act Three, there's been a murder and Liz is mad as hell about it and stays to find the killer.

In Act Four, the killer targets Liz and she's fighting for her life and by extension the town she tried to leave in Act One.

Yeah, it took me two years to get that. I'm old.

So . . .

Act One: I'm Not Going To Fix Anything Because I'm Gone

Act Two: I'll Help Out This One Time Because It Changes Things, But Then I'm Gone.

Act Three: I'm Not Letting Anybody Get Away With That

Act Four: You're Going Down, You Bastard

Uh, no. Negative goals. Let's try that again.

Act One: You Can Go Home Again, You Just Can't Leave

Act Two: Always a Maid of Honor, Never an Escapee

Act Three: Attention Must Be Paid

Act Four: Somebody's Out To Get Me And That Stops Now

Uh, no. Not related. One more time.

Act One: Walking Into Trouble

Act Two: Taking Control

Act Three: Fighting Back

Act Four: Defeating the Bad Guy

Nope. That could be any book. One more time:

Act One: Liz comes home and starts a revolution.

Act Two: Liz fixes things and pisses people off.

Act Three: Liz decides the last thing to fix before she leaves is to find the killer.

Act Four: Liz's last attempt at fixing something small becomes a life or death fight to fix something big.

I like that better, it's much more about Liz in action, and escalating, and they're all related, but they're descriptions, not titles. So:

Act One: Broken Home

Act Two: Home Improvement

Act Three: System Failure

Act Four: The Big Fix

Okay, those I like. They're about Liz doing things, they encapsule what happens in the acts, they're related, and they escalate. I can live with those.

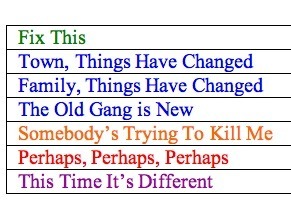

Which brings us to the scene sequence titles. In the first act, mine are:

There are really only four kinds of sequences, though.

The first, Fix This in green, is Liz falling back into her old habits of managing things, fixing other people's mistakes, saving people. It comes from both her basic personality and growing up the child of an alcoholic, so it's something she has to come to terms with. It's part of who she is, so it's part of her journey plot, and her attempts to fix things will also motivate a murderer. So the Fix This sequence pretty much propels the Journey plot, but Liz's actions also motivate the Murder plot, and they also establish a bond between her and Vince, the town cop, since they're both Fix It People, so they fuel the Romance Plot, too.

The second Things Have Changed in blue, is about the contrast between the way things were when Liz left home fifteen years ago and the way they are now in the Town, in her Family, and with her Friends. The Town and Family changes are going to motivate Liz to do things differently this time which is also going to motivate the murderer. The Friends changes are more subtle, mostly due to everybody not being teenagers any more, and more powerful because Liz can see what she had all along and where she's made her mistakes. So the Things Have Changed sequences are about the Journey plot, but they also motivate the Murder plot, and since Vince is one of the big changes in the Town, they also motivate the Romance Plot.

The third is Somebody's Trying To Kill Me and it's all about the Murder plot, but it also has an impact on the Journey plot (nothing makes you re-examine your life like a near-death experience) and provides motivation for the Romance Plot.

The fourth, Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps, is the Romance Plot, but the romance has a major impact on Liz's Journey and also complicates the Murder Plot (it's harder to kill somebody who hangs out with the cops).

The fifth, This Time It's Different, is really a turning point sequence, Liz's growing determination to fix things erupting in a big way, and since it's a turning point sequence, it affects all three major plots.

So what good does that do me? It sets up the sequences for the next three acts. I have to hit all of those or I've dropped plot arc. They don't have to be in the same order or have the same number of scenes, but I have to hit those titles in each act, in a way that reinforces the title/theme of each act. So I take the scenes I already have written and look at them to see where they fit, or come close to fitting, and then tweak them so that they're part of that scene sequence arc. I can pull out all of the scenes in those sequences across the book and check to make sure that I'm not spinning my wheels, that that list of sequences really does move. It makes the vast number of words in the book organizable, although it would be death to plot this way from the beginning. First the juice, then the glass.

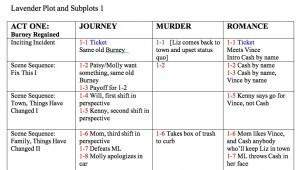

And then, of course, I move to to making sure the six subplots all serve those act and sequence titles while arcing.

So . . .

This book is about Liz who wants to fix what's wrong in her life and in her old home town but can't because there's a homicidal loon on the loose who likes things the way they are.

It's told in four acts:

Act One: Broken Home

Act Two: Home Improvement

Act Three: System Failure

Act Four: The Big Fix

divided into these scene sequences

(Click on the chart to enlarge; there are some blank entries under the Murder column to avoid spoilers, but there's stuff in there, trust me).

I definitely do not do this for every book I write (I'd be insane), but when I've got one that's been off the rails for two years, I do this. As soon as Lavender is finished, I'll do it for You Again because that one is also close to being done and off the rails. This just gives me a map to follow, a sense that I know what I'm doing.

And now, having hopelessly confused and depressed everybody, I'm going back to work.

March 5, 2012

Scene Sequences: Another Way To Make Yourself Crazy

So scene sequences are what's going to save my butt on this book, I think. Scene sequences are scenes in a sequence–go ahead and try to define "baked potato" beyond "a potato that has been baked"–and if you track the sequences you can see the shape of your story. Got it?

Okay, let's start again.

Scenes are units of conflict. They start where the trouble starts, escalate in tension, and end when the conflict is resolved and the characters are thrown into the next scene. And I do mean "thrown" as with great force. Okay, with escalating force. So the things you ask yourself about scenes is not just the old protagonist-goal-antagonist-conflict-crisis stuff, it's also, "Where does this scene throw the characters next?"

(I've been talking with Lani about doing a podcast/lecture thingy for Storywonk on scene structure, but the drawback is that you'd have to buy it. Is that a bad idea? I think they're about ten bucks.)

Where was I? Oh right, where do the characters land next? Sometimes in a related scene and sometimes some place completely different (although still attached to the story spine). Scenes that are related and happen one right after another are scene sequences. Each scene has to be considered a unit of its own, but the scene sequence also has a structure and a meaning of its own.

That's still confusing. So here's part of Liz's first act.

Scene 1-1 (first scene of first act) is Liz deciding not to stop in her home town after all and then getting picked up for speeding, after which she guns her ancient car too hard and it breaks down, forcing her to stay. It's the inciting incident in Liz's Journey Plot (refusal of call, anybody?) and while it throws her into the town and the story, it's not part of a scene sequence.

But then in Scene 1-2, she's at the garage that's going to fix her car which is run by a friend from her past who tries to convince her to stay and is then joined by her cousin who tries to convince her to stay. She says "No." Then in Scene 1-3, she goes to lunch with her cousin while waiting to find out about her car and finds out why they want her to stay. 1-2 sets up her suspicions and 1-3 pays them off. That's a scene sequence. The sequence ends because she says, "Hell, no," but the conflict lives on in other sequences.

To help me keep all these sequences together, I give them names. That one is Eloise. No, I kid. That one is "Fix This I" because that's what Liz did for her first eighteen years, fix everybody's problems, something she's determined not to fall into again. So she says no, loudly, when asked to fix something in this sequence. But in Scenes 1-16, 1-17, 1-18, and 1-19, she's again pressured to fix things. That sequence is "Fix This II," and she starts by saying "No" again and then is drawn in. There are "Fix This" sequences in all four acts that escalate in tension (one is a wedding from hell, one is a murder, and one is somebody trying to kill her), and if you pull the sequences out and just look at them by themselves, they arc from Liz saying, "No," to Liz fixing things again because people need her and that's what she does. It's a part of finding herself. I knew that was all part of the plot, I do plan this stuff sort of as I write the first drafts, but until I look at my rough draft and break down where the parts of the plot are, I can't be sure it's arcing.

The other sequences are "The Town, Things Have Changed I" (1-4 to 1-5), "Family, Things Have Changed I" (1-6 to 1-8), "The Old Gang Is New" (1-9 to 1-11), "Somebody's Trying To Kill Me I" (1-12 to 1-13), "Family, Things Have Changed II (1-14 to 1-15), "Fix This II (1-16 to 1-19), "Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps I" (1-20 to 1-22, the romance plot; I like Pink Martini, sue me), and "This Time It's Different I" ( 1-23 to 1-24) which always ends with the turning point scene. See? Clear as mud, right?

Okay try this: group related sequential scenes together and give them titles that identify the escalating central conflict in some way. Better?

Once I have the scene sequences figured out, I can look at all the Fix This sequences to make sure they escalate, that Liz is slowly drawn back into her old role. I can look at Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps and make sure that both the emotional and the physical arcs in that relationship are strong and clear. And I can look at the four "This Time It's Different" sequences and make sure that they escalate in intensity. It's another way of reducing a complex plot and 100,000 words to manageable units.

All those sequences have to be set up in the first act because introducing something new in later acts slows the book and confuses the reader. Even if a character arrives on the scene in a later act, he has to be mentioned and foreshadowed in the first act so that the reader has all the playing pieces in the game. (For example, if you've read Welcome to Temptation, you know Davy doesn't arrive until late in the book, but they talk about him all the way through the first two acts, so he's been introduced and is a presence on the page.) So once you have the scene sequences for the first act, you have them for all subsequent acts.

Then I have to make sure they all connect, not only in sequence with each other but across all the plots and subplots, but that's a different blog post. It's also why I need the tables to get the book from rough draft to truck draft. I know it sounds like I'm babbling, but once I have the rough draft done, this really helps me rewrite to pull all the parts together. Where the juice is in all of this is problematical, except that much like images in a collage, when I see the scenes in juxtaposition to each other, stuff happens in my head. But mostly, it just gives me the illusion I'm in control of the book.

One caveat: Don't do this before you write the first draft. Write the story off the top of your head and then use this kind of stuff to sort out the word salad you end up with. Otherwise, no juice at all.

And that should answer your questions about scene sequences. Oh, wait, nobody asked about scene sequences.

Never mind.

March 4, 2012

The Juice and the Glass On the Table in Word

I'm trying to figure out where I ran off the road with my writing. Lani and I talked about focus last night after watching Laura for PopD (podcast goes up Monday), discussing it first in the podcast where the screenwriters ran off the road with Laura, and then after the podcast was over, segueing into where I took a wrong turn. I told her when I started writing, it was all juice–excitement, flow, voices talking in my head–and no craft. Then I started studying craft and about ten years ago I hit the center of the bell curve, equal juice and craft. And since then, I've been losing juice and relying on craft, which is not a good thing. I said, "If you have to choose between luck and skill, pick luck; if you have to choose between juice and craft, pick juice. And I'm out of juice." Lani said that was crap, but she's wrong. Somewhere along the line, I got a juice leak and tried to plug it with really tight craft. I don't think it's working.

But here's the thing. Just juice can make for a really awful book, one that goes all over the place. I read an interview with three screenwriters once who were decrying the three-act-structure, saying that there were so many dull, conventional screenplays out there written by plugging story into the three act diagram. And my thought was, Yeah, but without the three-act structure you'd have had a conventional story that was all over the place. Craft is not the enemy. Craft doesn't kill juice. Craft shapes juice. It's the glass that holds the juice, transparent so you can see all the fruity goodness but hard and strong to hold in the stuff that would otherwise be making a sticky mess on the page.

I may have gone too far with that metaphor.

So I'm looking at the mass of words that is Lavender's Blue. I have at least a dozen different drafts of some scenes. Pieces of dialogue, fragments of action. Entire files labeled by act, many of them different drafts of the same act. I'd say I spilled the juice, but in fact, I never had it in a glass. I tried outlining a glass but it didn't work. I hate this metaphor. Where was I? Right, I had a word salad the size of the Grand Canyon. (Yes, I am on a restricted diet, why do you ask?)

So I've been spending the last week trying to sort things out. Gathering up every word I ever wrote about or for Lavender's Blue. Sorting them into files, getting rid of obvious duplicates, putting all fragments into a folder . . . bleah. And then I looked at my plots.

There's the main plot which should be the murder but because I took a left turn somewhere, it's a woman's fiction/women's journey plot. That's okay, Jen saw the first chunk of the novel two years ago and said, "Oh. This isn't what I thought it was going to be, but I like this, too. Go for it." I love my editor. So first, Liz's journey. But Liz's journey is really an emotional/internal plot, so I need an external plot, the kind where events happen and things blow up. (I miss writing with Bob; he did all the plotting.)

So the external plot is the murder mystery, which is difficult for me, but too bad, it's a mystery series and that's the main external plot.

Then there's the romance plot. It was going to be the main plot of the four-book series, each book an act, but it's not unspooling that way which is fine by me. It's a good subplot for the mystery and the women's journey, and that's all I care about.

You'd think that would be enough, but evidently at some point I decided I wanted to be Dickens, and there are six more.

There's the Mom plot: Liz is coming back home after fifteen years (she sees her mom once a year at Christmas) and there are things they need to talk about which they end up talking about because of the events of first three plots. But I still have to trace the arc of this plot separately to make sure I don't lose it, so it gets its own plotline analysis.

There's the Best Friend plot, also with unresolved issues that get resolved because of the main three plots. And again, it needs its own plot arc and analysis.

Then there's the Little Kid plot. This one wasn't supposed to be in there, but she showed up, and she's such a doppelganger for Liz as a kid, and their interactions change Liz, so yep, it needs an arc and an analysis.

And since Liz has a job, there's the Boss plot, the woman she's ghostwriting a memoir for keeps calling her, putting on the pressure. So she has to call, but as always, we need to get that bag a day job, so her calls have to change the story, which they do, which means they have to arc, which they do, and hello, another plot analysis.

And there's the dog. The dog kind of snuck in and looked at me with those eyes and then I realized what happened with it was integral to the main journey plot and even interacted with the other two, so I had to get a dog arc.

I thought that was it, but then I forgot there was an Old Nemesis, and he was going to have a major impact and character arc, so . . .

Yeah, nine plots and subplots. Then I listed all the scenes and numbered them and made a chart with the plots and subplots across the top and the scene sequence names along the side and filled in the first act for everybody, and then I thought about killing myself, but I kept working anyway, and as mind-numbing at all of that was, it showed me how all the plots formed the first act, which meant if I kept going it would show me the second, third, and fourth acts, and I looked at all the relationships and suddenly I had people talking in my head again. Juice, thanks to Craft.

So that's why it's been so long since there's been an Argh post. When I got to the point where I couldn't stand working any more, I made cookies or pincushions which are Re-Fab posts. All I could have done on Argh was weep helplessly, so that wasn't good. But I've stopped sniveling now, and tomorrow I'll take apart Act Two and Three and if I'm on a roll, Four, and then I'll print it all out and tape it up and stand back from it and see if I can see the shape of it.

But the POINT of this post is, you need both juice and craft. Thank you.

February 24, 2012

Deeper Than Lower Midnight

Generally, I don't think about oceans much. I'm more a river kind of gal. But TPM directed me to this BBC News graphic on the ocean, and just scrolling down the page made my heart beat faster. I will never again think of the Mariana Trench as just deep. It's deeper than Lower Midnight (there's a great book title). Go look at the graphic. It's amazing.

February 22, 2012

Good Site: Book Art

Thanks to Rox for this link to Brian Dettmer's gorgeous, gorgeous art from old books (click picture for full size):

February 21, 2012

Good to Great or Stuck to Moving

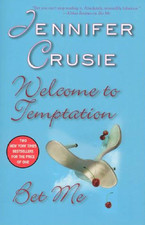

I have always been a big proponent of write what you need to write, not write to the market. I still am. But a recent comment on Lifehacker led me to a recent post on the Wandering Mirages blog, that led me to the Hedgehog Concept from Jim Collins's book, Good to Great. It reminds me of some of the tools in What Color Is Your Parachute, a book that helped me tremendously about twenty years ago in making some big life decisions. The Hedgehog Concept (not to be confused with the hedgehog song from Discworld) goes something like this:

1. What do you love? What fills you with joy when you do it?

2. What are you good at? Really, really good at?

3. What will pay you a living wage? (You define "living.")

The place where all of those intersect is where you should put your energies.

Or:

I still think that you have to write what you have to write, but if you're looking at changes in your life that are affecting your decisions about what to write or just your ability to write certain things, I think this is really useful because it simples things up: here are the three basic things you need to know about yourself. Now what do they mean to you?

February 19, 2012

Lost in Translation: First to Third and Back Again

Lots of commenters on the previous post said, "Write it in third and then change it back to first." That doesn't work for me (I've tried), which doesn't mean it won't work for you. But for me, it's two different languages. It's like saying, "Write it in English, and then translate it into German, and then translate that back into English." If you're talking about a page full of dialogue, it doesn't matter much, but for anything else, I lose a lot in the translation both ways.

Here's a piece from Maybe This Time:

Andie looked around the room and saw ancient heavy furniture and a bed covered with old blankets in various shades of drab. The only interesting things in the whole room were the stacks of comic books, papers, and pencils on the bedside tables that said Carter did something besides glare and eat, and the carpet at the end of the bed that was riddled with scorch marks. Pyro, she thought, and was grateful the house was mostly stone. She looked up to see Carter watching her, his face stolid, so she nodded and began to close the door only to stop when she took a second look at his bedside table.

That's third person limited, in Andie's point of view; it's deep in her head, but even so there's some distance there. Now here it is put into first person by changing only the pronouns:

I looked around the room and saw ancient heavy furniture and a bed covered with old blankets in various shades of drab. The only interesting things in the whole room were the stacks of comic books, papers, and pencils on the bedside tables that said Carter did something besides glare and eat, and the carpet at the end of the bed that was riddled with scorch marks. Pyro, I thought, and was grateful the house was mostly stone. I looked up to see Carter watching me, his face stolid, so I nodded and began to close the door only to stop when I took a second look at his bedside table.

Andie comes across cold here, just reporting what she sees, with a couple of snarky references. If somebody is actually telling you things, there has to be more personality there, more immediate emotional response, unless the character is one of those just-the-facts-ma'am guys:

I looked around the room and saw heavy furniture that was older than God and a bed covered with blankets that were older than Mrs. Crumb. But there were stacks of comic books, papers, and pencils on the bedside tables, so Carter did something besides glare and eat, which was cheering. Then I noticed that the carpet at the end of the bed was full of blackened holes. So the kid really was a pyro. Fabulous. Thank God the house was mostly stone. I looked up to see Carter watching me, no expression on his face at all, so I nodded, trying to look cheerful and supportive, and began to close the door only to stop when I saw what else was on his bedside table.

If you're in first person, you're not in narrator voice, telling what's going on deep inside Andie's head, you're Andie, giving a running impression of what she's seeing and feeling. The voice, the outlook is completely different.

So why not write it that way in third person? Take the first person and put it back into third:

She looked around the room and saw heavy furniture that was older than God and a bed covered with blankets that were older than Mrs. Crumb. But there were stacks of comic books, papers, and pencils on the bedside tables, so Carter did something besides glare and eat, which was cheering. Then she noticed that the carpet at the end of the bed was full of blackened holes. So the kid really is a pyro, she thought. Fabulous. Thank God the house is mostly stone. She looked up to see Carter watching her, no expression on his face at all, so she nodded, trying to look cheerful and supportive, and began to close the door only to stop when she saw what else was on his bedside table.

The change from first back to third works better than the others, but it's too frenetic. If you're writing an entire book in third person, that intense, colloquial voice gets tiring because you never get any distance. Plus, there's just too much stuff in that paragraph, seventeen more words than the original third person paragraph that did exactly the same thing. First person needs more words because of all the stuff that people think; third person can elide right through that.

So let's go the other way. Here's a first person piece from Lavender's Blue:

I saw the Welcome to Burney sign around two o'clock one bright April afternoon when the air was crisp with the scent of rain that might turn to snow (spring in Ohio is iffy). You only have to stay for an hour or two, I promised myself, but right before the turn-off to my mother's street, I felt that old clutch in my stomach that said, Get out of here. My mother's a lovely woman—well, okay, no, she's not, but she's not a beast, that's my aunt ML—but life had been nothing but bad for me in Burney and nothing but good since I'd left, and Terri Clark was singing "Bigger Windows" from my iPod speakers egging me to keep on going to Chicago, so I floored the Camry, running from my home town like the rat I was. The old car coughed a little because it does not like being floored, but it was hurtling along like a champ when I heard the siren. I looked in the rear view mirror, decided that of course the cop had to be after me, and pulled over onto the muddy edge of the two-lane highway.

And here it is again, in third with just the pronouns changed:

Liz saw the Welcome to Burney sign around two o'clock one bright April afternoon when the air was crisp with the scent of rain that might turn to snow (spring in Ohio is iffy). You only have to stay for an hour or two, she promised herself, but right before the turn-off to her mother's street, she felt that old clutch in her stomach that said, Get out of here. Her mother was a lovely woman—well, okay, no, she wasn't, but she wasn't a beast, that's was Liz's aunt ML—but life had been nothing but bad for Liz in Burney and nothing but good since she'd left, and Terri Clark was singing "Bigger Windows" from her iPod speakers egging her to keep on going to Chicago, so she floored the Camry, running from her home town like the rat she was. The old car coughed a little because it did not like being floored, but it was hurtling along like a champ when she heard the siren. She looked in the rear view mirror, decided that of course the cop had to be after her, and pulled over onto the muddy edge of the two-lane highway.

That paragraph doesn't even make sense in third person as it's written. Who's making comments about Ohio weather and Liz's mom? That becomes authorial intrusion and moves the third limited POV close to third omniscient which is fine if you want a narrator's voice to dominate (see anything by Terry Pratchett for an excellent example of this), but if you want the voice to be Liz, then it has to belong to Liz, it has to be put into thoughts–My mother's a lovely woman, Liz thought, well, okay, no, she's not, but she's not a beast, that's my aunt ML—and they don't fit in the immediacy of that situation. She would not think that then. So you cut out everything that's not authorial intrusion and you get this:

Liz saw the Welcome to Burney sign around two o'clock one April afternoon. You only have to stay for an hour or two, she promised herself, but right before the turn-off to her mother's street, she felt that old clutch in her stomach that said, Get out of here, so she floored the Camry and raced past the turn-off. The old car coughed a little because it did not like being floored, but it was hurtling along like a champ when she heard the siren. She looked in the rear view mirror, decided that of course the cop had to be after her, and pulled over onto the muddy edge of the two-lane highway.

That's perfectly good third person, but you lose all of Liz's commentary. For me that's always been a good trade-off–I'd rather have short and clean than long and chatty–but not for this book. This book is about Liz going home and revising everything she thought she knew, so it's felt right to do it in first person all along. I really do like third better, I think it's sharper and cleaner and easier to read and gives the reader a lot more white space to collaborate in, plus shorter: the original first person paragraph was 195 words; the last third person version was 115. It took me eighty more words to write that in Liz's first person POV; for me that's the writing equivalent of eating a dozen Krispy Kremes: I'm a little sick afterwards and feel the need to get rid of some of it.

Then try to put that back into first person:

I saw the Welcome to Burney sign around two o'clock one April afternoon. You only have to stay for an hour or two, I promised myself, but right before the turn-off to her mother's street, I felt that old clutch in her stomach that said, Get out of here, so I floored the Camry and raced past the turn-off. The old car coughed a little because it did not like being floored, but it was hurtling along like a champ when I heard the siren. I looked in the rear view mirror, decided that of course the cop had to be after her, and pulled over onto the muddy edge of the two-lane highway.

Again, first to third works, it's clean, but it's flat. If Liz is that just-the-facts heroine, it's fine, but if she has a lively inner voice and an opinion on things, she's just not on the page.

Which brings us to the non-sex scene I put up. It's basically that last paragraph: flat impersonal summary. Putting it into third person won't help fix it because I wrote it in third person with first person pronouns, subconsciously trying to get that distance back. What I have to do is junk that entirely, stop being a wuss, and write it in first person this time. Point of view is not pronouns alone, it's voice and distance and worldview. I always knew that, but knowing something in the abstract and remembering it when you write are two different things. So I owe you all for making me think about this. Argh People to the rescue once again. Thank you.

February 17, 2012

First Person Sex: A Discussion

So I'm writing a book in first person and that's fun although different–only one POV, for starters–and then I get to the first sex scene. Hmmmm.

Here's the thing about first person for me: it feels like I'm sitting next to somebody on the bus and telling them a story. Okay, that's fine. But then I get to the sex scene, and even if it was Lani and Krissie on the bus, I wouldn't go into detail, not the kind of detail I use in third person sex scenes. It just feels wrong, not morally wrong (we crossed that bridge long ago), but out of place. My Girl Liz would not do that. For one thing, it'd be a betrayal of her lover ("So here's what he did last night . . ."). For another thing, it would probably make whoever was listening uncomfortable in real life. (TMI.)

I know fiction isn't real life, I know first person is a construct, but I'm having a heck of a time. I showed Lani and Krissie the first sex scene awhile back and there were crickets. Then Krissie said, "More dick and awe," and I said, "It's first person," and she said, "I write first person sex all the time," and of course she does, but I'm more repressed than she is. Well, everybody's more repressed than she is. But even no-sex-in-the-courtyard Lani said, "That's a little . . . distant." Or words to that effect. Okay, here's actually what they said:

Jenny: Okay, here's how bad I am at writing first person sex scenes. After Liz says she doesn't like guys who don't pay attention in bed she says:

Vince was not one of those guys. Vince wanted participation. Vince encouraged volunteering. Vince practically had a sign-up sheet, but that's okay because that's what I prefer. It all worked out just fine since anything he nudged me toward I was all for and anything I asked for he followed through on with what I'd call enthusiasm if it wasn't Vince. There were a couple of surprises along the way that upped the ante and a good solid climax for me and, I'm reasonably sure, for him. He didn't complain anyway.

That's the first sex scene. I'm screwed. FIRST PERSON. ARRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRGH.

Krissie: LOL. I'd put up my first person sex scenes but they're pages long.

Lani: It's tough writing sex in first person. But that's your first sex scene. That's their first sexual encounter, and sometimes, you're not terribly romantic about it.

Jenny: I'm afraid of sounding like that person on the bus who Shares Too Much. Liz isn't romantic at all. But I like Vince in that part. That's my kind of hero.

Krissie (typing at the same time): That sounds like the sex scene written by a man. Well, there it is. I still think she might have a reluctant reaction to all that. Not so cut and dried.

Lani: It's a first-person story. They want you to share. By buying the book, the reader's saying, "So TELL ME." And you're just doing as asked.

Jenny: uhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh. Don't make me.

Lani: I think it's consistent with Liz's personality, and it's fun. When the sex is important, and moving, she'll talk about it differently. And it doesn't have to be all hot-sexy. It's a mystery. There are dead bodies. Liz has shit to DO.

Krissie: You did a great job with that in Dogs and Goddesses. After we trained you for more shock and awe. Or was it cock and awe?

Jenny: Dick and awe, I believe. But that wasn't first person. First person is different.

Krissie: Yes, first person is very different.

Lani: In first-person, you have to be consistent with what the character would actually say. I think that's consistent.

Jenny

Well, I need to show the relationship arcing. Liz is not a needy kind of woman. She's responsible for her own orgasm.

Krissie: It can definitely be done. And despite what you say, you write really really good sex scenes. And I'm a connosseur — can't spell that word.

Lani: You do write really great sex scenes. But this is different. It's Liz talking about sex.

Krissie: Yeah, but I do first person sex scenes.

Jenny: I'll have to get drunk to write real first person sex in real time.

Lani: I think it's good. You're not writing a sex scene, you're writing Liz talking about sex.

Krissie: Did you know they let me get away with an inn in the Rohan books called The Cock and Swallow? heh heh heh.

Jenny: LOLOL!

Lani: The Cock and Swallow!

Jenny: Only in a Stuart.

Krissie:

My editor didn't notice until it was too late.

Jenny LOL again. I'm dying here.

Lani: Your editor didn't see it?

Jenny: I know. Cracks me up. Who could have missed that?

Krissie: So back to Liz. If sex to Liz was like brushing her teeth then it wouldn't be interesting.

Lani: Well, you write a different kind of story. You're not writing Liz. It's about how that character would talk about sex, and your characters would absolutely talk about sex that way. Liz wouldn't.

Krissie: And really, the sex needs to be interesting if it happens. She may be hard-boiled and matter of fact but something must have reluctantly touched her. No, that not "thing"

Jenny: That's another reason to summarize it. The real reason I wrote that was to characterize Vince. Liz is very practical about sex. But she's in a place that makes her vulnerable, and when she reaches out for somebody later, she reaches out for Vince. And it's different. But still in summary. I think the reader already knows who Liz is, but this is another look at Vince.

Lani: See, this is the first sexual encounter, and Liz isn't romantic. Later on, she'll talk about it with a bit more gusto, but right now, she's not allowing herself to be vulnerable to Vince. I think it's good for a first time. It'll be a while before Liz gets more into it.

Krissie: You just need a hint. Like you did in the original shock and awe scene. Which you turned into the terrific sex in the rain on the hood of a car. Richie was impressed.

Jenny: LOL.

Lani: I think it works. I think if you change it, you change Liz. It's absolutely who Liz is.

Jenny: It's who Vince is. That's why I needed it in there. It characterizes the hero.

Krissie: Well, if this is a throwaway at this point, and doesn't change her and/or him, then it's okay to summarize.But then, shouldn't every scene change the characters a tiny bit?

Jenny: Yes, it should. That's a good point, I'll have to make that clearer. This establishes the baseline for their sexual arc. Everything worked fine, they shook hands and went their separate ways, but yeah, it should change the characters at least a little bit. I think sex is a huge characterization . . . I want to say tool, but Krissie will run with that.

Krissie: LOL. Okay, that I'll buy.

Lani: Krissie will run with everything. And yes, as a starting place for the sexual arc, I think it's great.

Krissie: Any tool I can get.

So here's my question: What do you think about sex in fiction in first person? (Notice how carefully that is worded, please. I don't want to hear about the first person you had sex with. Well, I do, but not here.) How much is too much, how much is not enough, do you even want sex in a first person story? Because I've got three of those scenes in this book, and I'm going to have to get drunk to do them unless you give me an out.

February 14, 2012

Happy Valentine's Day!

Happy Valentine's Day to Argh Nation. Have some of that violently-colored Valentine's candy for me since I can't. (Love those cinnamon hearts.) And here's something interesting: Mollie just discovered that the Welcome to Temptation and Bet Me e-books are currently bundled for one low price of $6.99, which makes them about $3.50 each which the very-long-runnng poll to the right says is a reasonable price for an e-book.

Crusie on the cheap, available at Barnes & Noble, Kobo, iTunes, Android Market, the Sony eBookstore, and Amazon.