Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 265

July 19, 2014

Cherry Saturday 7-19-14

Today is National Raspberry Cake Day. If you make strawberry cake or key lime pie, Martha Stewart comes to your house and kicks your dog. (Serioulsy, Raspberry Cake Day? Who thinks of these things? I’m going to start making them up if the real ones don’t start getting better.)

July 12, 2014

Cherry Saturday 7-12-14

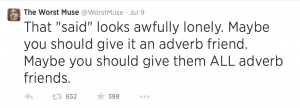

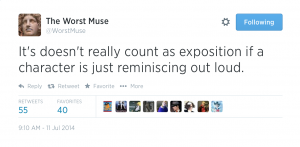

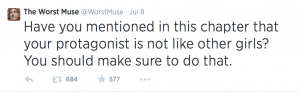

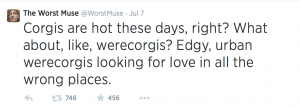

Today is Pecan Pie Day, but enough about that. Have you been reading The Worst Muse on Twitter? Because you should. It’s terrible and wonderful at the same time:

Sadly, there are probably people reading that feed and thinking, “Great advice.” Although actually the were-corgis idea might be a winner . . .

July 11, 2014

Leverage Sunday: Splitting Up Is Hard To Do

As I think I’ve mentioned before, I’ve figured out why the last season of Leverage is my least favorite even though it has wonderful episodes: Each story moved the team closer to splitting up. As a writer, I applaud this. After four years, the team members are not just masters at what they do but tightly bonded in a family that nothing can destroy. Which means there’s no place else to go unless they find a way to destroy that invincible family. Thankfully, they didn’t do that, but they did change the community, moving toward Nate and Sophie’s marriage and retirement from the con and the new Leverage International headed by, of all people, Parker, ably supported by Eliot and Hardison. It was absolutely the right thing to do narratively and creatively, but it took away the thing I loved best about Leverage: that family of five working together. I’m not complaining, I don’t see any other way they could have gone in a fifth season, and I would have said, “Hell, yes,” to a sixth season, but still . . .

Three of the season five episodes really sell the coming split: “The Broken Wing Job,” “The Rundown Job,” and “The Frame-Up Job.”

In “The Broken Wing Job,” Parker’s been left alone minding the pub because she’s torn something in her leg that’s immobilized her. The best way to watch this episode is to probably go back and watch “The Juror #6 Job” first. Parker’s arc is extraordinary and, in the context of the show, completely believable. Her family has spent four and half seasons teaching her to pay attention to things besides her thefts and to connect to people, and it all pays off in “The Broken Wing” because Parker not only spots thieves by paying attention, she connects to several different people in the restaurant and understands what they’re doing, too, even though they’re not criminals. Not only that, she solves everything, even the romantic entanglements, while foiling kidnappers. She does call Eliot and Hardison for advice, but when she calls Nate, he tells her she can do it by herself and hangs up, throwing her out into cold where she does just fine, redeeming himself when he comes home by quietly telling her that she did great work, just as he knew she would. It’s a father/daughter moment that’s brief but true, and sets up the next episode.

In “The Rundown Job,” Eliot, Parker, and Hardison are in DC for a diamond heist (for a good cause, of course) when they’re drawn into a domestic terrorist plot. Nate and Sophie have stayed in Portland, so it’s just the three younger team members, planning their own counter-terrorist moves, relying on each other’s strengths and trusting each other completely. Hardison figures out what’s going on, Eliot takes down the bad guy while taking a bullet, but Parker is the one who saves the day, neutralizing the biological weapon by being smart, active, and brave because if she doesn’t, people will die, something she’d never have done in the pilot episode. It’s a great episode, more action-oriented and fast-paced than usual, underscoring their less deliberate approach now that Nate’s not planning their every move in advance. (Also Adam Baldwin’s in this one, always a plus.)

Meanwhile, back in Portland in “The Frame-Up Job,” things are moving at a more adult, mannered pace. Sophie ducks Nate to go to an art auction that has a painting from her past, and of course Nate finds her anyway, he’ll always find Sophie, and that’s a good thing because Sterling arrests her for art theft. It’s a light-hearted Thin Man homage, with Sophie and Nate bantering non-stop, a rich old victim, battling noir relatives and employees, and Sterling being Sterling, all of which means it’s a lot of fun, a complete 180 from “The Rundown Job.” But it’s also there to show their future. They are rock solid as a couple now, married in everything but name, relaxed with each other even when they’re arguing.

What’s notable about “Rundown” and “Frame-Up” is that the two halves of the team don’t call each other for help. Parker touches base with each team member but Sophie in “Broken Wing,” but in these two episodes, each half of the team works completely independent of the other. Nate and Sophie have taken their criminal partnership to a new level of life partnership, and Parker, Hardison, and Eliot are now fully functioning, fairly mentally sound adults who work as a well-oiled machine, capable of handling anything on their own because they’ve learned to see the big picture (masterminds) and to pull cons (grifters), taking over Nate and Sophie’s roles and demonstrating that they’ll do just fine on their own as a team. Even in the context of team-as-family the split works: Nate and Sophie are ready to be empty nesters, and the kids have grown up and are finding their own way.

So intellectually, I understand why the community has to split. It’s just emotionally that I resist the natural evolution because I so love that Leverage team. And that may be the Kryptonite of team building: the community has to evolve or stagnate, and when the evolution reaches its point of most stability, the story is over. I’d still watch seasons six, seven, eight, through twenty-four of Leverage if they brought it back, but I can recognize that the writers left the series in a good place at a good time. The next episodes before the finale seem weak to me, not because they’re badly plotted, but because the team is too damn strong. They’ve become superheroes, invincible, so all the tension is gone. It really was time to split the team.

Which brings us to the question of when a story or a series is done. Life on Mars has sixteen episodes, way too few, and yet it ended where it was supposed to end, one of the many reasons it’s superb. Other shows keep going because they’re making money and then degenerate into blandness, tarnishing their early seasons’ shine. I still see Season Five of Leverage as an epilogue after the fantastic “Last Dam Job” showed the team finally bonded and secure. But I also love the way they arced the team into two parts while leaving them a family, and I’d love to see shows about Leverage International, the new team with new problems to work out. I really would have liked another season. Or four.

Just give me back that community, please.

July 10, 2014

What You Will Be Watching July 30

Guardians of the Galaxy won’t be out until August 1, but on the 30th of July, you’ll need a lot of popcorn for this . . .

Sharknado 2: The Second One.

July 9, 2014

Passwords To Remember

I recently changed all my passwords because of that damn Heartbleed thing, and I’ve been lost ever since. I knew all my passwords before because I’d had them for over a decade (that’s a bad thing), but finding secure new ones that I could remember turned into a nightmare. Then I found this post on Lifehacker that had this excellent password generator from security expert Bruce Schneier. Here’s my version of the Schneier method:

1. Pick a quote or a sentence that’s easy for you to remember.

2. Break it down into only the first letters of the words. (Use a sentence that has at least twelve words.)

3. Replace some of the letters with numbers and symbols (i = 1, o =0, a = @, s = $, etc.) and capitalize the first letter and any proper nouns (to make it easy to remember which letters you capitalized). Since it’s a quote, make sure you put quotation marks around it.

4. Take your password to a password checker to see its strength (the linked checker tells you how long it would take different kinds of hacking to crack your password).

5. If the password is strong, open a new doc and see if you can type that password from memory.

6. Profit.

So, for example:

1. “Blue canary in the outlet by the light switch who watches over you.”

2. Bcitobtlswwoy

3. Bc1t0btl$ww0y

4. It gets an 84% strength rating and would take a medium sized bonnet 173,000 years to crack that. BUT if I put quotation marks around it, it goes up to 99%.

5. Bonus: I get to sing “Birdhouse in my Soul” every time I sign on to Amazon. (Kidding. Not my password for anything because I’m not dumb as a rock.)

Of course, it doesn’t have to be a quotation, it just has to be a sentence you remember. “Veronica peed on Mona’s head, so please don’t pet the yellow fur” works, too. Vp0Mh$pdptyf gets a 77%/2000-years-to-crack-on-a-botnet rating; with quotation marks it goes to 91% and two billion years. (One thing to remember: if you make a document labeled “Passwords” and put your password into it, you’ve just shot yourself in the internet foot.)

Coming soon-ish: the rest of the Leverage posts, more questionables, and some ruminations on writing and critiquing. Probably.

July 5, 2014

Cherry Saturday 7-5-14

Today is Workaholics Day, which means if you’re working today, this day is for you, especially since it’s Saturday, which frankly, is just ostentatious of you. We’re not impressed. Go find a hammock and a good book.

July 3, 2014

Questionable: Sex in Stories

Deb Blake asked:

Sex. I have to put the occasional sex scene in my books, and it is SO hard to write sex scenes (or seduction, or even just attraction) well. Your sex scenes are among the few I actually like to read. Any suggestions?

Sex scenes are about sex the way dinner scenes are about dinner, which is to say, not. Sex is the action the characters are doing, but it’s not what the scene is about. Instead, it illustrates what the scene is about. If the characters have sex and it’s fabulous and there are no problems and they’re the same people at the end of the scene that they are at the beginning, then you can just write “And then they had great sex” and skip writing the scene because it doesn’t move story. But if something happens during the sex scene to change character and move story, then you have to write the scene, but you have to write the action of the scene (that would be the sex) in a way that shows character change and story arc.

The biggest mistake people make in writing sex scenes in books that aren’t erotica is writing the sex. Anybody who reads your book has either had sex or seen it on cable TV, so there’s no need to provide instructions. Your reader knows where everything goes. Your characters are likely not describing the action to themselves, and in fact as things heat up, they’re likely to become non-verbal. So what does that leave you? The things that are different, the actions that change things, the details that make those changes vivid. A sex scene is like every other scene in that it’s part of the story that the reader wants to live vicariously, in the same way she wants to vicariously flirt with the love interest and vicariously defeat that bastard antagonist. So you concentrate on emotion and sensation, putting her in the scene so that she can feel what’s happening, as the events change the characters.

This is one of the reasons that I love writing bad sex. It’s so much more interesting than good sex and it gives you so much more room to arc character and relationship. I think that problems that occur are a lot more interesting because then the characters have to solve them, right there, and the way they solve them characterizes them, shows them things about each other, and deepens the relationship. Anything that makes sex more difficult heightens tension: how do they handle people walking in on them, not being able to find privacy, wanting different things, misunderstanding what each other wants, their respective hang-ups and fears? That’s the stuff that makes scenes with sex interesting, arcs characters, and moves plot.

Don’t write sex scenes. Write fascinating scenes full of conflict that changes character and advances story shown through the sexual actions of the characters. Once you stop thinking “sex” and think “character and conflict,” it becomes a lot easier.

July 2, 2014

Questionable: 10 Things to Know About Publishing

Julie wrote:

How about . . . [a] Top 10 things nobody tells you about getting your book published, Top 10 things newbie authors need to know, middle-of-the-road/almost published authors should know…

Publishing is chaotic and ever-changing so any advice I give is subjective and possibly useless. Actually, any advice anybody gives is subjective and possibly useless. One thing to keep in mind when evaluating publishing advice is, “Does this make sense?” Because most of the time, it doesn’t. Here are some of the things my McDaniel students had heard about publishing:

Publishing Fact: “They’re not buying any authors over forty.”

Reality Check: Somebody shows up with a great book, but she’s fifty-one, so they decide not to publish her? Really? The current top ten authors on the NYT fiction list range in age from 44 to 71. Clearly, it’s an author demographic that still sells.

Publishing Fact: “They’re not buying new authors any more, they’re just publishing established names.”

Reality Check: That was so absurd, that I told my editor, Jen Enderlin, about it. She said, “YES! Spread that rumor so I can get all the new authors!” Discovering a great new author is the wet dream of every agent and editor because a great new author is the best way to build a reputation, not to mention a career.

Publishing Fact: “Historicals are dead.”

Reality Check: Historical fiction has been around for a couple of hundred years and historical romance has been selling steadily for at least a hundred years. What are the chances the twenty-first century killed it?

If you look closely at these facts, you’ll see they’re all useful for explaining why somebody’s book didn’t sell. “It wasn’t that my book was bad, it was that editors aren’t buying [fill in the kind of book she writes].” Generally speaking, any wisdom that says that X won’t sell or editors aren’t buying X doesn’t pass the logic test. Yes, vampires have been overworked, but if your vampire novel is so fabulous that the editor can’t resist it, she’ll publish it. No subject ever dies in publishing, although some of them take long naps, in which case one great book can wake them up again. (My fave bit of publishing wisdom: “Vampires are dead.” Yeah, but those suckers always rise again . . .) (Actually, the latest publishing fact I’ve heard is “Zombies are dead.” The jokes just write themselves, folks.)

But you wanted “the top ten things nobody ever tells you about publishing.” That’s impossible because people are always telling you things about publishing so everything has been said somewhere. But here are the top ten things that I, subjectively, would tell you about publishing, that may or may not apply to your situation, and that may or may not be true tomorrow. They’re in no particular order of importance until the last two.

1. Publishing is a slow.

If you’re talking about print, it takes a year. If you’re talking about a well-published e-book, it still takes about a year. That’s because publishing is not printing; that is, publishing involves marketing strategies, arranging placement in stores, devising public relations campaigns, and many other things that make the difference between your book dying on the shelf (real or virtual) and lots of people hearing about the book and being tempted to read it. One of the biggest misconceptions that e-publishing has given us is that you can write a book on Tuesday and publish it on Wednesday. You can write a book on Tuesday and make it available for purchase on Wednesday, and technically that is published, but since “publish” means “to make public” you could also publish it by leaving a stack of copies of the manuscript by your front door, and you’ll probably get about the same number of readers. It takes time to publish a novel well.

2. Publishing is a very small world.

If you’re standing on the outside, Publishing is huge and powerful. Once you’re on the inside, Publishing is a very small town. People have lunch, go to cocktail parties, call each other to gossip like crazy, and, most of all, know each other. There’s a perception that the rise of e-publishing has decentralized that small town and that it’s now spread throughout the country, but the heart of publishing is still NYC. Be professional with everybody, even the dickheads; you do not want to be a LITS author (“Life Is Too Short to work with this bitch again.”)

3. Publishing is populated by people who love books.

I’ve never had an editor or an agent who didn’t love books. Every editor and agent I’ve met has loved story, loved reading, loved making books that bring great stories to readers. They make lousy money and work incredibly long hours and when they do get time off, they read for pleasure, and most of them wouldn’t dream of leaving publishing because they just freaking love books. They really want to love your book, too. They are not the enemy.

4. Publishing is fluid.

Whatever I tell you now may not be true tomorrow. Hell, it may not be true by this afternoon. Everything in the world is changing right now, so it’s no surprise that publishing is in flux, too, but it’s even more chaotic because of e-publishing (a good thing) and the dying off of bricks and mortar stores (a bad thing) and the hacking away at the already slim profit margin by Amazon, a retailer who has also become a publisher (another bad thing). Publishing changes every damn day, so stay fluid with it.

5. Publishing is irrelevant until you’ve finished a book.

If you’re a first-time author, you’re going to have to have a finished book to sell, so researching (or worrying about) publishing before your book is done is a waste of time. Finish your manuscript and then while you’re in rewrites, do your research.

6. Publishing requires a good agent.

I know, it’s hard getting a good agent. It’s hard knowing who a good agent is. But it’s a nightmare trying to navigate publishing without one. The contracts are Byzantine, the procedures complex, the demands on authors constant. An agent stands between you and all of that. Because you have an agent, you will never have to talk money with your editor, will never have to tell the head of internet marketing that if he wants you to tweet every day you expect him to write your books, will never have to wonder what the hell a reversion of rights clause is and why the wording on it is crucial in e-book sales.

How to find a good agent: Finish your book. Then look at all the books you love that were published in the last two years. Find out who those authors’ agents were because they clearly have the same taste in fiction that you do. Research those agents (search for videos of panel discussions so you can hear them talk, google for online posts by them, find them on Facebook and Twitter, etc.). See if they feel right for you, if your personalities are compatible. Then put together a great proposal for your finished book and query them, mentioning the things that drew you to them and explaining in one short paragraph why your book is fabulous. That process takes a awhile, but the goal isn’t to find any agent fast, it’s to find an agent who loves your work with whom you can work comfortably for many years.

7. Publishing changes your life.

It won’t necessarily make your life better, it may make your life worse, but it’s definitely going to change it. If you have a friend who thought the two of you were just alike and you get published, you may lose that friend because she now feels like a failure, even if you’re lovely to her, even if she’s not writing a book. If you’re married, your significant other may feel threatened. Threatened people often turn to denigration: “Yeah, she wrote a book but it was just a romance.” “Yeah, she wrote a book, but it sold like twelve copies.” If you’re hoping for any kind of sales at all, you’ll have to become more public, working social media, making appearances wherever you can arrange them, talking about yourself and your work. Even your writing life changes; before you were hoping to get published, now you have a contract and a deadline and expectations and people who are going to judge this book by comparing it to your last book even if they’re completely different. And then there’s the IRS and the wonderful world of the self-employed. Getting published doesn’t solve anything, it just delivers a new set of problems challenges.

8. Publishing can eat your life.

Publishing is demanding. You’ll end up spending all your free time writing, marketing on social media, writing, going to conferences, writing, dealing with the business issues of being self-employed, writing . . . It’s difficult for the very few people who can afford to write full time, it’s really difficult for the people who are holding down full time jobs, it’s damn near impossible for people with full time jobs and children under fifteen, and frankly I don’t know how people who self-publish well are still alive because I don’t see when they sleep. Which is why it’s really important to establish boundaries for your career, say “this much time and no more will be spent on publishing” because otherwise everything else can get lost.

9. The key to surviving publishing is identifying and listening to your signal.

Separating the signal from the noise in publishing means separating what you want from your life and your publishing career from all the crap that people tell you about publishing. The mistake most people make when they approach publishing is that they listen to the noise and try to make a career plan from that. “You have to write two books a year to be successful,” they hear, so they plan to write two books a year without considering whether they CAN write two books a year and, more important, if they want to give their lives over to writing two books a year. In the last McDaniel class, I have students make a career plan before I give them any information about publishing. I tell them to think about how they want to live their lives, what they want from their careers, what their priorities are, and then I make them write a one-year and five-year career plan. Usually, they panic because they don’t know enough about publishing to make a plan, but the plan isn’t about publishing, it’s about how they can live their lives as writers, fully and happily. They have to establish what they’re willing to sacrifice and what they must protect. Only then, when their signal is clear, do we start searching through the incredible amount of publishing noise that’s out there to figure out how to implement that plan. Only then can they look at agents and editors as partners in publishing instead of bosses or gatekeepers, someone they can bring their career plans to and say, “This is what I want; let’s talk about it and you can help me revise this plan to be practical and effective in light of what’s happening today.” Only then can they slow down, realize there’s no hurry, that they’re on their own timeline, and that finding the right publishing partners is infinitely more important that getting published fast. Making a publishing career plan is a hugely complex endeavor that requires regular revising, but the most important part is identifying your signal first. As long as you know your signal and use it as your guide, you’ll survive.

10. The most important thing I know about publishing: Write a fantastic book. Then do it again. That makes everything else about publishing so much easier.

June 28, 2014

Cherry Saturday 6 28 14

It’s Paul Bunyan Day. Buy yourself a blue ox. You deserve it.

June 27, 2014

Questionable: Story Form and Function

Mary (Egads) Wrote:

I’d like your thoughts on how form affects story.

I’m reading Alone With All That Could Happen: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom About the Craft of Fiction Writing by David Jauss. Jauss gives an example of student writing that failed to flow, not because of syntax, but because of form. The short story had six scenes, each scene was about the same length and structured the same. Despite the good writing, the story was dissatisfying because “the sameness of length made the story’s rhythm seem choppy, almost staccato, and worse, it implied that each scene was somehow of ‘equal’ importance, when some were clearly more dramatic and life-altering than others.” He speaks to the similar scene structure saying, “the effect of six consecutive sections of similar structure and length was oppressive… This student’s story failed to flow because it was, structurally, repetition without variation.”

This probably comes up as part of revision, but what do you think about when you consider how form shapes story? How do you use form to give weight or emphasis? How can form reflect what is happening in the story?

Oh, boy, that’s a book in itself.

The shape of the container becomes the shape of the thing itself; transfer something to another container and it will reform to fit that shape. So the shape you pour your story into becomes part of that story.

If you tell your story in a first/second/third/fourth chronological structure, the most important thing about that story will be the effect of cause and effect on the forward movement of the plot.

If you break your story into pieces and arrange them in a pattern that is not cause and effect, the most important thing in the story will be how those pieces relate to each other, the patterns they form in the reader/viewer’s mind.

Change the structure, change the story.

In the example given with six parts to the story, each the same, there’s no movement, no sense of rising tension, because each piece feels roughly the same. If the pieces are part of a pattern, that’s fine. If the pieces are part of a chronological, rising action, then you have a problem because there’s nothing about that structure that escalates. If you want escalation, make each subsequent piece shorter so that the turning point/endings of each piece come closer together. That picks up the pacing and increases tension.

But there are other ways that structure can inform story. If you’re writing a story set in farm country about someone who is reaping the outcome of an action, you can set the first part of the story in the spring when she sows the action, set the rising action in the summer when she copes with the fallout, and put the climax in August when she reaps what she’s sown. You can structure a story on the sections of a boat race, instructions for assembling a stereo, recipes, song structure, the seasons, the progression of a storm . . . anything can be a structure as long as it reflects and enhances the story you’re telling.

Most of my fiction is cause and effect; that is, the story begins when my protagonist does something, that causes the antagonist to do something, that forces the protagonist to do something, etc. Because I’m interested in the protagonist’s character arc caused by outside pressure, the classic, linear structure appeals to me because it pushes my protagonist to the breaking point.

However, that’s not the only kind of structure I’ve used. When I wrote short stories, I played a lot with structure.

“Just Wanted You To Know” was an epistolary story, a letter with four post scripts, so the story was in five parts that tracked how the writer worked through her grief and pain at being deserted by her husband. It’s chronological, but there’s no antagonist pushing against her so it’s five separate episodes about different people pushing her and where she ends up with each one, with a pattern in how she reacts differently to them each time. So even though it’s chronological, it’s much more of a patterned structure. I’d never try that form in a novel, it’d be awful, but for the short story, it worked the way I wanted it to.

I did another longer story called “I Am At My Sister’s Wedding” that was a first person narrative about a woman at three of her sister’s weddings and at one of the husband’s funerals (written so long ago it was before Four Weddings and a Funeral). It was patterned again because I wanted a story about this woman at four family functions, coping four times with trying to understand her sister and trying to deal with her father; she’s fifteen at the first wedding and in her late thirties by the last one. I went for patterned structure again because I wanted the reader seeing the parallels among the events but not necessarily seeing a progression. She changes each time because she’s older and experienced each time, not because of an event in the story. It’s not a step by step process, but more of an observation of the way she changes between the events which gives her a different outlook on the same things. Again, I wouldn’t do an entire novel like that, but for that story, that structure fit the best.

Every time you tell a story, you look at the best way to tell that story, to give it the shape it needs. Example: Watch Soderburgh’s Out of Sight paying close attention to the scenes. When it’s over, replay the movie in your head, putting the scenes in chronological instead of patterned order. The exact same scenes in a different order tell a different story, with a completely different emphasis, a story I would argue is much less. If you want an even shorter example, go find the love scene on You Tube and watch it, then re-imagine it so that first you see all the scenes in the bar and then you see all the scenes in the bedroom. Vastly different and vastly inferior even though it’s the exact same scenes. That’s the power of structure to give meaning.

Ninety percent of structure in today’s storytelling is classic, linear, cause and effect, so that’s what we talk about the most. But the only rule for structure in storytelling is that you have to have one, preferably one that informs the story you’re telling.