Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 264

August 26, 2014

Questionable: Character Names

Sharon S asked:

As a reader, I am always interested in finding out how and why authors choose the names of their characters. I’ve asked but never quite get an answer. I’m listening to Maybe This Time again. I’d forgotten Andy’s name is Andromeda. I’m guessing that is because of her strange mom? But what gives you your names? Please and Thank You.

Character names are really important, something I did not realize when I started writing. I picked names because I liked them, sort of like naming children. But on my third published book, I couldn’t get the heroine to work. No matter what I did, she was flat. So I sat and thought about her, about what she wanted, about who she was, and I realized she was a Lucy. I changed her name and there she was. I know it sounds dumb, but you ask any author and most of them will tell you that names are crucial for characterization.

Most of the time, my characters show up with their names. A few like Lucy have shown up with the wrong names, and Andie was one of those. I think I went through four different names before I hit on Andie, and then reverse engineered that to Andromeda because of her mother and because it would make North’s mother nuts (although she named her kids North and Sullivan, so she has no room to criticize).

My preference is for names that are different because they’re memorable. But different is not enough; that name also has to characterize because of stereotypes (Bertha is going to be large), associations (Alice connects to Alice in Wonderland, Tilda’s worldview was tilted), relationships (North’s character is diametrically opposed to Southie’s) and sound (Andie is a happy-go-lucky kind of name, Zelda is edgy, Agnes sounds like “anger” especially starting with that hard “Ag”). Other things I take into consideration: birthdate (different names are popular at different times), origins (tons of name lists on the internet, the last one I looked at was “Wolf Names”), what kind of people the character’s parents were (which explains how the name came to be and how they tried to shape the character as a child to fit that name), and how the name fits that character’s function in the text.

The McDaniel class does weekly chats, and last week I answered a question about names, using Bet Me as an example:

Min and Cal minimize risk and calculate the odds; they’re meant to be together. “Calvin” gives you an idea of how rigid Cal’s mother is, and Minerva gives you the set-up that Min’s mother was hoping for a goddess when her daughter was born.

Bonnie has a soft sound with that B at the beginning and the soft O that fits her softer nature. Liza has that razor sharp Z in the middle. I called the bridesmaids Wet and Worse because they weren’t on the page enough for the reader to recognize them by their real names; the nicknames also set up that Wet was the one who was always weeping for her lost boyfriend and that Worse was capable of much worse. Diana was another goddess name, plus there was the association with Princess Diana, the perfect daughter.

Cal, Roger, Tony, David. Cal’s the hero who calculates things. Roger is a dweebish name. Tony sounds like somebody who wears a baseball cap backward. And David is formal, business like.

One of the best ways I know to get a character firmly in mind before you write is to brainstorm his or her name. It’s like collage in that you’re working with associations: what does this name say to you about the character, how does it give clues to how he or she thinks, acts, talks, where he or she comes from, etc. A character named Poppy is different from a character named Rose; a character named Andromeda is different from a character named Diana; a character named Phineas is different from a character named Harry, and so on. Thinking about the name makes you think about the character in a different way.

August 23, 2014

Cherry Saturday 8-23-14

Today is Ride the Wind Day, described as a day to soar above the earth.

You know, just watch Up again. That should do it.

August 21, 2014

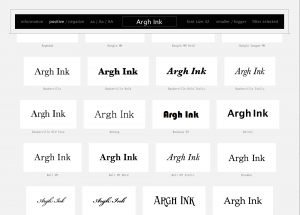

Great Site: Wordmark

If you’re a font-lover (I am, I am) but it makes you crazy trying to figure out which font will look best for the design you’re working on, go to Wordmark immediately. You type the words you want to preview in the box, hit the “load fonts” button so the site can access your font list and you get this:

My design life just got SO much easier.

Via Lifehacker.

August 19, 2014

Questionable: Staying Attached When Characters Do Unlikable Things

Sure Thing asked

How do you manage to place your characters in difficulties/conflicts that are still emotionally readable? . . . You still create vulnerability in your characters but nothing that makes me feel they are too flawed . . . . How is it that they hurt, or do hurtful stuff (Cal) and I still want to keep reading?

Here’s my theory on that, without comparing myself to anybody else because I can’t speak for anybody else’s process.

It starts and ends with character. Any realistic character has strengths and flaws, and those strengths and flaws are often mirror images.

Since you brought up Cal, he’s a good, loyal friend, empathetic and concerned about others. Because of that he’s also sensitive about things that might hurt them and (the part that’s hidden but the reader knows is there) himself. So while you admire Cal for his charm and the way he listens to Min and tries to understand her, it’s not out of character when he blows up at the end because he thinks she was playing him. (It is, however, a Big Misunderstanding, and I’m not proud of that at all.)

Or take Bill in Crazy For You. He’s a great teacher and a great coach, sure of himself and in control of his classroom and his team, a terrific role model. But the flip side of that is that he can’t lose control and he can’t see anyone else’s world view, so what works on the football field (play hard, play fair) becomes dangerous in the complications of adult life. When he starts to lose it, it’s not a character violation, it’s a logical extension of who he is, just pushed to its limits. Doesn’t mean you forgive him, but it does mean, I hope, that you understand how he got there.

I think one mistake authors make (no author in particular, just in general) is saying, “Yes but he had this lousy thing happen in the past [see prologue] and that explains why he’s like that now.” First, it doesn’t explain anything. People can come out of the same traumatic experience and take vastly different paths. Second, what happened then isn’t important, it’s what the character is doing now that establishes our attachment to him. A dog bit him when he was twelve, so he kicks puppies now. Lots of people have been bitten and do not kick puppies, and beyond that, we’re watching him kick puppies now. We don’t like him.

So understanding why a character does something is half of solution but only if because it’s part of his personality (“he’s cautious about relationships” not “he was abused as a child”) and we see it in dimension (“and that makes him a careful judge of character and especially protective of children”).

The other half is that the character makes amends. Bill can’t apologize because he still thinks he’s right, so he’s going to jail. When people explain to Cal what he’s done, he apologizes without reservation and then goes beyond that; he grows, he changes, he commits. He’s forgiven. That puppy kicker better start his own no-kill shelter and take down a dog-fighting ring if we’re going to forgive him.

If you create a character with strengths and flaws and demonstrate them on the page so that the character becomes three-dimensional, her screw-ups become forgivable because she’s human and everybody screws up, but only if she sets things to right. If she creates pain and chaos, then she has a responsibility to clean up the mess. If she does that, we can maintain our attachment to her because we’ve been there, too.

One other aspect is important in establishing sympathy for a character: vulnerability. If he’s a master of the universe, then even if he hurts someone and apologizes sincerely and politely, we’re not going to be engaged because he’s invulnerable. The apologies that are the most devastating are the ones that cost the character real pain to make because they make him or her vulnerable, not just admitting that he made a mistake, but making it clear on the page that the admission is painful, that it hurts him that he’s hurt others, that it matters to him beyond social courtesy. Establishing your characters vulnerabilities through small things throughout the story can make their transgressions more understandable and their apologies more acceptable, and therefore maintain our sympathy with them.

August 16, 2014

Cherry Saturday 8-16-14

Today is National Tell A Joke Day.

Knock yourselves out.

August 9, 2014

Cherry Saturday 8-9-14

Today is Book Lover’s Day. Or as the Cherries call it, Every Day.

August 5, 2014

Howdunit: Writing Mysteries

So after five years of beating my head against the brick wall that was Lavender’s Blue, I’m starting over. The flaws were in the protagonist (negative goal), antagonist (confused motivation), the conflict (intermittent), and the plot (wandered all over the place). I’d been duct-taping over the holes in the story for so long it was 95% duct tape. A beta read by Toni Causey finally made me see the light: No More Duct Tape. Time to build a new book.

Oh, and one other thing: the mystery sucked.

So for the past several weeks, besides finishing my kitchen (not done yet but so much closer), I watched as much mystery TV as I could (my iPad wouldn’t recharge so I had to wait on reading mysteries), and found out that outside of Britain, there’s not a helluva lot of TV mystery writing going on. Thrillers, yes, but really good, old-fashioned, follow-the-clues mystery? Not so much. The search has taken me in some interesting directions, but what it’s mainly shown me is how much modern series are more about character, mood, relationships,and snappy patter than they are about puzzles. It’s not that I think that a mystery should be only a puzzle, but just as a romance has to be a love story, I think a mystery should be a puzzle, a problem to solve.

Some of the shows I watched were a lot of fun, but really weak on plotting. Phryne Fisher comes to mind here: marvelous sets and clothes and a fun community but the mystery plots are pretty contrived. That actually adds to the period feel; a lot of the golden age mysteries were contrived. (I did my first master’s thesis on women’s roles in early mystery fiction. Trust me, Baroness Orczy makes Phryne look like Jane Tennison.) There’s an American detective series called The Glades that has a charming detective hero who evidently has the brains of a grape because he keeps arresting the wrong people in the most embarrassing situations possible; he also evidently has enormous good karma because nobody ever sues him for false arrest or harassment. These shows coast on mood and character which makes them really fun the first time through and almost unwatchable the second time because looking really closely at the stories shows plot holes big enough to drive the Orient Express through.

The shows that do hold up seem to fall into two categories: British and mid-twentieth century. The British pretty much own the classic murder mystery so that’s no surprise, but what’s been great is how well their new stuff holds up, too. Gillian Anderson’s The Fall is complex and detailed but still scrupulous with clues, although the puzzle aspect is Columbo-like: we meet the serial killer before we meet the detective, so it isn’t whodunit so much as how is the detective going to catch him? Inspector Lewis is my favorite whodunit detective, so I’m happy he’s coming back for another season, and I thought Foyle’s War had excellent plots, too.

And speaking of Columbo, that holds up really well, in part because the episodes are so long–I’d forgotten they were basically two-hour movies–and because they such good people worked on them. I’ve just started rewatching those and tripped over one written by Steven Bochco and directed by Steven Spielburg. And then there’s the quality of their villains: Gene Barry, Lee Grant, Jack Cassidy, Robert Culp, Eddie Albert, Ross Martin, Roddy McDowel, Patrick O’Neal, all great seventies character actors having a wonderful time patronizing Peter Falk until he defeats them utterly. Makes me want to set Liz in the seventies and give her a wrinkled raincoat.

What all of this mystery watching has done, though, is reinforced the importance of plot. I’ve always thought that character was more important than plot, but watching so many different stories has shown me that while character tap dancing can gloss over a lot of plot holes, as the dance goes on, the characters start to fall through the holes, charming though they are. And that’s left me with some general thoughts about mystery writing that I’m still trying to work out. Note, that’s “thoughts,” not “rules.”

1. The criminal has to be really smart and really interesting.

The detective on The Glades is not the sharpest knife in the drawer, but the criminals are all spoons. They’re also fairly unlikable without being entertaining about it. Watching Jack Cassidy being an absolute bastard on Columbo makes watching Peter Falk catch him SO much more fun; especially since he’s a smart bastard. And the episode with Robert Culp, an accidental murderer with brains and power, reminded me of a great Criminal Intent episode in its cat-and-mouse interaction between the law and the killer. It’s the old rule: the antagonist has to be as smart as or smarter than the protagonist or the struggle’s not worth watching. This is one I’m still working out because my original antagonist was very smart, but the character I’m thinking of as a replacement is dumb as a rock. That’s not going to work. Must cogitate.

2. The detective has to be intuitive and detail-oriented to earn his or her victory.

Too many of the shows I watched were the equivalent of the detective barging around and then tripping over the answer because he or she got lucky, while doing a jazz hands smoke screen of snappy patter with comic associates. I realize that luck plays a role in real life, but in detective fiction, it’s right up there with coincidence as a thing-we-don’t-believe. So the detective in Lavender’s Blue is Liz, who’s detail and research oriented, but it’s also Vince, the local cop, who’s analytical in a different way. The key there is going to be differentiating them, giving them different strengths or they’ll just be repeating each other.

3. Really good detectives don’t foreground themselves.

Columbo shuffling around, Rockford doing a weekly equivalent of just being on his way to Australia, Lewis painstakingly following clues while Oxford snobs sneer at his class: the stealth approach to detecting just makes more sense than arriving as the Great Anything (unless you’re Sherlock Holmes). That works with Vince the cop who’s in the background most of the time and likes it that way, but Liz tends to attract attention, not on purpose but because of who she is. I think I can make that work for me, though.

4. The clues should be in place by the beginning of the fourth act at the latest, and possibly by the beginning of the third act, because discovering the last bit right before the arrest/confrontation kind of takes the fun out of the mystery. Ellery Queen used to have a page about halfway through his books that said something like “And now you have all the clues to this mystery” so you knew that the puzzle was done and you should be able to solve it. Granted, Ellery Queen wrote some pretty out-there mysteries, but at least the writers played fair in giving the reader time to solve the puzzle. This is where I have a big problem in my mysteries: I like seeing what caused the murder, so my victims usually don’t even die until halfway through the story, and I think that’s going to happen again here, which could be a problem. Argh.

So basically, starting over on Lavender’s Blue, I’m looking at the mystery plot first this time. Of course, I can do that because I’ve got all the characters in place and all the emotional subplots clear, but still, this is the first time I’ve thought, “Plot comes first, character second” and started designing clues and red herrings. In the meantime, I’m going to keep studying mysteries–I’ve finally recharged my iPad so I can read some, too–and, as God is my witness, I will figure out how to do this.

And as part of my research, I want your thoughts. What are some mystery titles–books and film–that you think are stellar? What annoys the hell out of you about some mysteries? Are there any unbreakable rules to mystery writing? Most of all, what makes a good mystery?

August 2, 2014

Cherry Saturday 8-2-14

Today is National Mustard Day. See if you can cut it.

July 26, 2014

Cherry Saturday 7-26-14

Today is All or Nothing Day. That’s so stupid, I can’t even make a joke about it. How about “Sing Show Tunes With Drinking Lemonade” Day? That at least has a POINT.

July 23, 2014

Not Dead Yet

I know, I know, I haven’t blogged. Much stuff going on, most of it in my head, including how to finish up the Leverage stuff when I’m so conflicted about the finale and need to go back through all the posts and make them make sense, how to save Lavender’s Blue which I’ve come to the conclusion means cutting about 35K of the 50K I have and starting over, getting my kitchen finished now that I have FINALLY figured how to build the last of the storage, and about forty other things. The McDaniel classes are finished, so that was a sad/glad moment; new classes are scheduled to start (I think) in January, but don’t quote me on that. Talking with Alisa and Pam about doing a one-off class on writing the romance graphic novel which Alisa would teach (same class she taught at Fordham) and I would take because I nee to learn that stuff, so whoever got stuck in that class would have me asking annoying questions all the time. Generally just trying to sort everything out here. I’ll be back, I swear.

So what’s new with you?