Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 159

April 9, 2019

Questionable: Can a Love Interest Be an Antagonist?

K asked:

“I have a question about villains – and layering them so that they engage with each other and the heroine. Some say the hero (love interest) is the main antagonist, others say there needs to be a stronger antagonist because he’s not one by the end. What say you? What have you found works the best? Do more antagonists pop up as you write? How do you like to layer them? Do you have a limit/rule that you like or use?

Let’s start with the basics.

The protagonist (not the hero) of a story owns it; her need to reach her goal and the actions she takes to get there are the reason the story moves forward.

The antagonist (not the villain) of the story shapes it; his efforts to block the protagonist and reach his goal determine the story’s path and the escalating conflict.

Example: Without the antagonist, Indiana Jones would say, “Oh, there’s the Ark of the Covenant” and go pick it up. Because Belloq the Nazi archeologist has it and keeps blocking him, Jones has to go find Marion, travel to the Middle East, battle snakes (he doesn’t fall into the snake pit, Belloq pushes him in), and hitch a ride on a U-Boat before he can rescue the girl and the world. Without Belloq, there is no Raiders of the Lost Ark.

So you need one protagonist and one antagonist per story, or your plot ends up being a lot of cats running around, barging into each other. The antagonist can have minions, witting or unwitting, but there has to be one Big Bad to guide them all with his master plan. Same with the protagonist who can have friends and partners and teammates, but she alone has the goal that fuels the plot.

I’m going to repeat this because it’s important: The antagonist is not the villain, he’s just the character who pushes back against the protagonist, who is not the hero. Giving a moral dimension to those character roles as you think them through can skew them into cartoons. Nobody gets up in the morning and says, “Today I’m going to be an evil son of a bitch.” Don’t give that attitude to your antagonist because it’ll flatten his characterization.

As to whether the hero, which you’re collating with “love interest,” can be the antagonist, that depends on the story. I wrote about this over on Writing/Romance, so here’s a link to a more detailed explanation: https://writingandromance.wordpress.com/2015/10/26/conflict-in-romance-plots/

The short version of that post is, if your plot has the love interest character blocking your protagonist from her goal, then the love interest is the antagonist (see Moonstruck). If your plot is the protagonist vs somebody else, and the love interest comes in to help her fight (see Charade), the love interest is not the antagonist. It’s much easier to write a romance where the antagonist is not the love interest because a good climax has the protagonist utterly defeating the antagonist or vice versa. That’s a bad start to a relationship unless the defeat in some way sets the other character free. Again, there’s more on that at the link.

The key to deciding protagonist and antagonist in your story is to jettison the value labels–heroine, villain, love interest–and think in term of character functions.

• Whose pursuit of the goal drives the main story? That’s your protagonist.

• Whose pursuit of a goal blocks the protagonist’s pursuit and shapes the plot of the story as she or he pushes back? That’s your antagonist.

Or even simpler, who, if you removed him or her from the book, would cause the conflict to collapse? In Nita, I’m finding it pretty easy to delete Mort. I could even lose Nick, and Nita would still be dealing with Lemmons and rotten rangers. But if I took out the Cthulhu character, Nick wouldn’t come to Earth and there’d be no supernatural crime for Nita to investigate. There’s my antagonist.

The post Questionable: Can a Love Interest Be an Antagonist? appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 8, 2019

Questionable: What’s the Difference Between YA and Adult Fiction?

Johnna asked:

“What makes YA novels so popular nowadays with adults? And is the line between adult and YA fiction really there anymore, especially in fantasy and science fiction? I know that you aren’t a YA author, but with Nita, for example – is there a reason why your book couldn’t/wouldn’t be in a high school library? (other than perhaps sex scenes?)

As Cate said in the comments, the big determiner of YA is the age of the protagonist. A YA protagonist does not necessarily mean that the book is a YA, but an older protagonist pretty much means it isn’t. YA readers have too much adult PoV in their lives already; they want to read about people like them solving problems and making connections. The focus is also likely to be on different things. YA dystopias are different from adult dystopias; YA romantic conflicts are different from adult romantic conflicts. It reminds me of something somebody said about the difference between pop and country music: pop is about falling in love and country is about working on your second divorce. YA fiction is about becoming an adult and adult fiction is dealing with being an adult.

As for why they’re so popular, a lot of them are well-written and many of them are more imaginative and lively than adult fiction, possibly because their protagonists are still imaginative and lively, not beaten down by reality and the electric bill. And for adult readers, there may be the lure of reading about a simpler time (HA! Do you remember junior high?) before responsibility raised its ugly head. But basically, a zillion adults read the Harry Potter books because the Harry Potter books were good. Same for the rest of YA. A good story is a good story.

YA can have sex scenes; there’s a reason Judy Blume’s Forever will forever be a classic. YA readers want to know about sex, too, and since they’re having it earlier and earlier, they’re not nearly as innocent as many people would like to believe. What they are is clueless (something they have in common with many adults) about what sex can mean and what can happen to you both physically and emotionally if you’re cavalier about it. So if you’re writing sex in a YA, be very, very careful, because those young readers are taking cues from music videos and movies and TV shows and their equally clueless peers, and they’re primed for big mistakes; don’t be part of the problem. Don’t get moralistic or didactic, but be real, if for no other reason than disasterous sex is more fun to write than best-sex-ever sex.

And specifically, on Nita? If Nita and Nick were fifteen, the story could be a YA, but the sex scenes would be vastly different plus their freedom would be very limited as teens. At 33, Nita is pretty jaded about sex and at 529, Nick is remembering his long ago history as a playboy crook. Nita can also go anywhere anytime she wants, answering to nobody but her boss; if she were 15, she’d have curfews and be explaining things to Mitzi and the Mayor (her parents). Nick might have an easier time of it at fifteen, since in the terms of the plot he’d still be dead and his parents gone, but if he were a legitimately YA protagonist, he’d still only have the social and political experiences of a fifteen-year-old, so the whole Master of the Universe thing would be gone. YA stories are more about learning the world and taking control of it than already having that control and figuring out what to do with it, so I could write Nita as a YA, but it would be a very different book.

The key is, you really have to understand kids on their level to write a great YA, and then see that story world through their eyes, with their constraints and their lack of experience, while capturing the endless possibilities of youth. I couldn’t do it, even with fifteen years of public school teaching behind me. It’s a wonderful genre, but it’s really tough to do well.

The post Questionable: What’s the Difference Between YA and Adult Fiction? appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 7, 2019

Moment of Joy

How did you find your moment (or many moments) of joy this week?

The post Moment of Joy appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 6, 2019

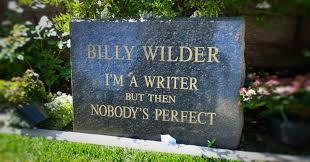

Cherry Saturday, April 6, 2019

Today is Plan Your Epitaph Day.

Mine is “Nothing But Good Times Ahead.” What’s yours?

The post Cherry Saturday, April 6, 2019 appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 5, 2019

Questionable: Can You Put a Death in a Rom Com?

S asked:

“What do you think about death in the romantic comedy? Not the hero or heroine, but someone else who matters. Does this make it something other than romcom? Would readers revolt? Have been studying 4 Weddings and a Funeral – the writer was apparently advised to include the funeral to balance the sweet. . . . Had similar thoughts about the movie The Apartment which was tragic but listed as a romcom. It’s for my WIP – my critique grip is squeamish about a death I’m planning in a book that’s part of a romcom series and I’m wondering if it’s maybe too much for my reader?”

Well, first define “romantic comedy.” I’ve never thought The Apartmentwas a romantic comedy, so I’m no help there. My basic definition is that it’s a story of a romance that ends happily and is funny. If you can make a death work in that context, it’s a romcom. Obviously, there’s some calibration in there, but death is not antithetical to romance or comedy.

Here’s the thing about happiness: it exists in contrast to unhappiness. You cannot have highs without lows. Psychologically, you need both joy and pain to fall in love. Most romcoms bollix this up by using the Big Misunderstanding, which causes the lovers enough pain that they break up or turn on each other. But the Big Misunderstanding is stupid, makes the lovers look stupid, and is one of the main reasons people sneer at romcoms (along with the fact that romcoms are hard to do so there are a lot of really bad ones out there). There needs to be a real reason these people feel pain, enough pain to wake them up, make them grow up, move from the infatuation stage to the commitment stage.

Death of a loved one is big pain, not just for the characters but also for the reader if she was invested in the lost one. The problem is calibrating the pain. If it’s so overwhelming that the reader can’t get past it and sees the lovers going on to happiness and thinks, “How could they?” the whole meringue of romantic comedy falls flat. Of course, that’s true of any genre; I’m still not over the death of that puppy in John Wick. So the key is to make the lost one somebody that will have an impact on the plot and characters, but not be so overwhelming that the reader can’t recover from it. And in a comedy, that has to be negotiated VERY carefully.

One of the best short stories I’ve ever written is “I Am At My Sister’s Wedding,” done in four parts (four acts, five weddings), and in the third act, the narrator’s mother dies and so does her sister’s fourth husband, the good guy she finally got. It has such a huge impact on the narrator that she has an epiphany at the husband’s funeral, and then later makes a big decision at her sister’s fifth wedding because of that ephiphany. It’s a comedy because the narrator has a sharp tongue and is a real smart ass, but I’ve always thought it was really sad underneath because the narrator was so unhappy all the way through and mouthing off to hide it; that comes straight from one of my two biggest writing influences, Dorothy Parker, a writer who can make you laugh and weep at the same time. Still my MFA class thought it was funny as hell, and it had the deaths of two good people in it. Just not the narrator’s sister; she was too important and her loss would have sent the narrator too far into darkness, or her best friend, the only one who understood her, which would have left completely alone. In an earlier draft, that best friend who was gay died of AIDS (this was the nineties and one of my best friends had just died of AIDS) and it was too damn much. The mother was a vivid and important character, and the fourth husband was a good guy, but the reader could roll with losing them in a way they couldn’t with this close friend character or the sister who’d both been on the page a lot more.

But your question is more complicated because you’re also talking romance, an essentially happy genre. The good news is, pain is an integral part of romance. The relationship needs to be tested, the lovers have to feel pain and still decide to stick to each other, or nobody will believe they’ll make it. It’s just too easy to fall out of love when the bad times hit, so most romances incorporate bad times. And dealing with grief is one way lovers can bond, even beyond the way it can make a character grow up enough to enter an adult relationship.

So of course you can do it if you calibrate it so that it’s not overwhelming to the reader, and if the death has meaning within the story. No offing a character just because “sometimes people die;” that’s lousy writing. (“I am a leaf on the wind. Watch how I soar.” Whedon’s going to Writer Hell for that one.) The death has to be earned. It has to mean something important to the story, not just be there to jerk tears or give protagonist pain.

The death in Four Weddings wakes up the hero, who says after the funeral that while they were all running around talking about marriage, they’d failed to see that two of the group were married all along, their two friends who had a wonderfully joyful committed relationship but couldn’t tie the knot because they were gay. But it’s so much more: John Hannah’s reading of that damn Auden poem at the funeral will make me weep no matter how times I see it; it’s the purest example of love in the whole movie, so it also underscores the romantic theme. Hannah’s character may have lost the great love of his life, but he had that love. He hadn’t ducked it from fear or a need to fit into society, he had loved with all his heart, and that gives the protagonist the realization that he’s living a half life because he won’t take the chance. It’s integral to the story.

So the key, if you need a death, is to make it somebody who resonates but who we can spare; somebody to whom attention must be paid, but not too much attention; somebody whose death is integral to the plot (and not just for fridging purposes) and acceptable to the reader. Yeah, it’s a narrow road to walk, so don’t kill the dog or small children. (I kill the dog in Nita, so ignore that, but small children? No.) Just make it matter, to the reader, to the story, to the characters. Attention must be paid.

Just not too much.

The post Questionable: Can You Put a Death in a Rom Com? appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 4, 2019

This is A Good Book Thursday, April 4, 2019

I’ve been reading about trauma and food and murder, not all in the same book of course. Although that would be a good book. What did you read this week we should know about?

The post This is A Good Book Thursday, April 4, 2019 appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 3, 2019

Working Wednesday, April 3, 2019

Oh, thank god, it’s spring. Well, it’s spring where I am, apologies to everybody in Southern Hemisphere, but there it’s fall and I love fall, too. It’s those transition seasons; you just can’t beat them for great energy.

So what work did the season change inspire you to this week? Or, you know, what did you work on in general?

The post Working Wednesday, April 3, 2019 appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 2, 2019

Questionable: How Can the Concepts of Fiction Apply to Non-Fiction?

Debbie wrote:

I write nonfiction (for work). But I find that many of the things you focus on–particularly the importance of the first scene, and timing–are helpful for both my written work and my presentations. I’m not sure that’s a question, exactly, but it would be interesting to talk about how many fiction rules also apply to non-fiction.

Kelly commented:

I’d like to expand that question to how much can be applied to presentations too, unless that’s getting too far beyond writing?

Nonfiction and fiction are different, of course, but there are some parallels.

The big thing in both is that you’re trying to hold an audience to get one main idea across. And in both, you’re dealing with a retention problem, so first you have to grab your audience, and then you have repeat your main point/focus/intent/theme so that they’ll retain it while you’re being tremendously entertaining so they’ll listen, and then you have to hit that main point hard at the end so they’ll remember it.

The most obvious way to figure out the main point is answering the “What is this this essay/report/presentation/story about?” question. If you can’t get your central idea/question/intent into one sentence, you don’t know what the piece you’re writing is about, and it’s going to go all over the place.

And you need to know because you can only have one main point. Here’s a depressing fact: even the most attentive reader/listener retains about ten percent of what he or she reads or hears (assuming she only reads the book/essay or sees the presentation once). It’s just the way our brains work. So to make sure you get your main point/theme/thesis/intent across, you follow the old preacher’s formula:

• Tell ‘em what you’re gonna tell ‘em.

• Tell ‘em.

• Tell ‘em what you told them.

You obviously do not repeat anything, you say it differently every time, but you stick to that one main point and everything in your story/essay/presentation sticks to that point. Because at the end of the story/essay/presentation, that’s the thing you want the reader/listener to walk away with. It’s more subtle in fiction; I assume most readers don’t know that the theme of Faking Itis that honesty is the only way to connect, not only to other people but to oneself, but readers might very well say, “I loved it that at the end they had great sex because they told each other the truth, and in the big climax they were there for each other because they trusted each other.” Fiction is squishy about theme; it has to be there but it shouldn’t be obvious on the page. But in non-fiction, it should be obvious: This is what this book is about.

So you start (tell ‘em what you’re gonna tell ‘em) with a hook that is about the main point.

The Devil in Nita Doddis about a woman who’s been an outsider all her life, so it opens with her sitting in a cold car with a stranger, trying to sober up so she can understand what’s going on, totally disconnected from herself (she thinks, Don’t be odd, Dodd, when she is in fact odd at a cellular level). In a book about outsiders coming in from the cold, the outside protagonist has to start in the cold to have somewhere to come in from.

Non-fiction is the same, just blunter. Bessel van der Kolk in The Body Keeps the Score,starts off with “Trauma happens to us, our families, and our neighbors. Research by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention has shown that one in five Americans was sexually molested as a child, one in four was beaten by a parent to the point of a mark being left on their body, and one in three couples engage in physical violence. A quarter of us grew up with alcoholic relatives, and one of eight witnessed their mother being beaten or hit. . . . traumatic experiences do leave traces . . . on our minds and emotions, on our capacity for joy and intimacy, and even on our biology and immune systems.” His thesis: Trauma is all around us, it’s common,and it changes us at the cellular level in our bodies and our brains. He doesn’t hide that idea, he hits us with it in the first paragraph.

The rest of the story/presentation/essay continues to tell us that right up to the end. It tells us in the different ways it shows or argues that thesis is true, in the different aspects of the problem/thesis/plot, in escalating scenes and acts and character arcs; it expands on that core idea, adding other ideas, new characters, subplots, examples, anecdotes, arguments; but it always, always connects in some way to that main theme. It’s the writing equivalent of the old Hays Movie Code that said if two people were in the same bed, they each had to have one foot on the floor. You can have a lot of ideas in your story/essay/presentation, but you have to keep one foot on your main idea at all time because the middle is you telling ‘em, it’s the reason you’re writing what you’re writing.

Then you get to the end and you nail that thesis to the wall by telling ‘em what you told ‘em. Your odd protagonist has found her community and is surrounded by friends who are equally odd, and she’s connected and happy and warm at last. Van der Kolk’s final sentences are “Trauma is now our most urgent public health issue, and we have the knowledge to respond to it effectively. The choice is ours to act on what we know.” That’s what he wants you to walk away with, the knowledge of how common trauma is, the huge impact that it has on us, and the call to deal with it because we can. The end is the last place to nail your thesis, and it’s the best place because it’s the part people remember most.

Tell ‘em what you’re gonna tell ‘em, tell ‘em, tell ‘em what you told ‘em.

The only other parallel between fiction and non-fiction that I can think of offhand is that teaching by analogy with narrative is the most effective way to write non-fiction or make presentations. Obviously, fiction is all narrative, but when it comes to the non-fiction task of getting ideas across, stories do it better than abstract statements. That’s why van der Kolk’s book is full of stories about trauma and how the affected people recovered. I won’t remember the technical terms about brain scans and brain parts when I’m finished with this book, but I’ll remember Ute and her blank brain scan forever.

The big thing, though, is that at the end, you revise for that controlling idea, no matter what you’re writing. Keep one writing foot on the thesis, and you’ll be fine.

The post Questionable: How Can the Concepts of Fiction Apply to Non-Fiction? appeared first on Argh Ink.

April 1, 2019

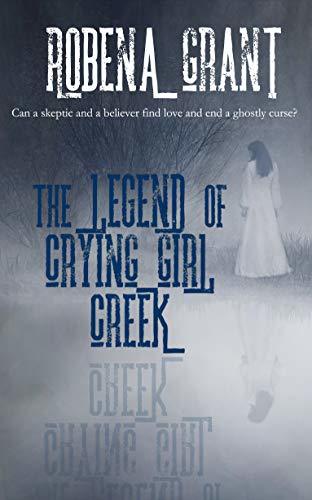

Argh Author: Robena Grant’s The Legend of Crying Girl Creek

Our Roben went home to research her latest book: “I enjoyed doing the research on this book, as it required a couple of extra trips to Australia. That’s always fun to catch up with relatives. The setting of the book is only a half hour drive from my mother’s home, and it is where I grew up. The research added some historical details to the story that dated back to the early penal colony, and the convict built Great North Road from Sydney to the Upper Hunter Valley.” The book is The Legend of Crying Girl Creek, and if you act fast, like right now, it’s at a great price.

Adventurous American nurse Samantha Winters is on a study abroad program in Australia. But after one perfect night with a handsome stranger, she finds herself with child. Intrigued with an elderly patient’s tales of a local creek where pregnant women drown themselves, Sam agrees to help end the curse. Historian James Campbell keeps a vigilant watch on his family’s haunted land, hoping to prevent more deaths. A loner in his personal life, he’s stunned to discover his grandmother’s nurse is the one woman he can’t forget. Sam is a believer. James is a skeptic. With the legend’s anniversary looming closer, the two work together to solve the mystery of Crying Girl Creek. Amid the tangles of secrets and lies Sam has a secret of her own: James is the father of her baby. And he doesn’t want children.

You can find out more at Roben’s website, or just go straight to Amazon and hit that buy button.

The post Argh Author: Robena Grant’s The Legend of Crying Girl Creek appeared first on Argh Ink.

Questionable: How Do You Show What the PoV Character Doesn’t See?

Sarah asked:

My question is about how to write a book in one PoV only, while still implying someone else’s PoV. I’ve seen it done (clumsily, I think) in many many books: the PoV MC will say something off-hand to a potential lover (John) and the author writes, “John paused for a moment before replying, as if her remark had hurt him.” That seems to me to be cheating: the PoV MC is meant to be oblivious of John’s real feelings at this point, but the author shows us the card anyway. How blatant do I need to be in using the PoV MC to reveal someone else’s feelings? I know I need to a bit, but I’m struggling between clumsy (as above) and so subtle no one else gets it.

S

Unless you’re writing in third omniscient, you only get one point of view, no implying others. So let’s review PoV first, then I’ll answer your specific question. There are four PoVs to choose from: first person, second person (don’t pick that one), third person omniscient and third person limited.

In first person, you’re in one person’s head as “I,” so you’d write “I saw John pause for a moment as if my remark hurt him.” There is no doubt that it’s the narrator’s observation so she saw him and interpreted that. John may be thinking something completely different, but the narrator has to have seen him pause to come to that conclusion.

In third person omniscient, you’re God, so you’re in everybody’s head and making comments: “Jane told John it was none of his business, and of course John took that personally, which Jane missed completely because she’s so self-involved. Of course, John took it personally because he thinks the world revolves around him. These two people are selfish and deserve each other.” That’s God, seeing all, knowing all, passing judgment. (Terry Pratchett is a master of this PoV.)

In third person limited, which is what your example is, I’m pretty sure, you’re in Jane’s head and only Jane’s head, seeing and hearing and feeling only what Jane sees and hears and feels, so if “John looks hurt” is on the page, then Jane sees that and knows he looks hurt, and you’re right, you can’t cheat and pretend she’s missed that, she saw it.

So how can you stay in rude Jane’s head and show John being hurt without Jane noticing in third person limited? (Yes, we’re finally back to your original question.)

You give Jane something to notice that she dismisses but the reader thinks, “Ouch, that hurt.” So Jane says, “This is none of your business, John,” and John steps back, and Jane thinks, Good, he got the message, and moves on, and the reader thinks, “You hurt him, you bitch.”

But to be sure that’s going to work, you need to have laid in the groundwork first, building characters as you tell the story. If throughout the course of the story, the reader has learned that John desperately wants Jane’s respect and affection, then when Jane dismisses him offhand, the reader already knows he’s going to be hurt, so even a minimal action like his stepping back or even just blinking confirms that. And Jane can continue being clueless.

Here’s the thing: One of the great pleasures of reading fiction is getting to know the characters through their actions. The reader seeing John trying so hard through several scenes without anybody saying, “Wow, John is trying hard,” means that when the reader interprets that, she’s connected to John. And that means that when Jane says, “This is none of your business,” the reader reacts with John, even if she sympathizes with Jane. She knows them both, she’s invested in them, and she cares about their story.

Plus, you get the added benefit of showing your reader that you respect her. It’s really insulting to have everything in a story spelled out for you—“I’m telling you John was hurt because you’d never figure that out on your own, you dummy”–but a story with character clues that lets the reader build an understanding of character is a story that respects the reader and makes her feel smart and part of the narrative. At that point, a story can become almost a Rube Goldberg machine for the reader, so many moving parts meaning so many different things, creating a rich tapestry of characters in motion. Which is so much fun to read.

If you’ve just arrived at John’s pain, not having realized it was there before, you can always go back and layer the foreshadowing in the rewrite. If you don’t foreshadow, his pain comes out of left field, and your reader is likely to miss it, since PoV Jane does. So plan ahead and get your reader involved, and you’ll be fine.

Dahlia commented:

The reason I don’t like most modern first person is because it’s often badly written. It’s tell in the skin of show. For me, first person is difficult. If you want to write it, try switching it to third, or writing it in third and switching it to first. It should track.

First person and third limited seem alike but they’re vastly different because first person is very, very, very close and third person limited has distance (not as much as third omniscient, but still distance). A voice that’s entertaining in first person will be way too personal and annoying in third. A voice that’s authoritative and unobtrusive in third person will be flat in first. A story in first switched into third will have way too much interior monologue. A story in third switched into first will be powered by a character with very little internal life. It’s like trying to take a ballad and redo it as rap. You can do it, and the results may work, but you’ll need to do some heavy duty rewriting and reconceptualizing, and the flavor and meaning of the work will change drastically. It’s not just switching pronouns.

The post Questionable: How Do You Show What the PoV Character Doesn’t See? appeared first on Argh Ink.