Gary Mesick's Blog, page 3

September 30, 2019

Moments Like This Make it All Worthwhile

Moments Like This Make it All Worthwhile

West Point Mess Hall --

West Point Mess Hall --

Not Your Ordinary School Lunch Room

It's fine to say that I write for myself. But if it were true, I wouldn't bother to show the poems to anyone. Even Emily Dickinson, at her most reclusive, had an audience of one with whom she shared her poems before rolling them and tying them with a ribbon and stuffing them in a desk drawer. I want to share my poetry, and I want it to mean something to others.

I was at my 40th reunion last week at West Point, and I gave a copy of General Discharge to the son of one of my classmates while we were having brunch in the cadet mess hall. The book got passed around, as books sometimes are, and one of the others sitting at the table flipped through it, came upon a poem ("Inquisition," for those of you keeping score at home), and barked out a loud laugh.

That in itself was marvelous, but then she said, "I have to take a picture of this and send it to my friend." So she did.

I couldn't have asked for a better response--or a better place for it to have happened. Back at West Point, among those who have similar stories to tell. It meant enough to her to share it with someone else.

West Point Mess Hall --

West Point Mess Hall --

Not Your Ordinary School Lunch Room

It's fine to say that I write for myself. But if it were true, I wouldn't bother to show the poems to anyone. Even Emily Dickinson, at her most reclusive, had an audience of one with whom she shared her poems before rolling them and tying them with a ribbon and stuffing them in a desk drawer. I want to share my poetry, and I want it to mean something to others.

I was at my 40th reunion last week at West Point, and I gave a copy of General Discharge to the son of one of my classmates while we were having brunch in the cadet mess hall. The book got passed around, as books sometimes are, and one of the others sitting at the table flipped through it, came upon a poem ("Inquisition," for those of you keeping score at home), and barked out a loud laugh.

That in itself was marvelous, but then she said, "I have to take a picture of this and send it to my friend." So she did.

I couldn't have asked for a better response--or a better place for it to have happened. Back at West Point, among those who have similar stories to tell. It meant enough to her to share it with someone else.

Published on September 30, 2019 08:15

May 16, 2019

Some Poems Worth Your Time: Keith Douglas -- "How to Kill"

Some Poems Worth Your Time: Keith Douglas -- "How to Kill"

Keith DouglasThis is another war poem, by another British soldier, from another war. And for me, its power comes from the way the poem's speaker demystifies the act of killing as a way of repelling the reader from it. It isn't heroic. It's simple. And therein lies the horror.

Keith DouglasThis is another war poem, by another British soldier, from another war. And for me, its power comes from the way the poem's speaker demystifies the act of killing as a way of repelling the reader from it. It isn't heroic. It's simple. And therein lies the horror.

Here is a link to the poem.

A bit about the form of the poem, because it is important to its meaning. This poem rhymes, often with loose rhyme, but it does. The stanzas are five lines each, and the rhyme scheme is a-b-c-c-b-a.

Think of the rhyme scheme as a progression; it goes up, reaches the top, then goes back the way it came. An arc, perhaps. Or--a parabola. Bullets and shells travel in an arc. Because mass loses velocity over time and distance, all projectiles are launched upwards (even slightly, in the case of a rifle), because they will fall as they travel out towards their target.

So do balls. Children's balls. And so the poem begins: "Under the parabola of a ball..."

It's a simple transition for the poem's speaker to go from children's games to the game of killing a man during war. It makes the reader pause to think how difficult it should be. For me, the most memorable line in the poem is this:

"How easy it is to make a ghost."

In the final stanza, with its comparison of a human life to the image of the shadow of a mosquito, I find echoes of Shakespeare's Macbeth ("life is but a walking shadow..."). This is a beautifully crafted poem about a sobering subject. To add a layer of pathos to all this, Keith Douglas was himself killed in battle--at Normandy, following D-Day.

Keith DouglasThis is another war poem, by another British soldier, from another war. And for me, its power comes from the way the poem's speaker demystifies the act of killing as a way of repelling the reader from it. It isn't heroic. It's simple. And therein lies the horror.

Keith DouglasThis is another war poem, by another British soldier, from another war. And for me, its power comes from the way the poem's speaker demystifies the act of killing as a way of repelling the reader from it. It isn't heroic. It's simple. And therein lies the horror. Here is a link to the poem.

A bit about the form of the poem, because it is important to its meaning. This poem rhymes, often with loose rhyme, but it does. The stanzas are five lines each, and the rhyme scheme is a-b-c-c-b-a.

Think of the rhyme scheme as a progression; it goes up, reaches the top, then goes back the way it came. An arc, perhaps. Or--a parabola. Bullets and shells travel in an arc. Because mass loses velocity over time and distance, all projectiles are launched upwards (even slightly, in the case of a rifle), because they will fall as they travel out towards their target.

So do balls. Children's balls. And so the poem begins: "Under the parabola of a ball..."

It's a simple transition for the poem's speaker to go from children's games to the game of killing a man during war. It makes the reader pause to think how difficult it should be. For me, the most memorable line in the poem is this:

"How easy it is to make a ghost."

In the final stanza, with its comparison of a human life to the image of the shadow of a mosquito, I find echoes of Shakespeare's Macbeth ("life is but a walking shadow..."). This is a beautifully crafted poem about a sobering subject. To add a layer of pathos to all this, Keith Douglas was himself killed in battle--at Normandy, following D-Day.

Published on May 16, 2019 16:08

March 22, 2019

Some Poems Worth Your Time: “Dulce et Decorum est”--Wilfred Owen

Some Poems Worth Your Time: “Dulce et Decorum est”--Wilfred Owen

If you know Wilfred Owen’s poetry at all, it is probably for this poem, which confronts the idea

From Arlington Cemetery, Washington DC -- "Dulce..."that war is in any way romantic with the specter of a grisly death as a result of a chlorine gas attack. Part of the power of the poem no doubt comes from our knowledge that Owen himself died as a soldier, just before the end of World War I. It’s not just that he can critique those who never fought because he was there—he actually died there, and the poem speaks to us from beyond the grave (as this poem was only published after his death).

From Arlington Cemetery, Washington DC -- "Dulce..."that war is in any way romantic with the specter of a grisly death as a result of a chlorine gas attack. Part of the power of the poem no doubt comes from our knowledge that Owen himself died as a soldier, just before the end of World War I. It’s not just that he can critique those who never fought because he was there—he actually died there, and the poem speaks to us from beyond the grave (as this poem was only published after his death).Read the poem here.

The title comes from the Roman poet Horace, and it is the first part of the sentence, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.” How sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s country!

My experience says Owen's kind of cynicism is pretty common among soldiers. There is the thought that politicians and other would-be patriots send soldiers off to war, waving flags and shouting “hurrah,” but they leave the fighting to the likes of Owen. Of us.

In the movie Patton, when he is making his speech in front of the enormous American flag, Patton shows his knowledge of Horace’s words—and, like Owen, he refutes them. He tells his soldiers, “No bastard ever won a war dying for one’s country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for HIS country!” We soldiers know that we are the poor, dumb bastards who will do the dying.

When I was in Korea, it was common practice to stencil a motto of some sort on the windshield of one’s vehicle (my ride was a HMMWV—a “Humvee,” or in the commercial version, a Hummer). I asked my driver to stencil the title of this poem on the windshield, and so he did. DULCE ET DECORUM EST. In stenciled block letters.

It might not surprise you to learn that it bothered him. It bothered him because it was Latin. He didn’t know any Latin, and neither did any of his driver friends. And so it would have been confusing. Second, he didn’t know the poem. More confusion. And my explaining the context didn’t help, since he wasn’t comfortable with the cynicism.

“What do I tell people when they ask me what it means?” he asked me. It was a good question. It was an existential question, really. If this is what you think, then what are we doing here? To borrow from one of my favorite anti-war songs (“And the Band Played ‘Waltzing Matilda’”), “I ask myself the same question.”

“Tell them it says, ‘How sweet it is!’ in Latin,” I offered. He thought about it, and he decided it might work as an explanation.

And so we drove around, training and inspecting, with our motto on the windshield. He grew used to it. And I relished the inside joke.

Later, on one of our many training exercises, I pulled up to a big meeting at the headquarters tent, and I met another West Pointer, who had read Owen’s poem in his cadet days. He grinned when he saw it and completed the quotation (as Owen does in the final line of the poem, where he calls it “the old lie”—the motto on the chapel at Sandhurst, Britain’s officer training school.)

“Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori!” he cried. Yes, yes! I nodded. We no longer needed our West Point rings to know we were in the club. We shared this poem.

I saw him later, on another exercise. And this time, his vehicle had completed the motto: “PRO PATRIA MORI” it said. To die for one’s country.

Published on March 22, 2019 13:33

Poems Worth Your Time: “Dulce et Decorum est”--Wilfred Owen

Poems Worth Your Time: “Dulce et Decorum est”--Wilfred Owen

If you know Wilfred Owen’s poetry at all, it is probably for this poem, which confronts the idea

From Arlington Cemetery, Washington DC -- "Dulce..."that war is in any way romantic with the specter of a grisly death as a result of a chlorine gas attack. Part of the power of the poem no doubt comes from our knowledge that Owen himself died as a soldier, just before the end of World War I. It’s not just that he can critique those who never fought because he was there—he actually died there, and the poem speaks to us from beyond the grave (as this poem was only published after his death).

From Arlington Cemetery, Washington DC -- "Dulce..."that war is in any way romantic with the specter of a grisly death as a result of a chlorine gas attack. Part of the power of the poem no doubt comes from our knowledge that Owen himself died as a soldier, just before the end of World War I. It’s not just that he can critique those who never fought because he was there—he actually died there, and the poem speaks to us from beyond the grave (as this poem was only published after his death).Read the poem here.

The title comes from the Roman poet Horace, and it is the first part of the sentence, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.” How sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s country!

My experience says this kind of cynicism is pretty common among soldiers. There is the thought that politicians and other would-be patriots send soldiers off to war, waving flags and shouting “hurrah,” but they leave the fighting to the likes of Owen. Of us.

In the movie Patton, when he is making his speech in front of the enormous American flag, Patton shows his knowledge of Horace’s words—and, like Owen, he refutes them. He tells his soldiers, “No bastard ever won a war dying for one’s country. He won it by making the other poor dumb bastard die for HIS country!” We soldiers know that we are the poor, dumb bastards who will do the dying.

When I was in Korea, it was common practice to stencil a motto of some sort on the windshield of one’s vehicle (my ride was a HMMWV—a “Humvee,” or in the commercial version, a Hummer). I asked my driver to stencil the title of this poem on the windshield, and so he did. DULCE ET DECORUM EST. In stenciled block letters.

It might not surprise you to learn that it bothered him. It bothered him because it was Latin. He didn’t know any Latin, and neither did any of his driver friends. And so it would have been confusing. Second, he didn’t know the poem. More confusion. And my explaining the context didn’t help, since he wasn’t comfortable with the cynicism.

“What do I tell people when they ask me what it means?” he asked me. It was a good question. It was an existential question, really. If this is what you think, then what are we doing here? To borrow from one of my favorite anti-war songs (“And the Band Played ‘Waltzing Matilda’”), “I ask myself the same question.”

“Tell them it says, ‘How sweet it is!’ in Latin,” I offered. He thought about it, and he decided it might work as an explanation.

And so we drove around, training and inspecting, with our motto on the windshield. He grew used to it. And I relished the inside joke.

Later, on one of our many training exercises, I pulled up to a big meeting at the headquarters tent, and I met another West Pointer, who had read Owen’s poem in his cadet days. He grinned when he saw it and completed the quotation (as Owen does in the final line of the poem, where he calls it “the old lie”—the motto on the chapel at Sandhurst, Britain’s officer training school.)

“Dulce et decorum pro patria mori!” he cried. Yes, yes! I nodded. We no longer needed our West Point rings to know we were in the club. We shared this poem.

I saw him later, on another exercise. And this time, his vehicle had completed the motto: “PRO PATRIA MORI” it said. To die for one’s country.

Published on March 22, 2019 13:33

February 28, 2019

It's Alive!

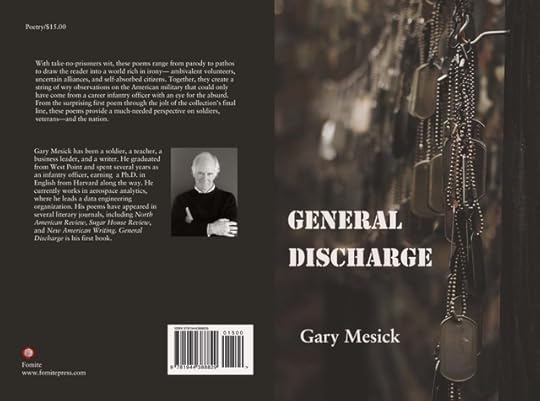

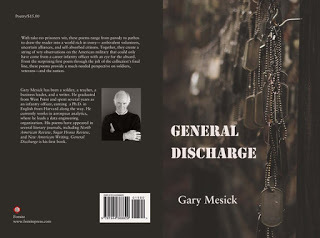

General Discharge is now in the world. And at this moment, I remember something I was told when I was on an army staff somewhere: Once you write a memo, you can't follow it around just so you can explain it to other people ("What I meant to say was..."). It has its own life.

General Discharge is now in the world. And at this moment, I remember something I was told when I was on an army staff somewhere: Once you write a memo, you can't follow it around just so you can explain it to other people ("What I meant to say was..."). It has its own life.As much as I might like to, I can't follow this book around. So I hope each of you will make it your own.

I do want to know what in it spoke to you (and I would love to know what it said). And I hope that this book is in some way useful to you on your journey, wherever it takes you.

Published on February 28, 2019 19:22

February 19, 2019

Embracing Rejection -- Part Three

Embracing Rejection -- Part Three

On the eve of General Discharge being published, I thought I would share the story of its finding its way into print.

I write poetry about a number of subjects, from nature, to books and movies, to personal recollections about childhood--and the military. After 9/11, I imagined that poetry from a military point of view might be of interest, since we were once again a nation at war. To paraphrase "The Big Short," I wasn't wrong. I was just early (which, as one of the book's/movie's characters retorts, is the same thing.). Most of the military poems I wrote remained unpublished. But others (including musings on nature, books and movies, and recollections of childhood) were picked up by journals from time to time. Still, I continued to write military-themed poems (because I had to).

I write poetry about a number of subjects, from nature, to books and movies, to personal recollections about childhood--and the military. After 9/11, I imagined that poetry from a military point of view might be of interest, since we were once again a nation at war. To paraphrase "The Big Short," I wasn't wrong. I was just early (which, as one of the book's/movie's characters retorts, is the same thing.). Most of the military poems I wrote remained unpublished. But others (including musings on nature, books and movies, and recollections of childhood) were picked up by journals from time to time. Still, I continued to write military-themed poems (because I had to).

By 2017, I had over two dozen poems in respectable literary journals. And so I thought I would see if I had enough for a book. I tried organizing the poems around a number of themes. But then, an interesting thing happened. In 2017, my military-themed poems found an audience. A number of them were published all at once. And so I thought that their time might have finally come, and that I might build a book around them.

Why did this happen? I don't know. My guess is that it had something to do with the 2016 election. And as people realized there were large swaths of the American population they had never met, some journal editors decided to introduce their readers to these other people through my poems. I know the poems themselves hadn't changed. And one of them ("Compline, Camp Casey") had been around--and submitted to journals--for over 25 years before being published last summer.

By August of 2018, I had a book that I felt good about. So I sent it out to a few small publishers. One of them was Blackstone Books. Within a month, I heard back from Larry Moore, the publisher--and it was, as I had come to expect, a rejection letter.

But it was the kindest, the best rejection letter I have ever received. He thanked me, of course, and he said that he really liked the book. He even quoted lines of my poems to me (which I took as high praise). And then he let me down softly, saying that as much as he liked it, it didn't make his cut. But then, in act of generosity, he suggested I contact Fomite Press, as Broadstone and Fomite share an author in common, and he thought my work might be a better fit there.

This was a rejection truly worth embracing.

And so I contacted Marc Estrin, and I sent him a sample of the book. He liked what he saw, and he asked to see the whole book. And we made a match.

I am very pleased with the whole process of working with Marc Estrin and Donna Bister at Fomite. I think Larry was right that this was where my book belonged. But it would have taken me much longer to find them (if I ever did) without the act of kindness and the sense of belonging to a community shown by Larry Moore at Broadstone. Thank you!

On the eve of General Discharge being published, I thought I would share the story of its finding its way into print.

I write poetry about a number of subjects, from nature, to books and movies, to personal recollections about childhood--and the military. After 9/11, I imagined that poetry from a military point of view might be of interest, since we were once again a nation at war. To paraphrase "The Big Short," I wasn't wrong. I was just early (which, as one of the book's/movie's characters retorts, is the same thing.). Most of the military poems I wrote remained unpublished. But others (including musings on nature, books and movies, and recollections of childhood) were picked up by journals from time to time. Still, I continued to write military-themed poems (because I had to).

I write poetry about a number of subjects, from nature, to books and movies, to personal recollections about childhood--and the military. After 9/11, I imagined that poetry from a military point of view might be of interest, since we were once again a nation at war. To paraphrase "The Big Short," I wasn't wrong. I was just early (which, as one of the book's/movie's characters retorts, is the same thing.). Most of the military poems I wrote remained unpublished. But others (including musings on nature, books and movies, and recollections of childhood) were picked up by journals from time to time. Still, I continued to write military-themed poems (because I had to).By 2017, I had over two dozen poems in respectable literary journals. And so I thought I would see if I had enough for a book. I tried organizing the poems around a number of themes. But then, an interesting thing happened. In 2017, my military-themed poems found an audience. A number of them were published all at once. And so I thought that their time might have finally come, and that I might build a book around them.

Why did this happen? I don't know. My guess is that it had something to do with the 2016 election. And as people realized there were large swaths of the American population they had never met, some journal editors decided to introduce their readers to these other people through my poems. I know the poems themselves hadn't changed. And one of them ("Compline, Camp Casey") had been around--and submitted to journals--for over 25 years before being published last summer.

By August of 2018, I had a book that I felt good about. So I sent it out to a few small publishers. One of them was Blackstone Books. Within a month, I heard back from Larry Moore, the publisher--and it was, as I had come to expect, a rejection letter.

But it was the kindest, the best rejection letter I have ever received. He thanked me, of course, and he said that he really liked the book. He even quoted lines of my poems to me (which I took as high praise). And then he let me down softly, saying that as much as he liked it, it didn't make his cut. But then, in act of generosity, he suggested I contact Fomite Press, as Broadstone and Fomite share an author in common, and he thought my work might be a better fit there.

This was a rejection truly worth embracing.

And so I contacted Marc Estrin, and I sent him a sample of the book. He liked what he saw, and he asked to see the whole book. And we made a match.

I am very pleased with the whole process of working with Marc Estrin and Donna Bister at Fomite. I think Larry was right that this was where my book belonged. But it would have taken me much longer to find them (if I ever did) without the act of kindness and the sense of belonging to a community shown by Larry Moore at Broadstone. Thank you!

Published on February 19, 2019 08:53

January 23, 2019

First Look at the cover of General Discharge

Published on January 23, 2019 14:32

January 8, 2019

The new book, "General Discharge," continues apace. I hav...

The new book, "General Discharge," continues apace. I have the first proofs, and I have begun looking through them, making sure things look as they should. At first glance, it looks to be in good shape.

I expect the book to be out near the end of March.

I expect the book to be out near the end of March.

Published on January 08, 2019 07:53

December 3, 2018

Some Poems Worth Your Time: Lessons of the War--Henry Reed

Some Poems Worth Your Time: Lessons of the War--Henry Reed

If you recognize Henry Reed, it is likely for "The Naming of Parts." But this is just one of six in a poem sequence called "Lessons of the War." Still, it's a good place to start.

Here is a link to the six-poem sequence. Do yourself a favor and read at least the first sequence (the aforementioned "The Naming of Parts").

"The Naming of Parts" is an exchange between a British sergeant and the speaker--though the speaker's words are likely only thought, rather than spoken. Reed gets the sergeant's overly officious and slightly clueless diction just right, so that we share (and delight) in the speaker's recognition that the sergeant doesn't quite understand everything he is trying to teach. And meanwhile, the speaker reveals his ambivalence toward the service he has been called to give, which invites others to identify with him--by "others," I mean "others not in uniform."

But the wonderful thing for me about this poem is that it appeals to people IN uniform. I found it and fell in love with it as an army officer.

In "The Naming of Parts," it's clear the recruit-speaker is not completely committed to the military way of life. But when you read the rest of the poems in the sequence, you see his sympathy for the cause emerge from time to time. In that way, the poems resemble Herman Wouk's "The Caine Mutiny," where Captain Queeg has clearly come unhinged--and yet we can't dismiss him entirely, because he was there to serve his country when no one else was.

The poem has always been a favorite of mine--part laughing at those who I imagine I know better than, part laughing at myself, part seeing the nobility even in the imperfect execution of service.

By the way, I have decided on a phrase from one of the other poems in this sequence ("Unarmed Combat") for the epigraph to my book "General Discharge."

If you recognize Henry Reed, it is likely for "The Naming of Parts." But this is just one of six in a poem sequence called "Lessons of the War." Still, it's a good place to start.

Here is a link to the six-poem sequence. Do yourself a favor and read at least the first sequence (the aforementioned "The Naming of Parts").

"The Naming of Parts" is an exchange between a British sergeant and the speaker--though the speaker's words are likely only thought, rather than spoken. Reed gets the sergeant's overly officious and slightly clueless diction just right, so that we share (and delight) in the speaker's recognition that the sergeant doesn't quite understand everything he is trying to teach. And meanwhile, the speaker reveals his ambivalence toward the service he has been called to give, which invites others to identify with him--by "others," I mean "others not in uniform."

But the wonderful thing for me about this poem is that it appeals to people IN uniform. I found it and fell in love with it as an army officer.

In "The Naming of Parts," it's clear the recruit-speaker is not completely committed to the military way of life. But when you read the rest of the poems in the sequence, you see his sympathy for the cause emerge from time to time. In that way, the poems resemble Herman Wouk's "The Caine Mutiny," where Captain Queeg has clearly come unhinged--and yet we can't dismiss him entirely, because he was there to serve his country when no one else was.

The poem has always been a favorite of mine--part laughing at those who I imagine I know better than, part laughing at myself, part seeing the nobility even in the imperfect execution of service.

By the way, I have decided on a phrase from one of the other poems in this sequence ("Unarmed Combat") for the epigraph to my book "General Discharge."

Published on December 03, 2018 13:50

December 1, 2018

Some Poems Worth Your Time: The Cool Web--Robert Graves

Some Poems Worth Your Time: The Cool Web--Robert Graves

Robert Graves may be best known to contemporary readers for his "I, Claudius" novels (I, Claudius, and Claudius the God)--not because they have actually read them, but because they were made into a well-known BBC miniseries. And some may actually know him for his World War I memoir, Goodbye to All That--again, not because they have read it, but because Joan Didion appropriated the title of Graves's memoir for her seminal essay/memoir about 1960s New York from her collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem (the title lifted from the Yeats poem. Didion only appropriated from the best!).

But Graves was also a poet, and if he had only written this one poem, his name--as well as this poem--would be worth committing to memory.

Here is a link to the poem.

Many people who read this poem try to excuse the first line "Children are dumb," likely because it seems like a cruel thing to say. They explain that Graves means "mute" not "stupid." I'm not so sure. I think we need to allow for both when we read this. The poem is shocking throughout, so why not allow that it is shocking from the first line? Besides, it's not as if Graves would have been unaware of the dual meaning. It's been part of the English language longer than there has been an English language ("dumb" meant "stupid in Old High German and the German languages that followed) and it was in common use in the "stupid" sense by the late 18th or early 19th century--a century or two before Graves's poem.

The poem is about what we gain and what we lose when we put language between us and our experience. Children learn how to do this as they grow up. When they are young, they don't have the words--are "dumb"--to describe beauty, or fear, or war. But they also don't know--are ignorant as to how--are "dumb" in the other sense.

Our language allows us to describe these things, but at a loss. Nothing is as magnificent, or as terrifying, once we put it into words. And so we lose something in gaining speech.

What I love about the poem is that it isn't nostalgic for some lost childhood. Sure, we lose the direct access to our experience once we water it down with language. But the poem suggests that it's a matter of survival. As Jack Nicholson's character says in A Few Good Men, "You can't handle the truth!!" And so we can't. It would drive us mad to confront life without a filter, without the distance language provides us. So pick your poison: life by the drop and die young; or live a more tedious, but longer and more cultivated existence.

And there is the matter of the title. The poet says it is the "cool web of language winds us in." We are caught in its web like a spider's prey. And it is just a matter of time before language devours us. But this is a Hobson's choice (a choice without a choice): either we succumb to language or we go insane, which the poet compares to drowning--which is just another way of being swallowed up. (nb--language may water down raw experience, but Graves uses water to represent that raw experience. I don't know why.)

It's impossible for me--as it might be for you--to think of this poem's title without also thinking of E.B. White's Charlotte's Web--another memorable work about the web of language--and death. Just remember--Graves got there first!

Robert Graves may be best known to contemporary readers for his "I, Claudius" novels (I, Claudius, and Claudius the God)--not because they have actually read them, but because they were made into a well-known BBC miniseries. And some may actually know him for his World War I memoir, Goodbye to All That--again, not because they have read it, but because Joan Didion appropriated the title of Graves's memoir for her seminal essay/memoir about 1960s New York from her collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem (the title lifted from the Yeats poem. Didion only appropriated from the best!).

But Graves was also a poet, and if he had only written this one poem, his name--as well as this poem--would be worth committing to memory.

Here is a link to the poem.

Many people who read this poem try to excuse the first line "Children are dumb," likely because it seems like a cruel thing to say. They explain that Graves means "mute" not "stupid." I'm not so sure. I think we need to allow for both when we read this. The poem is shocking throughout, so why not allow that it is shocking from the first line? Besides, it's not as if Graves would have been unaware of the dual meaning. It's been part of the English language longer than there has been an English language ("dumb" meant "stupid in Old High German and the German languages that followed) and it was in common use in the "stupid" sense by the late 18th or early 19th century--a century or two before Graves's poem.

The poem is about what we gain and what we lose when we put language between us and our experience. Children learn how to do this as they grow up. When they are young, they don't have the words--are "dumb"--to describe beauty, or fear, or war. But they also don't know--are ignorant as to how--are "dumb" in the other sense.

Our language allows us to describe these things, but at a loss. Nothing is as magnificent, or as terrifying, once we put it into words. And so we lose something in gaining speech.

What I love about the poem is that it isn't nostalgic for some lost childhood. Sure, we lose the direct access to our experience once we water it down with language. But the poem suggests that it's a matter of survival. As Jack Nicholson's character says in A Few Good Men, "You can't handle the truth!!" And so we can't. It would drive us mad to confront life without a filter, without the distance language provides us. So pick your poison: life by the drop and die young; or live a more tedious, but longer and more cultivated existence.

And there is the matter of the title. The poet says it is the "cool web of language winds us in." We are caught in its web like a spider's prey. And it is just a matter of time before language devours us. But this is a Hobson's choice (a choice without a choice): either we succumb to language or we go insane, which the poet compares to drowning--which is just another way of being swallowed up. (nb--language may water down raw experience, but Graves uses water to represent that raw experience. I don't know why.)

It's impossible for me--as it might be for you--to think of this poem's title without also thinking of E.B. White's Charlotte's Web--another memorable work about the web of language--and death. Just remember--Graves got there first!

Published on December 01, 2018 17:29