Alexander Hellene's Blog, page 2

April 4, 2021

Happy Easter!

To all my Western Christian friend, happy Easter! He is Risen!

April 1, 2021

Order of Operations

If you’re going to be an independent writer outside of the big five traditional publishing houses, you have to wear many hats, not just your authorial one. Yes, this means marketing and promotion and handling artwork and all of that. If this isn’t for you, then keep sending query letters to agents, I guess.

Anyway, one question that I grappled with early on when starting this crazy adventure was whether to publish as soon as books are written and edited and polished and so on, or wait until multiple books were already written, series or not, and carpet bomb the world with them.

Many intelligent and successful writers recommended the second path to me: build up a backlog of ready-to-publish novels and then blitz the reading public. I, however, did not. There are a few reasons for this:

I’m impatient. I get very excited about what I’m working on at the time, and then when it’s done, I move on to the next thing and get very excited about that. Therefore, I like to finish one project conclusively before starting another.I can’t multitask. I tried writing two books at the same time in 2020. My goal was to publish them both by summer. That turned into publishing both in the calendar year 2020. It ended up being publishing one right after Thanksgiving and the other right before New Year’s to say that I technically accomplished my goal. I don’t think I’ll ever write two books at the same time again.It’s psychological. Publishing my first book in 2018 was huge. It elevated me from that mental “wannabe/aspiring writer” label way too many of us attach to ourselves and made it feel “official.” The next three books came a lot easier.It’s motivating. I don’t think I’d have as much drive to write and publish if I didn’t have an incomplete series out there. While I had it outlined and I knew how I wanted the entire series to go and, more importantly, to end, I knew if I tried writing all three before publishing I’d let perfectionism be my enemy. Instead, getting book one out there and–shocker!–having fans keep asking me when book two would be out really made me want to keep writing even more.As writers, we make promises to our readers. If you want to keep being a writer that people want to read, you must keep those promises. I find that publishing as I go helps me keep that fire alive. As always, though, do what works for you. For example, maybe you have a lot more time for writing than I do and you can crank out two, three, or more books in a matter of months. If so, go for it. Don’t let some guy on the intent stop you.

“What if I die before finishing my books?”

I don’t know! I can’t see into the future. Eat healthy and exercise, I guess. And don’t be lazy (you know the writer I’m writing about; for real, I’ve never seen a writer who hates writing as much as that guy. And no, this isn’t an oblique reference to Robert Jordan. He had everything ready to go and wrote like a madman at an impressive pace until he was slowed and ultimately taken by a rare illness. Jordan is a personal inspiration to me).

And if you do die before finishing your books? Join the club. Everybody dies before they tell every story that is their soul.

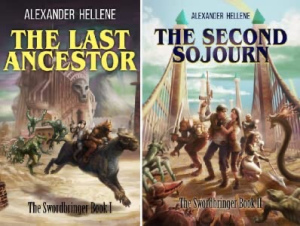

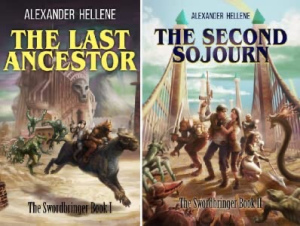

The fruits of my labors: buy them here!

March 30, 2021

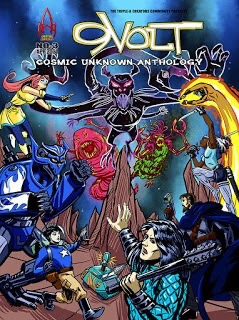

Signal Boost: 9Volt Comics: Cosmic Unknown Anthology

Yeah! It’s been a long time coming, but the fine folks at the Triple-A Creators’ Community are out with another issue of their 9Volt comic anthology: Cosmic Unknown:

Science Fiction and Fantasy! What could possible be a better combination? Here are NINE STORIES of spacefaring, futuristic cosmic magical mystery featuring action, adventure, and awesomeness. Featuring ArtAnon Studios, Dale A, Jim Stanislawski, Daniel McGuiness, Robin Taylor, Evan Hill, Jake Tvister, and Peter Seckler

You might recognize some of these names, including my friend ArtAnon who did character art for The Last Ancestor and the maps for my Swordbringer books. Worth supporting not only because these are good people, but because the comic is fantastic.

Snag it here!

And snag my books here!

March 29, 2021

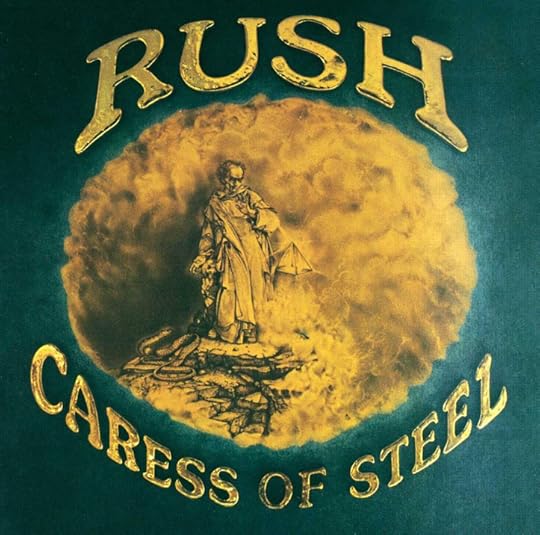

Music Review: Rush, Caress of Steel (1975)

Release Date: September 24, 1975

Personnel:

Geddy Lee – bass and vocalsAlex Lifeson – 6 and 12 string electric and acoustic guitars, classical guitar, steel guitarNeil Peart – percussionProduced By: Rush and Terry Brown

Recorded At: Toronto Sound Studios, Toronto, Canada

Singles:

“Return of the Prince”Released: 1975“Lakeside Park”

Released: 1975

Chart Position and Awards:

Billboard Pop Albums: #148Music: Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson. Lyrics: Neal Peart, except “Panacea” and “Bacchus Plateau” – Music: Geddy Lee. Lyrics: Neil Peart.

1975 was a busy year for Rush. After touring throughout the better part of 1974 and stopping only to quickly record their second album, Fly By Night, before 1975 rolled around, they continued to tour and build their audience show by show. They’d play anywhere and open for anyone, sliding into relatively forgotten nooks and crannies all over the United States and Canada to win over converts to their heavy, frenetic, quirky sound.

Interestingly, the above show from June 25, 1975, from the Fly By Night tour is the show the Caress of Steel band photos are taken from.

But the boys were workaholics. It seems that Neil joining the band in mid-1974 had given them a shot in the arm. Although it had only been a few months since Fly By Night‘s release, they kept writing new songs and lyrics, coming up with new concepts in the vein of the previous album’s lengthy fantasy-prog epic “By-Tor and the Snow Dog” and even “Rivendell,” at least subject-matter wise (J.R.R. Tolkien), and were dying to return to the studio. So in July and August of 1975, Rush once again decamped to Toronto Sound Studios to record Caress of Steel.

Progressive rock was the name of the game, with an emphasis on the “rock.” Rush was always an interesting animal in the prog world, because whereas lots of bands like Genesis and Yes and King Crimson and ELP were very much influenced by classical music and jazz, Rush was influenced by British blues rock and early heavy metal. So while the music on Caress of Steel was conceptually lofty, and even delicate at times, the bulk of the sonic proceedings were designed to make you bang your head.

Neil has had more time with the band now, and their musical and personal bonds had been road-forged, their chops honed to a razor sharp edge reflected in the continuing confidence and swagger in each band member’s playing. Geddy’s bass lines swoop and soar and percolate and his growly, treble-heavy tone is in sharp contrast to his high-pitched wailing vocals. Alex Lifeson’s guitars bludgeon the listener with thick power chords one moment, delicate arpeggios and passages the next, and all sorts of blistering solos to make Eric Clapton wet his pants . . . and yet he also incorporates more jazzy and soulful elements into his playing.

And what more can be said about Neil Peart? The guy was a monster, and here he continues his Keith Moon as filtered through a jazz-fusion lens with more intricate and lyrical drum parts and fills–his work not the toms is particularly notable–while his lyrics tackle a more diverse range of subject matter than the band was used to. Caress of Steel is notable as being the first album Peart wrote all the lyrics for. Oh, and he also grew a mustache.

Gone are the songs about life on the road, or the wild world of rock and roll. Instead, we delve into history, myth and legend, childhood memories, and . . . well . . . losing one’s hair:

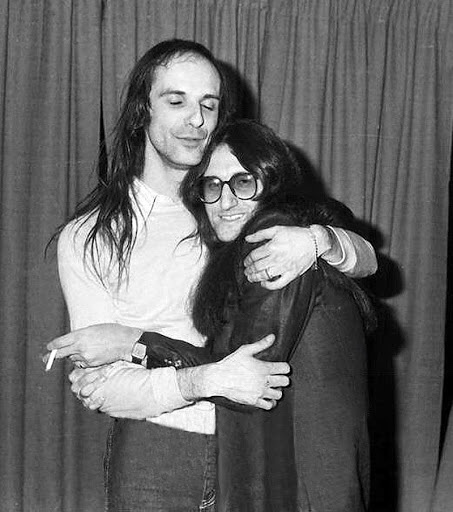

“I Think I’m Going Bald” was written for Kim Mitchell, who at the time was the frontman of the band Max Webster and a close friend of the band.

Geddy Lee with Kim Mitchell who was indeed going bald.

Geddy Lee with Kim Mitchell who was indeed going bald.And yet there is an alternative explanation for the origin of this song:

We were touring a lot with KISS in those days and they had a song called “Goin’ Blind.” So we were kind of taking the piss out of that title by just coming up with this . . . Pratt [Neil Peart] came up with this line, “I think I’m going bald,” because Alex is always worried about losing his hair. Even when he was not losing his hair, he was obsessed with the fact that he might lose his hair. So he would try all kinds of ingredients to put on his scalp. And I think it just got Neil thinking about aging, even though we weren’t aging yet and had no right to talk about that stuff yet. It would be much more appropriate now.

— Geddy Lee, Contents Under Pressure (2004)

Believe what you will. I myself think both are likely true.

Sonically, I have read much criticism that Caress of Steel sounds muddy. Not to these ears! Maybe the original vinyl left something to be desired, but this album sounds raw, powerful, and punchy with the clear production values we’ve come to expect from Terry Brown. Every instrument is audible and sounds great, though I could do with a bit more hi-hat, and Geddy’s vocals are never overpowered nor overpowering. And there are enough cool little touches, particularly on the two prog-epics “The Necromancer” and “The Fountain of Lamneth” that portend the “movie for your ears” approach Rush would take on subsequent releases.

So the important question remains: are the actual songs any good? Does Caress of Steel deserve its reputation as a lackluster outing, the black sheep of Rush’s early days? Do you think I’d spoil the answer for you before we even get to the songs? Heaven forbid!

“Bastille Day” — A stone-cold classic, and yet another scorching opener to a Rush album. Somehow, Geddy and Alex turned Neil’s lyrics about the French Revolution, of all things, into a fantastic head-banger. An instantly classic opening guitar line is punctuated by iconic bass-and-drum flourishes of a type the band will revisit as far forward as 2012’s Clockwork Angels. The aggressive main chord progression is likewise one of Rush’s most memorable, while the choruses are majestic and powerful. No wonder “Bastille Day” was their concert opener for a good stretch of the 1970s. Rush demonstrates right out of Caress of Steel‘s gate their modus operandi of melding the orchestration and tricky rhythmic complexity of prog with the bombast of their hard rock and heavy metal roots. Listen closely to the instrumental section–the band never takes the easy route. You can instantly hear how Neil’s lyrics change the way Geddy sings; a lot of these couplets and stanzas are a mouthful. Outstanding song. 9 out of 10.

“I Think I’m Going Bald” — A fun, goofy blues rock boogie-woogie number that harkens back to the first album, although there’s enough variety and uniqueness to elevate the song above typical butt-rock. Absolutely savage guitar solos by Alex. “I Think I’m Going Bald” doesn’t push the band forward, though the lyrics are surprisingly poignant while displaying the band’s supposedly absent sense of humor. A decent tune that was played live on the Caress of Steel tour but subsequently dropped due to fan disinterest. 7 out of 10.

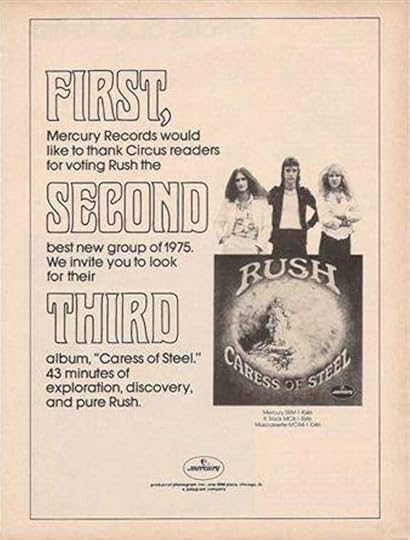

“Lakeside Park” — This is tough, because I like this song quite a bit, but it’s a good song and not a great song. It has very poignant lyrics about a favorite place in Neil Peart’s childhood, and I appreciate Rush’s emerging stylistic diversity and ability to play at a quieter dynamic. There is some very pretty guitar playing, a wonderfully syncopated melodic bass lines, and some great lyrical drumming–Neil’s toms sound fantastic. So “Lakeside Park” demonstrates Rush’s depth, and remained a fan favorite, but it just lacks the certain spark that the previous album’s pop stand-out “Fly By Night” had.

A big influence on me when I was starting out was Pete Townshend and he was such a consummate rhythm guitarist. I gravitated to Jimmy Page, Hendrix, and Clapton for soloing, but there was something about the way Townshend strummed the guitar that was very acoustic-like. “Lakeside Park” is an example of that. It was written on an acoustic guitar so that strumming came naturally. It translates to an electric well.

— Alex Lifeson, Guitar Player, November 2012

I’d love to rate is higher, but I can’t. This song was not Geddy’s favorite at all, and while I think it is much better than Geddy does, it’s missing that ineffable quality, that “wow” factor. 7 out of 10.

I can’t go back beyond 2112 really, because that starts to get a bit hairy for me, and if I hear “Lakeside Park” on the radio I cringe. What a lousy song! Still, I don’t regret anything that I’ve done!

— Geddy Lee, RAW, October 27, 1993

This isn’t in the album’s liner notes; I just found it on-line.

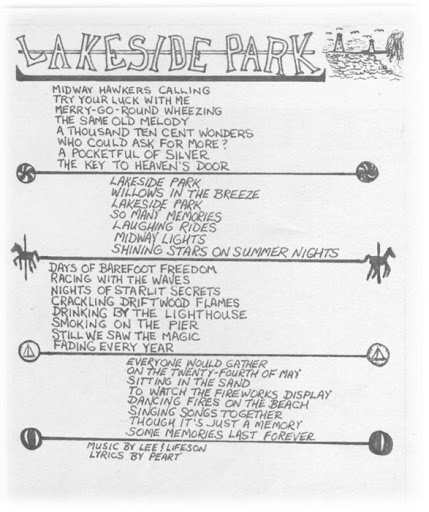

This isn’t in the album’s liner notes; I just found it on-line.I. Into Darkness

II. Under the Shadow

III. Return of the Prince

Now we’re getting to the really fun stuff! “The Necromancer” is a three-part fantasy-based prog epic, complete with spoken word introductions to each movement by Neil Ellwood Peart himself. Loosely based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s mythology, “The Necromancer” tells the story of “three men of Willowdale” (the Toronto suburb from which Geddy and Alex hail) traveling to defeat the titular baddie and free the land from his evil reign. The Necromancer broods in his tower, keeping an eye on all the world with his “evil prism eye”; and yes, that is the Necromancer on the album cover. Musically, “The Necromancer” shows Rush stretching out and enjoying the fantasy-prog style they hinted at in “By-Tor and the Snow Dog“; in fact, Prince By-Tor is the hero of this one. Musically, “The Necromancer” showcases what Rush were all about in the mid-70s. Part I is a slow, dark, and brooding, with some clever backwards guitar and a lugubrious pace that highlights the enervating blight the Necromancer has cast over the land. Part II begins with some phased drums a very mean riff before shifting into a straight up, Cream-inspired inspired power-trio freak-out. This is about as freewheeling as Rush ever got, and it’s quite exhilarating. Part III brings it home, with a pretty, triumphant melody resplendent with ringing guitars and some great bass work.

“The Necromancer” is more fun than mind blowing, and the band clearly enjoyed it enough to keep it in their concert reportorial up to and including the Permanent Waves tour. This is Rush pushing forward into new sonic and conceptual territory without taking themselves too seriously–that would come in the next track. 8 out of 10.

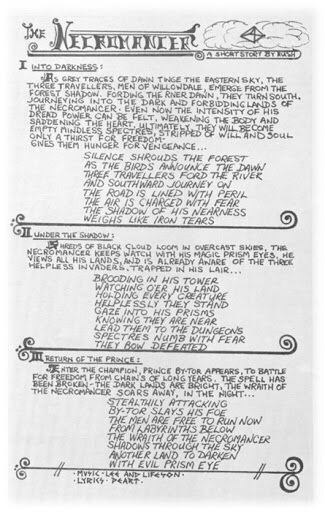

I. In the Valley

II. Didacts and Narpets

III. No One At the Bridge

IV. Panacea

V. Bacchus Plateau

VI. The Fountain

Rush’s first 20-minute prog epic, and this one is far more philosophical and serous than “The Necromancer.”

The idea [for “The Fountain Of Lamneth”] originally came from a time when I was driving from the top of a mountain to the bottom and, seeing the lights of the city beneath me, I got to thinking, “What would life be like if you could only measure your position as a person by the level at which you lived up the side of a mountain?” I got to drawing relations, seeing lots of comparisons in this metaphor and eventually put down a rough sketch of the six different parts I thought there would be to such a quest. It was really naïve, I admit that now, it was a ridiculous thing, like writing a thesis on metaphysics or something. But at the time it felt right, what can I say, we did it and we really enjoyed it.

— Neil Peart, Sounds, July 16, 1977

“The Fountain of Lamneth” shows Rush trying to create a cinematic piece of music and nearly pulling it off. Each of the song’s six movements have its own musical themes that build on Neil’s lyrical ones, and while the stone-faced seriousness might be a bit too goofy for some, persistent listeners who can put aside their own smirking irony will find a lot to love here. Unlike later Rush epics, the themes here don’t overlap and are are discrete compositions, although the last movement provide some nice symmetry by reprising the first; this theme alone would make a fine song, and wouldn’t sound out of place on later albums like A Farewell to Kings and Hemispheres. Lyrically, “The Fountain of Lamneth” chronicles a young man’s birth, desire to venture beyond the his home to the faraway mountains that tantalized him in his youth, and the adventures and lessons he learns along the journey. It’s vaguely inspired by Greek mythology such as The Odyssey with references to sirens, chemical stupor on the Bacchus Plateau that calls to mind the land of the Lotus eaters, and the lure of love as detailed in the oft-derided “Panacea,” where our nameless hero nearly puts aside wanderlust aside in favor of a more carnal type.

Musically, the pieces are quite good. “The Valley” has a haunting, exciting theme with the band milking the dynamic shifts to great effect. “Didacts and Narpets” is a short drum solo with some nearly incomprehensible screaming. Taking place after a shipwreck, “No One at the Bridge” features the sounds of waves lapping and appropriately seasick guitar arpeggios with an emotional guitar solo. “Panacea” isn’t really as bad as advertised, a jazzy ballad with nice chiming guitar harmonics in the chorus, though admittedly cheesy lyrics. “Bacchus Plateau” is a somber, major-key rumination on the stupefying powers of wine; I especially like Alex’s little finger twiddling flourishes and classy solo. “The Fountain” closes things out, with the lyrical denouement and a dramatic crescendo that will give you chills.

The band and crew claim this was never played live, yet one fan recounts a gig in Atlanta where Rush played nearly the entire suite. As only one incomplete recording from the Caress of Steel tour exists (see below), and there are no other surviving set lists, this is impossible to corroborate, but one wonders if the band, near the end of a miserable tour, decided to blow off some steam by playing “The Fountain of Lamneth” just for the hell of it.

On the whole, this is enjoyable song, a bit goofy and philosophically sophomoric, but it pushed the band forward. The fact remains that without “The Fountain of Lamneth,” there’d be no “2112” and everything else that came after. 8 out of 10.

Final Rating: 39/50 = .78 x 100 = 78

This rating fairly summarizes my thoughts on Caress of Steel. I might be in the minority, but I do like it more than Fly By Night. Caress of Steel is more original, more unique, and more fully realized. It is the first time you can’t describe a Rush song by saying it sounds like someone else, and where the band sounds like its own beast entirely.

Sadly, the album did not sell, moving far fewer units than Fly By Night despite the band’s–and the record company’s–high hopes. This, in conjunction with the poorly attended tour nicknamed the “Down the Tubes Tour” by Rush and crew, left uncertainty as to the band’s future. The only chronicle of this tour is a relatively poor quality 8 mm video that gives a tantalizing glimpse into this relative black hole of obscurity in an otherwise heavily chronicled band’s touring history:

Alas, as you will hear, no “The Fountain of Lamneth.”

The critics, predictably, weren’t thrilled with Caress of Steel. Some of these reviews are pretty brutal, with a lot of scorn heaped upon Peart’s lyrics while simultaneously praising Rush’s skill as performers.

Things were looking grim for Geddy, Alex, and Neil. Their new direction was not a hit with fans or critics. They were being slagged with the labels “pretentious” and “self-indulgent,” the kiss-of-death in the status-hungry, cool-chasing world of rock. Rush were being leaned on heavily by their record company to go back to a more basic sound and lyrical direction as on their debut and parts of Fly By Night.

Their management was able to convince the executives that Rush’s next album would be absolutely nothing like the prog-rock flights-of-fancy contained on Caress of Steel. Yes sir, back to basics, nothing philosophical or multi-part or any of that . . . right?

Well, if you know anything about Rush already, you know how that worked out. But even though you know this story has a happy ending, it’s still a lot of fun listening to how they got there. See you in the future in the year 2112 . . .

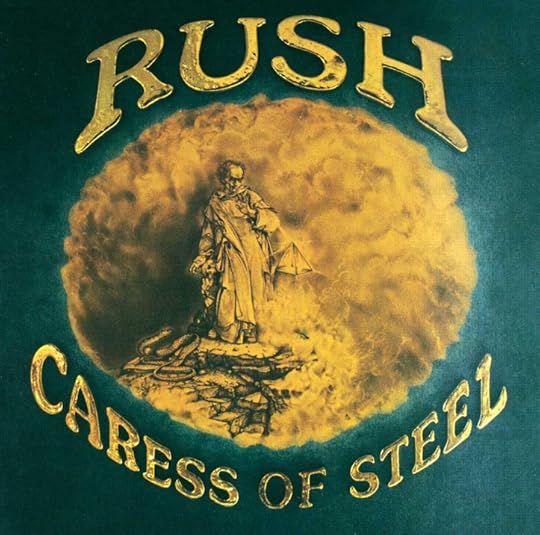

THE COVER

Designed by: Hugh Syme

Enter Canadian artist and musician Hugh Syme, who would be with Rush until the very end. For his first assignment, Syme was tasked with designing an appropriately epic wrapper for the music contained in Caress of Steel, and in my opinion he pulled it off!

Hugh Syme

Hugh SymeAlmost.

I mean, the cover clearly depicts the Necromancer brooding in his tower and staring into his evil prism eye. It’s a nice, clean, and mystical image that likely inspired a lot of pot-addled ruminations back in the day. But that color . . .

From Ultimate Classic Rock:

Syme’s first Rush project was Caress of Steel, which features a wizard-like character flanked by a coiled snake and mysterious triangle. It was a pivotal career moment, though he’s not especially fond of the image today — partly, he says, because the record company’s last-minute alterations. “I was a huge [M.C. Escher] fan,” he told UCR. “My original drawings were in pencil: clean, monochromatic, simple homages to Escher. But when the record label got ahold of these, they thought it wasn’t rock ‘n’ roll enough, so they added this chromium lettering and swung the tint of the whole image over to a brown sepia tone — none of which was requested or under my purview at the time.”

More:

As Rush’s art director since 1975, Hugh Syme designed some of the prog-rock band’s signature images: the glowing Red Star of the Solar Federation that adorns 2112, the visual puns of Moving Pictures, the scene of cheerful destruction on Permanent Waves.

But in retrospect, he isn’t completely satisfied with his work on Caress of Steel, the first of their numerous collaborations. Mostly, he says, because the record company made some last-minute alterations to his image, which shows a wizard-like character flanked by a coiled snake and mysterious triangle.

“I was a huge [M.C. Escher] fan,” Syme tells Ultimate Classic Rock. “My original drawings were in pencil: clean, monochromatic, simple homages to Escher. But when the record label got ahold of these, they thought it wasn’t rock and roll enough, so they added this chromium lettering and swung the tint of the whole image over to a brown sepia tone — none of which was requested or under my purview at the time.”

But there was one positive to the annoying interference: future creative control.

“When the band said, ‘What happened?,’ I said, ‘I don’t know,'” he adds. “That began the premise that they would consider most A&R people attending their sessions — and, more so, their comments — as unwelcome. Because they weren’t interested. And when they realized that other people were meddling in the process when it came to my art, they said, ‘Don’t listen to anyone. We’re talking to you directly.’ That set up a feature in my life.”

Looking back, Syme’s supernatural image is a fitting match for Caress of the Steel, Rush’s first full-blown foray into prog. The artist doesn’t count it among his finest covers, but he realizes it “served its purpose.”

“That album worked out well. I don’t look back fondly on the outcome, but that’s OK,” he says. “It was more just me being indulgent — art directors are pretty selfish. We do what we want to do, and what a gift it was to work with a band like Rush. They — excuse the quote — allowed that deviation from any norms because that’s what they aspired to do themselves as artists.”

Me? I like it! I’m not a fan of the lettering, and the color certainly does not scream “steel,” but the picture is solid and it really fits the music. You know what you’re getting into when you buy this and put it on your turntable or CD player or whatever. It’s certainly not one of Rush’s most iconic or recognizable covers among the general music-loving public, but it certainly is among the fans, ugly sepia tone and all.

Cover Rating: 6

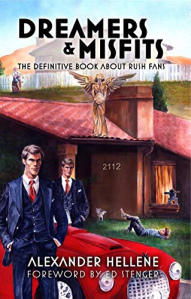

Read about Caress of Steel and other Rush albums beloved by the fans in my book Dreamers & Misfits, the only comprehensive survey of Rush fandom. Buy it here! The cover is also by a Canadian artist and musician.

March 28, 2021

Way Behind

I know, I know, I know–I’m behind on posts, behind on comments, behind on everything. I’ll make it up to you, I promise. And I’ll delete this later.

This free entertainment ain’t free, ya know!

God bless you all!

March 25, 2021

Money Isn’t Culture

Today we commemorate the Theotokos, the Ever-Virgin Mary, the Unwedded Bride, who received word from the Archangel Gabriel that she would bear God into the world. It’s an important church holiday for all Christians.

But there’s another, ethnic, component important to Greeks and those of Greek descent: March 25, 1821 is considered Greek Independence Day, the day when, according to the stories, Metropolitan Germanos of Patras raised the banner of the cross at the Monastery of Agia Lavra near Achaea, kickstarting the revolution against 400 years of Turkish oppression. Of course, leaders like Alexander Ypsilantis had been fomenting revolution against the Ottomans for some time before the Metropolitan’s fateful actions. The point is, the Annunciation was an important date chosen for a reason: the Greek revolutionaries recognized that their Christian heritage was vital to their well-being, that their ancestors left the worship of the Olympians for the One True God for a reason, and that only with divine providence could they throw off the shackles of oppression by the heathen Turks.

Of course, those who are not Christian will disagree with this characterization, but most cultures throughout world history can surely recognize and sympathize with the fact that faith can inspire people to do wonderful and heroic things.

This is important when we see nascent political movements come and go. Many claim to be of no particular faith, some of no faith at all, still others purporting to be of and for all faiths. This is well and good, and my work. But concerted action of a type that actually gets good stuff done, and doesn’t just subvert, tends to be successfully accomplished by groups that are homogenous in some way. Often this is ethnicity or nationality. Often it is religious. In the case of Greeks, where some 99 percent are Orthodox Christians, it is both.

Religion actually has proven to be a powerful tie that binds. One can say that nationality or ethnicity can trump this, as in the case of mostly atheist and secular European nations and, for all intents and purposes, the United States as well. But facts bear out the opposite. The U.S. and most of Europe has proven fundamentally incapable of defending themselves from much of anything, allowing what are invaders by any other name to waltz right in . . . and then they treat the invaders like conquerors instead of defending the interests of their actual people.

Is this due specifically to the weakening of religious identity? I argue that this is so. Interestingly, one of the few European nations that has actually used force to repel the non-stop invasion into their land has been little Greece. Yes, the Greek military successfully performed a task that has baffled and mystified the mighty United States Armed Forces for sixty years: it actually defended its border.

For another example of this, look at the Muslim world. It’s not called “the Arab” world, partially because not all members of it are Arab–there are Persians and Africans and Turks and Azeris and Asians and Azeris and Chechens, to name but a few. But more so because is defined by its religion. Whether you like their religion or not is irrelevant: Islam has helped these nations maintain their own distinct cultures and norms against intrusion from the West and elsewhere. We seem to think it’s so weird that these countries don’t want Pepsi and McDonalds and pop music and blue jeans and freedom and democracy and stuff, but that’s their prerogative. They’ve resisted this sometimes with violence (and who can blame a nation for reacting violently to foreign armies on its soil?), but very much so also without. Would that the West could learn this lesson, or remember it the way the Greeks did two hundred years ago today.

It’s not about God being “on your side.” It’s about making sure that you are on God’s. We aren’t voting our way out of this mess, and we aren’t going to be held together by mere economic considerations (“The economy is good! Why are you so unhappy?”).

Poorer, less materially abundant societies have been, and are, happier and more fulfilled than ours. The answer isn’t “more stuff, more ease, and more convenience.”

And the other great American shibboleth–“freedom”–is often espoused without asking the all-important follow-up question, “freedom to what?”

Like it or not, religion gives a people a reason to move forward, to live and build and have families in the face of conditions that were far, far worse than those we live in today.

Don’t be a disgrace to those who came before you, and don’t do an unforgivable disservice to those who will come after.

There is more to life than money and comfort and ease–much more. A civilization that forgets this won’t last much longer. Indoor plumbing, modern sanitation, and medicine are miracles of human innovation. The rest, quite literally, is gravy.

And anyway, my ancestors didn’t fight and die and procreate and hope and pray so I and other Greeks could live a sterile, Godless, degenerate existence in a foreign land that was good enough to take us in.

Neither did yours, whomever you are.

I am aware that modern Greece is more culturally Orthodox than spiritually. Still, it remains a rallying point that binds Greeks around the world together.

Further reading: Brian Neimeier, “Get off the bench.”

These characters, man and alien alike, respect their roots.

March 24, 2021

It’s Hard to Recognize

It’s a sad state of affairs when somebody decent who performs good works and asks nothing in return–and may even be openly religious–is viewed as suspect, while we are more comfortable with frauds, hucksters, and liars. “Well, I’d rather be able to identify the fraud, huckster, and liar!” might be one defense, but that doesn’t make much sense to me, as any fraud, huckster, or liar would be inclined to hide their true intentions.

But further, the psychological and spiritual damage done to a society for this to be the case in the first place must have been pretty grand indeed.

Imagine the psychological and spiritual damage done to a society that anyone who comes across as a decent person not asking for anything in return is viewed with intense suspicion, but it understands and is more comfortable with, liars, hucksters, and frauds.

— Alexander Hellene

(@AHelleneAuthor) March 22, 2021

From whence does this stem? Let’s take a look at what’s left of our culture, and in that case it sadly usually means movies and TV shows, though this trope appears in books as well. Whenever you see somebody who seems too good to be true, i.e., a good human being doing the right thing for no reward, you know that 99 percent of the time, they’re the real bad guy. The person whose motives are pure at the outset will be the bad guy, while the rough, morally ambiguous anti-hero type will be the one doing the right thing. Why? For reasons: “I might be an amoral killer, but at least I’m not a Nazi,” that sort of thing.

I get it, because this trope works, or maybe it did for the first few years it was trotted out. But it’s nearly ubiquitous and it makes our entertainment so predictable–especially if the good person in question openly professes their Christianity–as to become a joke. And yet it remains.

Does this trope reflect reality, or does it drive reality? Has mass culture in the form of storytelling so poisoned our culture, made it so cynical, that nobody can take anybody good at face value?

Perhaps. And look, I’m generally on board with viewing everything that happens in America as fake, because it is . . . at least on the official story on the national stage. But in our personal lives, and even in our stories, a change of frame is required.

But love ye your enemies, and do good, and lend, hoping for nothing again; and your reward shall be great, and ye shall be the children of the Highest: for he is kind unto the unthankful and to the evil.

— Luke 6:35

Regardless of your religious predilection, this is good advice for you and your children. You will not change society unless you change yourself and your family, and yes, the culture.

But culture has many meanings. It can be culture as in art, the stories we tell and the songs we sing, and it can also be the culture of your household and community.

Be wise as serpents and as simple as doves. The official story is a fabrication 99 times out of 100 . . . but your neighbor is probably a good guy.

March 22, 2021

Book Review: The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn: Part Two: “Perpetual Motion,” Chapter Four, “From Island to Island”

And so we’re here, at the end of Part Two of Russian intellectual Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s most known work. Befitting his status as a total legend, Solzhenitsyn has taken us through, in these first two parts, a historical and sometimes circuitous route to answering the burning question most people have upon cracking open his story: What’s it like in the camps?

We’ve talked about the Soviet secret police’s arrest tactics and interrogation methods. We’ve learned about what it’s like in jail. We’ve been given a rather extensive survey of the history of the Soviet legal system, including the infamous Article 58. We’ve been given an overview of many, many landmark Soviet legal cases. We’ve delved into the psychology of prisoners waiting to be transported to the Gulag. And that was just in Part One.

In Part Two, Solzhenitsyn has taken us maddeningly, excruciatingly, through all the ways that prisoners were transported and stored on the way to the camps, explaining the usage of his term “Gulag Archipelago” with the metaphor of ships (modes of transportation) and ports (temporary transit prisons) Perhaps he went into too much detail. Perhaps he does not go into enough. But if merely getting there is this torturous, this laborious, this coldly and blandly sadistic, then what’s it like in the camps?

Here, at the end of Part Two of Five, and the last part in this particular volume based upon how the publisher decided to divide it up, we . . . still don’t really get a peek into life in the camps. No, Solzhenitsyn instead illuminates for us one final mode of prisoner transportation, one that he himself experienced:

And zeks [prisoners] are also moved from island to island of the Archipelago simply in solitary skiffs. This is called special convoy. It is the most unconstrained mode of transport. It can hardly be distinguished from free travel. Only a few prisoners are delivered in this way. I, in my own career as a prisoner, made three such journeys.

The special convoy is assigned on orders from high officials.

To prisoners used to the abuse and inhumane treatment of the Stolypin cars or Black Marias or red cattle cars, the special convoy is a godsend, though a cruel one. Traveling with one, maybe two or three guards, the prisoner is not bound, not beaten, not even verbally abused, though he knows if he makes a break for it he will be shot on sight. Instead, the prisoner may actually travel by normal train like a normal person and told to act as naturally as possible. This is harder than it sounds, for the prisoner knows that the ruse is up once they reach their final destination. Such is the strange vagary of totalitarianism: the appearance of normalcy must be presented even though everyone knows there is no recourse for the most barbaric cruelties inflicted upon its subjects.

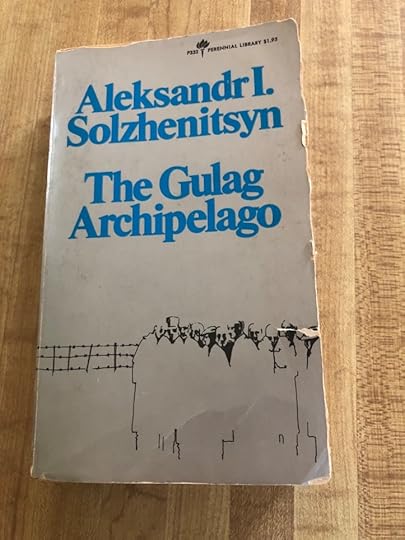

Solzhenitsyn’s life changed when, in camp (though he doesn’t give any more details about the camp) he was told he was to be transported by direct order of Minister of Internal Affairs Sergei Kruglov himself.

But why?

Soviet Minister of Internal Affairs Sergei Nikiforovich Kruglov (1946-1956)

Soviet Minister of Internal Affairs Sergei Nikiforovich Kruglov (1946-1956)Solzhenitsyn posits his theory. When given his customary Gulag registration card, upon which, among other vital information, the zeks were to write their occupation, Solzhenitsyn “frowned and filled in ‘nuclear physicist.'”

He was not, nor had he ever been, a nuclear physicist.

As an aside: why are we, those of us alive and still relatively free in the twenty-first century, so interested in what it’s like in prison and labor camps? Is it because all we hear about in 20th century history classes and books and documentaries is the horror of prison camps? Is it because many of us expect to be in one someday soon?

This point is this, though: The Gulag is more than just the camps.

Solzhenitsyn says he soon forgot about the card, until he was pulled aside on Kruglov’s direct order some time later. Prisoners knew that there were only a few possible meanings of this: a new stretch of prison . . . or being released. But one thing they all knew is that once Kruglov had his eye on you, there was no escape.

He then recounts a mysterious, unconfirmed rumor among prisoners at the camps:

There was a vague, unverified legend, unconfirmed by anybody, that you might nevertheless hear in camp: that somewhere in this Archipelago were tiny paradise islands. No one had seen them. No one had been there. Whoever had, kept silent about them and never let on. On those islands, they said, flowed rivers of milk and honey, and eggs and sour cream were the least of what they fed you; things were neat and clean, they said, and it was always warm, and the only work was mental work–and all of it super-supersecret.

And so it was that i got to those paradise islands myself (in convict lingo they are called “sharashkas”) and spent half my sentence on them. It’s to them i owe my survival, for I would never have lived out my whole term in the camps. And it’s to them i owe the fact that I am writing this investigation, even though I have not allowed them any place in this book. (I have already written a novel about them.) And it was from one to another of those islands, from the first to the second, and from the second to the third, that I was transported on a special-convoy basis: two jailers and I.

The experience was surreal. Solzhenitsyn likens it to being a would of the dead hovering above the living and just observing but not participating. “Act naturally . . .” How could anyone act naturally in such a circumstance? Solzhenitsyn shares a humorous anecdote of sitting in a separate car from his guards, though they kept their eye on him, and speaking with another traveler who joined him–Solzhenitsyn even drinks a proffered beer (he was told to “act naturally,” after all) . . . only to deduce later that his companion, too, was a member of the secret police. The Gulag was truly a small world after all.

“After spending a few hours among free people,” Solzhenitsyn notes, “here is what I feel: My lips are mute; there is no place for me among them; my hands are tied here. I want free speech! I want to go back to my native land! I want to go home to the Archipelago!” Such is the psychological toll being tormented by the state has wrought.

And where did Solzhenitsyn end up first? Why, back in Butyrki Prison in Moscow!

Butyrki Prison, Moscow

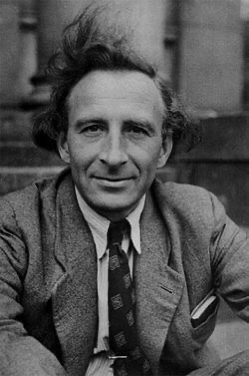

Butyrki Prison, MoscowIt was like coming home. Not only were the conditions far, far better than those in the ships and the ports of the Archipelago, not only was there more food, more warmth, and books, and sleep–oh, precious sleep. Importantly, Solzhenitsyn found some wonderful company among the prisoners–though he had to fudge his knowledge of nuclear physics, he befriended many intelligent people who sparked wonderful discussions about science and philosophy, including the famous biologist Nikolai Timofeyev-Ressovsky, the President of the Scientific and Technical Society of Cell 75. Professor Timofeyev-Ressovsky had the misfortune of studying and conducting research in Germany before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Nikolai Timofeyev-Ressovsky

Nikolai Timofeyev-RessovskyAlong with his colleague Sergei Tsarapkin, Timofeyev-Ressovsky naively thought that Soviet soldiers would let him continue his research in Russia. However, when the soldiers set about ransacking his laboratory, Timofeyev-Ressovsky objected, which naturally made him an enemy. So into the Butyrki he went!

Solzhenitsyn reports these as happy times, proving that there is a silver lining everywhere:

No, even before the war, when I was studying at two higher educational institutions at the same time and earning my way by tutoring, and striving to write too, even then I had not experienced such full, such heart-rending, such completely filled days, as I did in Cell 75 that summer.

It wasn’t all easy, though. Displaying the black humor that has gotten Russians through many a hardship, Solzhenitsyn explains a little in-joke among the zeks:

And on the bowls will be stamped (so we shouldn’t make off with them in the prisoner transport) the mark “Bu-Tyur”–for Butyskraya Tyurma, Butyrki Prison. The “BuTyur ” Health Resort, as we mocked it last time. A health resort, incidentally, very little known to the paunchy bigwigs who want so badly to lose weight. They drag their stomachs to Kislovodsk, and go out for long hikes on prescribed trails, do push-ups, and sweat for a whole month just to lose four to six pounds. And there in the “BuTyur” Health Resort, right near them, anyone of them could lose seventeen or eighteen pounds just like that, in one week, without doing any exercises at all.

This is a tried and true method. It has never failed.

Solzhenitsyn was later moved into the second story of a church that was converted into a prison–the Soviet state never let anything go to waste, after all–waiting to be moved to where Comrade Kruglov would send him. He encounters a Romanian spy and several other interesting folks, but most of all he is struck by the attitude of those prisoners of the younger generation. For starters, they were not immediately dismissive of religion, and more than a few were believers themselves. What these younger prisoners weren’t was believes in the Soviet system. Solzhenitsyn notices that their alienation and lack of hope actually gave them fatalistic clarity. They don’t need to fight for the Motherland and try to build a good life, have it stripped from them, and then see the rot and evil inherent in the system.

These young people thrown into the Gulag meat-grinder never had anything to begin with. They see the system the way it is from the get-go, and realize that what had been taken from them is what they need to return to some semblance of goodness and decency. The parallels between American Millennials–analogies to Solzhenitsyn’s generation–and Zoomers–these young ones Solzhenitsyn encountered in the church cell–is chilling:

Our generation would return [from the war]–having turned in its weapons, jingling its heroes’ medals, proudly telling its combat stories. And our younger brothers would only look at us contemptuously: Oh, you stupid dolts!

***

Though it comes early in the chapter, I find these words of wisdom a good way to close out our survey of The Gulag Archipelago, Vol. 1 (Parts One and Two). It’s taken me a long time to read, digest, analyze, and write-up each chapter of this landmark work, but I’ve found it very educational and thought-provoking. I hope you’ve gotten some sort of value out of it too, and we’ll see you in Volume 2!

Do not pursue what is illusory–property and position: all that is gained at the expense of your nerves decade after decade, and is confiscated in one fell night. Live with a steady superiority over life–don’t be afraid of misfortune, and do not yearn after happiness; it is, after all, the same: the bitter doesn’t last forever, and the sweet never fills the cup to overflowing. It is enough if you don’t freeze in the cold and if thirst and hunger don’t claw at your insides. If your back isn’t broken, if your feet can walk, if both arms can bend, if both eyes see, and if both ears hear, then whom would you envy? And why? Our envy of others devours us most of all. Rub your eyes and purify your heart–and prize above all else in the world those who love you and who wish you well. Do not hurt them or scold them, and never part from any of them in anger; after all, you simply do not know: it might be your last act before your arrest, and that will be how you are imprinted in their memory!

Takeaways:

There is no logic or reason in a dictatorship. There is friend/enemy. That’s it. That’s all that matters. Learn this or go mad.Freedom takes practice, and human beings learn to fit their container. If you’re in jail long enough, that becomes your frame of reference, your normal, after time. Opporessors know this and use this.Oppressive, soulless states will use people like widgets, like tools. This can inure to one’s personal benefit, but it’s illusory.Generations view things differently because they have different life experiences. All generations need to work together and understand one another, and the older must look after the younger or else.March 19, 2021

And Why Not?

There’s a pervasive theme in the zeitgeist that things are not right. One might feel it like an unsettling churning in the pit of one’s stomach, or a frantic thrashing of one’s soul. Whatever it is, the underlying thought is, This is wrong, and I don’t know what to do about it.

It’s no wonder, then, that in this milieu once forbidden ideas are being looked at and not with her but with interest and curiosity. “Would X really be so bad?” is heard in many circles, regardless of where they fall on the political spectrum. “Wouldn’t Y be so, so much better than this?”

Complicating matters are the restrictive dichotomies we find in American discourse. You’re either Republican or Democrat, communist or capitalist, a fan of Socialism or democracy. There are no other choices. It’s one or the other. Lesser of two evils. “Well we might not have the best system, but it’s better than all the others.”

Is it? I find it hard to hold such convictions, and can’t understand how anyone else does, given the lack of imagination when it comes to other possibilities. The only choices aren’t Marx or whatever you want to call what we have now. Further, many, many criticisms of capitalism are perfectly valid but get immediately dismissed by those on the right side of the spectrum because “That’s what a socialist would say!”

I was raised as a traditional conservative, some might say Republican, and while I am still sympathetic to many of those tenets, I find several of them lacking. among those, the unwavering belief in a free unregulated market, so-called free trade, and a laissez-faire attitude towards big businesses and corporations. There are others: for example, I’m not against regulation or taxation. I’m not even against corporate taxation. In fact, I think corporations might need to be regulated in taxed more to bring them to heel.

My biggest beef, though, is how so many normal main stream middle of the road conservative type of GOP people categorically refusing to see that corporations have become as powerful or more powerful than the actual government, and in fact may control the government, and that they refuse to see this as a bad thing, or refuse to use governmental power when they have it because of misplaced ideals about the purity of small government.

What do we do about this? I don’t know. I’m not a policy guy. I have ideas, but putting them into practice? I couldn’t tell you how they would pan out. But what I can tell you is that categorically refused to even entertain alternatives is pushing people to what were once considered extreme fringe ideas is totally beyond the pale but are now being discussed as viable, even desirable alternative.

And it’s hard not to feel this way, when literally the only explanation for the complete and utter insanity we’ve seen in the past two decades or more can only be actual malice. This is not mere stupidity. Our enemies are not just wrong. They are evil.

But I don’t know if I am more angry at those in power, or the regular people who think that everything is fine.

Here’s the kicker though: the way things are going actually benefit quite a few people and their families. I put it to the tune of about a third of the country. Ever wonder why Joseph Stalin is actually remembered quite fondly by many Russians? Because life under him, and under the USSR in general, was actually preferable to what came before for a wide swath of people. We have course hear about the dissidents and those who oppose communism, atheism, and the Soviet state. But lots of people loved it. Their lives improved. How do you circle that square?

Do you think that the people who stand to benefit, and are currently benefiting, from the new America that we find ourselves morphing into are going to be persuaded that they’re wrong by something as Quotidien as history? You’re dreaming.

Whatever you want to call the current era were living in, I like the Age of Fakery myself, it is undeniable that it is the direct result of ideals that we want held as sacrosanct.

If we can’t even talk about this stuff, we can’t act surprised when once abhorrent ideas are greeted with a shrug and a weary utterance of, “And why not?”

Sword-and-planet fiction that says “And why not?” to the fantastical and fun.

March 17, 2021

You Are What You Read

I haven’t been reading much sci-fi or fantasy lately. The last few books I’ve finished have included American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis, Fight Club by Chuck Palahniuk, and The Gulag Archipelago (parts I and II) by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (review of the final chapter coming soon), Not All Fairy Tales of Happy Endings: The Rise and Fall of Sierra On-Line As Told by the Ultimate Insider by Ken Williams. Currently, I’m reading Spring Snow by Yukio Mishima, and am going to start American Pilgrim by Roosh Valizadeh (his story of giving up his hedonistic lifestyle and returning to Orthodox Christianity). In fact, other than Neon Harvest by Jon Mollison, I haven’t read a sci-fi or fantasy book in 2021–the last was The Rise of Endymion by Dan Simmons, which I finished last fall and reviewed on October 21 of 2020.

There are so many great pulp authors on my to read list–including A.E. van Vogt, H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton, Leigh Brackett, A. Merritt, and Poul Anderson, as well as more by Robert E. Howard, Jack Vance, and Edgar Rice Burroughs–as well as some newer books by Tad Williams (fantasy) and swashbuckling adventure (Arturo Pérez-Reverte) that I don’t even know where to start. And I’m looking forward to these books! It’s just that I’ve found myself getting supercharged to write my own pulp-inspired sci-fi by reading books that are decidedly not pulp or pulp-inspired sci-fi or fantasy.

This used to happen when I was writing and playing a lot of music. The stuff I right tends to be traditional rock-inspired, melodic, and loud-and-fast. I like catchy melodies, loud power chords, and just a little bit of insanity thrown in. Yet I’d find myself listening to a lot of avant-garde stuff and prog-rock, as well as ultra heavy hardcore and death-metal, and not exclusivley new wave and punk while I was in a female-fronted pop-punk band. Kind of incongruous, but I found that grafting tropes and idioms from supposedly foreign genres helped me keep things fresh and inspired.

Writing is a similar case. Imbibing classic works in my milieu of choice helps get the creative juices flowing, and provides a familiarity with a genre and its tropes. I read almost exclusively fantasy and the classics when I was younger until I was about twenty-five or so, and then really branched out into the dreaded realm of literary fiction (which I like) while still keeping one foot in the fantasy fiction camp.

But lately, I don’t know. Maybe I’ve just seen too many of those tropes before I don’t find them inspiring to read about. I’ll read the back cover or Amazon description of highly regarded and recommended fantasy fiction, and it just sounds like stuff I’ve read so many times before. Ditto with sci-fi, which is why Dan Simmons’s Hyperion Cantos was so mind-blowing–it was so different. He took the familiar but really made it feel fresh, not by subverting, but by finding cracks and spaces in genre conventions where others had not explored. It had the wonder, scope, splendor, philosophy, and intellect–as well as the flat-out good writing–of Frank Herbert’s first Dune book, just for multiple books instead of just one, maybe one-and-a-half.

Here’s the thing: I could tell that Dan Simmons read stuff other than sci-fi. A lot of other stuff.

Contrast this with John Scalzi, whose one book I read just screamed to me that all he read was sci-fi, and what other people in fanzines and on the Internet said about sci-fi. I could be wrong–in fact, I probably am–but this is what Old Man’s War felt like.

This is where I am at now as I work through the as-yet untitled third Swordbringer book. I’ll read these non-fiction or non-sci-fi or fantasy works, and get pumped to write. I don’t want to write the next Fight Club (okay, I mean I DO; don’t we all? But you know what I mean), but I want to use what I absorb from authors like Palahniuk in my own work to hopefully create something new and fresh.

I also get inspired by old video games and rock lyrics, though, so take all of this with however many grains of salt you want.

The Swordbringer, Books 1 and 2, available here!