S. Jacques Stratton's Blog

August 5, 2025

Notes from the Bookfair

Mixing overtones of swap meet and art fest, the L.A. TimesFestival of Books presents an enigmatic facade. Where the cynic sees a marketing circus, the optimist finds acelebration of literary inspiration. People capable of a more subtle perspective may perceive the bookfair asa gathering of dualities: the soulful andthe corporate, the silly and the serious, the creative and the commercial.

Held in late April on the stately grounds of USC, thebookfair draws roughly 150,000 attendees, who circulate among the canopies of severalhundred vendors. (Anyone unfortunateenough to drive near USC during this time will likely add bookfair traffic tothe long list of complaints about living in L.A.) For the vendor, the crowd represents anopportunity to get a product before more eyeballs in less time than mostpublishing schemes. The vending booth functions like a highway billboard, enticing the impulse buyer to make apurchase and instilling in others a subliminal imprint for futuresales. However, in the manner ofdualities, the very size of the bookfair creates its chief flaw. Lost in a maze of vending booths, the dazedattendees walk like zombies, their brains overwhelmed by the barrage ofposters, flyers, and other promotional ammunition assaulting them from everydirection. Amid such chaos, people trulydo judge a book by its cover--if they manage to see it at all.

As an obscure author working with a niche publisher, I oftenwonder where to draw the line between sensible marketing and vanityextravagance. Deciphering the murky correlationbetween promotion and sales requires a business acumen beyond my artisticsensibilities. Fortunately, I write forfun--in other words, to indulge my vagabond mental digressions--and know enoughabout America’s reading preferences to realize the surf travel memoir, the“genre” in which I specialize, won’t resonate with a mainstream audience eagerfor romance or mystery novels. Whateconomists call the Law of Diminishing Returns applies with callous efficiencyin niche markets. Additionally,statistics show that most book sales take place via Amazon. Despite trade organization reports showingthat print books dominate total sales revenue, I suspect digital format sales(e-book and subscription KENP) outnumber print in terms of unit volume. For my travel memoir, print copies accountfor only 30% of units sold, a statistic easily explained by price differentials: the e-book costs roughly one-tenth theprice of the paperback, while the KENP offers the convenient perks ofkindle. In light of this trend, bookfairs seem like anachronistic and possibly counter-productive forms ofmarketing. A Google search aboutauthors’ bookfair experiences yields many curmudgeons who contend the eventsexist primarily to enrich the organizers.

But I regard the writer’s journey as a marathon, not asprint, and sometimes that means viewing opportunities in terms of passionrather than finance. One never knows whatsynergies might result from placing a product of creative energy before thepublic eye. Like a splash in a cosmicpond, the melding of book and reader might create ripples that transcendbalance sheet metrics.

Emboldened by such idealism--what experienced booksellers mightcall wishful thinking--I followed my entrepreneurial muse to USC, undeterred bya late season rainstorm that brought echoes of winter to normally sunny L.A.,taco trucks that ransomed nachos for twenty dollars a plate, and embarrassingdisplays of shameless self-promotion (“buy my book! You’ll love my book!” holleredone exuberant vendor). Promoting mywares, I rediscovered customer service skills dormant since college, pondereddeep questions about the aesthetics of display, and joined my fellow vendors ina rite of passage: lugging boxes ofunsold inventory back to the parking garage. As a stepping-stone on mywriter’s journey, the experience provided some important tidbits ofwisdom:

--have fun!

Often, the world will express indifference to the artisticcreation for which you’ve staked so much time and effort. Watching the portion of humanity whosupposedly loves reading (a not unreasonable supposition about bookfairattendees) give you the cold shoulder emphasizes this indifference in a uniquelycallous way. For the aspiring author,humor lessens the tendency to interpret public apathy as a personal indictmentand grants a more playful perspective. As if to emphasize this point, USC kicksoff the bookfair by trotting out several dozen of their finest cheerleaders toget everyone properly excited. Scantilyclad, swinging their legs like aspiring Rockettes, these nymphs provide a spicyreminder of how attitude influences experience. If you doubt the value of this promotional stunt, consider that in L.A.,a city devoted to botox beauty and credit card lifestyles, artifice oftenspeaks louder than art. To generalizefrom a Cheryl Crow song, all the people want to do is have some fun, and whenthe sun comes up over Exposition Park, they remember those who put the “fest”in festival. For authors, this mightmean including some carnival games with books as prizes, or wearing edgyclothing, such as a shirt that says “writers do it with imagination” (you’d besurprised at the sort of people intrigued by this slogan).

-- Cultivate authentic connections. . .

Today’s screen-mediated culture makes human connectionsincreasingly elusive. Yet we remainsocial creatures who crave conversation and proof that we know how to functionwithout the internet. As a catalyst forcuriosity, a book can attract people who might otherwise remain aloof. I’ll long remember the conversation I hadwith Alexx, a college student drawn to the cover design of my travel memoir. Questions about the book led to talk of surftravel, and I soon discovered that this girl half my age boasted a travelresume that put me to shame. We had somuch fun discussing bucket list destinations that we ignored the unpleasantryof a passing rainsquall. Similarlymemorable was my conversation with Paul, a true So Cal waterman whose photos ofmarine life encountered during his open ocean swims merited a coffee tableedition. These and other encounters occurredbecause my travel memoir provided a bridge to moments of shared experience.

Of course, some who browse your wares care little aboutconnection. The bookfair abounds with folks who come notfor the books but for the giveaways: pens, notepads, coasters, and assorted useless-but-free baubles which makepetty materialists salivate. Include theinsistent trickle of interlopers looking to pitch their gimmicks--bookmarketing schemes, audiobook narrations, etc.--and you soon suspect evengenuine customers of ulterior motives. My advice? Borrow a page from theinterloper’s playbook and consider how you might implement your own proactive schmoozingagenda. Walk among the booths, expressinterest in some books that intrigue you, and offer the author a copy of yourbook in exchange. (This works best forbooks in similar genres.) Not only willyou lighten your inventory, but you’ll likely enjoy some worthwhileconversation and possibly connect on LinkedIn.

--Keep things in perspective. . .

It’s tempting to think that inclusion in one of the world’slargest bookfair events will garner your title a commensurate promotionalbuzz. Lest delusions of grandeur pavethe way for disappointment, do some sober research on the sales metrics typicalof swap-meet retailing. To start,consider the cold-caller’s “one percent rule:” for every hundred peoplesolicited, ten might express interest, and of those, one might make apurchase. Then, reduce this further toaccount for the fact that 1) only a small portion of bookfair attendees willactually approach your booth, 2) only a fraction of these “prospects” willappreciate your genre specialty, and 3) only a fraction of those will give yourbook open-minded consideration rather than cynical prejudice. In other words, for obscure authors, thedistribution of probable outcomes skews toward a low-sales number. But a silver lining shimmers for thosewilling to perceive it. First, a lowsales volume says more about the whimsical nature of shoppers than the literaryquality of a book. Second, the disappointment of selling ten copies where you hoped tosell fifty subsides when you realize that on Amazon, selling ten copies in oneday would likely propel that title temporarily into the top ranks of thegenre. Finally, if you perceive thebookfair not as a showcase for books but rather an educational experience forauthors, you might find you learned valuable lessons.

Is the bookfair worthit? Such a question invokes the wrongassessment criteria, reducing the event to mere balance sheet metrics. I sold fewer books than hoped, but enough toaffirm my efforts. Accordingly, I mightpose a different question: does thebookfair take you further along the author’s journey? Literary circles give the “authorprocess” relatively little fanfare, disdaining humdrum topics like marketingand brand development, but it actually has much in common with the writing process. Building a readership requires dedication,sacrifice, and doubt-inducing setbacks. Likethe writing process, it’s a marathon, not a sprint. You make progress in increments ofperseverance. Then, riding your secondwind, you find beautiful moments otherwise unperceived.

Speaking of beautiful moments, did I mention those USCcheerleaders?

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073697537 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

March 12, 2024

Writing Like We Talk: The Stylistic Implications

The popularreception of Mark Twain’s writings prompted critics to view the depiction ofcolloquial speech in literary texts as legitimate art, enhancing realist,modernist, and contemporary fiction. Yetsuch depictions require caution, for non-literary forms, when mingled withliterary discourse, pose significant stylistic concerns.

Oral discourse,and the modes often associated with it--movies, television, and modern theater, forexample--convey immediacy and emotion, characterized by pause fillers, emphaticintonations, and street slang. Literary texts,on the other hand, connote cautious, planned, respectable language, the hallmarkof intellectual society. The polarityextends further: composed of the best inlanguage and thought, literature enjoys elite patrons and political prestige, suchthat many scholars to consider it a yardstick of culture. However, decades of technological andcultural change have eroded the distinction between literary and non-literarydiscourse. In the era of texting andemojis, steadfast adherence to literary convention risks archaic formality.

Knowing the formsorality takes in writing can help writers make more conscious sentence-levelchoices. Quotes, perhaps the mostobvious conversational marker, represent a decision to distance quoted materialfrom the surrounding authorial voice. Responsibilityfor the material, the quotes imply, belongs elsewhere. Quotation marks, then, serve an importantrhetorical function. Employing themsignifies a choice to call on outside voices, mingling a text’s literaryquality with conversational elements that, depending on context, may indicatethe writer’s deference to authority (and, by extension, intellectual privateproperty) or create distance between the author and statements deemed unfit fordirect association.

To the extent that quotation marks signify extra-textual language, we may regard them as conversational. However, not until thepost-Twain era did writers develop informal conversation as a literarytrope. To glimpse the formality withwhich prior authors treated conversation, we might highlight the 18thCentury literary figure Samuel Johnson, whose biographer recorded conversationsnot in an immediate, emotional manner, but rather in planned aestheticsentences. Presenting conversationaccording to the literary standards of the day, the biographer (Boswell) eschewed theconversational markers (italics, pause fillers, fragments, etc.) that pervademodern texts. By contrast, modernwriters embrace features considered too informal by 18th Centurystandards. Italics, for example, disruptthe visual uniformity of text in a way that suggests drama and emphasis. Pay attention to this, they convey! Since writing offers other means of emphasis, such as placing new information at the end of a clause, italics constitute adecision to favor the immediacy of oral markers. Beyond italics, writers might employadditional techniques. Running wordstogether (“whodunnit” for example) brings the hurried pace of oral discourse toa text by calling our attention not to the word but to the phonetic qualitiesof rapid speech. Insofar as phonetics denote sound, foregrounding them implies a choice to create urgencyvia nonliterary means. Similarly, theemotional tone suggested by fragments (i.e. “yummy!”) and the mental stumblessuggested by pause fillers (“um,” “well”), when written, bring emotionalimmediacy, imbuing the text with an improvised, even frenetic, tone.

The markersdiscussed above present a key stylistic concern for writers. Emphasizing a conversational tone through oraltext markers often means denying the use of literate methods. When a writer foregrounds orality to excess,so that, as with strung-together words, the text unintentionally reads like acomic book, readers may conclude the writer lacks control. Accordingly, recognizing the features ofboth literary and oral discourse can help writers more fully appreciate howmode affects meaning. Once chosen, amode involves expectations and requirements. Just as graffiti requires an illicit canvas, and loses itscounter-culture impact if transmitted via Morse code or communicated through aTV commercial, so must writing intended as literature adhere to the expectationsof the literary mode. Here theaesthetics of the pre-Twain eras retain their value: while conversational markerscan enhance a writer’s literary toolkit, they can’t in themselves substitutefor literature.

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073697537 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

January 15, 2024

Rhetoric in the Writing Classroom: Tracing an Ancient Heritage

Mocked as uptightgrammarians, more often typecast as junior-high schoolmarms than poeticpersonalities, English teachers, contrary to stereotype, actually continue a nobletradition whose origins date back to the Greco-Roman beginnings of Westerncivilization. A scholarly anthologytitled Essays on Classical Rhetoric and Modern Discourse explores thisancient heritage, linking today’s writing classroom with the great names inrhetoric from Greek and Roman times. Notingthe influence of such luminaries as Plato, Aristotle, and Quintilian, the book tracesthe evolution of rhetoric through time, providing a fascinating perspective onhow rhetoric and the quest for truth relate historically and inform Englishcourses today.

While “quest fortruth” perhaps overly-dramatizes what writing students experience, Plato teachesthat a spiritual element underlies writing pursued as an act of discovery. An essay by Jeremy Golden elaborates: “thesubject of knowledge. . .has as its starting and finishing points ideal formssituated in the mind of God. The forms.. .represent the ultimate truth to be sought.” Plato’s rhetorical forms--particularly the famous dialectic--function asyoga for the mind, deepening the awareness of dedicated rhetoricians. The dialectic, defined as “purifying” processof refutation and re-examination, provides a strategic formula for clarifyingideas, developing arguments, and thinking critically. Today, English teachers invoke a basicdialectic when they encourage students to write with a reader’sperspective. Switching roles fromwriter-based text generation to reader-based text evaluation helps students clarifyunstated assumptions and encourages a revision of content and phrasing thatteachers might call “sentence truth.”

Plato looms largenot only for his direct influence on rhetoric but as a counterpoint for otherthinkers who modified his ideas through time. An essay by James Kinneavy describes these changes and theirperpetrators: “on the issue of epistemology Isocrates directly opposed Plato. ..In speech after speech he inveighed against the type of theory and sciencerepresented by Parmenides and Plato.” Similarto the Sophists, a group skilled at using emotional appeals and figures ofspeech to persuade audiences, Isocrates knew how style could influence jurors, andbegan a school dedicated to the intense practice of courtroom oratory. Unlike Plato, he did not attribute a spiritualvalue to the theory of forms nor did he require true evidence to support hisarguments. Rather, the school emphasizedimitation and manner, an approach which ultimately had a lasting effect onrhetoric and Isocrates’ place in history. Says Kinneavy: “It was through these kinds of discourse, learned by analmost mechanical imitation, that most of the writers of western civilizationin antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance learned to write. Isocrates, in this sense, is the father ofwestern humanism.” Though criticizedthrough history for their emphasis on style over substance, the Sophistsnevertheless exert an influence in the today’s writing classroom. When English teachers call attention to modeltexts, literary tropes, and artistic devices (e.g., parallel structure, activevoice phrasings, etc.), they echo Sophist principles that emphasize stylisticpresentation.

Other names deservehonorable mention. The widely taught(and widely disliked) five-paragraph essay originated with Quintilian, a Romanwho thought it the ideal form for courtroom oratory. An introductory paragraph sought to win thesympathies of the jurors; a magic number of three supporting arguments soughtto justify those sympathies; and finally the conclusion reminded the jury whythey felt sympathetic. Though criticizedby many teachers as artificial and impractical, a form stifling to creativityand irrelevant to how actual writers approach real-world writing tasks, thefive-paragraph model nevertheless exemplifies the enduring influence ofclassical rhetoric. At its core, writingconsists of assertion and proof, a conceptual movement from general to specific(and vice-versa), patterns the five-paragraph model emphaticallyreinforces. Designed for courtroomoratory, the five-paragraph model emphasizes that writers function inpartnership with an audience who expects clarity and organization. The fact that English textbooks have devotedmore ink to the five-paragraph format that any other organizational approach testifiesto Quintilian’s legacy.

The editors ofthe book conclude with a message for English departments in particular andacademic institutions in general. At onetime, no departments existed in colleges, and rhetoric represented the maindiscipline. During the NineteenthCentury, however, the Belles-lettres movement downplayed ancient rhetoricinfluences, advocating English studies in place of the classics. The discipline of English severed fromrhetoric (later the concern of Speech Communication) to the detriment ofboth. While many attempts to re-unifythe two disciplines took place over the years, not until the publication of Rhetoric: Principles and Usage by Duhaumel andHughes did classical rhetoric return as a subject worthy of Englishstudies. The challenge of rhetorictoday, contend the editors of Essays on Classical Rhetoric and ModernDiscourse, is to unite disciplines previously in contention with one another,to the advantage of both.

In light ofrecent instructional trends, the book perhaps offers an additionalmessage: proper writing instructionemphasizes the principles of classical rhetoric. At a time when English teachers increasinglyembrace identity politics, masquerading as sociologists while they discuss“positionality,” “asymmetrical power structures,” and other notions borrowedfrom post-deconstructionist, post-relevant discourse theory, the practicalpurpose of English courses increasingly diminishes. Most students today express little interest inagitation propaganda. Juggling work, school, and family obligations, they seeknot to disrupt the dominant paradigm but find a place within it. In this regard they have much in common withthe tunic-clad Athenian youth who, admiring Plato in 400 B.C., sought insightfrom “the good person speaking well.”

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-469750017 -1040178053 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

September 19, 2023

Postmodern Nonsense Poetry: Liberation or Lunacy?

Language poetry,often considered an offshoot of postmodern literature, occupies an obscureniche of the literary world. The genre’stwisted syntax, mixing of registers, and grammatical ambiguities confusereaders, leading the unappreciative to complain that language poets write for anaudience of linguists. Defenders of thegenre dismiss such criticism as ignorance of the poets’ true intent. Language poetry proceeds from the assumptionthat “sensible” language patterns and literary techniques oppress the readerbecause sensible language reproduces the ideology of the status quo and itsvarious manifestations: patriarchy,consumerism, commodification, etc. Toliberate the individual within, readers must embrace the language of nonsense,which, according to linguist Brian McHale, allows us “to project on to theworld of human culture a map for the reader to read himself or herself into. ..for finding our ‘selves’ in the hyperspace of postmodern culture.”

The poetry ofCharles Bernstein, rich with humorous nonsense, demonstrates how nonsense canfunction as an act of resistance. Bernstein, whom many critics consider the leading voice of the nonsensemovement, achieves his poetic aim by blurring the grammatical categories of theEnglish language and by violating our expectations of literary cohesion. In the resulting melee, Bernstein introducesa playful postmodern paradox, inviting the reader to construct meaning fromtext that constantly deconstructs itself.

Blendingdisparate and seemingly exclusive discourse styles, lexical choices, andphrases, Bernstein draws on the idea, articulated in his own poetics, that apoem “work at angles to the strong tidal pull of an expected sequence of asentence. . .giving two vectors at once--the anticipated projection underneathand the actual wording above.” Subvertingour expectation that literature cohere to a consistent theme, world, or voice,Bernstein challenges the long tradition of mimetic literature, presentinginstead the premise that a text conveys meaning by our acquiescence.

In the poem “LiveActs,” for example, grammatical ambiguities force the reader to makeinterpretive choices, a process that begins with the title itself. “Live” might function as an adjective,modifying “acts” and suggesting a theatrical moment, perhaps a stageperformance in real-time. Interpreted asa verb, however, “live” acquires a tone of command, spurring readers to embracea lifestyle philosophy. Depending on ourinterpretation, we might expect either a description of an entertainment eventor a self-help treatise. As we readfurther, a mishmash of different registers stumps our ability to discern asingle speaker behind the poem. Elevatedand colloquial diction derives alternately from Latin and Anglo Saxon; wordssuch as “redaction,” “somnambulance,” and “aquafloral” mix haphazardly with“hideaway,” “get,” and “cups.” Suchdevices blur the boundaries between discourse registers. “Live Acts,” placing under the umbrella ofone text a range of expressive styles, contains all the speakers associatedwith those styles. We have not onespeaker but several, or perhaps none at all, as they seem to cancel each otherout. The reader can choose whichvoice--one, none, or all--to accentuate, and thus consciously participate inthe constructivist process of representation.

Where “Live Acts”calls attention to this process on the level of voice, the poem “WhoseLanguage” invites the reader to participate in the creation of setting. The poem, juxtaposing literal and figurativeelements in a way that confuses the identity of either, presents a world thatresists coherence to a sensible or expected point of reference:

. . .The door

Closes on a dream of default and

Denunciation (go get those piazzas),

Hankering after frozen (prose) ambiance

(ambivalence). Doorsto fall in, bells to dust,

Nuances to circumscribe. . .

Here Bernstein creates a metaphor--doors do not literallyclose on dreams--but the metaphor quickly dissolves, as its vehicle (“dream”) acquiresliteral qualities, since the verb “hankering” complements it and gives it anagentive role. Normally, agentive nounsdenote sentient, tangible beings--things capable of taking action. “Dream,” in the context of “hankering,”achieves a literal, sentient quality, masking the figurative role typical ofmetaphor. Rather, any figurative role itretains happens by reader consent. Itfunctions, in effect, as a free-floating signifier, awaiting a reader to grantit literal or non-literal meaning. Realizing this, we might question our awareness of “door.” Normally, the noun denotes a literal object;however, doors do not close by themselves, as the door in the poem appearsto. We know this linguistically becauseits position in the sentence--the noun phrase to the left of the verb--normallycorrelates with agent. Thus, we cannotsimply categorize “door” as the literal half of the metaphor, since itfunctions both literally and figuratively as a door and an agentive being. Bernstein continues this process through therest of the passage: “ambiance,” normally denoting something atmospheric andintangible, in this case achieves solidity--the adjective “frozen” describesit. Similarly, the parallelism Bernsteincreates between “doors,” “bells,” and “nuances” suggests some type ofequivalency between the nouns---we can conclude that “nuances,” functioning asa parallel to “doors” and “bells,” also denotes something tangible, though suchinterpretation defies convention.

In sum, thepoem’s ambiguities--the blurring of the literal and the figurative, theequating of the intangible with the tangible--produce a world comprehended onlythough unconventional frames of reference. But the unconventional proves liberating, allowing us to accept thestrange sequential logic of the poem’s second sentence, “The dust descends andthe skylight caves in,” which counters our normal understanding of cause andeffect (we might expect dust to descend in the aftermath of a skylight cavingin, but not concurrently). Interestingly, once we dismiss our expectations of cause and effect, werealize the sentence never encouraged any in the first place--the subordinatingconjunction “as” implies only that one thing happened concurrently with theother; it is our readerly expectations that force a relationship betweenthem. We realize that the cohesion of atext to the outside world derives not intrinsically from language but ratherreader agreement. By rendering thisagreement conscious, via poems which resist unconscious assimilation toexpected frames of reference, Bernstein places the reader in the postmodernposition of seeing language as a meaning-making medium, rather than ameaning-containing package.

Using linguisticsto investigate the postmodern aspects of Bernstein’s poetry pays Bernstein thehonor of close study. Some mightadditionally investigate how language poetry violates speech act theory,particularly the maxims of relevance and manner, creating texts which subvertstandard communication procedure. Others might investigate the poemsphonetically, exploring what some scholars consider the poems’ musicalwording. Whatever the focus, suchinquiries inevitably dwell on the linguistic fabric of the poems rather thantheir content, an emphasis that recognizes a fundamental aspect of thepoetry: medium provides message. How we react to this depends on how much weembrace the postmodern relish for ambiguity, which Bernstein happily fulfills,granting multiple possibilities for play. Thus, “Live” in the title “Live Acts” shuffles constantly betweenadjective and verb; “I” in the poem “Wait” shuffles unresolved between firstperson pronoun and third-person character name; and the metaphor in “WhoseLanguage” continually deconstructs itself, as we decide which noun to label asfigurative and which to label literal. In the resulting nonsense, the reader finds the freedom that derivesfrom conscious, active participation in the meaning game.

Examininglanguage poetry on a theoretical level proves easier than assessing the genre’spractical impact. To say language poetryoccupies an obscure niche of the literary world overstates its footprint. The realm of anonymity in which most writersreside turns almost invisible in the neighborhood of language poets. Most readers who discover the genre credit(or blame) academia, specifically graduate-level English programs, where thelanguage poets’ metacognitive antics find a friendly reception among facultyheavily influenced by Derrida’s impact on discourse theory. An enclave of the esoteric, the place knownfor producing dissertations nobody reads about literature few understand tendsto glorify expression unsuitable for mainstream consumption. But even English departments exercise cautionin their approach to language poetry, treating it as a curiosity best reservedfor graduate seminars and students versed in postmodern tropes. For most students, such seminars mark thebeginning and end of their involvement with the genre. A small percentage might write papers aboutit, and of those, a select few might present at conferences. The number of people who actually read it forfun might fill a cozy restaurant booth. Tonearby patrons, the conversation at this hypothetical gathering might wellsound like gibberish.

In my view, thefailure of language poetry to gain mainstream acceptance says more about thelimitation of the mainstream than the proficiency of poets. Most readers, especially those with attentionspans limited by point-and-click culture, feel little inclination for the metacognitiveleap required by conscious participation in the meaning game. Readers want texts to communicate content,and while literary texts might “tell it slant,” readers don’t want to fixate somuch on the package that they can’t discern what’s inside. Put another way, mainstream readers preferpassivity instead of partnership, message instead of metacognition. They don’t want to render opaque a mediumfrom which they expect clarity. Hereinlies the paradox of language poetry: themore the genre asserts its poetic devices, the more it alienates those whom itseeks to liberate. Artistically, thelanguage poet treads upon a knife edge, where the appreciation of nonsensedepends on the preservation of sense. Asserting the primacy of the poem risks linguistic mayhem. Catering to the demands of the mainstreamrisks a bland text incapable of provoking postmodern metacognitivepartnership. Step too far in either directionand the artifact dissolves.

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-469750017 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

January 1, 2022

Perfect or Perfectly Deadly? Sumatra 2014

A jungle trek leads to a hidden cove

A jungle trek leads to a hidden cove

With a bit of gumption, a daypack of provisions, and a liberal application of bug repellent, the intrepid surf explorer eager to impersonate Indiana Jones can enter the jungle, struggle through suffocating humidity, and emerge from muddy paths to find a place where the constraints of ordinary experience not only diminish but give way to paradise visions. One may find, for example, a deserted cove where untrodden sand edges an emerald sea and balmy breezes carry an echo of the dreamtime. There, an apparently perfect left spins beyond the lagoon, a fantasy wave, its shoreward surge like the frolic of a winged horse in a meadow of the gods.

Sumatran secret. . .Photo: S. Jacques Stratton

Sumatran secret. . .Photo: S. Jacques Stratton When I first saw the wave it seemed surreal, as though the jungle trek had somehow warped the fabric of space-time and confronted me with a scene from the primordial Earth. Under the sheen of sweat and bug repellent coating my face, I felt my expression contort into that wide-eyed, open-mouthed variety that signals bewilderment. During the run of swell over the prior week, charter yacht crowds battled for waves half as good. To find a dream wave going off under the radar screen on a day deemed flat seemed beyond strange. Additionally, the irony had a personal dimension that turned more cruel with each successive wave that spun down the reef. I didn't have a board. . .

Why would I? Enlisted me on a jungle trek to photograph monkeys, I planned my equipment needs

Mystery monkey. . .Photo: S. Jacques Stratton

Mystery monkey. . .Photo: S. Jacques Stratton

With the call of the sea in my anxious expression, I absolved myself of further wildlife photography duties and made a beeline for camp, contemplating the sense of foolishness that would no doubt afflict me if, after slogging back and forth through the jungle, I returned board-in-hand only to find the vision of fantasy surf shattered by different tide and wind conditions. I'd heard tales of Indonesian reefs that, once in a Blue Moon, turned on as tidal forces pushed water over special coral contours, and I wondered if this spot might fit that profile. My mind a-whirl with such speculations, I lost an appreciation for potential trail hazards, including a brown snake whose presence I discerned just as my sandaled feet stepped inches from its flicking tongue.

Back at the camp, a profusion of empty beer bottles and the lethargic sprawl of my fellow guests indicated I'd have difficulty generating interest in a formally organized surf expedition. Specifically, I hoped to drum up a skiff and a surf guide, and thus avoid returning on foot to the surf. Unfortunately, the camp crew had all embarked on errands, and the most interest I could generate in my fellow campers was a bemused "good on ya, mate!" from an Australian, who clearly regarded my report of perfect surf on the other side of the island as a madman's raving.

After another jungle jaunt that depleted a good portion of the calories I needed for surfing, I returned to the hidden cove. With a cackle of glee I mocked the unbelievers back at camp. "I'm out there!" I intoned, as the surf gods unfurled another set for my private appreciation.

"I'm out there!. . .In truth, I had no sense of the wave height.

"I'm out there!. . .In truth, I had no sense of the wave height.The paddle-out went easily enough--at first. Between the beach and the fringing reef, a waist-deep lagoon, its clear waters a sanctuary for colorful fish, offered an inviting paddling path. Yet here I encountered a surprise indication that I'd stumbled upon the primordial edge, where expected forms acquire unexpected dimension. The lagoon proved wider than I initially judged--much wider. When I finally reached the shallows of the fringing reef and stood on the coral, I looked back to see palm trees as twigs on a distant beach. The surprise width of the lagoon foreshadowed the surprise width of the reef, whose sharp corrugations I now traversed carefully, treading my booties through a minefield of urchins, anemones, fire coral, and other toxic terrors. Eventually, I reached the point where the bubbly aftermath of the oncoming waves surged against my shins, and there discovered another surprise: what from the beach looked like playful splashes of foam resolved, upon closer inspection, into hissing whitewater cauldrons powerful enough to blast me off my feet. "Holy s--t!" I muttered to myself. "It's bigger than I thought." Rather than pause to reassess the situation, I let my enthusiasm override my caution and took advantage of a lull to paddled hurriedly seaward, angling toward the take-off area. Lured fully into the surf zone, I finally understood why I had such difficulty determining wave height from the beach. Off the headland, a dark shadow formed in the sea, after which a great suction of water dredged off the shallows, leaving the reef almost dry. Where shadow and suction met, a lip pitched forward, impacting below sea level just inches from the exposed coral. Invisible from the beach, the full scope of this dynamic did not reveal itself until witnessed from a waterfront seat.

Perfect, or perfectly deadly? That lip is impacting below sea level, inches from exposed coral. Photo: S. Jacques Stratton

Perfect, or perfectly deadly? That lip is impacting below sea level, inches from exposed coral. Photo: S. Jacques StrattonDriven more by a sense of showmanship than a real interest in riding the dredging demons, I waited on the periphery, hoping an amiable shoulder would offer an entry point that didn't entail a vision of my body impaled upon coral heads. That game soon ended when I padded for, backed out of, and nearly got sucked over the falls on a wave I initially judged as head high but which morphed into a 10' face. Deciding to make discretion the better part of valor, I made my way back to the beach. It's out there, if you want it--the jungle path, the hidden cove, the perfect (and perhaps perfectly deadly) wave. You won't know until you go. My advice: bring a helmet, and don't surf alone.

October 5, 2021

Taste, Anti-taste, and the Ethos of Beer

Since my college days, I’ve enjoyed a relationship with beer that, if not passionate, entails more than casual affinity. I hesitate to call myself an aficionado because I’ve never undergone the rites of passage—the purchase of homebrew equipment, the understanding of brewing nomenclature, the European vacation planned around Oktoberfest—that signify enthusiasm in the devotee. I do, however, feel deprived if more than a day or two passes without the happy fizz of a Deschute’s Inversion IPA upon my palate, and I often crack open a “cold one” mid-afternoon, justifying my behavior with the excuse, popularized in song by Jimmy Buffet, that “it’s five o’clock somewhere.” Though Twelve-Steppers might regard this as a sign of more troubling alcohol habits, I contend it simply means I recognize beer’s prominence in the hierarchy of beverages. Moreover, the true alcoholic, whose pickled brain requires ever greater quantities of drink to produce the desired level of intoxication, eschews beer for high-octane alternatives like vodka, whiskey, and other potent distillations. In other words, true alcoholics go for the hard stuff.

If I lack the blind devotion of serious fans, I still possess sufficient ardor that I voice only a meek complaint against the abuses inflicted upon today’s beer drinker by the “Lords of the Vat”—a phrase I borrow from James Joyce and apply to the increasing number of American microbreweries charging increasingly outrageous prices for increasingly stranger brews. I willingly suffer the extortion of paying ten to twelve dollars for a six-pack that just a few years ago retailed for half as much, and tolerate as experiments in creativity the undrinkable concoctions invading supermarket beer aisles—the hazy IPAs that curdle the tongue like rancid grapefruit juice, the mixed-fermentation fruit beers that require chewing before swallowing, the chocolate stouts that resemble specialty coffees at Starbucks more than something known as beer. I accept these abuses as growing pains that inevitably occur when a vibrant industry pushes the envelope of market capitalism, and console myself with the thought that hopheads today have more to cheer about than folks who endured the bland liquid of the pre-microbrew days, when names like Coors, Pabst, Miller and Michelob dominated the era of “American pisswater.”

Not that American pisswater lacks merit entirely. No less a spokesperson than Jim Morrison, who sang famously in “Roadhouse Blues” about waking up in the morning and getting himself a beer (or as Morrison crooned, “bee-yah”) promotes its virtues. In addition to offering a motto to frat-house partyers and counter-culture bohemians, Morrison articulated the ethos of America’s rock ‘n roll youth. We can reasonably infer that “bee-yah” doesn’t mean some namby-pamby microbrew or sophisticated European import; no, Morrison meant something cheap, canned, blue collar—Schlitz perhaps, or maybe Budweiser. And I suspect that once Morrison cracked open the can, he found the absence of taste—shall we say, the anti-taste—a suitable accompaniment to the nihilistic, unrefined, “end-is-always-near” mindset romanticized in rock ‘n roll. As teenagers, my friends and I referred to Budweiser as “Buttwiper,” a term meant to signify the product’s low quality and, by extension, our own lack of refinement. Of course, consciously or sub-consciously, we drank “Buttwiper” and its ilk precisely because it signified lack of refinement. If we dared consider something better, voices of derision rose from our peers to mock the idea. Any beer deemed too unique, too intellectual, or too European risked branding the drinker as uncool. And so we drank pisswater, not because we liked the taste, but because, channeling Morrison, the anti-taste suited our flannel-and-blue-jean personas.

Not until college, when I departed for a study-abroad semester in England, did I appreciate the idea that a beer might have delightful flavor and, properly sipped from a pint glass in a cozy pub, offer a refined drinking experience. To go from Buttwiper and its ilk to a pub-draught black-and-tan represented a transformation not just in degree but in kind, the beer equivalent of upgrading to a luxury suite after a stint in a flophouse. Like a mystical lava lamp, the layered cocktail—Guinness Stout floating atop an amber lode of Bass Ale—mesmerized me, a surprise made more pleasing by the discovery that an English pint measures twenty ounces, compared to the American sixteen. Happily, the sensory experience extended beyond the visuals. Passing from glass to mouth, the brew spread a wholesome ambrosia among the tastebuds, hinting at a bygone time when “liquid bread” restored vigor to the yeomen of Sherwood Forest. Enlightened by such fare, I came to understand how certain pubgoers, whom I initially stereotyped as bored retirees desperate for the consolation of drink, could spend an afternoon hunched over a pint. Such pubgoers, I realized, merited admiration, not admonishment.

Palate upgraded, I returned from England just as the American craft beer revolution started to go mainstream. Soon, my refrigerator featured a regular inventory of brands like Red Hook, Sierra Nevada, and perhaps that most mainstream of craft brewers, Sam Adams—an indulgent expense for an English major whose bookish sensibilities made for a generally anemic income. Yet though my spartan budget (decent paychecks eluded me until I graduated with my Master’s degree and began my teaching career) often relegated me to a ramen diet, I never wavered from my Commitment to Craft. This reflected not a Jim Morrison-inspired lifestyle expression, but rather a poetic appreciation of beauty. If Budweiser represented the ethos of rock ‘n roll, then craft brew, I believed, represented the ethos of sublime experience. The following anecdote from my college days provides an illustration. One evening, bolstered by my belief in the sublime quality of microbrew, I witnessed a moment of magic juxtaposed against the urban sprawl of Los Angeles. Frazzled from writing an explication of Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” for my Victorian Lit class, and depressed by the poem’s despondent final stanza, I toted an acoustic guitar and a six-pack of Red Nectar Ale (Humbolt Brewing’s ambrosial classic) to the Santa Monica Bluffs, thinking to serenade the sunset and take a break from Matthew Arnold’s intellect. In disregard of the traffic on PCH, whose noise reminded me of the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” lamented by Arnold in his poem, I plucked an upbeat arpeggio, gulping mouthfuls of Red Nectar between chord progressions. Of course, as anyone familiar with the Santa Monica Bluffs might predict, this bacchanal summoned from the shadows several representatives of the area’s homeless population, one of whom, a noxious fellow in torn denim and flannel, invited himself to a seat on my bench. After inquiring if I might spare a bottle, the man turned his eye toward the guitar. Annoyed, I grudgingly allowed him to strum a tune, but soon appreciated the fortuitous quality of the moment: as the interloper slurped his suds and attempted a rasping rendition of “Proud Mary,” I watched the last rays of the sunset paint the horizon with a neon glow that culminated in a burst of vermillion—the fabled “green flash” of urban lore. Though several variables combined to make me a witness to the event, I believe the microbrew played a significant role, and to this day, influenced by nostalgia as much as taste, I buy Red Nectar when I chance upon it.

But. . .fast forward to 2021. As with so much rendered uncertain in a time of pandemic, my microbrew mania revealed its shortcomings as a guiding creed. At a friend’s July birthday party, craving refreshment after some fellow attendees goaded me into a hacky-sack competition, I found myself drinking keg beer from a plastic cup. Something about the taste—or rather, the curious absence of taste—allowed the delightful contrast of cold beer on a hot day to reach its full potential, quenching my thirst with efficiency. As I drained my cup, each gulp brought an echo of memories I couldn’t quite place. Intrigued and perplexed, I asked the host what brand of beer the keg contained.

“Budweiser,” he informed me, somewhat apologetically. “Some folks call it American pisswater, but it goes down smooth on a hot day.”

“Pisswater, huh?” I mused, refilling my cup. Gleaming in the summer sun, the keg resembled a silver totem, and I regarded with newfound appreciation the liquid it dispensed. Buttwiper never seemed so good.

July 21, 2021

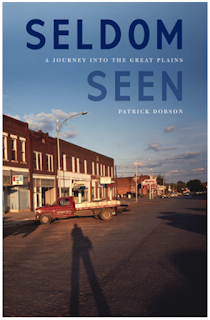

An Open Heart for the Open Road: Praise for SELDOM SEEN by Patrick Dobson

On the eve of his departure for a months-long backpacking road trip through the Great Plains, Patrick Dobson attempts to reassure his friends, who consider him foolhardy for setting off without the protection of a gun. “I want to meet people, not shoot them,” he declares, coining a phrase that, as his journey progresses, comes to represent a manifesto for open-hearted travel.

Propelled by leg power and the kindness of passing drivers, whose vehicles provide timely solace from hailstorms, dangerous stretches of highway, and bouts of exhaustion, Dobson meanders from Kansas City, MO to Helena, MT, hoping to meld with the landscape in a way that only slow travel can achieve. As Dobson explains, “I wanted to move slower, to feel the distance and lose myself in it. I wanted to know the plains more deeply than from conversations with strangers filling the gas tank or coffee thermos. With decent shoes and a backpack I would become familiar with the scenery and its people. I wouldn’t hitchhike. I would need no gas stations or interstates. I offered a ride, I would take it, but no further than the distance of a day’s walk. That was enough.”

The motive for Dobson’s wanderlust-- the frustration of working a dead-end job and growing complacent in a robotic routine—will resonate with anyone stuck in, numbed by, or otherwise dispirited with the workaday treadmill. Throughout the book, the quest to find the soul of the prairie, and belief in the redemptive power of that soul, raises a hopeful counterpoint to the decaying towns and hardscrabble lives (i.e., the “Seldom Seen”) that dot the grasslands. We root for the author because we want to believe in the merits of his journey, and verify the idea escaping drudgery requires only courage and an open heart for the open road. At its core, the narrative underscores this idea; each new chapter brings a catharsis as, like flowers waiting to bloom, the people and places Dobson encounters open up to him, as if his desire to break free catalyzes their own spirit potential. Additionally, we root for Dobson because his vulnerabilities remind us of our own struggles. Hints of backstory reveal humanizing angst: though highly educated, Dobson works a job unsuited to his skillset; a recovering alcoholic, he fights the demons that cost him time and relationships; a caring father, he seeks greater involvement in the life of his little girl, but his ex and his wanderlust thwart a closer connection. Ultimately, the psychological dimensions of the journey rival the physical dimensions, immersing the reader in a man-vs.-self conflict that, by the end of the book, brings the recognition that embracing humanity means relishing its dichotomies—“its mediocrity and beauty and ugliness, meanness and generosity, sadness and pain and joy.”

Rich with detail, the narrative proceeds quickly, with crisp descriptions (“Casper looked like a town that need a bath and a shave”) and deft use of storytelling tactics—active voice phrasings, appeal to the senses, and three-dimensional characters. Though limited to cameo appearances that rarely last more than a chapter, the characters Dobson encounters display quirks and attributes that infuse the tale with intrigue, making the prairie’s flat horizon come alive with multi-dimensional possibilities. At times, these characters serve as foils, conversational counterpoints by which Dobson refines and articulates his road-trip philosophy. In other instances, they show that behind small town facades lurk interesting oddities: a frustrated housewife who attempts to seduce the author while her husband sleeps in the other room; a misanthropic van-dweller who prefers the companionship of cats to the injustices (whether real or imagined) of people; a front desk clerk who moonlights as philosopher, dispensing enlightened commentary about human nature.

In a travelogue that spans a range of places and people, some experiences inevitably leave Dobson with a bitter taste. At a rodeo in touristy Jackson, Wyoming, an accident inflicts grave injuries on a contestant. The incident makes Dobson lament the random cruelties that society tolerates for the sake of profit. As disparaging thoughts about the rodeo owners and their tourist customers loop through his mind, Dobson feels a sense of guilt that inspires a longing for loving connections: “I hated myself for my part in putting that kid in danger. I had bought the ticket and been one of the spectators. I had been part of it. . .I wanted to go home and be with my daughter. Who was I kidding? Traveling across the country? To do what? To do what?” Such moments of self-doubt not only render Dobson a more authentic narrator but remind us that setting out on the road sometimes results in a more cherished notion of home.

Travel literature, like travel itself, impacts us most when it opens the door to discovery. Though set in America’s backyard, Seldom Seen takes the reader on a journey that encourages a fresh view of the Heartland. Along the way, it inspires us to open our hearts to the open road, and find what curiosities await in the geographies we call home.

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073697537 9 0 511 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

October 13, 2020

Notes from a Foray into Manuscript Editing

--How I Affirmed my Attitude toward Adverbs--

One might suppose that an English teacher with twenty-five years’ experience grading college essays—a type of “manuscript,” granting the term a liberal interpretation—can muster the aesthetic sense necessary to guide a book-length project from draft to completion. The supposition presumes situational similarities that actual experience reveals as illusory. Books, artistic works intended for a marketplace, differ in fundamental ways from essays written for a grade, and the gatekeeper role played by an editor entails a level of involvement that professors, for practical reasons, rarely embrace. An editor has a vested interest in the success of a book, even a book with narrow audience appeal. An English teacher, by contrast, rarely feels personal failure when students submit disappointing work, and in the interest of university standards, may relish the opportunity to disparage a paper’s “errors.”

I bring this up not to praise editors, who for all their efforts frequently release crappy books into the marketplace, nor to criticize English teachers, who despite their red-ink raptures frequently inflate grades, but to provide a context for my recent foray into manuscript editing, an experience which gave me a new perspective on the creative process.

First, a bit of background. . . as newbie authors often do with a freshly published book, I regaled friends and acquaintances with copies of my travel memoir, Islands on the Fringe. One such friend, Rancroft Beachley, whom I met in graduate school in 1995, took the gesture as an invitation to divulge that he too had a book in the works. Would I mind taking a look at the manuscript, he wondered? A communications director with a long list of technical writing credits, Rancroft boasts an impressive curriculum vitae and I felt genuine curiosity about his creative endeavors. Expecting a polished product in little need of critique, I agreed, hardly suspecting what might transpire.

The work he proffered diverged so much from my expectation that I initially considered it a practical joke. The “manuscript” consisted of random scribblings, tangent-prone expositions, and experimental blends of poetry and prose. Collectively the mad missives recorded the insights and opinions of an investment club that Rancroft belonged to. Income investing, the conceptual ribbon that bound the bundle, provided the common denominator for the haphazard contents.

An English teacher by trade and an adventure traveler by passion, I felt unsuited for the project. I lacked both subject matter expertise and fluency with finance genre jargon. Eclectic and esoteric, the manuscript included academic explications on subjects like permanent capital equivalence (the amount of capital required to purchase something from dividends alone) to a bizarre musing on the merits of Sandra Bullock as a pin-up girl for a dividend campaign. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, something about the subject intrigued me, and the more I read the more I encountered fascinating passages that convinced me of the work’s potential. On this point Rancroft injected a dose of realism: “most people don’t have a clue about income investing. . .don’t expect anybody to actually read this stuff.”

If this backstory explains my involvement with the project, it glosses over an important detail—why I wanted to take a detour from my own creative projects to wordsmith a document that Rancroft assured me was destined for obscurity and would do little to boost my budding literary ambitions. An honest answer to this question probably requires the insight of a psychotherapist. Given to procrastination, I perhaps saw manuscript editing as a chance to toy with the writing process without really writing, in effect delaying the dirty work of starting my next book. Perhaps I believed the project could serve as a low-impact training exercise: applying an editor’s eye to Rancroft’s work would further hone my own revision process. Continuing the “training exercise” theme, I rationalized that just as athletes take to the golf course during off-season, so might a writer between books take to manuscript editing.

OK, so much for background. Mostly I recall what resulted from this low-impact training exercise. And here I feel more certain about the answer: I re-affirmed my attitude toward adverbs.

If writers consider their chief obligation the “truth” of their characters or subject matter, editors face the task of refining that truth into a consistently presentable form. Put another way, blissfully ignoring postmodern discourse theory, the writer pledges allegiance to the message, while the editor pledges allegiance to the medium. Frequently, this means relieving a text of the abuses heaped upon it by the author’s vanity. At times, I discovered it meant invoking the shield of conventionalism against Rancroft’s blurs of prose and poetry--while creative, these seemed too idiosyncratic for a finance text. At times, I discovered it meant deleting entire passages, the product of Rancroft’s enthusiasm for single malt scotch as a tool for philosophical insight (having utilized the tool somewhat excessively, he’d followed his muse a bit too far into conceptual back-alleys). For his part, Rancroft regarded these efforts with a bemused disinterest. But when I dared to critique an adverb, he grew indignant. He called me a member of the “Word Police,” an accusation with Orwellian overtones no doubt meant to insult me and my generally liberal politics.

The word at the center of this dispute was unprecedentedly. A multi-syllable menace festering at the core of the sentence “The 2008 financial crisis was unprecedentedly disruptive to retirement plans,” I found this word choice troubling. Really, a writer has no justification to inflict such six-syllable sadism on an unsuspecting reader.

“What’s wrong with that word?” Rancroft asked. “The 2008 financial crisis wasunprecedentedly disruptive!”

“That word,” I explained, summoning a patient professorial tone, “bombards the reader with a barrage of prefixes and suffixes that obscure the root meaning. Think about the linguistic machinations! From the verb precede, you’ve created a noun, precedent, which you then transform into the adjective precedented through the suffix “ed.” Then you add the prefix “un” to signal a negation of the adjective, and end the affair with another suffix, “ly,” engineering yet another transformation, this time into an adverb. It’s a multi-syllable mess unsuited to the short attention spans of today’s reader.”

“I don’t think it’s a big deal,” he insisted.

“Say it five times in rapid succession.”

“Unprecedentedly, unprecedentally, unprethedenly. . .”

His pronunciation pummeled by spittle and lisps, Rancroft began to see my point.

Creative writing teachers have a saying, “no discovery for the writer, no discovery for the reader.” By this they mean that a good text grows organically, evolving in ways unforeseen during the writer’s initial drafting process. Writers who know the progression of a manuscript from its first to last sentence and try to fit everything into a pre-planned outline will likely create an unremarkable text. By contrast, writers who follow the muse into regions of uncertainty may well discover something remarkable among the shadows (they’ll also discover a lot of trash, but that’s just how it goes). On a different level, I found this idea applicable to the editing process. Matters of sentence style I might normally overlook emerged as troublesome thorns. The organizational template I initially thought sensible later proved inadequate. Intriguingly, the emerging product differed from the initial vision. But most importantly, the process reaffirmed my aesthetic sense. For writers between projects, I recommend a foray into manuscript editing. If nothing else, it offers the potential to clarify one’s attitude toward adverbs. . .

(CA$H CRAFT: The Musings and Meditations of an Income Investor, by Rancroft Beachley, currently retails in paperback via Amazon)

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073697537 9 0 511 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.0in 1.0in 1.0in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</style></p>

September 28, 2020

Linguistics and the Meaning Game: A Treatise for Writing Teachers

Descartes, eager to define humans as entities distinct from the natural world, contended that language does not result from “natural movements which betray passions and may be imitated by machines as well as manifested by animals” (Chomsky). Crying, while a communicative act, does not constitute language; it merely denotes a response to stimuli. The phrase “I am sad,” by contrast, rises to the language level because it represents abstract self-awareness on a creative plane unaffected by stimuli. Much of Descartes’ comments, which tie inevitably to his philosophical writings, stem from the assumption that human thought—and by extension, human status—deserves commendation as something uniquely praiseworthy: “I think therefore I am!” Concerned with proving that animals and machines can’t be people, he left unexamined the complex relationship between language and ideology. The legacy of 20th Century linguistics encourages a view of language as a fascinating field in its own right and not merely a symptom of intelligence. (Moreover, insofar as scientists now apply the “language” label to behaviors across the animal kingdom, we might wonder if Descartes’ views amount to a form of species-ism.) I offer here an overview of three philosophies of grammar that derive from this legacy and comment briefly on their relevance to writing instruction.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand Saussure promoted a view of language which had significant consequences, by the 1960s and 1970s, to philosophy and creative arts. In brief, Saussure’s view held that language, and in turn thought, stemmed from a type of disruption, or as later philosophers termed it, “difference.” Saussure’s view emerged in contrast to the traditional quest through the 19th Century, by which scholars, seeking universal vocal sounds related to the real world, hoped to arrive at a fundamental description of language. Saussure argued that scholars pursued the quest in vain, for human language offers only one constant: the interplay of consonants and vowels. Extrapolating further, Saussure argued that without such interplay—and not just between vowels and consonants, but between all sounds recognized by the mind as phonemes (in their simplest form, the letters of the alphabet)—language would cease to function. We recognize the sound denoted by “R,” for example, not by R’s innate qualities, but by its contrast to “S” and “Q” and other basic sounds. This description represents an auditory parallel to the way we think about the world on an ideological level. We know “sky” not because of its singular presence, but because of its boundary with earth and sea. According to Saussure, our language structure, as well as our conceptual view of the world, thus depends fundamentally on the difference between entities.

People who remember grade school English class as a series of grammar drills meant to identify parts of speech or diagram a sentence participated in a style of instruction influenced by Saussure. The concept that we can break a sentence into articles, nouns, verbs, prepositions, and adjectives implies that we can recognize the difference between such units and also that we know the syntactic instances in which one unit (and not another) may occur. No matter how complex the sentence, we can reduce it to fundamental units. This premise, a structuralist notion, provides the origin for the grammar known as “case-slot.” To adherents of this school, Thomas Paine’s famous sentence These are the times that try men’s souls breaks down into syntactic slots (subject, verb, object, dependent clause) and the cases to fill those slots.

Dedicated to the idea that the building blocks of language fit into certain structures but not others, case-slot grammar gives English teachers unafraid of appearing dour, prim, and snobbish a chance to enforce “The Queen’s English” via prescriptive rules. Apostrophe ‘S, as a basic unit, cannot precede the noun for which it bestows the quality of possession. . . the object of a preposition can’t be the subject of a sentence. . .etc.

The “whole language” fad which took hold in the 1990’s, along with Humanities professors’ unquestioned fascination for Derrida and Postmodernism, drove a wrecking-ball into structuralist notions like case-slot. In his landmark essay Structure, Sign and Play . . ., Derrida argued that because we have no adequate definition or intrinsic awareness of difference—we can only define it by recourse to itself or perceive it in the presence of other things—a paradox arises. Basing knowledge upon something intrinsically unknowable destabilizes both language and knowledge. How can words have meaning—or at least an “official” structured meaning—when at the center of the meaning game lies an entity not clearly defined? Humanities departments throughout academia still resonate with the implications of this “postmodern condition.”

During the 1950s and 1960s, in the context of Cold War politics that brought tremendous funding to the sciences, another philosophy of grammar, transformational/generative linguistics, emerged as the darling theory among American linguists, largely through the work of Noam Chomsky. Chomsky’s name echoes with guru status not only in linguistics but also political science and social commentary, and much as Chomsky branched into other fields, so did generative linguistics spread out of the academic community into applications such as artificial intelligence. Perhaps the appeal of generative grammar lies in its somewhat “scientific” quality: based on observations, it seeks to predict language phenomena. Further, it offers a convenient explanation for the way children acquire language. Noting that children move rapidly from speaking single words to speaking entire sentences, Chomsky and his adherents speculated that a pattern, a set of templates, resides within the human mind. According to Chomsky, we learn language not by imitating, but by matching the patterns we hear to the master template in our minds.

Language, to the generative linguist, refers to a pattern organized by a set of formulas. The formulas derive from a master template, and the words we speak and the sentences we write comprise transformations of the template, a surface reflecting a “deep structure” underneath. Thomas Paine’s famous sentence reflects a transformation of two deep structure statements: Certain times try men’s souls + These are the times. The surface sentence “These are the times that try men’s souls” adheres to a formula allowing the combination of two sentences into one through the generation of a relative clause. Sentence-combining exercises, for years a regular activity in grade school English classes, trace their origin to transformational grammar.

While Generative linguistics does much to explain the process of language acquisition, the concept of an internal template ignores the influential effect that culture, environment, and belief have upon actual language use. Critics of the generative model often argue that language is only partly internal. More accurately, such critics contend, language and culture describe a circle of influence upon each other: born into culture, we depend upon cultural values for our perception of meaning. The cultural influence upon language, known as ideology, serves as the launching point for the third major approach to language: functional grammar.

Largely developed through the work of linguist Michael Halliday, functional grammar proceeds from the premise that any description of language must include a description of context, the surroundings in which language has meaning. Further, functional grammar assumes that at all times users of language have choice, in the words they use, in the sentence structures they select, etc. As such, language amounts to a form of behavior. Intriguingly, functional grammar asserts that meaning (thought) fundamentally links to language. We do not wrap thoughts in language—rather, what we think IS our language. Medium and message comprise flipsides of the same communicative act.

In this view, Thomas Paine’s famous sentence “These are the times that try men’s souls” operates on three levels of meaning: ideation (i.e. what the speaker depicts as action), theme (i.e. what the speaker makes the sentence about), and interpersonal (i.e. how the speaker links the sentence to an ongoing conversation with a larger community). The main verb, “are,” suggests a state of identification equating one concept with another. Conceivably, Thomas Paine could have said “These times agitate us,” choosing a verb of process rather than static existence. A similar choice underlies what the sentence asserts thematically. The pronoun “these,” referring to “times,” emphasizes circumstances rather than humans. Further, the circumstances do the action—stylistically, Thomas Paine communicates that humans are the victims of an environment outside their control.

Functional grammar offers a rich resource for writing instructors. For one, it suggests that all aspects of communication, from the sciences to the humanities, derive from ideology. Further, leading students to question ideology encourages critical thinking. Asking students to compare phrases like “Fire fighter” and “freedom fighter”—structurally similar expressions with divergent interpretations—helps show that we do, in fact, speak ideologically. How do we know that one “fighter” fights against fire while the other fights for freedom? Culture tells us, imbuing “freedom” with such a positive connotation that we automatically assume the “freedom fighter” must strive to promote it. Similarly, if we can say “it’s raining” to indicate a sky filled with water drops, can we say “it’s winging” to indicate a sky filled with birds? The fact that English speakers recognize the sense of the former but not the latter reflects cultural biases that refuse to accept birds as a weather phenomenon.

Much to the detriment of creative writing majors, very few creative writing courses at the undergraduate level incorporate a formal study of linguistics into their curriculum. Consequently, colleges across the nation each year graduate thousands of aspiring writers who possess only a rudimentary awareness of the meaning game. Some of them may boast portfolios of entertaining short stories polished through the classic workshop approach long regarded as a staple of the writing classroom, but very few have sufficient fluency in discourse theory to understand how a text makes meaning. To raise a point that some may regard as trivial but I consider highly pertinent, how many creative writing students understand speech act theory? Writing teachers obsess over authentic dialogue, and assign texts that model characters speaking authentically, yet very few of these teachers (and even fewer students) know about Grice’s Maxims, a famous tool for the linguistic study of conversation (and the perception of text as a conversational act).

An ideologically informed approach to writing instruction would emphasize the HOW of a text as much as the what. . .in other words, it looks at the medium as much as the message. Linguistics offers a valuable toolkit for developing a more robust awareness of text. In my view, the “functional grammar” of Halliday holds the most potential, but any formal linguistic represents an improvement over current practice. Unless undergraduate creative writing programs place a greater emphasis on linguistics in their curriculum, they will continue to graduate writers who fixate on message without a full grasp of the medium.