Kenneth L. Gentry Jr.'s Blog, page 34

August 26, 2022

NATIONAL BORDERS & THE BIBLE

PMW 2022-064 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2022-064 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

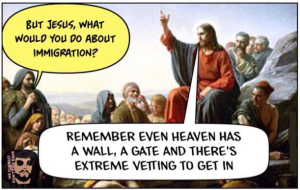

The collapsing border disaster under the Biden Maladministration is a live topic of international consequence today. Many well meaning Christians believe it is wrong to keep refugees out on a temporary basis because they believe borders are man-made constructs lacking biblical warrant. Besides the contradiction obvious in their having homes with walls and locked doors, their argument does not hold.

Established borders are biblically warranted as we see in two clear scriptural examples. Though other arguments are available, these are quite potent.

First, the garden of Eden.

The garden was distinct from the rest of the world, which meant something must have distinguished it from the broader world. God created Adam then “placed” him in (Gen. 2:8) / “took” him to (Gen. 2:15) the garden.

Then when Adam sinned, God “drove the man out; and at the east of the garden of Eden He stationed the cherubim and the flaming sword which turned every direction to guard the way to the tree of life” (Gen. 3:24). From this point on, Adam was not forbidden to dwell in the rest of the world, but only in the specific, guarded region of Eden. Eden had borders.

Second, the promised land.

The promised land had God-designated boundaries (Num. 34). God’s special ritual laws for “the land” (such as the Jubilee law) prevailed within this border-defined region.

Political Issues Made Easy

Political Issues Made Easy

by Kenneth Gentry

Christian principles applied to practical political issues, including the importance of borders, the biblical warrant for “lesser-of-evils” voting, and more. A manual to help establish a fundamentally biblical approach to politics. Impressively thorough yet concise.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

In his commentary on Leviticus (pp. 423, 424) Gary North writes:

The Israelites “would police the land’s boundaries, keeping stranger’s out except on God’s terms.” “To be a perfect stranger to the covenant-breaking world outside the geographical boundaries of Israel . . . “ “For as long as they dwelt within the land’s geographical boundaries under the terms of the original distribution, Israelites had to keep strangers from inheriting agricultural land.”

Nations have legitimate needs for borders, just as cities and counties do for purposes of police jurisdiction, taxation determination, judicial administration, and so forth. No one in Greenville, SC, likes it when a policeman from Juarez, Mexico, pulls them over on I-385 for lacking a proper license tag. Nor are we pleased when a tourist from Gaborone, Botswana, votes in our Presidential election.

And in a world of sinners, those borders need to be protected — as we see in principle from Adam’s original expulsion from the borders of the garden.

Israel had God-defined borders to a particular land area that God gave them (Num. 34:2ff). The means by which God gave it was through war (Deut. 7:1–2, 16-24). God commanded that the Canaanites driven out “shall not live in your land” (Exo. 23:33). Obviously, the Canaanite response would be to try to retake their land, against which determination Israel must protect it (i.e., the land within her borders, Exo. 23:27-31; Deut. 28:7).

Israel’s borders were God-defined, she was given a particular land, and no other. Therefore, she was not to engage in foreign wars of land acquisition. But her warning from God was that if she did not obey God’s covenant: “The LORD shall cause you to be defeated before your enemies; you will go out one way against them, but you will flee seven ways before them, and you will be an example of terror to all the kingdoms of the earth” (Deut. 28:25). These would be invading enemies, enemies from outside the land (Deut. 28:32-33, 47-50). Therefore, Israel would be in danger of being taken from her God-defined land (Deut. 28:36, 41, 63-65). Her danger of being conquered would be a danger “throughout your land” (Deut. 28:52) in “all your towns” (Deut. 28:55, 57).

God’s Law Made Easy (by Ken Gentry)

God’s Law Made Easy (by Ken Gentry)

Summary for the case for the continuing relevance of God’s Law. A helpful summary of the argument from Greg L. Bahnsen’s Theonomy in Christian Ethics.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Just as Israel would have her own borders, the Bible recognizes that other nations have borders, such as the Edomites (Num. 20:23), the Amorites (Num. 21:13), and the Moabites (Num. 21:15). The Israelites recognized those borders and sought permission to “pass through your land” (Num. 21:22). Israel would expect the same for her borders.

And I did not even mention heaven’s “gates,” an image demonstrating God’s keeping intruders out while his people are safe within (Matt. 7:13–14; 16:18; Rev. 21:12-15; 22:14). Nor the gates of the temple walls (Eze. 10:18; 40:5-8). In a world filled with sinners, borders, walls, and gates are essential for well-being.

At the height of the advance of the kingdom or in the eternal realm people will be able to leave their gates open and unattended: “Your gates will be open continually; They will not be closed day or night, So that men may bring to you the wealth of the nations, With their kings led in procession” (Isa. 60:11). But until then . . . gates and borders are a necessity in a fallen world.

August 23, 2022

THE 10 COMMANDMENTS AND DEUTERONOMY

PMW 2022-063 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2022-063 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

A casual reading of chapters 5 and following of Deuteronomy appears to present a random collection of laws. Yet a fairly widespread scholarly consensus discerns a basic organizing principle: these “randon” laws follow the order of the ten commandments.

In this, the largest section of Deuteronomy, Moses provides the commandments’ broader implications by offering practical applications (cf. Deut. 1:5). Though the outline is not overtly presented by Moses, given Moses’s orderly mind and compositional skills, along with the outline’s general fit, it is strongly suggested. We must understand also that since the law comes from one God and is unified many overlaps and inter-relationships exist between the commandments.

The first four commandments

The first commandment (Deut. 5:7) highlights God’s unique and absolute authority. It is developed in Deut. 6:1–11:32. This section exhorts love of God (e.g., 6:5) and obedience to him (e.g., 6:6). For example, it warns against testing him (e.g., 6:16), reminds Israel that God is worthy of respect (e.g., 7:6–8), and proclaims God’s blessings for obeying him (Deut. 11:1–32).

God’s Law Made Easy (by Ken Gentry)

Summary for the case for the continuing relevance of God’s Law. A helpful summary of the argument from Greg L. Bahnsen’s Theonomy in Christian Ethics.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The second commandment (Deut. 5:8–10) emphasizes God’s dignity, especially in worship. It is expanded on in Deut. 12:1–32. For example, in discouraging the adoption of Canaanite religious altars and worship practices (12:1–3), Israel must follow God’s priestly system and establish a central, unified sanctuary in the land to protect her worship of the one true God (12:4–32).

The third commandment (Deut. 5:11) presses the importance of God’s name, calling on Israel to be serious in her relationship with him. This is covered in Deut. 13:1–14:21. For example, this section condemns false prophets (13:1–18), which are a test of the Israel’s commitment to God alone. It also reminds her to keep his dietary laws in demonstrating her distinctive commitment to him even in the mundane things of life (14:1–21).

The fourth commandment (Deut. 5:12–15) requires observing the sabbath in demonstrating thanks to God for his deliverance (Deut. 5:15) and for his good gift of creation (Exo. 20:11). It is applied in Deut. 14:22–16:17. For example, this section calls for thanking God by faithfully tithing to him (14:22–29) and keeping sabbath years (15:1–18) and the special national feasts of celebration (16:1–17).

The last six commandments

The fifth commandment (Deut. 5:16) highlights the proper exercise of human authority, requiring that it conform to God’s will. It is covered in Deut. 16:18–18:22. For example, this section highlights various levels of authority beyond its starting point in parental authority. It discusses judges (17:2–7), kings (17:14–20), priests/Levites (18:1–8), and prophets (18:9–22).

Standard Bearer: Festschrift for Greg Bahnsen (ed. by Steve Schlissel)

Includes two chapters by Gentry on Revelation and theonomy. Also chapters on apologetics, politics, ecclesiology, covenant, and more.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The sixth commandment (Deut. 5:17) calls for the respect of life, especially underscoring the dignity of human life. It is treated in Deut. 19:1–22:4. For example, while defending human life and condemning murder, this material distinguishes accidental deaths, explains legal protections for those who have killed someone (19:1–10), and encourages proper judicial proceedings (19:11–13). It also sets apart just war as an example of when life may be taken with immunity (20:1–20) and demands execution for capital felons (21:22–23).

The seventh commandment (Deut. 5:18) warns against sexual sins and immoral intermixing of things which should not be mixed together. It covers 22:5–23:14. This commandment is the most difficult to discern in its section. But given the relative clarity of the ten commandments outline in the remainder of the Deut. 6:4–26:15, it would seem to be required. For example, various types of sexual sins include transvestism (22:5), sexual charges against a wife (22:13–20), adultery and fornication (22:22–24), rape (22:25–29), and incest (22:30), each of which threatens the unity of the family and the community. This law is illustratively reinforced by discouraging the mixing of seeds, animals, and clothing fibers (22:9–11)

The eighth commandment (Deut. 5:19) explains why stealing is immoral. It is covered in Deut. 23:15–24:7. This section enforces ownership rights and encourages respecting others. For example, it covers the problem of escaped foreign slaves (23:15–16) and implies that offspring forced into prostitution steals their self-respect (23:17–18). It continues by prohibiting charging interest on poor loans which robs the poor of their ability to escape debt (23:19–20), and robbing God by refusing to pay vows (23:21–23).

The ninth commandment (Deut. 5:20) requires honesty in one’s witness, promoting confidence in the truth. This is briefly covered in Deut. 24:8–16. For example, this section demonstrates the danger of dishonesty in Miriam’s false charge against Moses (24:8–9), warns about a lack of trust in handling pledges (24:10–13), condemns disrespectfully failing to promptly pay workers (24:14–15), and prohibits criminal witness against innocent family members of criminals (24:16).

The tenth commandment (Deut. 5:21) rebukes covetousness, which is a desire for something that belongs to another. Moses applies this matter to situations denying a person’s rights and privileges regarding his own property and life. This material is found in Deut. 24:17–26:15. For example, this section warns that coveting perverts justice for the weakest members by taking all they have as a loan pledge (24:17–18) or denying them access to the overage from one’s crops (24:19–20).

August 19, 2022

AD 70 & THE TEMPLE’S FAILURE (2)

PMW 2022-062 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2022-062 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

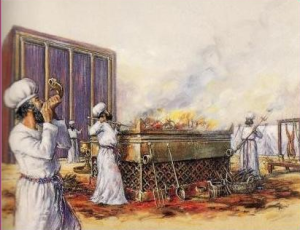

I am completing a brief study on the Jewish temple’s failure through abuse, showing the necessity of its destruction under God’s wrath in AD 70. My previous article should be consulted for context.

Interestingly, on several occasions before Christ’s coming, the temple undergoes cleansings because of profanations by Ahaz (2Ch 29:12ff), Mannaseh (2Ch 34:3ff), Tobiah (New 13:4-19), and Antiochus (1Mac 4:36ff; 2Mac 10:1ff). The temple of Christ’s day is also corrupt, for Christ himself symbolically cleanses it when he opens his ministry (Jo 2:13-17) and as he closes it (Mt 21:12-13) — even though it is under the direct, daily, fully-functioning administration of the high priesthood.

As Richard Horsley (Jesus and the Spiral of Violence, 163) well notes: “Once in Jerusalem, [Jesus] moves directly into the symbolic and material center of the society, the power based of the ruling aristocracy” to challenge it. In fact, Horsley (300) argues, “Jesus attacks the activities in which the exploitation of God’s people by their priestly rulers was most visible.” Thus, “Jesus’s action is a clear condemnation of the priestly authorities, who have permitted these practices: the result is that ‘the chief priests’ join ‘the scribes’ in plotting his death (cf. 3:6)” (Morna Hooker, The Gospel according to Saint Mark, 268).

Christ calls the temple they are controlling a “robbers’ den” (Mt 21:13) only to later have the “chief priests and the elders” demand the release of the robber Barrabas over him (Mt 27:40; Jn 18:40). [1] In fact, they ask him on what authority he drives out the moneychangers and teaches in the temple, since they had not commissioned him to clean up the corruption (Mt 21:23). As Julie Galambush (The Reluctant Parting, 68) observes: “It is no coincidence that Matthew’s extravagant assertions of Jesus’ authority are placed in the context of confrontations with the Pharisees.”

Before Jerusalem Fell

(by Ken Gentry)

Doctoral dissertation defending a pre-AD 70 date for Revelation’s writing. Thoroughly covers internal evidence from Revelation, external evidence from history, and objections to the early date by scholars.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

James DeYoung (Jerusalem in the New Testament, 63) argues that Christ’s actions are not an effort at reform but a testimony against the present cultus. This is evident in that in the first cleansing he alludes to its destruction (Jn 2:19) and in the immediate context of the second he curses the fig tree as symbol of Israel’s corruption (cf. Hos 9:10, 16; Mic 7:1). Ferdinand Hahn (The Titles of Jesus in Christology, 155) agrees: “The procedure of Jesus in the temple precincts can only be understood as a symbolic action proclaiming judgment and punishment on the Jewish sanctuary if it is connected with the cursing of the fig tree, as it is in the present redactional context.”

N. T. Wright (Jesus and the Victory of God, 416) well summarizes the evidence that Christ was symbolically declaring its judgment: “Virtually all the traditions, inside and outside the canonical gospels, which speak of Jesus and the Temple speak of its destruction. Mark’s fig-tree incident; Luke’s picture of Jesus weeping over Jerusalem; John’s saying about destroying and rebuilding; the synoptic traditions of the false witnesses and their accusation, and of the mocking at the foot of the cross; Thomas’ cryptic saying (‘I will destroy this house, and no one will be able to rebuild it’); the charge in Acts that Jesus would destroy the Temple: all these speak clearly enough, not of cleansing or reform, but of destruction.”

The temple authorities, including especially the high priests, were irrevocably corrupt long before the Jewish War. Indeed, the high priest in Jesus’ day was Anna, of whom Raymond Brown (The Gospel according to John, 1:121) notes: “the corruption of the priestly house of Annas was notorious.” According to Josephus: “The principal high-priestly families, with their hired gangs of thugs, not only were feuding among themselves, but had become predatory, seizing by force from the threshing floors the tithes intended for the ordinary priests” (Ant. 20.180, 206-7).

The Babylonian Talmud laments: “Woe is me because of the house of Boethus; woe is me because of their staves! . . . Woe is me because of the house of Ishmael the son of Phabi; woe is me because of their fists! For they are High Priests . . . and their servants beat the people with staves” (Pesah. 57a). “Starting by about 58 or 59, the high priests began surrounding themselves with gangs of ruffians, who would abuse the common priests and general populace” (Horsley, “High Priests and the Politics of Roman Palestine,” 45). In fact, “the high priests and royalists actually contributed to the breakdown of social order through their own aggressive, even violent, predatory actions” (Horsley, 24).

Completely frustrated at the high priests’ continuing collaboration with the Romans, “a group of sages/teachers called Sicarii or ‘Daggermen’ turned to assassinating key high-priestly figures (B.J. 2.254-57). . . . The population of Jerusalem was as dependent on the Temple-high-priesthood system as the high-priestly aristocracy was on their Roman sponsors” (Horsley, Galilee: History, Politics, People, 73-74). In fact, “when the Roman troops under Cestius finally came to retake control of Jerusalem . . . the priestly aristocracy attempted to open the gates to them . . . (November 66; B.J. 2.517-55)” (Horsley, Galilee 74).

Blessed Is He Who Reads: A Primer on the Book of Revelation

By Larry E. Ball

A basic survey of Revelation from the preterist perspective.

It sees John as focusing on the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in AD 70.

For more Christian studies see: www.KennethGentry.com

Jesus preaches against the temple’s degenerate condition when he mentions the death of the son of Berechiah who was “murdered between the temple and the altar” (Mt 23:35). When we last hear Christ publicly referring to the temple he calls it “your house” rather than God’s house (Mt 23:38). Then he declares it “desolate” and ceremoniously departs from it (Mt 23:38-24:1). And it “is extremely significant that the declaration of abandonment (v. 38) is preceded by the seven woes upon the religious hierarchy of Jerusalem (vv. 13-36)” (DeYoung, Jerusalem in the New Testament, 91). The Qumran community existed largely because of their disdain for the corruption of the temple.

During the interchange regarding his temple actions, Jesus refers to John Baptist who calls Israel to repentance (Mt 21:24-25). John calls the people out of Jerusalem into the wilderness to repent, thereby effecting a reverse exodus (Mt 3:1-5) — as if Jerusalem is now Egypt and must be left (cp. Rev 11:8; 18:4). And he turns down the religious leaders, the Pharisees and Sadducees, demanding that they bring forth fruit in keeping with repentance” instead of basking in their pride supposing “that you can say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham for our father’; for I say to you, that God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham” (Mt 3:7-9). Christ even denounces Israel’s religious elite as “an evil and adulterous generation” (Mt 12:38-39).

Furthermore, Jesus intentionally supplants the temple cult ceremonies in his ministry (see Gaston, ch 3). He proclaims that he is “greater than the temple” (Mt 12:6). He teaches that loving God and neighbor “is much more than all burnt offerings and sacrifices” (Mk 12:22). He authoritatively declares the leper cleansed (Mk 1:40-45) instead of directing him to go to the priests in order to secure cleansing (Lev 14:2ff). He touches the unclean woman, but is not made unclean himself (Mk 5:25-34; cp. Lev 5:2-3). He declares that food does not make one unclean (Mk 7:15; cp. Lev 11:4ff). He does not even pay the temple tax except on the occasion when it might cause offense (Mt 17:24-27). And then he does not pay it out of his own purse and by means of a unique miracle. In this context “Jesus’ declaration that ‘the sons are free’ thus appears to have provided an unmistakable declaration of independence from the Temple and the attendant political-economic-religious establishment” (Horsley, Jesus and the Spiral of Violence, 282).

This study will continue in my next article.

Note

1. Eventually the Jews would be overrun by robbers: “As for the affairs of the Jews, they grew worse and worse continually, for the country was again filled with robbers and impostors, who deluded the multitude” (Josephus, Ant. 20:8:5). We should remember that the Gospels are written awhile after Christ and record information to assist Christians in that later time. That Christ denounces the temple as a robber’s den should strike a sympathetic chord with Jewish Christians a few decades later. Josephus notes that the highpriests abuse the people and take away the tithes (Ant. 20:9:2), even making seditious attacks in Jerusalem (Ant. 20:9:4).

Commentary on Matthew 21–25 Notice

I am currently raising funds to engage research and writing on a commentary on Matthew 21–25, which contains the Olivet Discourse. This commentary will provide a Composition Critical approach to this textual unit in Matthew. In doing thus, it will show why Matthew presents Jesus’ Olivet Discourse as he does, in a way that differs in several respects from Mark and Luke. This commentary will demonstrate that the Olivet Discourse deals with both the AD 70 destruction of the temple and the Second Advent (which is anticipated by AD 70). This is important for presenting Christ as more than just a Jewish sage concerned for one nation.

If you would like to support this, please see my GoodBirth Ministries website, where you can give a tax deductible gift and receive a free occasional newsletter updating donors on my research. Thanks for your help! Click: GoodBirth Ministries.

August 16, 2022

AD 70 & THE TEMPLE’S FAILURE (1)

PMW 2022-061 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2022-061 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

AD 70 is an important date in redemptive-history. In that year the ancient temple of Israel was destroyed, never to be rebuilt. This catastrophe is anticipated in the OT. Over and over again the temple cult is disparaged by the OT prophets when Israel falls into sin: Isa 1:10-17; 29:13; 43:23-24; Jer 6:20; 7:1-6, 21-22; 11:15; Eze 20:25; Hos 6:5-6; Am 4:4-5; 5:21-25; 9:1; Mic 6:1-8; Mal 1:10. Jeremiah even presents God as dramatically denying he ever directed Israel to sacrifice: “For I did not speak to your fathers, or command them in the day that I brought them out of the land of Egypt, concerning burnt offerings and sacrifices. But this is what I commanded them, saying, ‘Obey My voice, and I will be your God, and you will be My people; and you will walk in all the way which I command you, that it may be well with you’ “ (Jer 7:22-23).

The problem with the temple cult arises not from the God-ordained ritual, but those who minister the ritual. Consequently, “from at least the time of Malachi there had been protests about the priests, whose corruption meant that the sacrifices offered in the temple were neither pure nor pleasing to the Lord (Mal. 3:3f.). Similar complaints are found in the Psalms of Solomon (2:3-5; 8:11-13), at Qumran (1Qp Hab. 8:8-13; 12:1-10; CD 5:6-8; 6:12-17) and the Talmud (B. Pes. 57a), while Josephus describes the way in which the servants of the priestly aristocracy stole tithes from the ordinary priests (Antiquities XX.8.8; 9:2)” (Morna Hooker, The Gospel according to Saint Mark, 264).

Survey of the Book of Revelation

(DVDs by Ken Gentry)

Twenty-four careful, down-to-earth lectures provide a basic introduction to and survey of the entire Book of Revelation. Professionally produced lectures of 30-35 minutes length.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

In the Gospel record Jesus’ subtle conduct and overt teaching prepare us for the removal of the temple as both theologically unnecessary and as spiritually corrupt. John’s Gospel is especially interesting in this regard: In Jn 1:14 Christ appears as God’s true “tabernacle” (eskēnōsen en ēmin). [1] This theme of Jesus replacing the religious features of Israel recurs repeatedly in his ministry: In 1:51 he, rather than the temple or high priest, is the nexus between heaven and earth because “the angels of God [are] ascending and descending on the Son of Man.” In 2:19-21 he declares his body the true temple. In 4:21-23 he tells the Samaritan woman the physical temple will soon be unnecessary.

When he attends the festival of Tabernacles (Jn 7:2ff), in 7:37-39 he himself becomes the living water which is associated both with the festival reminder of Moses producing water from the rock (Ex 17:1-7; Nu 20:8-13) and the temple promise (Zec 14:8; Eze 47:1-11). In 8:12 he calls himself “the light of the world,” which reflects the festival ceremony (Sukkah 5:1). In the “I am” debate in Jn 8:13-59 “Jesus was appropriating to himself . . . the whole essence of the Temple as being the dwelling-place of the divine Name” (P. W. L. Walker, Jesus and the Holy City, 168).

In Jn 10 Christ comes to the Feast of Dedication in Jerusalem, which celebrates the Maccabean victory in reclaiming the temple and re-consecrating the altar and temple. There Jesus does not enter the temple, but comes only to Solomon’s portico (10:23; cp. Jo 11:56). He declares himself to be the one “whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world” (10:36). In 12:41 while referring to Isa 6:5 Christ becomes the Shekinah glory of the temple. Walker (172-73) argues that the upper room episode (Jn 13-17) reflects a “Temple-experience” beginning with foot-washing as an initiation ritual (Jn 13:3ff) and ending with the “high-priestly prayer” (Jn 17). Thus, it appears “John’s over-riding message is that the Temple has been replaced by Jesus” (Walker, 170).

Keys to the Book of Revelation

(DVDs by Ken Gentry)

Provides the necessary keys for opening Revelation to a deeper and clearer understanding.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

On and on I could go. In fact, in all the Gospels “there was no denial of its previous theological status, but that status was now appropriated by Jesus” (Walker, 164). As Brown (The Gospel of John, 1:122) observes: The Gospel of “John belongs to that branch of NT writing (also Hebrews; Stephen’s sermon in Acts vii 47-48) that was strongly anti-Temple.” He even notes that this may explain why he is called a “Samaritan” in Jn 8:48, in that they reject the Jerusalem temple.

By Jesus’ appropriating the temple’s status, it is rendered unnecessary. But at the same time, its corrupted employment by the Jews required its destruction, not simply the removal of its status, allowing it to remain as an empty shell. And its destruction is a key issue in the NT revelation. In the next few articles I will be considering this matter. Stay tuned!

Notes

1. The writer of Hebrews critiques the temple in terms of the transitory tabernacle. He does this because the old covenant and all of ritual is “becoming obsolete and growing old” and “is ready to disappear” (Heb 8:13). God is about ready to shake “created things, in order that those things which cannot be shaken may remain” (Heb 12:27). The “created things” are the physical implements of the temple (Heb 9:11, 24).

August 12, 2022

REVELATION’S “MANY WATERS” AND JERUSALEM (2)

PMW 2022-060 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2022-060 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

This is the second and final part of a brief series arguing that the “many waters” of Rev. 17:1, 15 refer to Jerusalem’s influence over the diaspora Jews, many of whom were proselyte from the nations.

My second observation regarding the Babylonian-harlot’s sitting on many waters represents Jerusalem’s political influence exercised by means of the diaspora — particularly against Christians —- which is exerted throughout the empire and among the “peoples and multitudes and nations and tongues” (17:15).

Remembering the Jewish danger to Christians (Rev. 2:9; 3:9; cp. Acts 4:3; 5:18; 8:3; 9:2; 12:4; 18:6; 22:4; 24:27; 26:10; Rom 15:31; 2 Cor. 11:24; 1 Thess. 2:14-17; Heb. 10:33-34) and the role of the martyrs in Rev (Rev. 6:9-10; see also: Rev 1:9; 2:9-10; 3:9-10; 11:7-8, 11-13, 18; 12:10; 13:10; 14:11-13; 16:5-6; 17:6; 18:20, 24; 19:2; 20:4, 6), this is a quite significant implication of John’s image. After all, we discover “the common reflection of Jewish opposition in the NT writings” (Rick Van de Water, “Reconsidering the Beast from the Sea (Rev 13.1),” 248).

Survey of the Book of Revelation

(DVDs by Ken Gentry)

Twenty-four careful, down-to-earth lectures provide a basic introduction to and survey of the entire Book of Revelation. Professionally produced lectures of 30-35 minutes length.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

We read in Acts that the Jews “won over the multitudes [ochlous]” against Paul and stoned him (Ac 14:19; cp. 13:45, 50; 14:2). In Ac 17:5 we read that “the Jews, becoming jealous and taking along some wicked men from the market place, formed a mob [ochlopoiēsantes] and set the city in an uproar.” In Thessalonica they were “agitating and stirring up the crowds [ochlous]” (Ac 17:13). “This regularly established link between Jerusalem and the diaspora was of particular importance during the time of organised hostility to the early church. Concerted plans could be made and consistent action followed in many parts at once” (James Parks, The Conflict of the Church and the Synagogue, 11).

By excommunicating Jewish-Christians and resisting them in the public sphere (see Exc 10 at 11:2), the traditional Jews effectively expose Christians to Roman oppression by removing their status as Jews and the protections of religio licita. “The privileges given by the Romans to the Jews . . . were confined to practising Jews, so that by excommunication the Jewish authorities could deprive a Jews of his legal privileges” with the result that “by this simple act of excommunication they could expel a Christian from these privileges and report against him as an atheist” (James Parks, 62, 64).

But it goes even farther, the Jews specifically charge Christians with resistance to Roman rule. In Ac 17:6-7 they drag Christians before the Thessalonican city authorities charging that “they all act contrary to the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, Jesus.” This is similar to their actions in the trial of Jesus where they assert “we have no king but Caesar” in demanding Jesus’ death (Jn 19:15, cf. v 15). Parks (1961: 66) notes that “the Jews of Corinth dragged Paul before the Romans. The charge they brought was that Paul was trying to persuade them to ‘worship God contrary to the Law.’ This is certainly a charge with which they could technically have dealt themselves. . . . The Jews preferred to lay the responsibility on the Romans for deciding what to do.”

The Early Date of Revelation and the End Times: An Amillennial Partial Preterist Perspective

By Robert Hillegonds

This book presents a strong, contemporary case in support of the early dating of Revelation. He builds on Before Jerusalem Fell and brings additional arguments to bear.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Earlier Parks (65) noted that in Acts “Gallio refuses to hear the charge” which shows that for Luke “the Jews were not compelled to bring Paul before the Roman court.” The Jewish community is using the Roman judicial apparatus to stir up trouble for the Christians.

Consequently, I believe a strong and compelling case may be made for the waters of Rev. 17 representing the influence of Jerusalem over her far-flung diaspora.

August 9, 2022

REVELATION’S “MANY WATERS” AND JERUSALEM (1)

PMW 2022-059 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2022-059 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

The “many waters” mentioned in Revelation 17 is often used to counter the Jewish-harlot interpretation of Revelation.

Rev. 17:1 and 15 read:

Then one of the seven angels who had the seven bowls came and spoke with me, saying, “Come here, I will show you the judgment of the great harlot who sits on many waters” (v. 1).

And he said to me, “The waters which you saw where the harlot sits, are peoples and multitudes and nations and tongues” (v. 15).

This is a frequent challenge brought against the Babylon=Jerusalem interpretation. And it certainly offers a reasonable interpretation. In fact, it is a key argument in favor of the identity of the harlot as Rome among standard preterists (as opposed to my Redemptive-historical preterism, which sees the bulk of Revelation as directed against Jerusalem and Israel). Thus, it deserves a response. I will provide a two part response, beginning in this posting and continuing in the next.

[image error]For more information and to order click here.

" data-image-caption="" data-medium-file="https://postmillennialismtoday.files...." data-large-file="https://postmillennialismtoday.files...." class="alignright size-full wp-image-209" src="https://postmillennialismtoday.files...." alt="Navigating the Book of Revelation: Special Studies on Important Issues" />Navigating the Book of Revelation (by Ken Gentry)

Technical studies on key issues in Revelation, including the seven-sealed scroll, the cast out temple, Jewish persecution of Christianity, the Babylonian Harlot, and more.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

In Rev. 17, the angel states of the “the great harlot” that she “sits on many waters (17:1c). How shall the Redemptive-historical Preterist respond? I believe there is abundant evidence that this can easily apply to Jerusalem. Let’s see how this is so.

It is well-known that John is taking up the mantle of an OT prophet. He intentionally mimics their style, even alluding to their words. That is, he uses Greek grammar that intentionally suffers from Hebrew interference (Hebraisms) and he employs over 400 allusions to the OT (the most of any book in the NT). That being the case, it would appear that he is alluding to Jer 51:12–13 which refers to OT Babylon’s complex network of canals on the Euphrates: “Lift up a signal against the walls of Babylon; / Post a strong guard, / Station sentries, / Place men in ambush! / For the LORD has both purposed and performed / What He spoke concerning the inhabitants of Babylon. / O you who dwell by many waters, / Abundant in treasures, / Your end has come, / The measure of your end.”

But John is not being literal here, for at 17:15 he interprets the waters not as canals or rivers but as “peoples and multitudes and nations and tongues.” As already noted, this allusion to the “many waters / peoples” of the great pagan city in the OT leads many quite reasonably to assume he is transferring the image to Rome and her vast empire over many peoples and nations. The fact that she “sits” [kathēmenēs] on these waters speaks of her ruling over them, for elsewhere in Revelation sitting is generally the posture of governance (3:21; 4:2-3; 5:1, 7, 13; 6:16; 7:10, 15; 11:16; 14:15-16; 19:4; 20:4, 11; 21:5). And Revelation’s Babylon does see herself as ruling, for she claims: “I sit [kathēmai] as a queen [basilissa]” (18:7b).

Yet In light of the abundant evidence for Babylon representing Jerusalem in John’s judicial drama against Israel, we should look in another direction for testing these waters, you might say. What is the proper interpretation of her sitting on “many waters” (17:1) representing “peoples [laoi] and multitudes [ochloi] and nations [ethnē] and tongues [glōssai]” (17:15)? These statements signify two significant realities.

Babylon-Jerusalem’s ruling influence is exercised over the vast population of diaspora Jews. If taken in terms of her authority over diaspora Jews derived from many nationalities, Jerusalem eminently qualifies for such a description. This would include its many non-Jewish proselytes, for “in the Graeco-Roman period, there is evidence of many converts to Judaism, as well as of sympathizers, or God-fearers” (Dictionary of Judaism in the Biblical Period, 505).

Blessed Is He Who Reads: A Primer on the Book of Revelation

By Larry E. Ball

A basic survey of Revelation from the preterist perspective.

It sees John as focusing on the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in AD 70.

For more Christian studies see: www.KennethGentry.com

In fact, Louis Feldman (in Shanks, Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, 5) speaks of “the outstanding success of Jewish proselytism.” He notes further that “the vast expansion of Judaism through proselytism may also have made the Romans nervous.”

J. M. G. Barclay (Jews in the Mediterranean Diaspora, 299) mentions that Dio (57:18:5a) “asserts that the expulsion [of Jews from Rome under Tiberius in AD 19] took place because the Jews were converting many Romans to their customs.” Albert Bell (A Guide to the New Testament World, 95) agrees: “throughout the first century or so of the empire the Jews in Rome were numerous and aggressive proselytizers, so aggressive that they were expelled under Tiberius and again under Claudius.” (see: Tac. Ann. 2:85; Hist. 5:5; Suet. Claudius 25).

Josephus states that the Jews “also made proselytes of a great many of the Greeks perpetually” (J.W. 7:3:3 §45). The Mishnah, Talmud, and other rabbinic documents commonly mention the proselytes. Douglas Hare (The Theme of Jewish Persecution of Christians in the Gospel according to St. Matthew, 9) comments: “the eagerness with which proselytes were sought and the success of such efforts are attested by pagan, Jewish and Christian writers of the period.” The ancient Jews saw the diaspora as God’s goodness toward the Gentiles in sowing the Jews among them: “The Holy One, Blessed be He, did righteousness in Israel in that he ‘scattered’ them amongst the nations” (b. Pes. 87b).

We know from abundant literary and archaeological evidence that the diaspora was a powerful minority throughout the empire. Philo (Flacc. 45-46) writes that “no one country can contain the whole Jewish nation, by reason of its populousness; on which account they frequent all the most prosperous and fertile countries of Europe and Asia, whether islands or continents, looking indeed upon the holy city as their metropolis in which is erected the sacred temple of the most high God.” He writes to the emperor Caligula (Embassy 36 §281-284]):

Concerning the holy city I must now say what is necessary. It, as I have already stated, is my native country, and the metropolis, not only of the one country of Judaea, but also of many, by reason of the colonies which it has sent out from time to time into the bordering districts of Egypt, Phoenicia, Syria in general, and especially that part of it which is called Coelo-Syria, and also with those more distant regions of Pamphylia, Cilicia, the greater part of Asia Minor as far as Bithynia, and the furthermost corners of Pontus. and in the same manner into Europe, into Tessaly, and Boeotia, and Macedonia, and Aetolia, and Attica, and Argos, and Corinth and all the most fertile and wealthiest districts of Peloponnesus. And not only the continents full of Jewish colonies, but also all the most celebrated islands are so too; such as Euboea, and Cyprus, and Crete. I say nothing of the countries beyond the Euphrates, for all of them except a very small portion, and Babylon, and all the satrapies around, which have any advantages whatever of soil or climate, have Jews settled in them. So that if my native land is, as it reasonably may be, looked upon as entitled to a share in your favour, it is not one city only that would then be benefited by you, but ten thousand of them in every region of the habitable world, in Europe, in Asia, and in Africa, on the continent, in the islands, on the coasts, and in the inland parts, And it corresponds well to the greatness of your good fortune, that, by conferring benefits on one city, you should also benefit ten thousand others, so that your renown may be celebrated in every part of the habitable world, and many praises of you may be combined with thanksgiving.

When writing of the Jews who come to the temple feasts, Philo speaks of “innumerable companies of men from a countless variety of cities” (Spec. Laws 1:12 (§69-70).

Josephus records Agrippa’s speech attempting to quell the growing revolt against Rome. Agrippa states that “there is not a people in the world [epi tēs oikumenēs] which does not contain a portion of our race” (J.W. 2:16:4 §398; cp. Ap. 2:282). Josephus (J.W. 7:3:3 §43) himself states: “For as the Jewish nation is widely dispersed over all the habitable earth among its inhabitants, so it is very much intermingled with Syria by reason of its neighborhood, and had the greatest multitudes in Antioch by reason of the largeness of the city.” He mentions “a great multitude of Jews who dwelt in their [Ionian] cities” (Ant. 16:2:3 §27–28). Strabo of Cappadocia complains: “Now these Jews are already gotten into all cities; and it is hard to find a place in the habitable earth that hath not admitted this tribe of men, and is not possessed by them” (Ant. 14:7:2 §115) We should not be surprised, since God promises that Abraham will be a “father of many nations [ethnōn]” (Ge 17:5; Ro 4:17-18).

John’s image well fits the NT witness elsewhere, for in Ac 2:5 we read that at Pentecost there are “Jews living in Jerusalem, devout men, from every nation [pantos ethnous] under heaven.” In addition, Luke’s description of their surprise at the phenomenon of tongues highlights the matter: “how is it that we each hear them in our own language to which we were born? Parthians and Medes and Elamites, and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the districts of Libya around Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabs — we hear them in our own tongues [glōssais] speaking of the mighty deeds of God” (Acts 2:8-11). Ac 4:27 speaks of “the peoples [laois] of Israel” who were “gathered together against Thy holy servant Jesus.”

To be continued (if my computer doesn’t crash again!).

August 5, 2022

UNDERSTANDING THE OLIVET DISCOURSE

PMW 2022-058 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

On this site, my most popular postings deal with either the Book of Revelation or the Olivet Discourse. The main focus of my site is obviously the postmillennial hope and its affirmation of the glorious progress of the gospel to victory in history. However, the judgment issues emphasized in both Olivet and Revelation are necessary to understand if one is going to defend gospel victory.

I recently spoke at a conference where I gave five lectures on Matthew’s version of the Olivet Discourse. This was videotaped and is now in available as a DVD set titled “Understanding the Olivet Discourse.” The lectures were well received and the DVDs are doing well, for which I am thankful and encouraged.

The five lectures I presented covered all the major issues in Matthew 24–25, providing a helpful study on this noteworthy teaching by Christ. In the present article I will provide a brief introduction to the lectures, hoping to whet your appetite. This DVD set should be a helpful means for presenting the orthodox preterist view of the Lord’s great discourse. I highly recommend your buying it for that purpose — as does my wife, two of my three children, and two of my six grandchildren (the others were in bed asleep when I asked them if they would recommend viewing the lectures, due to elementary school starting the next day).

The five lectures were:

The Apostle’s Anticipation of the Olivet DiscourseThe Disciples’ Expectation in the Olivet DiscourseThe Christian’s Questions about the Olivet DiscourseThe Lord’s Transition in the Olivet DiscourseThe Final Judgment’s Presentation in the Olivet DiscourseThe Apostle’s Anticipation of the Olivet DiscourseThis opening message provides the necessary introduction to the Apostle Matthew’s version of Olivet, noting that it is unique in being Jesus’ only fully eschatological discourse. It also points out that it is the fullest of the three versions found in the Synoptic Gospels, covering two full chapters (Matt. 24–25). This should provide us with incentive to carefully study it for a fuller understanding of Olivet.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Understanding the Olivet Discourse (DVD set) by Ken Gentry

This five-lecture set presents all the essential elements necessary for properly understanding the Olivet Discourse. It shows that the Discourse opens with prophecies regarding the AD 70 destruction of the temple, but then concludes with the Final Judgment to which AD 70 points.

For more educational materials see: www.KennethGentry.com

_____________________________________________________________________________

Thus, to better understand the Discourse, I highlight its setting in Matthew. I point out that the Apostle develops the growing Jewish antipathy to Jesus and the developing Gentile reception of him. It opens with the Jews fearful upon hearing of Christ’s birth (Matt. 24:3), while the Gentiles come to see him (Matt. 2:1–2). It closes with Jesus ending his special focus on Israel (cf. 10:5–6; 15:24), while opening his mission to “all nations” (Matt. 28:19–20). Thus, as Jesus’ final major Discourse of five in Matthew, Olivet becomes the capstone to Jewish resistance and Gentile acceptance. Matthew’s well-crafted Gospel builds toward Olivet in a impressive, instructive, and important way.

The Disciples’ Expectation in the Olivet DiscourseTurning from the Apostle Matthew’s anticipating Olivet in the structuring of his Gospel, I then proceeded to highlight how the Disciples received this surprising Discourse. In this lecture I strongly emphasize the exegetical evidence that the great tribulation is past, having occurred in the events leading up to and including AD 70. This affirmation oftentimes spins people’s toupees around when they first hear it. But the conferees knew what I was going to be presenting. So they took it well, with very few of them crying out: “Heretic! What have we got to look forward to if the great tribulation judgment is over!” Or: “Away with him! We have no interpreter but Lindsey!” Nor did they burst out in song, singing: “My hope is built on nothing less that Scofield’s notes and Moody Press.”

My first point in this message was to stress that the tribulation was historically limited, i.e., to the first century. That is, it was limited to “this generation” to which Jesus spoke (Matt. 24:34). Thus, it was extremely relevant to his original audience, which lived in a dramatically important period of redemptive-history.

Furthermore, the tribulation was focused on the area around Jerusalem and Judea (Matt. 24:16). It was not a worldwide judgment, though AD 70 was a harbinger of that ultimate judgment, the Final Judgment at the end of history. Like the several Old Testament “day of the Lord” events, it was important in itself, but ultimately pointed beyond itself to a fuller reality.

The Christian’s Questions about the Olivet DiscourseIn this message I focused on the modern Christians’ confusion regarding the historical fulfillment of the Discourse. I survey the leading verses that confound them, explaining them in terms of both the local context in Matthew, as well as the broader context of all of Scripture.

Olivet Discourse Made Easy (by Ken Gentry)

Verse-by-verse analysis of Christ’s teaching on Jerusalem’s destruction in Matt 24. Shows the great tribulation is past, having occurred in AD 70, and is distinct from the Second Advent at the end of history.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Oftentimes modern believers cannot initially accept the fact that the great tribulation was the worst ever (Matt. 24:21). They cannot do so because they do not understand what Jesus’ prophetic parlance and the enormity of the destruction of the temple. Nor can they understand “the abomination of desolation” in the broader setting of Scripture (v. 15).

Furthermore, they see Matthew 24:27 as devastating impediment to the past-tense fulfillment of Olivet. For they do not properly understand the structure and flow of the Discourse. This confuses them regarding this reference to Christ’s coming “as lightning.” This coming is a warning that when Christ returns again at the end of history it will be a very clear and dramatic event. Whereas in the first century great tribulation people would be spreading rumors that he is hiding in a room or in the wilderness (vv. 23, 26). Thus, Jesus mentions the nature of his Second Coming to warn that it will not be something that could be hidden.

Other issues tripping up the contemporary Christian include his coming on the clouds (Matt. 24:29), his gathering his elect (v. 31), and so forth. These can all be easily explained in terms of his first-century judgment of Jerusalem. If you don’t believe me, buy the DVD set and you will see. And I recommend you buying two copies of the DVD set just to see if I am consistent (if this marketing ploy works I will be well set, able to engage in

Other issues tripping up the contemporary Christian include his coming on the clouds (Matt. 24:29), his gathering his elect (v. 31), and so forth. These can all be easily explained in terms of his first-century judgment of Jerusalem. If you don’t believe me, buy the DVD set and you will see. And I recommend you buying two copies of the DVD set just to see if I am consistent (if this marketing ploy works I will be well set, able to engage in “a little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to rest”).

The Lord’s Transition in the Olivet DiscourseIn my fourth study I focused on the hotly debated issue of the transition in the Discourse from the first century events to the last century events. That is, the shifting from the AD 70 metaphorical judgment-coming of Christ to the last century literal judgment-coming of Christ to which AD 70 points.

I began this message by carefully analyzing the Disciples’ confused questions in Matthew 24:2. I show how these two questions fuse together in their minds the destruction of the temple with the Second Coming / Final Judgment. This will require that the Lord break them apart. They deemed Christ’s denunciation of the temple (v. 1) as inscrutable without the Second Coming. But in his Discourse he will unscrew the inscrutable.

I show how the Disciples’ are frequently confused at Jesus’ teaching, requiring him to straighten them out. And that is what he does in the way he treats their two questions sparking the Discourse. He warns that some will mislead them (Matt. 24:4), but that they should not allow themselves to be misled — by properly understanding what he will teach them.

The Lord draws a distinction between the first century temple judgment and the last century final judgment, beginning in Matthew 24:34–36. After this transition passage (properly understood) he will then deal with the Second Coming as a distinct and distant future event whose time is unknowable, even to Jesus himself (v. 36). Whereas the coming of the temple’s destruction was known to be in their lifetimes (v. 34). I provide thirteen reasons that there must be a transition from the first century judgment on the temple to the last century judgment on the world. Jesus is not simply a Jewish sage concerned only with Israel; rather he is the Lord of all nations, who themselves must be judged as well.

The Final Judgment’s Presentation in the Olivet DiscourseHaving demonstrated that Jesus distinguishes two events in the Disciples’ double-question and that he establishes a transition in the midst of his Discourse, I then proceeded to explain Matthew 24:37–25:46. As I surveyed these verses I showed how they fundamentally differ from the preceding verses dealing with AD 70. I also set the teaching in this section in the larger scope of Christ’s relation to the nations.

Conclusion

I am working on a major commentary on Matthew 21–25, whereby I hope to more fully explain the Olivet Discourse from an orthodox preterist perspective. But the two chapters containing the actual Discourse are fundamental to understanding Jesus’ eschatology. I hope you will review these lectures and learn how to defend the preterist viewpoint without slipping into the hyperpreterist nuisance and while extricating yourself from the dispensational nonsense.

August 2, 2022

REVELATION’S PARAENETIC IRRELEVANCE?

PMW 2022-058 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

Many opponents of the preterist analysis complain that it removes any practical usefulness and continuing relevance of Revelation today. This is a rather common complaint. It arises from the evangelical conviction that “all Scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16). Thus, if it renders Revelation irrelevant, it must not be a proper hermeneutic approach.

Theologians’ Concerns

F. J. Murphy expresses the general concern among many: “an abiding problem is what relevance Revelation has to today’s world.” Abraham Kuyper complains that preterism “renders the book of Revelation meaningless to us, as it makes its vision to hark back to events that transpired in the early centuries of the Christian church.” Craig Koester applies this issue particularly to preterism when he suggests that “the problem with historical interpretation is that while it restrains certain excesses it can also distance readers from the text in a way that deprives the text of its power.”

Arthur W. Wainwright rejects Wettstein’s preterism, noting that “he neglected the message’s relevance for later generations.” Then he writes off other preterists, seeing it as a “danger” that “their chief interest has been to understand the Apocalypse in terms of the early church’s situation, not to demonstrate its relevance for the modern world.” Wilfrid Harrington agrees with this concern: “While the view makes the work meaningful to its original readers, it renders it basically meaningless for all subsequent readers.” Simon Kistemaker complains: “for believers in subsequent eras, this message has only secondary importance.”

John F. Walvoord concurs: “The preterist view, in general, tends to destroy any future significance of the book, which becomes a literary curiosity with little prophetic meaning.” Donald B. Guthrie complains that “surer exegesis will want rather to draw out the permanent spiritual values against the historical background. . . . It enunciates principles which are always applicable.” It appears that this objection would prefer to listen to John’s sermons to the world rather than read his Revelation to his beleaguered audience.

____________________________________________________

Book of Revelation Made Easy

(by Ken Gentry)

Helpful introduction to Revelation presenting keys for interpreting. Also provides studies of basic issues in Revelation’s story-line.|

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

____________________________________________________

Preterist Response

Though quite widespread, this is the weakest of the objections to preterism. Note the following responses.

First, such complaints are actually declaring an approach we should reject outright, for the argument reduces to the following: “We must reject Revelation’s original meaning for the seven first-century churches in Asia Minor if we cannot discern any practical use of it today.” What if John really did mean to focus on his own contemporary circumstances? For the people to whom he actually writes? Who are suffering for the faith? What if he did really mean to inform them that the events “must shortly take place” (1:1) because “the time is near” (1:3)? Who are we to discount his original meaning so that we may import our own — because it is more relevant to us? I agree with C. K. Barrett — though he is speaking in another context: He warns of the “danger of the unforgivable exegetical sin, the sin of attempting to make a passage mean something other than the meaning intended by the author and conveyed by the words.”

Second, biblical scholarship recognizes that much of the NT is “occasional” literature. That is, most of the epistles are written to deal with specific issues arising in the first-century church, and often in particular local communities. Though Kistemaker complains that preterism reduces Revelation to only “secondary importance” for us today, he himself admits in his very next paragraph that “Paul wrote his epistles to specific churches and individuals, but the message of these letters is as relevant to the worldwide church today as it was to Christians in the middle of the first century.”

A good example of this is found in 1 Corinthians. It is particularly significant in this regard in that Paul deals with one specific issue after another that is presented to him by the Corinthians regarding their own unique struggles and controversies (e.g., 1Co 7:1, 25; 8:1; 12:1; 16:1). Consider the case of a particular individual involved in a sinful relationship with his father’s wife: “It is actually reported that there is immorality among you, and immorality of such a kind as does not exist even among the Gentiles, that someone has his father’s wife” (1Co 5:1). Yet we may draw from this very narrow, historical situation practical principles for our own use today. And we certainly should not dismiss Paul’s letter because it does not deal directly with our own situation today.

Stephen Smalley well notes of Revelation that “the storyline can be deconstructed , and the audience can become any listeners at any time. For the writer’s message has a spiritual and doctrinal and practical dimension, which is ultimately universal and eternal in significance.” Specifically, in Revelation we learn of God’s judgment upon his OT people for breaking covenant with him (thereby demonstrating the importance of covenant-keeping), see Christ defending his persecuted saints who valiantly endure for the faith (thereby encouraging confidence in other trying situations), learn of the conclusion of the old covenant economy and the universalization of the true faith (thereby discouraging a return to Judaic worship-forms), hear his explaining the loss of Jerusalem and the temple (though both of these long figure prominently in redemptive history), discover the ultimate source of evil in the world (Satan), and more.

_______________________________________________

Blessed Is He Who Reads: A Primer on the Book of Revelation

By Larry E. Ball

A basic survey of Revelation from the preterist perspective. It sees John as focusing on the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in AD 70.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

______________________________________________

Revelation is vitally important to the first-century church in showing that her first trials will not be her last. She must know that if she can in her infancy endure the most grievous trials from her religious mother (Israel) and her political rulers (Rome), she can endure anything as she grows to maturity. Preterist Moses Stuart comments regarding God’s first-century judgments: “This overthrow was an earnest of the fate of all future persecutions.” Therefore, it holds forth a future glory for God’s people that will issue out of her earlier sufferings.

Continuing in Stuart, he puts the matter well when he explains: “I do not think it was the definite purpose of the Apocalyptist that his book should be considered, in respect to its general tenor and meaning, as limited merely and only to the objects or occurrences which called it forth. The maxim: Ex uno disce omnia [‘from one learn all things’], is one which I should, in a qualified way, apply here with unhesitating confidence. The same Saviour, who has done so much for his church, and promised so much to it in ancient times, will not surely forsake it in later ones. . . . The gates of hell will not — cannot — prevail against the church.”

In his first volume Stuart deals with this question at great length (1: 475–84), noting that the fundamental principle Revelation so dramatically demonstrates is that recurring claim recorded by NT writers and drawn from the OT: “He has put all things in subjection under His feet” (1Co 15:27; cp. Mt 22:44; Mk 12:36; Lk 20:42–43; Ac 2:35; 1Co 15:25; Eph 1:22; Heb 1:13; 2:8; 10:13; cp. Ps 8:6). After all, John declares twice that Christ is “King of kings, and Lord of lords” (Revelation 19:16; cp. 17:14). Stuart well captures the essence of the matter (1:477): “If we should say now that all which respects the destruction of the Jewish persecuting power can no longer be a matter of any interest to us; what is this but to say, that from the past we can gather no lessons of importance in respect to the future; of that we can discover no ground of encouragement, by the fact that God has fulfilled one prediction, that he will fulfill another?”

So then, though Revelation is directed to first-century churches regarding their dire circumstances, we may draw out applications for our own use today (Paul Rainbow). What Lord Bolingbroke notes about history in general, we may apply to Revelation in particular: “History is philosophy teaching by example and also by warning.” And such is Revelation. Indeed, biblical texts have a concrete relevance for their own day even though they are “paradigmatic for God’s purpose” (Paul B. Decock) in later circumstances.

Thus, when we see what Christ promises for the first Christians we may rest assured he will do so for us in our difficult situations. We should understand that Christ absorbs the full brunt of Satan’s fury and emerges triumphant (5:6, 12) — for the good of his church. Though he experiences cruel death as a slain Lamb, he overcomes death to stand forevermore so that he may dwell among (1:13, 18, 20; 14:1; 19:9), defend (5:6; 15:2–4; 17:14), vindicate (6:16; 14:10), and bless (7:17; 19:7) his people. Thus, we should recognize that our temporal decisions have eternal implications and that faithfulness will be rewarded with a blessed future.

Third, if we were to take seriously such complaints, what would become of such OT books as Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, for instance? They focus specifically on Israel’s peculiar history and distinctive covenant involving the tabernacle system. As Stuart puts it: “there are some parts of the Scriptures, which, in one sense, have ceased to be specifically useful to the church, as now existing under the Christian dispensation. We might select, for example, the architectural directions for building the tabernacle, and the history of its construction in accordance with them, as contained in the book of Exodus.”

In dealing with levitical laws, Origen (hom. 7:1 in Num) asks: “What need is there to read these things in the churches?” Yet, they are a part of Scripture. How shall we understand Ps 18 which was written by David regarding his deliverance from the hand of Saul? And Isa 13–14 which prophesies judgment on OT Babylon? Shall we reduce these to “secondary importance” for us today? And if so, what shall we do with these and other such works? Deny their original meaning so that we might re-interpret them in a way more conducive to practical use today? Surely not. After all, Paul powerfully declares that “all Scripture is given by inspiration of God and is profitable” (2Ti 3:16) — even the directions for building the tabernacle.

Fourth, though Walvoord and other futurists make this charge, dispensationalism is guilty of the same problem but from the opposite end of the spectrum. For instance, John Phillips states that “the book of Revelation is occupied for the most part with events that have little bearing on our lives — most of the events will take place after the church has been removed from the scene.” This is because, as Robert Thomas puts it, futurism “views the book as focusing on the last period(s) of world history.” This is significant in that “the rapture of the church comes at a time just prior to the events about to be related” (Thomas), thus, “the prophecies will describe what will happen after the period of the churches has run its course.”

Walvoord notes that “the book, therefore, has a special relevance for the generation which will be living on earth at that time.” Koester complains about populist expositors such as Hal Lindsey and Tim LaHaye, noting: “Historical interpreters reject such speculations, rightly pointing out that the book of Revelation, like the letters of Paul, was written to address the needs of the first-century readers, not to issue predictions that would be unintelligible until the end of time.”

July 29, 2022

A NEW HYPERPRETERISM REBUTTAL

PMW 2022-057 Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

Though Hyperpreterism (a.k.a. Full Preterism) remains a small movement, it also remains a tenacious and noisy one. While Hyperpreterists believe they are giving sound advice regarding biblical interpretation and scriptural eschatology, they provide 99% sound and only 1% advice.

Yet Hyperpreterism does exist and it is present in some evangelical communities and local churches. Therefore, it is deserving of evangelical critiques. And Steve Gregg has provided a helpful, large-scale critique and rebuttal of this eschatological error, titled: Why Not Full-Preterism? A Partial-Preterist Response to a Novel Theological Innovation. Gregg is the host of the national Christian talk show, The Narrow Path. He is also the author of the invaluable book Revelation: Four Views: A Parallel Commentary (1997; rev. 2013).

Why Not Full-Preterism? presents a 370-page analysis of and rebuttal to Hyperpreterism. In his fifteen chapters, the interested evangelical can find a thorough and insightful study of the theological system and its historical development. Though Gregg is an amillennialist (p. xix), as a postmillennialist I find his work even-handed and valuable.

Early on his book, Gregg presents an important notice: “I am not writing so much to attack as to defend the long-settled Christian understanding of the coming of Christ” (p. xx). As I and other orthodox preterists note, Hyperpreterism is not simply an error on a few debatable points of eschatology. Rather it is a wholesale re-structuring of some of the most fundamental aspects of the Christian faith. And one of the key issues that it rejects is the historic doctrine of the future physical resurrection of the dead at the end of history.

The apostle Paul warns about the rejection of the doctrine of the physical resurrection in his lengthy affirmation of physical resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15. There we read in part (vv. 12–26):

“Now if Christ is preached, that He has been raised from the dead, how do some among you say that there is no resurrection of the dead? But if there is no resurrection of the dead, not even Christ has been raised; and if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is vain, your faith also is vain. Moreover we are even found to be false witnesses of God, because we testified against God that He raised Christ, whom He did not raise, if in fact the dead are not raised. For if the dead are not raised, not even Christ has been raised; and if Christ has not been raised, your faith is worthless; you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If we have hoped in Christ in this life only, we are of all men most to be pitied.

“But now Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who are asleep. For since by a man came death, by a man also came the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ all will be made alive. But each in his own order: Christ the first fruits, after that those who are Christ’s at His coming, then comes the end, when He hands over the kingdom to the God and Father, when He has abolished all rule and all authority and power. For He must reign until He has put all His enemies under His feet. The last enemy that will be abolished is death.”

Thus, in Why Not Full-Preterism? Gregg provides a special focus on this Achilles’ heel of Hyperpreterism. Notice these four chapter titles:

7. The Resurrection According to Scripture and History

8. The Resurrection & Rapture According to Full-Preterism

9. Key Disputed Passages on the Resurrection

10. No Marriage in the Resurrection

Gregg notes how the resurrection is even a problem causing disunity in the hyper-preterist movement itself. On p. 19 he writes: “Their conflicting positions concern fundamental matters in the movement. Did such a physical resurrection and rapture of the Church, as most Christians still anticipate, occur (though apparently unnoticed and unrecorded) in A.D. 70, as one camp (e.g., J. Stuart Russell, Milton Terry, Edward E. Stevens) claims? Or were the Resurrection and Rapture invisible, spiritual phenomena by which the Church became glorious and inherited all of her spiritual privileges (equally unnoticed and unrecorded), as others (e.g., Max King, Don K. Preston) insist? Or is the Resurrection the personal experience of every Christian, receiving a new, body [sic] in heaven at the moment of death, while the old one remains buried on earth (apparently held by most full-preterists.”

He notes also that “full-preterists can’t seem to make up their minds as to whether the Resurrection should be viewed as a one-time event, in A.D. 70, or as a process continuing forever as each individual experiences his or her own death” (p. 24).

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Why Not Full-Preterism? A Partial-Preterist Response to a Novel Theological Innovation

By Steve Gregg

A powerful, lengthy analysis of and rebuttal to Hyper-preterism.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

As Gregg engages in their strange arguments, he well notes: “from my reading of full-preterist authors (and debating some of them), I have gained the impression that the most necessary tool in their hermeneutical kit is a shoehorn” (p. 26). Elsewhere, the shoehorn has certainly been useful in the way Jehovah’s Witnesses deal with verses on the deity of Christ. The cover to Gregg’s book is quite appropriate: it shows square pegs breaking as they are being driven into round holes.

Though I have only engaged in presenting some observations from its earliest pages, I hope these will whet your appetite to get a copy of the book. It also offers two chapters on the Olivet Discourse (chs. 13-14). It is one of the better critiques of this aberrant theology that I have seen. I am thankful for Gregg’s labor in this important work. Though I do not agree with all of his observations, I do highly recommend it as a valuable resource.

July 19, 2022

APOSTOLIC SUFFERING

PMW 2022-056 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2022-056 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

In my last blog article I introduced the question: “Is the church called to suffer?” The suffering church motif is widespread in evangelical theology. And one reason it is so is because the church is suffering and has long suffered. Another reason though is that there are numerous verses in the New Testament that seem to confirm this perception.

In the opening article I cited several well-known theologians who make this argument. How can the postmillennialist respond? I am dealing with this question in several articles because of its significance — and because of confusion regarding postmillennialism itself.

In this article I will point out that we must remember that Scripture is occasional and historical. But what does this mean? And how does it help our reply?

Faith of Our Fathers

(DVDs by Ken Gentry)

Explains the point of creeds for those not familiar with their rationale.

Also defends their biblical warrant and practical usefulness.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The New Testament epistles are speaking to real people in their original settings. Historically, the early church to whom the apostles write exists in the throes of a rapidly expanding and increasingly deepening persecution. Consequently, warnings of persecutional suf-fering apply to the original recipients in a direct, relevant, and important way. We misconstrue them if we universalize them so as to require the continued persecution of the church until the second advent. Of course, on those occasions in which God leads us today through similar circumstances, the New Testament directives, principles, and examples certainly apply. Let us specifically consider Gaffin’s main texts.

2 Corinthians 4:7–8

This passage reads: “We have this treasure in earthen vessels, that the excellence of the power may be of God and not of us. We are hard pressed on every side, yet not crushed; we are per-plexed, but not in despair.”

Gaffin comments that Paul “effectively distances himself from the (postmil-like) view that the (eschatological) life of (the risen and ascended) Jesus embodies a power/victory principle that progressively ameliorates and reduces the suffering of the church.” He then informs us that “Paul intends to say, as long as believers are in ‘the mortal body,’ ‘the life of Jesus’ manifests itself as ‘the dying of Jesus’; the latter describes the existence mode of the former. Until the resurrection of the body at his return Christ’s resurrection-life finds expression in the church’s sufferings. . . ; the locus of Christ’s ascension-power is the suffering church” (Gaffin, “Theonomy and Eschatology,” 212).

Gaffin is overlooking the context. Most exegetes note that Paul is here giving an historical testimony of his own apostolic predicament; he is not setting forth a universally valid truth or a prophetically determined expectation. [1] Consider the passage’s wider context. A major point in this portion of Paul’s letter is to defend his apostleship against false apostles (2Co 2:14–7:1). Notice the shift between the apostolic “we” and the recipient “you” (2Co 4:5, 12, 14–15) (F. F. Bruce, 1 and 2 Corinthians, 194; P. E. Hughes, The Second Epistle to the Corinthians, 135).

Gaffin himself admits that “strictly speaking, [Paul’s statements] are autobiographical” (Gaffin, “Theonomy and Eschatology,” 211). That is my point: these statements are personal observations not prophetic expectations.

Furthermore, Gaffin’s comments are far too sweeping: “Over the interadvental period in its entirety, from beginning to end, a fundamental aspect of the church’s existence is (to be) ‘suffering with Christ’; nothing, the New Testament teaches, is more basic to its identity than that.” Is suffering (persecution?) throughout the “entirety” of the interadvental period a “fundamental” aspect of the church’s existence? [2] Is there absolutely “nothing . . . more basic” in the New Testament? If we are not suffering (persecution?), are we a true church? Is Gaffin suffering greatly?

Matthew 24 Debate: Past or Future?

(DVD by Ken Gentry and Thomas Ice)

Two hour public debate between on the Olivet Discourse.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Strimple makes similar observations: “When the apostle Paul thinks of this present time, he thinks of suffering as its characteristic mark (Ro 8:18, see also Jn 16:33; Ac 14:22; Ro 8:36; 2Co 1:5–10; Php 1:29; 3:10; 1 Peter 4:12–19).” In fact, Christ himself “tells his disciples that in this present age they cannot expect anything other than oppression and persecution and must forsake all things for his sake” (Strimple in Bock, Three Views on the Millennium, 63). Surely these overstate the case.

But this is not all of our response. Stay tuned! I will continue this response in the next article.

NOTES

1. For example, see the commentaries on 2 Corinthians by Philip E. Hughes, F. F. Bruce, A. T. Robertson, John Calvin, Marvin R. Vincent, Albert Barnes, E. H. Plumtree, James L. Price, and F. W. Farrar.

2. If persecutional suffering is not in Gaffin’s mind here, then all other forms of suffering are irrelevant to the argument against postmillennialism.

Kenneth L. Gentry Jr.'s Blog

- Kenneth L. Gentry Jr.'s profile

- 85 followers