Kenneth L. Gentry Jr.'s Blog

September 19, 2025

WHY DID JOHN MEASURE THE TEMPLE?

PMW 2025-074 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

The measuring of the temple in Rev. 11:1–2 is an important episode in Revelation. Here we clearly see Revelation’s focus on Israel: this “holy city” with a “temple” must be Jerusalem (Neh. 11:1; Isa. 48:2; 52:1; 64:10; Matt. 4:5; 27:53). In verse 8 John unmasks this “holy city” for what she becomes: an Egypt, a Sodom, the slayer of Christ: “Their bodies will lie in the street of the great city, which is figuratively called Sodom and Egypt, where also their Lord wa s crucified.” Indeed, second century Christians call Jews “Christ-killers” and “murderers of the Lord” (e.g., Ignatius, Magnesians 11; Justin Martyr, First Apology 35; Irenaeus, i 3:12:2)

s crucified.” Indeed, second century Christians call Jews “Christ-killers” and “murderers of the Lord” (e.g., Ignatius, Magnesians 11; Justin Martyr, First Apology 35; Irenaeus, i 3:12:2)

Significantly this passage strongly reflects Jesus’s prophecy in the Olivet Discourse (compare the italicized words):

Luke 21:24b: “Jerusalem will be trampled on by the Gentiles until the times of the Gentiles are fulfilled.”

Revelation 11:2: “But exclude the outer court; do not measure it, because it has been given to the Gentiles. They will trample on the holy city for 42 months.”

These twin passages inform us that the “holy city/Jerusalem” will be “trampled” by the “gentiles” until the “times of the gentiles are fulfilled,” i.e., after “forty-two months.”

Blessed Is He Who Reads: A Primer on the Book of Revelation

By Larry E. Ball

A basic survey of Revelation from the preterist perspective.

It sees John as focusing on the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in AD 70.

For more Christian studies see: www.KennethGentry.com

Evidently Revelation 11:1-2 prophesies the impending destruction of the temple in A.D. 70, for its source Luke 21:24 (and its parallels in Matt. 24 and Mark 13) prophesies that very event. Note the context: (1) Jesus particularly speaks of the first century temple (Luke 21:5-7; cp. Matt. 23:38—24:3; Mark 13:1-4) and (2) he ties his prophecy to his own generation (Luke 21:32; cp. Matt. 24:34; Mark 13:30). And again, the events of Revelation are “soon” (Rev. 1:1) and “near” (Rev. 1:3).

What of “the times of the gentiles”? Daniel 2 prophesies that four successive gentile empires (Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, Rome) will dominate God’s people: they are able to do so because they can strike at the material temple in the specifically defined land. Now after one final period of rage the gentiles will no longer be able to trample God’s kingdom, for it becomes universal and disassociated from a central temple (Eph. 2:19-21), localized city (Gal. 4:25-26), circumscribed land (Matt. 28:19; Acts 1:8), and distinguishable race (Gal. 3:9, 29). As Jesus puts it: “A time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem,” but everywhere (John 4:21).

The trampling of the temple in A.D. 70 (Dan. 9:26-27) after its “abomination” (Dan. 9:27; Matt. 24:15-16; Luke 21:20-21) ends the gentiles’s ability to stamp out the worship of God. In Daniel 9:24-27, Matthew 23:38—24:2, and Revelation 11:1-2 the “holy city” and its temple end in destruction.

The Early Date of Revelation and the End Times: An Amillennial Partial Preterist Perspective

By Robert Hillegonds

This book presents a strong, contemporary case in support of the early dating of Revelation. He builds on Before Jerusalem Fell and brings additional arguments to bear.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

But how do the “times of the gentiles” relate to the forty-two months (Rev. 11:2)? In late A.D. 66 Israel revolts against her oppressive Roman procurator Gessius Florus. By November the Roman governor of the Syrian province, Cestius Gallus, attempts to put down the uprising, but withdraws prematurely for reasons that are unclear (Josephus, Wars 2:17-22; Tacitus, Histories 5:10). A few months later Vespasian is “sent to Judea by Nero early in 67 to put down the revolt.” By August of A.D. 70 the Romans breach the inner wall of Jerusalem, transforming the temple and city into a raging inferno. From Spring of A.D. 67 to August of A.D. 70, the time of formal imperial engagement against Jerusalem, is a period right at forty-two months.

John “measures” for protection (Ezek. 22:26; Zech. 2:1-5) the inner temple (Gk., naos), altar, and worshipers (Rev. 11:1); the “outer court” is “cast out” for destruction (Rev. 11:2). The imagery here involves the protecting of the essence of the temple, its heart (appearing as the worshiping of God by his faithful people), while the externalities of the temple (the husk, the actual material property itself) perish. This mix of physical and spiritual is rooted in the very idea of the temple. For instance, in Hebrews 8:5a we read of an earthly “sanctuary that is a copy and shadow of what is in heaven.” The earthly, external is a copy/shadow of the heavenly spiritual reality. The “man-made sanctuary” is a “copy of the true one” (Heb. 9:24). In Revelation 11 God removes the shadow-copy so that the essential-real remains, which John here portrays as the worshipers in the heart of the temple.

This is much like Paul’s imagery in Galatians 4:22-26 where he contrasts “Jerusalem below” (literal, historical Jerusalem) with the “Jerusalem above” (the heavenly city of God). Or like the writer of Hebrews comparing historical Mt. Sinai that can be touched (Heb. 12:18-21) with spiritual Mt. Zion, the home of “the spirits of men” that “cannot be shaken” (Heb. 12:22-27). This mixture of literal and figurative should not alarm us, for all interpreters find such necessary from time to time. Literalist Robert Thomas, for instance, understands Revelation 19 to teach the return of Christ on a literal horse while urging that his sword and the rod are figurative (Thomas, Revelation 8-22, 387-389). And everyone sees a mixing of physical eating and spiritual eating in John 6:49-50 and physical resurrection and spiritual resurrection in John 5:25-29.

September 16, 2025

666 AS A HEBREW MISSPELLING?

PMW 2025-073 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

In this reply to preterist opponents, I will answer the question:

What about the defective spelling of Nero’s name necessary for the value 666? To get the proper value of 666 out of the name Nero Caesar requires an unusual spelling of his name.

This problem is not insuperable, for we do find this spelling in Aramaic documents from Nero’s reign. Who is to say John could not use a defective spelling, especially one which we actually find from that time period? This spelling would be especially important for his narrative in that this would allow him to match the number for the beast with the name “Nero Caesar” — as he intends (13:17).

Before Jerusalem Fell Lecture (DVD by Ken Gentry)

A summary of the evidence for Revelation’s early date.

Helpful, succinct introduction to Revelation’s pre-AD 70 composition.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Interestingly, elsewhere in Rev John employs an unusual listing of the twelve tribes in 7:4–8. Shall we reject the obvious point that he is there referring to the Israel’s famous tribes?

Furthermore, this complaint will not hold for a time in which spelling is not standardized. For instance, archaeologists have found deeds of sales with names shifting spelling within one short contract. Alon notes “in a deed of sale written in Hebrew … the name of the woman is written twice as Shalom — shlwm (11.6 and 25), and once without the was as shlm, but it is to be pronounced Shalom rather than Shlam; the same is true of a house sale in Hebrew (P. Se’elim 8a) where the wife’s name is spelled once as shlm (1.12) and once as shlwm (1:14). Thus the spelling shlm may not after all express an Aramaic rendering of the Hebrew name shlwm, but the Hebrew name written in defective spelling.”

We see spelling variations in Scripture itself. Scholars debate the spellings of the names of some of the prophets. For instance, in the case of “Elijah,” in the textual history of the NT it is sometimes spelled ēleias (“Elijah”) and sometimes ēlias (“Eliah”) (TDNT 2:929 n 1).

In fact, we also have the famous situation where the city of “Jerusalem” has two distinct spellings in the NT: Ierosalēm (Mt 23:37; Gal 1:17; Heb 12:22) and Ierosoluma (Mt 21:10; Mk 1:5) (BAGD 470). Significantly, “the books belonging to the Hebrew canon [LXX] use the Hebraizing form Ierousalēm, which is not used in secular Greek,” thus Ierousalēm “often had an archaizing or festive ring” (EDNT 2:177). John uses the Hebraic, archaic form Ierosalēm exclusively in Rev (3:12; 21:2, 10), whereas in his Gospel he exclusively employs Ierosoluma (e.g., Jn 5:1; 11:55; 12:12).

Thus, we can see that John’s use of a minority spelling for Nero Caesar does not undermine the Nero interpretation.

Note

1. Gedeliah Alon, “A Cancelled Marriage Contract from the Judaean Desert” JRS 84 (1994): 64-86.

Keys to the Book of Revelation (DVDs by Ken Gentry)

Provides the necessary keys for opening Revelation to a deeper and clearer understanding.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

September 12, 2025

THE JUDGMENT STRUCTURE OF REVELATION

PMW 2025-072 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMW 2025-072 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

With the publisher’s notice that my commentary on Revelation due out this coming Summer, my thoughts return to John’s glorious drama. And with my current research for a commentary on Matthew 21–25, which will involve this passage’s structure and flow, my interest in outlining biblical narratives is re-kindled.

The Determination of Revelation’s Outline

Unfortunately, Revelation is an extremely difficult book to outline. As we might expect from both its cascading judgment visions and its climacteric spiral movement, analyzing its intricate structure is a difficult task that has tested the mettle of John’s most devoted students. Most would agree with Richard Bauckham that “the book of Revelation is an extraordinarily complex literary composition.” David Aune concurs: Revelation is “an elaborately designed and ingeniously crafted literary work.” Indeed, its structure is extremely complicated, quite fascinating – and vigorously debated.

Thus, as Grant Osborne observes: “outlines of Revelation vary perhaps more than any other book of the Bible.” E. S. Fiorenza laments that “one can almost find as many different outlines of the composition as there are scholars studying the book.” After my own several years of researching Rev, I disagree with Fiorenza and Collins: there seem to be more outlines than interpreters!

Aune (notes that “the problem of the literary analysis of Revelation, despite many proposals, remains a matter on which there is no general consensus among scholars.” F. J. Murphy comments that “even today, almost two thousand years after its writing, scholars continue to propose new analyses of Revelation’s structure, but there is still no general consensus on many aspects of its principle organization.”

The Beast of Revelation

by Ken Gentry

A popularly written antidote to dispensational sensationalism and newspaper exegesis. Convincing biblical and historical evidence showing that the Beast was the Roman Emperor Nero Caesar, the first civil persecutor of the Church. The second half of the book shows Revelation’s date of writing, proving its composition as prior to the Fall of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. A thought-provoking treatment of a fascinating and confusing topic.

For more study materials, go to: KennethGentry.com

Eugenio Corsini wisely notes that “the reason for these difficulties is obvious, as we do not have the slightest indication of how the original author wished to subdivide his work.” W. J. Harrington agrees: “Beyond some obvious indications (the septets, for instance) it is not possible to be sure of any structural intent of the author.”

David Barr highlights a likely problem in this regard: “Whereas our concern is to divide the book, John’s concern was to bind it together.”

The Development of Revelation’s Outline

In my commentary I employ only the most basic framework structured around John’s four “in Spirit” (en pneumati) experiences (1:10; 4:2; 17:3; 21:10), three of which are closely aligned with the visionary “come and see” commands (4:1; 17:1; 21:9). This structure highlights the simplest structural feature, presenting the material in four primary visions indicate “major transitions within the whole vision” (Bauckham).

This simple structuring of the book avoids the complexities of wrestling with highly debated framework arguments. Instead, it picks up on this distinctive phrasing that highlights John’s prophetic experience (1:10; 4:2) and Spirit-transport (17:3; 21:10). As M. C. Tenney notes this phrase is significant in that “each occurrence of this phrase locates the seer in a different place.” I select this very basic structuring because it reflects Rev’s drama-form (suggesting the four most important scene changes) and judicial character while avoiding unnecessary complexities and debatable assertions. Let me explain.

The first “in Spirit” section. As he traces the prophetic lawsuit motif in Revelation, Alan Bandy insightfully argues for the judicial implications of John’s “in Spirit” experiences. He points out that the first “in Spirit” section (1:9-3:22) shows John under judicial censure on Patmos to where Rome banishes him. While there Christ directs him to write Revelation and send it to the seven churches (1:11). In the following seven letter-oracles Christ will engage an investigative judgment of the churches.

We may discern this from both Christ’s visionary appearance and his oracles. He appears as the Son of Man with flaming (i.e., dross-burning, searching) eyes and a two-edged (i.e., penetrating) sword (1:14, 16; 2:18, 23; cp. Heb 4:12); then he criticizes and warns the churches (2:4, 5, 14, 16, 20, 24; 3:2-3, 17, 19). Christ’s judicial criticism is designed to show “all the churches” that “I am He who searches the minds and hearts; and I will give to each one of you according your deeds” (2:23). Bandy observes that “the first vision corresponds to the covenant lawsuit speech designed to promote repentance and faithfulness.” Furthermore, I would add that his “in Spirit” experience proleptically involves him in the Day of the Lord judgment (see exposition at 1:10; cp. 6:17; 16:14).

Survey of the Book of Revelation

(DVDs by Ken Gentry)

Twenty-four careful, down-to-earth lectures provide a basic introduction to and survey of the entire Book of Revelation. Professionally produced lectures of 30-35 minutes length.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The second “in Spirit” section. The second “in Spirit” experience escorts John into heaven (4:1-2a) where he sees God’s throne and heavenly courtroom (4:2b-4). There we see the lightning and thunder (4:5) which signify the terrifying theophany from which the judgments flow out against God’s enemies (4:1-16:21) – with important interludes protecting God’s people (7:1-17; 10:1-11:19). While there in the Spirit John witnesses a session of the divine council (4:1-5:14).

The third and fourth “in Spirit” sections. The third (17:1-21:8) and fourth sections (21:9-22:5) have strong introductory parallels, establishing a clear relationship between them and a climax to the whole judicial procedure.

The third section has John “in Spirit” while an angel transports him into the wilderness where he will hear the harlot’s sentence and witness her judgment. The harlot is drunk on the blood of the saints (17:6; 18:24) and intoxicates the nations with her passion to destroy (18:3), so that she deserves a double payback (18:6). Her destruction is sure because “the Lord God who judges her is strong” (18:8, 20). Heaven will praise God’s judgments against her (19:1-3). Her judgment ultimately comes from Christ who appears as the divine warrior (19:11-19).

The fourth “in Spirit” section has one of the seven judgment angels carrying John to a great high mountain where he sees the vindication and reward of the saints (21:9-22:5). In their reward they inhabit the strong, well-protected heavenly Jerusalem come down to earth.

My Decision on Revelation’s Outline

Employing the preceding observations, and since virtually all commentators agree that Revelation has a prologue (1:1-8) and an epilogue (22:6-21), my basic outline will be:

Part I. Introduction (1:1-8)

Part II. In the Spirit on Patmos (1:9-3:22)

Part III. In the Spirit in Heaven (4:1-16:21)

Part IV. In the Spirit in the Wilderness (17:1-21:8)

Part V. In the Spirit on the Mountain (21:9-22:5)

Part VI. Conclusion (22:6-21)

This judicial structuring fits nicely with my understanding of Revelation as focusing on God’s divorce and Israel and his taking of a new bride, the universal Church of Jesus Christ.

September 9, 2025

1 JOHN 2:2 BY B. B. WARFIELD (3)

“Jesus Christ the Propitiation for the Whole World” (3)

“Jesus Christ the Propitiation for the Whole World” (3)

PMW 2025-071 by Benjamin B. Warfield

[Gentry note: This is part 3 of an excellent article by renowned postmillennial Princeton scholar, B. B. Warfield.]

The Meaning of “Propitiation”

The expedient made use of by many commentators in their endeavor to escape from this maze of contradictions is to distinguish between Christ as our “Advocate” and Christ as our “Propitiation,” and to connect actual salvation with him only in the former function. Thus Richard Rothe tells us that “the propitiation in Christ concerns the whole world,” but “only those in Christ have an advocate in Christ,” with the intimation that it is Christ’s advocacy which “makes the efficacy of his propitiation effective before God.” In this view the propitiation is conceived as merely laying a basis for actual forgiveness of sins, and is spoken of therefore rather as “sufficient” than efficacious—becoming efficacious only through the act of faith on the part of the believer by which he secures Christ as his Advocate. This is the view presented by B. F. Westcott also, according to whom Christ is advocate exclusively for Christians, while he is a propitiation for the whole world. His propitiatory death on earth was for all men; his advocacy in heaven is for those only who believe in him. Here, there is a universal atonement taught, with a limited application, contingent on actual faith: “the efficacy of his work for the individual depends upon fellowship with him.”

It is obvious that such a view can be held only at the cost of emptying the conception of propitiation of its properly expiatory content, and shifting the really saving operation of Christ from his “atoning” death on earth to his “intercession” in heaven. Westcott carries out this whole program fully, and by a special doctrine of “sacrifice,” of “blood” and its efficacy, and of “the heavenly High Priesthood of Christ” systematizes this point of view into a definite scheme of doctrine. No support is given this elaborate construction by John; and our present passage is enough to shatter the foundation on which it is built, in common with many other constructions sharing with it the general notion that the atonement is to be conceived as universal while its application is particular, and that we may therefore speak of the sins of the whole world as expiated while believers only enjoy the benefits of this expiation.

He Shall Have Dominion

(paperback by Kenneth Gentry)

A classic, thorough explanation and defense of postmillennialism (600+ pages). Complete with several chapters answering specific objections.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The “advocacy” of our Lord is indeed based on his propitiation. But it is based on it not as if it bore merely an accidental relation to it, and might or might not, at will, follow on it; but as its natural and indeed necessary issue. John introduces the declaration that Christ is—not “was,” the propitiation is as continuous in its effect as the advocacy—our propitiation, in order to support his reference of sinning Christians to Christ as their Advocate with the Father, and give them confidence in the efficacy of his advocacy. The efficacy of the advocacy rests on that of the propitiation not the efficacy of the propitiation on that of the advocacy. It was in the propitiatory death of Christ that John finds Christ’s saving work: the advocacy is only its continuation—its unceasing presentation in heaven.

The propitiation accordingly not merely lays a foundation for a saving operation, to follow or not follow as circumstances may determine. It itself saves. And this saving work is common to Christians and “the whole world.” By it the sins of the one as of the other are expiated, that is to say, as Weiss wishes to express it in Old Testament forms of speech, are “covered in the sight of God.” They no longer exist for God—and are not they blessed whose iniquities are forgiven, and whose sins are covered, to whom the Lord will not reckon sin? It is idle to talk of expounding this passage until we are ready to recognize that according to its express assertion the “whole world” is saved. Its fundamental assumption is that all those for whose sins he is—is, not “was”—the propitiation have in him an Advocate with the Father, prevailingly presenting his “righteousness” to the Father and thereby securing their salvation.

The Question of Universalism

This is, of course, universalism. And it is in determining the precise nature of the universalism that it is, that we arrive at last at John’s real meaning. In declaring that Jesus Christ is a propitiation for the whole world, John certainly does not mean to assert that Christ has made expiation for all the sins of every individual man who has come or will come into being, from the beginning of the race in Adam to its end at the last day.

Baumgarten-Crusius seems to stand almost alone in expressly emphasizing the protensive aspect of the “world”; and he does it in order to avoid admitting that John means to present Christ as the Savior of the whole world extensively considered. John means only, he says, that Christ is a Savior with abiding power for the whole human era; all through the ages he is mighty to save, though he saves only his own. It is much more common silently to assume that by “the whole world” John has in mind the whole race of mankind throughout the entire range of its existence in time: few have the hardihood openly to assert it. It is ordinarily taken for granted (Huther is one of the few who give it explicit expression) that “John was thinking directly of the ‘world’ as it existed in his time.” Huther indeed adds the words: “without however limiting the idea to it,” and thus suggests that John was thinking of the “world” protensively as well as extensively, without explicitly saying so. Clearly in any event it would be impossible to attribute to John teaching to the effect that Christ’s expiatory work concerned only those who happened to be living in his own—or John’s —generation. This would yield a conception of the range of the propitiatory efficacy of our Lord’s death which can be looked upon only as grotesque.

Lord of the Saved

(by Ken Gentry)

A critique of easy believism and affirmation of Lordship salvation. Shows the necessity of true, repentant faith to salvation.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Yet there is nothing in John’s language to justify the attribution to him of a protensive conception of “the whole world” in the sense of the universalists. It seems quite clear that, by “the whole world,” he means primarily the world extensively conceived. It is equally clear, however, that he means neither to confine the efficacy of Christ’s blood to his own generation, nor to maintain that the entirety of contemporary humanity was saved. He knew of those not of his own time who were saved; he knew of children of the devil in his own day. There is a protensive element in his conception of the word. It is however of its protension in the future rather than in the past that he is thinking. He sees the world not only lying on every side of him in space, but very especially as stretching out before him in time. The contrast between it and the little flock of Christians includes thus a contrast of times.

The interpretation of our passage has suffered seriously from a mechanical treatment of its language. We must permit to John the flexibility customary among men in the handling of human speech. When be speaks of Christ as a propitiation “for the whole world,” we cannot either confine his language rigidly to the world of his own day, or expand it with equal rigidity to the extremest limit of the possible connotation of the phrase. He is certainly intending to present Christ as a world-wide Savior by whom nothing less than the world is saved; but it does not follow that he means to affirm that therefore no single man of all who ever live in the world is omitted. He is obviously thinking in the terms of the great phrase he is himself a little later to use, when he declares that the Father has sent the Son “as Savior of the world.” To him Jesus Christ is very expressly the Savior of the whole world: he had come into the world to save not individuals merely, out of the world, but the world itself. It belongs therefore distinctly to his mission that he should take away the sin of the world. It is this great conception which John is reflecting in the phrase, “he is the propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only but for the whole world.”

This must not be diluted into the notion that he came to offer salvation to the world, or to do his part toward the salvation of the world, or to lay such a basis for salvation that it is the world’s fault if it is not saved. John’s thinking does not run on such lines; and what he actually says is something very different, namely that Jesus Christ is a propitiation for the whole world, that he has expiated the whole world’s sins. He came into the world because of love of the world, in order that he might save the world, and he actually saves the world. Where the expositors have gone astray is in not perceiving that this salvation of the world was not conceived by John—any more than the salvation of the individual—accomplishing itself all at once. Jesus came to save the world, and the world will through him be saved; at the end of the day he will have a saved world to present to his father. John’s mind is running forward to the completion of his saving work; and he is speaking of his Lord from the point of view of this completed work. From that point of view he is the Savior of the world.

Conceptions like those embodied in the Parables of the Mustard Seed and the Leaven lay at the back of John’s mind. He perfectly understood that the Church as it was phenomenally present to his observation was but “a little flock.” He as perfectly understood that it was after a while to cover the whole world. And therefore he proclaims Jesus the Savior of the world and declares him a propitiation for the whole world. He is a universalist; he teaches the salvation of the whole world. But he is not an “each and every” universalist he is an eschatological” universalist. He teaches the salvation of the world through a process; it may be— it has proved to be— a long process; but it is a process which shall reach its goal. It is not then “our” sins only which Jesus has expiated—the sins of the “little flock,” now living within the range almost of John’s physical vision. He has expiated also the sins of “the whole world”; and at the end, therefore we shall be nothing less than a world saved by him. The contrast between the “our” and “the world” in John’s mind, therefore, is at bottom the contrast between the smallness of the beginnings and the greatness of the end of the Christian development.

And what his declaration is, at its core, is thus only another of those numerous —prophecies, shall we say? or assertions?—which meet us throughout the apostolic teaching, of the ultimate conquest of the world by Christ. Christ, he tells his “little flock,” is the “propitiation for our sins”; in him “we” have found a full salvation. But he is not willing to stop there. His glad eyes look out on a saved world. “And not for ours only,” he adds, “but also for the whole world.” We are a “little flock” now: tomorrow we shall be the world. We are but the beginnings: the salvation of the world is the end. And it is not this only, but that, that Christ has purchased with his precious blood. The light that is perceptible now only within the narrow limits of the “little flock” has in it a potency of illumination which no bounds can confine: it, “the real light,” is “already shining”—and before it John sees “the darkness” already “passing away.”

It is not merely a world-wide gospel with which he knows himself entrusted: it is a world-wide salvation which he is called to proclaim. For Jesus Christ is the Savior not of a little flock merely, but of the world itself: and the end to which all things are working together is nothing other than a saved world. At the end of the day there will stand out in the sight of all a whole world, for the sins of which Christ’s blood has made effective expiation, and for which he stands as Advocate before the Father.

September 5, 2025

1 JOHN 2:2 BY B. B. WARFIELD (2)

“Jesus Christ the Propitiation for the Whole World” (2)

“Jesus Christ the Propitiation for the Whole World” (2)

PMT 2025-070 by Benjamin B. Warfield

[Gentry note: This is part 2 of an excellent article by renowned postmillennial Princeton scholar, B. B. Warfield.]

“And he is the propitiation for our sins; and not for ours only, but also for the whole world.”

(1 John 2:2)

The Problem of “the World”

The search for John’s meaning naturally begins with an attempt to ascertain what he intends by “the world.” He sets it in contrast with an “our” by which primarily his readers and himself are designated: “And he is himself a propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only but for the whole world.” John’s readers apparently are immediately certain Christian communities in Asia Minor; and it is possible to confine the “our” strictly to them. In that case it is not impossible to interpret “the whole world,” which is brought into contrast with the Christians specifically of Asia Minor, as referring to the whole body of Christians extended throughout the world.

A certain measure of support for such an interpretation may be derived from such a passage as Colossians 1:6, where “the word of the truth of the gospel” is spoken of as “in all the world,” or as Colossians 1:23, where the gospel is said to have been “preached in all creation under heaven.” In these passages the world-wide gospel seems to be contrasted with the heresies which were troubling the Colossian Christians and which are thus branded as a merely local phenomenon. In something of the same way, the world-wide extension of the people of God may be thought to be brought into contrast by John with the local churches he is addressing; and his purpose may be supposed to be to remind these local churches that they have no monopoly of the gospel. The propitiatory efficiency of Christ’s blood is not confined to the sins of the Asian Christians, but is broad enough to meet the needs of all in like case with them through-out the whole world. Christ is no local Savior, and all, everywhere, who confess their sins will find him their righteous advocate, whose expiatory blood cleanses them from every sin. On this interpretation we are brought to much the same point of view as that of Augustine and Bede, of Calvin and Beza, who understand by “the whole world” “the churches of the elect dispersed through the whole world”; and by the declaration that Jesus Christ is “a propitiation for the whole world,” that in his blood all the sins of all believers throughout the world are expiated.[image error]For more information and to order click here.

" data-image-caption="" data-medium-file="https://postmillennialworldview.com/w..." data-large-file="https://postmillennialworldview.com/w..." class="alignright size-thumbnail wp-image-254" src="https://postmillennialworldview.com/w..." alt="When Shall These Things Be? A Reformed Response to Hyperpreterism" width="95" height="150" />When Shall These Things Be? A Reformed Response to Hyperpreterism

(ed. by Keith Mathison)

A reformed response to the aberrant HyperPreterist theolgy.

Gentry’s chapter critiques HyperPreterism from an historical and creedal perspective.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

When the assumptions on which this view of the passage is founded are scrutinized, however, they cannot be said particularly to commend themselves. John is certainly addressing a specific body of readers, and no doubt has them quite distinctively in mind when he speaks to them in the tender words, “My little children, I am writing this to you, that ye sin not.” But the affirmations he makes do not seem to be affirmations applicable only to them, or to be intended to be understood as spoken only of them. This is already apparent from his identifying himself with them in these affirmations. “We have an Advocate,” he says; “he is a propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only.” If it is not impossible that he means only “you and I,” “for your and my,” with the strictest confinement of the “you” and “your” to those he was immediately addressing, it is nevertheless very unlikely that this is the case.

He appears, on the contrary, to be reminding them of universal Christian privileges, in which they and he shared precisely for the reason that they were universally Christian. In that case the “we” and “our” refer to the whole Christian community—“we Christians” have “our, namely Christians’” sins; and “the whole world” is brought in some way into contrast with the Christian body as a whole. The strength of the assertion of universality in the contrasted phrase—“but also for the whole world”—falls in with this appearance. Why should the Apostle with such emphasis— why should he at all— assure his readers that the privileges they enjoyed as Christians—in common with him because they were both Christians— were also enjoyed by all other Christians,—by all other Christians throughout the whole world? Would it not be a matter of course, scarcely calling for such explicit assertion, that other Christians like themselves enjoyed the benefits of the expiatory death of their Lord? That was precisely what it was to be a Christian.

It is not surprising accordingly that the greater number of the commentators agree that the “we” of our passage is the whole body of believers, with which “the whole world” is set in contrast. That carries with it, of course, that in some sense our Lord is declared to have made propitiation not only for the sins of believers, thought of by John as actually such, but also for mankind at large. If we do not attempt the impossible feat of emptying the conception of “propitiation” of its content, this means that in some sense what is called a “universal atonement” is taught in this passage. The expiatory efficiency of Christ’s blood extends to the entire race of mankind. It may seem, then, the simplest thing just to recognize that John here represents Christ as by his atoning death expiating all the sins of all mankind— all of them without exception. This is the line of exposition which is taken, for instance, by Bernhard Weiss. “Precisely this passage shows plainly,” he writes, “that the whole body of the world’s sin is covered in the sight of God, that is to say expiated, by the death of Christ.”

That this method of expounding the passage is not so simple, however, as it might at first sight appear, is already made clear enough by the remainder of the sentence in which Weiss gives expression to it. It runs: “What brings unbelievers to death is no longer their sin (expiated in the death of Christ), but their rejection of the divinely appointed mediator of salvation.” From this it appears that the expiation of the sins of the world does not save the world. There still remain those who perish: and those who perish, as John contemplated them looking out from the bosom of the little flock of the Church, constituted the immensely greater part of mankind spread out to his view, in one word just “the world” of which he is in the act of declaring that its sins are expiated in the blood of Christ. John speaks of this expiation as a great benefit brought to the world by Christ, or, to put it in its true light, as the great benefit, in comparison with which no other benefit deserves consideration.

Amillennialism v. Postmillennialism Debate

(DVD by Gentry and Gaffin)

Formal, public debate between Dr. Richard Gaffin (Westminster Theological Seminary)

and Kenneth Gentry at the Van Til Conference in Maryland.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Yet it would puzzle us to point out of what benefit it is to the world. The world, to all appearance, remains precisely as it was before. It is very clear that the world was not conceived by John as a redeemed world. We are not to love it, nor the things in it. We are rather to renounce it, as an inimical power. Nay, John declares roundly that the whole world—this whole world which we are invited to think of as having had all its sins expiated by the blood of Christ—“lieth in the evil one.” It is difficult to understand how a world all whose sins have been, and are continually as they emerge being—for that is the force of the representation—washed away in the blood of Christ, can still be lying in the evil one; that is to say, as A. Plummer expounds this declaration, still “remains in the power” of the evil one, “has not passed over, as Christians have done, out of death into life; but abides in the evil one, who is its ruler, as the Christian abides in Christ.” What we are asked to believe is nothing less than that the John who places the world and Christian in directly contrary relations to Christ, nevertheless in our present passage places them in precisely the same relation in Christ.

Nor is it easy to understand what can be meant by saying that men, all whose sins, as they occasionally emerge (“and he is,” not was, “a propitiation”) are covered from the sight of God by the death of Christ, nevertheless perish; and that because of rejection of the divinely appointed mediator of salvation. Is not the rejection of Jesus as our propitiation a sin? And if it is a sin, is it not like other sins, covered by the death of Christ? If this great sin is excepted from the expiatory efficacy of Christ’s blood, why did not John tell us so, instead of declaring without qualification that Jesus Christ is the propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only but for the whole world? And surely it would be very odd if the sin of rejection of the Redeemer were the only condemning sin, in a world the vast majority of the dwellers in which have never heard of this Redeemer, and nevertheless perish. On what ground do they perish, all their sins having been expiated?

(To be continued)

September 2, 2025

1 JOHN 2:2 BY B. B. WARFIELD (1)

“Jesus Christ the Propitiation for the Whole World” (1)

“Jesus Christ the Propitiation for the Whole World” (1)

PMW 2025-069 by Benjamin B. Warfield

[Gentry note: This is an excellent article by renowned postmillennial Princeton scholar, B. B. Warfield.]

“And he is the propitiation for our sins; and not for ours only, but also for the whole world.”

(1 John 2:2)

As a means of comforting Christians distressed by their continued lapses into sin, John, in the opening words of the second chapter of his first Epistle, is led to assure them that “we have an Advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ, a Righteous One”; and by way of showing how prevailing his advocacy is, to add, “And he is himself a propitiation for our sins.” There he might well have stopped. But, without obvious necessity for his immediate purpose, he adds this great declaration: “And not for ours only, but also for the whole world.” That by these words the propitiation wrought by Christ, of which we have continual need, and on which we continually draw in our need, is exalted by ascribing to it, in some sense, a universal efficacy, is clear enough. But the commentators, first and last, have not found it easy to make plain to themselves the precise nature of the universalism assigned therein to our Lord’s propitiatory sacrifice.

Difficulties for Commentators

Readers of old John Cotton’s practical notes on First John, for example, will not fail to observe that he moves with a certain embarrassment in his exposition of this universalism. He has a number of things, in themselves of value, to say about it; but he appears to find most satisfaction in the suggestion that although Christ by his expiatory death has bought for his people some things—and these the most important things—which he has not bought for all men, yet there are some most desirable things also which he has bought for all men. This, however, is certainly not what John says. It admits of no doubt that John means to say that the Christians whom he was addressing, and with whom he identifies himself—they and he alike—enjoy no privilege with reference to the propitiation of Christ, which is not enjoyed by them in common with “the whole world.” They—and he with them—are not to be disheartened by their sins, he says, because these sins have been expiated by the blood of Christ; by which have been expiated indeed, not their sins only but also those of “the whole world.” The “whole world” is not made in some general and subsidiary sense a beneficiary of Christ’s atoning death, but in this specific and highest sense — the expiation of its sins. Its sins have been as really and fully expiated as those of the Christians John was addressing, and as his own.

Thine Is the Kingdom

(ed. by Ken Gentry)

Contributors lay the scriptural foundation for a biblically-based, hope-filled postmillennial eschatology, while showing what it means to be postmillennial in the real world.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The most “modern” of modern expositors are as much at sea in the face of the universalism of this assertion as any of the older and presumably less instructed ones could be. Thus Otto Baumgarten simply declines to attempt its exposition. We do not know what John means, he says; we lack the necessary information to enable us to understand him. It may sound very fine to say that John teaches here that no shadow is cast on God’s holiness by the exhibition of partiality on his part for individuals; that he rebukes those who, in egotistic and sentimental religiosity, or in selfish anxiety for their own salvation, would draw apart from their fellows.

But difficulties remain. Experience scarcely encourages us to think that all without exception are sharers in Christ’s salvation; it rather bears out our Lord’s declaration that the gate is narrow and the way straitened that leads to life and few there be that find it. And John! Is not the whole world to him a massa corrupta—a “darkness” which does not “apprehend” “the light”? How we can harmonize the three passages— John 1:29, which speaks of taking away the sin of the world; John 3:16, “God so loved the world”; and this, declaring that Christ has made propitiation for the sins of the world—with John’s sharp dualism of Light and Darkness, does not appear.

Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond

(ed. by Darrell Bock)

Presents three views on the millennium: progressive dispensationalist, amillennialist, and reconstructionist postmillennialist viewpoints. Includes separate responses to each view.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Perhaps John is only repeating with thoughtless neglect of their inconsequence the elements of Paul’s doctrine of propitiation. Perhaps, mystical-speculative thinker that he is, he means to suggest that in Jesus’ purpose or general feeling his redemption was for the whole sinful world, but only those have found in him an actual Redeemer or Intercessor to whom he has given power to become Children of the Light. Perhaps it is, on the other hand, the missionary instinct of the Church, which declares here that no limits are to be set to the spread of salvation over the whole world—in contrast to the Gnostic confinement of it to certain gifted individuals. We can form many conjectures; we can reach no assurance.

(To be continued)

August 29, 2025

WHEN DOES THE ‘ALREADY’ END?

PMW 2025-072 by Ardel Caneday

Gentry Note:

This article on the Two-Age redemptive historical scheme is quite helpful. After reading it, I wrote to Dr. Caneday (my old Grace Seminary friend) to let him know that not all postmills agree with Wilson and Brito on the matter. In fact, I follow Bahnsen in subscribing to Vos’ Two-Age view while maintaining the posmillennial hope. I am currently working on a book on the topic. If you would like to financial contribute to this project, please see my final note below. Even if you would not like to contribute, I hope you will before my hitmen set sail towards your house. But now for Caneday’s article:

“Already But Not Yet”: When Does the “Already” End? When Christ Returns or When Jerusalem’s Temple Was Destroyed?

by Ardel Caneday

Within my lifetime, not only academics but lay people also have become increasingly familiar with “the already but not yet”—the biblical concept of the overlapping of two ages—the present age and the age to come. This became evident when “Progressive Dispensationalism” emerged with the publication of Dispensationalism, Israel and the Church (1992). A feature that distinguishes this newer form of dispensationalism is the belief that Christ Jesus already reigns, fulfilling the promise to David (Psalm 110), but not yet are all his enemies put under his feet. Hence, concerning Christ’s reign, “inauguration is present, but consummation is not.”[1] While distinguishing their view from “Classical Dispensationalism,” they also contended that their “formulation of ‘the already, not yet’ kingdom” was different from George Ladd’s.[2] Nevertheless, they set in motion rapprochement with non-dispensationalists that accelerated profitable conversations among scholars from both views throughout the past thirty years.[3]

“Already But Not Yet”—The Overlapping of Ages Between Christ’s Comings

Dispensationalism, Israel and the Church (edited by Craig A. Blaising and Darrell L. Bock) engages with George Ladd, but never mentions Geerhardus Vos. Ladd learned from Vos “the already but not yet” structure of the New Testament writers’ presentation of Christ’s inaugurated reign that awaits consummation. Vos extensively developed Christ’s “already but not yet” dominion in The Pauline Eschatology, where “eschatology” is not a reference to “the last things” as a systematic theology category. Rather, Vos uses “eschatology” to encompass the entirety of the Apostle Paul’s theological teaching concerning redemption in Christ Jesus.[4] Thus, Vos teaches us to recognize that when the OT prophets saw in advance the Messiah’s sufferings and subsequent glory, they were not given the insight that the salvation they prophesied would arrive not in one, but two phases (cf. 1 Pet. 1:10–12). So, at the Messiah’s advent, the glorious realm the prophets anticipated would reach its exhaustive fulfillment in fact did not end. Instead, Christ begins this new creation (Gal. 6:15; 2 Cor. 5:17). He set in motion the age to come without ending this present evil age (Gal. 1:4; Eph. 1:21). All who are in Christ Jesus are already inhabiting the age to come in as much as God the Father “has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places” (Eph. 1:3).

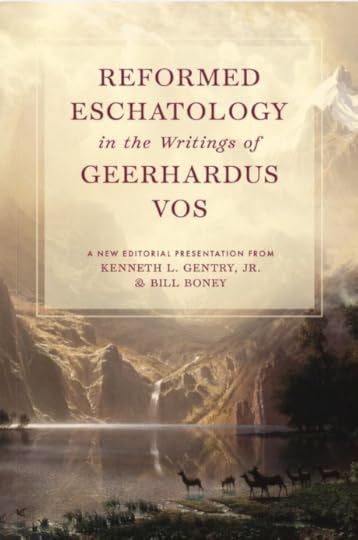

Reformed Eschatology in the Writings of Geerhardus Vos

Ed. by Ken Gentry and Bill Boney

This is a collection of several key eschatological studies by the renowned Reformed theologian Geehardus Vos. We have modernized Vos’ grammar and syntax and updated his layout style according to modern publishing conventions (shorter sentences and paragraphs). We did this without changing any of Vos’ arguments.

For more information on this new Vos work or to order it, see:

https://www.kennethgentry.com/reformed-eschatology-in-the-writings-of-geerhardus-vos/

New Testament readers, whether Reformed or non-Reformed, Protestant or Catholic, have recognized this “already but not yet” structure and dynamic. This “already but not yet” dynamic concerns the presence of the future which is bound up fully with Christ’s advent. Thus, we should not speak of the “already but not yet” as a matter of degrees. It is not as if the coming age of salvation (brought forward into the midst of history when Christ came) is already partially here and partially not yet come. Instead, the perspective the NT writers present is that Christ Jesus has already inaugurated the new creation, which he will fully consummate when he returns. Thus, the glorious blessings of the coming age come to us in two phases. The already phase is anticipatory of the not yet phase. As the new moon anticipates the full moon, Christ’s first coming is a portent of his second advent (Acts 1:11). We are already inhabiting the inaugurated phase of the promised age of salvation while we await the consummated phase when Christ returns. We already experience the resurrection life in the resurrected Christ even as we inhabit this present evil age (Gal 1:4). By way of the preaching of the good news, through faith in Christ, we already receive the justifying verdict in advance of the Day of Judgment as we “eagerly wait for the hope of righteousness” (Gal. 5:5; cf. Matt. 12:36-37).

Focusing on the Apostle Paul’s letters prompts us not only to recognize how frequently we come upon “the already by not yet” dynamic but also how instructive it is. Consider the following.

• We are already adopted in Christ Jesus (Rom. 8:15), but not yet adopted (Rom. 8:23).

• We are already redeemed in Christ Jesus (Eph. 1:7), but not yet redeemed (Eph. 4:30).

• We are already sanctified in Christ Jesus (1 Cor. 1:2), but not yet sanctified (1 Thess. 5:23–24).

• We are already saved in Christ Jesus (Eph. 2:8), but not yet saved (Rom. 5:9; 13:11);

• We are already raised with Christ Jesus (Eph. 2:6), but not yet raised (1 Cor. 15:52).[5]

Vos teaches us, then, to conceive of two ages or two realms coexisting with one another since the advent of Christ Jesus. With his resurrection, Christ brought forward the powers of the coming age (cf. Heb. 6:5), including resurrection and judgment, activating these powers within this present age.[6] Many have reproduced Vos’s charts that portray how the age to come now overlaps the present age since the advent of our Lord.[7] Readers of the ESV Study Bible will find a variation of Vos’s two diagrams.[8] Below is my own representation of Vos’s portrayal of how the OT prophets anticipated the salvation that Messiah’s coming would bring, followed by the structure updated by Christ’s coming.

Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond

(ed. by Darrell Bock)

Presents three views on the millennium: progressive dispensationalist, amillennialist, and reconstructionist postmillennialist viewpoints. Includes separate responses to each view. Ken Gentry provides the postmillennial contribution.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

“Already But Not Yet”—Only Forty Years of Overlapping Ages?

Recently, partial preterists, who embrace post-millennialism, have modified this portrayal of the NT’s teaching concerning “the already and the not yet.” Consider, last month’s podcast with Doug Wilson concerning the nature of Christian Nationalism. Among various pertinent questions asked of Doug Wilson, David Schrock inquired,

“What for you is the mission of the church and, connected to that, how does your understanding of the two ages fit with that? Is there an already and not yet understanding? Certainly in things that I’ve read from you, you’ve said the overlap of the ages took place between the ascension of Christ and the destruction of Jerusalem. Help us understand that and the mission of the church (Interview with Doug Wilson on Christian Nationalism).”

Doug Wilson replied,

Okay, so very quickly on the ages. I think the Old Testament era—I call it the Judaic age—ended cataclysmically in 70 A.D. I think the Christian Aeon, or the Christian Age, was inaugurated 40 years before the Judaic Age ended. It was like a baton exchange in a relay race.

So, there were roughly 40 years when the two ages were running concurrently, and then the temple was destroyed, and we were into the Christian aeon. I would say that the already-not yet aspect of it has to do with the eternal age to come, so after the Lord Jesus returns. The Lord has been raised from the dead so that the end of the world happened in the middle of history. That’s the already. But then the general resurrection of the dead is the not yet.

So that’s the general pattern of the sketch for the ages.

Given Wilson’s response, the chart below illustrates what he believes concerning the “already but not yet”:

On his own blog, Wilson fills out some details concerning “the not yet” aspect. He explains that because of Adam’s disobedience, the Creator afflicted the created order with corruption. Creation’s liberation from this bondage will come about only when we, Christ’s people, receive our “not yet” adoption as God’s sons (Rom. 8:23). Thus, the entire creation groans with the pains of childbirth, pregnant with expectation, eagerly “longing for the revealing of the sons of God” (Rom. 8:19). Wilson says,

This is the world that is pregnant with a future glory. So we do not believe that an external force is going to come down at the end of time and zap everything to make it different. We believe He already came down, and He already rose in the middle of history, such that things are already different—just as a pregnant woman is already a mother and not yet a mother. The transformation of the cosmic order is working its way out from the inside. A decaying world was infected with radical life and the infection site was a tomb outside Jerusalem.

Have We Missed the Second Coming:

A Critique of the Hyper-preterist Error

by Ken Gentry

This book offers a brief introduction, summary, and critique of Hyper-preterism. Don’t let your church and Christian friends be blindfolded to this new error. To be forewarned is to be forearmed.

For more Christian educational materials: www.KennethGentry.com

Wilson believes the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple ended what he calls “the Judaic age” in A.D. 70. Consequently, the overlapping of the two ages spanned only about forty years. So, Wilson significantly reconfigures Vos’s conception of the two realms or ages. His version of Vos’s schema terminates the line representing this present age at A.D. 70, instead of at Christ’s second advent. Wilson relabels the time of Christ’s death and resurrection to the destruction of the temple in 70 A.D. as “the Judaic age,” instead of “this present age.” Likewise, he labels the time of Christ’s death and resurrection until the second coming as “the Christian Age,” instead of “the Age to Come.” Hence, his diagram does not capture the intersection of the vertical and horizontal dimensions as Vos’s does. Nevertheless, Wilson insists that Christ’s resurrection already invades the present with transformative power.

A decade ago, Uri Brito wondered how using the language of “already but not yet” was beneficial to the postmillennial explanation of “the victorious promise of the gospel.” He suggested that . . . .

To read full article with footnotes: https://christoverall.com/article/concise/already-but-not-yet-when-does-the-already-end-when-christ-returns-or-when-jerusalems-temple-was-destroyed/

GOODBIRTH AND THE TWO AGES

I am currently researching a technical study on the concept of the Two Ages in Scripture. This study is not only important for understanding the proper biblical concept of the structure of redemptive history. But it is also absolutely essential for fully grasping the significance of the Disciples’ questions in Matthew 24:3, which spark the Olivet Discourse. This book will be the forerunner to a fuller commentary on the Olivet Discourse in Matthew’s comprehensive presentation. This issue must be dealt with before one can seriously delve into the Discourse itself.

If you would like to support me in my research, I invite you to consider giving a tax-deductible contribution to my research and writing ministry: GoodBirth Ministries. Your help is much appreciated! https://www.paypal.com/donate/?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=4XXFLGKEQU48C&ssrt=1740411591428

When Does the “Already” End?

PMW 2025-072 by Ardel Caneday

Gentry Note:

This article on the Two-Age redemptive historical scheme is quite helpful. After reading it, I wrote to Dr. Caneday (my old Grace Seminary friend) to let him know that not all postmills agree with Wilson and Brito on the matter. In fact, I follow Bahnsen in subscribing to Vos’ Two-Age view while maintaining the posmillennial hope. I am currently working on a book on the topic. If you would like to financial contribute to this project, please see my final note below. Even if you would not like to contribute, I hope you will before my hitmen set sail towards your house. But now for Caneday’s article:

“Already But Not Yet”: When Does the “Already” End? When Christ Returns or When Jerusalem’s Temple Was Destroyed?

by Ardel Caneday

Within my lifetime, not only academics but lay people also have become increasingly familiar with “the already but not yet”—the biblical concept of the overlapping of two ages—the present age and the age to come. This became evident when “Progressive Dispensationalism” emerged with the publication of Dispensationalism, Israel and the Church (1992). A feature that distinguishes this newer form of dispensationalism is the belief that Christ Jesus already reigns, fulfilling the promise to David (Psalm 110), but not yet are all his enemies put under his feet. Hence, concerning Christ’s reign, “inauguration is present, but consummation is not.”[1] While distinguishing their view from “Classical Dispensationalism,” they also contended that their “formulation of ‘the already, not yet’ kingdom” was different from George Ladd’s.[2] Nevertheless, they set in motion rapprochement with non-dispensationalists that accelerated profitable conversations among scholars from both views throughout the past thirty years.[3]

“Already But Not Yet”—The Overlapping of Ages Between Christ’s Comings

Dispensationalism, Israel and the Church (edited by Craig A. Blaising and Darrell L. Bock) engages with George Ladd, but never mentions Geerhardus Vos. Ladd learned from Vos “the already but not yet” structure of the New Testament writers’ presentation of Christ’s inaugurated reign that awaits consummation. Vos extensively developed Christ’s “already but not yet” dominion in The Pauline Eschatology, where “eschatology” is not a reference to “the last things” as a systematic theology category. Rather, Vos uses “eschatology” to encompass the entirety of the Apostle Paul’s theological teaching concerning redemption in Christ Jesus.[4] Thus, Vos teaches us to recognize that when the OT prophets saw in advance the Messiah’s sufferings and subsequent glory, they were not given the insight that the salvation they prophesied would arrive not in one, but two phases (cf. 1 Pet. 1:10–12). So, at the Messiah’s advent, the glorious realm the prophets anticipated would reach its exhaustive fulfillment in fact did not end. Instead, Christ begins this new creation (Gal. 6:15; 2 Cor. 5:17). He set in motion the age to come without ending this present evil age (Gal. 1:4; Eph. 1:21). All who are in Christ Jesus are already inhabiting the age to come in as much as God the Father “has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places” (Eph. 1:3).

Reformed Eschatology in the Writings of Geerhardus Vos

Ed. by Ken Gentry and Bill Boney

This is a collection of several key eschatological studies by the renowned Reformed theologian Geehardus Vos. We have modernized Vos’ grammar and syntax and updated his layout style according to modern publishing conventions (shorter sentences and paragraphs). We did this without changing any of Vos’ arguments.

For more information on this new Vos work or to order it, see:

https://www.kennethgentry.com/reformed-eschatology-in-the-writings-of-geerhardus-vos/

New Testament readers, whether Reformed or non-Reformed, Protestant or Catholic, have recognized this “already but not yet” structure and dynamic. This “already but not yet” dynamic concerns the presence of the future which is bound up fully with Christ’s advent. Thus, we should not speak of the “already but not yet” as a matter of degrees. It is not as if the coming age of salvation (brought forward into the midst of history when Christ came) is already partially here and partially not yet come. Instead, the perspective the NT writers present is that Christ Jesus has already inaugurated the new creation, which he will fully consummate when he returns. Thus, the glorious blessings of the coming age come to us in two phases. The already phase is anticipatory of the not yet phase. As the new moon anticipates the full moon, Christ’s first coming is a portent of his second advent (Acts 1:11). We are already inhabiting the inaugurated phase of the promised age of salvation while we await the consummated phase when Christ returns. We already experience the resurrection life in the resurrected Christ even as we inhabit this present evil age (Gal 1:4). By way of the preaching of the good news, through faith in Christ, we already receive the justifying verdict in advance of the Day of Judgment as we “eagerly wait for the hope of righteousness” (Gal. 5:5; cf. Matt. 12:36-37).

Focusing on the Apostle Paul’s letters prompts us not only to recognize how frequently we come upon “the already by not yet” dynamic but also how instructive it is. Consider the following.

• We are already adopted in Christ Jesus (Rom. 8:15), but not yet adopted (Rom. 8:23).

• We are already redeemed in Christ Jesus (Eph. 1:7), but not yet redeemed (Eph. 4:30).

• We are already sanctified in Christ Jesus (1 Cor. 1:2), but not yet sanctified (1 Thess. 5:23–24).

• We are already saved in Christ Jesus (Eph. 2:8), but not yet saved (Rom. 5:9; 13:11);

• We are already raised with Christ Jesus (Eph. 2:6), but not yet raised (1 Cor. 15:52).[5]

Vos teaches us, then, to conceive of two ages or two realms coexisting with one another since the advent of Christ Jesus. With his resurrection, Christ brought forward the powers of the coming age (cf. Heb. 6:5), including resurrection and judgment, activating these powers within this present age.[6] Many have reproduced Vos’s charts that portray how the age to come now overlaps the present age since the advent of our Lord.[7] Readers of the ESV Study Bible will find a variation of Vos’s two diagrams.[8] Below is my own representation of Vos’s portrayal of how the OT prophets anticipated the salvation that Messiah’s coming would bring, followed by the structure updated by Christ’s coming.

Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond

(ed. by Darrell Bock)

Presents three views on the millennium: progressive dispensationalist, amillennialist, and reconstructionist postmillennialist viewpoints. Includes separate responses to each view. Ken Gentry provides the postmillennial contribution.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

“Already But Not Yet”—Only Forty Years of Overlapping Ages?

Recently, partial preterists, who embrace post-millennialism, have modified this portrayal of the NT’s teaching concerning “the already and the not yet.” Consider, last month’s podcast with Doug Wilson concerning the nature of Christian Nationalism. Among various pertinent questions asked of Doug Wilson, David Schrock inquired,

“What for you is the mission of the church and, connected to that, how does your understanding of the two ages fit with that? Is there an already and not yet understanding? Certainly in things that I’ve read from you, you’ve said the overlap of the ages took place between the ascension of Christ and the destruction of Jerusalem. Help us understand that and the mission of the church (Interview with Doug Wilson on Christian Nationalism).”

Doug Wilson replied,

Okay, so very quickly on the ages. I think the Old Testament era—I call it the Judaic age—ended cataclysmically in 70 A.D. I think the Christian Aeon, or the Christian Age, was inaugurated 40 years before the Judaic Age ended. It was like a baton exchange in a relay race.

So, there were roughly 40 years when the two ages were running concurrently, and then the temple was destroyed, and we were into the Christian aeon. I would say that the already-not yet aspect of it has to do with the eternal age to come, so after the Lord Jesus returns. The Lord has been raised from the dead so that the end of the world happened in the middle of history. That’s the already. But then the general resurrection of the dead is the not yet.

So that’s the general pattern of the sketch for the ages.

Given Wilson’s response, the chart below illustrates what he believes concerning the “already but not yet”:

On his own blog, Wilson fills out some details concerning “the not yet” aspect. He explains that because of Adam’s disobedience, the Creator afflicted the created order with corruption. Creation’s liberation from this bondage will come about only when we, Christ’s people, receive our “not yet” adoption as God’s sons (Rom. 8:23). Thus, the entire creation groans with the pains of childbirth, pregnant with expectation, eagerly “longing for the revealing of the sons of God” (Rom. 8:19). Wilson says,

This is the world that is pregnant with a future glory. So we do not believe that an external force is going to come down at the end of time and zap everything to make it different. We believe He already came down, and He already rose in the middle of history, such that things are already different—just as a pregnant woman is already a mother and not yet a mother. The transformation of the cosmic order is working its way out from the inside. A decaying world was infected with radical life and the infection site was a tomb outside Jerusalem.

Have We Missed the Second Coming:

A Critique of the Hyper-preterist Error

by Ken Gentry

This book offers a brief introduction, summary, and critique of Hyper-preterism. Don’t let your church and Christian friends be blindfolded to this new error. To be forewarned is to be forearmed.

For more Christian educational materials: www.KennethGentry.com

Wilson believes the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple ended what he calls “the Judaic age” in A.D. 70. Consequently, the overlapping of the two ages spanned only about forty years. So, Wilson significantly reconfigures Vos’s conception of the two realms or ages. His version of Vos’s schema terminates the line representing this present age at A.D. 70, instead of at Christ’s second advent. Wilson relabels the time of Christ’s death and resurrection to the destruction of the temple in 70 A.D. as “the Judaic age,” instead of “this present age.” Likewise, he labels the time of Christ’s death and resurrection until the second coming as “the Christian Age,” instead of “the Age to Come.” Hence, his diagram does not capture the intersection of the vertical and horizontal dimensions as Vos’s does. Nevertheless, Wilson insists that Christ’s resurrection already invades the present with transformative power.

A decade ago, Uri Brito wondered how using the language of “already but not yet” was beneficial to the postmillennial explanation of “the victorious promise of the gospel.” He suggested that . . . .

To read full article with footnotes: https://christoverall.com/article/concise/already-but-not-yet-when-does-the-already-end-when-christ-returns-or-when-jerusalems-temple-was-destroyed/

GOODBIRTH AND THE TWO AGES

I am currently researching a technical study on the concept of the Two Ages in Scripture. This study is not only important for understanding the proper biblical concept of the structure of redemptive history. But it is also absolutely essential for fully grasping the significance of the Disciples’ questions in Matthew 24:3, which spark the Olivet Discourse. This book will be the forerunner to a fuller commentary on the Olivet Discourse in Matthew’s comprehensive presentation. This issue must be dealt with before one can seriously delve into the Discourse itself.

If you would like to support me in my research, I invite you to consider giving a tax-deductible contribution to my research and writing ministry: GoodBirth Ministries. Your help is much appreciated! https://www.paypal.com/donate/?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=4XXFLGKEQU48C&ssrt=1740411591428

August 26, 2025

THE CENTER-POINT AND THE TWO AGES

Cullmann (pp. 81–84)We have seen that the Biblical time line divides into three sections: time before the Creation; time from the Creation to the Parousia; time after the Parousia. Even in Judaism we find interwoven with this threefold division, which is never discarded, the twofold division into this age and the coming one — a division that goes back to Parsiism. In this Jewish two-fold division everything is viewed from the point of view of the future. The decisive mid-point of the two-part time line here as the future coming of the Messiah, the coming appears of the Messianic time of salvation, with all its miracles. At that point we find in Judaism the great dividing point that separates the entire course of events into the two halves. This accordingly means that for Judaism the mid-point of the line which signifies salvation lies in the future.The chronologically new thing which Christ brought for the faith of Primitive Christianity consists in the fact that for the believing Christian the mid-point, since Easter, no longer lies in the future. This recognition is of immense importance, and all further considerations concerning the lapse of time lose their fundamental significance for the Primitive Church in view of the completely revolutionary assertion, which is shared by the entire Primitive Christian Church, that the mid-point of the process has already been reached.

Gentry note: As I research my book on the Two-Age view of redemptive history, I have found an older work by Oscar Cullmann quite insightful and valuable. It was originally published in 1950, then as a third edition in 1962. The post below is from pages 81–84 of his book, Christ and Time.

Olivet Discourse Made Easy

(by Ken Gentry)Verse-by-verse analysis of Christ’s teaching on Jerusalem’s destruction in Matt 24. Shows the great tribulation is past, having occurred in AD 70, and is distinct from the Second Advent at the end of history. Provides exegetical reasons for a transition from AD 70 to the Second Advent at Matthew 24:36.See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.comWe must constantly keep in view this difference between Judaism and Primitive Christianity, because it is decisive for our understanding of the Christian division of time. The mid-point of time is no longer the future coming of the Messiah, but rather the historical life and work ofJesus Christ, already concluded in the past. We now see that the new feature in the Christian conception of time, as compared with Jewish conception, is to be sought in the division of time. The conception of time as such is not different, for in both cases we have to do with the linear concept of time, in which the divine redemptive history takes place upon a progressing line. Common to both is also the threefold division mentioned at the opening of the chapter. Furthermore, in both cases that threefold division is cut across by a twofold division into this and the coming age.The radical, momentous contrast has to do with this twofold division. It alone is decisive, because the first section of the threefold division, that one before Creation, actually never is the object of Biblical revelation and thought, and appears only marginally in the New Testament. In Judaism, there is only the one mid-point, which lies in the future and coincides with the dividing point between the present and the coming age. This division is not abandoned in the thought of primitive Christianity; it is rather intersected by a new one. For here the mid-point between the present and the coming age comes to lie on a definite point which lies at a more or less short distance (depending on the individual author) before the old dividing point. And yet this old dividing point is still valid. [1]

Olivet Discourse Made Easy