Kenneth L. Gentry Jr.'s Blog, page 110

July 1, 2015

VICTORY: THEN COMES THE END

PMT 2015-079 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-079 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

Postmillennialism differs from the other evangelical eschatologies in a very important respect: Postmillennialism is optimistic about the progress of the gospel in history. We believe that Christ’s victory on the cross will exercise a tremendous influence in history — before the end, before the return of Christ.

We see this throughout the Scriptural record. Some amillennialists charge that postmillennialism is built solely on Old Testament texts, and that its optimistic outlook cannot be found in the New Testament. But that is absolutely mistaken. Let us consider one text in Paul as an example of Christ’s victory in history before his return: 1 Corinthians 15.

In 1 Corinthians 15:20-28 Paul teaches not only that Christ currently sits upon the throne, but also that he rules with a confident view to subduing his enemies in history. (In this discussion I will employ the New International Version as my basic English translation due to its greater fidelity to several particulars of the Greek grammar in this passage.)

But Christ has indeed been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For since death came through a man, the resurrection of the dead comes also through a man. For as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive. But each in his own turn: Christ, the firstfruits; then, when he comes, those who belong to him. Then the end will come, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. For he “has put everything under his feet.” Now when it says that “everything” has been put under him, it is clear that this does not include God himself, who put everything under Christ. When he has done this, then the Son himself will be made subject to him who put everything under him, so that God may be all in all.

Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond

(ed. by Darrell Bock)

Presents three views on the millennium: progressive dispensationalist, amillennialist, and reconstructionist postmillennialist viewpoints. Includes separate responses to each view

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The End

In 1 Corinthians 15:20–22 Paul speaks of the resurrection order: Christ is resurrected as a first fruits promise of our resurrection. In verses 23–24 we read about the sequence of events involving the resurrection: “But each in his own turn: Christ the first fruits; then, when he comes, those who belong to him. Then the end will come.” We today are currently in the era awaiting Christ’s end-time coming, when all believers will arise in resurrection glory. When Christ comes this will be “the end”! Scripture is clear that the resurrection is a “general resurrection” of both the righteous and unrighteous (John 5:28–29; Acts 24:15), which will occur on the “last day” (John 6:39–40, 44, 54; 11:24; 12:48). Thus, according to Paul (and Jesus) no millennial age will follow. The resurrection of believers occurs on the “last day,” not 10071 years before the “last day.”

But notice what precedes the end. First Corinthians 15:24 says: “the end will come, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father.” Earth history ends “whenever” 2 Christ “hands over” the kingdom to the Father. In the Greek structure before us, his “handing over” (NIV) or “delivering up” (KJV) the kingdom occurs simultaneously with “the end.” Here the timing is contingent: “whenever” he delivers up the kingdom, then the end will come. In addition, he will deliver up his kingdom to the Father only “after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power.”

So then, the end of history is contingent: it will come whenever it may be that Christ delivers up the kingdom to his Father. But this will not occur until “after He has destroyed all dominion, authority and power” (see also: ESV). Consequently, the end will not occur, and Christ will not turn the kingdom over to the Father, until after he has abolished all opposition. Here again we see the gospel victory motif in the New Testament in a way co-ordinate with Old Testament covenantal and prophetic expectations.

Before the End

Notice further that 1 Corinthians 15:25 demands that “He must reign until He has put all His enemies under His feet.” Here the present infinitive for “reign” indicates an ongoing reign that exists as Paul writes. Christ is presently reigning, and has been so since his ascension. References elsewhere to Psalm 110 specifically mention his sitting at God’s right hand, which entails active ruling and reigning, not passive resignation or anxious waiting. As John informs us, Jesus is now “the ruler over the kings of the earth” and “has made us kings and priests to His God and Father, to Him be glory and dominion forever and ever” (Rev 1:5–6; cp. Rev 3:21).

Amillennialism v. Postmillennialism Debate

(DVD by Gentry and Gaffin)

Formal, public debate between Dr. Richard Gaffin (Westminster Theological Seminary)

and Kenneth Gentry at the Van Til Conference in Maryland.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Thus, in 1 Corinthians 11:25 Paul states that Christ must continue reigning as he puts his enemies under his feet. But to what point in time does his reign continue? The answer is identical to our previous conclusion: his reign from the right hand of God in heaven extends to the end of history. We must understand his rule as definitive, progressive, and consummative. That is, during his earthly ministry he awaits his resurrection in order to secure the definitive (legal) right to all rule, authority and power (Matt 28:18; Eph 1:19–22; Phil 2:9–11; 1 Pet 3:21–22). Now that he rules from heaven until he returns, his return is delayed until he progressively (actively, continually) puts “all His enemies under His feet” (Paul’s repeating the fact of his sure conquest before the end is significant). Then consummatively (finally and fully), he will subdue our “last enemy,” death, by means of the final resurrection at his coming.3 Thus, Church history begins with his legal victory at the cross-resurrection-ascension, continues progressively as he subdues all of his other enemies, and ends finally at the eschatological resurrection, which conquers the final enemy, death.

In 1 Corinthians 15:27 Christ clearly has the legal title to rule, for the Father “has put everything under His feet.” This expression (borrowed from Psa 8:6) corresponds with Christ’s declaring that “all authority has been given Me” (Matt 28:18). He has both the right to victory as well as the promise of victory. Psalm 110, especially as expounded by Paul in 1 Corinthians 15, shows that he will secure historical victory over all earthly opposition before his second advent — in time and on earth.

June 29, 2015

WILL THE SON OF MAN FIND FAITH?

PMT 2015-078 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-078 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

In Luke 18:8 Jesus makes a statement that seems to undermine any notion of the postmillennial hope. There we read:

“I tell you that He will avenge them speedily. Nevertheless, when the Son of Man comes, will He really find faith on the earth?”

Dispensationalists employ this verse with great confidence against postmillennialism. And we can certainly see why. Consider the following comments by dispensationalists.

Wayne House and Thomas Ice: “This is ‘an inferential question to which a negative answer is expected.’ So this passage is saying that at the second coming Christ will not find, literally, ‘the faith’ upon the earth.”

Hal Lindsey writes: “In the original Greek, this question assumes a negative answer. The original text has a definite article before faith, which in context means ‘this kind of faith.’”

Borland agrees: “The faith spoken of is probably the body of truth, or revealed doctrine, since the word is preceded by the definite article in the original. Improvement in the worldwide spiritual climate is not here predicted.”

Wiersbe follows suit: “The end times will not be days of great faith.” [1]

This verse is also brought out by amillennialists, such as R. B. Kuiper, Herman Hanko, Donald Bloesch, and Kim Riddlebarger, [2] as well as premillennialists such as Wayne Grudem. [3] Indeed, amillennialist D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones dogmatically asserts: “There is one verse, one statement, which, as far as I am concerned, is enough to put the postmillennial view right out. It is Luke 18:8.” [4] Bloesch declares that postmillennialism “flatly contradicts Jesus’ intimation” here in Luke 18:8. [5]

Christianity and the World Religions:

An Introduction to the World’s Major Faiths

By Derek CooperCooper examines the rival worldviews found in Hinduism,

Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism, Judaism, Islam, and irreligion.

He engages these worldviews from a Christian perspective.

See more study materials: www.KennethGentry.com

But things are not what they appear to be. So I would like to note several avenues of rebuttal. As postmillennialists, we may, in fact, be warmed and filled!

First, we must determine the focus of the question.

Some doubt exists regarding whether this question is even dealing with Christianity’s future existence as such. In the context, the Lord is dealing with the matter of fervent prayer. The definite article that Borland thinks must refer to “the body of truth, or revealed doctrine” seems rather to refer to the faith in prayer evidenced in the importune widow’s persistence: “Then He spoke a parable to them, that men always ought to pray and not lose heart” (Lk 18:1). Here Christ is asking if that sort of persistent prayer will continue after he is gone.

B. B. Warfield demonstrates that the reference to “the faith” has to do with the faith-trait under question in the parable: perseverance. He doubts the reference even touches on whether or not the Christian faith will be alive then, but rather: Will Christians still be persevering in the hope of the Lord’s vindicating their cause? As in Matthew 7:13–14, He was urging them to keep persevering. [6] This interpretation of the meaning of “the faith,” appears among non-premillennialists,[7] as well as premillennialists and even some dispensationalists. [8]

Second, we must determine the expectation in the question.

Even if it does refer to the Christian faith or the system of Christian truth, why is a negative prospect expected? As with the Matthew 7:13–14 passage, could not Christ be seeking to motivate his people, encouraging them to understand that the answer issues forth in an optimistic prospect? In another context was not Peter’s answer to such a query optimistic (Jn 6:67, 68)? Could it not be that the question is asked for the purpose not of speculation but of self-examination?

In point of fact, the question does not “assume” a negative answer at all. It is not a rhetorical question. The Funk-Blass-Debrunner Greek grammar notes that when an interrogative particle is used, as in Luke 18:8, “ou is employed to suggest an affirmative answer, me (meti) a negative reply” (p. 226 § 440). But neither of these particles occurs here. Thus, the implied answer to the question is “ambiguous” (p. 226), because the Greek word used here (ara) implies only “a tone of suspense or impatience in interrogation” (BAGD, 127).

Covenantal Theonomy

(by Ken Gentry)

A defense of theonomic ethics against a leading Reformed critic.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Third, we must determine the terminus in view in the question.

Apparently, Christ has in mind his imminent coming in judgment upon Israel, not his distant second advent to end history. Christ clearly speaks of a soon vindication of his people, who cry out to him: “I tell you that He will avenge them speedily” (Lk 18:8a; cp. Rev 1:1; 6:9–10). He is urging his disciples to endure in prayer through the troublesome times coming upon them, just as he does in Matthew 24:13, which speaks of the first century generation (Mt 24:34). In fact, the preceding context of Luke 18 speaks of Jerusalem’s destruction (Lk 17:22–37).

Fourth, we must determine the implication of millennial views regarding the question.

In the final analysis, no evangelical millennial view supposes that absolutely no faith will exist on the earth at the Lord’s return. Yet, to read the statements I quote above regarding Luke 18:8 and its supposedly expecting a negative answer, one would surmise that Christianity will be totally and absolutely dead at his return.

Thus, non-postmillennialists cannot successfully employ this passage against postmillennialism. Its standard is misinterpreted: The Lord’s teaching regarding fervent prayer is changed into a warning regarding Christianity’s future. Its grammar is misconstrued: The grammar indicating concern becomes an instrument of doubt. Its goal is radically altered: Rather than speaking of soon-coming events, it supposedly points to history’s distant end. Its final result is overstated (even if all the preceding points be dismissed): No critic of postmillennialism teaches that “the faith” will entirely and completely vanish from the earth at Christ’s Return.

There now. I feel better already!

Notes

1. House and Ice, Dominion Theology, 229. Lindsey, The Road to Holocaust, 48. Borland in Liberty Commentary on the New Testament, 160. Wiersbe, Bible Exposition Commentary, 2:249.

2. Kuiper, God-Centered Evangelism, 209. Hanko, “An Exegetical Refutation of Postmillennialism,” 16. Bloesch, Last Things, 57. Riddlebarger, Case for Amillennialism, 237.

3. Grudem, Systematic Theology, 1124.

4. Lloyd-Jones, The Church and the Last Things, 217.

5. Bloesch, Last Things, 103.

6. Warfield, “The Importune Widow and the Alleged Failure of Faith,” in Warfield, Selected Shorter Writings of Benjamin B. Warfield, 2:698–710. See also: Marshall, Luke, 676.

7. Hendriksen, Luke, 818. Green, Luke, 642–43. Evans, Luke, NIBC. Nolland, Luke, 870.

8. Alford, Luke, 614. Robertson, Word Pictures, 2:232. Bock, Luke 2:1455–56.

9. Funk, A Greek Grammar of the New Testament, 226 (§ 440).

June 26, 2015

THIS AGE / THE AGE TO COME

PMT 2015-077 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-077 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

An important eschatological issue involves the New Testament principle of “this age” and “the age to come.” Christ himself speaks of “this age” and another “age to come” (Mt 12:32; Mk 10:30; Lk 18:30; 20:34–35). The present age is sin-laden present in which we live. The “age to come” brings eternal life of the eternal order (Lk 18:30); it involves resurrection and will not include marrying (Lk 20:34–35). It is truly consummate and final.

From the linear perspective of the Old Testament, ancient Israel believes that the “age to come” will be the Messianic era that would fully arrive after their current age ends. Yet in the New Testament we learn that the “age to come” begins in principle with the first century coming of Christ. It overlaps with “this age” which begins in Christ. Thus, we are not only children of “this age” (present, sin-laden temporal history), but are also spiritually children of “the age to come” (the final, perfected eternal age). We have our feet in both worlds. Or as Geerhardus Vos put it: “The age to come was perceived to bear in its womb another age to come.”

Because of this principle, we already share in the benefits of “the age to come.” This is because the two ages are linked by Christ’s ruling in both, for he has a name “far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this age, but also in the one to come” (Eph 1:21). Therefore, we have already “tasted the good word of God and the powers of the age to come” (Heb 6:5), despite living in “this present evil age” (Gal 1:4).

Blame It on the Brain?

Sub-title: Distinguishing Chemical Imbalances, Brain Disorders, and Disobedience

by Edward T. Welch

Depression, Attention Deficit Disorder, Alcoholism, Homosexuality.

Research suggests that more and more behaviors are caused by brain function or dysfunction.

But is it ever legitimate to blame misbehavior on the brain?

How can I know whether my brain made me do it?

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

We already experience resurrection — spiritually (Jn 5:24–25; Ro 6:4; Eph 2:6; 1Jn 3:14), though we look forward to a physical resurrection beyond “this present time” (Ro 8:18–23). Indeed, we even now sit “with Him in heavenly places” so that “in the ages to come He might show the surpassing riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus” (Eph 2:6b–7). We already partake of the “new creation” (2Co 5:17; Gal 6:15), though the eternal new creation still awaits us (2Pe 3:13). The shaking of the earth and splitting of rocks at Christ’s death (Mt 27:50–51) signal “that Christ’s death was the beginning of the end of the old creation and the inauguration of a new creation” (G. K. Beale).

We already enjoy the “new birth” into that new world (Jn 3:3; 1Pe 1:1, 23), though we will experience the fulness of “the glory of the children of God” only in the future (Ro 8:19, 23). We already possess the Spirit, who is the one who in that future age will “give life to your mortal bodies” (Ro 8:11). We already have victory over Satan (Mt 12:29; Ro 16:20; Jas 4:7), though he is the “god of this age” (2Co 4:4). We do good works now so that we might store up treasure “for the future” (1Ti 6:17–19; cp. Ro 2:5–7).

Greatness of the Great Commission

(by Ken Gentry)

An insightful analysis of the full implications of the great commission.

Impacts postmillennialism as well as the whole Christian worldview.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The central principle uniting “this age” and “the age to come” is the resurrection. Gaffin well states: “The unity of the resurrection of Christ and the resurrection of believers is such that the latter consists of two episodes in the experience of the individual believer — one which is already past, already realized, and one which is future, yet to be realized,” so that our “resurrection is both already and not yet” (Richard Gaffin). Two worlds co-exist in us through the Holy Spirit (Geerhardus Vos). Thus, the “last days” are unique in involving a merger of “this age” and the “age to come” as an “already / not yet” phenomenon. Truly, “Christ’s life, and especially death and resurrection through the Spirit, launched the end-time new creation for God’s glory” (G. K. Beale).

June 24, 2015

LORD’S DAY OR DAY OF THE LORD? (3)

PMT 2015-076 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-076 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

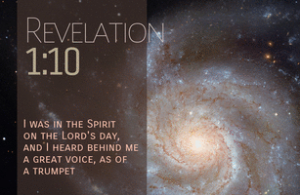

This is my final installment of a brief study on Rev 1:10. In this series I have been arguing that John’s “Lord’s day” is a reference to the eschatological “Day of the Lord” which crashes down on Jerusalem in AD 70. For context see the two preceding articles.

Third, John’s phrase is functionally equivalent to the more common one. Though Bauckham rejects this interpretation, according to Aune he “concludes that kuriakos is virtually synonymous with (tou) kuriou.” Thus, kuriakos can, in fact, be a synonym for the more common expression of the day of the Lord. Conceivably, John could simply be rephrasing the eschatological designate by using an adjective instead of noun in the genitive.

Thus, with Terry we must ask: “What remarkable difference is there between hemera kuriou and kuriake hemera?” The only other use of kuriakos in the NT refers to the “Lord’s supper” (kuriakon deipnon). This simply defines the sacramental supper as especially belonging to the Lord. This is exactly the significance of the judgmental “Lord’s day” in Rev for it signifies “the wrath of the Lamb” (6:16) and even “the great day of their wrath (6:17), i.e., God and the Lamb’s.

In the OT that judgment day especially belongs to God as a special day designated for his vengeance (Isa 13:9, 11–13; Eze 30:3, 8, 10, 12–16, 19; Zep 1:7–9, 14, 17). Later Origen (John 10:20) remarks on John 2:20 that “the whole house of Israel shall be raised up in the great Lord’s [day]” (Gk: pas oikos Israel en te megale kuriake egethesetai). This surely means the day of the Lord, and not Sunday.

The Christ of the Prophets (by O. Palmer Robertson)

Roberston examines the origins of prophetism, the prophets’ call,

and their proclamation and application of law and covenant.

A similar grammatical problem appears in Rev: this one regards the phrase “like to a son of man” in 1:13. Some commentators, such as Swete and Beasley-Murray, take the phrase “like to a son of man” in v 13 as not equivalent to Christ’s self-designation in the Gospels as “the Son of the Man.” This argument rests largely on the structural differences between the phrases: 1:13 leaves out the definite articles, which are found in the Gospels. (Surprisingly, Beasley-Murray contradicts himself by speaking of the same phrase in 14:14 as “the Son of man.”) Yet others, such as Charles and Hendriksen, identify the phrases. Charles even boldly states that the Apocalyptic statement here is “the exact equivalent” of that in the Gospels. Consequently, it would seem that identifying slightly different phrasing regarding the “Lord’s day” / “day of the Lord” would be tolerable here at 1:10, as well.

Fourth, in stating his Lord’s day experience he mentions the voice “as a trumpet (h s salpiggos] (1:10b). Osborne observes regarding the trumpet that “in almost every NT occurrence it has eschatological significance as a harbinger of the day of the Lord” (e.g., Mt 24:31; 1Co 15:52; 1Th 4:16). We should note the OT backdrop in Isa 27:13; Joel 2:1–2 (cp. Jer 4:5, 9; Hos 5:8; Zep 1:14–16; Zec 9:12–14). This association arises from the paradigmatic theophany at Sinai (Ex 19:16, 19–20) which shows the power of God’s coming and presence on earth. In Ex 19 “the Advent of Yahweh’s Presence at Sinai is the formative event of OT faith” (WBC) which is an “indescribable experience of the coming of Yahweh” (WBC). Hence, there we read of “the sounding of a trumpet to signal Yahweh’s arrival” (WBC); it “was, as it were, the herald’s call, announcing to the people the appearance of the Lord” (Keil and Delitzsch). Thus, later “day of the Lord” references pick up this trumpet sound; and in 1:10 John associates the trumpet with his “Lord’s day.”

Fifth, we discover important parallels between John’s experience in 1:10 and an identical one in 4:2 that strengthens the day of the Lord view. In both experiences John states egenomen en pneumati (“I became in Spirit”), hears a trumpet (1:10; 4:1), sees a member of the Godhead (1:12–18; 4:2–11), and in both contexts learns that God is the one “who was and who is and who is to come” (1:8; 4:8). Then in 1:19 he is directed to write about the things “which shall take place after these things,” while in 4:1 the trumpet voice informs him that “I will show you what must take place after these things.” Now whereas John becomes in the Spirit on the “Lord’s day” (i.e., “the day of the Lord”) in 1:10, in the vision following his transport into heaven at 4:1–2 he sees the slain Lamb (5:6) who takes the seven-sealed scroll (5:7) and opens it (6:1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 12) culminating in “the great day of their wrath” (6:17), i.e., the wrath of “Him who sits on the throne, and the from the wrath of the Lamb” (6:16). Both “in Spirit” visions mention the day of the Lord — if we interpret the phrase thus in 1:10.

He Shall Have Dominion

(paperback by Ken Gentry)

A classic, thorough explanation and defense of postmillennialism (600 pages)

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Sixth, it is highly unlikely that John received all of the visions in Rev on one day, Sunday. There are too many and they are too vigorous. Again, attached to his statement is the command to write what he sees in a book (1:10b), which is the book of Rev — the whole book of Rev (1:2). In response to this command he not only records the immediately following vision, but the seven letters (2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 12, 14), and other visions (10:4; 14:13; 19:9; 21:5). In fact, the command in 1:19 clearly covers the entire work, not just this vision.

Thus, strong evidence supports the eschatological “day of the Lord” interpretation in 1:10. Of course, as we know from the OT there are many “day” of the Lord judgments, each of which is eschatological in orientation (i.e., they reflect the final day of the Lord that concludes history). For instance, in Isa 13 we see OT Babylon (13:1, 19) being threatened by a “day of the Lord” (13:6, 9, 13). This day comes about by the hands of the Medes (13:17) as they devour by the sword (13:15). This is not referring to the final-final eschatological day of the Lord. John’s day of the Lord also is not final, focusing instead upon the AD 70 judgment against the first Jews and their temple.

Righteous Writing Correspondence Course

This course covers principles for reading a book, using the library,

determining a topie, formulating a thesis, outline, researching, library use,

writing clearly and effectively, getting published, marketing, and more!

June 22, 2015

LORD’S DAY OR DAY OF THE LORD? (2)

PMT 2014-074 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2014-074 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

I am continuing a presentation and defense of the view that John’s “Lord’s day” in Rev 1:10 is referring to “the Day of the Lord.” If this is so, it fits perfectly with the redemptive-historical preterist understanding of Revelation as a drama presenting Christ’s judgment-coming against Jerusalem and the temple in AD 70.

I will pick up where I left off in the last article. There I presented and briefly rebutted the argument for Rev 1:10 pointing to the Lord’s Day (the weekly day of worship). Now we are ready to look at the positive evidence for it picturing the Day of the Lord, i.e., AD 70.

So then, what evidence supports te kuriake hemera (“the Lord’s day”) as signifying an eschatological “day of the Lord”? I will present six arguments supporting this view.

First, the tone of this judgment-oriented book well suits the concept. In both the OT and NT the day of the Lord is a day of judgment, wrath, destruction, and doom (Isa 13:6, 9; Eze 30:3; Joel 1:15; 2:1; Am 5:18–20; Zep 1:14; Mal 4:5). It may even be called “the day of the wrath of the Lord” (Eze 7:19). Thus, it is appropriate that in his opening vision we hear of this dreaded day by way of anticipation. Indeed, attached to this statement regarding “the Lord’s day” is the trumpet voice commanding John to “write in a book what you see” (1:10b–11), which includes “all that he saw” (1:2). This means that the whole of Rev is impacted by this experience, not just the one vision following (1:12–20). And the remainder of Rev certainly presents numerous eschatological judgments.

Charismatic Gift of Prophecy

(by Ken Gentry)

A rebuttal to charismatic arguments for the gift of prophecy continuing in the church today.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Second, in fact, the day of the Lord expressly appears in Rev. In 6:17 terrified men cower before the one who sits on the throne and before the Lamb, crying out: “the great day of their wrath has come, and who is able to stand?”(6:17). (This fear of standing before the Lord also fits the eschatological day; cf. Eze 13:5; Joel 2:11; Mal 3:2). In 16:14 demons gather the world’s kings “for the war of the great day of God.” Commentators agree that these two passages speak of that eschatological day of the Lord (e.g., Beale; Smalley Osborne).

Interestingly, neither of these obvious references to the day of the Lord uses the common phraseology, hemera kuriou (see: Isa 13:6, 9; Eze 13:5; 30:3; Joel 1:15; 2:1, 31; Am 5:18; Ob 1:15; Zep 1:14; Mal 4:5; Ac 2:20; 1Th 5:2; 2Pe 3:10; cp. hemera tou kuriou, Am 5:20; Zep 1:7; 1Co 5:5; 2Th 2:2). So why may John not use different terminology in 1:10?

In fact, in Scripture the “day of the Lord” appears under a wide variety of expressions other than this leading phrasing. It is called: “the day of His burning anger” (Isa 13:13; cp. Lam 2:1; Zep 2:2, 3), “a day of panic” (Isa 22:5), “that day” (Isa 22:25; 24:21; 27:1; Jer 4:9; 30:8; Hos 2:21; Am 8:9; Ob 8; Mic 5:10; Zec 14:13), “a day of vengeance” (Isa 34:8; 61:2; Jer 46:10), “the day that is coming” (Jer 47:4), “the day of the wrath of the Lord” (Eze 7:19), “the day” (Eze 30:2, 3), “a unique day” (Zec 14:7), “the great and terrible day of the Lord” (Mal 4:5), and so forth.

Even the NT itself refers to it by different expressions, sometimes in the statements or writings by the same person: “his day” (Lk 17:24), “the day” (Lk 17:30; Ro 13:12), “that day” (Lk 10:12; 17:31; 21:34), “the great and glorious day of the Lord” (Ac 2:20), “the day of wrath and revelation” (Ro 2:5), “the day of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1Co 1:8), “the day of our Lord Jesus” (2Co 1:14), “the day of Jesus Christ” (Php 1:6), “the day of Christ” (Php 1:10), “the great day” (Jude 6), and so forth.

In Ac 2 Peter quotes Joel 2:31, applying “the day of the Lord” (hemeran kuriou ten megalen) in terms perfectly compatible with the fuller expressions in Rev. Peter’s “day of the Lord” upon Jerusalem points to Rev’s day: “I will grant wonders in the sky above, and signs on the earth beneath, blood, and fire, and vapor of smoke. The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood, before the great and glorious day of the lord shall come” (Ac 2:19–20). Rev bursts with such destruction imagery: “blood,” “fire,” and “smoke,” as well as a darkened sun (6:12; 8:12; 9:2), and a bloody moon (6:12). Interestingly, Peter points to the tongues-speaking (Ac 2:16, cp. vv 2–15) of Pentecost as a sign of the approaching “day of the Lord” (Ac 2:16–17, 20–21). As such, tongues were a sign to non-believing Jews regarding the day of the Lord against them in the first century (cp. 1Co 14:22; cp. Dt 28:49; Isa. 28:11; 33:19; Jer. 5:15).

Tongues-Speaking: Meaning, Purpose, and Cessation

(Book) by Ken Gentry

A careful study of the biblical material defining the gift of tongues.

Shows they were known languages that served to endorse the apostolic witness

and point to the coming destruction of Jerusalem, after which they ceased.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

June 19, 2015

LORD’S DAY OR DAY OF THE LORD? (1)

PM T 2014-074 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

T 2014-074 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

I recently received an inquiry regarding my preterist understanding of Rev 1:10. This verse reads: “I was in the Spirit on the Lord’s day, and I heard behind me a loud voice like the sound of a trumpet.” The writer was wanting a little more argument for my view. I hold that John is speaking of “the Day of the Lord,” rather than “the Lord’s Day” (Sunday). In this and the following posts, I will engage the question. Let’s get started.

John tells us here that he was in the Spirit “on the Lord’s day” (1:10a). Most commentators see the Greek phrase kuriake hemera (“Lord’s day”) as referring to when John received his vision, i.e., on the first day of the week, the Christian day of worship. As the argument goes, quite early in Christian history the word kuriake (“Lord’s”) was used to refer to Sunday (e.g., Did. 14:1; Ignatius, Mag. 9:1; Gosp. Pet. 12:50; Clem. Alex., Strom. 17:12). And we see it with hemera (“day”) in Origen (Cel. 8:22) and Dionysius (cited in Eusebius, Eccl. Hist. 4:23:8).

But not all agree that this was John’s intent. Some commentators (a minority) hold that it refers to an eschatological day of the Lord. Though disagreeing, EDNT (2:331) notes that it is “possibly reminiscent of the OT ‘day of the Lord’ (Joel 2:31 LXX).” Those suggesting that the phrase indicates an eschatological “day of the Lord” include: Milton Terry, F. J. A. Hort, William Milligan, John F. Walvoord, Samuele Bacchiocchi, and Ranko Stefanovic. Others holding this position include: Johann J. Wetstein, C. F. J. Zullig, A. G. Maitland, Vander Honert G. B. Winer, Adolf Deissman, J. B. Lightfoot, E. W. Bullinger, and Walter Scott. Though G. K. Beale calls “attractive,” he ultimately rejects it.

Blessed Is He Who Reads: A Primer on the Book of Revelation

By Larry E. Ball

A basic survey of Revelation from the preterist perspective.

It sees John as focusing on the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in AD 70.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

The main arguments against kuriake hemera referring to the “day of the Lord” and therefore supporting its application to Sunday (or sometimes: Easter) are basically three: (1) Lexically, in Scripture the day of the Lord is never referred to by the adjective kuriake. (2) Contextually, this statement introduces a vision of the Son of Man walking among the churches, which does not suggest a judgmental day of the Lord. (3) Historically, the term kuriake absolutely and with the noun hemeras are applied later by the Church Fathers to the Christian day of worship.

Nevertheless, I believe John is referring to the “day of the Lord.” I will briefly respond to the arguments brought against this view first, then I will cite the positive evidence supporting it.

First, regarding the fact that Scripture never refers to the day of the Lord by using kuriake, I would point out that this argument cuts both ways: neither does it use the term for the Christian day of worship. In the NT the day of worship is called simply “the first day of the week” (Ac 20:7; 1Co 16:2), never “the Lord’s day.” Even John in his Gospel refers to the day of Jesus’ resurrection (which becomes for that reason, the day of Christian worship) as “the first day of the week” (Jn 20:1, 19).

Second, though the reference introduces the vision of Christ walking among the candlesticks, the day of the Lord interpretation is contextually suitable for several reasons: (1) It follows just three verses after a statement regarding Christ’s judgment-coming on the clouds (1:7), which is most definitely an image of the day of the Lord (cf. Eze 30:3; Joel 2:2; Zep 1:15).

(2) In 1:8 God declares that he is the one “who is and who was and who is to come.” Smalley recognizes a relationship between the erchetai in 1:7 and erchomenos in 1:8, observing that “the advent theme of verse 7, centred in the returning Christ, is picked up here once again, and set within the total context of the judgement and salvation brought by the living Godhead.”

Bringing Heaven Down to Earth

(by Nathan Bierma)

A Reformed study of heaven. By taking a new look at the biblical picture of heaven,

Nathan Bierma shows readers how heaven can be a relevant, meaningful,

inspiring engine of Christian faith and kingdom service.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

(3) In the immediately preceding verse John mentions the “tribulation” which the churches are already enduring and which call for “patience” (1:9). Thus, here in his introductory vision he is encouraging their patience by informing them that though the divine judgments in Rev will “soon take place” (1:1) because “the time is near” (1:3), Christ is among them as their protector as well as their judge. Therefore, they must weather the coming storms by means of his holy presence (2:2–5; 14–16, 19–25; 3:2–4, 11, 15–16, 19) and they can weather the storms because of his powerful presence (2:10, 26–28; 3:5, 8–10, 20–21).

(4) This vision of Christ expressly relates to Christ’s AD 70 judgment-coming for John takes aspects of the vision and applies them to the churches who also are enduring the wrath of “the Jews” (2:9; 3:9) who were the ones who “pierced” him (1:7). The Christ of the vision expressly informs one church (3:7 cp. 1:18b; cf. Beale 283) that he will make the Jews “come and bow down at your feet, and to know that I have loved you” (3:9b).

Third, though the term kuriake was later applied to the Christian day of worship, it never is in Scripture. Almost certainly this language was picked up by the Church fathers not only as appropriate for that day, but as assumed to be referring to it. If we could find this language in the NT as clearly applying to Sunday, this would provide insurmountable evidence. But we do not — and “there is no certainty that the name was generally received from the first” (Hort). Furthermore, Bacchiocchi summarizes an extensive argument showing that one of the leading “evidences” for this view not only does not even qualify the noun hemera (day) when it reads kata kuriaken de kuriou, but it may actually be speaking not of “the time but the manner of the celebration of the Lord’s Supper.”

To be continued.

June 17, 2015

WHAT VERSION DID JOHN USE?

PMT 2015-073 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-073 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

Revelation is the most Old Testament oriented book in the New Testament. It exceeds both Matthew and Hebrews in its alluding to the Old Testament. But an intriguing question arises regarding this extremely OT-influenced work: What is John’s specific OT version? We know he did not use the King James Version, despite many KJV-Only enthusiasts.

J. B. Lightfoot states that John’s allusions “are so free that we cannot say whether they were taken from the Hebrew or the Greek.” R. H. Charles disagrees, expressing his position dogmatically: “John translated directly from the O.T. text. He did not quote from the Greek Version.” Steve Moyise surveys the following noted Hebrew-source advocates in addition to Charles A. Vanhoye, C. G. Ozanne, A. T. Hanson, J. Fekkes, F. D. Mazzaferri, J. P. M. Sweet, and L. P. Trudinger. I would also add S. Thompson and B. Witherington.

I will cite just two samples of the Hebrew text influence on John over against the LXX (the Septuagint, the Greek version of the OT). At 1:7 John alludes to Zec 12:10 and clearly reflects the Hebrew rendering which has the Hebrew daqarû (“pierced”) rather than the LXX’s katorchesanto (“crushed”). At 3:7 he alludes to Isa 22:22 choosing the Hebrew wording maptëh (“key” of David) over against the LXX doxan (“glory” of David).

Four Views on the Book of Revelation

(ed. by Marvin Pate)

Helpful presentation of four approaches to Revelation.

Ken Gentry writes the chapter on the preterist approach to Revelation.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Not all agree, however. H. B. Swete challenges Charles’ claim that John works from the Hebrew; instead he argues that “the familiar phraseology of the LXX. meets us everywhere.” A. T. Robertson concurs, noting that in Rev we experience “the flavour of the LXX whose words are interwoven in the text at every turn.”

To support his position, Swete provides thirteen pages of references demonstrating from 257 Rev phrases (my count) that the LXX was John’s preferred OT source. We may see one clear example of LXX flavoring in Rev 20:9 which reads: katebe ek tou ouranou kai katephagen autous. This matches closely with 2Ki 1:10 which has: kateb pur ek tou ouranou kai katephagen auton. Furthermore, we see a number of instances of John’s adopting peculiar LXX readings over against the Hebrew. For example, in Rev 11:18 John alludes to Ps 99:1 [98:1] and prefers the LXX’s “angry”(orgizesthesan) rather than the Hebrew text’s “tremble” (yirìrgìzû). In Rev 2:27; 12:5; and 19:15 his allusions to Ps 2:9 prefer the LXX’s “rule” (poimaneis) over the Hebrew’s “crush” (raa ). A minority of scholars agree that John prefers the LXX, including Laughlin, Rowley, Schmidt, and Beale.

Moyise rejects any exclusive use of either the Hebrew or Greek versions of the OT: “Attempts by Swete (Greek) and Ozanne (Hebrew) to show an exclusive use of one or other require extensive special pleading and should be rejected. . . . On the available evidence, therefore, I conclude that John knew and used both Greek and Semitic sources and that the consensus view, that John preferred Semitic texts, remains unproven.” He points out that the problem facing a LXX position are offset by considering the similar problem when working on the assumption of the Hebrew perspective. He concludes that “the evidence suggests that John knew and used both Greek and Hebrew texts.” Paul Penley concurs.

Getting the Message

(by Daniel Doriani)

Presents solid principles and clear examples of biblical interpretation.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

While arguing that John prefers the Hebrew text, D. Mathewson states that “although it appears that there are times when John drew on the LXX or an Aramaic version, there is general agreement that the Hebrew Bible constitutes the primary quarry from which John drew his material.” Even Beale, who sees the LXX as John’ preferred version, acknowledges that “John draws from both Semitic and Greek biblical sources and often modifies both.”

That John draws from both the Hebrew and Greek versions of the OT seems preferable in light of all the qualifications that must be made when preferring one version over the other.

June 15, 2015

JOHN’S USE OF EZEKIEL

PMT 2015-072 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-072 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

Though John saw his visions, we do not. Consequently, he has to relate them to us through verbal communication. And John is so absorbed with the Old Testament Scriptures that he presents his visions in Old Testament language. John intentionally takes up the prophetic mantle, even mimicking the Old Testament grammar, as well as alluding to their writings.

H. Charles observes that “our author makes most use of the prophetical books.” Colin Hemer agrees: “the influence of the prophets on John’s mind is especially strong.” More precisely, H. B. Swete argues that John’s favorite OT books are in the following order: Daniel, Isaiah, Ezekiel, and the Psalms. I would qualify this by noting regarding the Psalms that John is especially interested in the prophetic and Messianic psalms. Charles Hill adds Zechariah to the list. G. K. Beale and D. A . Carson disagree with Swete’s ranking, pointing out that “Ezekiel exerts greater influence in Revelation than does Daniel.”

Interestingly, Steve Moyise argues that not only is Rev “the only New Testament book that significantly alludes to the book of Ezekiel,” but “over half of the allusions to Ezekiel in the NT come from the book of Revelation.” Many scholars agree with Ezekiel’s strong influence. F. D. Mazzaferri notes that “by a very long measure, [John’s] favourite exemplar is Ezekiel.” P. Prigent agrees: “it is patently obvious that the book of Revelation and Ezekiel are very closely linked.” D. Mathewson summarizes current scholarly conclusions that “there is little dispute that Ezekiel has exerted a formidable influence on the book of Revelation” and that there is even “substantial agreement on the major sections of influence.”

Book of Revelation Made Easy

(by Ken Gentry)

Helpful introduction to Revelation presenting keys for interpreting.

Also provides studies of basic issues in Revelation’s story-line.|

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

A sampling of the OT influence from Ezekiel is quite remarkable. The following few, clear samples illustrate how Ezekiel impacts Rev at significant points:

(1) The all-important throne-room vision of God in Rev 4:1–11 draws from Eze 1. (2) In 5:10 the double-sided scroll in God’s hand on the throne that initiates the divine judgments strongly reflects Eze 3:3. In addition, note: (3) the marking of the foreheads (Eze 9:4; Rev 7:3); (4) the coals thrown to the earth from heaven (Eze 10:2; Rev 8:5); (5) the four judgments related to the fourth seal (Eze 14:21; Rev 6:8); (6) Gog and Magog (Eze 38–39; Rev 20:7–10); (7) the birds flocking to their prey as symbols of divine judgment (Eze 39:17ff; Rev 19:17ff); (8) the glorified Jerusalem (Eze. 40–47; Rev 21); and more. According to Beale and Carson: M. D. Goulder has argued that broad portions of Ezekiel have been the dominant influence on at least twelve major sections of Revelation (Rev. 4; 5; 6:1–8; 6:12—7:1; 7:2–8; 8:1–5; 10:1–7; 14:6–12; 17:1–6; 18:9–24; 20:7–10; 21:22).

Carrington goes so far as to declare that “the Revelation is a Christian rewriting of Ezekiel. Its fundamental structure is the same. Its interpretation depends upon Ezekiel.” Goulder states even further that “these uses of Ezekiel are a dominant influence on the structure of Revelation, since they are placed to a marked extent in the same order as they occur in Ezekiel itself.” J. M. Vogelgesang agrees that “the order of Ezekelian passages used in Revelation approximate the order of Ezekiel itself.” I. Boxall concurs: “Ezekiel has been a key text for John throughout, often providing the sequential structure.”

The Climax of the Book of Revelation (Rev 19-22)

Six lectures on six DVDs that introduce Revelation as a whole,

then focuses on its glorious conclusion.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

Boxall provides us with a helpful table demonstrating Ezekiel’s influence on Rev:

Rev 1 = Eze 1

Rev 4 = Eze 1

Rev 5 = Eze 2

Rev 6 = Eze 5–7

Rev 7:1–2 = Eze 7:2–3

Rev 7–8 = Eze 9–10

Rev 10 = Eze 2–3 (cp. Rev 5)

Rev 10–13 = Eze 11–14 (echoes)

Rev 11:1–2 = Eze 40

Rev 13:11–18 = Eze 14

Rev 17 = Eze 16, 23

Rev 18 = Eze 26–28

Rev 19:11–21 = Eze 29, 32 (39)

Rev 20:1–3 = Eze 29, 32

Rev 20:4–6 = Eze 37

Rev 20:7–10 = Eze 38:1–39:20

Rev 10:11–15 = Eze 39:21–29

Rev 21–22 = Eze 40–48

Thus, John’s fundamental backdrop is the OT prophetic witness, and particularly that witness as influenced by Ezekiel.

June 12, 2015

REVELATION’S EARLY DATE (2)

PMT 2015-070 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-070 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

This is the second in a two-part series briefly presenting the evidence for the early dating of Revelation. That is, for a date prior to the destruction of the Jewish temple in AD 70. In the preceding article I presented the evidence from Revelation 11 regarding the presence of the temple in Revelation. In this article I will pose two more lines of argument.

The Seven Kings in Revelation 17

In Revelation 17:1-6 a vision of a seven-headed beast is recorded. In this vision we discover strong evidence that Revelation was written before the death of Nero, which occurred on June 8, A.D. 68.

John wrote to be understood. The first of seven benedictions occurs in his introduction: “Blessed is he that reads, and they that hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written therein” (Rev. 1:3). And just after the vision itself is given in Revelation 17:1-6, an interpretive angel appears for the express purpose of explaining the vision: “And the angel said unto me, Wherefore didst thou marvel? I will tell thee the mystery of the woman, and of the beast that carrieth her, which hath the seven heads and ten horns” (Rev 17:7). Then in verses 9 and 10 this angel explains the vision: “Here is the mind which hath wisdom. The seven heads are seven mountains, on which the woman sitteth. And there are seven kings: five are fallen, and one is, and the other is not yet come; and when he cometh, he must continue a short space.”

Most evangelical scholars recognize that the seven mountains represent the famed seven hills of Rome. The recipients of Revelation lived under the rule of Rome, which was universally distinguished by its seven hills. How could the recipients, living in the seven historical churches of Asia Minor and under Roman imperial rule, understand anything else but this geographical feature?

Theological Debates Today

(5 mp3 messages by Ken Gentry)

Conference lectures on contemporary theological issues:

1. The Great Tribulation; 2. The Book of Revelation;

3. Hyperpreterism; 4. Paedocommunion; 5. God’s Law

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

But there is an additional difficulty involved. The seven heads have a two-fold referent. We learn also that the seven heads represent a political situation in which five kings have fallen, the sixth is, and the seventh is yet to come and will remain but a short while. It is surely no accident that Nero was the sixth emperor of Rome, who reigned after the deaths of his five predecessors and before the brief rule of the seventh emperor.

Flavius Josephus, the Jewish contemporary of John, clearly points out that Julius Caesar was the first emperor of Rome and that he was followed in succession by Augustus, Tiberius, Caius, Claudius, and Nero (Antiquities 18; 19). We discover this enumeration also in other near contemporaries of John: 4 Ezra 11 and 12; Sibylline Oracles, books 5 and 8; Barnabas, Epistle 4; Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars; and Dio Cassius’ Roman History 5.

The text of Revelation says of the seven kings “five have fallen.” The first five emperors are dead, when John writes. But the verse goes on to say “one is.” That is, the sixth one is then reigning even as John wrote. That would be Nero Caesar, who assumed imperial power upon the death of Claudius in October, A.D. 54, and remained emperor until June, A.D. 68.

John continues: “The other is not yet come; and when he comes, he must continue a short space.” When the Roman Civil Wars broke out in rebellion against him, Nero committed suicide on June 8, A.D. 68. The seventh king was “not yet come.” That would be Galba, who assumed power in June, A.D. 68. But he was only to continue a “short space.” His reign lasted but six months, until January 15, A.D. 69.

Thus, we see that while John wrote, Nero was still alive and Galba was looming in the near future. Revelation could not have been written after June, A.D. 68, according to the internal political evidence.

The Jews in Revelation

The final evidence from Revelation’s self-witness that I will consider is the relationship of the Jew to Christianity in Revelation. And although there are several aspects of this evidence, we will just briefly introduce it. Two important passages and their implications may be referred to illustratively.

Revelation, God, and Man

(24 Gentry Lectures in mp3 on USB)

Formal Christ College course on the doctrines of revelation, God, and man.

Opens with introduction to the study of systematic theology.

Excellent material for personal study or group Bible study.

Strongly Reformed and covenantal in orientation.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

First, when John writes Revelation, Christians are tensely mingled with the Jews. Christianity is presenting herself as the true Israel and Christians the real Jews (cp. Gal. Gal. 3:6-9, 29; Phil. 3:3; 1 Pet. 2:9). In Revelation 2:9 we read of Jesus’ word to one of his churches of the day: “I know your tribulation and your poverty (but you are rich), and the blasphemy by those who say they are Jews and are not, but are a synagogue of Satan.”

Who but a Jew would call himself a Jew? But in the early formative history of Christianity, believers are everywhere in the New Testament presented as “Abraham’s seed,” “the circumcision,” “the Israel of God,” the “true Jew,” etc. We must remember that even Paul, the apostle to the Gentiles, took Jewish vows and had Timothy circumcised. But after the destruction of the Temple (A.D. 70) there was no tendency to inter-mingling. In fact, the famed Jewish rabbi, Gamaliel II, put a curse on Christians in the daily benediction, which virtually forbad social inter-mingling.

In Revelation the Jews are represented as emptily calling themselves “Jews.” They are not true Jews in the fundamental, spiritual sense, which was Paul’s argument in Romans 2. This would suggest a date prior to the final separation of Judaism and Christianity. Christianity was a protected religion under Rome’s religio licita legislation, as long as it was considered a sect of Judaism. The legal separation of Christianity from Judaism was in its earliest stages, beginning with the Neronic persecution in late A.D. 64. It was finalized both legally and culturally with the Temple’s destruction, as virtually all historical and New Testament scholars agree. Interestingly, in the A.D. 80s the Christian writer Barnabas makes a radical “us/them” division between Israel and the Church (Epistle 13:1).

Second, at the time John writes, things are in the initial stages of a fundamental change. Revelation 3:9 reads: “Behold, I will cause those of the synagogue of Satan, who say that they are Jews, and are not, but lie — behold, I will make them to come and bow down at your feet, and to know that I have loved you.”

John points to the approaching humiliation of the Jews, noting that God will vindicate his Church against them. In effect, He would make the Jews to lie down at the Christian’s feet. This can have reference to nothing other than the destruction of Israel and the Temple, which was prophesied by Christ. After that horrible event Christians began making reference to the Temple’s destruction as an apologetic and vindication of Christianity. Ignatius (A.D. 107) is a classic example of this in his Magnesians 10. There are scores of such references in such writers as Melito, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Lactantius, and others.

There are other arguments regarding the Jewish character of Revelation, such as its grammar, its reference to the twelve tribes, allusions to the priestly system, temple worship, and so forth. The point seems clear enough: When John writes Revelation, Christianity is not divorced from Israel. After A.D. 70 such would not be the case. This is strong socio-cultural evidence for a pre-A.D. 70 composition.

Righteous Writing Correspondence Course

This course covers principles for reading a book, using the library,

determining a topie, formulating a thesis, outline, researching, library use,

writing clearly and effectively, getting published, marketing, and more!

June 10, 2015

REVELATION’S EARLY DATE (1)

PMT 2015-070 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

PMT 2015-070 by Kenneth L. Gentry, Jr.

In this two-article series, I will briefly present the basic evidence for Revelation’s pre-AD 70 composition. A preteristic understanding of Revelation is strongly (though not absolutely) linked with its early dating. And the dating of Revelation is not a theoretical assumption, but is based on exegetical evidence.

There are two basic positions on the dating of Revelation, although each has several slight variations. The current majority position is the late-date view. This view holds that the Apostle John wrote Revelation toward the close of the reign of Domitian Caesar — about A.D. 95 or 96. The minority view-point today is the early-date position. Early-date advocates hold that Revelation was written by John prior to the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in A.D. 70.

I hold that Revelation was produced prior to the death of Nero in June, A.D. 68, and even before the formal engagement of the Jewish War by Vespasian in Spring, A.D. 67. My position is that Revelation was written in A.D. 65 or 66. This would be after the outbreak of the Neronic persecution in November, 64, and before the engagement of Vespasian’s forces in Spring of 67.

Though the late-date view is the majority position today, this has not always been the case. In fact, it is the opposite of what prevailed among leading biblical scholars a little over seventy-five years ago. Late-date advocate William Milligan conceded in 1893 that “recent scholarship has, with little exception, decided in favour of the earlier and not the later date.” Two-decades later in 1910 early-date advocate Philip Schaff could still confirm Milligan’s report: “The early date is now accepted by perhaps the majority of scholars.”

Before Jerusalem Fell

by Ken Gentry

Doctoral dissertation defending a pre-AD 70 date for Revelation’s writing.

Thoroughly covers internal evidence from Revelation, external evidence from history,

and objections to the early date by scholars.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

In the 1800s and early 1900s the early-date position was held by such worthies as Moses Stuart, Friederich Düsterdieck, B. F. Westcott, F. J. A. Hort, Joseph B. Lightfoot, F. W. Farrar, Alfred Edersheim, Philip Schaff, Milton Terry, Augustus Strong, and others. Though in eclipse presently, the early-date view has not totally faded away, however. More recent advocates of the early-date include Albert A. Bell, F. F. Bruce, Rudolf Bultmann, C. C. Torrey, J. A. T. Robinson, J. A. Fitzmeyer, J. M. Ford, C. F. D. Moule, Cornelius Vanderwaal, and others.

But rather than committing an ad verecundiam fallacy, let us move beyond any appeal to authority and consider very briefly the argument for the early date of Revelation. Due to time constraints, I will succinctly engage only three of the internal indicators of composition date. The internal evidence should hold priority for the evangelical Christian in that it is evidence from Revelation’s self-witness. I will only summarily allude to the arguments from tradition before concluding this matter. Generally it is the practice of late-date advocates to begin with the evidence from tradition, while early-date advocates start with the evidence from self-witness.

The Temple in Revelation 11

In Revelation 11:1, 2 we read:

And there was given me a reed like unto a rod: and the angel stood, saying, Rise, and measure the temple of God, and the altar, and them that worship therein. But the court which is without the temple leave out, and measure it not; for it is given unto the Gentiles: and the holy city shall they tread under foot forty and two months.

Here we find a Temple standing in a city called “the holy city.” Surely John, a Christian Jew, has in mind historical Jerusalem when he speaks of “the holy city.” This seems necessary in that John is writing scripture and Jerusalem is frequently called the “holy city” in the Bible. For example: Isaiah 48:2; 52:1; Daniel 9:24; Nehemiah 11:1-18; Matthew 4:5; 27:53. In addition, verse 8 informs us that this is the city where “also our Lord was crucified.” This was historical Jerusalem, according to the clear testimony of Scripture (Luke 9:22; 13:32; 17:11; 19:28). Interestingly, historical Jerusalem is never mentioned by name in Revelation. This may be due to the name “Jerusalem” meaning “city of peace.” In Revelation the meanings of specific names are important to the dramatic imagery. And so it would be inappropriate to apply the name “Jerusalem” to the city upon which woe and destruction are wreaked.

Now what Temple stood in Jerusalem? Obviously the Jewish Temple ordained of God, wherein the Jewish sacrifices were offered. In the first century it was known as Herod’s Temple. This reference to the Temple must be that historical structure for four reasons:

Great Tribulation: Past or Future?

(Thomas Ice v. Ken Gentry)

Debate book on the nature and timing of the great tribulation.

Both sides thoroughly cover the evidence they deem necessary,

then interact with each other.

See more study materials at: www.KennethGentry.com

(1) It was located in Jerusalem, as the text clearly states in verse 8. This can only refer to the Herodian Temple, which appears over and over again in the New Testament record. It was the very Temple which was even the subject of one of Christ’s longer prophetic discourses (Matt. 23:37-24:2ff).

(2) Revelation 11:1, 2, written by the beloved disciple and hearer of Christ, seems clearly to draw upon Jesus’ statement from the Olivet Discourse. In Luke 21:5-7, the disciples specifically point to the Herodian Temple to inquire of its future; in Revelation 11:1 John specifically speaks of the Temple of God. In Luke 21:6 Jesus tells his disciples that the Temple will soon be destroyed stone by stone. A comparison of Luke 21:24 and Revelation 11:2 strongly suggests that the source of Revelation’s statement is Christ’s word in Luke 21.

Luke 21:24b: “Jerusalem will be trampled underfoot by the Gentiles until the times of the Gentiles be fulfilled.”

Revelation 11:2b: “it is given unto the Gentiles: and the holy city shall they tread under foot for forty and two months.”

The two passages speak of the same unique event and even employ virtually identical terms.

(3) According to Revelation 11:2 Jerusalem and the Temple were to be under assault for a period of forty-two months. We know from history that the Jewish War with Rome was formally engaged in Spring, A.D. 67, and was won with the collapse of the Temple in August, A.D. 70. This is a period of forty-two months, which fits the precise measurement of John’s prophecy. Thus, John’s prophecy antedates the outbreak of the Jewish War.

(4) After the reference to the destruction of the “temple of God” in the “holy city,” John later speaks of a “new Jerusalem” coming down out of heaven, which is called the “holy city” (Rev. 21:2) and which does not need a temple (Rev. 21:22). This new Jerusalem is apparently meant to supplant the old Jerusalem with its temple system. The old order Temple was destroyed in August, A.D. 70.

Thus, while John wrote, the Temple was still standing, awaiting its approaching doom. If John wrote this twenty-five years after the Temple’s fall it would be terribly anachronous. The reference to the Temple is hard architectural evidence that gets us back into an era pre-A.D. 70.

Kenneth L. Gentry Jr.'s Blog

- Kenneth L. Gentry Jr.'s profile

- 85 followers