Gary Gauthier's Blog, page 4

April 6, 2013

Confused and Obscure v. Clear and Distinct

Large cat can mean Tabby, lynx or lion

And therefore where there are supposed two different ideas, marked by two different names, which are not as distinguishable as the sounds that stand for them, there never fails to be confusion; and where any ideas are distinct as the ideas of those two sounds they are marked by, there can be between them no confusion. The way to prevent confusion is to collect and unite into one complex idea, as precisely as is possible, all those ingredients whereby it is differenced from others; and to these ingredients, so united in a determinate number and order, apply steadily the same name.

And therefore where there are supposed two different ideas, marked by two different names, which are not as distinguishable as the sounds that stand for them, there never fails to be confusion; and where any ideas are distinct as the ideas of those two sounds they are marked by, there can be between them no confusion. The way to prevent confusion is to collect and unite into one complex idea, as precisely as is possible, all those ingredients whereby it is differenced from others; and to these ingredients, so united in a determinate number and order, apply steadily the same name.

But this neither accommodating men’s ease or vanity—nor serving any design but that of naked truth, which is not always the thing aimed at—such exactness is rather to be wished than hoped for.

And since the loose application of names, to undetermined, variable, and almost no ideas, serves both to cover our own ignorance, as well as to perplex and confound others, (which goes for learning and superiority in knowledge,) it is no wonder that most men should use it themselves, whilst they complain of it in others.

Though I think no small part of the confusion to be found in the notions of men might, by care and ingenuity, be avoided, yet I am far from concluding it everywhere willful. Some ideas are so complex, and made up of so many parts, that the memory does not easily retain the very same precise combination of simple ideas under one name: much less are we able constantly to divine for what precise complex idea such a name stands in another man’s use of it. From the first of these, follows confusion in a man’s own reasonings and opinions within himself; from the latter, frequent confusion in discoursing and arguing with others.

—John Locke; An Essay on Human Understanding

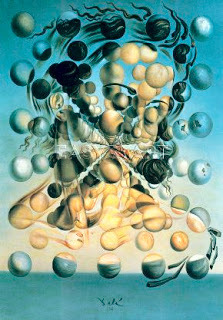

Painting: Salvador Dali, Galatea of the Spheres

And therefore where there are supposed two different ideas, marked by two different names, which are not as distinguishable as the sounds that stand for them, there never fails to be confusion; and where any ideas are distinct as the ideas of those two sounds they are marked by, there can be between them no confusion. The way to prevent confusion is to collect and unite into one complex idea, as precisely as is possible, all those ingredients whereby it is differenced from others; and to these ingredients, so united in a determinate number and order, apply steadily the same name.

And therefore where there are supposed two different ideas, marked by two different names, which are not as distinguishable as the sounds that stand for them, there never fails to be confusion; and where any ideas are distinct as the ideas of those two sounds they are marked by, there can be between them no confusion. The way to prevent confusion is to collect and unite into one complex idea, as precisely as is possible, all those ingredients whereby it is differenced from others; and to these ingredients, so united in a determinate number and order, apply steadily the same name. But this neither accommodating men’s ease or vanity—nor serving any design but that of naked truth, which is not always the thing aimed at—such exactness is rather to be wished than hoped for.

And since the loose application of names, to undetermined, variable, and almost no ideas, serves both to cover our own ignorance, as well as to perplex and confound others, (which goes for learning and superiority in knowledge,) it is no wonder that most men should use it themselves, whilst they complain of it in others.

Though I think no small part of the confusion to be found in the notions of men might, by care and ingenuity, be avoided, yet I am far from concluding it everywhere willful. Some ideas are so complex, and made up of so many parts, that the memory does not easily retain the very same precise combination of simple ideas under one name: much less are we able constantly to divine for what precise complex idea such a name stands in another man’s use of it. From the first of these, follows confusion in a man’s own reasonings and opinions within himself; from the latter, frequent confusion in discoursing and arguing with others.

—John Locke; An Essay on Human Understanding

Painting: Salvador Dali, Galatea of the Spheres

Published on April 06, 2013 07:12

March 29, 2013

A Limited and Unprofitable Craft

Modern scribblers have superseded all the good old authors. The writers whom you suppose in vogue, because they happened to be so when [an old edition was] last in circulation, have long since had their day. [One author’s work,] the immortality of which was so fondly predicted by his admirers, and which, in truth, is full of noble thoughts, delicate images, and graceful turns of language, is now scarcely ever mentioned. [Another] has strutted into obscurity; and even [one of significant renown,] though his writings were once the delight of a court, and apparently perpetuated by a proverb, is now scarcely known even by name.

Modern scribblers have superseded all the good old authors. The writers whom you suppose in vogue, because they happened to be so when [an old edition was] last in circulation, have long since had their day. [One author’s work,] the immortality of which was so fondly predicted by his admirers, and which, in truth, is full of noble thoughts, delicate images, and graceful turns of language, is now scarcely ever mentioned. [Another] has strutted into obscurity; and even [one of significant renown,] though his writings were once the delight of a court, and apparently perpetuated by a proverb, is now scarcely known even by name.A whole crowd of authors who wrote and wrangled at the time, have likewise gone down, with all their writings and their controversies. Wave after wave of succeeding literature has rolled over them, until they are buried so deep, that it is only now and then that some industrious diver after fragments of antiquity brings up a specimen for the gratification of the curious.

For my part, . . . I consider this mutability of language a wise precaution of Providence for the benefit of the world at large, and of authors in particular. To reason from analogy, we daily behold the varied and beautiful tribes of vegetables springing up, flourishing, adorning the fields for a short time, and then fading into dust, to make way for their successors. Were not this the case, the fecundity of nature would be a grievance instead of a blessing. The earth would groan with rank and excessive vegetation, and its surface become a tangled wilderness. In like manner the works of genius and learning decline, and make way for subsequent productions.

Language gradually varies, and with it fade away the writings of authors who have flourished their allotted time; otherwise, the creative powers of genius would overstock the world, and the mind would be completely bewildered in the endless mazes of literature.

Formerly there were some restraints on this excessive multiplication. Works had to be transcribed by hand, which was a slow and laborious operation; they were written either on parchment, which was expensive, so that one work was often erased to make way for another; or on papyrus, which was fragile and extremely perishable. Authorship was a limited and unprofitable craft, pursued chiefly by monks in the leisure and solitude of their cloisters. The accumulation of manuscripts was slow and costly, and confined almost entirely to monasteries. To these circumstances it may, in some measure, be owing that we have not been inundated by the intellect of antiquity; that the fountains of thought have not been broken up, and modern genius drowned in the deluge.

But the inventions of paper and the press have put an end to all these restraints. They have made everyone a writer, and enabled every mind to pour itself into print, and diffuse itself over the whole intellectual world. The consequences are alarming. The stream of literature has swollen into a torrent—augmented into a river—expanded into a sea.

—Washington Irving; Essay; The Mutability of Literature; The Oxford Book of American Essays

Painting: Gabriel Metsu, Dutch Master (1629–1667)

Published on March 29, 2013 17:58

March 10, 2013

The Sunless Earth

Thus, when the night comes down in this calm, changeless realm, nothing indicates its approach; the sun pursuing his path of fire, appears suddenly to hear some mysterious mandate summoning him to abandon his dominion, and, drunk with his own glory, he seems impelled to perish as he lived, in radiance unendurable, for, rushing headlong down the steep blue vault, he plunges suddenly below the dark horizon and is seen no more!

Thus, when the night comes down in this calm, changeless realm, nothing indicates its approach; the sun pursuing his path of fire, appears suddenly to hear some mysterious mandate summoning him to abandon his dominion, and, drunk with his own glory, he seems impelled to perish as he lived, in radiance unendurable, for, rushing headlong down the steep blue vault, he plunges suddenly below the dark horizon and is seen no more!One moment his beams stretch across the heaven, like the great bars of the golden gate of paradise, then he draws them after him and leaves the empire to his rival night.

She meanwhile rises in her gloomy garments, as though to be his great chief mourner, and ascends with swiftest tread the ethereal vault, devouring as she moves along the ruins of the sunshine, whilst from her deepening shadows, brightest stars are born—in token that the Eternal can cause the darkness to bring forth light. Then when like a queen she has taken her throne in heaven, she stretches out her heavy mourning veil and lets it fall upon the sunless earth, over whose shrouded beauty she sits brooding till the dawn.

Felicia Skene (1821–1899)

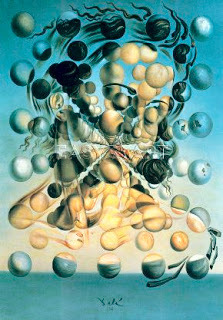

Painting: Claude Monet, Cathedral at Rouen

Published on March 10, 2013 09:44

February 27, 2013

A Mere Glance

A Gentle Hand Invokes the Music of the OrchestraHis glance was as effective as the spoken words of a lover, and more. They called for no immediate decision, and could not be answered.

A Gentle Hand Invokes the Music of the OrchestraHis glance was as effective as the spoken words of a lover, and more. They called for no immediate decision, and could not be answered.People in general attach too much importance to words. They are under the illusion that talking effects great results. As a matter of fact, words are, as a rule, the shallowest portion of all the argument. They but dimly represent the great surging feelings and desires which lie behind. When the distraction of the tongue is removed, the heart listens.

In this conversation she heard, instead of his words, the voices of the things which he represented. How suave was the counsel of his appearance! How feelingly did his superior state speak for itself!

The growing desire he felt for her lay upon her spirit as a gentle hand. She did not need to tremble at all, because it was invisible; she did not need to worry over what other people would say—what she herself would say—because it had no tangibility. She was being pleaded with, persuaded, led into denying old rights and assuming new ones, and yet there were no words to prove it. Such conversation as was indulged in held the same relationship to the actual mental enactments of the twain that the low music of the orchestra does to the dramatic incident which it is used to cover.

Theodore Dreiser, Sister Carrie

Painting: Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry (1728-1796)

Published on February 27, 2013 17:45

February 18, 2013

By Diligent Study of Shades and Shadows

Entering that gable-ended Spouter-Inn, you found yourself in a wide, low, straggling entry with old-fashioned wainscots, reminding one of the bulwarks of some condemned old craft.

Entering that gable-ended Spouter-Inn, you found yourself in a wide, low, straggling entry with old-fashioned wainscots, reminding one of the bulwarks of some condemned old craft.On one side hung a very large oil painting so thoroughly besmoked, and every way defaced, that in the unequal crosslights by which you viewed it, it was only by diligent study and a series of systematic visits to it, and careful inquiry of the neighbors, that you could any way arrive at an understanding of its purpose. Such unaccountable masses of shades and shadows, that at first you almost thought some ambitious young artist, in the time of the New England hags, had endeavored to delineate chaos bewitched. But by dint of much and earnest contemplation, and oft repeated ponderings, and especially by throwing open the little window towards the back of the entry, you at last come to the conclusion that such an idea, however wild, might not be altogether unwarranted.

But what most puzzled and confounded you was a long, limber, portentous, black mass of something hovering in the centre of the picture over three blue, dim, perpendicular lines floating in a nameless yeast. A boggy, soggy, squitchy picture truly, enough to drive a nervous man distracted. Yet was there a sort of indefinite, half-attained, unimaginable sublimity about it that fairly froze you to it, till you involuntarily took an oath with yourself to find out what that marvellous painting meant. Ever and anon a bright, but, alas, deceptive idea would dart you through.—It's the Black Sea in a midnight gale.

— Herman Melville, Moby Dick

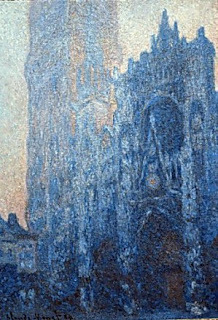

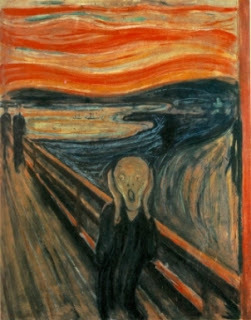

Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893)

Published on February 18, 2013 16:30

February 6, 2013

Our Own Natural Gifts

There is no quality of style that can be gained by reading writers who possess it; whether it be persuasiveness, imagination, the gift of drawing comparisons, boldness, bitterness, brevity, grace, ease of expression or wit, unexpected contrasts, a laconic or naive manner, and the like.

There is no quality of style that can be gained by reading writers who possess it; whether it be persuasiveness, imagination, the gift of drawing comparisons, boldness, bitterness, brevity, grace, ease of expression or wit, unexpected contrasts, a laconic or naive manner, and the like. But if these qualities are already in us, exist, that is to say, potentially, we can call them forth and bring them to consciousness; we can learn the purposes to which they can be put; we can be strengthened in our inclination to use them, or get courage to do so; we can judge by examples the effect of applying them, and so acquire the correct use of them; and of course it is only when we have arrived at that point that we actually possess these qualities.

The only way in which reading can form style is by teaching us the use to which we can put our own natural gifts.

— Arthur Schopenhauer, "Reading and Books," Essays of Schopenhauer

Painting: Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, (1796 - 1875) Interrupted Reading

See also: Your Natural Voice as a Writer

Published on February 06, 2013 08:59

January 3, 2013

History of a Knight-Errant

Suddenly there is presented to his sight a strong castle (or gorgeous palace) with walls of massy gold, turrets of diamond and gates of jacinth; in short, so marvelous is its structure that though the materials of which it is built are nothing less than diamonds, carbuncles, rubies, pearls, gold, and emeralds, the workmanship is still more rare.

Suddenly there is presented to his sight a strong castle (or gorgeous palace) with walls of massy gold, turrets of diamond and gates of jacinth; in short, so marvelous is its structure that though the materials of which it is built are nothing less than diamonds, carbuncles, rubies, pearls, gold, and emeralds, the workmanship is still more rare.And after having seen all this, what can be more charming than to see how a bevy of damsels comes forth from the gate of the castle in gay and gorgeous attire, such that, were I to set myself now to depict it as the histories describe it to us, I should never have done; and then how she who seems to be the first among them all takes the bold knight (who plunged into the boiling lake) by the hand, and without addressing a word to him leads him into the rich palace (or castle,) and strips him as naked as when his mother bore him, and bathes him in lukewarm water, and anoints him all over with sweet-smelling unguents, and clothes him in a shirt of the softest sendal, all scented and perfumed, while another damsel comes and throws over his shoulders a mantle which is said to be worth at the very least a city, (and even more?).

How charming it is, then, when they tell us how, after all this, they lead him to another chamber where he finds the tables set out in such style that he is filled with amazement and wonder; to see how they pour out water for his hands distilled from amber and sweet-scented flowers; how they seat him on an ivory chair; to see how the damsels wait on him all in profound silence; how they bring him such a variety of dainties so temptingly prepared that the appetite is at a loss which to select; to hear the music that resounds while he is at table, by whom or whence produced he knows not.

And then when the repast is over and the tables removed, for the knight to recline in the chair, (picking his teeth perhaps as usual,) and a damsel, much lovelier than any of the others, to enter unexpectedly by the chamber door, (and herself by his side,) and begin to tell him what the castle is, and how she is held enchanted there, and other things that amaze the knight and astonish . . .

* * *

But I will not expatiate any further upon this, as it may be gathered from it that whatever part of whatever history of a knight-errant one reads, it will fill the reader, whoever he be, with delight and wonder; and take my advice, sir, and, as I said before, read these books and you will see how they will banish any melancholy you may feel and raise your spirits should they be depressed.

Miguel de Cervantes; Don Quixote ; translated by John Ormsby

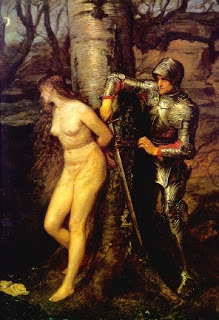

Painting: John Everett Millais (1829 - 1896), The Knight Errant

Published on January 03, 2013 08:39

December 30, 2012

The Admission and Omission of Details

Foolish critics often betray their ignorance by saying that a painter or a writer "only copies what he has seen, or puts down what he has known."

Foolish critics often betray their ignorance by saying that a painter or a writer "only copies what he has seen, or puts down what he has known." They forget that no man imagines what he has not seen or known, and that it is in the selection of characteristic details that the artistic power is manifested.

Those who suppose that familiarity with scenes or characters enables a painter or a novelist to "copy" them with artistic effect, forget the well-known fact that the vast majority of men are painfully incompetent to avail themselves of this familiarity, and cannot form vivid pictures even to themselves of scenes in which they pass their daily lives; and if they could imagine these, they would need the delicate selective instinct to guide them in the admission and omission of details, as well as in the grouping of the images.

Let any one try to "copy" the wife or brother he knows so well,—to make a human image which shall speak and act so as to impress strangers with a belief in its truth,—and he will then see that the much-despised reliance on actual experience is not the mechanical procedure it is believed to be.

George Henry Lewes, The Principles of Success in Literature

Paiting: Claude Monet, Pathway in Monet's Garden at Giverny

Published on December 30, 2012 12:20

December 28, 2012

The Subject of Ridicule

Not only did the district court here fail to identify any of the [appropriate] factors that would have supported a dismissal with prejudice, but it also in effect adopted a "three strikes" rule for securities fraud pleading that has no support in precedent. In the district court's view, appellant had had "three bites" and deserved no more opportunities to comply with the stringent requirements of the [Statute]. Simply counting the number of times a plaintiff has filed a complaint cannot, however, substitute for an analysis of whether the rigorous standards of the [Statute] have been met.

Not only did the district court here fail to identify any of the [appropriate] factors that would have supported a dismissal with prejudice, but it also in effect adopted a "three strikes" rule for securities fraud pleading that has no support in precedent. In the district court's view, appellant had had "three bites" and deserved no more opportunities to comply with the stringent requirements of the [Statute]. Simply counting the number of times a plaintiff has filed a complaint cannot, however, substitute for an analysis of whether the rigorous standards of the [Statute] have been met.The [Court's] opinion regrettably (but deliberately) reiterates the same cliche used by the district court. Metaphors enrich writing only to the extent that they add something to more pedestrian descriptions. Cliches do the opposite; they deaden our senses to the nuances of language so often critical to our common law tradition. The interpretation and application of statutes, rules, and case law frequently depends on whether we can discriminate among subtle differences of meaning. The biting of apples does not help us. [Emphasis added.]

* * *[The] process of adaptation and progress, embedded in our legal tradition, necessitates the careful exposition of prose in our opinion writing. A cliche like "three bites at the apple" provides a formalistic rule that does not account for the particularities of an individual case.

The problem of cliches as a substitute for rational analysis is particularly acute in the legal profession, where our style of writing is often deservedly the subject of ridicule.

Reinhardt, Circuit Judge, concurring Opinion. Eminence Capital, LLC v. Aspeon, Inc., 316 F. 3d 1048 (9th Cir. 2003)

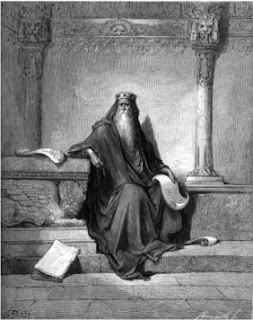

Illustration: Gustave Doré (1832 -1883), King Solomon Writing Proverbs

Published on December 28, 2012 04:51

December 8, 2012

Composition 101

Random Thoughts, Great Ideas and the Elements of StyleThe writing process, by any other name, is the series of steps that takes the writer from a goal to a collection of related ideas, to organized drafts and to a finished piece. If a term paper, an office memo or a blog post is your goal, the process is the same. The exercise is called “composition.”

Good writing has an aim, is structured and must be composed. The purpose, or aim, of a written piece can be any number of things. Some examples are: to instruct, to lay out an argument that persuades, to describe an experience, to flesh out a point of view or to tell a story. To begin writing, you need ideas.

Good writing has an aim, is structured and must be composed. The purpose, or aim, of a written piece can be any number of things. Some examples are: to instruct, to lay out an argument that persuades, to describe an experience, to flesh out a point of view or to tell a story. To begin writing, you need ideas.

Let’s Collect Our Thoughts. If we were paid for our thoughts, we’d all be millionaires. Our minds are either at work or wandering in aimless thought. It can take great effort to quiet the mind. Yogis spend years practicing meditation so they can still the mind and achieve a state of restful alertness.

It’s easy for us to imagine likely events in the life of the quarrelsome couple who was with us in line at the supermarket. We may have a vivid idea what our boss or spouse will say and do if we can’t keep the big appointment. We know firsthand the unbridled joy of a child’s laughter.

Maybe in some future time, a computer will be able to capture our thoughts, reduce them to writing and save them to a searchable database. This would be an invaluable service for writers. Unfortunately, we’re not there yet.

Let’s Distill Our Best Ideas. It’s a pity how often we dismiss a thought as trivial and unworthy of daylight only to admire the same thought when it falls from the lips of someone we respect. How often do we wonder in amazement to see a sliver of our own notion, or of our own experience, recounted in the writings of another?

Artists Compose. The task of a composer is to organize his ideas into a pleasing and self-sustaining whole, using the elements of his art. The painter is concerned with lines, shapes, figures, contrast and color. The composer of music is concerned with notes, chords, tempo, harmonies and melodies.

Writers also Compose. Most of us can recall a class or an assignment of English Composition. I don’t remember it being explained to me this way, but the goal of composition is to create a piece by organizing related parts.

The most basic unit in writing is an idea in the form of a sentence. A writer's ideas can take the form of facts, impressions, anecdotes and arguments. The writer begins with a list of related ideas, builds on a theme and sub-themes and organizes it into a framework.

Like the composer of music, the goal of the writer is to create a final piece that is a pleasing and self-sustaining whole.

I always had trouble with the self-sustaining part in elementary school. When asked why I didn’t mention a crucial point in an essay, my very serious reply was, “I thought the teacher knew that.”

The First Draft is Never a Masterpiece. Arriving at the final piece involves time and effort invested in rewriting. The first few drafts can always be improved. Grammar and usage may have to be corrected. Your story may need tweaking to evoke the right mood and to strike the proper emphasis. The argument may need to be restated and made to sound more convincing. You may need to clarify an important point that is glossed over. You may have to reorganize your thoughts so that a unifying theme shines through more clearly for the reader.

Follow Rules and Conventions. It is no coincidence that the most graceful ballerina will be found among those who have mastered the basics of their art. Don’t look at rules and conventions as stifling constraints; rather, use them to elevate your art form. Your talent will shine if you master the basics.

William Shakespeare used iambic pentameter to structure verses in his plays and sonnets. It elevated his art. No one suggests that his adherence to convention limited his art. And no one suggests that he used this meter as a crutch because he didn’t have enough talent.

Painting: Jean-Marc Nattier, Terpsichore, Muse of Music and Dance, Circa 1789

What has your experience with English Composition been like?

Good writing has an aim, is structured and must be composed. The purpose, or aim, of a written piece can be any number of things. Some examples are: to instruct, to lay out an argument that persuades, to describe an experience, to flesh out a point of view or to tell a story. To begin writing, you need ideas.

Good writing has an aim, is structured and must be composed. The purpose, or aim, of a written piece can be any number of things. Some examples are: to instruct, to lay out an argument that persuades, to describe an experience, to flesh out a point of view or to tell a story. To begin writing, you need ideas.Let’s Collect Our Thoughts. If we were paid for our thoughts, we’d all be millionaires. Our minds are either at work or wandering in aimless thought. It can take great effort to quiet the mind. Yogis spend years practicing meditation so they can still the mind and achieve a state of restful alertness.

It’s easy for us to imagine likely events in the life of the quarrelsome couple who was with us in line at the supermarket. We may have a vivid idea what our boss or spouse will say and do if we can’t keep the big appointment. We know firsthand the unbridled joy of a child’s laughter.

Maybe in some future time, a computer will be able to capture our thoughts, reduce them to writing and save them to a searchable database. This would be an invaluable service for writers. Unfortunately, we’re not there yet.

Let’s Distill Our Best Ideas. It’s a pity how often we dismiss a thought as trivial and unworthy of daylight only to admire the same thought when it falls from the lips of someone we respect. How often do we wonder in amazement to see a sliver of our own notion, or of our own experience, recounted in the writings of another?

Artists Compose. The task of a composer is to organize his ideas into a pleasing and self-sustaining whole, using the elements of his art. The painter is concerned with lines, shapes, figures, contrast and color. The composer of music is concerned with notes, chords, tempo, harmonies and melodies.

Writers also Compose. Most of us can recall a class or an assignment of English Composition. I don’t remember it being explained to me this way, but the goal of composition is to create a piece by organizing related parts.

The most basic unit in writing is an idea in the form of a sentence. A writer's ideas can take the form of facts, impressions, anecdotes and arguments. The writer begins with a list of related ideas, builds on a theme and sub-themes and organizes it into a framework.

Like the composer of music, the goal of the writer is to create a final piece that is a pleasing and self-sustaining whole.

I always had trouble with the self-sustaining part in elementary school. When asked why I didn’t mention a crucial point in an essay, my very serious reply was, “I thought the teacher knew that.”

The First Draft is Never a Masterpiece. Arriving at the final piece involves time and effort invested in rewriting. The first few drafts can always be improved. Grammar and usage may have to be corrected. Your story may need tweaking to evoke the right mood and to strike the proper emphasis. The argument may need to be restated and made to sound more convincing. You may need to clarify an important point that is glossed over. You may have to reorganize your thoughts so that a unifying theme shines through more clearly for the reader.

Follow Rules and Conventions. It is no coincidence that the most graceful ballerina will be found among those who have mastered the basics of their art. Don’t look at rules and conventions as stifling constraints; rather, use them to elevate your art form. Your talent will shine if you master the basics.

William Shakespeare used iambic pentameter to structure verses in his plays and sonnets. It elevated his art. No one suggests that his adherence to convention limited his art. And no one suggests that he used this meter as a crutch because he didn’t have enough talent.

Painting: Jean-Marc Nattier, Terpsichore, Muse of Music and Dance, Circa 1789

What has your experience with English Composition been like?

Published on December 08, 2012 23:38