Gary Gauthier's Blog, page 2

January 9, 2015

The Symbol of Our Labor

Hidden wisdom and mysterious revelations.

The peril of our new way of life was not lest we should fail in becoming real-life farmers, but that we should probably cease to be anything else. While our enterprise lay all in theory, we had pleased ourselves with delectable visions of the spiritualization of labor. It was to be our form of prayer and ceremonial of worship.

Each stroke of the hoe was to uncover some aromatic root of wisdom, heretofore hidden from the sun. Pausing in the field, to let the wind exhale the moisture from our foreheads, we were to look upward, and catch glimpses into the far-off soul of truth. In this point of view, matters did not turn out quite so well as we anticipated.

It is very true that, sometimes, gazing casually around me, out of the midst of my toil, I used to discern a richer picturesqueness in the visible scene of earth and sky. There was, at such moments, a novelty, an unwonted aspect, on the face of Nature, as if she had been taken by surprise and seen at unawares, with no opportunity to put off her real look, and assume the mask with which she mysteriously hides herself from mortals. But this was all.

The clods of earth, which we so constantly belabored and turned over and over, were never etherealized into thought. Our thoughts, on the contrary, were fast becoming cloddish. Our labor symbolized nothing, and left us mentally sluggish in the dusk of the evening.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Blithedale Romance

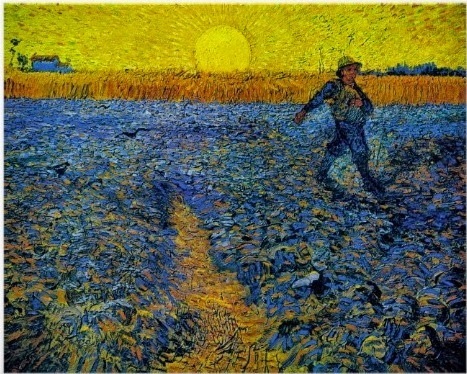

Painting; Van Gogh, The Sower

The peril of our new way of life was not lest we should fail in becoming real-life farmers, but that we should probably cease to be anything else. While our enterprise lay all in theory, we had pleased ourselves with delectable visions of the spiritualization of labor. It was to be our form of prayer and ceremonial of worship.

Each stroke of the hoe was to uncover some aromatic root of wisdom, heretofore hidden from the sun. Pausing in the field, to let the wind exhale the moisture from our foreheads, we were to look upward, and catch glimpses into the far-off soul of truth. In this point of view, matters did not turn out quite so well as we anticipated.

It is very true that, sometimes, gazing casually around me, out of the midst of my toil, I used to discern a richer picturesqueness in the visible scene of earth and sky. There was, at such moments, a novelty, an unwonted aspect, on the face of Nature, as if she had been taken by surprise and seen at unawares, with no opportunity to put off her real look, and assume the mask with which she mysteriously hides herself from mortals. But this was all.

The clods of earth, which we so constantly belabored and turned over and over, were never etherealized into thought. Our thoughts, on the contrary, were fast becoming cloddish. Our labor symbolized nothing, and left us mentally sluggish in the dusk of the evening.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Blithedale Romance

Painting; Van Gogh, The Sower

Published on January 09, 2015 08:02

January 2, 2015

Pascal's Wager

When is a game worth the candle?Fermat and Pascal founded the essential rules that govern all games of chance. T[he rules] can be used by gamblers to define perfect playing and betting strategies. Furthermore, these laws of probability have found applications in a whole series of situations, ranging from speculating in the stock market to estimating the probability of a nuclear accident.

A mathematical formula leads to infinity.Pascal was even convinced that that he could use his theories to justify a belief in God. He stated that "the excitement that a gambler feels when making a bet is equal to the amount he might win times the probability of winning it." He then argued that the possible prize of eternal happiness has an infinite value and that the probability of entering heaven by leading a virtuous life, no matter how small is certainly finite. Therefore, according to Pascal's definition, religion was a game of infinite excitement and one worth playing, because multiplying and infinite prize by a finite probability results in infinity.

— Simon Singh, Fermat's Enigma

Painting: Caravaggio: The Cardsharps

A mathematical formula leads to infinity.Pascal was even convinced that that he could use his theories to justify a belief in God. He stated that "the excitement that a gambler feels when making a bet is equal to the amount he might win times the probability of winning it." He then argued that the possible prize of eternal happiness has an infinite value and that the probability of entering heaven by leading a virtuous life, no matter how small is certainly finite. Therefore, according to Pascal's definition, religion was a game of infinite excitement and one worth playing, because multiplying and infinite prize by a finite probability results in infinity.

— Simon Singh, Fermat's Enigma

Painting: Caravaggio: The Cardsharps

Published on January 02, 2015 10:15

August 26, 2014

Literary License

For centuries a small number of writers were confronted by many thousands of readers. This changed toward the end of the last century. With the increasing extension of the press, which kept placing new political, religious, scientific, professional, and local organs before the readers, an increasing number of readers became writers—at first, occasional ones.

For centuries a small number of writers were confronted by many thousands of readers. This changed toward the end of the last century. With the increasing extension of the press, which kept placing new political, religious, scientific, professional, and local organs before the readers, an increasing number of readers became writers—at first, occasional ones.It began with the daily press opening to its readers space for “letters to the editor.” And today there is hardly a gainfully employed [individual] who could not, in principle, find an opportunity to publish somewhere or other comments on his work, grievances, documentary reports, or that sort of thing. Thus, the distinction between author and public is about to lose its basic character. The difference becomes merely functional; it may vary from case to case.

At any moment the reader is ready to turn into a writer. As expert, which he had to become willy-nilly in an extremely specialized work process, even if only in some minor respect, the reader gains access to authorship. In [many instances] work itself is given a voice. To present it verbally is part of a man’s ability to perform the work. Literary license is now founded on polytechnic rather than specialized training and thus becomes common property.

All this can easily be applied to the film, where transitions that in literature took centuries have come about in a decade. . . .

— Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936)

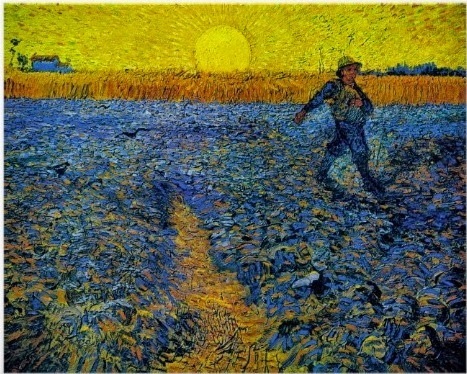

Painting: Mir Sayyid Ali, Mughal, A Young Scribe, c. 1550, watercolor and gold on paper

Published on August 26, 2014 12:30

April 30, 2014

The Spell of the Spoken Word

Nothing is more unaccountable than the spell that often lurks in a spoken word. A thought may be present to the mind so distinctly that no utterance could make it more so; and two minds may be conscious of the same thought, in which one or both take the most profound interest; but as long as it remains unspoken, their familiar talk flows quietly over the hidden idea, as a rivulet may sparkle and dimple over something sunken in its bed.

Nothing is more unaccountable than the spell that often lurks in a spoken word. A thought may be present to the mind so distinctly that no utterance could make it more so; and two minds may be conscious of the same thought, in which one or both take the most profound interest; but as long as it remains unspoken, their familiar talk flows quietly over the hidden idea, as a rivulet may sparkle and dimple over something sunken in its bed.But speak the word, and it is like bringing up a drowned body out of the deepest pool of the rivulet, which has been aware of the horrible secret all along, in spite of its smiling surface.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun

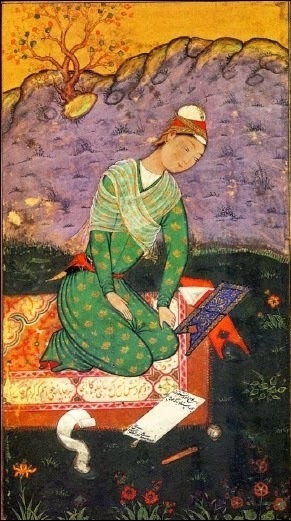

Painting: Caspar David Friedrich, ca. 1832

Published on April 30, 2014 05:43

March 19, 2014

I knew I had a fever

Phases of the Disease: a brick in a giddy place; a steal beam in a whirling engine; my own person

That I had a fever and was avoided, that I suffered greatly, that I often lost my reason, that the time seemed interminable, that I confounded impossible existences with my own identity; that I was a brick in the house-wall, and yet entreating to be released from the giddy place where the builders had set me; that I was a steel beam of a vast engine, clashing and whirling over a gulf, and yet that I implored in my own person to have the engine stopped, and my part in it hammered off; that I passed through these phases of disease, I know of my own remembrance, and did in some sort know at the time.

That I had a fever and was avoided, that I suffered greatly, that I often lost my reason, that the time seemed interminable, that I confounded impossible existences with my own identity; that I was a brick in the house-wall, and yet entreating to be released from the giddy place where the builders had set me; that I was a steel beam of a vast engine, clashing and whirling over a gulf, and yet that I implored in my own person to have the engine stopped, and my part in it hammered off; that I passed through these phases of disease, I know of my own remembrance, and did in some sort know at the time.

—Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

Painting: Amedeo Modigliani, Little Girl in Blue (1918)

That I had a fever and was avoided, that I suffered greatly, that I often lost my reason, that the time seemed interminable, that I confounded impossible existences with my own identity; that I was a brick in the house-wall, and yet entreating to be released from the giddy place where the builders had set me; that I was a steel beam of a vast engine, clashing and whirling over a gulf, and yet that I implored in my own person to have the engine stopped, and my part in it hammered off; that I passed through these phases of disease, I know of my own remembrance, and did in some sort know at the time.

That I had a fever and was avoided, that I suffered greatly, that I often lost my reason, that the time seemed interminable, that I confounded impossible existences with my own identity; that I was a brick in the house-wall, and yet entreating to be released from the giddy place where the builders had set me; that I was a steel beam of a vast engine, clashing and whirling over a gulf, and yet that I implored in my own person to have the engine stopped, and my part in it hammered off; that I passed through these phases of disease, I know of my own remembrance, and did in some sort know at the time.—Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

Painting: Amedeo Modigliani, Little Girl in Blue (1918)

Published on March 19, 2014 11:03

February 10, 2014

A Glimpse of the Master's Genius

An idea that might vanish in the twinkling of an eye is captured on an old scrap of paper

There were curious little treasures of art and bits of antiquity strewn about.

There were curious little treasures of art and bits of antiquity strewn about.

As interesting as any of these relics was a large portfolio of old drawings, some of which, in the opinion of their possessor, bore evidence on their faces of the touch of master-hands. Very ragged and ill conditioned they mostly were, yellow with time, and tattered with rough usage; and, in their best estate, the designs had been scratched rudely with pen and ink, on coarse paper, or, if drawn with charcoal or a pencil, were now half rubbed out.

You would not anywhere see rougher and homelier things than these. But this hasty rudeness made the sketches only the more valuable; because the artist seemed to have bestirred himself at the pinch of the moment, snatching up whatever material was nearest, so as to seize the first glimpse of an idea that might vanish in the twinkling of an eye. Thus, by the spell of a creased, soiled, and discolored scrap of paper, you were enabled to steal close to an old master, and watch him in the very effervescence of his genius.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun

Drawing: Rembrandt, Self-portrait, pen, brush and ink on paper, c. 1628

There were curious little treasures of art and bits of antiquity strewn about.

There were curious little treasures of art and bits of antiquity strewn about. As interesting as any of these relics was a large portfolio of old drawings, some of which, in the opinion of their possessor, bore evidence on their faces of the touch of master-hands. Very ragged and ill conditioned they mostly were, yellow with time, and tattered with rough usage; and, in their best estate, the designs had been scratched rudely with pen and ink, on coarse paper, or, if drawn with charcoal or a pencil, were now half rubbed out.

You would not anywhere see rougher and homelier things than these. But this hasty rudeness made the sketches only the more valuable; because the artist seemed to have bestirred himself at the pinch of the moment, snatching up whatever material was nearest, so as to seize the first glimpse of an idea that might vanish in the twinkling of an eye. Thus, by the spell of a creased, soiled, and discolored scrap of paper, you were enabled to steal close to an old master, and watch him in the very effervescence of his genius.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Marble Faun

Drawing: Rembrandt, Self-portrait, pen, brush and ink on paper, c. 1628

Published on February 10, 2014 18:08

February 3, 2014

A Novel Idea

How the diverse, contemporary and vulgar ended up becoming useful

In the thirteenth century Saint Bonaventure, a Franciscan monk, described four ways a person could make books: copy a work whole, copy from several works at once, copy an existing work with his own additions, or write out some of his own work with additions from elsewhere. Each of these categories had its own name, like scribe or author, but Bonaventure does not seem to have considered—and certainly didn’t describe—the possibility of anyone creating a wholly original work. In this period, very few books were in existence and a good number of them were copies of the Bible, so the idea of bookmaking was centered on re-creating and recombining existing works far more than on producing novel ones.

In the thirteenth century Saint Bonaventure, a Franciscan monk, described four ways a person could make books: copy a work whole, copy from several works at once, copy an existing work with his own additions, or write out some of his own work with additions from elsewhere. Each of these categories had its own name, like scribe or author, but Bonaventure does not seem to have considered—and certainly didn’t describe—the possibility of anyone creating a wholly original work. In this period, very few books were in existence and a good number of them were copies of the Bible, so the idea of bookmaking was centered on re-creating and recombining existing works far more than on producing novel ones.

Movable type removed that bottleneck, and the first thing the growing cadre of European printers did was to print more Bibles—lots more Bibles. Printers began publishing Bibles translated into vulgar languages—contemporary languages other than Latin—because priests wanted them, not just as a convenience but as a matter of doctrine.

Then they began putting out new editions of works by Aristotle, Galen, Virgil, and others that had survived from antiquity. And still the presses could produce more.

The next move by the printers was at once simple and astonishing: print lots of new stuff. Prior to movable type, much of the literature available in Europe had been in Latin and was at least a millennium old. And then in a historical eyeblink, books started appearing in local languages, books whose text was months rather than centuries old, books that were, in aggregate, diverse, contemporary, and vulgar. Indeed, the word novel comes from this period, when newness of content was itself new.

—Clay Shirky, Cognitive Surplus

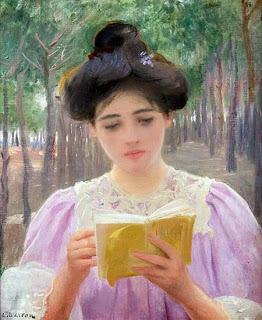

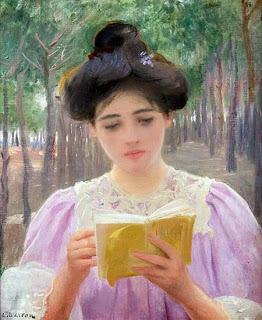

Painting: Laureano Barrau (1863–1957)

In the thirteenth century Saint Bonaventure, a Franciscan monk, described four ways a person could make books: copy a work whole, copy from several works at once, copy an existing work with his own additions, or write out some of his own work with additions from elsewhere. Each of these categories had its own name, like scribe or author, but Bonaventure does not seem to have considered—and certainly didn’t describe—the possibility of anyone creating a wholly original work. In this period, very few books were in existence and a good number of them were copies of the Bible, so the idea of bookmaking was centered on re-creating and recombining existing works far more than on producing novel ones.

In the thirteenth century Saint Bonaventure, a Franciscan monk, described four ways a person could make books: copy a work whole, copy from several works at once, copy an existing work with his own additions, or write out some of his own work with additions from elsewhere. Each of these categories had its own name, like scribe or author, but Bonaventure does not seem to have considered—and certainly didn’t describe—the possibility of anyone creating a wholly original work. In this period, very few books were in existence and a good number of them were copies of the Bible, so the idea of bookmaking was centered on re-creating and recombining existing works far more than on producing novel ones.Movable type removed that bottleneck, and the first thing the growing cadre of European printers did was to print more Bibles—lots more Bibles. Printers began publishing Bibles translated into vulgar languages—contemporary languages other than Latin—because priests wanted them, not just as a convenience but as a matter of doctrine.

Then they began putting out new editions of works by Aristotle, Galen, Virgil, and others that had survived from antiquity. And still the presses could produce more.

The next move by the printers was at once simple and astonishing: print lots of new stuff. Prior to movable type, much of the literature available in Europe had been in Latin and was at least a millennium old. And then in a historical eyeblink, books started appearing in local languages, books whose text was months rather than centuries old, books that were, in aggregate, diverse, contemporary, and vulgar. Indeed, the word novel comes from this period, when newness of content was itself new.

—Clay Shirky, Cognitive Surplus

Painting: Laureano Barrau (1863–1957)

Published on February 03, 2014 18:06

October 21, 2013

A Simple Algorithm

All of them had read science fiction when they were boys or girls.

I was once in New York, and I listened to a talk about the building of private prisons—a huge growth industry in America. The prison industry needs to plan its future growth—how many cells are they going to need? How many prisoners are there going to be, 15 years from now? And they found they could predict it very easily, using a pretty simple algorithm, based on asking what percentage of 10 and 11-year-olds couldn't read. And certainly couldn't read for pleasure.

I was once in New York, and I listened to a talk about the building of private prisons—a huge growth industry in America. The prison industry needs to plan its future growth—how many cells are they going to need? How many prisoners are there going to be, 15 years from now? And they found they could predict it very easily, using a pretty simple algorithm, based on asking what percentage of 10 and 11-year-olds couldn't read. And certainly couldn't read for pleasure.

It's not one to one: you can't say that a literate society has no criminality. But there are very real correlations. And I think some of those correlations, the simplest, come from something very simple. Literate people read fiction.

Fiction has two uses. First, it's a gateway drug to reading. The drive to know what happens next, to want to turn the page, the need to keep going, even if it's hard, because someone's in trouble and you have to know how it's all going to end . . . that's a very real drive.

And it forces you to learn new words, to think new thoughts, to keep going. To discover that reading per se is pleasurable. Once you learn that, you're on the road to reading everything. And reading is key.

* * *

Words are more important than they ever were: we navigate the world with words, and as the world slips onto the web, we need to follow, to communicate and to comprehend what we are reading. . . .

The simplest way to make sure that we raise literate children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity. And that means, at its simplest, finding books that they enjoy, giving them access to those books, and letting them read.

* * *

I was in China in 2007, at the first party-approved science fiction and fantasy convention in Chinese history. And at one point I took a top official aside and asked him Why? Science fiction had been disapproved of for a long time. What had changed?

It's simple, he told me. The Chinese were brilliant at making things if other people brought them the plans. But they did not innovate and they did not invent. They did not imagine. So they sent a delegation to the US, to Apple, to Microsoft, to Google, and they asked the people there who were inventing the future about themselves. And they found that all of them had read science fiction when they were boys or girls.

—Neil Gaiman

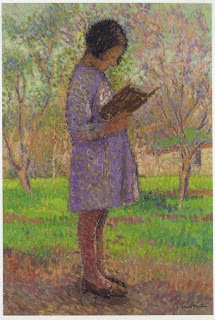

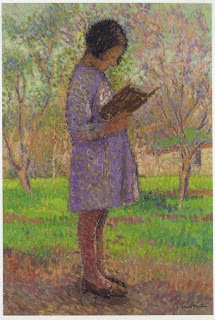

Painting: Henri-Jean Guillaume Martin (1860 - 1943) French impressionist painter

I was once in New York, and I listened to a talk about the building of private prisons—a huge growth industry in America. The prison industry needs to plan its future growth—how many cells are they going to need? How many prisoners are there going to be, 15 years from now? And they found they could predict it very easily, using a pretty simple algorithm, based on asking what percentage of 10 and 11-year-olds couldn't read. And certainly couldn't read for pleasure.

I was once in New York, and I listened to a talk about the building of private prisons—a huge growth industry in America. The prison industry needs to plan its future growth—how many cells are they going to need? How many prisoners are there going to be, 15 years from now? And they found they could predict it very easily, using a pretty simple algorithm, based on asking what percentage of 10 and 11-year-olds couldn't read. And certainly couldn't read for pleasure.It's not one to one: you can't say that a literate society has no criminality. But there are very real correlations. And I think some of those correlations, the simplest, come from something very simple. Literate people read fiction.

Fiction has two uses. First, it's a gateway drug to reading. The drive to know what happens next, to want to turn the page, the need to keep going, even if it's hard, because someone's in trouble and you have to know how it's all going to end . . . that's a very real drive.

And it forces you to learn new words, to think new thoughts, to keep going. To discover that reading per se is pleasurable. Once you learn that, you're on the road to reading everything. And reading is key.

* * *

Words are more important than they ever were: we navigate the world with words, and as the world slips onto the web, we need to follow, to communicate and to comprehend what we are reading. . . .

The simplest way to make sure that we raise literate children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity. And that means, at its simplest, finding books that they enjoy, giving them access to those books, and letting them read.

* * *

I was in China in 2007, at the first party-approved science fiction and fantasy convention in Chinese history. And at one point I took a top official aside and asked him Why? Science fiction had been disapproved of for a long time. What had changed?

It's simple, he told me. The Chinese were brilliant at making things if other people brought them the plans. But they did not innovate and they did not invent. They did not imagine. So they sent a delegation to the US, to Apple, to Microsoft, to Google, and they asked the people there who were inventing the future about themselves. And they found that all of them had read science fiction when they were boys or girls.

—Neil Gaiman

Painting: Henri-Jean Guillaume Martin (1860 - 1943) French impressionist painter

Published on October 21, 2013 17:40

September 29, 2013

Heavy framework rests on shaky foundation

Musings on the exterior presentment of counterfeit rights

Matthew Maule, the wizard, had been foully wronged out of his homestead, if not out of his life.

Matthew Maule, the wizard, had been foully wronged out of his homestead, if not out of his life.

As for Matthew Maule's posterity, it was supposed now to be extinct. For a very long period after the witchcraft delusion, however, the Maules had continued to inhabit the town where their progenitor had suffered so unjust a death.

To all appearance, they were a quiet, honest, well-meaning race of people, cherishing no malice against individuals or the public for the wrong which had been done them; or if, at their own fireside, they transmitted from father to child any hostile recollection of the wizard's fate and their lost patrimony, it was never acted upon, nor openly expressed. Nor would it have been singular had they ceased to remember that the House of the Seven Gables was resting its heavy framework on a foundation that was rightfully their own.

There is something so massive, stable, and almost irresistibly imposing in the exterior presentment of established rank and great possessions, that their very existence seems to give them a right to exist; at least, so excellent a counterfeit of right, that few poor and humble men have moral force enough to question it, even in their secret minds.

Such is the case now, after so many ancient prejudices have been overthrown; and it was far more so in ante-Revolutionary days, when the aristocracy could venture to be proud, and the low were content to be abased.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The House of the Seven Gables

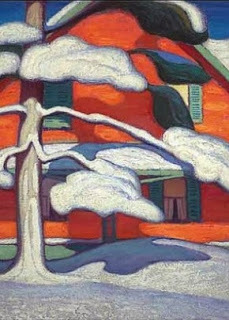

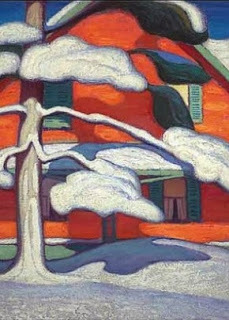

Painting: Lawren Harris (1885 - 1970), Pine Tree and Red House

Matthew Maule, the wizard, had been foully wronged out of his homestead, if not out of his life.

Matthew Maule, the wizard, had been foully wronged out of his homestead, if not out of his life.As for Matthew Maule's posterity, it was supposed now to be extinct. For a very long period after the witchcraft delusion, however, the Maules had continued to inhabit the town where their progenitor had suffered so unjust a death.

To all appearance, they were a quiet, honest, well-meaning race of people, cherishing no malice against individuals or the public for the wrong which had been done them; or if, at their own fireside, they transmitted from father to child any hostile recollection of the wizard's fate and their lost patrimony, it was never acted upon, nor openly expressed. Nor would it have been singular had they ceased to remember that the House of the Seven Gables was resting its heavy framework on a foundation that was rightfully their own.

There is something so massive, stable, and almost irresistibly imposing in the exterior presentment of established rank and great possessions, that their very existence seems to give them a right to exist; at least, so excellent a counterfeit of right, that few poor and humble men have moral force enough to question it, even in their secret minds.

Such is the case now, after so many ancient prejudices have been overthrown; and it was far more so in ante-Revolutionary days, when the aristocracy could venture to be proud, and the low were content to be abased.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The House of the Seven Gables

Painting: Lawren Harris (1885 - 1970), Pine Tree and Red House

Published on September 29, 2013 06:47

September 24, 2013

In the Beginning

THE YEARS OF WHICH I HAVE SPOKEN TO YOU, when I pursued the inner images, were the most important time of my life. Everything else is to be derived from this.

THE YEARS OF WHICH I HAVE SPOKEN TO YOU, when I pursued the inner images, were the most important time of my life. Everything else is to be derived from this. It began at that time, and the later details hardly matter anymore. My entire life consisted in elaborating what had burst forth from the unconscious and flooded me like an enigmatic stream and threatened to break me. That was the stuff and material for more than only one life.

Everything later was merely the outer classification, the scientific elaboration, and the integration into life. But the numinous beginning, which contained everything, was then.

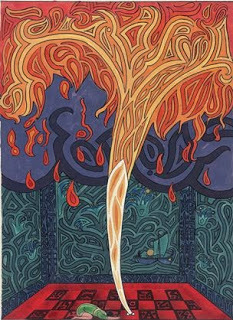

—Carl Jung, 1957

Illustration: Carl Jung, The Red Book

Published on September 24, 2013 11:50