Gawain Barker's Blog

May 30, 2020

Submarine Cook

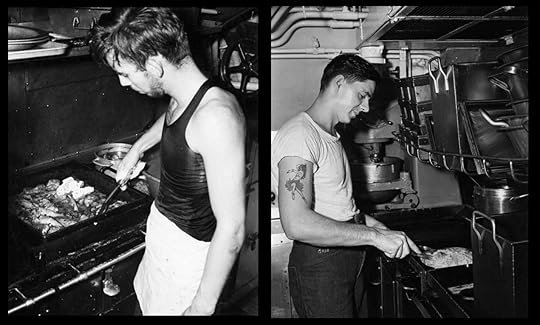

I've worked in some sweat boxes - kitchens as moist and stinky as a wrestler's jock strap, but for true hard-core cooking action there can't have been much tougher than a wartime submarine's galley. From the primitive subs of the Great War, through to the ocean-going fleets of the Second World War, the deep-water cook worked in a world of monstrous adversity. In tiny kitchens like metal cells, these culinary heroes dealt with botheration incomprehensible to us pampered landlubbers today. Just cooking was a challenge. Submarines frequently travelled on the surface and rough seas would turn hot oil and full pots into skin stripping hazards. This bad weather also meant holding on with one hand while trying to prep and cook with the other. The lack of space left little room to move in the kitchen if there was an accident. Sea water and condensation sometimes dripped from overhead and the grinding 40 degree heat produced by a diesel powered steel tube full of sweating men left the bare-chested cooks dizzy on their feet. And of course – there was an ever-present fear of attack. Day after day loomed the very real possibility of the boat's hull being cracked open by enemy bombs or torpedoes, allowing tons of crushing water to pour in and send the screaming crew on a doomed trip to the ocean floor. At over a 100 metres under the sea the most basic conditions for human survival couldn't be taken for granted. On those submarines each man was breathing air that had previously been in someone else's lungs at least 90 times and the atmosphere quickly grew foul. The sailors knew the air was getting bad when they had trouble lighting their cigarettes. The only solution was to hit the surface and replenish the boat with fresh air. But if the enemy was around, the gasping mariners would just have to suck it up.There was little water available for the kitchen or for showering, and laundry was out of the question. Submariners developed a unique smell - a combination of diesel fuel, sweat, cigarettes, hydraulic fluid, cooking, and sewage. When crew went on shore their uniforms smelt of their sub and on returning home many a wife made hubby strip off outside before being allowed in the house.World War I submarines - the infamous 'pig boats' - had even more primitive ventilation and their steamy recesses bred a rancid funk. Seawater ran across floors, mould and mildew crawled the walls and waves of large cockroaches, and rats, assaulted the kitchen. I've worked in a few dives but nothing even close to that.The submarine cook's tour-of-duty started in port loading out for a two to three month deployment. Supplies had to be put . . . somewhere. The floors of the main deck and corridors were covered with tins and plywood sheet walkways laid on top. Salamis and hams hung in the cramped sleeping quarters, sacks of potatoes were moulded around equipment and men shared their bunks with food. Tins, being totally sealed, filled the bilges and boxes of food were stashed in the showers, the engine room and in escape hatches until there was space to fit it all.Outside of combat situations, a third of the crew was always working, so as well as breakfast, lunch and dinner there was a midnight meal - usually a combination of leftovers and something cooked special. With time and space at a premium the men were lucky to get 10 minutes to eat, as the boat's three shifts all had to pass through the tiny galley. Consequently the cooks kept long hours, were frequently under-staffed and were usually exhausted. Poor bastards.When the boat was rolling 50 or 60 degrees no-one wanted to eat much more than sandwiches, cold cuts or soup. In such conditions the men crumbled crackers or bread into their mugs of soup to give it stability. In long missions across the Pacific, Atlantic or Indian Oceans, the fresh food would run out pretty quick. Milk, butter, meat, eggs, fruit and easily perishable veggies were consumed within a week or two. After a few more weeks, there were no more real potatoes, pumpkins or vegetables. Eggs were coated with Vaseline or grease to limit oxidation and these might last into the second month. Any frozen meat became freezer burnt.Now it became slim pickings and everything came out of a can. Salty rolls of chicken and turkey. Dense solid fists of ravioli. Spam. Nasty powdered milk and eggs. Spam. European submariners were reduced to wurst style sausage, canned cheese and soya-bean filler. Fresh bread and pastry could still be baked, but only when the boat was on the surface. Baking in a submarine was something important and cooks had to be good at it. Fresh rolls, loaves and pies played a strong role in maintaining the positive morale of the crew. The tantalising smells would also momentarily mask the awful submarine pong.By the last month every trick in the book, and some not in it, were used to make the remaining tinned crap palatable. Detailed portion-controlled Navy menus became obsolete. Passing fishing boats would be tapped for some of their catch, and cooks would scavenge the whole boat for any over-looked stashes of ingredients.Worst of all, in the closed atmosphere and industrial environment of a submarine, the constant smell of diesel fuel and hydraulic oil permeated the taste-buds. By the end of the patrol all food tasted like you'd licked the engine room walls. Consequently the number one thing submariners wanted when they finally sailed into port wasn't sex or grog - but a big glass or three of fresh milk. Even the most grizzled old sea-dog would stand in line for that. Running a close second was a crunchy apple or juicy orange - something that wasn't re-hydrated, canned, or tasting of submarine. There was one upside, though. Because of the dangerous and gruelling nature of submarine duty, most navies ensured that submariners got the best food in the fleet. For the first month anyway.In such extreme and hellish conditions, devoid of all creature comforts, it's not surprising that a good submarine cook was a VIP, maybe as important as the skipper himself. Captains busted a gut to get a good one and did almost anything to keep him on board. In the midst of war and death, the power of food, as sustenance, as pleasure and as uplifting memory is hugely amplified. It becomes one of the most important and anticipated things in a potentially short life. One veteran spoke for all submariners. “ A good cook can make up for almost every shitty thing that can happen on a sub, but a lousy one can break a good boat and its crew.”

I've worked in some sweat boxes - kitchens as moist and stinky as a wrestler's jock strap, but for true hard-core cooking action there can't have been much tougher than a wartime submarine's galley. From the primitive subs of the Great War, through to the ocean-going fleets of the Second World War, the deep-water cook worked in a world of monstrous adversity. In tiny kitchens like metal cells, these culinary heroes dealt with botheration incomprehensible to us pampered landlubbers today. Just cooking was a challenge. Submarines frequently travelled on the surface and rough seas would turn hot oil and full pots into skin stripping hazards. This bad weather also meant holding on with one hand while trying to prep and cook with the other. The lack of space left little room to move in the kitchen if there was an accident. Sea water and condensation sometimes dripped from overhead and the grinding 40 degree heat produced by a diesel powered steel tube full of sweating men left the bare-chested cooks dizzy on their feet. And of course – there was an ever-present fear of attack. Day after day loomed the very real possibility of the boat's hull being cracked open by enemy bombs or torpedoes, allowing tons of crushing water to pour in and send the screaming crew on a doomed trip to the ocean floor. At over a 100 metres under the sea the most basic conditions for human survival couldn't be taken for granted. On those submarines each man was breathing air that had previously been in someone else's lungs at least 90 times and the atmosphere quickly grew foul. The sailors knew the air was getting bad when they had trouble lighting their cigarettes. The only solution was to hit the surface and replenish the boat with fresh air. But if the enemy was around, the gasping mariners would just have to suck it up.There was little water available for the kitchen or for showering, and laundry was out of the question. Submariners developed a unique smell - a combination of diesel fuel, sweat, cigarettes, hydraulic fluid, cooking, and sewage. When crew went on shore their uniforms smelt of their sub and on returning home many a wife made hubby strip off outside before being allowed in the house.World War I submarines - the infamous 'pig boats' - had even more primitive ventilation and their steamy recesses bred a rancid funk. Seawater ran across floors, mould and mildew crawled the walls and waves of large cockroaches, and rats, assaulted the kitchen. I've worked in a few dives but nothing even close to that.The submarine cook's tour-of-duty started in port loading out for a two to three month deployment. Supplies had to be put . . . somewhere. The floors of the main deck and corridors were covered with tins and plywood sheet walkways laid on top. Salamis and hams hung in the cramped sleeping quarters, sacks of potatoes were moulded around equipment and men shared their bunks with food. Tins, being totally sealed, filled the bilges and boxes of food were stashed in the showers, the engine room and in escape hatches until there was space to fit it all.Outside of combat situations, a third of the crew was always working, so as well as breakfast, lunch and dinner there was a midnight meal - usually a combination of leftovers and something cooked special. With time and space at a premium the men were lucky to get 10 minutes to eat, as the boat's three shifts all had to pass through the tiny galley. Consequently the cooks kept long hours, were frequently under-staffed and were usually exhausted. Poor bastards.When the boat was rolling 50 or 60 degrees no-one wanted to eat much more than sandwiches, cold cuts or soup. In such conditions the men crumbled crackers or bread into their mugs of soup to give it stability. In long missions across the Pacific, Atlantic or Indian Oceans, the fresh food would run out pretty quick. Milk, butter, meat, eggs, fruit and easily perishable veggies were consumed within a week or two. After a few more weeks, there were no more real potatoes, pumpkins or vegetables. Eggs were coated with Vaseline or grease to limit oxidation and these might last into the second month. Any frozen meat became freezer burnt.Now it became slim pickings and everything came out of a can. Salty rolls of chicken and turkey. Dense solid fists of ravioli. Spam. Nasty powdered milk and eggs. Spam. European submariners were reduced to wurst style sausage, canned cheese and soya-bean filler. Fresh bread and pastry could still be baked, but only when the boat was on the surface. Baking in a submarine was something important and cooks had to be good at it. Fresh rolls, loaves and pies played a strong role in maintaining the positive morale of the crew. The tantalising smells would also momentarily mask the awful submarine pong.By the last month every trick in the book, and some not in it, were used to make the remaining tinned crap palatable. Detailed portion-controlled Navy menus became obsolete. Passing fishing boats would be tapped for some of their catch, and cooks would scavenge the whole boat for any over-looked stashes of ingredients.Worst of all, in the closed atmosphere and industrial environment of a submarine, the constant smell of diesel fuel and hydraulic oil permeated the taste-buds. By the end of the patrol all food tasted like you'd licked the engine room walls. Consequently the number one thing submariners wanted when they finally sailed into port wasn't sex or grog - but a big glass or three of fresh milk. Even the most grizzled old sea-dog would stand in line for that. Running a close second was a crunchy apple or juicy orange - something that wasn't re-hydrated, canned, or tasting of submarine. There was one upside, though. Because of the dangerous and gruelling nature of submarine duty, most navies ensured that submariners got the best food in the fleet. For the first month anyway.In such extreme and hellish conditions, devoid of all creature comforts, it's not surprising that a good submarine cook was a VIP, maybe as important as the skipper himself. Captains busted a gut to get a good one and did almost anything to keep him on board. In the midst of war and death, the power of food, as sustenance, as pleasure and as uplifting memory is hugely amplified. It becomes one of the most important and anticipated things in a potentially short life. One veteran spoke for all submariners. “ A good cook can make up for almost every shitty thing that can happen on a sub, but a lousy one can break a good boat and its crew.”

Published on May 30, 2020 19:53

January 31, 2020

Chefs of Tommorrow

Apprentices are generally young, hung-over and over-sexed. I should know. So over the years, working with these budding chefs of tomorrow, I was never one for calling the kettle black. Their lack of sleep and battering of livers and genitalia was not for me to judge or comment on. But only as long as they came to work, on time, and did their job well. As I did. To be sure, not all apprentices are students of debauchery, but they generally fall into two categories – good and bad. Like in any industry, techniques can be taught and proficiency nurtured, but it always boils down to one thing. Do they care? It's not too hard to tell. Good apprentices listen like thieves and ask questions like cops. Words like anticipate and initiate are not conceptual verbs to them, but crucial mental tasks to be constantly acted on - and quickly too. They rapidly find a way to live with the eternal crux of commercial cooking - the need for speed vs being kinky for quality. Most of all they love and respect food. Bad apprentices usually drop out fairly quickly, or grimly hang in there and become . . . bad chefs. In rare cases their indifference can turn to enthusiasm as a result of your patient encouragement. You'll feel like Robin Williams in the Good Will Poets Society when this happens. However, in trying to achieve such miracles it's incumbent upon you not to be a bastard. Correcting, directing and cajoling apprentices is legit, but to hassle them for anything else outside of the quest for speed or quality is just rotten power mongering. Shamefully, I have at times been a little dictatorial. I worked with a cheery young apprentice who spent a good percentage of his shift being affably empathetic. Like a cosmic butterfly he fluttered around solving people's emotional problems and showering us with fairy dust mined from his ever loving soul. After one day too many of this compassionate bludging I reviewed his output and forcefully explained that rust was quicker than he was. Bursting into tears he ran from the kitchen. Prompted by the owner, I coaxed him back and was gratified to see him curtail the new-age charity and do some old-school work. On another occasion I mimicked the snail's gait of a dreamy and impossibly slow apprentice. As everyone cracked up, this normally docile fellow exploded, stamping in rage and shouting at me. It was like a sloth suddenly doing Kung Fu. Remembering what they say about the quiet ones, I took a few steps back, calmed him down with an apology and he shuffled off. Asking an apprentice to do an unpalatable job requires force of character and for them to respect your knowledge. Those two things, and the kitchen uniforms and traditions, generally impel them to get on with it. But the senior/junior dynamic is definitely open to abuse. The full gamut of abuse - physical, sexual, mental and emotional has been the apprentice's lot. Often disguised as a joke or a prank that essential wrong is there. In one London kitchen I worked in, the overweight buffoon of a Sous Chef was a jealous power tripper. He started calling a well-liked apprentice 'Dickhead' - initially as a muttered aside. When he did this in front of the busily prepping crew one morning, the sturdy youngster immediately called him on it. Everyone turned to look and from their narrowed eyes and serious frowns it was easy to see with whom their sympathies lay. “It was just a joke,” backpedaled the Sous. “Just being funny." “Oh OK Phatphuk,” replied the apprentice brightly. Our howls of laughter sent the deflated bully on an impromptu cigarette break. As a newbie starting out I was fortunate not to have suffered any persecution, but others of my generation were not so lucky. I've seen a scar on a chef's hand where as an apprentice a chef 'jokingly' pretended to cut him and 'missed'. Another colleague recalled being grabbed hard by the ear and painfully dragged into a cold room to be shown that it wasn't as clean as it should be. Yet another chef recalled the Sous Chef who screamed so loudly at an apprentice that the poor kid wet himself. This is how fascism starts. After a year into their three or four year culinary education, apprentices get their own title - Commis Chef - which I actually can't recall anyone using. More likely they'll be referred to by the year they're in - as in “Tell the second year to grab some more lamb,” or “Where did that first year get to?”In big kitchens, apprentices can focus on cooking, guided by a Chef de Partie (a head of a section) learning the prep and service of the section. At shift's end they clean up nothing more than their area. In small kitchens apprentices do the kitchen hand work, bringing in stores, cleaning the kitchen, sweeping and mopping floors. You can tell who has come up this way as they work clean. The very best apprentices are the ones who have the skills to step in and save your arse. On an island resort on the Great Barrier Reef our apprentice Mikey was a super-star. He quickly mastered the breakfast and lunch shifts and was soon working solo. His star shone even brighter the day I accidentally became a bit incapacitated. I had two days off on the mainland and on the night before my return I was stoned and drunk with friends at a dance party. A bowler-hatted lady sold me her last tab of somewhat expensive acid. I washed down the rather large piece of blotter with my umpteenth beer reasoning that it would wear off by the time I'd caught the boat back to work the next morning. Mikey was kindly filling in for my breakfast shift, and though sure to be hung-over, I'd shower, don my whites and still pull off a splendid lunch for the guests. I was dancing when the lysergic rush hit and it was strong. Really strong. The bowler hat lady appeared and yelled in my ear. “How are you and your friends enjoying it?” “Friends? What do you mean friends?” I said. “That was for four people!” she said. Hendix on a Saturn V rocket! Four hits of acid! I had to act fast as a Category Five psychedelic storm was blowing away all logic and understanding. I explained to a friend what I'd just done and he agreed to get me on the once-a-day boat back to the island come morning. Then I found a pay phone and with growing difficulty called the resort. Sure enough, Mikey was at the bar with other staff having a few drinks - the guests all long gone to bed. I burbled down the line to him. Could he do my lunch shift? No problem at all he said, but why? When I explained he screamed with laughter and broadcast my state of mind to the bar. Down the line a huge cheer rang out and Mikey, with the crew in the background, exhorted me to party hard all night long. And oh yeah - he'd be expecting a full report of my night's festivities over drinks when he finished work tomorrow. Now that's a great apprentice!

Apprentices are generally young, hung-over and over-sexed. I should know. So over the years, working with these budding chefs of tomorrow, I was never one for calling the kettle black. Their lack of sleep and battering of livers and genitalia was not for me to judge or comment on. But only as long as they came to work, on time, and did their job well. As I did. To be sure, not all apprentices are students of debauchery, but they generally fall into two categories – good and bad. Like in any industry, techniques can be taught and proficiency nurtured, but it always boils down to one thing. Do they care? It's not too hard to tell. Good apprentices listen like thieves and ask questions like cops. Words like anticipate and initiate are not conceptual verbs to them, but crucial mental tasks to be constantly acted on - and quickly too. They rapidly find a way to live with the eternal crux of commercial cooking - the need for speed vs being kinky for quality. Most of all they love and respect food. Bad apprentices usually drop out fairly quickly, or grimly hang in there and become . . . bad chefs. In rare cases their indifference can turn to enthusiasm as a result of your patient encouragement. You'll feel like Robin Williams in the Good Will Poets Society when this happens. However, in trying to achieve such miracles it's incumbent upon you not to be a bastard. Correcting, directing and cajoling apprentices is legit, but to hassle them for anything else outside of the quest for speed or quality is just rotten power mongering. Shamefully, I have at times been a little dictatorial. I worked with a cheery young apprentice who spent a good percentage of his shift being affably empathetic. Like a cosmic butterfly he fluttered around solving people's emotional problems and showering us with fairy dust mined from his ever loving soul. After one day too many of this compassionate bludging I reviewed his output and forcefully explained that rust was quicker than he was. Bursting into tears he ran from the kitchen. Prompted by the owner, I coaxed him back and was gratified to see him curtail the new-age charity and do some old-school work. On another occasion I mimicked the snail's gait of a dreamy and impossibly slow apprentice. As everyone cracked up, this normally docile fellow exploded, stamping in rage and shouting at me. It was like a sloth suddenly doing Kung Fu. Remembering what they say about the quiet ones, I took a few steps back, calmed him down with an apology and he shuffled off. Asking an apprentice to do an unpalatable job requires force of character and for them to respect your knowledge. Those two things, and the kitchen uniforms and traditions, generally impel them to get on with it. But the senior/junior dynamic is definitely open to abuse. The full gamut of abuse - physical, sexual, mental and emotional has been the apprentice's lot. Often disguised as a joke or a prank that essential wrong is there. In one London kitchen I worked in, the overweight buffoon of a Sous Chef was a jealous power tripper. He started calling a well-liked apprentice 'Dickhead' - initially as a muttered aside. When he did this in front of the busily prepping crew one morning, the sturdy youngster immediately called him on it. Everyone turned to look and from their narrowed eyes and serious frowns it was easy to see with whom their sympathies lay. “It was just a joke,” backpedaled the Sous. “Just being funny." “Oh OK Phatphuk,” replied the apprentice brightly. Our howls of laughter sent the deflated bully on an impromptu cigarette break. As a newbie starting out I was fortunate not to have suffered any persecution, but others of my generation were not so lucky. I've seen a scar on a chef's hand where as an apprentice a chef 'jokingly' pretended to cut him and 'missed'. Another colleague recalled being grabbed hard by the ear and painfully dragged into a cold room to be shown that it wasn't as clean as it should be. Yet another chef recalled the Sous Chef who screamed so loudly at an apprentice that the poor kid wet himself. This is how fascism starts. After a year into their three or four year culinary education, apprentices get their own title - Commis Chef - which I actually can't recall anyone using. More likely they'll be referred to by the year they're in - as in “Tell the second year to grab some more lamb,” or “Where did that first year get to?”In big kitchens, apprentices can focus on cooking, guided by a Chef de Partie (a head of a section) learning the prep and service of the section. At shift's end they clean up nothing more than their area. In small kitchens apprentices do the kitchen hand work, bringing in stores, cleaning the kitchen, sweeping and mopping floors. You can tell who has come up this way as they work clean. The very best apprentices are the ones who have the skills to step in and save your arse. On an island resort on the Great Barrier Reef our apprentice Mikey was a super-star. He quickly mastered the breakfast and lunch shifts and was soon working solo. His star shone even brighter the day I accidentally became a bit incapacitated. I had two days off on the mainland and on the night before my return I was stoned and drunk with friends at a dance party. A bowler-hatted lady sold me her last tab of somewhat expensive acid. I washed down the rather large piece of blotter with my umpteenth beer reasoning that it would wear off by the time I'd caught the boat back to work the next morning. Mikey was kindly filling in for my breakfast shift, and though sure to be hung-over, I'd shower, don my whites and still pull off a splendid lunch for the guests. I was dancing when the lysergic rush hit and it was strong. Really strong. The bowler hat lady appeared and yelled in my ear. “How are you and your friends enjoying it?” “Friends? What do you mean friends?” I said. “That was for four people!” she said. Hendix on a Saturn V rocket! Four hits of acid! I had to act fast as a Category Five psychedelic storm was blowing away all logic and understanding. I explained to a friend what I'd just done and he agreed to get me on the once-a-day boat back to the island come morning. Then I found a pay phone and with growing difficulty called the resort. Sure enough, Mikey was at the bar with other staff having a few drinks - the guests all long gone to bed. I burbled down the line to him. Could he do my lunch shift? No problem at all he said, but why? When I explained he screamed with laughter and broadcast my state of mind to the bar. Down the line a huge cheer rang out and Mikey, with the crew in the background, exhorted me to party hard all night long. And oh yeah - he'd be expecting a full report of my night's festivities over drinks when he finished work tomorrow. Now that's a great apprentice!

Published on January 31, 2020 17:55

January 7, 2020

Amuse-bouche

Amuse-bouche are complimentary bite-sized serves of finger food to amuse the mouth before starting on the menu. Here are some tasty little morsels for your optical entertainment.Mistaken identityNaughty but niceTeamworkFlaming betel paan!!Souma's ultra-intense animie food battleWizard of Floss

Amuse-bouche are complimentary bite-sized serves of finger food to amuse the mouth before starting on the menu. Here are some tasty little morsels for your optical entertainment.Mistaken identityNaughty but niceTeamworkFlaming betel paan!!Souma's ultra-intense animie food battleWizard of Floss

Published on January 07, 2020 23:48

December 11, 2019

The Q Word

It’s a new café in your manor; you feel like supporting it with your custom and you order something simple - a slice of ham and cheese quiche with a garden salad. It’s not just altruism– you’re hungry too, but when the food arrives and you begin to eat, any sense of the philanthropic evaporates real damn quick.See, the quiche is crap, the pastry overworked and tough. There’s too much egg in the mix; giving it the consistency of the painted rubber tofu made for restaurant-window displays. Flakes of dandruff would have more bite than the cheddar cheese used, and the ham is processed rubbish – uber-salty cubes the colour of dead Barbie dolls. A very frugal hand has added seasoning and the little flecks of herbs are of the dried, old-cut-grass variety.Equally devoid of merit is the salad. It comprises an indifferently mounted display of near-white iceberg lettuce leaves hacked into submission, slices of sleepy, watery tomato sporting black spots but no flavour, and fridge-dried slices of cucumber and onion. The dressing on this failed tuck-shop fantasia is so bland that you wonder if the cook ever passed the acid test. The meal is technically edible, but only just.OK, let’s rewind. You pop into the new café on the block keen to support their fledgling endeavor and when you order a piece of ham and cheese quiche with a garden salad and start eating - mmmwwahh! – you know you’re in for a treat.The properly short pastry is the work of an alchemist; pure culinary gold just melting in your mouth. The filling is as light and fluffy as angel’s kisses, and seasoned just so. The ham is off the bone, each little piece a pearl of smokey flavor. The herbs in the filling are fresh and there’s a herb sprig as a garnish to demonstrate this fact. This isn’t quiche – it’s a wedge of heaven.The salad; a colorful, comely thing, looks good enough to eat – and it is. Crisp garden greens, constellations of bean sprouts and toasted seeds, luscious, blemish-free tomatoes and fresh shavings of red onion and fennel romp in this sangfroid orgy. And everything is bedewed with a nirvanic mist – a citrus spiked dressing possessing the perfect bite. This lunch is not just edible – it's flawless.Bless the cook who has made this meal, for they understand quality. The ingredients: fresh salad fixings, decent ham; even the crunchy surprise of toasted seeds are the first part of what defines quality. That the cook can make proper pastry and salad dressing, understands what a quiche filling really is, and knows not to use less than fresh salad makings is the second. Last but not least is the attitude of the cook. Training and experience are essential but it's not just the doing – it’s getting off on the doing, that elevates a meal into the realms of good quality.Quality, at the very least, means that your meal should resemble in every sensory way what the menu says it is, and then in a very personal way, it should also fulfill your expectations. It’s a tricky thing, a balancing act, but quality must satisfy these stated and implied needs.For the diner, the key to understanding quality is experience and knowledge – as in eating out lots, whether at restaurants, food markets and bistros, or at the homes of friends and relatives who love to cook and eat. It ain’t abstruse. You can grasp, and understand, quality with the repeatedly experiencing it. And what’s really cool is that this appreciation requires zero thinking or intellectualizing. Until you talk about it that is. So it’s imperative for culinary industry professionals, both front-of-house and in the kitchen, to eat out and be customers. These pros must check out what’s going down (throats) in their town or city. I was once part of an informal club of catering waiters and chefs all lucky enough to get nights off sometimes, and keen to deepen our relationship with quality. New, high-end eating establishments were our usual destination, with the occasional well-mooted bistro or café thrown in.Convening over aperitifs, cocktails and nibbles here, we’d go and have the main event with selected wines there, then move elsewhere for dessert and liqueurs, sometimes kicking on to a specialty bar for a session with assorted varieties and preparations of one particular drink. It was not uncommon for us to spend $150 a head, or $240 in today’s money. Sadly, we couldn’t claim all this eating out as research, but the sheer pleasure of sharing exquisite food and drink with fellow explorers, and learning about quality, was totally worth it.

It’s a new café in your manor; you feel like supporting it with your custom and you order something simple - a slice of ham and cheese quiche with a garden salad. It’s not just altruism– you’re hungry too, but when the food arrives and you begin to eat, any sense of the philanthropic evaporates real damn quick.See, the quiche is crap, the pastry overworked and tough. There’s too much egg in the mix; giving it the consistency of the painted rubber tofu made for restaurant-window displays. Flakes of dandruff would have more bite than the cheddar cheese used, and the ham is processed rubbish – uber-salty cubes the colour of dead Barbie dolls. A very frugal hand has added seasoning and the little flecks of herbs are of the dried, old-cut-grass variety.Equally devoid of merit is the salad. It comprises an indifferently mounted display of near-white iceberg lettuce leaves hacked into submission, slices of sleepy, watery tomato sporting black spots but no flavour, and fridge-dried slices of cucumber and onion. The dressing on this failed tuck-shop fantasia is so bland that you wonder if the cook ever passed the acid test. The meal is technically edible, but only just.OK, let’s rewind. You pop into the new café on the block keen to support their fledgling endeavor and when you order a piece of ham and cheese quiche with a garden salad and start eating - mmmwwahh! – you know you’re in for a treat.The properly short pastry is the work of an alchemist; pure culinary gold just melting in your mouth. The filling is as light and fluffy as angel’s kisses, and seasoned just so. The ham is off the bone, each little piece a pearl of smokey flavor. The herbs in the filling are fresh and there’s a herb sprig as a garnish to demonstrate this fact. This isn’t quiche – it’s a wedge of heaven.The salad; a colorful, comely thing, looks good enough to eat – and it is. Crisp garden greens, constellations of bean sprouts and toasted seeds, luscious, blemish-free tomatoes and fresh shavings of red onion and fennel romp in this sangfroid orgy. And everything is bedewed with a nirvanic mist – a citrus spiked dressing possessing the perfect bite. This lunch is not just edible – it's flawless.Bless the cook who has made this meal, for they understand quality. The ingredients: fresh salad fixings, decent ham; even the crunchy surprise of toasted seeds are the first part of what defines quality. That the cook can make proper pastry and salad dressing, understands what a quiche filling really is, and knows not to use less than fresh salad makings is the second. Last but not least is the attitude of the cook. Training and experience are essential but it's not just the doing – it’s getting off on the doing, that elevates a meal into the realms of good quality.Quality, at the very least, means that your meal should resemble in every sensory way what the menu says it is, and then in a very personal way, it should also fulfill your expectations. It’s a tricky thing, a balancing act, but quality must satisfy these stated and implied needs.For the diner, the key to understanding quality is experience and knowledge – as in eating out lots, whether at restaurants, food markets and bistros, or at the homes of friends and relatives who love to cook and eat. It ain’t abstruse. You can grasp, and understand, quality with the repeatedly experiencing it. And what’s really cool is that this appreciation requires zero thinking or intellectualizing. Until you talk about it that is. So it’s imperative for culinary industry professionals, both front-of-house and in the kitchen, to eat out and be customers. These pros must check out what’s going down (throats) in their town or city. I was once part of an informal club of catering waiters and chefs all lucky enough to get nights off sometimes, and keen to deepen our relationship with quality. New, high-end eating establishments were our usual destination, with the occasional well-mooted bistro or café thrown in.Convening over aperitifs, cocktails and nibbles here, we’d go and have the main event with selected wines there, then move elsewhere for dessert and liqueurs, sometimes kicking on to a specialty bar for a session with assorted varieties and preparations of one particular drink. It was not uncommon for us to spend $150 a head, or $240 in today’s money. Sadly, we couldn’t claim all this eating out as research, but the sheer pleasure of sharing exquisite food and drink with fellow explorers, and learning about quality, was totally worth it.

Published on December 11, 2019 00:48

November 14, 2019

Customers

It’s the biggest horse-race of the year and we’re cooking in a track-side marquee. Well-dressed, drunken men barge in and start cutting up lines of white powder on a work-bench. Another urinates on the ground next to boxes of cutlery and food. They yell and swear when told to leave. We aim a fire hose at the intruders and a half-full wine bottle flies through the air and explodes against an oven.Drunk and obstreperous, he’s short the price of his takeaway spaghetti marinara. He and the server have an antagonistic history and he hurls the skin-scorching hot meal at his nemesis. The server ducks. Splat! Prawns and pasta fly; the rest of the meal slides down the wall in a snails-trail of cream.Arriving half an hour after the kitchen’s close she wants a steak. Now. Front-of-house decline her request and she grabs the till, tears it loose and throws it to crash open on the floor. Fortunately, this sort of awful behaviour is rare and thank god, because the great unfed; the general public are what it’s all about. Contrary to the opinions of some chefs and owners, customers are the most important people in the restaurant. Without them we are nothing.'The customer is always right,' is a basic tenet of hospitality, but unscrupulous diners will use it to their advantage. Like the green young waitress telling me a customer needed his dozen oysters replaced, at no extra charge, because they were off. Calling bullshit, I ask to see them. Oh, but he’s eaten them all. Trying to scam a meal is one thing, but a whole table of food is another level of larceny. During a manic lunch service, jam-packed with fast turnovers of tables, a family of six, eating a substantial lunch, suddenly freak out.The daughter, allergic to peanuts, has eaten sauce containing them and is in anaphylactic shock. Front of house deal with this emergency, using an epidermal pen on the . . . relaxed and subdued teen. Dad, aggressively loud, insists the restaurant call an ambulance and the family all leave with the paramedics. Without paying.An hour later Dad rings up. He wants to sue the restaurant. The owner explains that the menu stated all the ingredients clearly – and no-one mentioned any allergies. Dad insists that a legal assault will be made. The owner sticks to his guns. Then Dad says he is open to an out-of-court settlement. “Bring it on,” laughs the owner. We never hear from this shake-down artist again. Sadly, there sometimes is such a thing as a free lunch – in this case entrees and mains for six.Sometimes the customer is wrong. Yes, ma’am I’ve been to Bali too, but gado gado has no meat in it. No sir, the Guinness pie is not served with a pint of Irish stout on the side. We shouldn’t laugh at their ignorance either, but sometimes it’s hard. How about being sternly told to hold the canine pepper on the grilled fish?Or the cocktail party guest inquiring about the tiny buns, perfect replicas of a high-top loaf, stuffed with rare roast beef and rocket. Did we use very small ovens to bake these loaves? Yes, and the chefs are 16 cm tall.And comes that day when the customer makes an error that taxes morality and tests one’s ethics. I was working at an open-kitchen bistro in the off-season. Mondays were dead, and I worked them alone; taking orders, serving, making drinks, cooking, cleaning up and balancing the till at the end of the day.One afternoon a well-dressed, elderly Japanese man had lunch with his wife. He had no English but indicated what he wanted. They happily ate and drank and when it came time to pay, the man peered at the bill; a total of $32. He began peeling off twenties and fifties and laying them on the counter. I was taken aback. The old geezer thought the bill was three hundred and twenty dollars! A voice from the dark side whispered in my ear, “Go on, take it. No one will know.”But I'm not made that way and I gestured at the man to stop counting out notes. He looked at me in surprise, and I carefully removed two twenties, showed them to him, and made the change. The rest of the money I politely indicated wasn't necessary. Realisation dawned in his eyes. I got a sincere nod of thanks and he gathered up the pile of notes and put them back in his wallet.Customers do consciously give cooks money though, even coming into the kitchen to do so. I’ve had currency notes thrust into my hand in the middle of service by happy customers.Being giving money is great, but any compliment really does make a line-cook’s day. Truly folks, your positive acknowledgement of the grunts in the kitchen cannot be underestimated. It turns the headache of a difficult service, or frustration over an earlier cock-up, into good cheer and warranted pride. This sort of five-second altruism will melt a hard old cook’s heart.The customers who create a really special glow are the regulars. They become family as they return again and again like kids to Mum’s bosom. We hear their stories and they hear ours. The food we make becomes a part of their lives and they become part of ours. We love them as they vindicate our culinary prowess and our love and care. In a world of fast-moving trends and shifting demographics these loyal diners can justify our very existence.So, the coldest chill a cook can feel, the darkest depth to which they can fall — is when a regular makes a negative comment about their food. Watch the cook rush out front, face creased with concern, to engage with their customer. See them listen beetle-browed and intent and then forensically dissect exactly wasn’t right. The cook will personally remove the offending plate and take it away.And as they rush back to make the meal again, perfectly this time, they might stop by the till and insist on paying for their customers meal. Now ain’t that close to love?

It’s the biggest horse-race of the year and we’re cooking in a track-side marquee. Well-dressed, drunken men barge in and start cutting up lines of white powder on a work-bench. Another urinates on the ground next to boxes of cutlery and food. They yell and swear when told to leave. We aim a fire hose at the intruders and a half-full wine bottle flies through the air and explodes against an oven.Drunk and obstreperous, he’s short the price of his takeaway spaghetti marinara. He and the server have an antagonistic history and he hurls the skin-scorching hot meal at his nemesis. The server ducks. Splat! Prawns and pasta fly; the rest of the meal slides down the wall in a snails-trail of cream.Arriving half an hour after the kitchen’s close she wants a steak. Now. Front-of-house decline her request and she grabs the till, tears it loose and throws it to crash open on the floor. Fortunately, this sort of awful behaviour is rare and thank god, because the great unfed; the general public are what it’s all about. Contrary to the opinions of some chefs and owners, customers are the most important people in the restaurant. Without them we are nothing.'The customer is always right,' is a basic tenet of hospitality, but unscrupulous diners will use it to their advantage. Like the green young waitress telling me a customer needed his dozen oysters replaced, at no extra charge, because they were off. Calling bullshit, I ask to see them. Oh, but he’s eaten them all. Trying to scam a meal is one thing, but a whole table of food is another level of larceny. During a manic lunch service, jam-packed with fast turnovers of tables, a family of six, eating a substantial lunch, suddenly freak out.The daughter, allergic to peanuts, has eaten sauce containing them and is in anaphylactic shock. Front of house deal with this emergency, using an epidermal pen on the . . . relaxed and subdued teen. Dad, aggressively loud, insists the restaurant call an ambulance and the family all leave with the paramedics. Without paying.An hour later Dad rings up. He wants to sue the restaurant. The owner explains that the menu stated all the ingredients clearly – and no-one mentioned any allergies. Dad insists that a legal assault will be made. The owner sticks to his guns. Then Dad says he is open to an out-of-court settlement. “Bring it on,” laughs the owner. We never hear from this shake-down artist again. Sadly, there sometimes is such a thing as a free lunch – in this case entrees and mains for six.Sometimes the customer is wrong. Yes, ma’am I’ve been to Bali too, but gado gado has no meat in it. No sir, the Guinness pie is not served with a pint of Irish stout on the side. We shouldn’t laugh at their ignorance either, but sometimes it’s hard. How about being sternly told to hold the canine pepper on the grilled fish?Or the cocktail party guest inquiring about the tiny buns, perfect replicas of a high-top loaf, stuffed with rare roast beef and rocket. Did we use very small ovens to bake these loaves? Yes, and the chefs are 16 cm tall.And comes that day when the customer makes an error that taxes morality and tests one’s ethics. I was working at an open-kitchen bistro in the off-season. Mondays were dead, and I worked them alone; taking orders, serving, making drinks, cooking, cleaning up and balancing the till at the end of the day.One afternoon a well-dressed, elderly Japanese man had lunch with his wife. He had no English but indicated what he wanted. They happily ate and drank and when it came time to pay, the man peered at the bill; a total of $32. He began peeling off twenties and fifties and laying them on the counter. I was taken aback. The old geezer thought the bill was three hundred and twenty dollars! A voice from the dark side whispered in my ear, “Go on, take it. No one will know.”But I'm not made that way and I gestured at the man to stop counting out notes. He looked at me in surprise, and I carefully removed two twenties, showed them to him, and made the change. The rest of the money I politely indicated wasn't necessary. Realisation dawned in his eyes. I got a sincere nod of thanks and he gathered up the pile of notes and put them back in his wallet.Customers do consciously give cooks money though, even coming into the kitchen to do so. I’ve had currency notes thrust into my hand in the middle of service by happy customers.Being giving money is great, but any compliment really does make a line-cook’s day. Truly folks, your positive acknowledgement of the grunts in the kitchen cannot be underestimated. It turns the headache of a difficult service, or frustration over an earlier cock-up, into good cheer and warranted pride. This sort of five-second altruism will melt a hard old cook’s heart.The customers who create a really special glow are the regulars. They become family as they return again and again like kids to Mum’s bosom. We hear their stories and they hear ours. The food we make becomes a part of their lives and they become part of ours. We love them as they vindicate our culinary prowess and our love and care. In a world of fast-moving trends and shifting demographics these loyal diners can justify our very existence.So, the coldest chill a cook can feel, the darkest depth to which they can fall — is when a regular makes a negative comment about their food. Watch the cook rush out front, face creased with concern, to engage with their customer. See them listen beetle-browed and intent and then forensically dissect exactly wasn’t right. The cook will personally remove the offending plate and take it away.And as they rush back to make the meal again, perfectly this time, they might stop by the till and insist on paying for their customers meal. Now ain’t that close to love?

Published on November 14, 2019 03:47

October 17, 2019

Mercenary Story

It didn’t get more mercenary than this. On the horizon - 3 billion dollars worth of marine hardware.Behind me - a gargantuan industrial complex that moved 9 billion dollars worth of product eachyear. I was cooking for the workers at one of the biggest coal ports in the world. Yeah coal. I was a chef agency knife for hire at that time and not so woke. The five-week gig - fifty hours a week onthe tropical coast, food and accommodation included - had looked real sweet. So I said yes.But on arrival I found out that my working day consisted of just five hours – prepping and cooking for a single dinner service. It took one phone-call to establish that between the agency and the hotel, no-one really could say who, someone had told me a big porky pie. I politely told the hotel manager I was heading back to the airport. He threw up his hands and smiled. No problem - we’ll pay you for fifty hours even if you do twenty five he said. Nice one.I soon found out that money was no object in the unreal world I’d landed in. The hotel was five minutes from the coal port and was fully booked – forever - with port workers, and they were allpaid an extra two hundred bucks a day just for living expenses. So the nightly service consisted of a few dozen knackered men knocking back beer and spirits in the bar, then demolishing oysters, prawns, taters, salads and one, two – even three – eye filet steaks apiece. And dessert. Now sated, they’d go to bed. By eight o’clock the dining room was empty.It was a piece of cake dealing with cases of prime filet and boxes of prawns, roasting bones forjus and cooking potatoes six ways til Sunday. I got my jollies making different salads, sauces and desserts. Prepping in the late afternoon, I looked out onto palm trees, green lawns and beach sunsets. Hibiscuses and frangipanis bloomed and a nearby wetland meant that the birdlife was amazing.It was only when I actually walked down onto the foreshore and looked around that the hugescale of the port became apparent. On the horizon, in a massive armada of global commerce, giant bulk carrier ships awaited their black cargo. On the beach, with giant hammering noises, fabricating workshops made and repaired immense structures for the port. Above the wet-lands foliage loomed black pyramids of coal and immense conveyors that ran 24/7/365.The loading terminal stuck out nearly two kms into the sea and a stone groin ended in a high-security base for pilot-boats. At night I could hear the deep rumble of their diesel engines as they went out to guide the bulkers in. The port projected an intensely serious vibe. It felt like the Death Star. As a major cog in the global economy it made things like sports stadiums, office towers and resort hotels all seem rather superfluous, soft and weak. This was the serious shit and it affected hundreds of millions, maybe billions, of people. The coal port was a major geo-political location; a valuable piece of the planet’s industrial real-estate.In different circumstances I could imagine soldiers here, with tanks, helicopters and attack ships. There was probably a top-secret military plan for when those circumstances happened. I alwayshad the feeling I was being watched whenever I wandered around. Maybe from space.I wasn’t the only person making money off the workers. Hard-working ladies ran laundry services day and night. Younger women in tight clothes, lippy and eyeliner hung at the bar ready to trade some earthly pleasure for a hundred-dollar bill or two. There was a bloke who would turn up witha van full of the latest magazines for sale – the ones about 4WDs, boats and guns being the most popular. He also stocked socks, jocks, ear-plugs, sunglasses, razors, deodorant, shampoo and soap. There were some souped-up cars in the car-park at night and non-workers hanging in the bar too. Maybe certain recreational supplies were being sold and bought.It was a strange place, seemingly detached, by coal and its money, from the rest of the world. I spent my mornings walking around a nearby and super-cute beach hamlet, and bird-watching in the vast wetland lagoons. I wasn’t drinking and at night after work, I’d go back to my accommodation – one half of a shipping container. The hotel had nowhere near enough rooms,so next to it was an acre of air-conditioned containers, many divided into two cabins. Each one was fitted-out with walls, floor, carpet, lights, fridge, basic kitchen, and bed. There were a couple of amenity blocks with showers, toilets and laundries.In my steel lair I could watch TV or read from the stack of battered paperbacks I’d bought in the nearest town. This was pre-smart phones and I resolved myself to late-night TV rubbish and rationing of my books. Then the other chef came to my ‘rescue.’Rod was in his early sixties, ex-army with no wife or kids. Recuperating from a knee operation, he did the ordering and one or two shifts a week while I did the rest. He was OK, just, but sported some incredibly old-school prejudices and beliefs. On my third day there I visited him in his full-size shipping container, where he’d lived for last five years. It was his long-term home, decked-out with Balinese furniture and paintings; Asian rugs and knick-knacks, and a giant TV screen complete with surround sound speakers. On the walls hung replica firearms and framed photos of 22 years life in the army. Over the next few weeks I heard quite a bit about his military life.Rod had also collected several thousand DVDs, and unsurprising, most of them were war-themed. Concerned I might get bored after work, he pressed upon me a spare DVD player, RCA leads and the first of many tall stacks of war movies and documentaries for me to watch. Man, I never knew there were so many battles. I watched The Battle of This and Battle of That and soon it all beganto blur into a series of explosions, stubbled jaws clamped on cigars and crackly radio commands. Some battles went to three discs!As I returned these slices of combat heaven, Rod would seriously quiz me on each theater of war, battle and skirmish I’d watched. Scarcely acknowledging my uneducated, shell-shocked replies, he’d launch into exhaustive dissertations of the tactics, fighting men and weapons portrayed in each film. He also had many theories and ideas about current affairs and potential flash-points. Harping on about its proximity and imperial ambitions, Rod worried about Indonesia the most.One day, barely keeping up with all things military – past, present and future – I asked him whathe thought the plan for the coal port here was. “What plan?” Rod looked puzzled. “Y’know . . . when they invade.”His eyebrows shot up in shock. “This is one of the very first places they’ll come to,” I continued. “I reckon at least two paratroop battalions with armored fighting vehicles, maybe a tank or two. Para-drops of mortars, recoilless rifles and RPGs, plus marines in littoral fast-boats assaulting the beach. Helicopter gunships and ground-attack planes providing air support of course.”Rod reeled and spluttered. “Here?” “Yeah. Wouldn’t you? Major coal port and all.”The absolute strategic rightness of it nearly floored him. Red-faced, he looked around as though the door was about to be blown in.I couldn’t help myself. “You better brush up on your nasi goreng Chef. And get the bar to order in Bintang. Lots of Bintang.”

It didn’t get more mercenary than this. On the horizon - 3 billion dollars worth of marine hardware.Behind me - a gargantuan industrial complex that moved 9 billion dollars worth of product eachyear. I was cooking for the workers at one of the biggest coal ports in the world. Yeah coal. I was a chef agency knife for hire at that time and not so woke. The five-week gig - fifty hours a week onthe tropical coast, food and accommodation included - had looked real sweet. So I said yes.But on arrival I found out that my working day consisted of just five hours – prepping and cooking for a single dinner service. It took one phone-call to establish that between the agency and the hotel, no-one really could say who, someone had told me a big porky pie. I politely told the hotel manager I was heading back to the airport. He threw up his hands and smiled. No problem - we’ll pay you for fifty hours even if you do twenty five he said. Nice one.I soon found out that money was no object in the unreal world I’d landed in. The hotel was five minutes from the coal port and was fully booked – forever - with port workers, and they were allpaid an extra two hundred bucks a day just for living expenses. So the nightly service consisted of a few dozen knackered men knocking back beer and spirits in the bar, then demolishing oysters, prawns, taters, salads and one, two – even three – eye filet steaks apiece. And dessert. Now sated, they’d go to bed. By eight o’clock the dining room was empty.It was a piece of cake dealing with cases of prime filet and boxes of prawns, roasting bones forjus and cooking potatoes six ways til Sunday. I got my jollies making different salads, sauces and desserts. Prepping in the late afternoon, I looked out onto palm trees, green lawns and beach sunsets. Hibiscuses and frangipanis bloomed and a nearby wetland meant that the birdlife was amazing.It was only when I actually walked down onto the foreshore and looked around that the hugescale of the port became apparent. On the horizon, in a massive armada of global commerce, giant bulk carrier ships awaited their black cargo. On the beach, with giant hammering noises, fabricating workshops made and repaired immense structures for the port. Above the wet-lands foliage loomed black pyramids of coal and immense conveyors that ran 24/7/365.The loading terminal stuck out nearly two kms into the sea and a stone groin ended in a high-security base for pilot-boats. At night I could hear the deep rumble of their diesel engines as they went out to guide the bulkers in. The port projected an intensely serious vibe. It felt like the Death Star. As a major cog in the global economy it made things like sports stadiums, office towers and resort hotels all seem rather superfluous, soft and weak. This was the serious shit and it affected hundreds of millions, maybe billions, of people. The coal port was a major geo-political location; a valuable piece of the planet’s industrial real-estate.In different circumstances I could imagine soldiers here, with tanks, helicopters and attack ships. There was probably a top-secret military plan for when those circumstances happened. I alwayshad the feeling I was being watched whenever I wandered around. Maybe from space.I wasn’t the only person making money off the workers. Hard-working ladies ran laundry services day and night. Younger women in tight clothes, lippy and eyeliner hung at the bar ready to trade some earthly pleasure for a hundred-dollar bill or two. There was a bloke who would turn up witha van full of the latest magazines for sale – the ones about 4WDs, boats and guns being the most popular. He also stocked socks, jocks, ear-plugs, sunglasses, razors, deodorant, shampoo and soap. There were some souped-up cars in the car-park at night and non-workers hanging in the bar too. Maybe certain recreational supplies were being sold and bought.It was a strange place, seemingly detached, by coal and its money, from the rest of the world. I spent my mornings walking around a nearby and super-cute beach hamlet, and bird-watching in the vast wetland lagoons. I wasn’t drinking and at night after work, I’d go back to my accommodation – one half of a shipping container. The hotel had nowhere near enough rooms,so next to it was an acre of air-conditioned containers, many divided into two cabins. Each one was fitted-out with walls, floor, carpet, lights, fridge, basic kitchen, and bed. There were a couple of amenity blocks with showers, toilets and laundries.In my steel lair I could watch TV or read from the stack of battered paperbacks I’d bought in the nearest town. This was pre-smart phones and I resolved myself to late-night TV rubbish and rationing of my books. Then the other chef came to my ‘rescue.’Rod was in his early sixties, ex-army with no wife or kids. Recuperating from a knee operation, he did the ordering and one or two shifts a week while I did the rest. He was OK, just, but sported some incredibly old-school prejudices and beliefs. On my third day there I visited him in his full-size shipping container, where he’d lived for last five years. It was his long-term home, decked-out with Balinese furniture and paintings; Asian rugs and knick-knacks, and a giant TV screen complete with surround sound speakers. On the walls hung replica firearms and framed photos of 22 years life in the army. Over the next few weeks I heard quite a bit about his military life.Rod had also collected several thousand DVDs, and unsurprising, most of them were war-themed. Concerned I might get bored after work, he pressed upon me a spare DVD player, RCA leads and the first of many tall stacks of war movies and documentaries for me to watch. Man, I never knew there were so many battles. I watched The Battle of This and Battle of That and soon it all beganto blur into a series of explosions, stubbled jaws clamped on cigars and crackly radio commands. Some battles went to three discs!As I returned these slices of combat heaven, Rod would seriously quiz me on each theater of war, battle and skirmish I’d watched. Scarcely acknowledging my uneducated, shell-shocked replies, he’d launch into exhaustive dissertations of the tactics, fighting men and weapons portrayed in each film. He also had many theories and ideas about current affairs and potential flash-points. Harping on about its proximity and imperial ambitions, Rod worried about Indonesia the most.One day, barely keeping up with all things military – past, present and future – I asked him whathe thought the plan for the coal port here was. “What plan?” Rod looked puzzled. “Y’know . . . when they invade.”His eyebrows shot up in shock. “This is one of the very first places they’ll come to,” I continued. “I reckon at least two paratroop battalions with armored fighting vehicles, maybe a tank or two. Para-drops of mortars, recoilless rifles and RPGs, plus marines in littoral fast-boats assaulting the beach. Helicopter gunships and ground-attack planes providing air support of course.”Rod reeled and spluttered. “Here?” “Yeah. Wouldn’t you? Major coal port and all.”The absolute strategic rightness of it nearly floored him. Red-faced, he looked around as though the door was about to be blown in.I couldn’t help myself. “You better brush up on your nasi goreng Chef. And get the bar to order in Bintang. Lots of Bintang.”

Published on October 17, 2019 16:54

September 22, 2019

Black Money

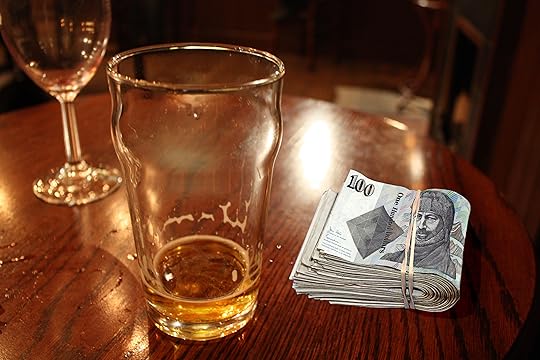

When I started out, the restaurant industry drank from a stream of black money. Hospitality was, as the Japanese call it, a water trade where money flowed in and out. This state of affairs was normal, natural - quite casual in fact, and benefited customers, workers, suppliers and owners alike. It wasn't much chop for tax office coffers, but this sub rosa system under-wrote a hell of a lot of good times.In that pre-EFTPOS era, cash was king. At day's end the till contained a few cheques (would you trust them today?) and some carbon copy imprints from the high rollers with credit cards, but cash would be the absolute majority of the takings. Crucially, all that moolah came straight from the customer's hand, digitally unrecorded, innocent and free.With this daily deluge, large denomination notes often dripped through the cracks. When the owner, or a spouse or family member, is the cashier, then it ain't real hard to render down a cash stuffed till into two streams of income – one legit, the other pure cheeky profit. Good operators could skim 20% or more of the days takings, and canny owners with an eye for selling their business down the track would have two sets of books - and maybe an artful accountant in on the joke as well. Totally AWOL from the expenses column, cash flowed out too - as discounted wages and produce purchases. Whole-sale suppliers would offer price mark-downs on cash payments, the understanding being that any invoice was just a list of what had been ordered - not a record of payment due. Seasonal suppliers at kitchen back doors carried cases of good stuff and required no signatures on receipts - just dollar bills thanks.In the kitchen, chefs, cooks - even dish pigs - worked a forty five hour week on the books, paid their twenty something percent tax and were generally model citizens. Then they did another twenty or thirty hours for cash in hand - at a slightly lower rate of pay that rewarded both them and the owner. It was a two way street that everyone was most happy to meet on.A whole stripe of customer didn't miss out on a place at the table either, as tax laws back then provided a special incentive for those in business to stuff their faces and get royally pissed. While taking ' meetings' over a three course lunch and half a dozen bottles of wine they could claim it all as a business expense, and they did. Sometimes daily.Talk about trickle down economics! Owners, buoyant on a sea of filthy lucre would spread their largess around. Good customers got free desserts, bonus entrees, comped coffees and bottles of wine gratis. Really fun regulars got invited to settle in after close as the top shelf liquor flowed. Staff would routinely get a knock off drink, or three if the owner liked to party with them, and they'd end up spending some of their black money at the bar. The business types would kick on too, cheerfully arguing with equally sloshed owners about who was paying for the next round. I saw this scenario many times over the rim of my glass.With all that 'extra' money the roaring eighties were full of delirious abundance, often descending into excess. Folks would eat two dozen oysters as an entree and share six desserts on a table of four. I could easily eat a 600 gram steak and drink ten beers in a sitting. Easily. I'm putting on weight just thinking about it. But the tax office, ever keen to keep us lean, has always reserved a special kind of suspicion for deductions that involve anything pleasurable. They wheeled out the Fringe Benefits Tax and blew away claiming food and drinks as a business expense. Now only the rich bastards could afford to have six hour lunches.Actually, some of those retro rorts never really stopped - they just got high tech. Outlaw owners today can hit the till with a zapper – sales suppression software. Kept on a USB stick and used remotely, these programs are smart. They'll delete sales records, re-number and re-calculate records of each receipt. Then they'll produce perfectly conforming financial reports for the taxation office to happily sign off on. Zappers can also escape the confines of the cash register and slip into stock inventory and employee time records, and make the facts fit the fiction. A $10,000 day with a full complement of staff and major depletions of the cold rooms and bar fridges can be shrunk to a pretty decent $7,000 day.Eating out is about gratification, often spur of the moment, and it's a straight-off-the-street thrill not unlike purchasing sex or drugs. With millions of B2C (business to consumer) transactions each day, all involving pretty small amounts of money, it will always be hard for the government to police their skim. The tax office estimates that 45% of businesses in the restaurant, cafe, takeaway and catering industry are cash only, so it's a sure bet that black money is going to be around for a long time to come – probably forever.I don't recall the world falling apart back when things were looser. I'm no tax protester but what's wrong with a little illicit liquidity lubricating the lives of some damn hard workers - the kitchen crew sweating over stoves, the owners freaking out over shrinking profits and the suppliers facing rising food and energy costs. Anyone of them would love to have tax-free allowances of two or three hundred dollars a day - you know like politicians get. And any government worried about the 'deficit' this naughty black money creates could just make a couple of multinational corporations pay their taxes. There'd be lots of knock-off drinks for everyone then, let alone mortgage repayments, school fees and medical expenses.

When I started out, the restaurant industry drank from a stream of black money. Hospitality was, as the Japanese call it, a water trade where money flowed in and out. This state of affairs was normal, natural - quite casual in fact, and benefited customers, workers, suppliers and owners alike. It wasn't much chop for tax office coffers, but this sub rosa system under-wrote a hell of a lot of good times.In that pre-EFTPOS era, cash was king. At day's end the till contained a few cheques (would you trust them today?) and some carbon copy imprints from the high rollers with credit cards, but cash would be the absolute majority of the takings. Crucially, all that moolah came straight from the customer's hand, digitally unrecorded, innocent and free.With this daily deluge, large denomination notes often dripped through the cracks. When the owner, or a spouse or family member, is the cashier, then it ain't real hard to render down a cash stuffed till into two streams of income – one legit, the other pure cheeky profit. Good operators could skim 20% or more of the days takings, and canny owners with an eye for selling their business down the track would have two sets of books - and maybe an artful accountant in on the joke as well. Totally AWOL from the expenses column, cash flowed out too - as discounted wages and produce purchases. Whole-sale suppliers would offer price mark-downs on cash payments, the understanding being that any invoice was just a list of what had been ordered - not a record of payment due. Seasonal suppliers at kitchen back doors carried cases of good stuff and required no signatures on receipts - just dollar bills thanks.In the kitchen, chefs, cooks - even dish pigs - worked a forty five hour week on the books, paid their twenty something percent tax and were generally model citizens. Then they did another twenty or thirty hours for cash in hand - at a slightly lower rate of pay that rewarded both them and the owner. It was a two way street that everyone was most happy to meet on.A whole stripe of customer didn't miss out on a place at the table either, as tax laws back then provided a special incentive for those in business to stuff their faces and get royally pissed. While taking ' meetings' over a three course lunch and half a dozen bottles of wine they could claim it all as a business expense, and they did. Sometimes daily.Talk about trickle down economics! Owners, buoyant on a sea of filthy lucre would spread their largess around. Good customers got free desserts, bonus entrees, comped coffees and bottles of wine gratis. Really fun regulars got invited to settle in after close as the top shelf liquor flowed. Staff would routinely get a knock off drink, or three if the owner liked to party with them, and they'd end up spending some of their black money at the bar. The business types would kick on too, cheerfully arguing with equally sloshed owners about who was paying for the next round. I saw this scenario many times over the rim of my glass.With all that 'extra' money the roaring eighties were full of delirious abundance, often descending into excess. Folks would eat two dozen oysters as an entree and share six desserts on a table of four. I could easily eat a 600 gram steak and drink ten beers in a sitting. Easily. I'm putting on weight just thinking about it. But the tax office, ever keen to keep us lean, has always reserved a special kind of suspicion for deductions that involve anything pleasurable. They wheeled out the Fringe Benefits Tax and blew away claiming food and drinks as a business expense. Now only the rich bastards could afford to have six hour lunches.Actually, some of those retro rorts never really stopped - they just got high tech. Outlaw owners today can hit the till with a zapper – sales suppression software. Kept on a USB stick and used remotely, these programs are smart. They'll delete sales records, re-number and re-calculate records of each receipt. Then they'll produce perfectly conforming financial reports for the taxation office to happily sign off on. Zappers can also escape the confines of the cash register and slip into stock inventory and employee time records, and make the facts fit the fiction. A $10,000 day with a full complement of staff and major depletions of the cold rooms and bar fridges can be shrunk to a pretty decent $7,000 day.Eating out is about gratification, often spur of the moment, and it's a straight-off-the-street thrill not unlike purchasing sex or drugs. With millions of B2C (business to consumer) transactions each day, all involving pretty small amounts of money, it will always be hard for the government to police their skim. The tax office estimates that 45% of businesses in the restaurant, cafe, takeaway and catering industry are cash only, so it's a sure bet that black money is going to be around for a long time to come – probably forever.I don't recall the world falling apart back when things were looser. I'm no tax protester but what's wrong with a little illicit liquidity lubricating the lives of some damn hard workers - the kitchen crew sweating over stoves, the owners freaking out over shrinking profits and the suppliers facing rising food and energy costs. Anyone of them would love to have tax-free allowances of two or three hundred dollars a day - you know like politicians get. And any government worried about the 'deficit' this naughty black money creates could just make a couple of multinational corporations pay their taxes. There'd be lots of knock-off drinks for everyone then, let alone mortgage repayments, school fees and medical expenses.

Published on September 22, 2019 00:13

September 9, 2019

Bucket of Blood