Liza Libes's Blog, page 2

July 26, 2024

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land - Background and Intro

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is perhaps one of my favorite poems of all time. Certainly, it’s the most abstruse poem out of my array of favorites—it’s also the poem I analyzed extensively for my MA thesis several years ago.

The Waste Land is widely considered to be one of the 20th century’s greatest and most profound poems, and rightly so. Over the next several months, we’ll be tackling The Waste Land through a five-part series of articles and videos.

You can check out my video intro to the Waste Land here and read the full poem here .

I first came across the Waste Land in the 7th grade when I was just 12 years old. That afternoon, my 7th grade English teacher introduced our class to Wallace Stevens’ poem “The Snow Man” through the unorthodox method of having us all stand around outside for an hour on the frigid January morning so that we could become, in his words, literal snowmen. As we rushed back into the classroom to revel in the power of modern heat technology, my teacher began to lecture us about the poem’s bleak yet hopeful underpinnings and likened its conclusion to Eliot’s The Waste Land—both poems find recourse in the meditative aspect of Eastern philosophy. Needless to say, my curiosity was piqued, especially after my teacher left us with the thought that The Waste Land is probably one of the world’s most difficult poems to comprehend. Twelve-year-old Liza was up for the challenge.

Of course, at twelve, slogging through the poem and missing 90% of its literary, philosophical and musical references, I came away from the poem more baffled than satisfied yet resolved to revisit the work as I grew older.

By the age of eighteen, picking up the poem once again, I was absolutely hooked.

The Waste Land is a poem about the futility of human desire. Published in 1922, the poem originally ran a whopping 19 pages long and would have likely retained its epic length had it not been edited by Eliot’s friend and fellow modernist poet Ezra Pound. Eliot later dedicated the poem to Pound, whom he called il miglior fabbro—“the better craftsman.”

The Waste Land is divided into five sections, each of which mirrors an act of a Shakespearean drama. Eliot was a staunch proponent of tradition, arguing, in his famous essay Tradition and the Individual Talent, that one must first understand the history of the literary tradition before leaving a mark upon it. Eliot’s homage to Shakespeare is a nod towards literary dialogue and a key component to understanding the development of his poem.

Throughout much of his work, Eliot aims to spark conversation with the figures of the literary past. In the notes to The Waste Land, for instance, he cites a book called from Ritual to Romance by Jessie L. Weston as his primary inspiration. “Not only the title,” writes Eliot, “but the plan and a good deal of the incidental symbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jessie L. Weston’s book on the Grail legend.” We might presume that Eliot’s fascination for antiquity led him to select Arthurian romance as the backdrop for his poem.

As its title suggests, The Waste Land tackles the issue of societal decay through a reinterpretation of Arthurian legend. Just as James Joyce’s Ulysses is a loose retelling of Odysseus' homecoming in Homer’s epic The Odyssey, Eliot’s The Waste Land broadly follows the story of the Fisher King from the famous Perceval myth. In Perceval (the same myth that gives us the legend of the Holy Grail), we learn that the Fisher King once presided over a thriving kingdom, yet a wound on his leg has rendered him barren, leaving his kingdom to fester and decay. Though Arthurian myths—in the vein of the Greek epic tradition—may have been disseminated orally, artists throughout literary history have attempted to capture the story of the Fisher King in verse and prose alike: Chrétien de Troyes in his verse romance Perceval, Wolfram von Eschenbach in his chivalric romance Parzival, and Thomas Malory in his Arthurian behemoth Le Morte d'Arthur, to name a few. Yet Eliot’s Fisher King is perhaps best known as King Amfortas from Richard Wagner’s opera Parsifal, and indeed, it is no accident that Eliot, a great admirer of Wagner, quotes from several of his operas throughout the poem, borrowing motifs from the composer to bring his story to life.

Understanding The Waste Land’s Wagnerian parallel is crucial to tapping into the poem’s deeper meaning: Wagner’s persistent commentary on the unnatural and even sickly nature of many human relationships strikes an important chord with the overall message of The Waste Land, and characters from Wagner’s operas and Eliot’s Waste Land alike evince a vehement urge to attain genuine connections in the face of desolation and despair. Eliot thus uses the Wagnerian trope of unattainable and unnatural desire to stress the perils to which modern society has subjected itself. But though Fisher King might stand for infertility, in Eliot’s retelling of the myth, he becomes a vehicle for bringing life back from the dead and imbuing meaning into an absurd and senseless world. Just like the Perceval myth, The Waste Land becomes a quest story—a story of recovery, fertility, and coherence.

In looking to Wagner, Eliot offers a potential solution to societal decay through the revitalization and transformation of human relationships—a topic we’ll further explore in our next analysis of The Waste Land.

Stay tuned for my next installment of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land analysis, where we’ll dive further into The Waste Land’s Wagnerian parallel, discussing human relationships in the first section of the poem—“The Burial of the Dead.”

July 19, 2024

Top 10 Books of All Time

What are my top 10 books of all time and why? It’s a difficult question, albeit one I get asked quite often. To please both my interrogators and my indecisive, literary soul, I’ve made a compromise and added an eleventh book to my list (I really couldn't choose just 10).

Here are my top 10 (+1 bonus) books and my fast take on why each of these books matters and what makes them amazing.

10. Middlemarch by George Eliot

As Wikipedia puts it, this is a novel about “The Woman Question.” Middlemarch follows the story of the 19-year-old provincial orphan Dorothea Brooke and her marriage to the scholarly yet still Edward Causabon. Meanwhile, over in the town, we meet the doctor Tertius Lydgate and follow his own adventures, eventually seeing an overlap between the two as Lydgate comes to tend to Casaubon during his decline. It’s a novel about gender norms and marriage and love, yet a unique take on these themes in that the plot does not center around a need or desire to marry as we might see in a Jane Austen Novel.

9. White Noise by Don DeLillo

Flashing forward a hundred years into the future, we get Don DeLillo’s White Noise, which famously addresses the “fear of death” question that is so central to the human experience in the most bizarre way possible. Our protagonist is a “Hitler Studies” professor, a playful jab at American academic institutions. White Noise is a novel about a typical American family who struggles to understand the absurdity of life. The novel’s fragmented structure reflects the fragmented nature of postmodern thought, and its critique of consumerism and media examines the effects of the postmodern era. Themes of existential dread and paranoia also pervade the work, emphasizing the fear of both life and death that characterize the postmodern psyche. It was my personal introduction to postmodernism and made me quite the big DeLillo fan.

8: Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

We have all met a Count Vronsky in our lives. Anna Karenina is Tolstoy’s masterful work of literature on domestic life. At the center of the novel of course lies their affair, but through the character Levin and his eventual marriage to Kitty, we also tackle themes of Christianity and death—two philosophical topics that are hallmarks of Tolstoy’s work.

7: The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

If Middlemarch is about “The Woman Question,” The Bell Jar is about “The Sex Question.” The novel is fraught and autobiographical—much of Plath’s own experience with depression is chronicled in this book through the eyes of Esther Greenwood, a naive college sophomore who finds herself in New York City for an internship. Esther is neither content with nor interested in the work she’s doing at her fashion magazine—her attention wanders, instead, to sex and love as she reminisces on the nature of relationships and death. The Bell Jar is my favorite book written by a woman about what it is like to be a woman in the face of society and men. It also tackles questions of mental health that are still with us today. It’s worth a read!

6: Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Today, Brideshead Revisited is best known for being an early novel about homosexuality, but the novel is perhaps more principally about Catholicism and the decay of the British nobility. The implied homosexual dynamic between Charles and Sebastian figures in more broadly and relevantly when we consider the Catholic layer, presenting an explanation of why Waugh never allows the relationship to play out or why he breaks it off so early in the novel. Oh, and don’t forget my favorite character—Sebastian’ teddy bear Aloysius.

5: The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

This is one of the few books by a man that is very self-aware about men. The Unbearable Lightness of Being follows two couples and their disparate relationships. We meet Tomas and Tereza, who are in a polyamorous relationship at Tomas’s instigation. The novel explores human sexual impulses and desires and is set against the backdrop of the 1968 Prague Spring.

4. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov is such a master of his craft (English was his third language!) that he manages to create beauty with respect to one of the most vile topics known to man. Because of its subject matter, this book gets quite a bad rep from people who haven’t read it, but I don’t know a single person who has read Lolita who still turns their nose up in disgust. It’s a masterful work in literary history and inaugurates Nabokov amongst the ranks of masterful psychologists (and writers, of course).

3. The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

The Sun Also Rises is a novel about a youthful generation charged with class, glamor, and sophistication. This is the Lost Generation, the disillusioned expatriates who search for meaning in post-WWI Europe—for a way to live rather than to simply exist. Yet their grandiosity acts as nothing more than a veneer for their sickness—sickness not as an illness or even as a plea for survivalism but as incapacitation and artificiality. The Lost Generation, through its inauguration of a new dimension of hope, also ushers in a new era of repression, an existence that is living without feeling and expression of feeling. Hemingway’s writing itself acts as a metaphor for this repression: he uses narratorial omission to say what he does not actually mean to say, and while this is a brilliant technique for a novel age of art, it leaves many of his characters pathetic and despondent, living but not living at all, unable to push past the façade of grandeur to express their true desires, unable to live a truly meaningful life. An Lady Brett Ashley is the coolest f*cking character ever invented.

2. The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Master and Margarita is a critique of the Soviet Union through a devil who roams the streets of Moscow and a cat named Behemoth (which is actually funnier in Russian because behemoth is also the word for “hippo”). Coming from a Post-Soviet household, I resonate deeply with the novel’s commentary on decaying social norms in the Soviet Union, as well as its satire on Soviet life. The principal theme in the novel is the erosion of traditional Christian morals through the eradication of religion under the Soviet regime; it certainly leaves us with something to think about today as well.

1. The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

This is the deepest novel about the nature of religion and man ever written. I seem to like theological dramas. That must be because religion provides us with a moral framework to ask and answer some of the most important questions known to man. The Brothers K tells the story of three brothers—Alyosha, Dmitri and Ivan—and the investigation of the murder of their father, Fyodor Karamazov. The most profound meditation on the nature of religion occurs halfway through the book in Ivan’s story of The Grand Inquisitor, a tale of religion and free will.

0. The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

My all-time favorite book is William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, which tells the story of the downfall of the Compson family through four different perspectives.My favorite section is by far the second one, which is narrated by the neurotic nineteen-year-old Quentin Compson and establishes Faulkner as a master of human psychology. Quentin, caught up in the ideals of the old South, obsessed with his little sister Caddy, and unable to adjust to his time at Harvard, meets a gloomy demise, but he also appears in one of Faulkner's other monumental works—Absalom, Absalom! The book’s title comes from Macbeth’s famous “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” monologue and reflects the book’s focus on the absurdity of life.

WOW was it difficult to condense those great books into pithy paragraphs. I hope that piqued your interest. Happy reading!

July 13, 2024

How to Develop a Personal Brand and Online Presence

In 2015, I realized that I couldn't call myself a writer without some semblance of an online presence. I had been dreading going public with my work for the entirety of high school: my poems and novels were so deeply personal that I shied away from sharing them with even the closest people in my life. At a certain point, however, I had to come to terms with the world that we live in and realize that if I ever wanted to make any sort of a name for myself, I would need to succumb to fostering an online presence—a personal brand.

Over the years, the little blog I created at the start of college evolved into Pens and Poison, my writing project and brand that has gained over 30k followers across various platforms and social media outlets. Establishing a personal brand has helped me push out my work to audiences across the globe, and with every passing day, my posts and poems reach an increasing number of people.

While personal branding might be most important for a writer or any other sort of intellectual looking to share their pursuits with a broader audience, establishing an online presence will help both students and professionals in any field secure basic recognition and establish legitimacy for their work.

So how do we start?

1. Brainstorm a Brand Name

To begin, we’ll start with the basics: your brand name. You can use your full name as your brand name, or you can brainstorm a brand name that accords with the particular subject or audience you’ll be reaching. (For instance, my brand name, Pens and Poison, speaks to literature lovers.) In the era of AI, there are luckily a few tools that can help you brainstorm names if you’re stuck. I like the website , which can help you generate both a name for your project and an image for yourself.

2. Create a Logo and Brand Kit

In the age of media, it’s important to establish a cohesive brand identity—which includes colors and aesthetics! You’ll want to first think of what you want your brand to elicit—what color palette and fonts might best appeal to your audiences. Let’s take a look at my personal brand—Pens and Poison—as an example.

My brand logo contains a few noticeable elements: an ink pen nib, cursive font, and an array of purples. Of course, the pen nib is a stand-in for writerly pursuits, the cursive gives the logo an aura of nostalgic creativity, and the purples give off a sense of whimsy. Immediately when glancing at my brand, you get a glimpse into what’s to come.

You can create a logo over on Canva and choose several colors to get started.

3. Create a Personal Website

Now you’re ready to create your personal website! Go ahead and download your logo from Canva (preferably with the background removed) and hop over to your desired website host. Here are a couple that you can choose from:

The website hosts all accomplish much of the same purpose, but depending on what you’re going for, you might see some variation among these sites. Squarespace sites, for instance, tend to be the most “visually striking” but come with the least amount of customization tools. I use Squarespace for my personal website for ease of use and Odoo for my company’s website, which gives us the greatest number of customizable features.

Once you choose your website, you can decide which pages you’ll want to feature in the “navigation” bar of your website. These will be the primary pages that users can use to learn more about your brand. On my personal website, I have the following:

POETRY: A page with my selected poetic works

BLOG: Features my weekly blog posts and other thoughts!

PUBLICATIONS: A list of selected publications my work has been published in

VENTURES: Links to my company, Invictus Prep, and the Pens and Poison YouTube project

NEWS: Big updates about my work

SHOP: A link to my merch shop

ABOUT: More information about me

These are appropriate pages for a writer. If you’re a mathematical researcher, you might want a tab highlighting your research and another with a full CV. You might also consider a publications tab. Finally, you’ll want to have an “About” page with a bio that summarizes your work.

4. Establish a Blog on Your Personal Website

I am biased, of course, because I am a writer, but I do think that establishing a personal blog is a great way to get your name out there and to start building your follower base. My blog is devoted to all things literature and writing and other miscellaneous posts such as this one, but if you are tech guy, you can create a blog devoted to the development of Artificial Intelligence, for instance. The world is your oyster on this one, but the idea is to post consistently to engage your audience and create a following for yourself.

5. Create Social Media Channels for Your Brand

Now that you’re online, you’ll want to spread the word! The best way to do so is by creating social media channels for yourself. Here are the basics to get you started:

Twitter (X)

You don’t even need all of these (I don’t have TikTok, for instance), but a couple to start out with will help you get the word out there about yourself!

6. Create Profiles on Other Industry-specific Websites

Another great way to get your name out there is to share your work on other platforms that are relevant to your industry. As a writer, I have accounts set up on Substack and Medium, for instance, but if you’re a software developer, you might consider creating a profile on Github, and if you’re an entrepreneur, you might want to feature yourself and your company on Crunchbase or Wellfound. These websites will help you get your name out there and appear faster in Google Search.

7. Start Sharing!

Now that you’re an online wizard, get to spreading the word through engaging posts and content. You’ve taken the first step to establishing your personal brand and should hopefully gain some recognition soon!

And don’t forget to follow your favorite writer Liza Libes over on Pens and Poison.

July 6, 2024

W. H. Auden's "Musée des Beaux Arts"

What is an ekphrastic poem? One famous example is the “Musée des Beaux Arts,” a poem by the British modernist poet W.H. Auden that was inspired by his visit to the fine arts museum in Brussels.

You can access the poem here to follow along. You can also watch my analysis over on YouTube here .

Auden wrote “Musée des Beaux Arts” in 1938 on the cusp of World War II in a world of political unrest. You might imagine that the suffering of the war might have presented an apt backdrop to this poem, which covers the topic of human suffering, but the poem is too leisurely and light to be in reference to a war—it’s set in a museum, after all.

Auden was inspired by a particular painting hanging in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Belgium. It’s a painting by Breughel, one of the most significant Dutch painters of the Dutch Golden Age known for his landscapes scenes.

The poem in question here is Breughel’s Icarus, whose composition is in keeping with what we might expect of Breughel’s dedication to the pastoral landscape. The painting appears in the second stanza of the poem and references one Icarus, the Greek mythological son of Daedalus. If you remember your Greek mythology, or if you’ve studied James Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, whose main character is named after the mythological Daedalus, you’ll remember Daedalus as the creator of the labyrinth that held the half-bull half-human Minotaur. Later on, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Daedalus reappears with his son Icarus and is tasked with creating wings. Because the wings are made of bird’s feathers and beeswax, Daedalus warns Icarus not to fly too close to the sun. Icarus, of course, as any brash Greek hero, disobeys his father’s admonition and flies towards the sun. As we are left to contemplate his hubris, Icarus plummets to the ground, his wings melting under the sun’s heat, and drowns in the sea.

You might thus expect a flamboyant painting that depicts the heroic Icarus ascending towards the sun, perhaps replete with bright reds and yellows, but that’s not the painting we get at all. Instead, we have a verdant landscape with a plowman, feathery green trees, a shepherd with his dog, and ships off in the distance. In a modest corner, we see Icarus’ limbs poke out from the water. And no one seems to notice his descent.

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Bruegel the Elder | Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Museum of Fine Arts

Auden’s poem alludes directly to Breughel’s painting through a literary device called ekphrasis, which allows a poet, through vivid imagery, to put art to words and create a vibrant scene. One of the earliest and maybe most famous examples of ekphrasis can be found in Book 18 of Homer’s epic The Iliad in a description of Achilles’ shield. Auden wrote several ekphrastic poems, and in fact, his other famous ekphrastic poem is his take on Achilles’ shield through the poem “The Shield of Achilles.”

Yet in “Musée des Beaux Arts,” we don’t arrive at the ekphrasis until the latter half of the piece. Instead, we open with the lines “About suffering they were never wrong,” a sentiment that promptly reveals the poem’s subject matter: humanity’s indifference to suffering and its corresponding focus on quotidian life. The poem’s tone mirrors the feeling of Breughel’s painting: its diction creates a quasi-pastoral scene with shepherds and ordinary people going about their day rather than heroic figures falling to their death.

Auden’s poem concerns ordinary human experience, as well as how suffering is a part of everyday life, yet Auden doesn’t negatively judge the rote pace of human life or the more ignorant people who are unaware of the profound suffering around them. He seems to be suggesting that suffering is a typical part of the human experience.

You might notice that our opening line is a bit odd—it’s written in a sort of Yoda speak, with the predicate at the start of the sentence and the subject at the end: “About suffering they were never wrong, the old masters.” Auden liked to break literary conventions: he has many of these convoluted sentences throughout his work; he also loves adverbs: “walking dully along” or “reverently, passionately waiting.” I teach writing to teenagers, and the two rules of writing I always push—write sentences in the simplest, most straightforward way and use adverbs sparingly—are the very rules that Auden chooses to break, reflecting his belief that human beings don’t have to be relegated to a fixed standard. The effect in the poem is something playful or even ordinary—prose that is, perhaps, more innocent.

Certainly, the poem concerns innocence. We witness children who are actively “skating,” ignorant of the more serious and devoted elderly people who are “waiting” for Jesus’ birth. If you note the rhymes, which come at irregular intervals and are somewhat cloaked within the text, you’ll see that the rhymes link ideas together. For instance, “waiting” and “skating” present a contrast between the experience of suffering and the ordinary world. The children don’t care about suffering, for how could they be privy to its existence? And what of the dogs? They go about their life—their “doggy life” (a fun one). The poem is full of enjambment as well—the literary device where one line spils over to the next. Here, the enjambment creates a sense of perpetual motion and reemphasizes Auden’s idea that life goes on—despite all the suffering that comes with it.

In the second stanza, we encounter Breughel’s painting and Auden’s love of ekphrasis. Auden notes how the poem's actors turn leisurely (there’s your adverb again) away from the disaster of Icarus’ fall. The plowman goes about his life; the ships sail calmly on past Icarus drowning in the water.

Does Auden excuse us for ignoring suffering in the world? That is certainly my reading of the poem—Auden seems to be arguing that while it might not be justified to turn a blind eye to suffering, it is certainly natural to go about life in ignorance of it. Auden thus captures a central facet of the human experience: it is ordinary, quotidian—a life without recourse to perils. And maybe, he suggests, that’s all right.

July 1, 2024

Weekly Literary Spotlight: László Krasznahorkai

Laszlo Krasznahorkai, born on January 5th, 1954, in Gyula, Hungary, is a contemporary Hungarian novelist and screenwriter known for his complex, meandering prose and his fascination with apocalyptic themes. In this week’s Literary Spotlight, we briefly examine his life and glimpse his hypnotic, one-of-a-kind literary world.

Krasznahorkai László (Gyula, 1954. január 5. –) Kossuth-díjas magyar író, 2004 óta a Digitális Irodalmi Akadémia és a Széchenyi Irodalmi és Művészeti Akadémia tagja.

Life Overview:

Krasznahorkai's upbringing in communist Hungary deeply influenced his worldview and literary style. He studied law and Hungarian literature at the University of Szeged and later at the Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, though he never pursued a conventional legal career. Instead, he immersed himself in creating works of literature, beginning with short stories and eventually gravitating toward novels.

Krasznahorkai's literary breakthrough came with his first novel, Satantango, published in 1985. The novel's critical success established him as a formidable voice in Hungarian literature. Throughout his career, he has been a frequent collaborator with filmmakers, most notably with Hungarian director Béla Tarr. Their collaborations, including the adaptation of Satantango into a seven-hour film, have been critically acclaimed and have cemented Krasznahorkai's reputation as a key figure in contemporary literature and cinema.

Stylistic Overview:

Krasznahorkai's writing is characterized by long, winding sentences and a unique narrative style that often eschews traditional punctuation and structure. His prose can be challenging, requiring readers to engage deeply with the text. This complexity is a deliberate choice, reflecting the chaotic and often overwhelming nature of the worlds he creates. Krasznahorkai's narratives are imbued with a sense of doom and apocalypse, exploring themes of decay, existential despair, and the fragility of the collective human condition.

One of his signature stylistic elements is his use of extended monologues and internal dialogues. These devices allow readers to delve into his characters' psyches and uncover their innermost fears, desires, and existential musings. His narrative voice is often described as hypnotic, drawing readers into trance-like states that mirror the disintegration and madness often illustrated in his stories.

Another notable aspect of Krasznahorkai's style is his ability to blend the mundane with the metaphysical. His works frequently explore the intersection of everyday life and deep philosophical questions, creating a surreal atmosphere that challenges readers' perceptions of reality. This fusion of the ordinary and the extraordinary is a hallmark of his literary genius.

Notable Works:

Satantango (1985):

Arguably Krasznahorkai's most famous work, Satantango follows the lives of residents of a decaying Hungarian village as they grapple with despair and hope for salvation through the return of a charismatic but dubious figure, Irimiás. The intricate structure and dark, atmospheric narrative of this extraordinary novel have made it a landmark in postmodern literature.

The Melancholy of Resistance (1989):

This novel presents a dystopian vision of a small town on the brink of collapse. The story centers around the arrival of a mysterious circus and the chaotic events that ensue. Through its complex characters and haunting prose, The Melancholy of Resistance explores themes of power, control, and the human propensity for self-destruction. Like Satantango, it was later adapted into the film Werckmeister Harmonies, also directed by Béla Tarr.

Seiobo There Below (2008):

In this relatively recent work, Krasznahorkai shifts his gaze to the intersection of art and spirituality. The novel is a collection of interconnected stories that span various cultures and historical periods, all linked by the presence of the Japanese goddess Seiobo. Through these narratives, Krasznahorkai examines the nature of beauty, the sublime, and the transcendent power of art.

Krasznahorkai's contributions to contemporary literature are challenging yet profound. His meditations on existential themes and his ability to blend the everyday with the metaphysical ensure that his works will continue to be studied and appreciated for years to come.

Darkness at Noon: A Liza's Book Club Study Guide

Click here to access a downloadable PDF

OverviewDarkness at Noon is a book about the political dissident Nikolai Salmanovich Rubashov, a high-ranking member of the Party who finds himself imprisoned and accused of treason. We’re never told what party he’s a member of, or even what country the book is set in, but given the author’s own life and the parallels to the Stalinist purges of the 1930s, we can assume that the book is, if not set in, then at least heavily influenced by the Soviet Union and its intense political repression. One of the big giveaways of the Soviet influence is the character of “Number One,” the leader of the Party, whose portrait hangs in virtually every room in the novel. Number One is, of course, a parallel to Joseph Stalin, in much the same way that the pig Napoleon is a stand-in for Stalin in George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

Arthur Koestler: Short Biography

Arthur Koestler: Short BiographyArthur Koestler was born in 1905 in Budapest, Hungary. He studied science and engineering before becoming a journalist; his journalistic career took him across Europe and sparked his interest and involvement in politics.

In the 1930s, Koestler joined the Communist Party, driven by a strong belief in its ideals and the promise of a better, more just society. But his experiences in the Soviet Union and the Spanish Civil War led him to see the stark contrast between the Party's ideology and its actions. In fact, the writer George Orwell, who wrote a similar critique of the Soviet regime, also fought in the Spanish Civil War, on the side of the “Reds,” or Republicans (the Stalinist-backed left-wing side), the same side that Koestler fought on. Both writers emerged from that war with deep criticisms of communism and the internal struggles they witnessed in the Communist party.

Koestler witnessed the brutal realities of totalitarian regimes, and this began to erode his faith in communism. His experience of incarceration and political persecution likely directly influenced the creation of Darkness at Noon and the experiences of his character Rubashov, whose journey partly mirrors Koestler's own. The novel critiques totalitarianism and is a reflection of Koestler's belief in the importance of individual conscience over blind obedience to the state.

Understanding Koestler's personal history and ideological evolution can help us appreciate Darkness at Noon not just as a political novel, but as a deeply personal and philosophical exploration of morality and human resilience.

CharactersNikola Salmonovich Rubashov

Our protagonist, Rubashov is a high-ranking member of the Party in an unnamed totalitarian state. Rubashov is a dedicated revolutionary and a former hero of the revolution, but he is arrested and imprisoned by the very regime he helped to erect.

Number One

The anonymous leader of the party likely modeled after the USSR’s Joseph Stalin. His portrait hangs in virtually every room in the novel.

Ivanov

Rubashov’s first interrogator and old friend. A high-ranking official within the Party, Ivanov is both an intellectual and pragmatic character. He attempts to justify the party’s harsh methods to Rubashov by invoking the net positive that these methods bring to the people and the state. Despite their past friendship, Ivanov and Rubashov approach each other somewhat coldly, as Ivanov’s main goal is to extract a confession from Rubshov.

Gletkin

Gletkin is a younger, more zealous Party official who takes over Rubashov's interrogation in the third section of the novel. Unlike Ivanov, who represents the old guard of the revolution, Gletkin embodies the new, more ruthless generation of Party members who have never experienced life before the revolution. Gletkin comes from a lower-class background and is determined to obtain Rubashov's confession through brutal interrogation techniques.

Orlova

Orlova is Rubashov's former secretary and lover. She is a loyal Party member whom Rubashov ultimately sacrifices in order to save his own fate.

No. 402

A fellow prisoner who communicates with Rubashov through the cell wall. No. 402 is a former aristocrat who is skeptical of Rubashov.

StructureThe novel is divided into three parts—three separate interrogations that Rubashov undergoes. The first part of the novel sets the stage for Rubashov’s arrest and initial imprisonment—in fact, the “interrogation” itself doesn’t occur until the very end of the section.

Part 1

During part 1, Rubashov is interrogated by his old comrade Ivanov.

Ivanov represents the old guard of the Party and shares a long history with Rubashov. As I was reading, I was actually surprised at some of the dialogue—to me, it felt more like philosophical discourse than an interrogation. Philosophical discourse and also psychological manipulation: in this section, Ivanov tries to persuade Rubashov to confess to the charges against him by arguing that doing so will not only be for the greater good of the Party but will also help him get off with a more mild sentence. Their encounter is marked by both nostalgia and a clash of ideals, as both men reflect on the revolution they once believed in.

Part 2

During the second part of the book, we reach the second “interrogation,” again between Ivanov and Rubashov. In this section, we meet Gletkin, who confers with Ivanov and has a slightly different philosophy with respect to Rubashov’s interrogation. Gletkin believes in a more cold-hearted approach to the interrogation and urges Ivanov to resort to physical torture. Ivanov refuses and instead visits Rubashov in his cell to carry on their previous conversation. In part two, we learn about the death of Bogrov, another political prisoner, who was sentenced for a disagreement regarding optimal submarine size. Bogrov is an old roommate of Rubashov’s; he is dragged in front of Rubashov’s cell before his execution, and his last word is “Rubashov.” This image begins to haunt Rubashov, and he reflects on the innocent lives that he has sacrificed for the sake of the Party, concentrating particularly on an old lover of his named Orlova, whose death he allowed in order to save his own guts. Orlova takes on a new vividness in his mind, and her death is humanized. Horrified, Rubashov begins to develop a clear conscience and value system that was absent from his earlier character. As Ivanov comes into Rubashov’s cell, he begins to mock Rubashov for these Christian values and argues that this sort of morality—what he calls “anti-vivisectional morality”—is no good for the progression of history. In his optimal vivisectional morality, human experiments are justified for the greater good of the Party and the state. Their conversation then alights on Dostoyevsky’s famous novel Crime and Punishment. Rubashov argues that the psychological downfall of the novel’s protagonist, Rodya Raskolnikov, demonstrates exactly the sort of morality system he has come to uphold, where each human life is valuable. Ivanov scorns this “Christian-humantiarian” thinking and leaves with the conviction that Rubashov is bound to capitulate and give him the confession that he has been after, for Rubashov is a “logical” person.

Part 3

In Part 3, we begin to see a dramatic shift in tone. During the third interrogation, Rubashov faces a different, more intense interrogation—this time not with Ivanov but with Gletkin. Gletkin embodies the new generation of the Party—he is cold, ruthless, and unwavering. Unlike Ivanov, Gletkin uses physical torture and relentless psychological pressure to break Rubashov.

Throughout the interrogation scene, an observation that Rubashov makes to a fellow prisoner rings clear: “We have replaced decency with logical consistency.” Gletkin's insistence on absolute obedience and his lack of a personal connection to Rubashov underscore the regime's dehumanization of its opponents and the shift from ideological debate to sheer force. Gletkin deprives Rubashov of sleep and keeps him under an intense, blinding light. He brings out a fellow inmate, Harelip, who accuses Rubashov of planning the assassination of Number One—a false accusation that is clearly meant to save Harelip’s own life. Rubashov recognizes Harelip as the son of an old professor friend of his and wonders about the lengths the Party will go to to extract confessions. He soon learns that his previous interrogator, Ivanov, has been shot to death for disagreements with the Party.

By the end of the third part of the novel, Gletkin has convinced Rubashov to sign his confession. By this point, Rubashov, physically and mentally exhausted, has no choice but to sign himself away to the Party.

At this stage, we see a clear parallel to the Soviet show trials of the late 1930s, which inspired Koestler to write the novel. Rubashov’s fate echoes that of Nikolai Bukharin, a Bolshevik leader whom Koestler admired and one of Stalin’s most prominent ideological rivals. Bukharin himself confessed to crimes that he had not committed and was sentenced to death on March 13, 1938.

The Grammatical Fiction

In the final section of the novel, called “The Grammatical Fiction”—a term that refers to a concept where an individual's personal thoughts and beliefs are influenced by the ideology imposed on them by a totalitarian regime, a world in which the idea of “I” (think Ayn Rand’s Anthem) is a grammatical fiction—Rubashov gives his final confession.

Here, he comes to terms with the futility of his previous beliefs and the corrupt nature of the Party he once served. This section is deeply introspective: Rubashov wonders whether it is worth eliminating “senseless suffering” if it means an increase in “purposeful suffering” and concludes that such an experiment does not hold up when applied to mankind. Rubashov thinks that the equation prescribed by the Party does not seem to add up: under the party system, the definition of the individual becomes one million divided by one million and denies subjective consciousness. This sort of mathematical precision when applied to human beings echoes the ruminations of Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man, who is responding to Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s idea of human mathematical precision in his utopian socialist work What Is to Be Done? The title was later borrowed by Lenin in an early pamphlet on the Revolution. Within the revolutionary spirit, human beings are reduced to the sort of mathematical precision that both Rubashov and the Underground Man refute. Human beings are not works of logical calculus. Rubashov concludes that reason alone is a “faulty compass” that culminates in great darkness.

ThemesThe Grammatical Fiction section does a great job of summarizing some of the themes that we see play out in the overall trajectory of the novel.

Individual vs. Collective

The most important theme that we see throughout the novel is the idea of the individual versus the collective, which is embodied in the idea of the grammatical fiction itself. Throughout the novel, Rubashov begins to realize the importance of the individual, and he pronounces the word “I” for the first time toward the end of the book. Rubashov eventually realizes that the Party, which he once viewed as infallible, is deeply flawed, yet following his interrogations, he has no choice but to capitulate to it.

Morality

We see Rubashov becoming painfully aware of a sort of old-guard morality system in his appeal to Raskolnikov’s moral conscience in Crime and Punishment. While Ivanov believes in what he calls “vivisectional morality,” where all human beings are meant to be experimented on for the welfare of the state, Rubashov starts to believe in the value of each individual life through an appeal to a Judeo-Christian moral conscience.

The epigraph to the third interrogation is a quote from Matthew that succinctly sums up the morality theme that runs through the third section:

“But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil.”

In this passage in the New Testament, Jesus explains that "yes" and "no" should be binding words—if you say you will do something, you should do it. The epigraph highlights the duplicitous nature of political discourse within a totalitarian regime.

Rubashov faces moral complexity and ethical decay—there are no more clear moral boundaries for what the party believes in. The party system denotes the erosion of the concepts of good and evil that have long been present in a historical Western morality system. Without an understanding of good and evil, or perhaps with a deliberate scorning of these concepts, the party is free to undertake whatever malicious actions it sees fit.

Psychological Manipulation

The dynamic between Rubashov and his interrogators, Ivanov and Gletkin, is central to the novel. Ivanov, an old friend, represents the old guard of the revolution, while Gletkin embodies the new, ruthless generation. Ivanov's interrogative approach is more philosophical, relying on psychological manipulation, whereas Gletkin uses physical torture and relentless pressure. This contrast highlights the shift in the Party's methods and the increasing dehumanization within the system. Both methods ultimately leave Rubashov feeling helpless and ready to give in.

Further Study QuestionsHow might Rubashov’s journey relate to our time?

Why must Rubashov confess to uncommitted crimes, and how does he reconcile himself to this?

What is the significance of the title Darkness at Noon?

Why does Little Löwy commit suicide?

Why does Harelip betray Rubashov?

Why does Rubashov betray Orlova?

Why is Ivanov shot to death?

Why doesn't Koestler ever identify the USSR in the book?

What is the significance of the “Grammatical Fiction”?

June 30, 2024

What is Postmodernism?

I’ve talked about several books that we might consider “postmodern.” White Noise by Don DeLillo or The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon, for instance. But what is postmodernism?

Given its purposeful elusiveness, postmodernism can be somewhat difficult to define (one of the ideas inherent in postmodernism, in fact, is the notion that words do not have stable definitions), but let’s try our best.

For one, postmodernism is a response to the value system of modernity. The writing of the the modernist literary behemoths—Joyce, Eliot, Pound, to name a few—is often characterized by a quasi-indecipherable, intellectual style and addresses the harsh reality of a decaying, modernist society through themes such as alienation, absence, and longing. Postmodernism, however, does away with such themes and aspirations and seeks to eradicate the sort of system that had previously privileged the intellectual elite.

If modernism was the cry to be understood—a futile one, at that—then postmodernism doesn’t give a f*ck. The proliferation of profanity in the postmodern mind is another one of its hallmarks, emerging as an appeal to the common man, the Other who now holds just as much relevance in society and can no longer be repressed under an older hierarchical structure created by the modernists, whose meaning was meant to be deciphered only by a select few. Modernism’s cry to be understood fades into indifference, and in postmodernism, with the death of the self, the death of the author, there is no more importance placed on whether the author cares at all to convey a certain message. Modernism's fragmented self fades into a transcendent nothing, and with this nothing, meaning can be created by just about anyone in just about any way, for words are no longer marks of stability.

Postmodernism thus breaks free of boundaries. In postmodernism, meaning lies in différance, a term popularized by the French philosopher Jacques Derrida in his seminal postmodern work Of Grammatology. If you know French, you’ll know that the word for “difference” is spelled différence in French, so why the spelling discrepancy? Well, for Derrida, différance is a play (Derrida liked those too) on the original différence that captures both the idea of “difference of meaning” and “deferral of meaning.” For Derrida, true meaning can only arise in deferral, and thus, the philosopher encourages us not to jump to conclusions in ascribing meaning to our language. Only in movement and in deferral can we eradicate the one sovereign meaning that reigns supreme above all Others. In postmodernism, the Other takes the forefront, creating a proliferation of meaning. Creativity is unleashed, and writing, through a newborn subjectivity, becomes unlimited by previous constraints of reason.

This idea of the Other also makes a frequent cameo in postmodern theory as well. A key cornerstone of postmodernism thought is “binary opposition theory,” a term first introduced by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure and later popularized by Derrida and his contemporary Claude Levi-Strauss. According to Derrida, we often obtain the meaning of a certain word in terms of binary opposition, and Derrida argues that one term often takes precedence over the other, creating a sort of intellectual hierarchy. For instance, in the binary of man/woman, man has always taken precedence over woman, and in the binary of light/dark, light has always taken precedence over dark. Derrida argues that this is an erroneous way of thinking, and his postmodern thought seeks to erode the hierarchies that prop up these binaries (Of Grammatology itself aims to undermine the speech/writing binary, arguing that writing is just as powerful as speech). Under the eradication of binary opposition theory, hierarchies fall away, and social structures are free to embody more potent systems of equality.

Because it does away with the concept of the intellectual elite, postmodernism also strives to reach a wide audience and accomplishes this feat through the age of media, representation, and simulacra. The erasure of binary pairs—and the privileging of one pair over the other—allows a multivalent culture to thrive: no longer is there a superior understanding of race, culture, or identity. We face, instead, an era of inclusion, in which everyone is always interconnected through the age of the internet: suddenly, we are able to witness and appreciate life across the ocean and create for ourselves a mélange of ideas that would have never before been possible. The proliferation of culture allows for the rapid increase of ideas and objects at a speed that would never have been possible before the advent of technology. And while postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard, in his argument that such a trend inaugurates an order of simulacra that replaces the original real, approaches this era despondently and censoriously, others have argued that there is nothing wrong with this new understanding of reality—that, in fact, it promotes a liberational culture that allows new realities to emerge. What Baudrillard calls “the simulacrum” is simply a new layer of reality that is at first daunting yet later exciting, a new era where we are not bound by previous constrictions. Postmodernism grants freedom and embraces new possibilities through the birth of the Other. Postmodernism is infinite.

Do I believe in any of this? Of course not. But it’s a cool intellectual thought experiment.

By the way Jackie Derrida, I would not exactly characterize your writing as relevant to the common man, but nice try.

June 22, 2024

One English Major’s Journey to Success

When I was graduating high school, my favorite English teacher had one piece of advice: “Don’t major in English.”

At 17, I didn’t understand his message. I felt he had my best interest in mind — he had taught my middle school humanities class when I was 12 years old and had first sparked my love of poetry through his insightful Friday morning poetry lessons — together, we had stood out in the glistering January snow reciting Wallace Stevens’ “The Snow Man” and memorized the opening stanzas to Henry Wadswroth Longfellow’s “A Psalm of Life.” He had led me through my senior year capstone project in creative writing, which had taken me to London to retrace the footsteps of my favorite authors, and he would always perk up whenever I mentioned that loved literature more than just about anything else in the entire world, a triumphant expression metastasizing on his face.

He had left me stumped. Why not study the subject I was the most passionate about?

When I bought my one-way ticket to Manhattan to attend Columbia University, surrounded by the world’s future leaders and brightest minds, I couldn’t understand why so few people cared about literature. I had expected a legion of disciples of the humanistic tradition, which is always how Columbia advertised itself historically, but on campus, the most popular major was economics, followed by political science and computer science. My social circles buzzed with the world’s future bankers, lawyers, and engineers, and each of them sneered at my desire to study English. The major was not rigorous enough, I would have no job, I would be paying off my student loans until I was 80 years old, I was wasting my Columbia education. Beneath the weight of post-college reality and cutthroat competition on campus, some of my peers in the department succumbed to the pressure: I witnessed humanities majors, one by one, switch over to one of these more “practical” majors–-or, at least, add on a more “practical” minor. But I was set on becoming a writer.

The negative feedback only snowballed from there — and once again came from people who presumably had my best interest in mind. My friends warned me about being stuck in debt for the remainder of my quixotic existence and advised me to pursue internship opportunities in the business sphere. My academic advisor suggested that I pick up a minor in economics and also extolled the merits of those same business internship opportunities. Distant relatives asked me if my life goal was to become a high school English teacher it wasn’t). I was a sort of laughing stock on campus for believing that I would make it in the professional world, armed only with my English degree and lacking a tangible backup plan. But all I knew at that stage in my life was that I was a talented writer, and I had always been told that talent and hard work will get you anywhere.

Indeed, not only did I lack a backup plan, but I also had no Plan A. I was studying English because I loved literature and writing, but as senior year crept up on me, I knew that I would need to sustain myself and my future family and make strides in my professional life. I pursued an MA in English primarily to buy myself another year of rumination and graduated with no set plan in the midst of the pandemic. With applications to many PhD programs now postponed, I knew that I could no longer hide from reality in my academic ivory tower. I was delivered my signal that the real world was beckoning.

In the intervening years, disoriented as a college graduate and disheartened by the lack of applications for my degree, I began to edit college essays from high school seniors as supplemental income while I carved out a game plan for my career. I took a job in copywriting and quit in less than a month. I interviewed for roles in asset management, real estate, and finance writing and turned down offers for all three after quickly apprehending that the corporate world was indeed not made for me (and that I was not made for it either). I continued on with my college essay editing, feeling somewhat ashamed before my peers who had been thrust directly into six-figure jobs upon graduation. I had no profession. I was still trying to make it as a writer, but the novel I had written in college was going nowhere in terms of representation or publication. I had thought that it would be easier to latch onto at least someone or something in the publishing world, but entry into the industry was not through the sort of pellucid window I had imagined. Had my peers and advisors and family members been right all along? Should I have studied something completely different or at least have taken that offer in asset management?

I kept on editing those college essays, hopping around from one college admissions firm to the next in an attempt to maximize my hourly rate; the longer I kept at it, the more I realized how valuable my editing and pedagogical skills were to the futures of these students looking to secure an education. Not only that, but my aptitude for communicating with and guiding younger students had quickly made me a standout applicant for these college admissions consulting firms, and my services saw a great increase in demand. I was working several jobs trying to make it in Manhattan — all while continuing my writerly pursuits — but I was starting to earn a decent income just from editing college essays. And that when I realized that I had been right all along about the value of my degree.

Flash forward several years. I founded a successful college essay startup based on my aptitude for writing and communication. Every day when I wake up, I don’t have to rush off to a dull office or report to an overworked boss who takes his personal failures out on his employees. I am in control of my own schedule and can choose to take vacations without anyone’s permission. I get to cherry-pick my coworkers and use my management and organizational skills to oversee the larger trajectory of my company’s growth. I employ over 20 people — some of them the same people from college who once laughed at me for studying English. I outearn my friends who studied finance, CS, and law, and because of my flexible schedule and the freedom of being your own boss, I have time to share my poems with the world through my newest venture, the Pens and Poison project. My peers look up to me for professional advice, and I’ve become a sort of bastion for unconventional success. Being an English major in the 21st century may be unpopular, but if I’ve learned anything from my experiences, it’s that if you’re good at something, you will make it in our world. There have been setbacks, but my English degree has taught me all about human interaction and communication — the secret to success.

Don’t let anyone tell you that literature is useless.

June 20, 2024

The Poetic Tradition: On Perfecting Your Craft

What can we learn from the Ancient Greeks about good writing? As it turns out, most things.

I teach creative writing to teenagers for a living. Many of these kids have never read a book in their lives, let alone heard of the Greek poet Homer—they are there to write a college essay and never write again.

But why this disdain for writing? The most probable answer I can divine has to do with fear—we know that the human experience of fear is closely intertwined with unfamiliarity: expose the monster under the bed as a mere dust bunny, and fear will evanesce. That’s what I like to do with writing. Instead of first diving into the crevices of my students’ brains to fish out memories and events that will eventually mold into their college essay topics, I start from square one: understanding writing as a craft.

My favorite poet and literary critic T.S. Eliot once said that poets are “curious explorers of the soul.” The aim of writing, according to Eliot, is to bare the soul forth through meticulously-chosen diction and syntax that will allow an unrefined emotion to sing in poetic form. For Eliot, exploring the root of the human condition had much to do with technique and craft, and indeed, the Ancient Greeks would agree.

We can trace literature’s very origins back to the oral tradition of the Ancient Greeks. Think Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad. Though we cannot be sure exactly what these epics sounded like in performance, we know that they were virtually always accompanied by some form of music—or at least sung aloud. For the Ancient Greeks, therefore, literature and music were virtually indistinguishable. In fact, the second word of the opening line of Homer’s Iliad is ἄειδε or “sing,” highlighting the importance of music in the Greek epic tradition. We might therefore think of storytelling—and the art of writing that this tradition eventually culminated in—as a musical art form. Arguably more important than the message of a particular piece of literature is the way it sounds. That’s something I always ask my students: does your writing sound good when read aloud?

We can use the poetic tradition as a paragon for strong, literary writing. Up until the 17th century, in fact, virtually all literature was written in poetic rather than prose form—our word “prosaic,” which means ordinary or dull, stems from the word “prose,” a mode of writing that was largely reserved for official documents or other non-artistic record-keeping. The invention of the novelistic form in the 17th century introduced the idea that beautiful writing could depart from poetry, yet this sort of early prose writing retained some of the principles that characterized our beautiful poetic tradition: attention to tone, style, craft.

So what’s all this about craft? We can think of craft, generally, as the techniques we use to help a piece of writing come to life. The Greeks have given us several terms to work with as well as we begin to conceptualize “craft” in writing. Here are a few terms to consider:

Τέχνη (techne): Skill in making or doing. This is where we get our English word “technical.”

Ποίησις (poiesis): The art of bringing something into being that did not exist before. This is where we get the word “poetry.”

Ἀλήθεια (aletheia): Truth. This is also the word that Plato uses in Book 7 of the Republic during the famous cave episode.

In his exploration of the theory of art, German philosopher Martin Heidegger borrowed the first two terms—techne and poiesis—and argued that techne, the craft of one’s art, brings poiesis into being. It is through the mastery of the technical form that art is created—that poetry is made. Poiesis, in turn, culminates in the revelation of one’s authentic truth or aletheia. (Heidegger likens aletheia here to his monumental concept of Eigentlichkeit, or authenticity, which he explores in depth throughout his philosophical behemoth Being and Time. We won’t delve much into Heidegger here (though I do encourage you to check him out), but we can learn a lot from this nugget of philosophy from the German master: developing a specific craft or technical process (techne) is crucial to the transmission of an authentic story through the poetic tradition.

So what are some of the important elements of literary craft? I’ll leave you today with a few definitions of literary terms:

Diction: This is the choice of words or vocabulary that a writer uses to convey a certain message. Diction creates the tone of a piece of writing.

Tone: This is the overall “feel” of the piece or a writer’s attitude towards a certain subject.

Syntax: This is the way that words are arranged within a sentence to create a cohesive whole.

Writing is fairly easy if you know what to look for. You can ask yourself three questions as you begin to perfect your craft:

Is my use of words deliberate?

How am I arranging those words?

What is the overall feel of my piece as informed by those two elements?

And—most importantly—does your writing sound good when read aloud?

You might not be writing a college essay like the kids I annoy every September with the college essay process, but I hope that you’ll remember a thing or two about good writing as you embark on your next literary project: good writing is, at its core, technically accomplished and musically profound.

June 17, 2024

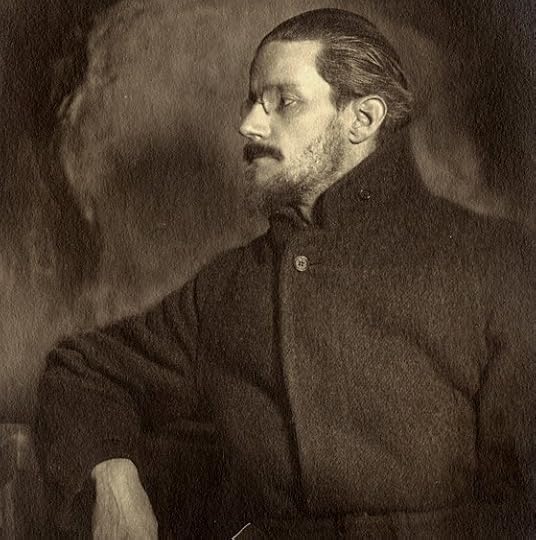

Weekly Literary Spotlight: James Joyce

James Joyce, an iconic figure in 20th-century literature, revolutionized the way we understand narrative and language. His works, complex and formidable, have challenged the minds of generations of readers and scholars. In this week’s Literary Spotlight, we review Joyce’s life, his distinctive literary style, and a handful of his most significant works.

Joyce, c. 1918

Life Overview:

Born on February 2, 1882, in Dublin, Ireland as the eldest of ten siblings, Joyce grew up in a family that experienced significant financial difficulties due to his father's poor financial management. Despite these early hardships, Joyce excelled academically and attended University College Dublin, where he studied modern languages.

In 1904, Joyce met Nora Barnacle, a young woman from Galway who would later become his wife. The same year, Joyce left Ireland for what would become a permanent exile, living in cities like Zurich, Trieste, and Paris. His years abroad were marked by both literary productivity and personal challenges, including struggles with poverty, censorship, and his daughter's mental health issues.

Joyce's life was defined by a relentless pursuit of artistic integrity. He was often at odds with the conventions of his time, both socially and artistically. Despite this, he remained committed to his vision, producing works that would come to define modernist literature. Joyce passed away on January 13, 1941, in Zurich, but his legacy flourishes through his groundbreaking contributions to literature.

Stylistic Overview:

Joyce's literary style is characterized by its innovation and complexity. He is perhaps best known for his use of stream-of-consciousness, a narrative technique that seeks to capture the flow of thoughts and feelings in a character's mind without inhibitions. This technique allows readers to experience the inner workings of characters' minds in a way that mimics natural thought processes, often resulting in fragmented and nonlinear narratives.

Another hallmark of Joyce's style is his linguistic experimentation. He played with language in ways that challenged traditional grammar and syntax, incorporating multilingual puns, allusions, and invented words. This approach requires readers to actively engage with the text in order to decipher its messages.

Joyce's work is also notable for its dense intertextuality. He drew on a vast array of sources, including mythology, history, religion, and literature, and wove them into the fabric of his narratives. This layering of references creates a rich tapestry of meaning that encourages multiple interpretations and re-readings.

Notable Works:

Dubliners (1914): A collection of 15 short stories that depict the everyday lives of Dublin's residents. Each story captures moments of epiphany, revealing the characters' inner realities and the broader social and cultural context of early 20th-century Ireland. The collection's straightforward prose and penetrating observation of human nature make it accessible yet profound.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916): A semi-autobiographical novel that follows the development of Stephen Dedalus, a young man grappling with his identity, faith, and artistic calling. The novel's innovative use of stream-of-consciousness and its exploration of the artist's role in society have made it a pioneering work of modernist literature.

Ulysses (1922): Joyce's magnum opus; a sprawling, epic novel that parallels Homer's Odyssey in its structure and themes. Set over the course of a single day, June 16, 1904, the novel follows the lives of Leopold Bloom, Stephen Dedalus, and Molly Bloom in Dublin. Despite initially facing censorship and controversy, it has since been hailed as one of the greatest literary works of all time.

Joyce’s tumultuous yet artistically abundant life, his revolutionary stylistic approaches, and his seminal works have cemented his place as a literary giant. His legacy continues to challenge and inspire readers, ensuring that his impact on literature will thrive for generations to come.