P.J. Berman's Blog, page 6

November 24, 2019

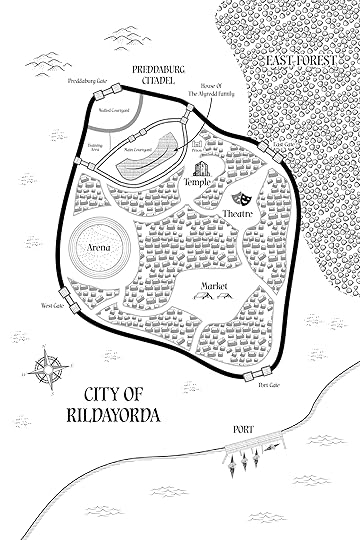

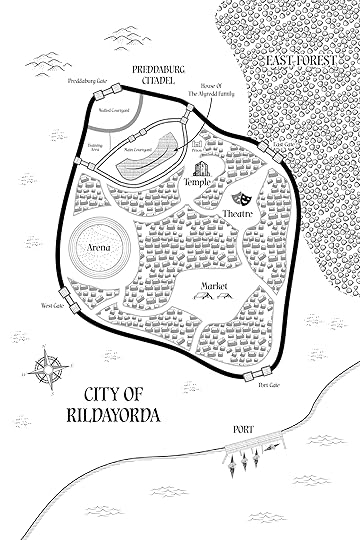

Rildayorda - A Portrait of a City

Rildayorda is a Bennvikan city. It also functions as the provincial capital of Bastalf.

Hentani Origins:

When the Hentani settled in the south after their eviction from Hazgorata in 612 BU, they built a large camp near the coast. As was the Hentani way at the time, this consisted of a large number of wide, squat, gers surrounded by a huge fence of wooden stakes.

However, this new settlement, then named Jianoko, was different from any previous Hentani camps due to its sheer size. It was a city of gers, over a mile in diameter. The only Hentani settlements that would ever even approach this size would be Quesoto and Imako, far to the west, but these would not be founded for some years.

Over the centuries, with the tribe establishing a sense of permanence to their dwellings, this large fence was replaced by a wooden wall, which in turn was later replaced by a much taller one of stone. The gers would go on to be removed to make way for wooden houses and large public buildings, and the grass was covered over by cobbled streets.

Siege, Conquest and a New Identity:

Jianoko was successfully besieged by Bennvikan forces in 1501, and after it fell, its new owners immediately set about Bennvikanising the city. They began by rebranding the city 'Rildayorda', meaning 'The City of the Wilds'.But the changes didn't end with a new name. The walls were reinforced and updated, and open sewers were introduced to the city streets where previously there had been none.

Upon the hill overlooking Rildayorda, work began on what would become the mighty Preddaberg Citadel, now the home of the Alyredd family, while down by the sea, the abandoned fishing village, vacated by its inhabitants at the beginning of the siege, was developed into an enormous port.

The Temple of Lomatteva and Bertakaevey:

Perhaps the most famous legacy of the Bennvikan colonisation of Rildayorda is its temple. This is thought to have been the second new building to be commissioned after the invasion. The first, perhaps rather tellingly, was the City Prison.

The project surrounding the temple's construction, as much a diplomatic one as a religious one, was the brainchild of the city's first Bennvikan governor, Lord Yathrud Alyredd, who had personally taken part in the siege. He was well aware that, although they were ostensibly defeated, the Hentani still represented the vast majority of the city's population, and to keep them under control, he would have to keep them happy.

The building of the temple was Alyredd's masterstroke. By muddying the waters and making two distinct religions appear to many as two sects of the same religion, at least on a local level, he managed to ease the tensions between the Bennvikan and Hentani factions in his city in the seventeen years since the temple broke ground and the present day.

The Rildayorda City Theatre:

For any traveller walking through Rildayorda intending on indulging in some sighteeing, there is something of a 'big three' on any visitor's list. If the Temple of Lomatteva and Bertakaevey is the first, then the Rildayorda City Theatre is most certainly the second.

This state-of-the-art building features everything a modern theatre-goer could wish for, as well as a design based on the famous Zevarium Theatre in the hills outside Gorgreb, Verusantium (pictured above).

At the Rildayorda City Theatre, a whole range of comedies, tragedies and satyrs are played out at this dramatic open-air venue, and you can even buy a cup of only partially-watered wine for less than two fedrukas.

Rildayorda Gladiatorial Arena:

The third major must-see building in Rildayorda is by far the oldest, the Rildayorda Gladiatorial Arena, affectionately known to the locals as 'Halbrod Lane', in referance to the street that runs past it. Unlike the tample and the theatre, this building pre-dates the Bennvikan invasion by some decades, but in the days since then, its popularity has risen to hights never imagined during the Hentani era.

This wooden stadium may be a faction of the size of the giant stone venues of Kriganheim, but for any die-hard gladiator fan, there is nothing like a traditional, sand-base arena like this one, where you can get so close to the action that you can almost taste the spilt blood.

Artwork - (Top to bottom) 'Rildayorda City Map' by Oliver Bennett at More Visual Ltd, 'The Parthenon' by Thomas Djalloul at Artstation, 'Ancient Greek Inspired Theatre' by Tom Moore at Artstation and 'Gladiator Arena' by Nikola Damjanov at Artstation.

Hentani Origins:

When the Hentani settled in the south after their eviction from Hazgorata in 612 BU, they built a large camp near the coast. As was the Hentani way at the time, this consisted of a large number of wide, squat, gers surrounded by a huge fence of wooden stakes.

However, this new settlement, then named Jianoko, was different from any previous Hentani camps due to its sheer size. It was a city of gers, over a mile in diameter. The only Hentani settlements that would ever even approach this size would be Quesoto and Imako, far to the west, but these would not be founded for some years.

Over the centuries, with the tribe establishing a sense of permanence to their dwellings, this large fence was replaced by a wooden wall, which in turn was later replaced by a much taller one of stone. The gers would go on to be removed to make way for wooden houses and large public buildings, and the grass was covered over by cobbled streets.

Siege, Conquest and a New Identity:

Jianoko was successfully besieged by Bennvikan forces in 1501, and after it fell, its new owners immediately set about Bennvikanising the city. They began by rebranding the city 'Rildayorda', meaning 'The City of the Wilds'.But the changes didn't end with a new name. The walls were reinforced and updated, and open sewers were introduced to the city streets where previously there had been none.

Upon the hill overlooking Rildayorda, work began on what would become the mighty Preddaberg Citadel, now the home of the Alyredd family, while down by the sea, the abandoned fishing village, vacated by its inhabitants at the beginning of the siege, was developed into an enormous port.

The Temple of Lomatteva and Bertakaevey:

Perhaps the most famous legacy of the Bennvikan colonisation of Rildayorda is its temple. This is thought to have been the second new building to be commissioned after the invasion. The first, perhaps rather tellingly, was the City Prison.

The project surrounding the temple's construction, as much a diplomatic one as a religious one, was the brainchild of the city's first Bennvikan governor, Lord Yathrud Alyredd, who had personally taken part in the siege. He was well aware that, although they were ostensibly defeated, the Hentani still represented the vast majority of the city's population, and to keep them under control, he would have to keep them happy.

The building of the temple was Alyredd's masterstroke. By muddying the waters and making two distinct religions appear to many as two sects of the same religion, at least on a local level, he managed to ease the tensions between the Bennvikan and Hentani factions in his city in the seventeen years since the temple broke ground and the present day.

The Rildayorda City Theatre:

For any traveller walking through Rildayorda intending on indulging in some sighteeing, there is something of a 'big three' on any visitor's list. If the Temple of Lomatteva and Bertakaevey is the first, then the Rildayorda City Theatre is most certainly the second.

This state-of-the-art building features everything a modern theatre-goer could wish for, as well as a design based on the famous Zevarium Theatre in the hills outside Gorgreb, Verusantium (pictured above).

At the Rildayorda City Theatre, a whole range of comedies, tragedies and satyrs are played out at this dramatic open-air venue, and you can even buy a cup of only partially-watered wine for less than two fedrukas.

Rildayorda Gladiatorial Arena:

The third major must-see building in Rildayorda is by far the oldest, the Rildayorda Gladiatorial Arena, affectionately known to the locals as 'Halbrod Lane', in referance to the street that runs past it. Unlike the tample and the theatre, this building pre-dates the Bennvikan invasion by some decades, but in the days since then, its popularity has risen to hights never imagined during the Hentani era.

This wooden stadium may be a faction of the size of the giant stone venues of Kriganheim, but for any die-hard gladiator fan, there is nothing like a traditional, sand-base arena like this one, where you can get so close to the action that you can almost taste the spilt blood.

Artwork - (Top to bottom) 'Rildayorda City Map' by Oliver Bennett at More Visual Ltd, 'The Parthenon' by Thomas Djalloul at Artstation, 'Ancient Greek Inspired Theatre' by Tom Moore at Artstation and 'Gladiator Arena' by Nikola Damjanov at Artstation.

Published on November 24, 2019 22:00

November 17, 2019

The Second Hentani War

The Second Hentani War (1500-1503) can be more accurately described as the invasion of the Hentani Kingdom by Bennvika. After much bloodshed, the war ended when the Hentani Kingdom collapsed.

The Road to War:

A leader’s duty is to keep their people safe. In the mind of King Bastinian of Bennvika, known by some as Bastinian the Great and by others as Bastinian the Wicked, the best way to do this was to expand Bennvika’s borders, so that they kingdom may be feared by its neighbours.

The natural target was the Hentani Kingdom. The population of Bennvika had never quite forgotten the Hentani’s attempt to invade southern Bennvika in the First Hentani War (1236-37 AU), back in the days of King Ansdren and Chief Rokujo.

In an attempt to rally the support of the nobles and win control of an increasingly impetuous Congressate, King Bastinian ordered the raising of an army.He did this publicly during his speech at the 1500th Bennvikan Unification Day, an event celebrating 1500 years since the kingdom’s inception.It is believed by many that he hadn’t told anyone that he was planning on making this announcement. There was much surprise from the nobles, but none dared challenge the king, especially after witnessing the strength of the crowd’s support.

First Engagements:

The Hentani Prince Vorad, son of the then Cheif, Goyro, and heir to the tribe’s throne, led the defence of their kingdom, although with his father still retaining ultimate authority.Anticipating that the Bennvikans would go straight for the heart of the kingdom, Vorad oversaw the preparations for his father’s capitol, Jianoko, to defend a siege.

This was the first moment at which the war went against the Hentani. After initially marching towards Jianoko, now known as Rildayorda, Prince Lissoll of Bennvika then swing west, heading for the Hentani city of Quesoto. When news of this was fed back to Vorad, he was presented with a problem.

Vorad saw through Lissoll’s trick, knowing that that it was simply an attempt to lure the main Hentani army out from within the safe protection of Jianoko’s defences. The more recent Preddaberg Citadel has not yet been built, but with its stone walls, the city would still have been a tough nut for the Bennvikans to crack.However, keeping the main army in Jianoko left the other cities vulnerable, and reports came flooding in telling of many towns being reduced to burning ruins.

Vorad soon saw his cautious policy overruled by his father Chief Goyro, and he was ordered, despite much protesting from Vorad himself, to take the army out of the city, march west and meet the Bennvikans of the field of battle.

The Battle of Repuki and the Fall of Jianoko:

Despite Cheif Goyro’s visions of a decisive, bloody engagement, the Battle of Repuki was something quite else, and the indecisive result saw Vorad’s force, battered as it was, live to fight another day.

The Lissoll had been made aware of the Hentani advance by his scouts and, acting on the advice of Yathrud Alyredd, a commander of growing reputation, took up a defensive position at the top of a suitable incline, and waited for Vorad’s force to come to him.

The orders from Vorad's father gave him no choice but to fight, but from the moment the battle began, the Hentani army took heavy losses and were put to flight by their better trained Bennvikan foe. Yet Vorad though fast when he saw so many of his warriors turning and running. He ordered his army's war horns be blown.

Heartened by the sound, some of the Hentani troops heard this and relised that although the battle was lost, a small contingent had managed to retreat in good order to the east, too weak to take on the Bennvikans again that day, but strong enough to march away and lick their wounds.

After the defeat at Repuki, Vorad was very much aware that, rather than pursuing him east, the Bennvikans headed south, going for the jugular and heading straight for Jianoko. But he knew that followign them would be suicide, such was the weakness of his remaining force, even with the addition of those few men who had heard his war horns and regrouped with his force after the battle.

So he made the hard decision to leave the garrison commanded by his father to defend the city, while Vorad himself headed west to Quesoto in the hope of raising a larger force with which he could then march on Jianoko and defeat the Bennvikans with his relief force.However, the vastly outnumbered Jianoko garrison was unwilling to fight when the Bennvikans arrived. There was a mutiny. The ringleaders opened the gates in capitulation with the Bennvikans, and handed Chief Goyro over to them.

The Second Stage:

After taking Jianoko in the autumn of 1501, Prince Lissoll of Bennvika wintered there. When hostilities were resumed in the spring of 1502, he ordered Yathrud Alyredd to stay in the city to oversee its pacification and it’s population’s assimilation into the Bennvikan way of life.

Without Yathrud to restrain him, the hot-headed young Lissoll became increasingly violent towards any Hentani settlements that fell into his hands, frustrated by slow progress as his advance was handicapped by Vorad’s scorched earth tactics.

Nevertheless, ignoring the deadly chaos that had been unleashed in all its fury on the vulnerable, defenceless towns and villages, the newly-crowned Chief Vorad stayed with his army within the confinces of Quesoto's walls, where he soon found himself beseiged by Lissoll.

The Siege of Quesoto:

What Vorad didn't know was that Lissoll had sent a second force north to besiege Imako. After hearing the rumours that Imako, like Jianoko, had surrendered without a fight, morale inside Quesoto hit a new low.

Then the Hentani were hit with another hammer-blow. Vorad fell during intense fighting with the Bennvikans as they tried to storm the city walls.

Mourning Vorad, much of the army lost their stomach for the fight. With Vorad’s death, his son, a boy named Hojorak, was named as chief. He sent an emissary to Lissoll. What the Hentani didn't know was that the Bennvikan army was on the verge of mutiny over unpaid soldiers' wages.

If they had held out at Quesoto for a few more days or weeks, perhaps they would have emerged victorious? Such are the 'ifs' and 'buts' of history.

As it was, without this knowledge, the new Chief Hojorak had handed Prince Lissoll a priceless opportunity. By sending the emissary with terms of the Hentani's surrender, handing all Hentani lands over to the Bennvikan crown on the condition that the Hentani themselves could continue to live in them in peace, he had presented the resolution Lissoll so desperately needed.

Lissoll got to walk away with his victory and the loot and glory from his conquest, and with his authority over his army revitalised, while the Hentani got to survive.As a footnote, from that moment, Chiefdom of the Hentani became a client-king position to the Bennvikan throne.

The Road to War:

A leader’s duty is to keep their people safe. In the mind of King Bastinian of Bennvika, known by some as Bastinian the Great and by others as Bastinian the Wicked, the best way to do this was to expand Bennvika’s borders, so that they kingdom may be feared by its neighbours.

The natural target was the Hentani Kingdom. The population of Bennvika had never quite forgotten the Hentani’s attempt to invade southern Bennvika in the First Hentani War (1236-37 AU), back in the days of King Ansdren and Chief Rokujo.

In an attempt to rally the support of the nobles and win control of an increasingly impetuous Congressate, King Bastinian ordered the raising of an army.He did this publicly during his speech at the 1500th Bennvikan Unification Day, an event celebrating 1500 years since the kingdom’s inception.It is believed by many that he hadn’t told anyone that he was planning on making this announcement. There was much surprise from the nobles, but none dared challenge the king, especially after witnessing the strength of the crowd’s support.

First Engagements:

The Hentani Prince Vorad, son of the then Cheif, Goyro, and heir to the tribe’s throne, led the defence of their kingdom, although with his father still retaining ultimate authority.Anticipating that the Bennvikans would go straight for the heart of the kingdom, Vorad oversaw the preparations for his father’s capitol, Jianoko, to defend a siege.

This was the first moment at which the war went against the Hentani. After initially marching towards Jianoko, now known as Rildayorda, Prince Lissoll of Bennvika then swing west, heading for the Hentani city of Quesoto. When news of this was fed back to Vorad, he was presented with a problem.

Vorad saw through Lissoll’s trick, knowing that that it was simply an attempt to lure the main Hentani army out from within the safe protection of Jianoko’s defences. The more recent Preddaberg Citadel has not yet been built, but with its stone walls, the city would still have been a tough nut for the Bennvikans to crack.However, keeping the main army in Jianoko left the other cities vulnerable, and reports came flooding in telling of many towns being reduced to burning ruins.

Vorad soon saw his cautious policy overruled by his father Chief Goyro, and he was ordered, despite much protesting from Vorad himself, to take the army out of the city, march west and meet the Bennvikans of the field of battle.

The Battle of Repuki and the Fall of Jianoko:

Despite Cheif Goyro’s visions of a decisive, bloody engagement, the Battle of Repuki was something quite else, and the indecisive result saw Vorad’s force, battered as it was, live to fight another day.

The Lissoll had been made aware of the Hentani advance by his scouts and, acting on the advice of Yathrud Alyredd, a commander of growing reputation, took up a defensive position at the top of a suitable incline, and waited for Vorad’s force to come to him.

The orders from Vorad's father gave him no choice but to fight, but from the moment the battle began, the Hentani army took heavy losses and were put to flight by their better trained Bennvikan foe. Yet Vorad though fast when he saw so many of his warriors turning and running. He ordered his army's war horns be blown.

Heartened by the sound, some of the Hentani troops heard this and relised that although the battle was lost, a small contingent had managed to retreat in good order to the east, too weak to take on the Bennvikans again that day, but strong enough to march away and lick their wounds.

After the defeat at Repuki, Vorad was very much aware that, rather than pursuing him east, the Bennvikans headed south, going for the jugular and heading straight for Jianoko. But he knew that followign them would be suicide, such was the weakness of his remaining force, even with the addition of those few men who had heard his war horns and regrouped with his force after the battle.

So he made the hard decision to leave the garrison commanded by his father to defend the city, while Vorad himself headed west to Quesoto in the hope of raising a larger force with which he could then march on Jianoko and defeat the Bennvikans with his relief force.However, the vastly outnumbered Jianoko garrison was unwilling to fight when the Bennvikans arrived. There was a mutiny. The ringleaders opened the gates in capitulation with the Bennvikans, and handed Chief Goyro over to them.

The Second Stage:

After taking Jianoko in the autumn of 1501, Prince Lissoll of Bennvika wintered there. When hostilities were resumed in the spring of 1502, he ordered Yathrud Alyredd to stay in the city to oversee its pacification and it’s population’s assimilation into the Bennvikan way of life.

Without Yathrud to restrain him, the hot-headed young Lissoll became increasingly violent towards any Hentani settlements that fell into his hands, frustrated by slow progress as his advance was handicapped by Vorad’s scorched earth tactics.

Nevertheless, ignoring the deadly chaos that had been unleashed in all its fury on the vulnerable, defenceless towns and villages, the newly-crowned Chief Vorad stayed with his army within the confinces of Quesoto's walls, where he soon found himself beseiged by Lissoll.

The Siege of Quesoto:

What Vorad didn't know was that Lissoll had sent a second force north to besiege Imako. After hearing the rumours that Imako, like Jianoko, had surrendered without a fight, morale inside Quesoto hit a new low.

Then the Hentani were hit with another hammer-blow. Vorad fell during intense fighting with the Bennvikans as they tried to storm the city walls.

Mourning Vorad, much of the army lost their stomach for the fight. With Vorad’s death, his son, a boy named Hojorak, was named as chief. He sent an emissary to Lissoll. What the Hentani didn't know was that the Bennvikan army was on the verge of mutiny over unpaid soldiers' wages.

If they had held out at Quesoto for a few more days or weeks, perhaps they would have emerged victorious? Such are the 'ifs' and 'buts' of history.

As it was, without this knowledge, the new Chief Hojorak had handed Prince Lissoll a priceless opportunity. By sending the emissary with terms of the Hentani's surrender, handing all Hentani lands over to the Bennvikan crown on the condition that the Hentani themselves could continue to live in them in peace, he had presented the resolution Lissoll so desperately needed.

Lissoll got to walk away with his victory and the loot and glory from his conquest, and with his authority over his army revitalised, while the Hentani got to survive.As a footnote, from that moment, Chiefdom of the Hentani became a client-king position to the Bennvikan throne.

Published on November 17, 2019 22:00

November 11, 2019

The Art of Translation - Jennifer Silva

Hello all,

Today is interview day, and we will be getting to know Jennifer Silva, the translator who has very kindly agreed to help me bring Vengeance of Hope to the Brazilian and Portuguese public.

PB: So, Jennifer, welcome to pjbermanbooks.com. What made you decide to become a translator?

JS: I decided to become a translator because I always had a passion for books and the English language. There wasn't a moment in my day that I haven't a book in my hands, traveling for the pages wherever I was, or listening to music and trying to understand what the singer was saying, and translating the song, watching tv shows in English. So during the High School, I decided that I will work in a area where I could read books and translating them.

PB: Tell us a bit about your background and hometown.

JS: I finished my college of Letters this year, specific in Portuguese and English. I'm also finished my course of introduction. Three days on a week I give classes in a English course. My hometown is Rio de Janeiro, I love my city, the people here are very hospitable and funny. I grow up in a neighbourhood that the kids played on the streets of hide and seek and watched cartoons after school. I have an amazing nostalgia always when I think about that time.

PB: What was your first translator job?

JS: My first translator job was translating academic texts for my college.

PB: What is your favourite fiction genre and why?

JS: My favourite fiction genre is fantasy. I will try to explain that talking about my favourite book called The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. The plot has everything you want to read and find out in a book, an amazing principal character, tragedies, drama, romance, adventure and so much more. You can't stop to read until you get in the end of the book. That’s why I love fantasy, they are addictive and engaging.

PB: Tell us a bit about the process that went into translating Vengeance of Hope into Portuguese.

JS: The process is a bit long but very satisfactory in the end. I start reading all the page, then I start to translate for paragraphs and when I finished to translate the entire page, I start to review and edit, analysing the orthography. When I realize that the text is ready, I go to the next page.

PB: If your weren't a translator, what career would you be in?

JS: If I wasn't a translator I would be an English teacher.

PB: How do you spend your time when you're not translating?

JS: When I'm not translating I like to read and do reviews to the blogs that I administer with my friend called Coleções Literárias and The Nerd Kingdom, I also watch TV shows and movies, and go out with my friends and family.

PB: What are your long term ambitions career-wise?

JS: Someday I'd do my Master's and Ph.D. in Translation and maybe I'd travel to the US and Europe to attend major conventions in the universe of books and translation.

PB: What's next for you?

JS: Specializing more in translation area and continue to translating books for Babelcube.

PB: And finally, tell us a random fact about yourself.

JS: A random fact about myself is that I love drawing from an early age, and I do it sometimes when I miss it.

Thank you so much Jennifer for speaking to us today. It has been fantastic working with you.

Don't forget to look out for Vengeance of Hope, or A Espera de Vinganca, as it will be known in Portuguese, which will soon be available on Amazon, Saraiva and Submarino, as well as on many other platforms.

See you next time!

Peter

Today is interview day, and we will be getting to know Jennifer Silva, the translator who has very kindly agreed to help me bring Vengeance of Hope to the Brazilian and Portuguese public.

PB: So, Jennifer, welcome to pjbermanbooks.com. What made you decide to become a translator?

JS: I decided to become a translator because I always had a passion for books and the English language. There wasn't a moment in my day that I haven't a book in my hands, traveling for the pages wherever I was, or listening to music and trying to understand what the singer was saying, and translating the song, watching tv shows in English. So during the High School, I decided that I will work in a area where I could read books and translating them.

PB: Tell us a bit about your background and hometown.

JS: I finished my college of Letters this year, specific in Portuguese and English. I'm also finished my course of introduction. Three days on a week I give classes in a English course. My hometown is Rio de Janeiro, I love my city, the people here are very hospitable and funny. I grow up in a neighbourhood that the kids played on the streets of hide and seek and watched cartoons after school. I have an amazing nostalgia always when I think about that time.

PB: What was your first translator job?

JS: My first translator job was translating academic texts for my college.

PB: What is your favourite fiction genre and why?

JS: My favourite fiction genre is fantasy. I will try to explain that talking about my favourite book called The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. The plot has everything you want to read and find out in a book, an amazing principal character, tragedies, drama, romance, adventure and so much more. You can't stop to read until you get in the end of the book. That’s why I love fantasy, they are addictive and engaging.

PB: Tell us a bit about the process that went into translating Vengeance of Hope into Portuguese.

JS: The process is a bit long but very satisfactory in the end. I start reading all the page, then I start to translate for paragraphs and when I finished to translate the entire page, I start to review and edit, analysing the orthography. When I realize that the text is ready, I go to the next page.

PB: If your weren't a translator, what career would you be in?

JS: If I wasn't a translator I would be an English teacher.

PB: How do you spend your time when you're not translating?

JS: When I'm not translating I like to read and do reviews to the blogs that I administer with my friend called Coleções Literárias and The Nerd Kingdom, I also watch TV shows and movies, and go out with my friends and family.

PB: What are your long term ambitions career-wise?

JS: Someday I'd do my Master's and Ph.D. in Translation and maybe I'd travel to the US and Europe to attend major conventions in the universe of books and translation.

PB: What's next for you?

JS: Specializing more in translation area and continue to translating books for Babelcube.

PB: And finally, tell us a random fact about yourself.

JS: A random fact about myself is that I love drawing from an early age, and I do it sometimes when I miss it.

Thank you so much Jennifer for speaking to us today. It has been fantastic working with you.

Don't forget to look out for Vengeance of Hope, or A Espera de Vinganca, as it will be known in Portuguese, which will soon be available on Amazon, Saraiva and Submarino, as well as on many other platforms.

See you next time!

Peter

Published on November 11, 2019 06:54

November 10, 2019

The Eviction of the Hentani from Hazgorata

The Hentani Eviction from Hazgorata was a major turning point and watershed moment in ancient pre-Bennvikan history, over 2,600 years before the days of Silrith Alfwyn.

Ancient Origins:

It is unknown just how far back the bad blood between Bennvika can the Hentani tribe goes. It certainly predates the unification of Bennvika and was well established by 612 BU (before unification), with much tension between the Hentani and the Kingdom of Hazgorata, which would go on to become one of Bennvika’s two founding provinces.

According to legend, the various tribes inhabiting this area formed into two separate confederations. One of these - the Hazgoratans - was formed out of the tribes inhabiting what is now eastern Hazgorata, and the other - the Hentani - was an alliance of those tribes inhabiting the west.

Beyond this, little is known for sure, and the myths vary, but the one thing that all can agree on is that until 612 BU, neither side could destroy the other.

Sedrunna Ironhammer:

Sedrunna Ironhammer was crowned Queen of Hazgorata in 619 BU. One of the few queens to have personally lead her troops in battle, she ranks alongside the great Silrith Alfwyn as one of history's most iconic, and in Ironhammer's case, notorious, military leaders.

The suffix to her name comes from the irreversible hammer blow she inflicted on the Hentani, displacing them entirely from a land that they’d held for more centuries than history has been able to record.

The Battle of Baezia 612 BU

In the late seventh century before unification, war chariots where state-of-the-art-technology, and they would prove to be decisive at Baezia. Both armies were equipped with these wooden, archer-carrying death carts, so it is no surprise that in Hazgorata’s otherwise undulating terrain, it was on the flat, open ground of Baezia field that the two armies met.

Yet when Ironhammer’s force presented for battle their light, fast chariots were nowhere to be seen. Taking this as a sign of weakness and bad planning, the committee of Hentani leaders ordered a full attack, while Ironhammer took a wholly defensive stance. That was until smoke was seen coughing up into the air from some miles behind the Hentani force.

Far from not being at Ironhammer’s disposal, the Hazgoratan chariots had ridden some miles to the north in an arc, before swinging south to hit the Hentani camp and cutting down the warriors’ kin amid great slaughter. The sight of the smoke that belied the fate of their families caused the Hentani line to falter, and eventually rout, pursued for hours, then days by the victorious Bennvikans.

Countless tribesmen were picked off by the Hazgoratan chariots when they joined the fray in earnest, but many of the Hentani escaped. It was the beginning of the displacement of an entire civilisation. In their desperate search for refuge, the Hentani’s headlong flight south had begun.

The Founding of the Hentani Kingdom:

The Hentani had never been a fully united force while in the north. They were still a confederacy of smaller tribes, with no singular figurehead, and much bickering between the various tribal chiefs.

The Hazgoratans, meanwhile, had been subject to no such indecision as by the time of the coronation of Sedrunna Ironhammer, the crown had absolute power in her lands. Although its borders did not reach as far as they do now, Hazgorata was by then a kingdom in every way, a far cry from its beginnings as an alliance of separate factions.

Seeing this as a deciding factor in the war, and with a feeling of a lack of leadership as the tribe moved ever southward, keen to get as far out of the reach of the marauding Hazgoratans as possible, many decided that a 'Chief of Chiefs' was needed.

Into this void stepped a petty Hentani leader by the name of Taruzoc. Taruzoc, already fifty-seven years of age it this time, had been headman on the village of Haruko prior to Sedrunna Ironhammer’s purge of the Hentani from their ancestral lands. He came to be one of the loudest and most persistent voices favouring the election of a new leader to bring a clear direction to the Hentani’s future.

The reason he backed this so publicly was simple - he’d spent the entire campaign up to that point making positive political connections with other tribal leaders so that they would back his calls for a vote, and when it came to it, would back his own claim to the position.

His plan could not have worked any better, and in the opening weeks of 611 AU, Taruzoc was crowned as the first Chief of all the Hentani, formally uniting them as one singlaur tribe in the process.

Ancient Origins:

It is unknown just how far back the bad blood between Bennvika can the Hentani tribe goes. It certainly predates the unification of Bennvika and was well established by 612 BU (before unification), with much tension between the Hentani and the Kingdom of Hazgorata, which would go on to become one of Bennvika’s two founding provinces.

According to legend, the various tribes inhabiting this area formed into two separate confederations. One of these - the Hazgoratans - was formed out of the tribes inhabiting what is now eastern Hazgorata, and the other - the Hentani - was an alliance of those tribes inhabiting the west.

Beyond this, little is known for sure, and the myths vary, but the one thing that all can agree on is that until 612 BU, neither side could destroy the other.

Sedrunna Ironhammer:

Sedrunna Ironhammer was crowned Queen of Hazgorata in 619 BU. One of the few queens to have personally lead her troops in battle, she ranks alongside the great Silrith Alfwyn as one of history's most iconic, and in Ironhammer's case, notorious, military leaders.

The suffix to her name comes from the irreversible hammer blow she inflicted on the Hentani, displacing them entirely from a land that they’d held for more centuries than history has been able to record.

The Battle of Baezia 612 BU

In the late seventh century before unification, war chariots where state-of-the-art-technology, and they would prove to be decisive at Baezia. Both armies were equipped with these wooden, archer-carrying death carts, so it is no surprise that in Hazgorata’s otherwise undulating terrain, it was on the flat, open ground of Baezia field that the two armies met.

Yet when Ironhammer’s force presented for battle their light, fast chariots were nowhere to be seen. Taking this as a sign of weakness and bad planning, the committee of Hentani leaders ordered a full attack, while Ironhammer took a wholly defensive stance. That was until smoke was seen coughing up into the air from some miles behind the Hentani force.

Far from not being at Ironhammer’s disposal, the Hazgoratan chariots had ridden some miles to the north in an arc, before swinging south to hit the Hentani camp and cutting down the warriors’ kin amid great slaughter. The sight of the smoke that belied the fate of their families caused the Hentani line to falter, and eventually rout, pursued for hours, then days by the victorious Bennvikans.

Countless tribesmen were picked off by the Hazgoratan chariots when they joined the fray in earnest, but many of the Hentani escaped. It was the beginning of the displacement of an entire civilisation. In their desperate search for refuge, the Hentani’s headlong flight south had begun.

The Founding of the Hentani Kingdom:

The Hentani had never been a fully united force while in the north. They were still a confederacy of smaller tribes, with no singular figurehead, and much bickering between the various tribal chiefs.

The Hazgoratans, meanwhile, had been subject to no such indecision as by the time of the coronation of Sedrunna Ironhammer, the crown had absolute power in her lands. Although its borders did not reach as far as they do now, Hazgorata was by then a kingdom in every way, a far cry from its beginnings as an alliance of separate factions.

Seeing this as a deciding factor in the war, and with a feeling of a lack of leadership as the tribe moved ever southward, keen to get as far out of the reach of the marauding Hazgoratans as possible, many decided that a 'Chief of Chiefs' was needed.

Into this void stepped a petty Hentani leader by the name of Taruzoc. Taruzoc, already fifty-seven years of age it this time, had been headman on the village of Haruko prior to Sedrunna Ironhammer’s purge of the Hentani from their ancestral lands. He came to be one of the loudest and most persistent voices favouring the election of a new leader to bring a clear direction to the Hentani’s future.

The reason he backed this so publicly was simple - he’d spent the entire campaign up to that point making positive political connections with other tribal leaders so that they would back his calls for a vote, and when it came to it, would back his own claim to the position.

His plan could not have worked any better, and in the opening weeks of 611 AU, Taruzoc was crowned as the first Chief of all the Hentani, formally uniting them as one singlaur tribe in the process.

Published on November 10, 2019 22:00

November 4, 2019

Waungrugg and Heola

The story of Waungrugg and Heola is an ancient myth and cautionary tale. Originally of Hingarian origin, it is retold throughout the Bennvikan world.It begins with Heola, a young warrior.

She falls in love with Waungrugg, the prince she is sworn to protect.Having gained her position through once saving Waungrugg’s life in battle, Heola has become a military officer of some acclaim, despite her youth. Yet while the handsome Prince Waungrugg treats her as a confidant, he sees her only as a servant and friend.Heola believes that it is the boyishness of her military uniform that inhibits Waungrugg’s ability to see her not just as a soldier, but as a woman with romantic feelings and physical desires.

Waungrugg’s kingdom is at war. In the final great battle, Heola finds herself in the thick of the fighting.Cutting down an enemy, Heola is aghast to see the face of the soldier morph into that of hag.‘Spare me, and I will see that you become everything that your Prince Waungrugg desires.

You will spend the rest of your days in his loving embrace,' the hag pleads.Heola hesitates, thinking how dearly she would love Waungrugg to take her in his arms, profess his love for her and make her his wife.In that moment, Heola is struck down my an arrow to the heart. Seeing this as the hag runs away, Waungrugg howls in anguish and runs over to Heola, catching her body in his arms and weeping as the light in her eyes fades.The moral of the story is that Heola considered changing herself to gain the affection of another and it cost her everything.

She falls in love with Waungrugg, the prince she is sworn to protect.Having gained her position through once saving Waungrugg’s life in battle, Heola has become a military officer of some acclaim, despite her youth. Yet while the handsome Prince Waungrugg treats her as a confidant, he sees her only as a servant and friend.Heola believes that it is the boyishness of her military uniform that inhibits Waungrugg’s ability to see her not just as a soldier, but as a woman with romantic feelings and physical desires.

Waungrugg’s kingdom is at war. In the final great battle, Heola finds herself in the thick of the fighting.Cutting down an enemy, Heola is aghast to see the face of the soldier morph into that of hag.‘Spare me, and I will see that you become everything that your Prince Waungrugg desires.

You will spend the rest of your days in his loving embrace,' the hag pleads.Heola hesitates, thinking how dearly she would love Waungrugg to take her in his arms, profess his love for her and make her his wife.In that moment, Heola is struck down my an arrow to the heart. Seeing this as the hag runs away, Waungrugg howls in anguish and runs over to Heola, catching her body in his arms and weeping as the light in her eyes fades.The moral of the story is that Heola considered changing herself to gain the affection of another and it cost her everything.

Published on November 04, 2019 12:08

October 28, 2019

Author Interview - Harry Sidebottom

Hello all!

I hope you had a great weekend. I excited and honoured to say that today's author interview is with Harry Sidebottom, one of the world's most popular historical fiction authors. If you haven't read his 'Warrior of Rome' series, you really should. It's exhillerating stuff. I can't wait to start reading his new novel, The Lost Ten, which is released in paperback on October 30th. So, without any further delay, let's meet the man himself.

PB: Hi Harry! Welcome to pjbermanbooks.com. Tell us a bit about your background.

HS: Hello. My background is academic. I have taught Classical history at the Universities of Liverpool, Reading, Warwick, and Royal Holloway, London. Now I am Lecturer in Ancient History at Lincoln College, Oxford.

PB: What made you decide to become an author?

HS: It was not a conscious decision. I have written fiction since I was a child, in lots of different genres. When my first novel, Fire in the East, was published in 2008, I destroyed every previous bit of fiction. For the very good reason that the early stuff was not very good.

PB: When did you first start writing?

HS: Probably about aged four!

PB: What was the first story that you can remember writing?

HS: I remember writing a spy novel set in Berlin, when I must have been about twelve. Odd choice, as I knew nothing about espionage, and had never been to Berlin.

PB: When you begin writing a new novel, do you always know the ending?

HS: Very much so. I always plot out the first few chapters and the last couple very carefully. Where it goes in between just kind of happens. Which often means I have to go back and rewrite the beginning, and sometimes the end.

PB: Tell us about your latest novel, The Lost Ten.

HS: The Lost Ten is a novel that I have wanted to write for many years, since I first read in Procopius of the Castle of Silence, a remote Persian prison-fortress. Once a man was condemned there to mention his name carried the death sentence. The Lost Ten is my homage to the classic adventure novels, like The Guns of Navarone, that I read as a child.

PB: If you could meet one of your own characters, who would you meet, and what would you say to them?

HS: That would have to be Ballista, the hero of my seven Warrior of Rome novels. Just to say sorry for all the things that I have put him through.

PB: I’ve just had the pleasure of reading Fire in the East, the first novel in the Warrior of Rome series. Where did the idea for that series come from?

HS: I was researching a big history book called Fields of Mars: A Cultural History of Greek and Roman Battle, working on the chapter on siege warfare, when I came across a photo of a skeleton in a siege tunnel at Dura-Europos. That gave me the idea for Fire in the East, and straight away I knew I would write many more novels featuring Ballista. One day I will return and finish Fields of Mars, although the chapter on sieges, much rewritten, appeared in The Encyclopedia of Ancient Battles (2017), which I edited with Michael Whitby.

PB: What is your preferred method of research?

HS: I am obsessive about research. Usually I take six months researching a book, and about five actually writing. Apart from working in a university library, I try to visit every location.

PB: Of all your achievements, which are you most proud of?

HS: Probably renovating the farmhouse in which I grew up.

PB: What is your favourite book series to read and why?

HS: That has to be Patrick O`Brian`s Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin series. O`Brian created a complete world, both externals and mentalities, and transcended the genre of historical fiction.

PB: What are your long term ambitions career-wise?

HS: Ambition comes in different forms. I want to write a literary novel that covers the whole of the twentieth century. At a more mundane level, four of my novels have gone Sunday Times top five, but the top spot has eluded me.

PB: If you weren’t an author, what career would you be in?

HS: When I was young I had four ambitions: to be an Oxford Don, a published novelist, a professional actor, and a top class rugby player. I managed the first two, but it is a bit late for the others.

PB: What’s the next target for you?

HS: I am just finishing a proposal for a non-fiction book on Rome. The success of Mary Beard shows that there is an appetite for well-written and well-researched books on Roman history. Then it will be time to copy-edit the novel that will be published next year. In The Return a veteran of the sack of Corinth goes back to his small community in Calabria, and the mutilated corpses start appearing on the hillsides. Think historical fiction meets Scandi-noir!

PB: Tell us a random fact about yourself.

HS: I am very scared of heights. Just writing a scene with a rooftop chase makes me sweat.

Don's forget, The Lost Ten is out in paperback on October 30th. You can also find out more about Harry and his work via the pages listed below:

Official Website

Amazon

Goodreads

Official Facebook Author Page

Than you again to Harry Sidebottom for talking to us today!

Until next time, all the best!

Peter

I hope you had a great weekend. I excited and honoured to say that today's author interview is with Harry Sidebottom, one of the world's most popular historical fiction authors. If you haven't read his 'Warrior of Rome' series, you really should. It's exhillerating stuff. I can't wait to start reading his new novel, The Lost Ten, which is released in paperback on October 30th. So, without any further delay, let's meet the man himself.

PB: Hi Harry! Welcome to pjbermanbooks.com. Tell us a bit about your background.

HS: Hello. My background is academic. I have taught Classical history at the Universities of Liverpool, Reading, Warwick, and Royal Holloway, London. Now I am Lecturer in Ancient History at Lincoln College, Oxford.

PB: What made you decide to become an author?

HS: It was not a conscious decision. I have written fiction since I was a child, in lots of different genres. When my first novel, Fire in the East, was published in 2008, I destroyed every previous bit of fiction. For the very good reason that the early stuff was not very good.

PB: When did you first start writing?

HS: Probably about aged four!

PB: What was the first story that you can remember writing?

HS: I remember writing a spy novel set in Berlin, when I must have been about twelve. Odd choice, as I knew nothing about espionage, and had never been to Berlin.

PB: When you begin writing a new novel, do you always know the ending?

HS: Very much so. I always plot out the first few chapters and the last couple very carefully. Where it goes in between just kind of happens. Which often means I have to go back and rewrite the beginning, and sometimes the end.

PB: Tell us about your latest novel, The Lost Ten.

HS: The Lost Ten is a novel that I have wanted to write for many years, since I first read in Procopius of the Castle of Silence, a remote Persian prison-fortress. Once a man was condemned there to mention his name carried the death sentence. The Lost Ten is my homage to the classic adventure novels, like The Guns of Navarone, that I read as a child.

PB: If you could meet one of your own characters, who would you meet, and what would you say to them?

HS: That would have to be Ballista, the hero of my seven Warrior of Rome novels. Just to say sorry for all the things that I have put him through.

PB: I’ve just had the pleasure of reading Fire in the East, the first novel in the Warrior of Rome series. Where did the idea for that series come from?

HS: I was researching a big history book called Fields of Mars: A Cultural History of Greek and Roman Battle, working on the chapter on siege warfare, when I came across a photo of a skeleton in a siege tunnel at Dura-Europos. That gave me the idea for Fire in the East, and straight away I knew I would write many more novels featuring Ballista. One day I will return and finish Fields of Mars, although the chapter on sieges, much rewritten, appeared in The Encyclopedia of Ancient Battles (2017), which I edited with Michael Whitby.

PB: What is your preferred method of research?

HS: I am obsessive about research. Usually I take six months researching a book, and about five actually writing. Apart from working in a university library, I try to visit every location.

PB: Of all your achievements, which are you most proud of?

HS: Probably renovating the farmhouse in which I grew up.

PB: What is your favourite book series to read and why?

HS: That has to be Patrick O`Brian`s Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin series. O`Brian created a complete world, both externals and mentalities, and transcended the genre of historical fiction.

PB: What are your long term ambitions career-wise?

HS: Ambition comes in different forms. I want to write a literary novel that covers the whole of the twentieth century. At a more mundane level, four of my novels have gone Sunday Times top five, but the top spot has eluded me.

PB: If you weren’t an author, what career would you be in?

HS: When I was young I had four ambitions: to be an Oxford Don, a published novelist, a professional actor, and a top class rugby player. I managed the first two, but it is a bit late for the others.

PB: What’s the next target for you?

HS: I am just finishing a proposal for a non-fiction book on Rome. The success of Mary Beard shows that there is an appetite for well-written and well-researched books on Roman history. Then it will be time to copy-edit the novel that will be published next year. In The Return a veteran of the sack of Corinth goes back to his small community in Calabria, and the mutilated corpses start appearing on the hillsides. Think historical fiction meets Scandi-noir!

PB: Tell us a random fact about yourself.

HS: I am very scared of heights. Just writing a scene with a rooftop chase makes me sweat.

Don's forget, The Lost Ten is out in paperback on October 30th. You can also find out more about Harry and his work via the pages listed below:

Official Website

Amazon

Goodreads

Official Facebook Author Page

Than you again to Harry Sidebottom for talking to us today!

Until next time, all the best!

Peter

Published on October 28, 2019 13:15

October 27, 2019

Estarron

Estarron is the deity worshiped by followers of the monotheist Estarronic faith, the official religion of the Verusantian Empire. The faith is notorious for its teachings that all other faiths are false and should not be tolerated.

Traditional Image

Estarron is usually depicted as a male humanoid with many snakes sprouting from the crown of his head. In many images he has a disconnected, crazed expression and is holding his arms wide.

Personality

Estarron features in many myths, and not only in the Estarronic faith, as he also features in some polytheist stories too. In each of these he is shown is an incredibly powerful god, but where in Verusantium he is portrayed as a heroic, commanding protector of his followers, in other faiths he is shown as jealous, hubris-ridden and vengeful.

Rituals

There are many rituals that surround the Estarronic faith, including the cleansing of converts and the violently bloody luck ceremony.

However, the most famous is the ‘Washing’ ritual. This involves human sacrifice, where once a year, each village chooses a member of their community to be sacrificed to Estarron.

It is considered an honour to be chosen. Before the ritual, every member of the village in turn bathes in a large vat of water, washing away their sins. The victim is then doused in this water, before being tied down and having their throat slit. Their body is then burned on a pyre. It is believed that during the burning, their spirit rises to the heavens to be with Estarron, taking the entire village’s sins with them, so that Estarron himself may absolve them of their transgressions.

Traditional Image

Estarron is usually depicted as a male humanoid with many snakes sprouting from the crown of his head. In many images he has a disconnected, crazed expression and is holding his arms wide.

Personality

Estarron features in many myths, and not only in the Estarronic faith, as he also features in some polytheist stories too. In each of these he is shown is an incredibly powerful god, but where in Verusantium he is portrayed as a heroic, commanding protector of his followers, in other faiths he is shown as jealous, hubris-ridden and vengeful.

Rituals

There are many rituals that surround the Estarronic faith, including the cleansing of converts and the violently bloody luck ceremony.

However, the most famous is the ‘Washing’ ritual. This involves human sacrifice, where once a year, each village chooses a member of their community to be sacrificed to Estarron.

It is considered an honour to be chosen. Before the ritual, every member of the village in turn bathes in a large vat of water, washing away their sins. The victim is then doused in this water, before being tied down and having their throat slit. Their body is then burned on a pyre. It is believed that during the burning, their spirit rises to the heavens to be with Estarron, taking the entire village’s sins with them, so that Estarron himself may absolve them of their transgressions.

Published on October 27, 2019 23:00

October 21, 2019

The First Hentani War

The First Hentani War (1236-37 AU) was an unsuccessful attempt by the Hentani Kingdom to invade Bennvika.Prelude and Opening Stages With the bulk of the Bennvikan army in Medrodor backing the rebel Lord Varaapo against the Medrodorian King Beemu, the Hentani Chief Rokujo attempted to make a land-grab. The initial Hentani advance north into Bennvika was rapid and largely uncontested. Rokujo burnt many towns as well as the city of Zikaena before reaching the provincial capital, Ganust. With a vastly outnumbered garrison and no hope of calling a relief force, the city fell without a fight. The story goes that Rokujo tricked the city governor into ordering a military evacuation of the city. Before the column of soldiers and the baggage train carrying their families had retreated five miles from the city, they disappeared and were never seen alive again. Only much later was the ambush site discovered, along with the decaying corpses of those travelling in the convoy. Rokujo then occupied Ganust and made it his power base.The Advance on Celrun Rokujo’s strategy faltered when he attempted to besiege the city of Celrun. Unlike Ganust, Celrun had received enough warning of the Hentani advance. Another city, Tordvick, had fallen to Rokujo, but had been able to stall them with nine days of fighting before succumbing to their more numerous assailants. All of this bought time for their messengers, who had ridden out of the city soon after the advancing enemy was sighted, to reach the city of Celrun. The Bennvikan city of Attatan delayed the Hentani advance further by taking seven days to fall to the invaders. On receiving the messengers from Tordvick, the City Governor of Celrun sent word to Medrodor, telling the Bennvikan King Ansdren of the Hentani advance.The Turning of the Tide Over in Medrodor, Bennvikan-supported rebel army had gained the upper hand in the civil war that was still dragging on in that kingdom, and were virtually at the gates of the capital, Jalinna, when Ansdren received the bad tidings from Celrun. He ordered ten thousand troops to march back to Bennvika to meet the threat under Lord Bistrek Rintta. Lord Darsat Haganwold and Lord Keika Tanskeld had both volunteered to lead the force, but the king denied them, saying that as both their provinces had been attacked by the Hentani, their emotions might lead them into rash action. The Medrodorian Lord Varaapo was outraged at the lightening of his ally's force, but there was little he could do to stop it. With the approach of a Bennvikan relief force, Rokujo broke the Siege of Celrun and headed north to meet the Bennvikans in open ground.The Battle of Kestren 1236 AU On hearing of the Hentani advance, the Bennvikan general, Lord Bistrek Rintta, took up position on the plain of Kestren in southern Hazgorata, an unusually flat expance of land by Bennvikan standards. He knew that his flanks would be vulnerable, but so would those of the enemy, and the open fields meant that there would be no possibly of either side hiding units of troops from the other. Rintta arranged his force with the heavy infantry of the divisios in the middle, protected by spearman on the flanks, with his archers behind. He placed his divisio heavy cavalry on the right flank and the lighter cavalry militia on the left. Seeing that the Hentani were arranged similarly, with their foot warriors in the middle and their cavalry in the wings with their archers behind, Rintta immediately called this cavalry officers to him. When they returned to their units, they put his plan into action. Seeing the divisio cavalry abandon their position, the Hentani cavalry on the left flank charged forward, aiming to get around the side of the spearman and hit their flank. However, their charge faltered under heavy arrow fire. As the cavalry on the left retreated, the Hentani horses on the right, if one were to view the battlefield from the Bennvikan perspective, advanced without the intervantion of any arrow fire, as all was focused on those on the left, but the Bennvikan cavalry met them with terrible fury, and routed them, chasing them away. The Hentani infantry advanced, still heavily outnumbering the Bennvikans. There was heavy fighting, with both sides struggling to gain ground. When the returning Bennvikan cavalry was sited, the Hentani withdrew and mounted a fighting retreat until the Bennvikans broke off the chase. However, the day was still light, and General Rintta, who feared that another Hentani force may have been in the field advancing to reinforce the retreating warriors, was widely criticised for not pursuing them further that very day. After the defeat, Rokujo retreated back to Ganust with the remains of his army.Battle of Astabol Hill 1237 With Rokujo’s Hentani horde wintering in Ganust and Bistrek Rintta doing likewise in Celrun, hostilities were resumed in the spring of 1237 when Rintta got word of a final victory in Medrodor. King Ansdren and Lord Varaapo had decisively beaten King Beemu at the Siege of Jalinna in a deadlock that had lasted well beyond the usual fighting season. Varaapo had been crowned King of Medrodor the following January, and with the country at peace again King Ansdren was too canny to outstay his welcome and signalled to Rintta his intention to come home to Bennvika. Rintta, of course, was keen to complete his mission and expel the Hentani from Bennvika before his king arrived back in the country. Marching south with all haste to take the fight to the enemy, Rintta’s plan was to win the element of surprise. It didn’t work. Hentani scouts are legendary for a reason, and Rokujo was alerted to Rintta’s advance before the Bennvikan army had travelled twenty miles. The Hentani army therefore had the opportunity to choose the ground, and their choice was Astabol Hill, near the village of Haagromag. Placing his army at the top of the hill, Rokujo ordered his infantry to take up position at the centre of the battle line, crating a shield wall, with the cavalry protecting the flanks and the infantry behind. Contemporary sources describe Bistrek Rintta as having been incandescent with rage that despite his plan, the enemy had stolen the advantage. However, numerically the numbers were evenly matched, and Rintta’s famously disciplined and highly trained divisiomen made up half of his 10,000 strong force. As one would expect, given their position at the top of the hill, Rokujo’s strategy was a defensive one, but this was not an approach his warriors were accustomed to, and this would prove to be his undoing. After withstanding a hail of arrow fire from the Bennvikans, the Hentani shield wall was battered by repeated hit-and-run attacks by the Bennvikan cavalry. Nevertheless, the tribesmen held firm, comfortable in the knowledge that their flanks were protected by their own horsemen. That was until the entire Bennvikan army turned around, following Rintta’s order to retire one hundred paces. Perceiving this as a full retreat, Ajujo, the Hentani warrior in command of the cavalry on the left wing, led his men in a full attack without waiting for any orders from Rokujo. Seeing Ajujo’s men go forward in pursuit of the Bennvikans, the Hentani cavalry on the right flank also abandoned the high ground, charging headlong after their opponents. Rokujo’s consternation at this development is described in detail in the Hentani historian Dorezna’s (1325-1391 AU) famous ‘Chronicle of the Glorious’. Conversely, for his actions at Astabol Hill, Ajujo is described in more detail in Dorezna’s equally favoured ‘Chronicle of the Inglorious’. Ajujo’s indiscipline cost the Hentani dear. As soon as the Hentani cavalry reached the foot of the hill, the Bennvikan army turned and fought, presenting a wall of shields bristling with spears. As their momentum carried them headlong into the shields, Hentani warriors and horses were skewered and cut down. As the attack faltered, the Bennvikan cavalry swooped in from both flanks, hitting the Hentani horsemen and enveloping them. Unwilling to simply stand there and watch their comrades being cut down in a mass slaughter, the indisciplined Hentani foot soldiers charged down the hill in a spontaneous last-ditch attack, but the momentum was with the Bennvikans now and with all order in the Hentani ranks gone, the foot soldiers were easily cut down and routed. Rokujo and Ajujo were lucky to get away with their lives, heading straight for safety within their own borders and suing for peace soon after. Unwilling to commit more of the royal treasury to his soldiers’ wages, King Ansdren accepted, although not before fourteen northern Hentani towns had been ceded to Bennvika - one for every month of Rokujo’s incursion. And so, Rokujo’s attempted land-grab became a land-loss. Ajujo was widely blamed for the defeat. For his failure, he was publicly executed in the Hentani capital, Jianoko. He was hung upside down from a tree by his anckles, and archers peppered his body with arrows in an execution now known as the ‘Hanging Pincushion’. Ajujo’s name has since became a Hentani byword for a weak link in the chain.

Published on October 21, 2019 06:55

October 14, 2019

The Divisios

The Divisios are the units of elite soldiers the the Bennvikan military is famous for. While not having a large scale standing army like its neighbour Medrodor, Bennvika does have this force available at all times to defend against a sudden attack and to keep order. In this way, they are similar to the Lance Guardsmen of the Verusantian Empire.

Role and Unit Size:

Kriganheim Divisio are twice the size of others. Every province has them. Divisio One is always a cavalry unit.

Rank Structure and Uniforms:

Each Bennvikan province has ten Divisios at its disposal, numbering a total of five thousand troops the case of each province. The exception to this rule is Kriganheim where, being the capital province, each divisio is double the size of their equivalents elsewhere.

Each province has a chief invicturion, who is in charge of all ten of the province’s divisions. Each individual divisio is led by an invicturion, and the chief invicturion is simultaneously invicturion of Divisio One. Each invicturion has a subordinate officer, a corpralis, to help them run the divisio. The corpralis of Divisio One is the second highest ranking by officer in the province.

After the chief invicturion, the Divisio One Corpralis, the other invicturions and the other corpralises come the standard bearers and finally, the divisiomen, who make up the rank and file of any divisio unit. The different ranks are identifiable through the following factors:

Chief Invicturion – Single large white transverse horsehair crest with black stripes

Invicturion – Single small metal crest running front to back. The invicturion also wears a white sash across their chest.

Corpralis – Single small metal crest running front to back

Standard-bearers and Divisiomen – No crest

Armour and Weapons:

In each province, Divisio One is a heavy cavalry unit, while Divisios Two to Ten perform a heavy infantry role.

In either case, the each soldier wears scaled armour over a layer of chain mail and an emerald green tunic. Their capes are the same colour.

For defence, each soldier carries a large shield. These are rectangular in the case of the infantry and rounded for the cavalry, although cavalrymen have been known to ride with infantry shield strapped to their backs in case they have to dismount.

The Divisioman is also well armed offensively. Their first line of attack is the pilum, similar to a javelin, which a soldier would throw in unison with their comrades to interrupt the charge of an onrushing enemy. If the pilum fails to kill their victim outright and instead hits their shield, its weight renders the enemy soldier’s shield too unwieldy to use.

The Divisioman’s short sword is their primary weapon. It is designed to be used in a stabbing motion, rather than as a slashing weapon. This gives the Divisioman a significant advantage in close combat against opponents with larger swords, such as the scimitars favoured by the Hentani, the longswords of the Defroni.

The Divisioman is also equipped with a throwing axe and a dagger as tertiary weapons.

Role and Unit Size:

Kriganheim Divisio are twice the size of others. Every province has them. Divisio One is always a cavalry unit.

Rank Structure and Uniforms:

Each Bennvikan province has ten Divisios at its disposal, numbering a total of five thousand troops the case of each province. The exception to this rule is Kriganheim where, being the capital province, each divisio is double the size of their equivalents elsewhere.

Each province has a chief invicturion, who is in charge of all ten of the province’s divisions. Each individual divisio is led by an invicturion, and the chief invicturion is simultaneously invicturion of Divisio One. Each invicturion has a subordinate officer, a corpralis, to help them run the divisio. The corpralis of Divisio One is the second highest ranking by officer in the province.

After the chief invicturion, the Divisio One Corpralis, the other invicturions and the other corpralises come the standard bearers and finally, the divisiomen, who make up the rank and file of any divisio unit. The different ranks are identifiable through the following factors:

Chief Invicturion – Single large white transverse horsehair crest with black stripes

Invicturion – Single small metal crest running front to back. The invicturion also wears a white sash across their chest.

Corpralis – Single small metal crest running front to back

Standard-bearers and Divisiomen – No crest

Armour and Weapons:

In each province, Divisio One is a heavy cavalry unit, while Divisios Two to Ten perform a heavy infantry role.

In either case, the each soldier wears scaled armour over a layer of chain mail and an emerald green tunic. Their capes are the same colour.

For defence, each soldier carries a large shield. These are rectangular in the case of the infantry and rounded for the cavalry, although cavalrymen have been known to ride with infantry shield strapped to their backs in case they have to dismount.

The Divisioman is also well armed offensively. Their first line of attack is the pilum, similar to a javelin, which a soldier would throw in unison with their comrades to interrupt the charge of an onrushing enemy. If the pilum fails to kill their victim outright and instead hits their shield, its weight renders the enemy soldier’s shield too unwieldy to use.

The Divisioman’s short sword is their primary weapon. It is designed to be used in a stabbing motion, rather than as a slashing weapon. This gives the Divisioman a significant advantage in close combat against opponents with larger swords, such as the scimitars favoured by the Hentani, the longswords of the Defroni.

The Divisioman is also equipped with a throwing axe and a dagger as tertiary weapons.

Published on October 14, 2019 12:26

October 6, 2019

The Noble Wars

The Noble Wars were a triumvirate of conflicts fought over the course of Bennvika’s tumultuous eighth century AU (After Unification).

The First Noble War (708-710 AU):

By 708 AU the erratic behaviour of the Bennvikan King Crasberht, of the House of Erodren, was becoming out of control. His free spending on his own decadent lifestyle paired with a disastrous war with Etrovansia that ended in a humiliating defeat threatened to bankrupt the kingdom.

In a bid to avoid this, Crasberht gave orders to the Divisios of Kriganheim to travel around the land, forcing all of Bennvika’s richest landowners to change their will so that their entire estate would fall under the ownership of the crown upon their death. Crasberht made it clear to his soldiers that after each wealthy citizen signed such a will, it should be ensured that their death swiftly followed.

While King Crasberht’s plan was put into action in some areas in the north of the country, many of the nobles were quick to react. Lord Bamrhun Haganwold, Governor of the Bennvikan province of Hertasala, and an ancestor of the famous Lektik Haganwold, was tipped off about the king’s plan and immediately set about raising an army in rebellion, sending out messengers in a call-to-arms to every noble who yet lived.

By the time their combined military might had coalesced into one force and begun its march on Kriganheim, the rebels numbered over thirty thousand, with many of the soldiers of the deceased noblemen defecting to join the rebel cause.

Meanwhile, King Crasberht’s own actions made it difficult for him to gain allies, and when he arrogantly rode out to meet the rebels, instead of holding station in Kriganheim, he had little more than the five thousand of the Kriganheim Divisiomen (those who weren’t in other provinces slaughtering the nobility) and a handful of militia.

Haganwold and his rebels crushed the royal army in under two hours, making the Battle of Moenzorn one of the swiftest victories ever achieved in Bennvika. Some say the Crasberht fell in the battle, while others say he was taken prisoner and took his own life while in custody.

What is known for sure is that his corpse was hung from the Kriganheim city gates, where the it was picked clean by the crows.

Haganwold was quick to capitalise on his victory, and was only too happy to claim the credit for starting the rebellion that rid the kingdom of the tyrant Crasberht.

Moving quickly, he gave his backing to the childless Crasberht’s nine-year-old nephew Uthbrecht, son of the late King’s sister, Selswyth, crowning him King Uthbrecht I. The fact that Selswyth’s husband, Lord Padvold, still lived was quickly dealt with. Padvold, who had initially been named as lord protector to the young king, was soon found dead, drowned as he took his mud bath.

Within a month of Uthbrecht being proclaimed king, Bamrhun Haganwold had married the newly widowed Selswyth and been named as lord protector to the King.

Five years later, with Uthbrecht now fourteen, Bamrhun plotted to have the boy murdered, at which point the throne would pass to the king’s half-brother Rovsa, the product of the ill-fated union of Bamrhun and Selswyth.

However, the plot was exposed when Uthbrecht’s bodyguard fought off the assassin, who denounced Haganwold under torture.

Haganwold was arrested, tried and publicly beheaded for his plot. However, keen to learn from his father’s mistakes in mistreating the nobility, Uthbrecht did not strip the Haganwolds of their governorship of Hazgorata. The post of lord protector, meanwhile, went to the king’s mother, Selswyth.

The Second Noble War (749-759 AU):

The Bennvikan monarchy never fully recovered from the events of the first noble war. Yet as the memories of it became more faded, the decadence of the court began to return. Life for the poor became ever more difficult, and as the lessons of over thirty years earlier were forgotten by the wealthy, a thirst for revolution burned in the hearts of the starving common people. This passion spilt over in 749 AU.

A month earlier King Uthbrecht I had been taken by a fever, and the crown had passed to his son, the new King Uthbrecht II. The coronation, organised by the younger Uthbrecht's brother, Fiorian, was a farce. Up to a hundred thousand onlookers had been expected but, drawn in by promises of free sustenance, as many as ten times that number had begun to flow into Kriganheim. Fearful of the ferocity of the massing crowds as they begged for food, market sellers began to throw bread, fruit and meat into the crowd in a bid to keep them at bay, but this only added to the chaos. As people pushed to reach the food, some fell and were trampled, crushed to death by the crowd.

Upon hearing of the chaos and interpreting the tragic disturbance as a rebellious riot, the newly crowned king ordered the Kriganheim Divisios to restore order by any means necessary. The streets ran with blood.

This was all it took. As word of the slaughter spread to every corner of the kingdom, uprisings sprung up everywhere.

Unlike the situation surrounding the first noble war, in the second, the crown and the nobility were united, save for once significant landowner, Yarowyn Fastrydd, the Governor of Hazgorata. As the only noble in the land with enough money to pay for an army large enough to take on the might of the crown and the other governors combined, he saw the opportunity in this.

He sent out messengers to all the major towns across the land, telling the local people that he would reward them greatly if they were to join the uprising. As Yarowyn predicted, given that he was very open about his opposition to the crown, King Uthbrecht marked him as they greatest threat, and marched on the Fastrydd stronghold at Chathran. Yet this move against Yarowyn left much of the kingdom woefully undermanned from the perspective of the royal army, especially as, once they had Yarowyn pinned down as they besieged him at Chathran, they found themselves unable to force a breakthrough, Uthbrecht was forced to retreat in 751, leaving a small force under Fiorian to keep his sword in Yarowyn's back and prevent him from moving.

The reason for this was a marked change in circumstances in the east. Where until this point the pockets of resistance outside of Hazgorata had been swept aside by the various royal provincial armies loyal to the king, in the marshlands of southern Asrantica, Bennvika's easternmost province, a large force of approaching ten thousand commoners had gathered under the inspirational leadership of one of their own, and had smashed the provincial army sent to crush them.

This charismatic leader was the now legendary Zatra. A horse breeder by trade, she had inspired her local townspeople by leading them on horseback against the local garrison. These may have only been less than ten royalist troops, but the image of a local woman riding a horse and charging at the king's soldiers stirred the hearts of all who saw it, and many who only heard of it. Having taken control of the town, Zatra used her contacts and local influence to equip more of her gathering group of supporters with horses. They may not have been skilled horsemen, but for the first time in the conflict, there was an army in the field led by a person of no noble blood, with cavalry at their disposal.

As word of Zatra's growing army spread, her numbers stretched into the thousands. Two further provincial armies faced her and were thrown back as she marched on Kriganheim, before the king's army blocked her way at the Lavaklan river.