Vivian Asimos's Blog: Incidental Mythology, page 5

September 19, 2023

The Reality of Monsters

With the approach of October, comes the slow march of monster season - my favourite time of year. As I’ve done in the past, each blog post in October will be a review of a monster. So I thought I’d lead into the world of monsters by thinking about the reality of monsters.

By reality of monsters, I do not necessarily mean the human monsters in our world, like serial killers. No, the reality of monsters also includes the monsters we typically think of as fun narratives to tell - the vampires and werewolves are real too.

When we read about previous ages in our world, we hear about belief in monsters: in demons, and werewolves, and hideous creatures crawling through the forests. We think of this as being irrational beliefs that mark the pre-modern world. But as David Stannard wrote in 1977:

We do well to remember that the [pre-modern] world… was a rational world, in many ways more rational than our own. It is true that this was a world of witches and demons, and of a just and terrible God who made his presence known int he slightest acts of nature. But this was the given reality about which most of the decisions and actions of the age, throught ehe entire Western world, revolved.

I think often we think of the reality of monsters as being something that demonstrates they are inherently manifest somewhere physically in the world. Belief in actuality is one thing, but that is set apart from the reality of monsters. The existence of the phenomonon is not what gives the monster its strong force in the world. In fact, people still believe in monsters in the way they have in ages beforeTo see the reality of monsters is not to observe the monster, but rather to observe the people who belong to the monster. A monster is not known through its bright eyes in the dark of the night, but rather in the effect it has - its impact on society and individuals.

A monster shows us what a culture or a society finds horrifying. It shows us what they view as possible and impossible. It shows us how a culture marks out its boundaries - how categories are marked out as well as who is included in it, and who are the outsiders. A monster shows us a reflection. Through the monsters eyes, we see how a culture views itself. What is respectful and “normal”, and what is filled with scorn and disgust.

Monsters are not just figures of the past. They exist now, and while many talk about the physical existence in one dismissive way, the impact and effect their stories have demonstrates how monsters are inherently real.

Media studies scholar Patricia MacCormack writes about monstrosity, and how monsters are often seen as that which marks difference. She writes: “in the most reduced sense then, through concepts of adaptability and evolution itself, all organisms are unlike - we are all, and must be monsters because nothing is ever like another thing, nor like itself from one moment to the next”.

I think this is what I love the most about looking at contemporary monsters. It shows us the impacts of society, and more importantly it shows us ourselves. The reality of monsters is not in the footprints left behind in the mud, but in the way we treat the people around us and think about the world we move through. Its in the way we recoil at certain thoughts that seem so undefinably terrible to us, and more importantly in the way that we do not question these responses.

September 5, 2023

Some Musings on Fan Theories

Fandom is amazing. What I love about fandoms is how it gives space for unbridled creativity, and a place to love the things we love unashamedly. Through fandom, activities that are typically considered individual and isolating can become communal. Reading, for example, is no longer something you do quietly on your own, but rather something you share on TikTok or other places. You talk openly about what you’re reading, how you feel about it, and connect to others who are reading the same thing.

Part of this connectivity means that there is a heavier reliance on writing. Fans have to communicate their love through writing to connect to others. Today, I want to talk briefly about fan theories - one of the ways in which people connect to others through the things they love.

There are three types of fan theories: predictive theories, explanatory theories, and alternative theories. Predictive theories explore possible ways narratives will unfold. Predictive theories are the most temporary of the fan theory, because as the narratives continue they will be proven either right or wrong. These are not meant to be long lasting pieces, but momentary narratives and connections. Predictive theories primarily rely on the presented text. Every argument has to be rooted in the elements and pieces already presented in the narrative.

Explanatory theories are presented as ways to bridge gaps that are in the original narrative. These are for pieces that have not been fully explained, back stories for characters that have not been explored, or gaps in time in the narrative that has not been fully explored in the original. Fans use their knowledge of the text as well as personally creativity to fill in these gaps for themselves. Like Predictive theories, explanatory theories rely on what’s presented in the text, but also on what’s not presented. Where Predictive theories are looking for an outcome in the narrative, explanatory theories are more focused on the processes that arrive at an outcome.

The last type of fan theory are alternative theories, which are when fans create visions for their loved fictional worlds. In other words, these are when fan writers conceive of what could have happened if things happened differently, or it was a different genre. The previous two theories, predictive and explanatory, do not need to have as much connection to authorship in regards to the fan. In contrast, alternative theories are more heavily reliant on connections to authorship.

Regardless of the type of fan theory explored, fan theories provide an avenue through which audiences can directly interact with the stories they love. They can claim their love, and especially through a community, by writing alongside the authors of the original pieces of media. The fan theory, in many ways, provides a sense of power to the fan, but not one that overshadows the abilities of the original authors. Rather, its a way for fans to relate directly to the media through their own art and creativity.

August 22, 2023

Structuralism and Myth

In previous posts, video essays, and just general work I’ve done on pop culture and myth, my actual form of analysis has always been structuralism. So I decided to take some time here to explain a little about what structuralism is, so if you get into the other stuff you understand a little more about where I’m coming from.

Structural anthropology was founded by Claude Levi-Strauss. Levi-Strauss was inspired by linguistics, particularly the work of Ferdinand de Saussure. Sassure argued that linguistics should spend less time focused on speech acts, and more on the context the speech is happening. Saussure was the one who established a differentiation between “the signifier” (the word) and “the signified” (the thing).

There was an idea that there was an inherent connection between the word “dog” and the thing that we call a dog. In other words, there is something doggy about the word dog. Saussure, on the other hand, thought differently. He believed that the word “dog” did not necessarily relate to “dog” as a thing, but as a concept.

For anthropology, Levi-Strauss understood that the ways we think about the world is more based on concept and organisation of thought than the things themselves. The way we categorise and think about the things we interact with are not inherent in the things themselves, but are socially and culturally based. As we grow in this world, society tells us what things are and how we should think about them. We look at a dog and are told its a dog. But later we see something that’s way bigger than that original dog but it’s still a dog.

This is something taught to us, rather than something we feel inherently.

Dogs are obviously an example here, but we can apply this to more complicated conceptions. Instead of dogs, let’s think about people. We have people who are “like us” and people who are not, and this is also something which is taught. Some people are categorised in different boxes, and some humans are not categorised into the people category at all, depending on the social world you grow up in.

In Structural anthropology, we understand these social categories are embedded in a lot of what we do. If this is what our worldview is based on, then the things we produce are going to also reflect this. This means that a society’s mythology also reflects these categories, and by analysing mythology we can get a detailed view of what this categorisation looks like.

So, by analysing our popular culture, we can understand the society that made that media’s form of categorisation.

So the way we actually do this analysis is by partaking in what appears to be like an archeological excavation. The structural method starts with finding mythemes, which are the smallest units that make up a myth, inspired by the phoneme in linguistics. Mythemes are the smallest element of a myth, and one that cannot be broken down any further. Each mytheme functions based on relations. Mythemes don’t live in isolation, but are directly related to other mythemes, and through this relationship builds the foundation of the myth.

We do this by starting at the narrative level, the actual story as presented to us. This is the most contextually situated. We got all the fancy words, the fluff around the presentation, all of that.

Under that is what we call the S3 level, one step removed from the narrative. This level uses the mythemes and element of the myth while understanding their context, and we begin to categorise and understand the relations between them.

And then we get to the S2 level, which is the next step abstract. The S2 level is as deep as I typically go, even though Levi-Strauss believes there to be an S1 level which he thinks is biologically based. I disagree with this, along with a few other structuralists who have come after him, but that’s probably a whole ‘nother conversation for a whole ‘nother time.

The key elements, the mythemes we are looking for, are found in narratively significant roles and relationships, which can be found through both action and inaction. For example, silence and noise are both possible mythemes. These can often be represented in a key character, a theme, or location. Once we find a few mythemes, we can look at how they relate to one another, and see how they are categorised through their relationships with each other.

Essentially, structuralism can be seen as somewhat similar to a textual anlaysis. The narrative is relegated as a text, and analysed as one. The point of a structural study, like the one we will be doing on Stranger Things, is not to assess the text as text, but as a cultural artefact that reflects cultural categories.

And that’s the structural study of myth! I hope it wasn’t too boring, but I think it shows one of the ways that myths can be analysed. It tends to be my method, though it’s not the only one, and perhaps not even my only one. I see method as a tool, not a doctrine.

August 20, 2023

Stranger Things: a Structural Mythic Analysis

A couple months ago, I posted a video essay all on the general thesis of Incidental Mythology as well as me as an academic: our popular culture is our mythology. The video actually didn’t do too bad, so I thought I’d take a bit of time to give a little more detail and complication to the topic. So today, I want to dig into what it means to actually study pop culture as mythology, what we can learn about ourselves through pop culture, and provide a little bit of an example of a type of analysis we can do to our narratives to get at the answer to these questions. If you need a primer on the general idea of pop culture narratives as mythology, go check out my previous video which I’ll link in the description below.

But for now, let’s first talk about mythology more generally. As an anthropologist, I understand myths as cultural artefacts. Myths can tell us about people in the same way that looking at their other arts can. They are parts of a culture or a society, and as such are reflections of this. So by studying and analysing myths, we can also get into the heart of the dynamics of the people who tell these stories.

One of my preferred ways of digging into pop mythology is through structuralism. Now, when I talk about structuralism in this essay, I’m referring specifically to structural anthropology. Like many things, there are a lot of different forms of structuralism, like in linguistics and literature. That being said, structural anthropology is actually inspired by linguistics.

Structural anthropology was founded by Claude Levi-Strauss. Yes, Levi-Strauss. In fact, this Levi-Strauss was cousins with the jeans Levi-Strauss. But our Levi-Strauss was more interested in mythology and anthropology. He saw something familiar in linguistics. Ferdinand de Saussure argued that linguistics should spend less time focused on speech acts, and more on the grammar and context. Sassure was the one who established a differentation between “the signifier” (i.e. the word) and “the signified” (i.e. the thing).

There was an idea that there was an inherent connection between the word “dog” and the thing that we call a dog. In other words, there is something doggy about the word dog. Sassure, on the other hand, thought differently. He believed that the word “dog” did not necessarily relate to “dog” as a thing, but as a concept.

For anthropology, Levi-Strauss understood that the ways we think about the world is more based on concept and organisation of thought than the things themselves. The way we categorise and think about the things we interact with are not inherent in the things themselves, but are socially and culturally based. As we grow in this world, society tells us what things are and how we should think about them. We look at a dog and are told its a dog. But later we see something that’s way bigger than that original dog but it’s still a dog. This is something taught to us, rather than something we feel inherently.

Dogs are obviously an example here, but we can apply this to more complicated conceptions. Instead of dogs, let’s think about people. We have people who are “like us” and people who are not, and this is also something which is taught. Some people are categorised in different boxes, and some humans are not categorised into the people category at all, depending on the social world you grow up in.

An important aspect of this is that the way one culture or society categorises the things they meet is not the same as another. This can result in a lot of miscommunication or issues between people. Because sometimes we take for granted that these are learned categories, rather than inherent categories. There is nothing inherently doggy about the word dog, it’s just a word. There is nothing inherently “like me” that someone else is, but rather aspects which are socially learned and labelled.

In Structural anthropology, we understand these social categories are embedded in a lot of what we do. If this is what our worldview is based on, then the things we produce are going to also reflect this. This means that a society’s mythology also reflects these categories, and by analysing mythology we can get a detailed view of what this categorisation looks like.

So, by analysing our popular culture, we can understand the society that made that media’s form of categorisation.

Alright, now that’s all detailed out of the way, let’s talk about how we actually go about doing that. In this video, I’m going to explain how it all works, but in the next one I’m going to give an actual structural analysis of a piece of pop culture: the first season of Stranger Things. But for now, I want to explain a little about how the actual analysis works.

The structural method starts with finding mythemes, which are the smallest units that make up a myth, inspired by the phoneme in linguistics. Mythemes are the smallest element of a myth, and one that cannot be broken down any further. Each mytheme functions based on relations. Mythemes don’t live in isolation, but are directly related to other mythemes, and through this relationship builds the foundation of the myth.

The structural method is basically like an archeological excavation, but one through a myth. We start at the uppermost level, the narrative level, which is the most surface level and the most culturally and contextually specific. This is the story itself, the written, or spoken word, that we are given.

Under that is what we call the S3 level, one step removed from the narrative. This level uses the mythemes and element of the myth while understanding their context, and we begin to cateogrise and understand the relations between them.

And then we get to the S2 level, which is the next step abstract. The S2 level is as deep as I typically go, even though Levi-Strauss believes there to be an S1 level which he thinks is biologically based. I disagree with this, along with a few other structuralists who have come after him, but that’s probably a whole nother conversation for a whole nother time.

The key elements, the mythemes we are looking for, are found in narratively significant roles and relationships, which can be found through both action and inaction. For example, silence and noise are both possible mythemes. These can often be represented in a key character, a theme, or location. Once we find a few mythemes, we can look at how they relate to one another, and see how they are categorised through their relationships with each other.

Essentially, structuralism can be seen as somewhat similar to a textual anlaysis. The narrative is relegated as a text, and analysed as one. The point of a structural study, like the one we will be doing on Stranger Things, is not to assess the text as text, but as a cultural artefact that reflects cultural cateogires.

One last thing on the structural study, Levi-Strauss’s S1 level, and his understanding of the biology of myth, shows that he truly thought of structure as somehow biologically derived. However, social scientists have since shifted to see a difference between biology and society. This is pretty much the nature/nurture argument but in the social sciences.

Essentially, Levi-Strauss did not really give enough space for storytellers, and actors in society, to have any kind of agency. Structure was something that just happened to them. However, we can look at societies over time and see how ideas, worldviews, and social ideals can change over time. This means that a society’s structure can change - we are not the same as we were several hundred years ago, at least I would hope.

And because of that, I follow the way of neo-structuralists like Seth Kunin and Jonathan Miles-Watson, who have moved beyond this biologically derived aspect to one which is more socially based. This means that there is also more focus given to social agency. I want to give space to the community who tells stories - the writers, the actors, the audience - they each have their own relationship to the text and their own meaning within it. These individuals have an agency over the way their story is being told, shared and related to.

Alright, now that the boring explanation stuff is out of the way, let’s show you what this actually looks like through the first season of Stranger Things. We’re focusing on the first season because otherwise this would be a whole book instead of an essay.

The first season of Stranger Things is focused around the disappearance of Will Byers, a child from the town of Hawkins. While Sheriff Hopper, Will’s friends known as “the Party” and his mother and brother hunt for him, the true culprit is a figure from an alternate universe called the Demogorgon, accidentally brought to the town of Hawkins by a local government facility. Here, we can dig into a few major mythemes, including characters, figures and locations.

Let’s start with locations. While there are a variety of different set pieces we see through the season, including two of the kids’ houses (Mike’s and Will’s), their school, and the government facility, most of the settings can be considered either Hawkins, the village, or the Upside Down, the name of the alternate universe. Two of the locations are associated with both the village and the Upside Down. Mirkwood, the forest near Hawkins close to where Will lives, and the government laboratory are both locations in some way associated with both the Upside Down and the village itself.

Mirkwood is associated with both the Upside Down and Hawkins because it’s the location Will disappears, and where Mike’s sister Nancy crawls into the Upside Down. Similarly, the government lab is where there are rifts, and the ability to create more rifts, between the world of Hawkins and the world of the Upside Down. While there are forms of Will’s house in the Upside Down, it’s not a location in which the transition is possible in quite the same way that it is with Mirkwood and the lab.

Mirkwood is an interesting location to consider in the show. The forest is a common symbol and location found in folklore, legends, and myths. In Germanic folklore, as recorded by the Brothers Grimm, the forest was seen as a transformational place, a location in which society’s conventions cannot hold. Mirkwood is similar here. It’s a location in which people are transformed and moved to new categories and revealed to hold new relations. It’s where Will goes missing, but it’s also where Nancy has a realisation about Will’s brother Jonathan and begins to see him in a more positive light. Even though Barbara, the other victim of the Demogorgon, gets taken while at someone’s house, the house backs against the forest, and it’s from this forest the monster comes.

The laboratory, while not a traditional forest, has a similar functioning to the forest. It’s a transitory place, a location in which there are transformations in worldview as well as transformations in world. It’s the location for physical shifting, between Hawkins and the Upside Down, and where Sheriff Hopper first gets a glimpse of the possibilities of the Upside Down, transforming his perspective.

The locations in the season are interacted with by the characters, and each character has specific relationships with particular locations. One of the important groups of characters is The Party, or Will Byers’ friends Mike, Lucas, and Dustin. The show opens with the group playing Dungeons and Dragons, and the three remaining characters refer to their group dynamics and their game-character dynamics even when not playing. Will’s family, his brother Jonathan and his mother Joyce, are also characters who are actively working to find Will, at first separate from the friends. Mike’s sister, Nancy, and her friend Barb, begin as separate figures not relating to the missing boy, but become embroiled in it when Barb also goes missing. Sheriff Hopper, an alcoholic, also fights to find the boy.

The government officers, primarily that of Dr Brenner, is an ominous figure in the show and one who frequently hinders the investigation into Will’s disappearance, or actively hunts the Party. Eleven is a child found by the Party who has mysterious powers, and who is actively running from Dr Brenner. Eleven wishes to help the Party find their friend but is often conflicted about how to do it without potentially harming them or herself. Last is the figure of the Demogorgon, the monster prowling the world, taking individuals.

We can categorise these characters based on their relation to landscape. Most of them are more closely related to the town of Hawkins. They are residents of the town who happy to embody the quiet, middle-America town from the 1980s. The characters who fall into this category are the Party, Nancy, Jonathan, Joyce, and Sheriff Hopper. Initially, Barb is also in this category, though does not remain there because she gets moved to the Upside Down.

This leaves Dr Brenner, the Demogorgon, and Eleven. These characters a little more complicated. The only one that is directly associated with one of the locations we have discussed is the Demogorgon, a figure directly from the Upside Down. Even though it moves between Hawkins and the Upside Down, it’s primarily associated with the alternate universe.

Dr Brenner is a more complicated figure. While Brenner is not a monster from the Upside Down, he’s not really associated with the figures from Hawkins. Even though there are clearly issues between the characters in the Hawkins category, there is still an inherent community feel to the connections between them. They know each other and understand the connections and contexts of each of the community members, even if they don’t like each other. Brenner, on the other hand, is a clear outsider, a figure who doesn’t belong to the community. That being said, he’s still a human, not one from the Upside Down, and therefore wouldn’t be suitable to associated him directly with the Upside Down. Though the Demogorgon, and the relationship between the Upside Down and Hawkins was made due to Brenner’s interactions.

Eleven is also a figure hard to categorise. Like Brenner, she is not an actual member of the community in season one. She is an outsider to Hawkins, and from the same location as Brenner as she sees Brenner as a parental figure. However, she’s not really like Brenner either. She has compassion for those around her and harbours a great fear toward both Brenner and the world of the Upside Down.

For now, let’s put Eleven and Brenner to the side and think about the type of structure we can sketch out using our other mythemes and their relations. We have Hawkins, and all its associated characters, on one side, and the Upside Down and its related characters on the other. Two characters move actively from Hawkins to the Upside Down: Will and Barb. This means that there is a positive correlation between the two categories, as there is room for movement. By positive relation, we mean whether or not there is combination or possibility for transition, rather than the two categories viewing each other as positive. It’s more of a functional understanding rather than a value judgement.

Essentially, our structure so far could be sketched out as such:

The overlapping circles are drawn to demonstrate a positive relationship between the two groups which means there is possibility of movement.

Before we move on to thinking about the movement between these categories and how that movement occurs, we first should come back to the two figures we have yet to place. Eleven and Dr Brenner still have no place in our structure yet. The solution may be to reconsider the naming and consideration of what the categories are. Hawkins and the Upside Down served as viable categories due to demonstrating the relationships had between mythemes of locations and characters, but these locations are themselves mythemes.

We can rethink of the Hawkins vs Upside Down as the Inside vs the Outside. Hawkins is the community of the story, the central group in which there are hierarchies and prejudice, but can recognise threats from the outside world at the same time. If we reconsider the categories as simply in group vs outgroup, most of the relations stay the same with the exception of the addition of Dr Brenner to the world of the outsiders. This relegation actually makes a bit of sense, as Dr Brenner is often seen as just as monstrous and scary to the Party, and even to Sheriff Hopper, as the Demogorgon.

However, this does not resolve our issue with Eleven. Eleven is initially an outsider to the community and viewed with suspicion from several members of the Party. However, as time progresses, and Eleven demonstrates her willingness to help the community and her wanting to be part of the loving friend group she finds herself in, the community gathers around her to protect her. However, her appearance not fitting with typical styling of female children of the time, and her reluctance and difficulty in speaking, still paints her regularly as an other.

Eleven is a complicated figure because she is both of the inside and the outside at the same time. Like the Demogorgon, she has the ability to manoeuvre through and between categories, and is simultaneously fitting into both categories while not really fully belonging to either. Eleven is therefore a mediator, a figure which exists between categories, and can at times facilitate their movement between.

It is Eleven who brings the Demogorgon to Hawkins, even if the action was forced upon her by the government agency and Dr Brenner. She is also able to traverse aspects of the Upside Down in order to find Will and Barb. While she has difficulty bringing Will back, she is still able to traverse enough to find out he is still alive and where he is.

However, I would venture to add an addition to the mediating figures: the Demogorgon. I know we associated the Demogorgon with the Upside Down, and the Outside, category. However, like Eleven, the Demogorgon travels. While it is mostly associated with the Upside Down, it is also a figure which moves categories – travelling to the in-group to prey upon the individuals there. It is not just a figure which remains in the Upside Down, but one which moves, and seemingly with agency.

Levi-Strauss’s understanding of myth is tied to how myth moves from establishing an awareness of oppositions and progresses towards their resolution. For Stranger Things, we have to categorical problems to resolve: the mediatory figures of the Demogorgon and Eleven. The problem of the Demogorgon is solved with its death. The problem of Eleven is more complicated. It is evident Eleven is not fully able to settle in the worlds of the Inside/Hawkins because of her extraordinary abilities. So her separation is resolved by a feigning of death, though one that is left as potentially open at the end of the series when Sheriff Hopper is seen leaving Eleven’s favourite food of Eggos at her supposed grave site.

In order to understand what Stranger Things is saying about fear, and what to fear, we should first consider the context of Stranger Things. The show takes place in middle America in the 1980s. While the show replicates filming aspects of the era, and even draws on popular films of the time such as Jaws and E.T. However, despite drawing on the 1980s, the myth of Stranger Things is a reflection of the time period it was written and produced, around 2016. That being said, there are a lot of similarities between the United States at the time the show is set and the time it was made, which is reflected in the way the structure of the show is understood and reflected.

First, we should talk about the nature of a monster. In Jeffrey Cohen’s seven thesis of monster studies, one of the ways a monster is understood is as a “harbinger of categorical crisis”. Structuralism can demonstrate this type of monster well, as it functions on the understanding of categories and finding elements which do not fit.

Our two figures who do not fully fit into categories neatly and cleanly are Eleven and the Demogorgon, both of whom are viewed as monstrous throughout the show. Eleven is consistently viewed as monstrous from those who are more related to the government agency, including “patriotic” adults who follow the government figures’ orders regardless of what it means more solidly for the other characters involved. Eleven is a tool, a thing to be used in the same way the Demogorgon is.

On the other hand, some characters do not see Eleven as a monster, but only as a mediatory figure who is more vulnerable than terrible. Sheriff Hopper in particular views Eleven as a sympathetic figure to be protected alongside the town, rather than a figure to be despised and rejected.

Stephen Prince notes that the United States of “today” is “an extremely conservative nation” and that its attention on “right-wing policies began in the eighties” (Prince 2007, 1). The Ronald Reagan era America is being reflected in Trump’s America, as noted by Trump’s insistence on “making America great again”, a slogan used by Reagan in his 1980s presidential campaign. It is precisely this xenophobia and racism that Stranger Things seeks to alter.

When the show is beginning to get closer to hitting its climax, the town of Hawkins is not being run over by supernatural forces like Eleven, but rather the government. The government sees Eleven as a test subject, one that needs to be controlled or neutralised. Despite this, the mediatory figure of Eleven does not act as a monster for the other characters of the show, but rather as a unifying force, and one that connects others to the central aim of the show: to save a child.

The structure of Stranger Things as painted in our structure can be understood in two different ways depending on the characters in question. For the government figures and the “patriotic” adults (primarily noted by Mike’s father who calls himself a “patriot” to the government officials in his home), the maintenance of the structure should come at the destruction of those who are not “like us”. This is seen in their treatment of Eleven as a something needing controlling and neutralising. Eleven is a social Other who are not seen as vulnerable and fleeing persecution and brutality, but rather as a the monster that threatens the society she comes to.

On the other hand, there are characters who have different viewpoints. Sheriff Hopper, for example, sees Eleven as a vulnerable and marginalised figure. He sees the same for Will Byers, a child from a low income home whose disappearance does not seem to be fazing the town.

In fact, there is a level of consideration regarding homophobia as well, where those in the LGBT+ community as social others not worth of protection. When the police are questioning Joyce on her missing son, she comments he had few friends and was bullied a lot for people thinking he was “queer”. The police interject and ask “And is he?” To which Joyce responds that does not matter. He’s missing. This interaction shows the social constructions of society, and that the in-group and out-groups of Hawkins in the structure are more controlled for some in the society than for others.

This shifting is not necessarily a shifting of structure, but rather of interpretation of structure. For Sheriff Hopper and the Party, Eleven is still a transitionary figure who is both inside and outside the community at the same time. This aspect of the structure does not change from character to character, but rather the perspective on the figure who is mediatory does. While some view her as monstrous, other as vulnerable.

Anthropologist Seth Kunin demonstrates how structure can change over time, typically from a privileging of some elements of the structure of others. Some elements are emphasized and other de-emphasized depending on the needs of the individual and the goal to achieve (Kunin 2001, 2009). This means that structure is not necessarily as biologically derived as Lévi-Strauss suggested. The agency given to storytellers means that individuals or groups of individuals can work to try and change the structure of the societies they are a part of. This is what eventually leads to revolutions, or other alterations of worldview over time.

For Stranger Things, they push for the monster to not be considered as such because of it’s inability to fit into “normal” society. In fact, the great fights in the show are not between the monsters, either Eleven or the Demogorgon, and the town of Hawkins. The revolutionary figures are the primary fighters in the show: the children bullied because they are nerds and friends with “a queer”, the outcast and low-income Byers, and the alcoholic distrusted Sheriff. These are the individuals who take up arms, not against the monster, but against the government and the forces that seek to continue to persecute the vulnerable.

At the Screen Actors Guild Awards in January of 2017, Stranger Things won the award for “Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Drama Series”. Upon accepting the award, David Harbour, the actor who plays Sheriff Hopper, said the following:

“In light of all that's going on in the world today, it's difficult to celebrate the already celebrated Stranger Things. But this award from you, who take your craft seriously, and earnestly believe, like me, that great acting can change the world is a call to arms from our fellow craftsmen and women to go deeper. And through our art to battle against fear, self-centeredness, and exclusivity of our predominantly narcissistic culture, and through our craft to cultivate a more empathetic and understanding society by revealing intimate truths that serve as a forceful reminder to folks that when they feel broken and afraid and tired, they are not alone.

We are united in that we are all human beings and we are all together on this horrible, painful, joyous, exciting, and mysterious ride that is being alive. Now, as we act in the continuing narrative of Stranger Things, we 1983 Midwesterners will repel bullies. We will shelter freaks and outcasts, those who have no homes. We will get past the lies. We will hunt monsters.”

David Harbour’s speech demonstrates the resistance given to storytellers who reject the nature of some aspects of cultural structure given to them. The shifting nature of fear is not due to outside forces, but rather are formed to resist the notion of a culture telling us who to fear, when we reject such forces entirely. It is a different perspective on a structure, one which sees most transitory figures as monstrous. Instead, they privilege a different understanding, one where the vulnerable are supported, and the monsters are those who monstrasize the vulnerable. In other words, its attempting to change the cultural worldview the show is brought into, one to change the perspective on our structure, and to bring fear to those telling us to ostricise the vulnerable, and to protect those who are caught in between.

August 8, 2023

Clothing and Identity

After spending quite a lot of time with cosplay, looking at how to distinguish it, and starting the process of trying to keep myself from already looking into other potential research projects, I’ve been obviously spending a lot of time thinking about the art of dressing. A lot of studies of fashion and dressing talks about how fashion is a form of communication. As Malcolm Barnard puts it, fashion is what makes “us” into “us”. It becomes a form of identity creation and cohesion and allows people who are “us” to recognise “us”.

People have been using dress in this way for a very long time. Religious dress is often markers of in-groups and out-groups, while doubling to communicate beliefs and worldviews. This can be from the hijab to modest dress to folk costumes. We seldom wear something just to wear it. What we find comfortable and easy also says a lot about us, in the same way that subcultural styles like punk can.

When we get dressed, it is mot just the clothes we have to consider. Clothes go onto a body. It is through our bodies we see the world, and in it that we are seen by the world. Seeing me is also seeing my body and seeing my dressed body. Anthropologist Mary Douglas wrote about how we all have two bodies: a phsycial one and a social one. The social body in many ways controls the way our physical bodies are read and understood by the people around us. Our physical experiences and understanding of our physical body is always 'clothed' by our social categories and social worlds. In many ways, there is no such thing as a nude body, because we are always clothed in these thoughts and considerations. Douglas's two bodies are always in interaction and communication with each other, constantly reinforcing the categories of one on to the other. Essentially, our bodies are more than biological mechanisms. They are also social tools for communication and categorisation. For example, my gender is inscribed as both a social body and a physical body, and which gender I am is read through the social as a way of thinking they understand the physical.

Dressing and fashion is always located in the world in a physical sense. It takes up space in the world. Our bodies are always taking up space, and so do our clothes. We always orient our dressing to the places and spaces we are in and going to. When I was teaching at a university, I would dress for my classes differently than if I was going on a date with my husband.We also dress for the larger social worlds we are in. Sometimes, we dress counter to the social expectations on purpose to try and subvert the expectations put on us, but this subversion also is reliant on knowing that social expectation.

But our bodies, and our dressed bodies, are not just for the social worlds around us. Sociologist Erving Goffman points out how the body is not just a property of the social world, but also property of the individual. In fact, our bodies are the way we explain and demonstrate our identities to the people around us. Clothes provide us with the ingredients necessary to perform our identities.

Even though the social worlds around us have expectations and ways of reading our bodies, this is not done without our own impact. As I mentioned before, people can try and subvert expectations directly by purposefully dressing in a way that denies the expectation. Gender, and the way gender dynamics play on dressing and fashion, is a good example of this.

Clothes and dressing are a form of communicating ourselves to the world around us. We demonstrate our interests, our community groups, and our morals through the way we dress. There's a lot of research available on the way subcultures dress to express their identity. Punk, for example, utilised fashion to directly cause discussion in mainstream society. But subcultural style is just one example of the many ways we dress to denote our identities, morals and social connections.

July 25, 2023

Cosplay and Monstrosity

I want to return to monsters once again, today. But this time, in a slightly different way. Even though I talk about monsters as cultural artefacts, I have focused on monsters that we recognise as monsters: the Slender Man, Momo, even older monsters like the Wendigo. But monsters can also be cultural in other ways.

Monsters are understood as monsters due to the way they are situated in our cultural thought. As we grow up in our society, we are taught what is defined as what, and how its is placed in our understanding. Even though two animals can look actually quite different from each other, they’re both dogs. More complicated categories are ones like which humans are categories to be like “us” and which ones are pushed as “others”. We grow up with these categorical understandings because they are socially based - someone from a different place than us may have different categories.

As Jeffrey Cohen says, the monster is harbinger of categorical crisis. In other words, the monster is that which shows us that these categories our society has given us is not as firm and solid as we like to think. Let’s think about a classic monsters real quick: the vampire. The vampire’s monstrosity is partly due to its bridging of categories which should never cross. Things should not be both alive and dead at the same time. Things which are categories as “alive” and have the characteristics of “alive” should not ever be in the category of “dead”. And yet, the vampire is a bridge between these categories, a figure which exists in both and neither. The vampire is a monster because it demonstrates to us that these categories we have used as a foundation of our worldview and understanding are not as solid as we like to think it to be.

A cosplayer screaming during the cosplay competition at MegaCon Manchester 2022.

Monsters are not always bad. Some monsters are viewed positively, depending on the way the culture understands the categories which are being crossed and whether or not this is something which should happen. Jesus is a great example of this - someone who is considered as both divine and human at the same time, two categories which are normally not crossed. And yet, Jesus is a positive monster, one through which Christians can gain better access to the divine. For that culture or society, this particular type of monster is actually something to look for and connect with.

So with that, I want to talk about a different kind of monster: a cosplay monster. Now wait, here me out. One of the things that I find particularly interesting about cosplay is that it bridges the worlds between fiction and reality. Normally, fiction and reality are two separate categories, ones which never cross. When they do for someone, the society around them view them as in need of some kind of help. But cosplay actually does this.

During the amazing time of a convention, the fiction is alive around us. Not just because of the many plushies being sold and the excited fervour of other fans who surround us, but because of cosplayers. We see our favourite characters, get to take pictures with them, and even sometimes get to see them perform our favourite moves as they go across a stage.

Cosplayers allow us to live in the wonderful liminal space in which both categories - the category of the real and the category of the fiction - are both present at the same time. Cosplayers live in the muddy grey area between the two worlds, and show us that maybe thinking about these categories in this way may not necessarily be the right way to consider it.

So, in essence, cosplayers are a kind of monster. And through this monstrosity, cosplayers are able to change our understandings of fiction, of our own social categories, can has the potential to be subversive.

July 17, 2023

Notes on a Scandoval

So, look. I know that the cross over between people who enjoy hearing about the intricacies of videogame storytelling and people who like reality television may not be the biggest overlap, but I think I do a good enough job at not inundating this channel with just as many topics on reality television as I have on video games, scripted shows and movies. Besides Kim Kardashian, I haven’t any time here at all. But you know I couldn’t’ let one of the biggest scandals of reality television to pass by without comment.

Now for all those watching about to turn this off, I do think that Scandoval, as the scandal has come to be known, is one of the most interesting types of storytelling that can exist, and one that does happen in some scripted narratives, though with varying degrees of success.

So today, I’m talking about Scandoval, the Tom Sandoval cheating scandal that hit Vanderpump Rules, but from the point of view of storytelling and fan interation with story, rather than any kind of personal take on the whole thing, or a delve into the gory details, though I will provide details for those less aware of the whole event.

In fact, I think that’s an interesting part of this whole thing. One of the fascinating things about online interaction is how niche it can be for something that spans the whole world. I have many friends who also love a good amount of online time, and are often in similar circles to me. So while my phone was blowing up with reddit threads, discord messages, tweets and everything about what was happening over on the show Vanderpump Rules, those of my friends less reality tv inclined weren’t hearing quite all the same things.

So for those less in the know, here’s the scoop. The show in question is Vanderpump Rules - a spin-off of Real Housewives of Beverley Hills. The show started as a kind of work place drama surrounding servers and bartenders at the restaurant SUR in Hollywood, a restaurant run and owned by one of the stars of the Real Housewives of Beverley Hills, Lisa Vanderpump. The show gets kickstarted by a contrived discussion between one of Lisa’s co-stars at the time Brandi Glanville and Vanderpump Rules star Scheana. Scheana had once been a mistress to Eddy Cibrian, ex-husband to Brandi Glanville.

I mention this all for an important reason. Despite all the other names about to be mentioned in this scandal, and even how the show has unfolded and been discussed by fans, Scheana is the reason this show started, and remains a strange central figure despite all the classic arguments that occurs throughout seasons of a show.

For those not in the know, Scandoval unfolded when it was revealed that Tom Sandoval, bartender who was on the show from the beginning, had been cheating for several months on his long-term girlfriend of about ten years, Ariana, with co-star Raquel.

Now, a quick note before we delve into this scandal. Because my focus today is on storytelling, I will be using terminology which relates to this, such as plot and character. This is not becasue I am unaware of the very real affect this scandal has on many of the people involved. Reality television is a complicated field of discussion because while it is very real people, it is also in many ways manufactured and produced. Cast members come to producers at the beginning of a season with their intended “storyline” for the season, which is then directly discussed by show runners and producers. While these storylines can change drastically with an alteration in a person’s life, it is also something that is approached as story. Reality television still has to follow quintessential elements of storytelling and present the audience with expected beats and moments. This is why I will be using these terms, though I do acknowledge that it has had an impact on life outside of the show.

So, let’s dig into this scandal and the story that unfolded, and why it’s so damn fascinating to so many people.

I think the first important piece of story we should talk about is how the scandal became such a huge moment in reality television to begin with. As Andy Cohen pointed out in the reunion, there are very few, if any, cast members who have not in some way participated in some kind of cheating. But in these moments, the cheating was almost always an outside source. Most notably for an exaple was Sandoval’s Miami girl, who was brought in by a cast member to confront him on camera.

The only potential differeing point was when Kristen was revealed to have slept with Jax. Though this particular moment wasn’t necessarily a direct cheating moment so much as sleeping with a friend’s ex, rather than a friend’s direct boyfriend.

There are two improtant factors that led to Scandoval being such a moment. The first is the way the character development of the primary characters have unfolded over the years, and the second is the direct onversation it has forced individuals to have about levels of production.

Let’s take the first of these. There are three primary figures involved in this case: Tom Sandoval, Raquel Leviss, and Ariana Madox. Sandoval’s character was always one that was in a state of flux of understanding. He flowed from being in the wrong to in the right fairly fludily, and was never a figure that was an obvious villain character, as opposed to his friend and cast mate Jax Taylor who prety solidly filled the role of villain. When Ariana came on the scene as a friend of Tom’s, the timeline of relationship in comparison to when Tomw as dating Kristen was brought into question, though Kristen and Tom’s relationship was so toxic and confusing regardless that few seemed to care enough to chase the idea further.

After Ariana began dating Tom more solidly, the character development of the two of them began to change. Tom was far less often in the wrong (though still found himself screaming at women and hating Katie for seemingly no reason). Ariana’s calm demeanor seemed to have a particular effect on Tom, and the two became a cornerstone relationship that the audience could rely on. The various cheating rumours began to fade and become far more focused on the other male cast mates.

Tom’s character as understood in the show was quietly shifting over time, and allowing him a more comfortable space on the show and in the lives of fans outside of filming. This was all impacted by his relationship with Ariana, who was seen by many audiences and fans as someone who was the most relatable and normal of the crazy collection of characters who came to have a place on the show.

Their relationship itself was rarely brought into question by fans, though sometimes there was an attempt by people such as Jax Taylor. Tom and Ariana both did a good job of either not having issues in their relationship, or in not showing these issues on the show.

While Tom’s image was one in flux, both Ariana and Raquel’s was kept fairly firm. Ariana was open with her mental health struggles, particularly her struggle with depression, which appealed to many audience members.

Raquel came far more recently, showing up as someone dating James Kennedy. She was a strange figure to introduce to the show, as all outward appearance was of a young woman who was kind and naive. Audiences flocked to her while also questioning what she saw in the rather abrasive figure of her partner. As a couple, they presented an interesting juxtaposition: loud, drunk and aggressive vs the timid, kind and quiet Raquel.

Raquel’s character development was one some would expect from a story which introduce a naive pageant girl who had newly moved to LA and seemed unaware of how the city functioned. A person who started out unaware of everything and rolls over to please her abrasive boyfriend began to grow a voice, although a still admittedly timid one. She gave James an ultimatum regarding his drinking resulting in James becoming sober for a short amount of time. Later, Raquel breaks her engagement to James on account of saying she wanted to focus on herself and realise what she actually wanted in life.

In essence, the world was backing Raquel, and was rooting for her to have her win. After breaking up with James, she announced her dream was always to work with children with special needs, a dream she had put on the backburner to live in LA with her new boyfriend. This announcement furthered the audiences view of her as a kind hearted girl caught up in the crazy schemes of the cast of Vanderpump Rules.

It is precisely this view of her that was disintegrated by the news of the cheating scandal. Prior to this news breaking, there was a small scandal of Raquel being seen making out with a cameo appearance by a character named Oliver, who turned out was married. However, the naive Raquel was easily excused: an unscrupulous cheater could easily lie about his circumstances to convince Raquel that all is okay.

But Sandoval is different, to an extent. Raquel was not only someone who personally knew Ariana, but was actually friends with her in a way which seemed genuine on both sides. Ariana looked after Raquel during her time with James, and even frequently stood by her during Raquel’s tricky newly single moments.

But as a say, this was to an extent. And this is where the second bit comes in. A reality show’s story is one that is crafted, and had many hands involved. For starters, a reality show’s success or failure initially comes form the abilities of the casting director. Characters need to be interesting, whether its scripted or not. People watch shows week after week because they are interested in the characters, and how those charactersations turn interactions into compelling plot. This is the same for reality tv.

Then there are the producers and show runners. These individuals control the story as it unfolds, whether that be in poking cast members to action at specific times, or to ensure that the storylines are run at an effective pace. Producers work with cast members to push for storylines to unfold the way the producers want them, at the times and ways they want them to.

But there’s an interesting thing that happens when someone has been on a reality show for a long time: you learn how production happens and how to produce yourself. Self production is a huge conversation in the world of Bravo, and a frequent topic on the Housewives franchise. By self-production, fans mean that cast members have become so aware of how the production works that they actively control the things they say and do in specific circumstances in order to control the way that production can display them.

The control over production, and the way that both Tom Sandoval and Raquel worked to control their image on the show throughout the affair, and Sandoval claimed that there was self production between Sandoval and Ariana for years to cover up issues in their relationship. Knowledge of this self production has invited audience members to uncover small comments and actions to study and analyse in hopes of uncovering some kind of kernel of the truth.

Which brings me to the best aspect of the storytelling about Scandoval. The invitation for audience analysis, the detailed development of storylines and character development that has unfolded over the course of ten years of content, and the large amount of knowledge and details of the cheating scandal that has slowly become known before it was unveiled on the show led to a complicated relationship between the show and the timeline.

By timeline, I do not mean the detailed discussion of what happened it which order for the relationship between Sandoval and Raquel. Rather, I mean the relationship the audience has with the knowledge of the story.

Reality television has a unique relationship to time that very rarely can compare to scripted entertainment. Dramatic Irony is the term typically used for when the audience has knowledge that is not privy to the characters, which is something that happens fairly frequently in reality television. Because there is so much time that passes between the time of filming a show and the time that it airs, there are often times that important information about the figures is already known. In the Kardashians, we know that Kloe’s relatinoship has ended before it has on our screens, for example.

In the case of Scandoval, the dramatic irony is increased in intensity. We as the audience have the knowledge that the cheating happened before the cast does, but we also know that it’s happening during the time of the events as well. So, for example, while cast members were arguing over whether Raquel should be considered a mistress because of her makeout with Oliver, the audience is knowing about the fact that she is one with Sandoval at that moment, even though that wasn’t what was being discussed, and knowing that they will find out all about it soon. So we’re arguing about something that happened, that they dont’ know about yet, but that is actually happening at that time as well.

The complciated weaving of timelines and knowledge and when this knowledge should be utilised and understood and when it shouldn’t creates an interesting weave of dramatic irony for the audience to engage with in the typical conflicts that pop up on the show. Instead of arguing over the nuance of Raquel’s relationship with Oliver, for example, we are instead arguing this point while also thinking about the more detailed and extreme issue that will be known soon, even though it was also going on at the same time.

Basically, all this leads to the fact that this is a fascinating way tot tell a story. Even for scripted narratives, dramatic irony needs to be looped on severla levels to get the extreme amount of complicated relationships the audience can have with the text, and it all just kinda fell in the laps of Bravo.

The complicated networks that tangle up the development, enjoyment, and way that the audience is receiving the narrative leads to a far more interesting story of scandal than we have received from reality television in quite some time.

July 11, 2023

The Digital Campfire

One of the most magical places to be is around a campfire. Sipping hot cider or hot cocoa, bundled under a blanket, watching flames lick around logs, while listening to the stories of the people you love and care for. Somehow, the stories are somewhat different than other stories. Maybe it’s the way the heat radiates from the flames, or the way those who tell stories gather around. Maybe it’s the way the campfire entrances; it brings people closer to the light because we can, innately, feel the darkness that circles behind us.

There is a magic to the campfire. It saves us from the darkness, but it also makes us feel like we are closer to that darkness at the same time. The stories we share also bring the darkness closer to the fires, but the fire is always there to keep it from being too close. It protects us, in a way, reminding us that the darkness can’t actually touch us - it’s just the stories that make it feel closer.

Essentially, there is a type of “as if” play going on. We talk about the things that go bump in the night, feeling that they’re just behind us in that encroaching darkness. But by the time the story is over, and we return to the safety of the fire, it’s all gone. When we retreat to our tents, let the fire slowly burn out, the things we jumped at during the stories do not come and get us - the sun rises, and we are not surprised to see that happen. And yet, when we are there, in the dark, it all feels like it’s there, waiting in the encroaching darkness.

We play with reality when we tell stories around a campfire. In that moment, we play on the fact that the flames dance, and the darkness lurks, and we give ourselves over to that. The crunching of leaves is no longer a rabbit or deer, but a monster brought to life from the narratives woven over the fire.

I talk more about the digital campfire and digital monsters in my book Digital Monsters.

This is also the digital campfire, the place we gather to tell stories online. We may not be bundled up with a blanket and hot cocoa - though we absolutely might be - but the affects are the same. The realism of the narratives, the way we give ourselves over to the as-if’s of the narratives, causes the heart to pound a little faster. But when you leave the campfire, packed up the tent and gone home, the pounding is gone and the narrative lingers as a fun story that entertained you on a clear and cold night.

We, as humans, love this campfire, and the online environments we now find ourselves is are not devoid of the things we need. We need stories because humans are just big bags of stories wrapped up in flesh. When we move locations, we seek these types of experiences. We tell stories at a cafe in a way that makes our friends lean in close and react with joy or dismay or disgust. We engage with narratives with a willingness to belief, rather than a distrust and suspension of disbelief. And narraives play with this reality when it draws us closer to the darkness, or plays with belief with the way we love to delve in, no looking back. The internet is no different, and its in some spaces that we find this digital campfire to snuggle up and listen to a good story.

The play with reality and belief is fun, but mostly as a way through which the narrative can truly thrive, rather than an engagement to fool or trick. Beyond that, most participating with he narrative are in on the level of reality, and know the story to be fictional. It’s just a fun story to tell around a campfire.

June 27, 2023

How the Body Tells Stories

I wanted to take a moment today to talk about how the body tells stories. Now, this is big, and one that we can talk about in a variety of ways, including the way we tell the stories of ourselves with our bodies, to the way that bodies perform narratives. Today, I’m focusing on the general idea of bodies telling stories, and the way that happens. The more specific stories that bodies tell we’ll reserve for another time.

When we think about stories, we immediately think of the written stories first. We think of books, or blogs, or scripts of movies. We don’t think about the more inherent narratives, the stories that we tell in more intricate, performative ways. But mythology, and storytelling more generally, involves many kinds of narratives, and stories that can be akin to written narratives. It can involve oral narratives, bodily performed narratives, and narratives about narratives.

I’ve talked before on this blog about implicit mythology, but I have previously used it to understand the ways that playing video games can be a type of storytelling. But implicit mythology also helps us to understand other forms of narratives. Jonathan Miles-Watson, for example, used implicit mythology to understand that which both inspires and develops personal narratives of experience. The narratives around us become bodily understood and interpreted.

It is through our bodies that we see the world, and through which we are seen by the world. Seeing me is also seeing my body. Anthropologist Mary Douglas wrote about how we all have two bodies: a physical body and a social body. The social body in many ways controls the way our physical bodies are read and understood by the people around us. Our physical experiences and understanding of our physical body is always ‘clothed’ by our social categories and social worlds. In many ways, there is no such thing as a nude body, because we are always clothed in these thoughts and considerations. Douglas’s two bodies are always in interaction and communication with each other, constantly reinforcing the categories of one on to the other. Essentially, our bodies are more than the biological mechanisms they are. They are also social tools for communication and categorisation.

The body, therefore, is the primary model through which we tell stories because it’s the primary form through which we exist. As I sit at my computer, writing this blog post, it is still through my body that I write this. My hands move, my back aches in my chair, but also I feel the rush of my heart when I know exactly how I want to phrase the bit I want. Our bodies are the way we experience our narratives, because we are our bodies.

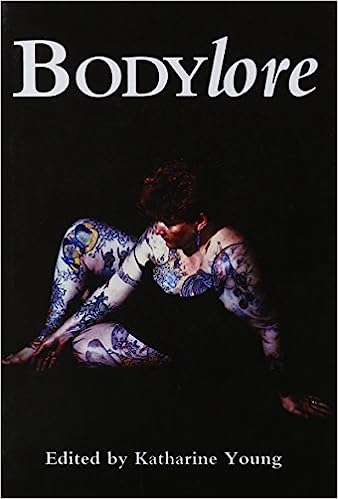

There is a subset of folklore studies that focuses on other forms of storytelling than traditional words. Bodylore, as its called, refers to the way that the body has its own text, and is the central local in which culture and tradition is received, understood, and transmitted. We do very little without our bodies, including the way we tell and understand stories.

Bodylore highlights some of what we’ve already talked about: how the body is central to communication and identity, and is the central form in which we engage with and interact with the social worlds around us. What bodylore centrally understands is that the body is inherently preformative, and is the way in which we transmit and communicate our identity to other people around us, through these performances.

If it is through our bodies that we taken in narratives, that we relate to narratives, then the body can be a central piece in the transmission of narratives. It can be the tool that we use to tell stories, to communicate ourselves and our stories and the stories that we love.

June 19, 2023

Shadow Texts and the Ancient Magus’ Bride

It’s pretty normal for media to refer to older narratives, particularly mythologies. Perhaps it’s just my own interests in pop culture, but a lot of the media I’ve been consuming lately is referential. Most on the top of my mind has been the second season of Ancient Magus Bride, which obviously has it’s references and allusions. In its first season, it had characters stripped from folklore and mythology such as the Wandering Jew. In the second season it now has allusions to esoteric magic teachers from the 1500s. I absolutely love this stuff, and enjoy either recognising references or fervently looking it up to learn more.

When we talk about the intersections of mythology and popular culture, there are two ways we can approach it. The first is looking at how mythology is represented in popular culture, and the second the way popular culture is mythology. Typically here on Incidental Mythology, we talk a lot about the second - the entire name Incidental Mythology is based on this understanding, how our popular culture is our mythology incidentally. But today, we’re going to talk more about the first - the Pop culture narratives that draw on mythology directly and purposefully, whether as direct representation or in allusion.

On my blog, I’ve covered some elements of this in the past. I wrote briefly about the Wild Hunt in both folklore and the Witcher, and also chatted about the representation of the Wendigo in pop culture in comparison to Native American folklore. But on this channel, I haven’t spent a lot of time on this first element, but it’s an important facet of pop culture and mythology that I think we should occasionally touch on. And today, let’s chat about how we can see different sides of this in Ancient Magus Bride as our primary case study.

The first primary question to consider is why contemporary storytellers rely on old narratives and myths in the first place. If people are writing new stories, why dull your creativity with old narratives you didn’t craft? I am, I hope people know, asking the question in the way someone would be annoying, and I do not think that using these narrative is any dulling of creativity, but let’s chat about this.

Sometimes, the use of mythology in popular culture is as a tool of exoticisation. A good example of this from contemporary video games would be the use of the Wendigo and other indigenous stories and beliefs in horror games, and particularly Until Dawn. The use of indigenous stories helped to create a sense of the exotic and an aura of mystique around the primary threat of the game.

In his book Orientalism, Edward Said talked about the exoticisation of the East. Orientalism is the exaggeration of cultural difference, and based on an presumption of Western superiority. An important part of Said’s argument is the way culture is communicated and understood by the one doing the exoticisation. Said points out that often the sources people would raw on when picturing these other cultures would be literature or sources written by Westerners, and continuing to draw on these sources rather than to pull form the culture themselves to help paint the exoticised culture as one which is unable to defend itself or paint their own narratives.

In more nuance categories, we can talk about the use of Norse mythology in popular culture, especially in pieces like God of War. Most knowledge and stories from Norse mythology are drawn from the Prose Edda or Poetic Edda, written down by Snorri Sturluson, a Christian missionary. In other words, the stories of a religion and culture was being written down by someone who was not an adherent.

While it can be fairly simple to see the use of indigenous religions and beliefs being used as a form of exoticisation, which is often the case for the Wendigo in popular culture, it can also happen to older texts and cultures which predate religions and experiences now. I think sometimes mythology can be seen as unproblematic to borrow from because they are assumed that there is no one left to potentially offend. This does, of course, ignore contemporary adherents of pagan traditions.

Something a little different is happening in the case of the Ancient Magus Bride. The original text, the manga series written by Kore Yamazaki is a story that takes place in England. Because of it’s setting, the mythology and folklore that is often being drawn on is inherently Western in nature. She references the Wandering Jew, a Christian piece of folklore, fairy queen and king Titania and Oberon, and a silkie to name a few. The sources being utilised to learn from in order to do the writing is inherently Western, rather than repeated elsewhere and by others. And the interplay of intercultural communication going in the other direction can make things a little more complicated.

In this instance, I think it may be useful to think of the mythology being drawn in Ancient Magus Bride as one which relies on shadow texts. Barry Brummett uses the idea of “shadow texts” to understand the way intertextual communication works, particularly in popular culture. Shadow texts are the texts we bring with us when we experience new texts. These elements that we bring forward with us help us to determine, under-determine or over-determine, the new text we are encountering. Sometimes, our shadow texts are things that the writer or creator of the new text has no control over. When I come to a new video game, for example, I’m immediately going to be comparing it to other games I’ve played, and a designer can’t think about every game that anyone has possibly ever played when designing their game.

Shadow texts can, however, be utilised by writers for two primary purposes; to provide focus, and to provide legitimisation. Let’s talk about focus first.

Shadow texts can be referenced directly and obviously by pieces of popular culture in order to guide the audience to focus on what aspects of the show or piece of media the writer wishes them to focus on. This is most obviously done through the use of allusions and direct references: characters who have names like Oberon, or references directly to folkloric stories of the selkies, for example.

While we still are bringing to the Ancient Magus Bride other shadow texts, like other anime or other urban fantasy stories, we are also focusing in on what shadow texts are being directly referenced, such as fairy stories, folklore and mythology. It means we pay more attention to what these shadow texts bring to the table more than the others, and think about these other elements and how they connect to the cultural knowledge that we already have.

That being said, the writers who utilise shadow texts in this way can’t always rely on cultural knowledge of shadow texts to be the same or equal between audience members. I think of the first Norse God of War for this. Most people I knew outside of mythology research circles were not as knowledgeable about Norse mythology, especially in the way that it was being utilised in that game. While I was able to see elements of the stories coming together, most notably the story of Baldur and the Mistletoe, others were not as aware of this.

The use of these texts without the cultural references being clear is not always necessarily a miss on the side of the writers. For the writers of God of War, for example, they were able to utilise an old story that some may recognise, while also presenting it as a twist to others. This means that the game is helping to replicate original storytelling, while still putting their own spin on a classic tale.

This leads us to the second way that shadow texts can be utilised: as a form of legitimisation. One of the complaints that happens when I’m mention my primary thesis of pop culture as contemporary mythology, is that pop culture doesn’t have the length of time that is given for what we think of mythology. Mythology like the Norse and Greek and Egyptian is all from a very long time ago, and this distance of time gives it a sense of legitimisation. These stories are more important, more impactful, because it’s more old. They’ve stood the test of time, they’ve demonstrated their resilience because we still know them.

Popular culture like the Ancient Magus Bride uses this legitimisation as part of their background. Directly referencing these narratives provides shadow texts which not only provide flavour but also strength, resilience and legitimisation. It backs up the story as one that can situate itself in between these other narratives, and provides a fuller background than what the writer initially provides.

Let’s quickly go back to God of War. While some may think the lack of cultural knowledge in some of the audience as a failure on someone’s part, it actually provided the writers with an ability to situate their game as an opportunity for individuals to be newly experiencing the stories in Norse mythology. They become the new storyteller for an old story, creating a place for their game to exist among the rest of the storytelling experiences of Norse mythology.

For Ancient Magus Bride, the legitimisation is less in the storytelling directly. While this may have been the first instance that some may have encountered selkies or banshees, the show touches on these elements briefly. This means that they move on too fast for them to situate the story in a place of new storyteller. Rather, they are placed as interpreter and relation.

This type is actually quite common in urban fantasy stories more generally. The writers use the shadow texts at their disposal in order to form new interpretations on the old, and present their version as a version that lives amongst other understandings. Rather than being a storyteller themselves, they are more the one who whispers the translations of the story in the ear of the listener.

In either of these instances, the cultural knowledge of the audience provides an interesting relationship between shadow text, primary text, and audience. This intertextual relationship is interesting and complex, and often comes out in the form of fan theories. One of my favourite places to go for fan theories is the Ancient Magus Bride fan subreddit, where people delve into not only the story of the anime, but also the stories which surround the anime as shadow texts. Fans explain aspects of the narrative that are still yet unexplaned through these shadow texts.

There’s a lot that can be said of intertextual relationships, especially ones which are less directly text-based. Anime, as a visual artform, has the ability to show us shdow texts as well - they can provide visual references as well as spoken or written. And each of these can be employed by the writers and artists for very specific purposes. Using shadow texts effectively, and understanding their existence, can be a wonderful tool for the writer. And definitely something a mythographer should be looking out for.