Vivian Asimos's Blog: Incidental Mythology, page 11

January 11, 2022

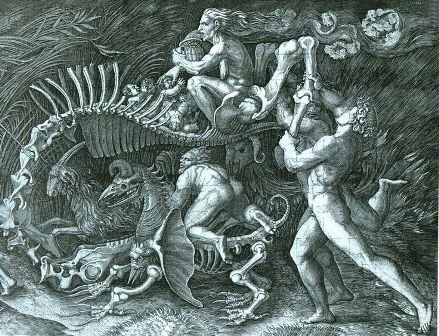

The Wild Hunt, in the Witcher and Folklore

The Witcher 3: the Wild Hunt heavily features the folkloric narrative of the Wild Hunt, if that’s not obvious by the title of the game. In the Witcher 3, our main character Geralt of Rivia is searching for Ciri, his adopted daughter, who is being sought after by the Wild Hunt. The true problem facing Ciri is the knowledge that the Wild Hunt never stops, and never relents, until they catch their prey. The final battle of the game is with the leader of the Wild Hunt, Eredin Bréacc Glas, in order to truly let Ciri escape her fate.

I wanted to spend some time talking about the Wild Hunt, because it’s actually something that only just ended for many areas of the world. That, and I’ve always really loved the story of the Wild Hunt. The problem is that there isn’t very much solid we can say about it – the Wild Hunt is different for many around the world, and even then the story is short and only shared in small whispers of its existence.

The Wild Hunt in the Witcher.

The idea of the Wild Hunt is found in a few different locations. We can see traces of it’s story in France, England and Wales; in Eastern European countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic and Russia; and in Germany.

The Wild Hunt was first named as such more broadly by Jacob Grimm, who recorded a few different tales of the Wild Hunt in different areas of Europe. Jacob and his brother Wilhelm were both academics – they were linguists, folklorists and ultimately ethnographers. The stories we think of as being “by” the Brothers Grimm are simply folkloric stories from Europe – primarily Germany – that they collected. Their books also have some levels of analysis and comparative folkloric analysis.

Because of that, the collection of the Wild Hunt by Jacob Grimm crosses ethnic and community boundaries frequently, jumping from area to area sometimes within the same paragraph. Grimm’s primary understanding of the Wild Hunt, to pair it down to its basics, is that the leader of the Hunt was always based on a semi-historical figure heavily associated with hunting of some form. And if that sounds like there isn’t one set leader of the Wild Hunt, then you’d be right. The leader is different across space and time, constantly shifting and altering. But like the hunt itself, the leader and the hunt is never fully gone.

Most of the references, particularly in Germanic folklore, is Woden, a god-like figure also associated with Odin. In fact, in Scandinavia, the leader of the Wild Hunt is sometimes a figure of Odin, and sometimes Odin himself.

"When the winter winds blow and the Yule fires are lit, it is best to stay indoors, safely shut away from the dark paths and the wild heaths. Those who wander out by themselves during the Yule-nights may hear a sudden rustling through the tops of the trees - a rustling that might be the wind, though the rest of the wood is still.

"But then the barking of dogs fills the air, and the host of wild souls sweeps down, fire flashing from the eyes of the black hounds and the hooves of the black horses"

Kveldulf Hagen Gundarsson (Mountain Thunder)

The Wild Hunt in many stories runs during the Twelve Days of Christmas, but in other times it’s constant. In both instances, you can tell when the Wild Hunt is on because you can hear it in the howls of the wind. Here you can also see some of the connections to Christmas. In my Krampus post, I mentioned there was a development in the production of Santa Claus as a figure – one which was at one point distinct from Saint Nicholas. The Wild Hunt plays into this development as well, but I may touch on that again in a future post.

Jacob Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology is where he spends most of his time focusing on the Wild Hunt. After exploring other characters associated with the Hunt, such as Hackelbärend – a huntsman who went hunting even on Sundays, which resulted in him being banished into the air with his hounds – to the god Wuotan, or Woden, and the connection to Odin. He traces the hunt through various locations and with various leaders, and ultimately showing how the Wild Hunt eventually came to be led by a goddess figure.

The connection to the goddess-led hunt is important for two primarily reasons. Many contemporary Pagan groups understand a connection between the Wild Hunt and Hecate – seeing the goddess as being the leader of the Wild Hunt now. And we also see why the Wild Hunt’s connection in the Witcher is so important to be focused on Ciri – a strong female figure to take over the understanding.

I think the Witcher series in general is a good one for simply displaying aspects and stories in folklore and mythology in ways that I think are interesting and more-or-less true to form, and the Wild Hunt is no different. While the Wild Hunt in the Witcher has one figure as its leader - Eredin Bréacc Glas – the connection to Ciri also links the aspects and development of the female-led figurehead. But what about that Eredin Bréacc Glas? There are not many figures that it’s a direct relationship to, but it can be an amalgamation of multiple figures. In some stories, the Erlking – or someone akin to the Erlking – is the leader of the Wild Hunt. In pop culture, this is more present in the Dresden Files, but figures like the Erlking – a fiendish elvish figure who hunts children and other humans in the forest – can still sometimes be found connected to the Hunt. Eredin has a similar vibe and is elvish as well. His secondary names are perhaps a reference to the Welsh versions of the Wild Hunt.

Either way, what I think is interesting with the Witcher’s depiction of the Wild Hunt is exactly what this website is all about. Regardless of its truth or accuracy in its depiction or stories of the folkloric Wild Hunt, the Witcher has transformed many people’s understandings and the video game’s version of the story is now – for many – the version that stands as their main telling. If I may be so bold to say, the Witcher’s Wild Hunt has become the primary folklore for many, even if it only occurred incidentally.

December 29, 2021

Krampus

I wanted to do one more Christmas monster before I retreat away from the Yule time and into the dark expanses of January and the new year. I know that for those celebrating Christmas, Christmas has just wrapped up. But I figured that while you digest your mince pies and procrastinate getting rid of all the wrapping paper and cardboard boxes in your house, that we’d spend a little time on the big daddy of Christmas monsters: Krampus.

Well, I say the big daddy of Christmas monsters, but perhaps its more suitable to say the “big daddies” because Krampus is more of a class than an individual. Which means that there can be more than one Krampus – the plural of Krampus is Krampusse in German, or Krampuses in English. A Krampus – though I’ll probably just keep talking about it without the article – is just one of many, like how a vampire is different than Dracula.

There have been many different figures which could potentially fit the idea of what became Krampus, though under a variety of other names. In Bavaria, the word most associated was Kramperl rather than Krampus, and other areas of Germany also had their own names, such as Ganggerl or Gankerl. But around the late 19th and 20th century, the word Krampus became to be used far more widely than the regionally specific names. The growing uniformity to Krampus began to grow as the presence of Krampus overseas, particularly in the United States, began to also grow.

Krampus, the Anti-SantaWhat I love most about Krampus is how it exemplifies some of the specific elements of the Other in Christmas. It has grown to represent the countercultural during Christmas time – those who want to reject the contemporary Christmas-spirit will find comfort in Krampus, seeing it as a figure who goes against the jolly-spirited Christmas that has come to be the way we understand it in the United States and even the United Kingdom.

However, Krampus is a bit different than this. In fact, the history of Krampus is inherently linked to the role and growth of Protestantism. As Protestantism took over Christmas, so did the role of St. Nicholas, and by extension Santa. In the early days, Santa was not equivalent to St Nicholas – they were two completely different figures who served different roles. St Nicholas’s day is December 6th and is still celebrated in Germany and other parts of Europe by putting one’s shoes outside for the saint to come by and slip presents inside. Santa, on the other hand, would show up on Christmas.

In these earlier days, when the distinction was much clearer, St Nicholas was typically accompanied by some “dark companions”, for lack any better word. The Grimm brothers did a solid job gathering some of these stories. The most infamous of these would be Black Pete, a horrendously racist depiction of a Moor from Spain who beat ill-behaved children with a birch road. Sometimes, the threat was also that he would kidnap the children and take them back to Spain. Krampus was another of these companions. A Krampus would make its appearance the night before St Nicholas’s feast night or would be accompanying Nicholas directly.

Krampus as Christmas Horror

Krampus as Christmas HorrorChristmas Horror is not always something you see reference to but is actually not all that abnormal. It’s not just recent Hollywood B-movies which have captured the Christmas horror aesthetic – particularly one that you see with their own imaginings of Krampus. But actually, Christmas is the perfect time for horror and dark stories.

Christmas itself takes place during the winter solstice, the darkest day of the year. This time calls for snuggling close to fires and feeling the dark creep in. The lack of sun tied with the ongoing cold and winter season is not exactly something jolly – I mean, it’s a bit creepy really. The growing presence of the cold, the winter, the dark nights, and the dead trees all sets the scene for monsters.

Some of our favourite Christmas narratives are inherently creepy. In the United Kingdom, there’s a special love for A Christmas Carol, which is a dark tale of ghosts and hauntings even though its all on Christmas. Horror is not just something reserved for adults alone – horror can be engaged with on a childlike level of fantasy and imagination without harming the young ones. Ghost stories are always wonderful to tell among children when gathered around a crackling fire on a dark, cold winter night.

Krampus in Popular CultureI won’t list all the ways Krampus has appeared in popular culture, as it’s become more and more common. Some of the bigger mentions has been the 2015 film Krampus, a Christmas-based horror movie that features Krampus unleased on a neighbourhood to punish naughty children. Krampus has also been featured in video games, including the Binding of Isaac: Rebirth in 2014. He’s also been in novels, live action and animated television shows as well.

In fact, the growing presence of Krampus in popular culture, particularly American popular culture, has created a growing sense of dread for the original locations where the figure once started. His continued and growing presence has created a fear that Krampus will soon be fully removed from his original context in the growth of cultural appropriation in the attention brought to American pop culture.

December 15, 2021

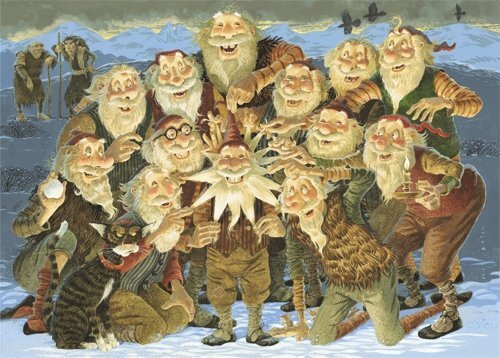

The Yule Lads

The Yule Lads are one of my favourite more playful Christmas-time folk characters. They’ve been captured in popular culture in Hilda, where the Yule Lads were after naughty children for their leader Gryla, who wants to eat them in stew. They’re also in Sabrina, and growing attention on the Yule Lads will only mean more appearances in popular culture as we continue to seek out newer yule-time folklore and myths to draw on for our popular culture. Christmas Myths in general are always a bit fun to get into, especially as they develop and alter over time and become incorporated into different aspects of popular culture. Of these various Christmas Myths, Christmas Monsters are always my favourites to talk about.

I thought it may be fun to spend a bit of time today talking about the Christmas Myth of the Yule Lads in their original form so you can feel superior to your friends when the appear next as you gleefully tell them all about the Yule Lads.

The Yule LadsThe Yule Lads come to us from Iceland. These strange characters are normally mountain-dwelling. But come down to the towns during Christmas. Their mother is another Christmas monster: Gryla, the ogress-witch of Icelandic mythology. The Yule Lads hunt the towns around Christmas to find naughty children, who they kidnap for their mother to eat in a naughty-child stew.

Gryla can be found in the Prose Edda, where she was described as a giantess – though, at this point, she has no connection to Christmas or the Yule Lads. Her connection to both happens around the 17th century. The description of the Yule Lads, and in particular their mother Gryla, was found in a poem by Jóhannes úr Kötlum. In this poem, the Yule Lads are described in number detail. Before this point, the Yule Lads were shared in the kind of muddy folklore that we’re used to, with no distinct number or names. But after the poem by Jóhannes, the Yule Lads became solidified: thirteen mischievous creatures who not only capture children for their mother’s naughty-kids-stew, but also cause all sorts of other types of mischievous trouble around town.

The Thirteen Yule Lads

The Thirteen Yule LadsSheep-Cote Clod is the one who tries to suckle the ewes on sheep farms. Gully Gawk let Clod go to the sheep because he was more preoccupied with cows. He likes to hide in the cow stalls and steal the milk. Stubby is known for being a bit shorter than the others, and he likes to steal food from frying pans.

Pot Licker, as you can assume based on his name, likes to lick pots. Bowl Licker has a similar inclination, but for bowls instead of pots. Door Slammer slams doors for the sole purpose of keeping everyone awake. Skyr Gobbler, our eight Yule Lad, likes to eat all the yoghurt, which is called skyr in Icelandic. Sausage Swiper swipes sausages.

Window Peeper likes to creep outside the villager’s homes and spy on the world inside – sometimes with the intention of stealing some of the things he sees inside. Door Sniffer has a huge nose and loves to steal various baked goods. Meat Hook steals the meat left out and has a special love for smoked lamb. And our last Yule Lad, Candle Beggar, steals candles – a once sought-after item.

From Christmas Monsters to Jolly Yule LadsAs their details demonstrate, the Yule Lads love to cause havoc, eat greedily of food that is not theirs, and generally be a big nuisance for the population of Iceland. The low-level stakes of licking bowls and stealing yoghurt is a strange juxtaposition with the threat of child kidnapping and harm that they posed to the naughty children would be eaten by their mother Gryla in a naughty-kid soup.

While the old stories described them as monstrous forms, as time wore on their monstrous forms began to change. They soon took on more human-like forms. Part of this alteration was also the changing role of the Yule Lads. While their mischievous nature remained for the most part, the more horror-side began to dwindle. The children-eating aspect, for example, faded away. Merchants would throw parties where the Yule Lads would simply be old men in traditional garb who passed out candy.

So, what was the point of the Yule Lads?It can be argued that there may never be a true point to any story, but if we were to hazard a guess as to the role of the Yule Lads in storytelling, we don’t need to look much farther than the time in which they appear. Winter is a harsh time of year for most creatures, especially humans living in Iceland. As humans retreated to the warm indoors to escape the harsh Icelandic winters, the dark and cold natural world took over.

As people retreated from outlying areas to be closer to their core farm and localised villages for the winter, the Yule Lads would risk leaving their seclusion to haunt the farms and towns. The cold nature is descending upon the world to reclaim their land. As the days get longer again, they too retreat back to their seclusion in the mountains and other surrounding areas.

Of course, the bonus of maintaining some kind of good behaviour in children is only a positive. Even our contemporary version of Santa Claus still has some level of good-behaviour threat to give children – be good, or Santa won’t bring you a present. While Gryla eating a misbehaving kid is definitely a bit stronger of a reaction than the Santa version, the core idea is still similar.

Not to mention that there are hints in other aspects of wintery reminders in the names and actions of some of the Yule Lads. Its no mistake that most of the Yule Lads are focused on aspects of food consumption: Sausage Swiper, Meat Hook and Skyr Gobbler are just three of the examples. These Yule Lads remind us to be mindful of the extra food we have over winter, and to take care of what food we have around the home during the harsher parts of winter.

The Yule Lads in Pop Culture

The Yule Lads in Pop CultureIt’s no surprise that the Yule Lads are beginning to get some traction and representation in different parts of popular culture. Like most pre-Christian figures, they have appeared (kinda) in The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, though it’s their mother, Gryla, whose mostly present in the narrative.

The Yule Lads were also featured in Hilda, one of my favourite shows on Netflix and one which I have done a video essay on as well. In Hilda, the Yule Lads are most similar to their representation in the 17th century poem: they are mischievous creatures who aim to disrupt as well as to capture naughty children for Gryla, a monster who intends to eat the children in a stew. In this portrayal, the Yule Lads were once human children who made a pact with Gryla to find other naughty children for her to eat and have thus been transformed into their current form. Of course, as is the case for Hilda, they solve the problem by giving Gryla the wonderful broth made by the Spirit Scouts to replace her child-stew.

And that’s our brief overview of the Yule Lads, a wonderful Christmas myth and Christmas monster to help tide you over until Christmas time. Just make sure you put your smoking meat away and check your bowls haven’t been licked before you make cookies in them!

November 30, 2021

Science Fiction, Magic and Mythology

A couple of days ago, The New York Times Books twitter posted up a tweet for an article about how H.G Wells was the father of science fiction. The resultant chaos online was a bit of fun to scroll through, with many pointing out how there were many many writers before him who wrote science fiction, including many women who are typically thought of as early figures in the genre, such as Mary Shelley and Margaret Cavendish. Others reached even farther back, bringing up ancient Greek texts. While the conversation around the erasure of women in many fields – with religious studies and especially the anthropology of religion being a big one – is something I could write quite a lot on, that is not why I’m bringing up this tweet.

Scrolling through the comments was fascinating – not because it was full of wonderful feminist memes, but because the comments followed interesting arguments about genre. When did science fiction really start? Some argued bringing up Mary Shelley’s name wasn’t proper as her work is horror, though others rightfully point out that books can have many genres, and that Frankenstein can fit both horror and science fiction at the same time. But the bit of the conversation I latched on to was a more quiet implicit argument going on between people even if they didn’t realise it.

At the core of many of these arguments was one central one: the differences between science fiction, magic, and mythology. I thought this was an interesting debate, and one I wanted to weigh in on. Science fiction, magic and mythology each have something to do with what I do – the intersections and relationships between religion and popular culture. When is science fiction actually science, versus a mysterious type of magic? When is mythology mythology, and can mythology embody science fiction?

In the classic words of any professor in the humanities or social sciences, I wanted to “unpack” this argument, because I think at its core, it teaches us a lot about science, and why science can be so readily ignored by so many – something that has balked many in the age of COVID.

Science FictionLet’s start our conversation here – half because it’s as good as a place to start as any, and half because the genre of science fiction is what got us to this discussion in the first place. To go back to the original tweet, if we’re to talk about where the genre of science fiction started, we’re going to have to confront the question of what science fiction is.

On the surface, this seems an easy question: science fiction is a genre of popular culture (including films, television and books to name a few) which involves complex actions, both currently possible and not, that is primarily explained by science.

In science fiction, the scientific explanation for what is going on in the world is paramount – it’s what’s necessary to set it apart. Travel on the U.S.S Enterprise needs to have Geordie saying something about nuclear fusion generators to explain why the ship has stopped and the crew are suddenly in a bit of a pickle. And it also needs Wes or Data to also use some reference to astrophysics or subatomic particles in some fissure as a way to solve the problem (not always but is as good as a demonstration of the genre as any).

What is notable about Star Trek: The Next Generation as our example is that science fiction’s explanations don’t always have to make sense. The science doesn’t have to be absolutely accurate to our understandings of contemporary science to exist as science fiction. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have science fiction that involves space flight to alternate galaxies – we can’t exactly do that right now, but we can pretend that science will get us there eventually.

It’s not realism that makes science fiction what it is either. A lot of work that is classically defined as science fiction does not exactly seem massively realistic, especially at the time of its original writing. Ray Bradbury, for example, wrote about dystopian futures which seem massively out of possibilities, and even references technology which seemed absurd at time of his writing. We have found a way to replicate some of these items in our contemporary time, but have managed to skip the bit of burning books (for now). Likewise, to go back to our Star Trek example, the leaps and bounds of both technical changes and social changes that is envisioned for the human future is a bit hopeful – to say the least.

Science fiction isn’t necessarily about it making sense or being realistic in that sense. Rather, what matters is in how the explanation appears. If the explanation is given through the voice of a scientist, it’s science fiction. This may be a rather crass and basic stance on the genre, but I think it sums up some of the general consensus on what it means to be a science fiction novel, or show. Where science is an answer, then we got science fiction. But when science is not the answer, it’s typically considered in the realm of magic.

MagicIn science fiction, amazing feats and actions are explained through science or technology. When science is not the answer, it’s explained through magic. Magic becomes the catch-all for amazing actions and feats which are “unexplainable”. Where Picard succeeds due to the scientific explanations of Geordie and the thrusters, Gandalf succeeds because he has wizard powers. We don’t really know how Gandalf does it, just that he can.

But magic can work differently depending on the location we find it in. From a literary perspective, magic can fit into a “system”, which can be either hard or soft depending on the level of explanation provided. Soft systems are a bit more malleable, and typically not as easily explained. Hard systems, on the other hand, fit very firm rules and followable explanations.

Diagram by Alexandra Darteyn. Click link for her blog on magic systems.

The magic systems created by Jim Butcher tend to be hard magic systems, both in the Dresden Files and in the Codex Alera. In any given situations, the reader knows what the confines are for the system they find themselves in. They know that when cornered, the protagonist can’t just use an unexplained magic element to get out of it – the magic has to follow the rules that they have already learned and constructed the world around.

In these instances, magic functions very differently to the “unexplained answers” aspect that sets it apart from the science fiction elements of fiction. Hard systems, and even some soft systems that adhere mostly to rules, begins to feel a bit more like a science in a way. It follows a set structure, and there are elements to magic that are possible or impossible depending on the structure and system that has been set up.

Our idea of magic as something inherently different or separate from science is an inherently social and culturally built conception, and has been partially brought on by the view of religions as the white and western scholars began to look at other cultures. Some early anthropologists used evolutionary theories to understand religion and how it can grow, seeing that the growth of culture goes from animistic views, to polytheism, to monotheism, and ultimately ending in atheism. Not only is this view not accurate to how many cultures and societies have developed, but it’s also inherently racist. These scholars would go and study polytheistic or animistic societies, typically in places like Africa, and equate them to what it was like for early white societies – despite an inherent difference in geography, society and history as context for how these ideas develop. They also saw these societies as inherently childish, being able to equate childish understandings of belief and thought to these other cultures.

While a lot of anthropology has progressed beyond this originally quite racist thought, our initial understandings of many things – from what is rational thought, what magic is, what religion is – all stems from this historical context. Even outside of academia, the understandings of rational thought is inherently tied to white supremacy and western cultures. Christianity, for example, is seen as a religion that makes sense, while some other religions – such as Haitian Vodun – is irrational and silly.

Essentially, magic has become a catch-all for beliefs or actions that white people don’t like to see as either religion or science. This also has an impact on wider social understandings of what these words mean and how we interact with the things we’ve categorised as each of these. Magic is essentially designated as the “Other”.

The role of magic is even more complicated by its position in storytelling. While our social understandings of these different words are affected by a lot of the contexts around us, the context of the specific conversation is also worth separate conversation. Stories have genres and contexts and understandings in and of themselves. My trigger into this whole debate started with misinformation about literary genre, and how genre categories are split and understood are complicated and just as filled with colloquial understandings and information as any other word and definition which can be discussed. We’re talking about storytelling here, and stories tend to be categorised into genres, even if the storywriters themselves may like to combine, destroy, or even reject genre categories. Magic, even when scientific, is found in fantasy as opposed to science fiction narratives. But what’s important to remember is that we draw these lines not based on general thoughts and feelings in the immediate – and these genres are typically drawn by marketers rather than literary scholars.

And the importance of storytelling leads us to also think about the history of storytelling. Rightly so, some comments on that original twitter thread suggested that some of the original science fiction did not actual start from Mary Shelley, but rather in ancient Greek texts – texts which some may describe as being mythological. I would even venture to suggest that science fiction being defined by the presence of overly-advanced science and machinery would also throw in mythology from India as well, where advanced machinery makes a lot of appearances, and would therefore predate even the Greek stories brought up in the comments.

MythologySo where does mythology sit in all this conversation? Does it have genres as much as other stories do, or is it its own genre, away from the others? Obviously, I have my own thoughts on the definition and understanding of mythology, but I want to continue through the strand of more colloquial definitions that we’ve done through the article so far, and think about how people typically think of mythology and compare that to these other thoughts regarding magic and science.

The colloquial view of myth is two-fold. The first is that “myth” is used to mean a story that is not true. Many online articles will declare that reading it will tell you “10 myths” about whatever subject you may wish to find. The second colloquial understanding is more applied to the fuller word “mythology” rather than the shorter “myth” – “mythology” is a story that is old and sacred, a narrative that is spun to tell the stories of gods or ancient warriors, or times before the ones we know.

An old coin representing Talos, an automaton in Greek Mythology.

The role of explanation continues to be important. Many of the definitions of myth that see it as these old tales of gods also see it as explanation. It explains the world. Why is lightening always followed by thunder? For myth, its’ the tale of how lightening and thunder are parts of the gods. For science, it’s the role of static electricity and sounds waves. In this view of myth, myth is bound to pass away in the age of science – science is the ultimate and superior form of explanation.

It is also inherently tied to religion. The mythological explanation is much like magic in that these are explanations not provided by science. And like magic, the mythological explanation is relatively unexplainable. This is not just in tales like where lightening comes from, but can also extend to aspects of healing and other parts of life. Folkloric remedies are sometimes tied to stories, and these remedies are passed down through generations. The same remedies are often argued as unnecessary in the age of science, but there are many examples where this may not necessarily be the case. When Western doctors came to villages in Africa for Ebola, they disrupted the folkloric type of quarantine that the people had already set up, and because of this actually led to more cases spreading than if they hadn’t messed with the system to begin with. There were also lots of folklore and myth around the healing powers of rosemary for HIV, a remedy which was often scoffed at by white scientists. However, after one group did some testing, they found that there is a chemical within rosemary which actually does prohibit the replication of HIV cells.

All this to say that mythology, like magic, is often viewed negatively in the age of science. It’s used to relegate other views, stories and opinions as less than. This is actually where the first definition of “myth” as falsehood really comes in. We designate myths as inherently false, without thinking more about what it is they are saying and why what they are saying really matters.

Science is not better than myth and magic, but rather a different form created by a different group of people. Magic has been relegated as such by the white colonial forces trying to Other the people they are oppressing. Myths are the stories told by these people. Science is the forces of explanation of the oppressors.

And this is why science can be easily ignored by people, even the age of COVID. Science does have a use, and a proper place of explanation. But it’s history of positioning itself between the Others has relegated it as separate and better, even if it’s not.

For science to truly survive, and for it to serve the betterment of those around it, it needs to learn to listen. To not Other those around them. And to learn that science is itself a form of magic and a type of mythology.

November 16, 2021

Repetition and Zelda’s Darkest Game

The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask is a standout game, and slightly divisive in the community. People either love it or hate it, and they either love it or hate it for the same reason: it's different. Before Breath of the Wild came out, the Zelda franchise had been wracked by the problem of the same. Zelda games fell into the rut of similar structure, which is quite appealing. You always knew what you were going to get with a Zelda game, and it meant that familiarity bred joy and comfort. But sometimes, difference can be a breath of fresh air. This was felt almost universally by the reset taken by Breath of the Wild. But Majora's Mask, has rarely been considered the same.

There are two primary reasons for this: the first is that Majora's Mask came out before the storytelling system was firmly established. The cycle of Zelda stories and their familiar structure was set by Ocarina of Time, which came out just a year before Majora's Mask release. Releases following MM followed the pattern of story set by Ocarina, rather than Majora. So even though Majora's Mask was very different than Ocarina, its difference wasn't as felt as Breath of the Wild because Breath of the Wild broke a cycle, rather than coming out before a cycle was set in stone. The second reason Majora's Mask is rarely considered on the same level of Breath of the Wild is because it has a much darker tone than the other Zelda games.

I wanted to take some time today to explore Majora's Mask, and really understand its darker tone. Some following Zelda games attempted to echo the tone or make it even darker. Twilight Princess, for example, tried really hard to fill the role of the "edgy Zelda game", but I just don't think it was as successful with this as Majora. While Twilight tried to emulate some of the darkness in their story, they relied too heavily on aesthetics to carry the tone. Majora's aesthetics, on the other hand, are not that different from Ocarina. In fact, the familiarity of the aesthetics is partly what leads to the darker tone, but we'll get more into that soon. But Majora succeeds were Twilight fails due to the darkness of the game being carried forward in two important aspects: story and player experience of story.

Majora's Mask came out just a year after Ocarina of Time. The tight timeframe led to some shortcuts in development. Almost all the character models are coped from Ocarina, for example. In fact, some of the even carry the same exact names, but others carry different monikers and fill different roles in the town of Termina than then did in Ocarina's Hyrule. While the borrowing of mechanics and character models were only due to issues in the actual process of game development, the impact they had on story, and more importantly the player experience of story, cannot be understated. The copying of the overly familiar in a sudden unfamiliar landscape is what helped to increase feelings of uncanniness.

Majora's Mask takes place immediately following the events of Ocarina of Time. While many Zelda games take the position of the various Links and Zeldas in the various games as being reincarnations of each other, Majora is different in its positioning as direct sequel to Ocarina. We start the game watching the child Link we constantly shifted to and out of in Ocarina of Time (a time travelling game for those who haven't played) slowly riding his horse through some woods. He gets attacked by the Skull Kid, another once-familiar face from Ocarina, whose wearing a strange mask. He steals Link's magical Ocarina, and scares his horse. After a chase through the woods, Link falls down a long dark hole, where, at the bottom, the Skull Kid transforms him into a much weaker figure: a Deku Scrub.

Continuing the chase regardless, Link ends up in the land of Termina, inside a clock tower, where the Happy Mask Salesman asks him the eerily famous line: "You've met with a terrible fate, haven't you?"

We are then tasked to defeat the Skull Kid, and save the Land of Termina from having the moon fall down on them (brought on by the Skull Kid) within just three days. Transformed by the evil Majora's Mask, the Skull Kid has wrecked havoc on Clock Town and the surrounding land of Termina, which Link works hard to reset and solve.

The story is more or less familiar at this point. A hero tasked with saving the land in a near impossible situation - sounds like a video game, and more importantly sounds like a Zelda game. But the three-day deadline does something really important to the story. At the end of a playthrough, the player (Link) must play a song to reset time, and we start, once again, at the base of the Clock Tower on our first day in Termina.

We'll get to that bit in a second. But we should first tackle the story as it appears on paper. Zelda games always have some great evil that must be stopped - most of the time taking the form of the evil king Ganondorf. And sections of this can be really dark, especially when we see some of the evil wrought to the world by Ganondorf. One of the things that really stands out to me personally is the first time we leave the Temple of Time as Link in Ocarina of Time. We have just transformed into an adult, jumping ahead in time by seven years. And the once bustling Market Square of Castle Town is now desolate, in ruins, and filled with shambling zombies.

Ocarina also had the strange world of the Shadow Temple, and the existence of the world under the well. This place was pretty freaky, and filled with torture machines and pools of blood. But the well and the Shadow Temple - and even the desolate ruins of Castle Town - are very horror-movie type of dark. There's blood and despair and death. Everything is freaky, but death-kinda-freaky.

Majora's Mask is... different.

Majora doesn’t rely on scary typical imagery of death. It’s not dark because of the presence of torture devices or pools of blood or zombies. It’s dark because of the confusing nature of the story – the familiar feel of a game that is twisted to something slightly different than we’re used to. And more importantly, the way we play through the game forces us to see the terrible works wrought upon the world of Termina, and then we must reset it.

Majora’s Mask is one of those games that’s full of different fan theories. I really enjoy sitting and looking through them all. One of my favourite was that each of the areas of Termina, which is comprised of four areas surrounding Clock Town, and the fifth of Clock Town representing the five stages of grief. The first area we encounter is Clock Town. Despite seeing the moon encroaching closer and closer each day, the townsfolk seem determined that nothing is wrong (denial). Even on the final day, when doom is very clearly present, the mayor still refuses to leave because he finds it all quite silly.

The second area we encounter is the swamp. The swamp, filled with Deku Scrubs, are furious because they believe the monkeys have stolen their princess. In retaliation, they are going to put a monkey to death. The monkeys enlist Link’s help to show them that the Princess ran away of her volition. Each Deku Scrub looks furious – the king literally shakes with rage. The swamp (Anger) shows the worst of what happens when wracked with anger and rage.

After Anger comes bargaining. In Snowhead, we run into the Gorons, who are suffering under a sudden wave of cold that has frozen much of the landscape, and even many of the people. At the heart of the community is a small child whose crying. The crying punctures the landscape and leaves a mark on the community and the area around the player as they explore the mountainscape. The community will do anything to stop the crying, and keep looking toward the recently deceased Darmani, a Goron hero. It's through Darmani's spirit that Link first inhabits the body and spirit of a dead character. Darmani's spirit is healed through Link and is therefore turned into a mask. Upon donning the mask, Link is transformed into Darmani.

On a side note, the mask transformations are really creepy and help to add to the strange, other-worldly dark atmosphere of the game. But we'll get to the mask transformations later on.

After bargaining, the next stage of grief is depression. And perhaps the most depressed area of Termina is the Great Bay, where Link interacts with and helps the Zora people. He first runs into Mikau, a Zora who is slowly dying on the beach. Link "heals" him, and through that healing ultimately ends his life and turns his spirit into a mask.

Through Mikau, Link helps Lulu, a Zora who has become so depressed she loses her voice. After giving birth to seven small Zora, all her children have been stolen. The loss of her children, as well as Mikau, her partner, she becomes swallowed up in her depression. Through Link's service, the children are recovered, and she is once again able to move on.

But ultimately, the game has to end with acceptance. Ikana Canyon seems to be a strange fit for acceptance, but after really looking at it, it makes sense. The Canyon is filled with strange beings who encapsulate death. One of the first figures Link encounters is a strange hooded one-eyed man. Link explores figures of death, helps skeletons and spirits of the long dead, and explores a temple for those long past. Ikana Canyon is a land of the dead, and here many have accepted their fate and are happy to live in their state of death. Of the four areas outside Clock Town, this is also the only location where Link is not given a spirit to transform into. Rather, Link is tasked with moving through the land of the dead rather than attempting to be like the living.

The presence of death permeates the entirety of the game. Link’s primary power in Majora’s Mask, as compared to other games, is his ability to transform into other creatures through a mask. However, he gets the mask by “healing troubled souls” – often those who are either recently passed, or in the process of dying. Link can then use these masks to transform into the characters, primarily Darmani the Goron and Mikau the Zora. His Deku Shrub version is theorised to also be the Deku butler's son, who we see has passed and therefore become a tree at the end of the game.

The mask transformation sequences are perhaps one of the creepier parts of the game, and one I used to skip past quickly when I played the game as a child. Link looks in deep pain, and even cries out in anguish during the creepily long transformation scene.

I'm personally unsure how deep the reading of the multiple stages of grief actually is. While some of the areas are far more clear, such as the anger in the Deku shrubs, some of the areas are a bit more washy in their appearance. The Gorons, for example, could be read as both Bargaining and Depression. The stages of grief theory is useful in considering some of the complicated natures of the different areas and the super complicated and quite frankly depressing state that many of the areas are in.

And this is where I think the darkness of the game comes from. The story itself is depressing, and the many characters are dealing with some very serious problems, including death and loss. But what makes the game dark is that at the end of solving everyone's problem, when Link is finally able to bring some amount of peace or happiness to those who are suffering - you have to reset back to the beginning of the three days. You have to reset time, reset their suffering, and once again have them return to a life of pain.

And that's what, to me, is at the core of Majora's Mask depression and darkness: the art of the repetition. The format of the game, and the way the player experiences the game, is, quite frankly, depressing. While the story itself is full of pain and anguish and suffering, which helps to bring darkness to the player, it's the player's experience of the story - the way the story is actively played out - that really solidifies Majora's Mask as one of the darkest games in the Zelda franchise.

Let's take, for an example, one of the more depressing side quests for the game: the story of Anju and Kafei. Kafei is betrothed to Anju and has also gone missing. The two are kept separate from one another because Kafei has been turned into a child by Skull Kid, and his wedding mask has been stolen. He ran to hide, too ashamed to reveal himself to Anju or his family. Through detailed work, Link finds Kafei, and works to pair him and Anju back together as well as to regain the wedding mask that was stolen from him. Through this questline, Anju insists on waiting for Kafei in Clock Town, where the moon will fall. After regaining the mask, the two finally get married, and wait to die together in the town.

Obviously, this ending is both sweet and terrible simultaneously. If Link spends the three days repairing Anju and Kafei's relationship, he is unable to save the town and the two die when the moon falls. However, beating the game - or essentially keeping the moon from falling on the town - also takes most of the three days. In the most successful timeframe of the game, the two are not brought back together.

What's more, after finally pairing the two together, the player plays the Song of Time, and resets everything - including all the joy brought to them, or the pain that has been erased - and returns to the beginning of the three days.

And I think this is where the true dark atmosphere of the game really is. Link is essentially powerless to the forces of suffering and pain that surrounds him. He is unable to truly help everyone at once - is never able to solve everyone's problem at the end of the game. To help most people, he has to forsake almost all others, including the saving of the entire town. To save the town, he must leave everyone to their suffering. There is no perfect run, and no way to save everyone.

Even the larger problems - such as Gorons suffering their losses, or Lulu whose loss of her child has rendered her speechless - never remains solved. In order to beat the game, Link quickly jumps to end goals of dungeons and beats bosses, which means that Lulu is left without her children or any knowledge of what happened to Mikau. And even in the runs where all this is solved - at the end of it all, the player is forced to erase all the good they have done.

In essence, the need to repeat the three days over and over again leaves the player unable to truly experience a happy ending to the story. All other Zelda games give you a happy ending, but even at the end of Majora's Mask - when Link has finally defeated the evil Majora's Mask - there is still pain and suffering and fear in the world he traversed through.

November 9, 2021

Cosplay as a Subversive Act

As is my usual lately, I've been thinking a lot about cosplay. My research into it has been fairly consistent, but that means that it's a slow growth which comes from a lot of reading incredibly different and somewhat unrelated material and then spending another chunk of time figuring out exactly how it all works together. And meanwhile, I'm busy working out logistics of more fieldwork and more interviews to make sure that what I think I'm seeing pairs up with how people are actually experiencing their cosplay.

One of the more interesting aspects of cosplay that I am beginning to uncover is just how subversive of a performance the act of cosplay actually is. Cosplay's subversion lies in the alterations of the narrative, enacted by individuals who have agency over narrative, performance, and storytelling. So I wanted to spend some time today getting into just how I see cosplay's subversion happening, and how this works in the larger context of anthropology and the world outside cosplay.

Cosplay and StoryThe best place to start is potentially the place of story. Obviously, cosplay begins with story. It starts the minute a cosplayer watches a movie, a television show, plays a video game, and connects innately with a character. The connection can occur for a variety of reasons, some which are incredibly personal and individualised, and others that can be for practical reasons. One cosplayer has commented that they typically gravitate toward cosplaying characters who have characteristics they want to embody. Other cosplayers enjoy particular styles of characters. One I chatted to said she prefers cosplaying characters who are very young girls, particularly Lolita style mostly because she sees her own body shape as fitting that style of character, though she also finds them quite cute.

Whether it’s because of their practical style or their personal connection to the character’s personality, the cosplay is chosen from a standing narrative. The character fits within this narrative and fills a particular role. The character has a particular personality, and a way of holding themselves which needs to be as present in the performance of the cosplay as the character’s outfit.

In one of my conversations, a cosplayer actively complained to me about when cosplayers don’t perform their character properly. Her primary example of this was when she attended a con and saw a group of people all cosplaying as Sasuke from Naruto. She complained about seeing them “jumping around” and acting “silly” in a way that she saw very unfitting to Sasuke’s character. For her, the processes of cosplay were seen as an inherently long and difficult process. In fact, the processes were precisely what set cosplay apart from the simple act of “dressing up”. If you’re going to go through that much effort to put together a cosplay, according to her, then you may as well do the extra effort of acting like the character as well.

Sasuke Cosplay

Other cosplayers echoed similar sentiments. When discussing the aspect of having different body shapes than the character’s body, one cosplayer said that it wasn’t about things like quality of costume or how exact the physical representation; the importance was on the characterisation. How well did the cosplayer demonstrate the character within their body?

The idea of telling a story non-verbally is not very unique or new. Any dancer will tell you the importance of storytelling without words - the way they move their body around air, or other bodies, is done with the utmost practice and purpose. Each movement is done to tell the story they have plotted out and intend to. When chatting with Nerdlesque performers, the importance on the "story" being told was heavily present. Each act was communicated to me as a story - a narrative they were crafting with exacting purpose, and this purpose was effectively communicated even to a non-practiced viewer like myself.

Stories are always told in a variety of ways. Even traditional narratives were told with more than just words. Performers (and I use this word as opposed to "actors" for a reason) may don a mask and dance or move about in other ways to tell the story of the character whose mask they've adorned.

Cosplay, in more than one way, is a mask performers wear. They adorn themselves like the character, and like the performers of old mythic tales, they must also take their performance seriously and act the part to the best of their abilities. Cosplayers, like other performers of narrative, have agency over their story. The story is not told passively through them, but actively. They choose to tell the stories in the ways they feel most compelled to through the presence of the narrative in their own limbs. And because the story is always given to performers with this level of agency, the story is also capable of being subverted in order to fit meanings or interpretations the performers wish to communicate.

Story as SubversionAs many of you who have been kicking around this blog for a while will know, I'm quite the fan of mythology and folklore. Everything I do - even cosplay - is going to relate to mythology and folklore at some point, and from my experience I never have to struggle that much to do it.

One important thing to keep in mind about mythology and folklore as we move is that folklore and myth can always be subversive. Sometimes this is very obvious and loud. More often than not, it's quiet and hidden, but always working away. This is because stories are from people - so much so that I believe that people are stories. We are defined by them, explained by them, connect through them. Every conversation I have with a friend is told through stories. Every cherished memory I share with my husband is a story I hold close to my heart. I could go on about this for ages, and maybe one day I will, but for now we can settle on the fact that to be human is to tell stories. And because we are social beings, and the stories we tell are, likewise, an intricate part of our social and cultural landscapes, the stories we tell are also social beings. As social beings themselves, they are just as influenced by our ideological foundations as everything else very “us”.

The downside of that is that our stories can cement social narratives of oppression. Patriarchy and racism can become embedded in our narratives. I talked a little about this in a video essay on the Myth of Maternity - the social myth often told in many patriarchal western countries that women are inherently maternal figures.

But stories can also change. And here we see how subversion can come into play. People do not just cohere to oppressive social systems - they also reject them. And when we start to reject certain power structures, we begin to see which narratives continue these structures and which don't. And we can change the narratives that reaffirm these structures in order to shift the narratives to fit a different ideology. I've spent a lot of time on this blog talking about Seth Kunin's jonglerie - where individuals juggle their multiple identities and connections to differing ideologies and through this emphasize or de-emphasize different parts of a myth to fit their various shifting ideologies and identities. Even though I talk about jonglerie a lot, I do it because it's an example beyond just myself of someone in the academic study of mythology seeing how storyteller agency can change a narrative. But understanding narratives as subversive goes beyond the singular example of Kunin's jonglerie.

Michael Kinsella, a scholar in the study of legends and legend-telling, also focuses his definition of legend and legend-telling as inherently able to be subversive. For Kinsella, legends are “context-dependent” and inherently “performative”; the function of legends are to identify and channel all the anxieties and ideologies of communities and folk groups.

As societies and folk groups change their basic ideologies and understandings, their stories change as well in order to accommodate these alterations in identification.

Horror drag example from performer Sharon Needles - a good example of some of the differences and subversions possible in drag and performance more generally.

Subverting Gender in CosplayThere are many different ways that cosplay can be subversive in their performance. The agency creators and performers have over their cosplays also means that they leverage some level of agency over the narrative itself. By transforming the narrative in their performances, the shifting interpretation being levied on the original narrative, or the criticism or reflection being asked of the original narrative, is also carried forward and impacting individual audience members as well as the performer themselves. Most of these social critiques or differing interpretations are concerned around discussions of, or representations of, gender.

Perhaps the most well-known way cosplay questions gender is in genderbending cosplays. In genderbending cosplays, cosplayers take a character who identifies as one particular gender in the original work, but then the cosplayer portrays the character as a different gender. The most common is taking male characters and portraying them as female, but the opposite also happens with female characters being made male. There are other gender transformations possible, however, including people taking binary identified characters (either male or female) and making them androgynous (some define this as making the character non-binary, but I choose the word androgynous here in order to avoid the common mistake of connecting non-binary identities to androgyny).

Gender itself is a typical social performance. Judith Butler uses the word "performativity" to describe how gender can be performed. Essentially what Butler is saying is that there is no inherent meaning to being a "girl" or being labelled as "girl" without the constant repetitive acts "girlness" that society enacts. Basically, the only way that being a "girl" carries meaning is when societies and individuals dress, act, and perform being a "girl".

To reconnect Butler to our previous conversation about story and subversion, we can see that these performative acts of “girlness” we can call “the myth of girlness” – a story of what it means to be a girl that is told and retold by society. And this performance of femininity changes and alters as our social understanding of “girlness” changes as well.

I mention all this because Butler’s idea of “performativity” is also at the heart of cosplay. When my cosplay performant complained about people not acting the part in cosplay, she was referring to their performativity. It is not enough to dress like a character, but you must reiterate all the other elements of their story in order to show what it means to be that identity.

Male Cruella-de-Ville by Connor Gray

This also combines with the social performance of gender when it comes to genderbending cosplays. Butler’s work spent time delving into drag. When performing female impersonation, drag performers are enacting these social narratives of “girlness”. By doing that, it forces the wider society to realise and recognize the narratives of “girlness” it communicates regularly. Drag by its nature is subversive – it demonstrates a subversion understanding of what it means to be “girl” and what it means to be “boy” by forcing different gender representations and understandings within their performance.

When performing a genderbending cosplay, cosplayers are not just relying on the performativity of their character, but also on the performativity of gender. Even though a defining characteristic of the original character – their gender – has been altered, the audience needs to still understand that the performance is of the original character. But combined with that, the cosplayer also has to perform gender. They have to tell the story of the chosen gender – or the chosen confusion of combined gender in the case of androgyny.

Genderbending cosplays can be chosen for a variety of reasons. Sometimes its because the cosplayer self-identifies as one particular gender, while the character is identified as a different one. The cosplayer will then choose to change the gender of the character to fit their own self-definition. Another reason may be for representation. This is more typical in male-to-female genderbends, where a character is originally male but is performed as female by the cosplayer. For these instances, the performer chooses to change a character due to a lack of options given by the original content of suitable female characters.

For whatever reason the cosplayer chooses to perform a genderbend, the genderbend subverts audience expectation on two fronts. The first is the expectation of the original character. By presenting the original character as true to form with the simple alteration of gender, it subverts our social understanding of gender being a definitive hierarchical definition of self. The performative narratives surrounding gender help to solidify typical social norms which work by suppressing and oppressing gender binaries and differences.

On the one hand, performing a character exactly the same with just gendered differences demonstrates just how little gendered differences can affect the importance of a character. A character’s strength or importance can remain unchanged even with the shift of gender. On the other hand, any performance of a gendered character is going to come accompanied by the performance of the gender itself. For genderbending, that performance is in the presentation of the character’s altered gender – performing the original character as inherently “girl” or “boy”. Like drag, this performance causes the audience to consider gender’s social performance.

Inosuke genderbend cosplay by Jessica Nigri

The performance of genderbended cosplay is one form of how cosplay can be inherently subversive. The performance of gender can alter our understanding of character and of gender. One act of agency on our understanding of gender an alter our interpretations of gender and character simultaneously.

I think, alongside genderbending cosplays, there are other forms of cosplay that are inherently subversive. Sexy cosplays, for example, are another form of cosplay that subverts expectation of narrative, character, and what it means to be sexy. But I think there’s something even more interesting going on here. I think that on some level, even the most basic act of cosplay – not shifting its appearance at all – can still be subversive in some respects because the act of storytelling itself can be subversive. And cosplay is, above all else, an inherently storytelling-based performance.

November 2, 2021

Baccano and the Art of Nonlinear Storytelling

Recently, I returned to the world of anime with a re-watch of the series Baccano!. Baccano has always ranked among my favourite anime shows, constantly challenging the position of number one with the Ancient Magus Bride and Cowboy Bebop. These are very different anime who rank in my number one spot for very differing reasons from one another. For Cowboy Bebop, the animation and story mixed with an incomparable soundtrack to create a masterpiece of complex human emotion mixed with violence and love and jazz. The Ancient Magus Bride takes all my love of mythology and folklore and gives it new life in one of the most visually beautiful shows I've ever seen. Baccano stands out from these two in its soundtrack being similar to Cowboy Bebop in its use of jazz, but isn't quite as well composed or pared with as well paired with parts of the show. Its characters are not as complex or deep as either Ancient Magus Bride or Cowboy Bebop. So why does it capture the imagination of so many people, as well as myself?

The interesting thing about Baccano is it's use of storytelling as an art itself. Baccano utilises non-linear storytelling to tell a complicated tale of a huge array of characters. While the characters are simplistic, the simplicity is part of the necessary exploration of storytelling in ways that are innately familiar to the viewer, calling on simplistic natures of folklore and myth to build archetypes which are both familiar and special.

Today, I wanted to spend some time really digging into the world of Baccano and explaining just how its non-linear storytelling works to connect to storytelling and mythology.

Baccano is set in the United States, and though it jumps around in time, the primary time period is Prohibition era with a focus on New York and Chicago. Despite this, the narrative is constantly shifting time periods as well as character perspectives, telling new views on the same story that impacts different people in different ways. The result is a somewhat disjoined narrative, which feels partially purposeful and partially confusing. Different dates get shown on screen, keeping the viewer on their toes correlating which characters are where at what times.

Some people have criticised the show for this, thinking it far more on the disjointed side than the "non-linear" side. This problem is compounded by the sheer number of characters. The cast is made up of at least twenty primary characters, with only groups of them interacting at different points in time. The various names and associations become difficult to track, especially as these relations shift over time - though this means the associations shift back and forth because the linear structure of the shifting nature of relations means that the non-linear storytelling takes this backwards and forwards depending on what time we're seeing.

But there is a method to the madness. The non-linearity, as well as the sheer number of characters, is prepared at the very beginning. The story starts the audience at the Daily Days, a organisation which fronts as a newspaper while actually working as an information gathering network. We start with Carol, a young girl whose sat in a pile of papers on a table, sorting through all the information regarding the incident on the Flying Pussyfoot - a transcontinental train. In fact, she throws out a date in which the incident all began. She is questioned, however, by the vice-president of the Daily Days.

What follows is a complicated exchange discussing the nature of stories and characters.

VP: What are you doing up there anyway?

Carole: Well honeslty, sir, I was thinking about the story.

VP: Story?

C: Well, I just can't seem to stop thinking about the series of strange events that began back in November of 1930, sir.

...

VP: What we record is neither unaffected information nor perceived information. It's the precursor to a conclusion. Tell me, you could have chosen any date on the timeline, but you selected 1930 as the point these stories began. Why?

C: Umm...

VP: How can one not have the answers to these questions and call themselves the assistant to Gustav Saint-Germain, the Vice-President of the Daily Days?

C: Uhhh...

VP: Perhaps you'd like some help?

At this point, the Vice President throws out two potential starting points: 1711, aboard the Advena Avis - a ship crossing the Atlantic; 1931, the Flying Pussyfoot, the transcontental train. He questions Carole about why she picked November of 1930 with all the information and potential starting points.

C: Well, Mr Vice-President, I was thinking about how to make the story easy to understand and I thought, well, the easiest way to see this is through our eyes, so I picked the time when the whole mess was first brought to our attention. Smart, huh?

...

VP: While that's the easiest way to see this mosaic, you should think about more than time, The characters are crucial elements as well. Do not neglect to consider them.

The two then consider several characters, and the audience gets their first glimpse of several primary characters we'll spend the rest of the show getting to know in greater detail. At the end, the VP gives a imporant piece of advice to Carole.

Still, Carole, depending on which of these interesting characters you focus, the same incidental will behave like the surface of the ocean, changeless yet ever changing, In other words, there may be but one event, but as many stories as there are people to tell them.

This exchange is one of the most important scenes in the entire show, because it explains everything about how the show is structured and understood. Every character has their own view on the events that unfolded, and every event that unfolded impacts a multitude of characters that the initiators may not even recognise.

We, as individuals, think of life as a story we are our own main character of. Because of this, we may think of events as ultimately impacting ourselves, when, in reality, they impact every body near us, near the event, and near others at the event, in a ripple affect that draws in far more characters than we would have considered.

Each of these characters also have their own way of understanding and structuring their stories. They are a different main character with a different way of organising the events they experienced. As storytellers, Carol and the Daily Days' Vice President must choose which view to tell the story of particular incidents, and we as the audience experience the story of Baccano through the difficult processing of how each view changes the perspective of the story.

But as I said earlier, the characters we view the events from are very archetypal. And there's a very important reason for this.

Baccano's Characters

Baccano's CharactersBaccano's story jump through time and location also means that there are a variety of characters for the audience to keep track of. These characters can be roughly broken down into nine rough categories: (1) The Daily Days, which has has several characters throughout the show gathering information or helping individual characters; the many crime families, inlcuding (2) the Gandor family, (3) Genoard family, (4) Jacuzzi's gang, (5) the Martillo family, and the (6) Russo family; (7) the ever changing group of the Immortals, which at times includes individuals from these other groups and at times does not; (8) Huey Laforet, one of these original immortals and his followers; and finally (9) the rag-tag collection of random other characters who somehow find themselves entangled, such as Isaac and Mira, a crime-committing couple.

I write all these out not to be super padantic about explaining each character's role, but rather to illustrate the sheer number of characters at play. Not all of these characters survive throughout the events of the show, but they all play some part - whether it be small or large.

But each of these characters are very basic in their construction. They're simple and easy to grasp the base of. But simplicity should not be mistaken for unthought or discardable. Baccano's characters calls back to traditional storytelling in myths and folklore, where characters are simple but meaningful. Characters in these more traditional stories are not simple for no reason - they are present in order to serve a particular purpose.

Carl Jung viewed myths and folklore as being universalisal stories - they weren't impacted by different cultural or social backings, but rather were easily applied across these boundaries due to the collective human unconscious. He saw the simple characters as falling into what he called "archetypes"- pre-set understandings of role, actions and goals that the characters enact in the narrative. Some Jungian archetypes are roles such as "the Hero" or "the Trickster" - each name denotes not only the type of character they are, but also how they can relate to other characters and story. The Child, for example, is not always necessarily a child, but can be childlike, but their primary role in the story is that of innocence. Essentially this means that the archetype of the Child allows us to not only know who they are as a character, but also how they fit into the role of the narrative.

While Jung's view on myths and folklore isn't my favourite, his in-depth look at the role of archetypes can be useful in studies like Baccano - and in particular to understand how simple characters can be intricate in their own right. Each of the characters in Baccano can be understood as archetypes - maybe not necessarily perfect to the archetypes laid out by Jung, but as archetypes more generally.

[image error]Eve Genoard, for example, is a good sample of the Child. Her pure innocence in simply wanting the best for her brother, despite her brother's rough actions toward both her and his own life. Despite the threat of many violent characters in the mafia surrounding her, she continues to act with a bravery that seems only to come from her position of innocently expecting the best of those around her.

The characters' archetypal nature also helps to allow multiple characters to shape the narrative not only in their interaction, but also in their relationship to one another. Ladd Russo is a great foil to the other hitman of the story, Claire Stanfield. Where Ladd kills ruthlessly and for the fun of it, Claire picks his targets with precision and with an understanding of a value to what he's taking or leaving.

The characters archetypal nature means that the narrative can flow between characters in complex ways - allowing the complexity of the character to be within their placement of narrative and their relationship to other characters, rather than relying on deep complexity of psychology. It's often a fallacy in narratives to think that complexity in characters needs to be in their fleshed out self-understanding. Simple characters are not necessarily not-complex - they are just simple to understand and relate to.

Baccano's Most Complex and Disjointed CharacterOne of my favourite memes is the role of New York as the other character in Sex in the City - not because it's inherently stupid, but because it's inherently true. Even though I've never really watched Sex in the City, I understand the idea of inherently deep complex growth not necessarily being tied to human characters. A similar function is happening in Baccano.

So we understand our human ensemble cast to be made up of simple - but not inferior - characterisations of archetypes. These archetypes work in foils to one another, as well as playing off of one another's needs and motivations to create a complex functionality of interrelations which lead to strange events. These events only happen due to the relationship between these characters and the ways in which they interact. The understanding of these events can also change depending on whose eyes we're viewing the event through.

Despite the vast array of characters, we don't follow one in particular as "the main character", or even have a solid individual whose understood as the singular "antagonist". In fact, sometimes protagonists in one view can become active agents working against another character - shifting roles to antagonist when the perspective shift occurs.

These complex ways to understand the roles of characters and events is what leads the narrative of Baccano to essentially require the simple archetypal characters presented. But that's not to say that there's no such thing as a character that isn't complex in the way we've grown to understand complexity. The complex way these characters flow from event to event, interacting with each other in growing complicated entanglements, leads to the true detailed character of the show: the story itself.

And this is where the non-linearity of the narrative really shines. Without it, the story would be appear to be just as archetypal as the characters - and individuals would flow out of our interest just as quickly as they came in. The non-linearity of the narrative requires us to actively pay attention to the growing cast, and the ways in which they interact. Essentially, the non-linearity of the narrative's presentation paired with the growing cast of archetypal characters means that the focus for the audience is on the story itself.

The most intricated and most disjointed character in Baccano is not any of the human or immortal characters encountered, but rather the story itself - the intricate interweaving nature of how characters interact and therefore impact the world around them is the primary character worthy of the audience's consideration.

Traditional storytelling and old myths work similarly. The characters in mythology and folklore are not meant to be massively in-depth characters with detailed complexity. They are meant to be easily understood because they carry with them the importance of a narrative - the story of a place, or a people's history, rather than their own individual journeys as a person. Similarly, a larger mythology may be possible to put in chronological order, but this is not necessarily how the stories are shared or experienced. The different tales are told out of order, and presented only when it seems important for the audience to experience them.

One of the reasons why Baccano is so enticing is because it replicates these more traditional types of storytelling. Its types of characters, story structure, and way of putting the story as the most important thing positions Baccano into a familiar way of knowing narratives.

October 19, 2021

The Meaning of the Pale Man

October is one of my favourite months because it’s the start of autumn and the bearer of Spooky Season. I couldn’t let October pass without doing some kind of video on something spooky. A few months ago, I did a series of short posts on my blog where I dug into the deep study of monsters from popular culture – which, in retrospect, I should have really saved for October. These were a bit short and quick, and I wanted to do one into one of my favourite monsters from pop culture but had far too much to say. So, let’s do that deep-dive now, just in time for Halloween. Let’s dig into the deeper meaning and importance of the Pale Man from del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth.

In 2006, Guillermo del Toro’s film Pan’s Labyrinth, or its original Spanish title El Laberinto del Fauno, was initially released. Pan’s Labyrinth is described as a dark fantasy, one that references styles of fiction like magical realism to blur the lines between fiction and reality. The magical fantastical world is not drastically different from the violent realities of the world. Each monster that the protagonist Ofelia faces is both scary and dangerous. Perhaps one of the most memorable and prominent monsters of the film is the Pale Man – a creature whose eyeball hands chase Ofelia down hallways with the intention of eating her. My love of monsters, and love of this film, meant that I had to spend this October explaining the Pale Man.