Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 60

January 6, 2014

do comics empower Black girls?

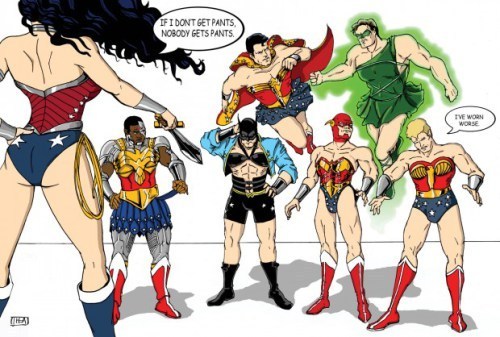

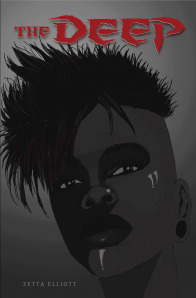

When I look at the work of most comic book artists, I generally think to myself, “That’s not my peer group.” I followed the comic strips in the Saturday paper when I was a child, and I definitely bought my fair share of Archie comic books. My brother sometimes shared his Spiderman comics with me but for the most part, I read traditional books. And now, as an adult, that’s what I write. When collaborating with the illustrator who made the sketches for The Deep‘s trailer, I made it clear that I didn’t want Nyla to be hypersexualized as women so often are in comics. I wanted her to be beautiful and powerful without wearing skimpy clothes over bulging biceps and/or breasts.

When I look at the work of most comic book artists, I generally think to myself, “That’s not my peer group.” I followed the comic strips in the Saturday paper when I was a child, and I definitely bought my fair share of Archie comic books. My brother sometimes shared his Spiderman comics with me but for the most part, I read traditional books. And now, as an adult, that’s what I write. When collaborating with the illustrator who made the sketches for The Deep‘s trailer, I made it clear that I didn’t want Nyla to be hypersexualized as women so often are in comics. I wanted her to be beautiful and powerful without wearing skimpy clothes over bulging biceps and/or breasts.

I’m a fan of the X-Men films and I was far more anxious to see Thor than Best Man Holiday, but the feminist in me knows that women generally don’t fare well in the imagination of most men. But I do have black feminist friends who are comics scholars and the POC Zine Project gives me hope that women are creating their own images to counter the many distortions. Kids constantly ask me when my novels will be made into films and I know just what it would mean to them to see empowered Black girls on the silver screen—girls who overcame obstacles AND survived till the end of the movie! But I also realize that my idea of an empowered Black girl probably looks a lot different than most teenagers’ idea. Ask them to name a powerful Black woman and they say, “Beyonce.” Not Michelle Obama or Shonda Rhimes or Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

When I created the character of Nyla I definitely wanted her to be a blend of confidence, intelligence, and beauty. I felt she was a natural leader, attractive but also intimidating, deeply loyal but also deeply insecure. Lyn Miller-Lachmann just posted an amazing review of The Deep and it’s clear she totally “got” Nyla:

Elliott creates a strong female character with many talents and many difficult choices. Her contradictory feelings toward the mother who abandoned her ring true and leave readers with much to ponder, especially if those readers are missing important people in their lives as well. Nyla’s toughness masks a vulnerability that the author makes clear early on; in the preface that takes place eight months earlier at an Air Force base in Germany, Nyla is sexually assaulted by an older boy at her school whom she believed she could control. This assault is what motivates Nyla’s father and stepmother to bring her back to the States, and to dangers they never could have imagined.

Lyn is an unabashed comics fan, and her passion for superheroes informs her fantastic middle grade novel Rogue. If you don’t yet know about The Pirate Tree Social Justice and Children’s Literature blog, you should definitely check them out. Here’s part of their mission statement:

…we are interested in books and writers that question and rebel against the status quo, argue for peace and reconciliation, take the side of the marginalized and powerless, and use creative solutions to overcome obstacles.

Can comic books offer all of the above AND represent women realistically? I suspect not, which is why I’ll stick with novels…

(Illustration by Cynthia “Thea” Rodgers)

(Illustration by Cynthia “Thea” Rodgers)

January 3, 2014

into the wild

I am ready to throttle the dog next door. Actually, I’d love to ask his owner why she thinks it’s ok to have a pet when she has absolutely no interest in meeting his needs. I’ve been working on “Fox & Crow” for a week now and I’m amazed it has taken me this long to write 1300 words! I admit I’m easily distracted, plus my mother had a small stroke last weekend and that threw me off course for a while. Research also forces me to adjust the narrative—Fox can’t wake at dawn and go hunting for breakfast when foxes are nocturnal creatures who largely eat at night. And if Fox has a jar on his head, how much would he really be able to see? Would living near humans enable him to identify musical instruments by sight or sound? I like animal stories and I’m not opposed to anthropomorphism, but I don’t want to strip these creatures of their wild nature.

I am ready to throttle the dog next door. Actually, I’d love to ask his owner why she thinks it’s ok to have a pet when she has absolutely no interest in meeting his needs. I’ve been working on “Fox & Crow” for a week now and I’m amazed it has taken me this long to write 1300 words! I admit I’m easily distracted, plus my mother had a small stroke last weekend and that threw me off course for a while. Research also forces me to adjust the narrative—Fox can’t wake at dawn and go hunting for breakfast when foxes are nocturnal creatures who largely eat at night. And if Fox has a jar on his head, how much would he really be able to see? Would living near humans enable him to identify musical instruments by sight or sound? I like animal stories and I’m not opposed to anthropomorphism, but I don’t want to strip these creatures of their wild nature.

Right now I’ve got the radio on and our new mayor is holding a press conference on the snowstorm. I thought a snow day would be the perfect occasion to stay in and write, but having a barking dog next door doesn’t help with concentration. I cornered one pet owner in the elevator before Xmas and explained that I worked at home and would appreciate it if she kept her dog away from the front door when she left for work. She replied that she worked at home, which literally knocked me back a step. How could ANYONE work with a little, yippy dog barking all day long?! She insisted that she always made sure her darling didn’t bark and bother others. “But she was barking all morning,” I countered. “Oh,” she replied. “I had to step out for a while.” Now that pet owner has dealt with her dog–I’ve hardly heard a peep out of it since that meeting in the elevator. But the woman next door to me works about 60 hours a week and her dog can’t stand being left alone. He whines when she leaves and then it escalates into full-blown barking. I’m more of a cat person, but I got to like dogs when I lived with my sister for six months in 1999. She had a big, black Lab crossed with a pit bull who used to terrorize passersby and would tear up her apartment every time she dared to leave him alone (which was every day). Then I moved in to write my first novel and Raf was instantly pacified. He didn’t want me to play with him all day or pet him constantly—he just didn’t want to be alone. PBS had a special on recently about the difference between cat lovers and dog lovers and I had to agree with the cat people: dog owners are selfish. They love to come home from work and have a dog jump up and lick their face, but they really don’t want to pay the

Right now I’ve got the radio on and our new mayor is holding a press conference on the snowstorm. I thought a snow day would be the perfect occasion to stay in and write, but having a barking dog next door doesn’t help with concentration. I cornered one pet owner in the elevator before Xmas and explained that I worked at home and would appreciate it if she kept her dog away from the front door when she left for work. She replied that she worked at home, which literally knocked me back a step. How could ANYONE work with a little, yippy dog barking all day long?! She insisted that she always made sure her darling didn’t bark and bother others. “But she was barking all morning,” I countered. “Oh,” she replied. “I had to step out for a while.” Now that pet owner has dealt with her dog–I’ve hardly heard a peep out of it since that meeting in the elevator. But the woman next door to me works about 60 hours a week and her dog can’t stand being left alone. He whines when she leaves and then it escalates into full-blown barking. I’m more of a cat person, but I got to like dogs when I lived with my sister for six months in 1999. She had a big, black Lab crossed with a pit bull who used to terrorize passersby and would tear up her apartment every time she dared to leave him alone (which was every day). Then I moved in to write my first novel and Raf was instantly pacified. He didn’t want me to play with him all day or pet him constantly—he just didn’t want to be alone. PBS had a special on recently about the difference between cat lovers and dog lovers and I had to agree with the cat people: dog owners are selfish. They love to come home from work and have a dog jump up and lick their face, but they really don’t want to pay the  price for that kind of loyalty. Hiring someone to walk your dog for twenty minutes doesn’t undo the loneliness some dogs experience when they’re left alone for 8-10 hours each day. Whereas cat owners understand that cats have a life of their own—they may greet you when you come home, but they’re just as likely to keep on doing what they were doing (sleeping). Cats aren’t needy. They aren’t loud. They aren’t desperate for attention. Cats are perfect for an apartment—most dogs are not. Cat owners don’t exploit their pet’s loyalty (in part because cats don’t practice loyalty). Writing this story has made me think about what the fox says in The Little Prince: “You become responsible forever for what you’ve tamed.” I would love to hold a giant bunny or cuddle with a fox, but you know what? That’s not what they’re for. That’s not what they want. And that matters. Ok, end of rant. Back to the story.

price for that kind of loyalty. Hiring someone to walk your dog for twenty minutes doesn’t undo the loneliness some dogs experience when they’re left alone for 8-10 hours each day. Whereas cat owners understand that cats have a life of their own—they may greet you when you come home, but they’re just as likely to keep on doing what they were doing (sleeping). Cats aren’t needy. They aren’t loud. They aren’t desperate for attention. Cats are perfect for an apartment—most dogs are not. Cat owners don’t exploit their pet’s loyalty (in part because cats don’t practice loyalty). Writing this story has made me think about what the fox says in The Little Prince: “You become responsible forever for what you’ve tamed.” I would love to hold a giant bunny or cuddle with a fox, but you know what? That’s not what they’re for. That’s not what they want. And that matters. Ok, end of rant. Back to the story.

January 1, 2014

Looking Back at 2013

December 30, 2013

Crow & Fox

I’m still thinking about the privileges I enjoy as a writer and after spending the weekend in Baltimore visiting illustrator Shadra Strickland, I realize how much I benefit from having so many committed artists as friends. We spent a lot of time catching up—and we ate at some fabulous restaurants—but we also had moments where Shadra went upstairs to her studio to draw and I settled on the couch to write my picture book story “Fox & Crow: A Christmas Tale.” It’s not a retelling of the classic fable but there is a trickster element and a moral, of course. It’s fascinating to see how other artists work—Shadra’s home is full of art, but her studio makes me feel like a kid in a candy store. I got to see an advance copy of her beautiful new book, Please, Louise, and paintings from her next book were pinned to a string like clothes on a line. As soon as I mentioned the fox in my story, Shadra pulled out books and cards and online illustrations that showed other artists’ interpretation of foxes in winter. My story was inspired by “Christmas in Yellowstone,” which I watch every year on PBS, and a video someone posted on Facebook of a crow who turned a plastic lid into a rooftop sled. I started writing the story before I left Brooklyn, but just a few hours with Shadra opened up a whole range of new possibilities. I’m hoping to finish the story before the new year begins; I met most of my goals for 2013 but didn’t manage to sell another picture book story. I already have 20 unpublished manuscripts so this will be #21. On Sunday afternoon we pulled out our journals and wrote new objectives for 2014; I definitely plan to self-publish another

I’m still thinking about the privileges I enjoy as a writer and after spending the weekend in Baltimore visiting illustrator Shadra Strickland, I realize how much I benefit from having so many committed artists as friends. We spent a lot of time catching up—and we ate at some fabulous restaurants—but we also had moments where Shadra went upstairs to her studio to draw and I settled on the couch to write my picture book story “Fox & Crow: A Christmas Tale.” It’s not a retelling of the classic fable but there is a trickster element and a moral, of course. It’s fascinating to see how other artists work—Shadra’s home is full of art, but her studio makes me feel like a kid in a candy store. I got to see an advance copy of her beautiful new book, Please, Louise, and paintings from her next book were pinned to a string like clothes on a line. As soon as I mentioned the fox in my story, Shadra pulled out books and cards and online illustrations that showed other artists’ interpretation of foxes in winter. My story was inspired by “Christmas in Yellowstone,” which I watch every year on PBS, and a video someone posted on Facebook of a crow who turned a plastic lid into a rooftop sled. I started writing the story before I left Brooklyn, but just a few hours with Shadra opened up a whole range of new possibilities. I’m hoping to finish the story before the new year begins; I met most of my goals for 2013 but didn’t manage to sell another picture book story. I already have 20 unpublished manuscripts so this will be #21. On Sunday afternoon we pulled out our journals and wrote new objectives for 2014; I definitely plan to self-publish another  novel in the coming year, but I don’t think I could do a picture book on my own. I could try to collaborate with a student artist or I could try sending my manuscript to editors outside the U.S. I suspect 2014 is going to force me to step outside my comfort zone…

novel in the coming year, but I don’t think I could do a picture book on my own. I could try to collaborate with a student artist or I could try sending my manuscript to editors outside the U.S. I suspect 2014 is going to force me to step outside my comfort zone…

The first time I visited Shadra’s studio in Brooklyn I headed home and passed out on the subway just as I reached my stop. I think my brain was overstimulated! And we did have to be careful we didn’t talk too much this weekend. Creatives need a lot of quiet time! As I always say, writing is 70% dreaming…

December 26, 2013

Boxing Day Deal!

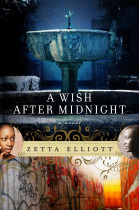

In Canada, the day after Xmas is when stores hold their biggest sales. We don’t observe Boxing Day here in the US, but Amazon is holding a sale on children’s and YA literature. A Wish After Midnight is one of the featured titles and the e-book is only $1 from now until January 31st! And the e-book of The Deep is 99 cents, too. If you’re looking for a great holiday read, now’s the time to stuff your stocking with e-books…

In Canada, the day after Xmas is when stores hold their biggest sales. We don’t observe Boxing Day here in the US, but Amazon is holding a sale on children’s and YA literature. A Wish After Midnight is one of the featured titles and the e-book is only $1 from now until January 31st! And the e-book of The Deep is 99 cents, too. If you’re looking for a great holiday read, now’s the time to stuff your stocking with e-books…

December 24, 2013

a long walk

Yesterday I turned in my last set of grades, handed out Xmas cookies to some people in my building, and then rushed downtown to see Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom. When Nelson Mandela passed away last month, I immediately thought of my Irish-Canadian grandfather and the way he used to save his copies of Maclean’s Magazine so that I could clip out articles for a school project on apartheid. High school wasn’t a happy time for me, but my senior year was memorable in part because I became “the” authority on apartheid in my mighty-white school. Like many “Black weirdos,” I had people in my family who felt I wasn’t “Black enough” and so did their best to undermine my self-esteem. I loved New Edition and Michael Jackson but I wasn’t into rap (unless you include The Beastie Boys) and I also listened to Duran Duran, Simply Red, and Depeche Mode. Occasionally my white peers would ask me about a rap group I’d never heard of, but mostly they accepted that I was just an “expert” on MLK and Mandela. I didn’t always attend school dances but when I did, the song most likely to get me out on the floor was “Sing Our Own Song” by UB40. The reggae song ends with a chant of “Amandla! Awethu!” My investment in the fight to free Mandela was, in a way, my only legitimate claim to Blackness—or so I thought.

Yesterday I turned in my last set of grades, handed out Xmas cookies to some people in my building, and then rushed downtown to see Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom. When Nelson Mandela passed away last month, I immediately thought of my Irish-Canadian grandfather and the way he used to save his copies of Maclean’s Magazine so that I could clip out articles for a school project on apartheid. High school wasn’t a happy time for me, but my senior year was memorable in part because I became “the” authority on apartheid in my mighty-white school. Like many “Black weirdos,” I had people in my family who felt I wasn’t “Black enough” and so did their best to undermine my self-esteem. I loved New Edition and Michael Jackson but I wasn’t into rap (unless you include The Beastie Boys) and I also listened to Duran Duran, Simply Red, and Depeche Mode. Occasionally my white peers would ask me about a rap group I’d never heard of, but mostly they accepted that I was just an “expert” on MLK and Mandela. I didn’t always attend school dances but when I did, the song most likely to get me out on the floor was “Sing Our Own Song” by UB40. The reggae song ends with a chant of “Amandla! Awethu!” My investment in the fight to free Mandela was, in a way, my only legitimate claim to Blackness—or so I thought.

As I left the theater yesterday, I realized that I stopped following Mandela’s journey after I graduated from high school. I don’t remember writing anything about South Africa in college, but I do recall writing a long op-ed for the campus paper about my disenchantment with King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. The college I chose to attend was even less diverse than my high school, and I knew I’d made a mistake almost as soon as I arrived. But I graduated with a determination to change course and a year later I was living in the US, taking classes in Black Studies at Brooklyn College. I volunteered with a youth collective and started tutoring kids in an after-school program in Fort Greene. I started paying closer attention to the tales my maternal grandmother used to share about our “Negro ancestors.” I realized that the door I’d been searching for—the elusive portal that would admit me to the world of Blackness—was for those with a commitment to social justice. It wasn’t about the music I liked or the clothes that I wore. I went natural that year and stopped perming my hair, but even that wasn’t as important as my growing awareness of the global struggle for Black liberation. And I realized yesterday that that was what Mandela did for me—the fight to end his imprisonment gave me a way to connect with something so much larger than myself and my sad little world where relatives teased me for having “cow lips” and “a white heart.” There’s no way to measure the impact Mandela had on the world, but I’m so, so grateful that his rise to power coincided with the start of my own search for a sense of purpose and belonging.

December 22, 2013

braveheart

Ed Spicer posted an article on my Facebook page earlier this week; the author encourages her fellow writers to “come clean” about the often unseen privileges that make their writing life possible. Well, it’s not easy being a black feminist writer but I do enjoy certain privileges that make it possible for me to put my work out into the world. I just finished watching Miss Potter (for the third time, I think); yesterday I went to see The Hobbit and after each film I had time to sit and reflect on what I’d just seen. All of that is possible because I’m a tenure-track professor. I complain a lot about my job but I do also thank the universe at least twice a day for giving me this life. I’m still marking papers—two sets of grades have been submitted and I am determined to submit the last set tonight. But when I’m slogging through student essays I often reward myself with favorite films and/or food. I’ve eaten a WHOLE lot of chocolate this week and will be very glad when all my Xmas cookies are delivered to their rightful recipients so I can stop popping one in my mouth every 3 hours. I eat a lot when I’m stressed out and December has been a pretty stressful month. Yet when Edith Campbell asked me to write a short essay about courage, I immediately knew what I wanted to say. She’s running a series about courage on her blog and my guest post is up today. Here’s some of what I had to say:

Ed Spicer posted an article on my Facebook page earlier this week; the author encourages her fellow writers to “come clean” about the often unseen privileges that make their writing life possible. Well, it’s not easy being a black feminist writer but I do enjoy certain privileges that make it possible for me to put my work out into the world. I just finished watching Miss Potter (for the third time, I think); yesterday I went to see The Hobbit and after each film I had time to sit and reflect on what I’d just seen. All of that is possible because I’m a tenure-track professor. I complain a lot about my job but I do also thank the universe at least twice a day for giving me this life. I’m still marking papers—two sets of grades have been submitted and I am determined to submit the last set tonight. But when I’m slogging through student essays I often reward myself with favorite films and/or food. I’ve eaten a WHOLE lot of chocolate this week and will be very glad when all my Xmas cookies are delivered to their rightful recipients so I can stop popping one in my mouth every 3 hours. I eat a lot when I’m stressed out and December has been a pretty stressful month. Yet when Edith Campbell asked me to write a short essay about courage, I immediately knew what I wanted to say. She’s running a series about courage on her blog and my guest post is up today. Here’s some of what I had to say:

Self-publishing does take courage—a recent opinion piece in The New York Times gave this wry definition of self-published authors: “Treated as Crazy Ranting People: either ignored or pitied by the general public until they do something that is brilliant or threatening.” Independent authors are often treated as pariahs—our books aren’t reviewed by the traditional outlets, won’t be considered for any major awards, and most bookstores won’t stock our titles. Publishers often look at indie authors as “tainted” and no longer viable, though there are exceptions to this rule.

The truth is, even people of color who KNOW the publishing game is rigged will look askance at a self-published book. To some Black writers (and readers), self-publishing is gutless, the most shameless surrender. “Just be patient,” they’ll say after you’ve faced a decade of disappointment. “Try harder!” they’ll exhort, as if the publishing industry were an actual meritocracy. Others assume there must be something lacking in your work but won’t read your book in order to dismiss or confirm that assumption.

So why self-publish? I explain my motivation in the acknowledgments section of THE DEEP:

I felt sure that there was a teenage girl somewhere in the world who needed this book yesterday. I never found anything like The Deep when I was scouring the shelves of my public library as a teenager, but it’s a story that might have changed my world—or at least my perception of myself. Black girls don’t often get to see themselves having magical powers and leading others on fabulous adventures.

G. Neri was Edi’s first guest. Be sure you follow her blog for the rest of this month to see what other authors have to say!

December 20, 2013

Plunge into THE DEEP for 99¢!

From now until Xmas you can get the Kindle edition of THE DEEP for 99 cents! I hope you’ll also consider giving a copy of the paperback to the teens in your life. I received this heartwarming letter from a 6th-grade student whose school I visited last week:

From now until Xmas you can get the Kindle edition of THE DEEP for 99 cents! I hope you’ll also consider giving a copy of the paperback to the teens in your life. I received this heartwarming letter from a 6th-grade student whose school I visited last week:

“Dear Ms. Elliott, I went to your presentation. It was fun. I like the idea of your book and I can’t tell you how much happiness I felt when I found out your characters are African American. After the presentation me and my friend kept talking about getting your books. A segestion: Bring more copyies of your books to sell because I would have bought it. Please come back next time.” Sincerly, Asante

I just learned that A Wish After Midnight is part of the 12 Days of Christmas promotion on Amazon.co.uk. So if you’re across the pond, you can get the e-book for £0.99! It’s also on sale in Germany for EUR 0,99!

Give books for the holidays!

December 18, 2013

“Black Girls Hunger for Heroes, 2″

Black feminists have a range of opinions (just ask one about Beyonce), and so it’s always invigorating to share ideas on the topics that matter most to me. Bitch Magazine‘s blog recently published a conversation I had with writer Ibi Zoboi about race and representation in The Hunger Games and YA speculative fiction. Our 45-minute talk amounted to over 5000 words and we had to reduce that to under 2000 words for the blog. We’ve decided to post the rest of our discussion here, and the full podcast will be available on the Bitch Magazine website in 2014.

Black feminists have a range of opinions (just ask one about Beyonce), and so it’s always invigorating to share ideas on the topics that matter most to me. Bitch Magazine‘s blog recently published a conversation I had with writer Ibi Zoboi about race and representation in The Hunger Games and YA speculative fiction. Our 45-minute talk amounted to over 5000 words and we had to reduce that to under 2000 words for the blog. We’ve decided to post the rest of our discussion here, and the full podcast will be available on the Bitch Magazine website in 2014.

Part II

IBI: My first contact with speculative fiction was the stories I would hear my family tell. They happened in Haiti—political stories intermingled with loogaroo stories, which is like a vampire-type figure in Haitian folklore. There was always a sense of magic and darkness and fear in those stories. There was always somebody who didn’t come home and it was usually associated with the tonton macoute (a bogeyman with a sack), or a loogaroo who came to get somebody’s child. I had two mystical, folkloric figures woven into these political stories about family and friends, so that line between what was real and what was not was never clear.

ZETTA: In my childhood, that line between fantasy and reality was very clear because I was reading British novels in Canada—C.S. Lewis and Frances Hodgson Burnett, which isn’t exactly fantasy. But her work featured these wealthy, white children living on the moors in England and was so far removed from my reality. And because those books didn’t serve as a mirror, fantasy was very much something that happened to other people. I didn’t really imagine magical, wonderful things happening to me because everything that I read said it only happened to kids of a certain color or a certain class. In terms of gender, at least girls were having adventures, too, so that was a good thing.

You and I are both writers and we’re obviously trying to generate our own stories. Is there a way for us to make an intervention in the field of YA fantasy? How do our stories reach our kids?

IBI: I’m seeing it play out on the institutional level. I have children in a diverse school and I see it played out on a very small scale. Not necessarily with the students, but with the parents. When it comes to decision making—like having an author come into the school—they’ll say, “We don’t know of any authors of color. Can you help us?” They have the luxury of not thinking about anything that exists outside of their own—

ZETTA: Bubble, essentially.

IBI: Yes. We cannot do that. If we do, it’s to our own detriment. In order for my children to be successful, they need what Melissa Harris-Parry calls “proximity to whiteness.” Which is one of the reasons I’m going to grad school—

ZETTA: In Vermont!

IBI: In Vermont! It’s not a conscious decision to be closer to whiteness, but I realize there are some skills that I may need to know.

ZETTA: And social connections.

IBI: It is about social connections. I’ve learned a lot. I’m going to school with editors. I can say, “Hey, what’s going on with this diversity thing?” And get an honest answer. “As your classmate, tell me what’s going on. Tell me the truth.” And I don’t think I’d have those kinds of relationships if I weren’t in grad school in Vermont.

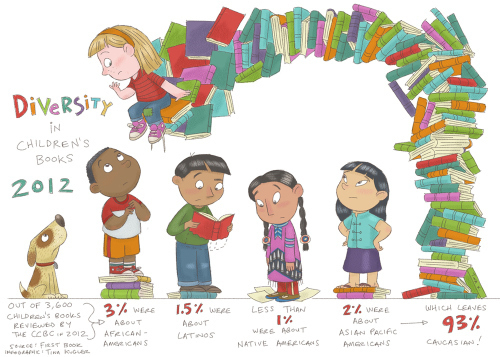

ZETTA: They’re lucky to have you, which brings me back to Tina Kugler’s illustration. That little white girl perched atop that stack of 93 books—it’s harmful to her because white children grow up thinking they’re the center of the universe. And that then makes it very hard for them to communicate cross-culturally because they haven’t had to have that experience, just as you were saying.

IBI: Very true. My daughter likes fantasy. She’s doing a report on Nnedi Okorafor’s Zahrah the Windseeker. She likes that book. To her it seems like there’s more diversity because of what I intentionally put in place around her.

ZETTA: You surround your kids with multicultural books.

IBI: So she doesn’t see a dearth because on our bookshelf there is abundance. I buy books that feature girls and boys of color. Already I set that foundation and they see me writing about kids of color. In terms of what we can do, I think it has to start at the ground level. I see it in the classroom. The teachers don’t know what books are out there. And if the teachers don’t know, the kids don’t know, their parents don’t know.

ZETTA: Librarians, too.

IBI: And on the other end of that, when I ask agents what’s going on they say, “We’re just not getting any submissions.” There’s a huge disconnect, and I wonder who is out there—besides the people we know—who else is trying to write?

ZETTA: That’s one of the reasons I chose to self-publish my latest novel. If we don’t take that route, if we’re afraid to self-publish, then what happens to all those other authors out there who haven’t had a book published but are desperate to see their work in a child’s hands? When I walk into a classroom as a black feminist writer, I know that I embody possibility. Kids looks at me and say “Wow—she’s one of us.” Or they come up to me and say, “You look like my cousin.” Or, “I have asthma, too!” They connect in a lot of ways.

ZETTA: That’s one of the reasons I chose to self-publish my latest novel. If we don’t take that route, if we’re afraid to self-publish, then what happens to all those other authors out there who haven’t had a book published but are desperate to see their work in a child’s hands? When I walk into a classroom as a black feminist writer, I know that I embody possibility. Kids looks at me and say “Wow—she’s one of us.” Or they come up to me and say, “You look like my cousin.” Or, “I have asthma, too!” They connect in a lot of ways.

So I feel like it’s important to me as an author who did the traditional route and the nontraditional route, to say, “You know what? I’m not waiting on the system any more because the game is rigged.” And I do encourage people to consider all their options: go the traditional route, wait and see if that works for you. But after ten years of waiting to get a book into print…I was done. I go into schools and I meet kids who need these books yesterday. They can’t wait another 3, 5, or 10 years. And there’s a long, black feminist tradition of self-publishing—Kitchen Table Press—all those scholars and writers and artists who didn’t want to have to wait.

IBI: I address that in my thesis. The Black Arts Movement started with writers self-publishing. I’m thinking on the other end, too, where I kind of want to call the gatekeepers to task. Not to say they have to do something—

ZETTA: They do!

IBI: Ok. They do, but at the same time there’s a lot of talk about diversity. When I do become serious about sending my work out, I want to document my process. “Ok, you say there needs to be diversity. Well, here I am. I just graduated—”

ZETTA: From a prestigious MFA program.

IBI: I’ve worked with some of the best people in the field and I’m submitting to publishers. Let’s see what happens.

ZETTA: I think there needs to be greater transparency.

IBI: I would want to have my process open to other aspiring authors. Because I don’t know what other people are going through. I’m one of two black women in my program and I’m getting an idea of what the different processes are. I’ll say, “Nobody gets six-figure advances any more.” And my white classmate will say, “ Uh, I did.” And I see that it’s possible.

ZETTA: It’s happening for some people.

IBI: Then I’ll talk to my black author friends and it’s a different story.

ZETTA: I think when we talk about what’s happening in our professional lives, that also can lead to greater accountability within the industry. Because there are all kinds of editors who pay lip service and say how desperately they want fantasy and speculative fiction from writers of color. Yet when I submit to them, I’ve been told my work is “unoriginal.” They make excuses. And I just think, when you have an advanced degree and you’ve won awards and you’ve gotten grants and you’ve published before—what really is stopping you from publishing in this market? And I have to say, I think it’s racism. And nobody really wants to talk about that. We need greater transparency and greater accountability: “I sent it to Agent X and she rejected it. Has Agent X taken on any writers of color?” For me, self-publishing is going to become more and more important. I’m open to publishing the traditional way, but I just have so much material and the demand in our community is so great, I don’t know that I have time to wait for the progress that may be on its way.

IBI: I don’t know. I want to see what lies ahead in terms of holding people accountable. I know from my program at VCFA there’s an agent who donated $5000 per year as a scholarship to have more diverse students come in. And that’s great, however—

ZETTA: However, you are already in the program. And once you graduate, are you going to get that six-figure deal? Are you going to have that contract? Are there going to be editors saying, “Ibi Zoboi! She’s won awards and grants, she’s traveled the world. Let’s see what she’s got.” You have how many manuscripts at this point?

IBI: Just three. A lot of people pay lip service to this idea of diversity. But I’m looking for that next author who is acclaimed, who’s winning awards, who’s got that much notoriety. In the UK, Malorie Blackman—

ZETTA: Who is the children’s literature laureate right now.

ZETTA: Who is the children’s literature laureate right now.

IBI: Right. She is the highest-paid Black entertainer in England. She’s the most highly respected.

ZETTA: And yet we have Walter Dean Myers. He’s the children’s laureate right now for the US. I feel like that’s part of the same system we have here in the US where we can have a black president and that increases diversity, but it doesn’t increase equity. What I’m looking for is for more people to have an equal opportunity. And the way the publishing industry is structured right now, that’s not going to happen.

IBI: I’m way more optimistic than you are. I see it happening with the new Common Core standards. Parents are speaking out, teachers are speaking out.

ZETTA: It’s going to take that kind of collective pressure because it can’t just be three authors of color who couldn’t place a manuscript saying, “There’s a problem with the publishing industry.” It’s going to take parents and teachers and librarians and kids saying, “This is what we want. We’re asking you, as an industry, to provide us with something we’re willing to consume.” I don’t understand how publishers can be walking away from that much money. Every other corporation is going after the Latino market and the Asian market and the African American market, and publishing just seems to be saying, “We really just don’t care. We have a guaranteed market with white readers and that’s what we’re going to go for—and we’re going to assume that white readers don’t want to read about people of color.”

ZETTA: It’s going to take that kind of collective pressure because it can’t just be three authors of color who couldn’t place a manuscript saying, “There’s a problem with the publishing industry.” It’s going to take parents and teachers and librarians and kids saying, “This is what we want. We’re asking you, as an industry, to provide us with something we’re willing to consume.” I don’t understand how publishers can be walking away from that much money. Every other corporation is going after the Latino market and the Asian market and the African American market, and publishing just seems to be saying, “We really just don’t care. We have a guaranteed market with white readers and that’s what we’re going to go for—and we’re going to assume that white readers don’t want to read about people of color.”

I do think it matters that we have narratives where girls are empowered and are leaders. I just taught After Earth, and I often think about Will and Jada Smith with their production company Overbrook. They decided to create projects that serve not only as vehicles for their kids’ talent, but that also produce the images we know are missing from society. I can just imagine what it means to Black boys to look up at the screen and see Jaden Smith in a spacesuit with two gigantic swords, vanquishing the alien. When have we ever seen a Black girl doing that?

IBI: That would take a movement. I think both the film industry and the publishing industry need to realize there is demand. I am a fan of Madea.

ZETTA: Oh no!

IBI: But it doesn’t have to be dumbed down in that way. You see how Divergent is coming to the big screen. The Mortal Instruments.

ZETTA: Beautiful Creatures was just on HBO the other day.

IBI: When is there going to be a girl of color in the lead role? We need a movement where a book becomes a movie and the whole country rallies around it.

ZETTA: But After Earth didn’t do well commercially. Are we going to be able to find an audience for that Black girl film? I don’t understand how young white kids can consume hip hop and watch Will Smith’s movies generally, but movies that are empowering to our kids don’t seem to get their support. When I think about those teenagers complaining about Rue or Beetee being played by Black actors, I have to wonder if white America—including the younger generations—is ready for a Black heroine.

IBI: It has to come from the bottom up. Like with hip hop. None of the artists was getting rich but they were ’hood rich. No one was thinking how to sell it to white suburban kids.

ZETTA: Big Hollywood studios are not the way to go, then, because they’re going to want that guaranteed profit.

IBI: For me, if I’m writing fantasy, I want to write about that Black Haitian girl from the ’hood in Brooklyn and really focus on my audience in Flatbush. And it’s what you’re doing, too. You’re focused on your immediate community. It’s what nonprofits call, “Local impact, global change.” Somehow there’s a ripple effect when your work is true, and honest, and really comes from the heart of a people. I didn’t see After Earth, so I don’t know how much it would resonate with the kid in Brooklyn who goes to the basketball court.

ZETTA: Your son would love it!

IBI: But there’s another element. I don’t know how to vocalize what I think. It has to capture the essence of what Black kids are going through today.

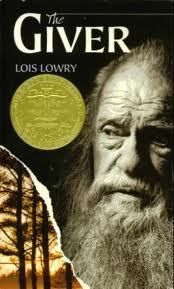

ZETTA: But that goes back to Rudine Sims Bishop’s idea about mirrors and windows. There are moments when a kid wants to open a book or go see a film and find a mirror—to see his or her community, and self, and family represented. I’ve gone into a special education classroom and seen Black and Latino kids reading The Giver by Lois Lowry. Fantastic book, but the cover has an old white man who looks like Santa Claus. And I just thought, “You can’t give that book to reluctant readers!” Then the teacher gave them my picture book Bird and they said, ‘That’s my world—brownstones! The park! He’s in Harlem on 125th!” They totally recognized the world of the book. But you also want them eventually to pick up a book like The Giver and say, “This isn’t a mirror, it isn’t showing me my world. But I’m looking into another world and I can find a place for myself there.”

ZETTA: But that goes back to Rudine Sims Bishop’s idea about mirrors and windows. There are moments when a kid wants to open a book or go see a film and find a mirror—to see his or her community, and self, and family represented. I’ve gone into a special education classroom and seen Black and Latino kids reading The Giver by Lois Lowry. Fantastic book, but the cover has an old white man who looks like Santa Claus. And I just thought, “You can’t give that book to reluctant readers!” Then the teacher gave them my picture book Bird and they said, ‘That’s my world—brownstones! The park! He’s in Harlem on 125th!” They totally recognized the world of the book. But you also want them eventually to pick up a book like The Giver and say, “This isn’t a mirror, it isn’t showing me my world. But I’m looking into another world and I can find a place for myself there.”

IBI: They have to be side by side. They need to see both options to make those literary connections.

ZETTA: We have a lot of work to do.

IBI: There’s a lot of work to do, and I’m glad people are already out there doing the work. I’m so thankful for Melissa Harris-Parry!

ZETTA: She making space for Black women’s voices to be heard.

IBI: I need our girls to know you can speak up for yourself and learn to think about the media critically.

December 17, 2013

Give books for the holidays!

I have a new essay up on The Huffington Post: “5 Things You Can Do to Promote Literacy over the Holidays.” I notice their editing team made some small changes but the message is clear—GIVE BOOKS! Here are a couple of suggested actions:

1. Give books as gifts!

All children need books that can serve as “mirrors and windows.” Books that reflect a child’s identity can boost self-esteem, and books about people who are different can teach a child to respect diversity. If your local bookstore doesn’t have what you want, ask them to order titles for you so they know there is demand for diverse books. You can also find dozens of multicultural titles at The Birthday Party Pledge.

2. Make room in your home for books.

Books are valuable, and should be treated with care. Assembling and decorating a bookcase can be a fun family activity. Whether your shelves are made of wood or milk crates, creating a place to grow your home library ensures that books will be treated with the respect they deserve. A bookcase also signals to visitors that books are a welcome gift in your home!

We’re also in the middle of updating the BPP site, so stay tuned for more great ideas and activities. Last night I was honored to attend the birthday celebration of Summit Academy Charter School. The student winners of their readathon were honored and the school presented the Red Hook library staff with a check for $1000! The library was closed after sustaining damage from Superstorm Sandy, and the students wanted to show their support. Heart-warming! As was the young man who came up right after my presentation and asked for a copy of Ship of Souls. Black and brown boys DO read. When I left the Crispus Attucks school yesterday morning, a 5th-grade student was reciting my summary of The Deep to the rest of his classmates. The librarian there sent me off with swag: a t-shirt, pen, and cap! More love…

We’re also in the middle of updating the BPP site, so stay tuned for more great ideas and activities. Last night I was honored to attend the birthday celebration of Summit Academy Charter School. The student winners of their readathon were honored and the school presented the Red Hook library staff with a check for $1000! The library was closed after sustaining damage from Superstorm Sandy, and the students wanted to show their support. Heart-warming! As was the young man who came up right after my presentation and asked for a copy of Ship of Souls. Black and brown boys DO read. When I left the Crispus Attucks school yesterday morning, a 5th-grade student was reciting my summary of The Deep to the rest of his classmates. The librarian there sent me off with swag: a t-shirt, pen, and cap! More love…

It’s snowing this morning. I have a 9am school visit and my first final exam is scheduled for this afternoon. No cancellations!