Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 44

August 8, 2015

free books!

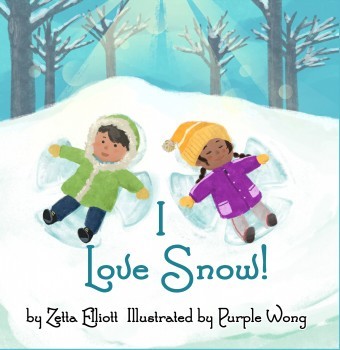

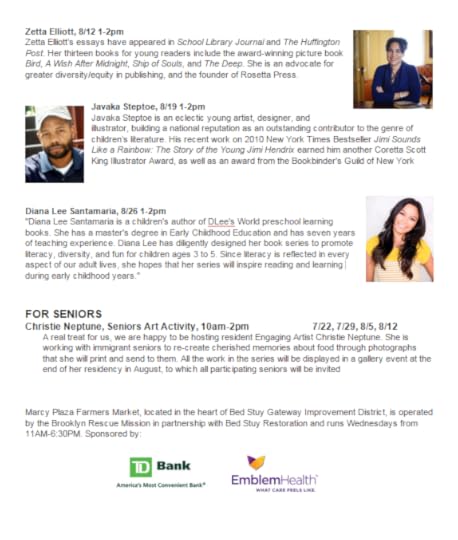

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000420_00047]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1439122770i/15797434.jpg) I’ve got two new titles and my designer has been working overtime to get the books ready for my upcoming reading in Bed-Stuy. 10 copies will be given away to the first children to attend the reading hour (1-2pm) at the Marcy Plaza Farmer’s Market on Wednesday. Hope to see you there!

I’ve got two new titles and my designer has been working overtime to get the books ready for my upcoming reading in Bed-Stuy. 10 copies will be given away to the first children to attend the reading hour (1-2pm) at the Marcy Plaza Farmer’s Market on Wednesday. Hope to see you there!

August 7, 2015

“Asian Pride” in Kid Lit

***

A confluence of events led me to write the prompt for Part 2. First, I had a frustrating and confusing experience with a very talented freelance illustrator in Hong Kong whom I hired for a picture book about winter in NYC. I specified in my job posting that I wanted illustrations of diverse kids done in the style of Ezra Jack Keats, and she did not disappoint. But when all the illustrations were completed, I pointed out that none of the children were Asian. I asked her to replace some of the white children but the revised illustrations showed no change. So I sent a few samples of US artists’ illustrations of Asian children but when the revised images arrived, there was still no change. I finally had to give her an ultimatum and she added three children to the book who were clearly Asian. When I went back through this artist’s portfolio, I realized that the children I had assumed were white might actually have been Asian according to her particular (or regional? cultural?) aesthetic.

A week later I saw this summary of Korean American comedian Margaret Cho’s appearance on Late Night with Seth Myers. In discussing the Black Lives Matter movement, Cho said:

“The hardest thing is, I am so down with all of the protests against police violence and police brutality — it’s something we’ve been dealing with,” she then explained. “It’s not just Eric Garner, it’s not just Baltimore; for me, it goes back to Amadou Diallo and Rodney King. But whenever white and black people fight, Asians and Mexicans don’t know what to do. Because we’re like, ‘Umm, are we white?’ We just want to be on the winning side.”

When I posted this quote from the interview on Facebook, a South Asian friend commented: “Which Asians is she talking about?” I was wondering the same thing! A few days later Ranier Maninding, who runs the provocative Facebook page The Love Life of an Asian Guy, argued that cultural appropriation is unacceptable except when it provides Asian Americans an alternative to assimilation into the dominant (white) culture:

When Asians immigrate to the United States they are given a choice: assimilate into American culture or continue doing things the traditional Asian way. One option will help you make friends while the other lands you in a pot of nasty Asian stereotypes.

“LOL! Ewww, what the hell are you eating for lunch? Is that dog? Why do you talk funny? CHING CHONG CHING CHONG! LOL CAN YOU EVEN SEE ME?!”

Get picked on or get along with the kids at school? OBVIOUSLY you’re gonna assimilate! The choice is clear but the next one isn’t. The next decision you have to make as an assimilating Asian is, “Should I assimilate with white communities or Black ones?” This decision is influenced by who you live near and what type of media you consume. Since most Asians immigrate to New York or California — areas with large Black communities — they inevitably side with Black folks.

“Are those really the only choices?” I wondered. And lastly, I saw this article, “ 7 Books about Growing Up Asian-American I Wish I’d Had as a Kid ,” and speculated that more like it will be published in ten, twenty, or even thirty years if so many Asian American kid lit creators continue to write outside their race. What do you think? Our 5 respondents once again share their opinions and offer us more food for thought…

***

Me: The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s helped to promote feelings of “Black pride” among African Americans; the distinct physical traits of African people were celebrated as Blacks throughout the diaspora resisted colonization by rejecting white beauty standards and assimilation into the dominant culture. Novels like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (in which a dark-skinned Black girl yearns for blue eyes) exposed the devastating effects of internalized racism, and popular singers like James Brown urged his fans to, “Say it loud–I’m Black and I’m proud!”

In the Black community here in the US, we have experience with and language for those who are white-identified: sellout, Uncle Tom, race traitor. Individuals who fail to display “loyalty to the race” can find themselves publicly shamed, though many African Americans continue to support Black celebrities who become thinner, blonder, and lighter as they “crossover” to the mainstream. Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novel American Born Chinese tackles issues of identity, shame, and belonging, yet as we saw in the

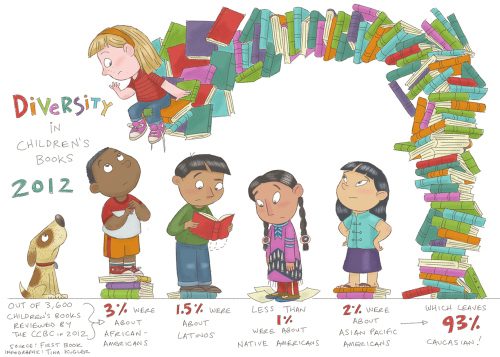

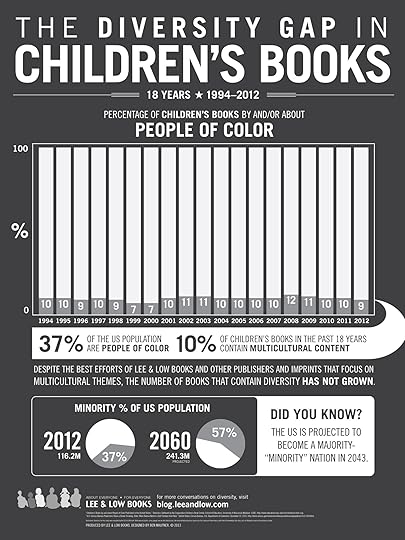

CCBC chart

, many Asian/Pacific American kid lit creators are still choosing to write outside their race.

In the Black community here in the US, we have experience with and language for those who are white-identified: sellout, Uncle Tom, race traitor. Individuals who fail to display “loyalty to the race” can find themselves publicly shamed, though many African Americans continue to support Black celebrities who become thinner, blonder, and lighter as they “crossover” to the mainstream. Gene Luen Yang’s graphic novel American Born Chinese tackles issues of identity, shame, and belonging, yet as we saw in the

CCBC chart

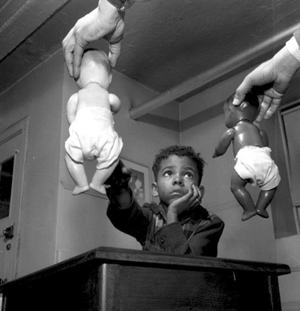

, many Asian/Pacific American kid lit creators are still choosing to write outside their race.What impact does this creative decision have on Asian American youth? If the Clarks’ famous “ doll test ” was recreated with Asian American instead of African American children, what results would you expect? Consider the aesthetic promoted by manga and anime, and the growing demand for eyelid surgery (“Westernization of the eyelid”) in Asia and the US. If Asian American youth find fewer “mirrors” in the children’s literature they consume, where do they learn to appreciate their own image? What role–if any–can kid lit creators play in promoting “Asian pride?” How would such a movement/message be received within your community?

***

Sandhya: As a child growing up in India and Ghana, the only South Asian characters I encountered in books and stories were mythological and historical ones. I don’t think I met characters who looked like me until I was well into my teens, and those were in adult novels!

Sandhya: As a child growing up in India and Ghana, the only South Asian characters I encountered in books and stories were mythological and historical ones. I don’t think I met characters who looked like me until I was well into my teens, and those were in adult novels!The lack of mirrors of myself in the kid lit I consumed impacted me in many and deep ways. Since most of the stories I read were about children with curly blonde hair and blue-eyes, those were the first characters that I created in my own first stories and well into my adolescent years. It never even occurred to me that children who looked like me could be the star attraction of a story. As a child, I would look at my hands and proudly notice that even though they were brown on the outside, they were creamy white on the inside; really, I wasn’t so different after all, was I?

It took a very long time for me to think of myself as beautiful or attractive; something I think about every single day as the mother of a 6 year old who is growing up in a drastically different, multicultural world. Brown is beautiful, I can say to her millions of times, but I realize that it’s not words that matter as much as my making sure that she regularly gets to encounter representations of herself in books, apps, movies, and TV shows.

Exactly ten years ago, I received a fellowship from the Asian American Writers Workshop to work on a literature research project. My task was to sift through—over a period of six months—middle grade and YA literature by and about Asian Americans and to make recommendations for pieces that could be included in the Elements of Literature textbooks anthologies that were being published by Holt, Rinehart, and Winston (now, Holt McDougal). This was 2005, a time when Asian American was typically synonymous with East Asian and where published kid lit South Asian characters and writers were few and far between. I remember ordering chapbooks, scouring the Internet, and sifting through anthologies for adults in search of pieces that would be appropriate for young audiences. It was quite the challenge.

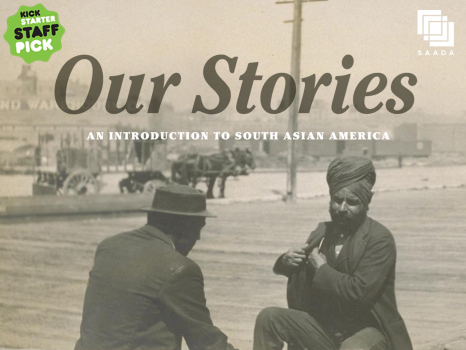

The landscape—and I am limiting myself to discussing characters of South Asian descent (Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, etc.)—is drastically different now, I am happy to report. Enormous strides were made in the last decade. The now defunct Parent’s Choice award-winning Kahani magazine launched many rising children’s authors and illustrators of South Asian descent. A wave of middle grade and young adult historical fiction set in India or the Indian disaspora brought strong female protagonists to life, and as the recent South Asian Book Award winners shows, kid lit has expanded to include non-historical characters as well. Another interesting trend is the number of independent publishing companies both here in the US and in South Asia such as Gnaana, Tara Books, Tullika, Little GuruSkool, and Bharat Babies formed to create books, apps, and games that speak to and represent the South Asian child and his or her cultural experience. I’ll be damned, but there is even a Kickstarter that recently funded the South Asian American Digital Archive’s (SAADA) Our Stories, a history textbook that will capture and share the stories of important South Asian Americans, many of whom exerted incredible influence over 130 years of American history, but who often went unnoticed and unrecorded in history books.

The landscape—and I am limiting myself to discussing characters of South Asian descent (Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, etc.)—is drastically different now, I am happy to report. Enormous strides were made in the last decade. The now defunct Parent’s Choice award-winning Kahani magazine launched many rising children’s authors and illustrators of South Asian descent. A wave of middle grade and young adult historical fiction set in India or the Indian disaspora brought strong female protagonists to life, and as the recent South Asian Book Award winners shows, kid lit has expanded to include non-historical characters as well. Another interesting trend is the number of independent publishing companies both here in the US and in South Asia such as Gnaana, Tara Books, Tullika, Little GuruSkool, and Bharat Babies formed to create books, apps, and games that speak to and represent the South Asian child and his or her cultural experience. I’ll be damned, but there is even a Kickstarter that recently funded the South Asian American Digital Archive’s (SAADA) Our Stories, a history textbook that will capture and share the stories of important South Asian Americans, many of whom exerted incredible influence over 130 years of American history, but who often went unnoticed and unrecorded in history books.

I am heartened.

And yet, I know that despite the fact that though there are more mirrors for South Asian children today, they remain mirrors that have to be sought after, are primarily created by independents and, at the end of the day, are subject to the BIG challenge of discoverability.

This is especially true for the world of children’s digital content where Jamie Naidoo and Sarah Park in their book Diversity Programming for Digital Youth point out that “a glance through the iTunes store reveals that most apps are created with a monocultural child in mind — the white, middle-‐class child. Essentially the “All-‐White World of Children’s Books” with the aid of digital enhancements has now morphed into the “All-‐White World of Children’s Apps.”

This is especially true for the world of children’s digital content where Jamie Naidoo and Sarah Park in their book Diversity Programming for Digital Youth point out that “a glance through the iTunes store reveals that most apps are created with a monocultural child in mind — the white, middle-‐class child. Essentially the “All-‐White World of Children’s Books” with the aid of digital enhancements has now morphed into the “All-‐White World of Children’s Apps.”

I think about this every single day and it is what has driven me to help co-found Diversity with Apps, an interdisciplinary coalition inspired by We Need Diverse Books. Our goal is to support the creation of diverse and inclusive children’s digital media products through research, best practices, and collaboration.

As someone rooted in the world of creating children’s content, I have the access and tools to find new and interesting things like Peter Gould’s series of apps for Muslim kids or Storied Myth’s diverse cast of characters that include Luv and Kush, clearly South Asian kids. But what about the parent who is so busy with work and school paperwork and for whom downloading an app or picking up a library book is just about selecting from what’s on display or featured? What happens to those children? They fall into the valley of blonde-haired, blue-eyed, peach-color crayons—and it is up to us as creators, editors, distributors, and reviewers of children’s content to make sure that they have a way out.

Sandhya Nankani is founder of Literary Safari , a literacy company committed to creating inclusive children’s content apps that celebrate storytelling while supporting 21st century skills such as problem solving, creativity, and social- ‐ emotional learning.

***

Sarah: If the Clarks’ doll test was recreated with Asian Americans, I believe the results would be similar – we would choose dolls with bigger eyes and lighter skin. We don’t need to replicate the test; the amount of money Koreans and Korean Americans pour into cosmetic surgery, skin lightening creams, etc., speaks for itself.

Sarah: If the Clarks’ doll test was recreated with Asian Americans, I believe the results would be similar – we would choose dolls with bigger eyes and lighter skin. We don’t need to replicate the test; the amount of money Koreans and Korean Americans pour into cosmetic surgery, skin lightening creams, etc., speaks for itself.

We are told through media that we are not beautiful, and that our value and usefulness are determined by our sexual attractiveness to those who wish to consume our bodies (see “Problematic Representations of Asian American Gender and Sexuality,” chapter 04, in Kent Ono and Vincent Pham’s Asian Americans and the Media). When I was in graduate school, The Last Samurai movie was about to premiere near campus, so someone from the studios sent out a request to UCLA students for “beautiful Asian women” who would dress in ancient Japanese garb and mingle at the premiere’s after party. This is what Hollywood wants us to do: be beautiful, be a prop, be the quiet, submissive subject of the white man’s gaze. So if Hollywood has an ambivalent and controlling relationship with Asian American beauty, it is no wonder that young adult literature is beginning to address Asian American body image issues. The double  eyelid surgery – a popular surgery where a cut in the skin creates a fold in the double eyelid – is a major plot point in both An Na’s The Fold and Laura Williams’ Slant (though Slant uses problematic language and I found it to be a less satisfying read). Through these books, young readers can learn about the surgery.

eyelid surgery – a popular surgery where a cut in the skin creates a fold in the double eyelid – is a major plot point in both An Na’s The Fold and Laura Williams’ Slant (though Slant uses problematic language and I found it to be a less satisfying read). Through these books, young readers can learn about the surgery.

But readers learn about it, and then what? Do they conclude that Korean women are shallow? Korean women’s obsession with western beauty did not emerge in a vacuum, nor does it thrive in one. In her dissertation, Sharon Heijin Lee ‘[locates] the Korean beauty aesthetics within a genealogy of imperial racial formation,” mapping how the seemingly discrete spheres of “popular and consumer culture, medicine, tourism, the military and other governmental institutions” actually work together in a racial project (see Michael Omi and Howard Winant’s Racial Formations in the United States) to convince Korean women – and men, in their policing of the female body – that western features are more desirable (“The (Geo)Politics of Beauty: Race, Transnationalism, and Neoliberalism in South Korean Beauty Culture,” 2012). And while books such as The Fold and Slant can combat the barrage of messages that rounder eyes are more beautiful, are two books on a single topic enough? No, of course not. Asian Americans – and all readers – need a variety of stories in order for the diversity of our experiences to be better understood. As well, at least in terms of body image, there is more than just the issue of double eyelids. Asian Americans – both male and female and other – struggle with weight, with skin, and with other features, similar to many other youth. We need more books that celebrate and affirm Asian beauty, as well as more books that depict the range of image issues we continue to struggle with. Asian American authors and illustrators – people who experience these struggles themselves – are well poised to address these issues.

I’m not looking forward to the time when my daughter will start worrying that she is not as beautiful as her white friends or the white children she sees in the media. My husband and I are working hard to proactively counteract negative messages by emphasizing Korean culture and aesthetics, buying Asian-looking dolls, and reading Korean and Asian American picture books at home, but we have limited options compared to white parents seeking mirrors for their children. And my daughter has an advantage because her mother is an Asian American children’s literature scholar, but what about the Asian American youth whose parents don’t know of Asian American children’s books, or why it’s so important for Asian Americans to see healthy and accurate images of themselves in the world around them? When I give gifts to my friends’ children, I usually gift Asian American children’s literature, but I have to plan ahead because I can’t walk into any Barnes & Noble and find, for example, New Clothes for New Year’s Day (Hyun-Joo Bae). So there’s an additional barrier to accessing Asian American stories and images.

I’m not looking forward to the time when my daughter will start worrying that she is not as beautiful as her white friends or the white children she sees in the media. My husband and I are working hard to proactively counteract negative messages by emphasizing Korean culture and aesthetics, buying Asian-looking dolls, and reading Korean and Asian American picture books at home, but we have limited options compared to white parents seeking mirrors for their children. And my daughter has an advantage because her mother is an Asian American children’s literature scholar, but what about the Asian American youth whose parents don’t know of Asian American children’s books, or why it’s so important for Asian Americans to see healthy and accurate images of themselves in the world around them? When I give gifts to my friends’ children, I usually gift Asian American children’s literature, but I have to plan ahead because I can’t walk into any Barnes & Noble and find, for example, New Clothes for New Year’s Day (Hyun-Joo Bae). So there’s an additional barrier to accessing Asian American stories and images.

And the thing is, so much of this is internalized that I still have to check myself. When my daughter was born, people commented that it was likely that she’d have double eyelids, like her father (who is also Korean), and I was so pleased. But she is beautiful whether her eyes are big or small, whether they are like mine or her father’s. When she grows up and reads this, she’s going to know that her mother wanted her to inherit her father’s eyes, and she’s going to learn that even her mother suffers from body image issues, but she will also learn that her mother is trying to be conscious and proactive and affirming.

And the thing is, so much of this is internalized that I still have to check myself. When my daughter was born, people commented that it was likely that she’d have double eyelids, like her father (who is also Korean), and I was so pleased. But she is beautiful whether her eyes are big or small, whether they are like mine or her father’s. When she grows up and reads this, she’s going to know that her mother wanted her to inherit her father’s eyes, and she’s going to learn that even her mother suffers from body image issues, but she will also learn that her mother is trying to be conscious and proactive and affirming.

We need more diverse books depicting Asian Americans of all body types and experiences so that our children – both Asian American and non-Asian American – can learn about authentic and beautiful Asian American aesthetics. Personally, I think there is much beauty in Korean culture and aesthetics. I was excited to wear my Korean hanbok (traditional dress) with my baby girl for her first birthday party (see photo), and I hope that when she grows up, she’ll see the Korean culture around her and find it as beautiful as I do. I hope that more people will be exposed to Korean culture so that they too will appreciate and respect – and not exploit – our bodies and our stories. I hope Asian American writers and artists will take the lead in this very important and transformational racial project.

Sarah Park Dahlen is an assistant professor in the Master of Library and Information Science Program at St. Catherine University.

***

Janine: These are all excellent questions. You could write books (many!) on this topic alone. As a woman of Chinese, African American, white, and Native descent whose day job has been working in the social justice movement for nearly 15 years, I can’t help but connect these questions to the visibility/invisibility of Asian/Pacific Islanders in the Movement. From the stereotypes and common portrayals of history, you might not think that Asian/Pacific Islander Americans played or play much of a role as activists. And yet the more attention we pay, the more we’ll find. Yuri Kochiyama stood beside Malcolm, Grace Lee Boggs fought for worker and tenants rights in New York and Detroit, and Philip vera Cruz was a co-founder of United Farm Workers Union and an integral organizer alongside Caesar Chavez.

Janine: These are all excellent questions. You could write books (many!) on this topic alone. As a woman of Chinese, African American, white, and Native descent whose day job has been working in the social justice movement for nearly 15 years, I can’t help but connect these questions to the visibility/invisibility of Asian/Pacific Islanders in the Movement. From the stereotypes and common portrayals of history, you might not think that Asian/Pacific Islander Americans played or play much of a role as activists. And yet the more attention we pay, the more we’ll find. Yuri Kochiyama stood beside Malcolm, Grace Lee Boggs fought for worker and tenants rights in New York and Detroit, and Philip vera Cruz was a co-founder of United Farm Workers Union and an integral organizer alongside Caesar Chavez. These individuals are not isolated instances or anomalies. The San Francisco Bay Area has been home to sizeable API communities for over 100 years, and a region for API activism for just as long. I have friends whose parents were active in the Civil Rights Movement, and bore the brunt of the violence at San Francisco State University to carve out the first Ethnic Studies program in the nation. (UC Berkeley protests got all the visibility, but far more police violence was committed against working class students at SF State.)

And in my work in the social justice movement today, some of the fiercest champions, activists, and organizers I know are Asian/Pacific Americans. I don’t know what it is, perhaps a deferral of the spotlight. Perhaps dominant stereotypes and invisibility make APIs less appealing to the media. Perhaps mainstream thought refuses to recognize the oppression APIs have historically experienced. Maybe APIs would rather forget, and turn away from histories of oppression.

Sadly, many are still bought into the dream that assimilation can overcome racism, poverty and lack of opportunity. Unfortunately this is an individualistic view (mythology) that fails to raise all ships, boats, rafts. Artist-activist friends at Dignidad Rebelde remind us of Fred Hampton’s words: Fight Racism with Solidarity.

Individualism stemming from assimilation mentality isn’t solidarity. Assimilation mythology is a form of genocide.

I know that not all Asian/Pacific Islander writers choose to write about white s/heroes. Sadly it appears that these are the writers that are disproportionately published.

I hope that more API writers and creators have the opportunity to know their roots and deepen their community ties. (Especially when we’re minorities in a homogenous environment, this is no easy task, and demands perseverance and conscious re-education.) And I hope that those who already embrace themselves have more and more opportunities to share their stories and make us less invisible.

Our histories, our identities, our future generations are on the line.

Janine Macbeth is the founder of Blood Orange Press , a sprouting children’s publishing company dedicated to correcting the invisibility of people of color in children’s literature. @BloodOrangePres

***

Mike: When I was a teenager I didn’t give any thought to having a future in writing – my dream was to become a comic book illustrator. That dream went by the wayside for a number of reasons, not the least of which was my family’s generation-spanning opposition to anyone in MY generation becoming an artist of any kind, but in high school I still spent a lot of time drawing, either characters of my own making, or classic Marvel and DC Comics characters. One of my favorites was a character that’ll soon have his own show on Netflix: Iron Fist, who is, of course, very much a white savior character. And as usual, I didn’t give that aspect of the character any thought at all until a year and a half ago, when I started engaging in public dialogue about diversity. I uncritically mentioned Iron Fist in blog interviews when my first book came out, in fact.

Mike: When I was a teenager I didn’t give any thought to having a future in writing – my dream was to become a comic book illustrator. That dream went by the wayside for a number of reasons, not the least of which was my family’s generation-spanning opposition to anyone in MY generation becoming an artist of any kind, but in high school I still spent a lot of time drawing, either characters of my own making, or classic Marvel and DC Comics characters. One of my favorites was a character that’ll soon have his own show on Netflix: Iron Fist, who is, of course, very much a white savior character. And as usual, I didn’t give that aspect of the character any thought at all until a year and a half ago, when I started engaging in public dialogue about diversity. I uncritically mentioned Iron Fist in blog interviews when my first book came out, in fact.

It was therefore revelatory to read Gene Luen Yang’s masterpiece American Born Chinese. It was like nothing I’d ever read before, and the illustrations brought the story’s psychological impact home in a way I didn’t expect. The final panels of the book…I recognized what was happening in those panels, through personal experience, because I am still white-identified. I can’t dispute that fact. The phrase that’s often used in that context is “yellow on the outside, white on the inside,” and that certainly is apt on physiological and psychological terms, but I tend to picture the opposite, in more metaphorical terms: yellow on the inside – an increasingly pale, atrophied, alienated identity as an Asian-American – and white on the outside. Painted white, perhaps; whitewashed; coated in layers upon layers of whiteness.

Part of the brilliance of American Born Chinese is how it portrays that layering of whiteness, a process that I engaged in, and am only now trying to reverse. I’m not doing it well; I’m not doing it effectively; I’m still called a banana Asian now and again, and I’m unable to counter such comments. My involvement in diversity work, which still feels brand new to me, has agitated my biggest, loudest, harshest inner demons, and they are reopening old gashes in my psyche with a vengeance.

Part of the brilliance of American Born Chinese is how it portrays that layering of whiteness, a process that I engaged in, and am only now trying to reverse. I’m not doing it well; I’m not doing it effectively; I’m still called a banana Asian now and again, and I’m unable to counter such comments. My involvement in diversity work, which still feels brand new to me, has agitated my biggest, loudest, harshest inner demons, and they are reopening old gashes in my psyche with a vengeance.

I often wonder what it would have been like to read American Born Chinese when I was in my teens, instead of in my thirties. Would I have been more conscious about the ways in which my identity was being warped, and the ways in which I allowed it to happen? Would it have helped me become less white-identified than I am today? Maybe my lifetime tally of self-hatred would be lower than it’s been over the years. Maybe not; I was not the most emotionally evolved teenager the world has ever seen. But maybe.

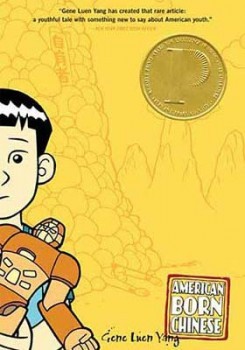

Then there’s my daughter. She and I are eerily alike in some ways. She’s going to face some of the same challenges I faced in my youth, and I struggle to keep from infecting her with my own fears of those challenges. She’s very different from me in other ways, however. She’s stronger in some ways, and more self-aware. She’s read both of my books, the published one and the soon-to-be-published one, and she strongly identifies with them both. Recently her summer camp had a so-called “Superhero Friday,” and my daughter chose to go as Polly Winnicott-Lee, one of the two most important characters in Geeks, Girls, and Secret Identities, and she made that choice because in her words she both is like Polly and looks like Polly. I was powerfully struck by that, because Geeks is an illustrated novel.

Maybe the illustrations weren’t a deciding factor, but I think they were. It’s possible, maybe even probable, that I’ve already visited my own issues with cultural alienation upon my daughter; perhaps my ongoing identity disentanglement is one of the more dismal ways in which she and I will turn out to be alike. I feel hopeful, though, and it means something that this particular feeling of hope is rooted in my daughter’s interaction with a book that I wrote and includes pictures of explicitly mixed-race characters. I can describe that feeling of hope in another way, too: I hope present and future readers of Asian descent will have experiences less like mine, and more like my daughter’s, at least in this one instance. We can hope. Right?

Maybe the illustrations weren’t a deciding factor, but I think they were. It’s possible, maybe even probable, that I’ve already visited my own issues with cultural alienation upon my daughter; perhaps my ongoing identity disentanglement is one of the more dismal ways in which she and I will turn out to be alike. I feel hopeful, though, and it means something that this particular feeling of hope is rooted in my daughter’s interaction with a book that I wrote and includes pictures of explicitly mixed-race characters. I can describe that feeling of hope in another way, too: I hope present and future readers of Asian descent will have experiences less like mine, and more like my daughter’s, at least in this one instance. We can hope. Right?

Mike Jung is the author of the middle-grade novels Geeks, Girls, and Secret Identities (Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic, 2012) and Unidentified Suburban Object (Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic, 2016). He’s also contributed essays to the anthologies Dear Teen Me (Zest, 2012), Break These Rules (Chicago Review Press, 2013), and 59 Reasons to Write (Stenhouse, 2015). Mike is a founding member of the We Need Diverse Books team, and serves as a grant officer for the WNDB Internship Program.

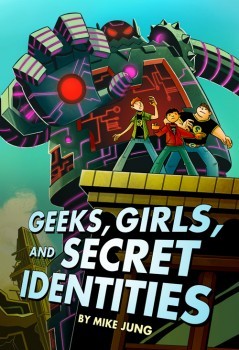

Sona: The first time I saw someone who looked like me in a book, I was 19 and in college. I had this vague idea in my head by then of wanting to be a writer, but it was sort of like a fantasy — brown girls don’t write books. Or they didn’t, until then. The book was Ameena Meer’s Bombay Talkie, about a knee-high generation Muslim teen. Her experience was like mine in many ways, but also so completely different. Still, I latched onto her wholeheartedly. And when the author came to Rutgers for a signing, I was the first in line. I shyly told her about my writerly ambitions, and she told me that if she could do it, so could I.

Sona: The first time I saw someone who looked like me in a book, I was 19 and in college. I had this vague idea in my head by then of wanting to be a writer, but it was sort of like a fantasy — brown girls don’t write books. Or they didn’t, until then. The book was Ameena Meer’s Bombay Talkie, about a knee-high generation Muslim teen. Her experience was like mine in many ways, but also so completely different. Still, I latched onto her wholeheartedly. And when the author came to Rutgers for a signing, I was the first in line. I shyly told her about my writerly ambitions, and she told me that if she could do it, so could I.

I’d had other people tell me that I should write before then. But until that moment, I didn’t take it seriously. I couldn’t. It took seeing her do it to give me the strength, the courage. But I got lucky with that book and that meeting. There are so many kids of Asian descent who still rarely see themselves in books — let alone writing books. “Writer” is sadly not in the top ten (or top 100) career choices for many kids from marginalized communities, Asian or otherwise. And even when we do see ourselves on the page, the representations — so frequently created by those not from within these communities — are often troublesome.

We’ve also heard by now Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s idea of “ the danger of a single story .” I think that holds more true today than ever. We’re repeating tropes and long-held stereotypes, reaffirming those ideas for future generations. They’re so ingrained, we don’t even know that we can step outside of them. We need to take control of the images being created — and the only way to do that is to become part of the process. Become writers, artists, editors, publishers, booksellers.

The struggle here is twofold, I think. One is to be brave enough to think of ourselves as heroes (or antiheroes), protagonists, characters with agency and power. The second is to put ourselves in places we’re not expected. Not every Asian story has to be about the immigrant experience or struggling with two cultures. We can be the rebel leaders in that deep space opera. The drivers in that summer road trip romp. Front and center in that fierce basketball drama. And the romantic lead in that impossible love story. We need to be more than just the warriors or mathletes or spelling bee competition. We need to be able to reimagine ourselves on the page in new scenarios and take control of the images we’re creating. Only then can we shift the narrative and reshape it.

The struggle here is twofold, I think. One is to be brave enough to think of ourselves as heroes (or antiheroes), protagonists, characters with agency and power. The second is to put ourselves in places we’re not expected. Not every Asian story has to be about the immigrant experience or struggling with two cultures. We can be the rebel leaders in that deep space opera. The drivers in that summer road trip romp. Front and center in that fierce basketball drama. And the romantic lead in that impossible love story. We need to be more than just the warriors or mathletes or spelling bee competition. We need to be able to reimagine ourselves on the page in new scenarios and take control of the images we’re creating. Only then can we shift the narrative and reshape it.Sona Charaipotra is co-founder of CAKE Literary and co-author of Tiny Pretty Things (HarperTeen, 2015). She is also a full-time freelance writer focusing on entertainment, lifestyle and parenting.

Protected: “Asian Pride” in Kid Lit

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

August 1, 2015

first step

Pandora is playing the most random assortment of songs this afternoon: Nina Simone, Michael Jackson, Rihanna, WHAM!, Sia, Adele, Big Mama Thornton. Earlier today I went for a run and the carousel in Prospect Park was playing the theme song from Dr. Zhivago—followed by a song I’m sure is by Boney M! Normally I do what I have to do without music in the background; I don’t run with music and can get distracted with too many singalongs if I write with Pandora on. But I am testing my mettle these days. Last week I started a fast that involves abstaining from cake, cookies, and pie—no junk food or fast food for 21 days. We’re in the middle of a heat wave and I’m not allowed to have ice cream. Today I went into Duane Reade and my favorite brand of kettle corn was on sale but I couldn’t buy a bag. I had to pass Chipotle without going inside, and I’ve been at the grocery store a LOT because I can no longer just pick something up for dinner on my way home. I miss chocolate more than I thought I would, but I’m not giving up sugar entirely; I can have fruit and I’m still eating mini-wheats for breakfast. I suspect that by the time I reach the end of that 21st day, I’m just going to binge on all the things I’ve denied myself for the past 3 weeks. But I want to believe I can do this. Just like I want to believe—have to believe—that I can finish this novel by the end of August. It’s a new month; my horoscope says this will be the best month of my professional life, so I’m going for it while the stars are aligned in my favor.

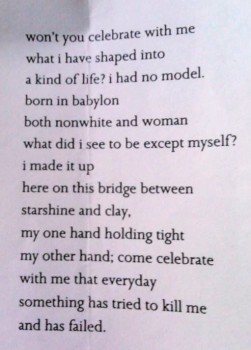

Pandora is playing the most random assortment of songs this afternoon: Nina Simone, Michael Jackson, Rihanna, WHAM!, Sia, Adele, Big Mama Thornton. Earlier today I went for a run and the carousel in Prospect Park was playing the theme song from Dr. Zhivago—followed by a song I’m sure is by Boney M! Normally I do what I have to do without music in the background; I don’t run with music and can get distracted with too many singalongs if I write with Pandora on. But I am testing my mettle these days. Last week I started a fast that involves abstaining from cake, cookies, and pie—no junk food or fast food for 21 days. We’re in the middle of a heat wave and I’m not allowed to have ice cream. Today I went into Duane Reade and my favorite brand of kettle corn was on sale but I couldn’t buy a bag. I had to pass Chipotle without going inside, and I’ve been at the grocery store a LOT because I can no longer just pick something up for dinner on my way home. I miss chocolate more than I thought I would, but I’m not giving up sugar entirely; I can have fruit and I’m still eating mini-wheats for breakfast. I suspect that by the time I reach the end of that 21st day, I’m just going to binge on all the things I’ve denied myself for the past 3 weeks. But I want to believe I can do this. Just like I want to believe—have to believe—that I can finish this novel by the end of August. It’s a new month; my horoscope says this will be the best month of my professional life, so I’m going for it while the stars are aligned in my favor.  Today I mailed some books to a deserving teacher and then came home to chicken and brown rice with raspberries for dessert (sigh). Then I made myself open the file that contains the novel I started back in 2003. I also pulled up the outline but then remembered I had a printed copy somewhere. That led me to unpack the tray that sits on my ottoman and collects all the loose papers that would otherwise clutter my desk. I found a giant folder from 2003, then another with notes and articles and photographs from the last time I worked seriously on this historical novel, which was 2013. Mixed in were notes for The Deep and other projects I’ve started and finished over the past decade. But I finally found my outline; it says out of 51 planned chapters, I’ve got 41 done, 8 partially done, and 2 I haven’t started at all. So that’s what I’ll be doing for the next 30 days. Mixed in with all the novel-related crap was this poem by Lucille Clifton, which really resonated with me today—as it must have when I “filed” it in the tray years ago. Like so many Black women artists, I have shaped my dreams and talents and limited resources into “a kind of life.” And I’ve been knocked down a few times, but I haven’t been defeated yet…

Today I mailed some books to a deserving teacher and then came home to chicken and brown rice with raspberries for dessert (sigh). Then I made myself open the file that contains the novel I started back in 2003. I also pulled up the outline but then remembered I had a printed copy somewhere. That led me to unpack the tray that sits on my ottoman and collects all the loose papers that would otherwise clutter my desk. I found a giant folder from 2003, then another with notes and articles and photographs from the last time I worked seriously on this historical novel, which was 2013. Mixed in were notes for The Deep and other projects I’ve started and finished over the past decade. But I finally found my outline; it says out of 51 planned chapters, I’ve got 41 done, 8 partially done, and 2 I haven’t started at all. So that’s what I’ll be doing for the next 30 days. Mixed in with all the novel-related crap was this poem by Lucille Clifton, which really resonated with me today—as it must have when I “filed” it in the tray years ago. Like so many Black women artists, I have shaped my dreams and talents and limited resources into “a kind of life.” And I’ve been knocked down a few times, but I haven’t been defeated yet…

July 31, 2015

A Wave Came Through Our Window

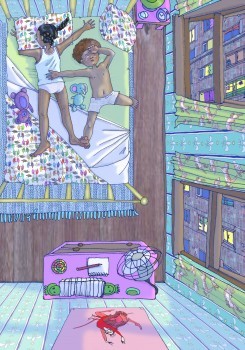

This morning I received the greatest gift—13 stunning illustrations by Charity Russell for my forthcoming picture book. I thought I’d share a few pages to whet your appetite:

Last night a wave came through our window.

Not a splashing, salty wave.

Not a greedy, hungry wave that tugs at your ankles as you run up the beach.

It was a different kind of wave…

In the summer, we sleep with the windows open WIDE.

It gets real hot in our apartment, so Benny and I sleep in our underwear.

Papa tells us to lie still, but hot nights make you feel itchy inside.

Benny and I toss and turn.

We kick off the sheets and slide our hands under our pillows

’cause that’s where the cool is at.

The air in our bedroom feels warm and thick like Grandma’s split pea soup.

The fan on our dresser turns and churns the air but doesn’t cool the room at all.

Benny and I hold our hands up high and wait for the first wave to come through our window.

Sometimes it comes right away. Sometimes we have to wait.

I spread my fingers wide apart and look out at the moon.

It is bright and round like a big white zero in the middle of the dark blue sky.

Benny’s arms aren’t as strong as mine.

She gets tired of waiting and starts to whine. “When’s the wave going to come?”

“Shhh,” I tell her. “It’s coming now. I can feel it.”

July 30, 2015

hope & a token

My friend Stefanie once said, “Hope and a token will get you on the train.” She denies it now, but I continue to attribute this pearl of wisdom to her because her people are from down south and it’s the kind of folk wisdom her grandmother might have passed along. I come back to it again and again because hope has its place in our lives, but ultimately it takes action to make things happen. I’m not going to stand outside the turnstiles with my fingers crossed, nor am I going to beg a swipe from another commuter. I have thirteen unpublished picture book manuscripts and I realized recently that I cannot publish all of them on my own. So what’s a girl to do? Well, last week I looked up agents who say they’re seeking diverse picture books and sent out a few queries. But agents can take forever to respond—if they respond at all—so I also reached out to a few editors. I’m not optimistic because I’ve been down this path before, but there’s no point in NOT trying. We need multiple strategies to tackle the lack of diversity in children’s publishing, and I will need help if I want to clear this backlog of manuscripts. I could self-publish the autism picture book story I wrote last weekend, Benny Doesn’t Like to Be Hugged, or I could take a couple of months and see if any presses are interested. Patience isn’t a strength of mine, but persistence is…

Last weekend I met a friend uptown to see the Classical Theater of Harlem’s production of The Tempest. It was magical! So well done, and it was actually fun to block out the regular noises of the city in order to focus on the actors’ words. I attended a high school in Toronto where students were required to read a Shakespeare play every year. Then we’d get on buses and trek up to Stratford, Ontario to attend the Shakespeare festival held at the Globe. The play we saw almost never corresponded with the play we studied, but I guess it was still “a positive cultural experience.” When I was in college, I spent a semester abroad in England; as soon as I arrived, I was urged to go into town to see a production of The Tempest that was being held in Arundel Castle. That was the first time I saw Black actors performing Shakespeare! Caliban was Black, of course, but so was the prince Ferdinand (Miranda was white). That semester abroad didn’t live up to its auspicious beginning, and I haven’t really bothered with Shakespeare since then. But I really wanted to see this Harlem production with its incorporation of accents and actors from throughout the African diaspora. Ariel was probably my favorite—she sang and howled and enchanted the shipwrecked sailors, sometimes while suspended above the stage. And Prospero was fantastic, too. Not the ideal father but he understood that sometimes you have to trouble the water to get things done…

Last weekend I met a friend uptown to see the Classical Theater of Harlem’s production of The Tempest. It was magical! So well done, and it was actually fun to block out the regular noises of the city in order to focus on the actors’ words. I attended a high school in Toronto where students were required to read a Shakespeare play every year. Then we’d get on buses and trek up to Stratford, Ontario to attend the Shakespeare festival held at the Globe. The play we saw almost never corresponded with the play we studied, but I guess it was still “a positive cultural experience.” When I was in college, I spent a semester abroad in England; as soon as I arrived, I was urged to go into town to see a production of The Tempest that was being held in Arundel Castle. That was the first time I saw Black actors performing Shakespeare! Caliban was Black, of course, but so was the prince Ferdinand (Miranda was white). That semester abroad didn’t live up to its auspicious beginning, and I haven’t really bothered with Shakespeare since then. But I really wanted to see this Harlem production with its incorporation of accents and actors from throughout the African diaspora. Ariel was probably my favorite—she sang and howled and enchanted the shipwrecked sailors, sometimes while suspended above the stage. And Prospero was fantastic, too. Not the ideal father but he understood that sometimes you have to trouble the water to get things done…

July 24, 2015

Surviving Santiago

I’m not a romantic, but when an author mixes love and politics—I’m in! I recently finished reading Lyn Miller-Lachmann’s latest YA novel, Surviving Santiago, and was intrigued by the central role played by the protagonist’s lesbian aunt. For a more comprehensive review of the novel, check out Cindy L. Rodriguez’s write-up over at Latin@s in Kid Lit. For more on the role of LGBTQ people in political movements, read on!

I’m not a romantic, but when an author mixes love and politics—I’m in! I recently finished reading Lyn Miller-Lachmann’s latest YA novel, Surviving Santiago, and was intrigued by the central role played by the protagonist’s lesbian aunt. For a more comprehensive review of the novel, check out Cindy L. Rodriguez’s write-up over at Latin@s in Kid Lit. For more on the role of LGBTQ people in political movements, read on!

ME: In this companion to Gringolandia, we see a shift in perspective. Tina is now telling the story, and since her mother has remarried a gringo back in Wisconsin, the only female figure in Tina’s life is her father’s sister Ileana. Can you explain your decision to use Ileana as an opportunity to critique patriarchal norms in Chile as well as homophobia? Tina’s father is a radical political activist who has devolved into a barely functional alcoholic after being tortured by the Pinochet regime. He is almost entirely dependent upon his sister and yet openly expresses contempt for her as a lesbian. What, if any, statement were you trying to make about the role of women and LGBTQ people in leftist movements–and in families?

LYN: Thank you for your thoughtful question about Tía Ileana, Zetta! I’ve written about the Chicana civil rights movement, in which LGBTQ people played a major role in confronting patriarchy and homophobia, and in reinterpreting various myths, such as La Malinche, that justified the subjugation of women. Chile’s history and traditions are somewhat different from Mexico’s, but the society is still a patriarchal one with many contradictions. For instance, many women have long worked outside the home, more so than in other Latin American countries, but they return to the “second shift.” Poor, immigrant, and indigenous women are frequently employed as domestic workers, leaving their own families behind to care for the homes and children of well-to-do Chileans. And while Chile was one of the first countries in Latin America to elect a female president, it has some of the harshest anti-abortion laws and lags behind several of its neighbors in granting rights to LGBTQ people.

Tía Ileana embodies some of these contradictions. Like many Chilean women who work outside the home, she returns to the second shift of housework and caretaking. While politically progressive, she works for a real estate developer in the neoliberal economy imposed by the Pinochet regime and its U.S.-based consultants. And she assumes the traditional role taking care of her disabled younger brother, a role that typically falls to unmarried family members because of the lack of social services, while maintaining her relationship with her partner, Berta.

Living with these contradictions takes an emotional toll on Tía Ileana. At first, Tina is unaware of her aunt’s struggle because she is so focused on her own sacrifice, having to spend her summer in Chile with her estranged father. Gradually, though, Tina comes to see her aunt as a mentor and to empathize with her. She learns that she can be true to herself while loving her father despite his flaws and without expecting that he’ll change.

In the context of a leftist movement, the significance of Tía Ileana’s—and Tina’s—unconditional love is this: Being involved in a progressive movement is hard. You’re fighting against those who have nearly all the power and resources, and in the case of the dictatorship, a willingness to use torture, disappearance, and murder to crush their opponents. It’s easy to give up or walk away. My characters’ (particularly Tía Ileana’s) refusal to give up on the people closest to them parallels their refusal to give up on their country. Ultimately, too, they need each other to survive.

In contrast to the violent beginning of the Pinochet dictatorship—a violence aided and abetted by the United States—the end of that dictatorship was accomplished through peaceful means. Pinochet lost the 1988 plebiscite despite his control of the media and the rules of the election. His opponents engaged in dialogue with people who had initially supported the coup and with those too frightened to speak out. Tía Ileana embodies the possibilities that come from reaching out to people who do not understand, a lesson that Tina absorbs as well. Just as the people of Chile had the courage to bring down the dictatorship through peaceful means, Surviving Santiago ends with the hope that Tina’s father will one day change his attitude toward LGBTQ people because of the courage, persistence, and generosity of those around him.

Lyn Miller-Lachmann is the author of the young adult novel Gringolandia (Curbstone Press/Northwestern University Press, 2009), about a teenage refugee from Chile coming to terms with his father’s imprisonment and torture under the Pinochet dictatorship. Gringolandia was a 2010 ALA Best Book for Young Adults and received an Américas Award Honorable Mention from the Consortium of Latin American Studies Programs, among many other accolades. Her second YA novel Rogue (Penguin/Nancy Paulsen Books, 2013), a Junior Library Guild selection, portrays an eighth grader with undiagnosed Asperger’s syndrome and an X-Men obsession, whose effort to befriend another outcast after being expelled from school leads her to some difficult and dangerous choices. Her latest novel is Surviving Santiago (Running Press, 2015), the companion to Gringolandia where younger sister Tina, now 16, travels to Chile at the end of the dictatorship in 1989 to visited her estranged father, and ignored by him, ends up falling in love with a mysterious local boy.

Lyn Miller-Lachmann is the author of the young adult novel Gringolandia (Curbstone Press/Northwestern University Press, 2009), about a teenage refugee from Chile coming to terms with his father’s imprisonment and torture under the Pinochet dictatorship. Gringolandia was a 2010 ALA Best Book for Young Adults and received an Américas Award Honorable Mention from the Consortium of Latin American Studies Programs, among many other accolades. Her second YA novel Rogue (Penguin/Nancy Paulsen Books, 2013), a Junior Library Guild selection, portrays an eighth grader with undiagnosed Asperger’s syndrome and an X-Men obsession, whose effort to befriend another outcast after being expelled from school leads her to some difficult and dangerous choices. Her latest novel is Surviving Santiago (Running Press, 2015), the companion to Gringolandia where younger sister Tina, now 16, travels to Chile at the end of the dictatorship in 1989 to visited her estranged father, and ignored by him, ends up falling in love with a mysterious local boy.

Lyn served as Editor-in-Chief for the quarterly journal MultiCultural Review for 16 years and has remained active in encouraging and promoting diversity in books for children and teens. She is a summer 2012 graduate of the Writing for Children & Young Adults program at Vermont College of Fine Arts and reviews children’s and young adult books on social justice themes for The Pirate Tree (www.thepiratetree.com). Lyn has lived in Portugal and speaks Spanish and Portuguese. Her debut translation from Portuguese, the picture book The World in a Second by Isabel Minhós Martins and Bernardo P. Carvalho, was published by Enchanted Lion in 2015. She blogs about writing, travel, culture, and LEGO at www.lynmillerlachmann.com.

July 16, 2015

race & representation in Asian American kid lit

I talked to a couple of people about it but felt it wasn’t my place to raise the issue. I support an artist’s right to write about whatever s/he likes, but if this was happening to this extent within the small community of Black authors and illustrators, I’d be taking names! Seriously. Kids of color are desperate to see themselves in books and I feel most artists in my community feel an obligation to provide those “mirrors.” It’s also a matter of self-determination/self-definition; we want to control the narratives and images our children consume. This is especially important when there are so many books about but not by Blacks, and popular culture is rife with racist stereotypes. In the Black community, we know the toll this takes on our kids; the misrepresentation of Black people fuels misperceptions that diminish self-esteem and can even cost a Black child her or his life.

But let me be honest—my interest in the comparative CCBC stats is not unrelated to my investment and participation in the kid lit diversity debate. I’ve had several conversations with Black women who feel excluded from the We Need Diverse Books movement, and Jessica Williams’ recent “ helper whitey ” skit perfectly illustrates how Black women routinely have their ideas dismissed by those who perceive them as “too angry.” At times, coalition building between Blacks and Asians here in the US has been hindered by the “model minority” myth coupled with anti-Black racism (though there are notable exceptions and the UK has a very different history). I’ve written about my own need to “ decolonize my imagination ” after growing up Black in a “former” British colony, and Sona Charaipotra and Dhonielle Clayton have developed a theory about “ cultural Stockholm syndrome .” All in all, this seems like a good moment to explore the challenges different marginalized groups face when representing race for young readers. To better understand the particular perspective of Asian American kid lit creators, I invited several people to join this virtual roundtable: Sarah Park Dahlen , Shveta Thakrar , Sona Charaipotra , Mike Jung , and Katie Yamasaki . I am hoping that this will be the first in a series of conversations about race and representation in children’s literature.

***

Me: What is your response to the CCBC stats on books by, about, by but not about Asian/Pacific Americans? Is the need for “mirror books” perceived as less urgent in the Asian American community? Do commercial considerations take priority or are authors/illustrators pressured to write outside their race?

***

Sarah: I was surprised and not surprised to see the rate at which we write outside our race. From my personal experience, I was raised to be proud of being Korean American, but my culture (and its absence in the media, popular culture, etc.) was not something I was encouraged to think about critically. When I decided to major in Asian American Studies, my parents wondered why I was doing something no one would be interested in, something that wasn’t attractive to a future employer. It didn’t fit with their idea of American Dream = lawyer/doctor/professor/engineer. So I don’t think we’re necessarily pressured to write outside our race, but we’re not often encouraged to write inside our race.

Sarah: I was surprised and not surprised to see the rate at which we write outside our race. From my personal experience, I was raised to be proud of being Korean American, but my culture (and its absence in the media, popular culture, etc.) was not something I was encouraged to think about critically. When I decided to major in Asian American Studies, my parents wondered why I was doing something no one would be interested in, something that wasn’t attractive to a future employer. It didn’t fit with their idea of American Dream = lawyer/doctor/professor/engineer. So I don’t think we’re necessarily pressured to write outside our race, but we’re not often encouraged to write inside our race.

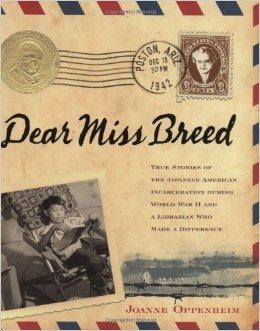

No author wants to be labeled solely as an “Asian American author” or an “African American author.” And truly, Asian Americans and people of all identities should tell whatever story they want to tell, but should consider what stories are left untold if we don’t tell our own stories, and what the stakes are if others tell our stories. An example of someone who writes well across experiences is Linda Sue Park – When My Name was Keoko (Japanese colonialism in Korea), Project Mulberry (contemporary novel that addresses race issues), and A Long Walk to Water (about a Sudanese Lost Boy and access to clean water). And often it’s complicated – in Half a World Away Cynthia Kadohata tells the story of a boy named Jaden who was adopted from Romania, and then accompanies his American parents to Kazakhstan to adopt another child. She herself is an adoptive mother to a child born in Kazakhstan, and the story is told from the perspective of the child adopted from Romania, so she is writing inside or outside her experience? Similarly, outsiders who write Asian American stories should consider what stake they have in telling our stories, whose voices they might be silencing in that telling, and whether or not they are the best person to tell that story. Gene Luen Yang, Allen Say, and Laurence Yep have made tremendous contributions to Asian American children’s and YA literature as insider authors, and in some sense they tell stories as outsiders when we consider their historical works (Boxers & Saints, the Golden Mountain Chronicles, etc), yet by and large we consider them insiders telling our stories. And there remain many stories that are untold, that should be told, if someone can do right by the story. A great example here is Joanne Oppenheim’s Dear Miss Breed: True Stories of the Japanese American Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian Who Made a Difference.

Similarly, outsiders who write Asian American stories should consider what stake they have in telling our stories, whose voices they might be silencing in that telling, and whether or not they are the best person to tell that story. Gene Luen Yang, Allen Say, and Laurence Yep have made tremendous contributions to Asian American children’s and YA literature as insider authors, and in some sense they tell stories as outsiders when we consider their historical works (Boxers & Saints, the Golden Mountain Chronicles, etc), yet by and large we consider them insiders telling our stories. And there remain many stories that are untold, that should be told, if someone can do right by the story. A great example here is Joanne Oppenheim’s Dear Miss Breed: True Stories of the Japanese American Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian Who Made a Difference.

Asian American authors writing about more non-Asian American topics may also be a function of the “don’t make waves” perspective that haunts our communities. After 120,000 Japanese Americans were interned during World War II, upon their release few Japanese Americans spoke out against the injustices they suffered and appeared to quietly assimilate, which led one reporter to call them the “model minority” (which is a hugely problematic myth). Decades later, people began to share their internment stories so we could learn about this ugly part of American history. Similarly, Koreans didn’t talk about the shame and trauma of Japanese colonialism, especially to their American children, until decades later. Despite growing up surrounded by Koreans, I didn’t learn about colonialism until college.The good news is that today we have multiple books depicting the Internment and Japanese colonialism, but are they enough? Every time I teach a children’s literature course, many of my students – mostly white – say they’ve never heard of the Internment, or colonialism, or anti-Chinese immigration history. Clearly, we need more books on these subjects.

Also, the phrase “diverse books don’t sell” has been floating around the industry, so why would an Asian American author or illustrator want to go up against that? And when diversity is included, what kind of diversity is valued? For example, APALA Literature Awards aren’t announced at the ALSC Youth Media Awards ceremony. It’s about survival in an industry that is not wholly inclusive of diverse voices.

There are many different Asian diasporic cultures and experiences, and we need more stories for all reading levels and in different genres. In particular, we need to hear more stories of Filipinos, Hmong, South Asian Indians, Pacific Islanders, and mixed-race Asians. I hope more Asian American authors will feel compelled to write mirror stories for our young people. I hope agents and editors will solicit our stories from our talented writers and illustrators. And I hope librarians, educators, and parents will work hard to connect young people with our stories.

Sarah Park Dahlen is an assistant professor in the Master of Library and Information Science Program at St. Catherine University.

Shveta: I have to say, this does not surprise me. I think it stems from a number of factors: even as we talk about the need for diversity, America is still steeping in a stew of whiteness. I didn’t think about writing characters of color until I was in my mid-twenties, and I’ve heard similar things from many other authors. And there’s still the idea that white is normal, so you’ll sell more if you write a white character, while you’ll be pigeonholed as a niche author if you don’t. (Which is nonsense, but . . .)

Shveta: I have to say, this does not surprise me. I think it stems from a number of factors: even as we talk about the need for diversity, America is still steeping in a stew of whiteness. I didn’t think about writing characters of color until I was in my mid-twenties, and I’ve heard similar things from many other authors. And there’s still the idea that white is normal, so you’ll sell more if you write a white character, while you’ll be pigeonholed as a niche author if you don’t. (Which is nonsense, but . . .)

So it doesn’t shock me. That said, I don’t think every author feels that way. I know I don’t–I’ve made a conscious decision to have my stories always star desi characters and often use Hindu/Buddhist mythology and folklore–and I’ve seen other authors say they are trying to do similar things–but they also don’t want to be boxed in. Why shouldn’t they be able to write whatever characters they want?

And that’s a valid point, except that we do have this awful power imbalance and this internalized assumption that everyone can relate to white people, that when you “don’t see color,” what you’re really saying is that you have no problem reading all white characters written by white people.

When things come down to money, I do think a lot of people will (reasonably enough) bend and do what is more likely to put bread and butter (or whatever food they eat) on the table. Of course, that keeps the extremely problematic status quo intact. So what’s the right answer?

I don’t know what the right answer is. I can’t tell anyone how to write. But I can encourage us to keep telling our own stories and be the ones to represent us. I can ask white authors to shine the spotlight on us, and I do. I definitely can keep my promise to keep writing about people who look like me, and I always will.

Shveta Thakrar is a writer of South Asian–flavored fantasy, social justice activist, and part-time nagini.

Mike: When I was in sixth or seventh grade I was enrolled in a summer enrichment program where I took a writing class. I remember writing a short story about an astronaut named Bill Starr, who was as white as white can be. He was definitively not Korean. Back then it would have been impossible for me to articulate why I created a character that looked like the people I was surrounded by and not like me, and it’s no walk in the park to articulate it now, although I do have more insight. Things might have been different if my family had stayed in Los Angeles for my entire childhood – we had family there, and a church whose routines I disliked but whose people I’d grown up with – but we moved to a neighborhood in northern New Jersey that was devoid of people of color, and the impact was lasting. I was a deeply insecure and probably neurodivergent boy, one who lacked the easy facility with people that my father and brothers possessed, and in retrospect, the lengths I went to in an effort to avoid feelings of persecution and derision were lamentable.

Mike: When I was in sixth or seventh grade I was enrolled in a summer enrichment program where I took a writing class. I remember writing a short story about an astronaut named Bill Starr, who was as white as white can be. He was definitively not Korean. Back then it would have been impossible for me to articulate why I created a character that looked like the people I was surrounded by and not like me, and it’s no walk in the park to articulate it now, although I do have more insight. Things might have been different if my family had stayed in Los Angeles for my entire childhood – we had family there, and a church whose routines I disliked but whose people I’d grown up with – but we moved to a neighborhood in northern New Jersey that was devoid of people of color, and the impact was lasting. I was a deeply insecure and probably neurodivergent boy, one who lacked the easy facility with people that my father and brothers possessed, and in retrospect, the lengths I went to in an effort to avoid feelings of persecution and derision were lamentable.

I made racist jokes about myself and about others. I renounced my heritage. I distanced myself from my family. I started and continued hearing comments about being a banana Asian or an imitation white boy, and instead of using those comments as motivation to engage in critical self-analysis, I used them as rationale to distance myself further from my own ancestry. I feel the effects of those wretchedly misguided choices to this day; I imagine I’ll feel them until my bones are in the ground. I’m not suggesting those choices were made by every Korean-American child who grew up in a predominantly white community, because there’s no single, universal narrative that applies to all of us. My brothers grew up in the same environment, but seemed to emerge more whole than I did—they certainly evinced less obvious self-loathing in following years, and had fewer obvious struggles than I did, although of course not all struggles are obvious.

What I think IS universal about my experiences is the way they were massively influenced by the society around me. The all-pervasive norms of white America really are pressed into our psyches with the percussive force of a jackhammer, especially through pop culture, and I was a greedy consumer of escapist entertainments. I also lacked the psychological and intellectual sophistication required to dismantle the model minority myth, and there were ways in which I swallowed the whole damn fishing rod in that way. I didn’t question talk of the innately disciplined and gifted nature of Asian-Americans, and I didn’t perceive the subtle dynamics of dominance and condescension that accompanied such talk. Compliance; obedience; acceptance of authority; I was the poster boy for those qualities.

Unlike so many who have spoken and continue to speak up, I have no history of meaningful activism, scholarly inquiry, or professional accomplishment in the realm of anti-racism work. I’m making an effort now, but making that effort has me feeling exposed in a way that’s entirely new to me. My perspective, which has always been thickly laden with uncertainty, has taken another yet another layer of uncertainty. That perspective is mine and mine alone, of course; it would be inappropriate to say that my emotionally complex life experiences or self-perceived limitations apply to any other Korean-American writer’s choice to create characters of (for example) white European descent. I also refuse to believe that writing characters whose racial and ethnic identities don’t align cleanly with our own is an invalid choice; as an author who I deeply respect said to me at a recent conference, we are not and shouldn’t be restricted to writing the racial and ethnic equivalent of memoir.

That said, I suppose I’ve been presenting one possible reason for the noticeably high percentage of Asian authors who write about non-Asian characters throughout this post. For me, fueling my work with my own experiences of racial identity is deeply uncomfortable; painful, even. It hurts to write a story that forces me to confront the places of disconnection within my heart and mind, and I’ve only recently committed myself to engaging in that process indefinitely, so there’s a long, snaking road of discomfort ahead of me.

That’s not the only potential reason, of course. I do believe the choice to write outside of our own experience does always involve an element of creative ambition. We have the desire and the right to push against our own creative boundaries; exploration is an essential part of the creative life. However, I suspect I’m not the only one contending with my particular brand of discomfort, and while I’m not exactly happy to contemplate that probability, it helps me to push onward. I want and need the help, because grappling with the discomfort is a necessary part of the process. It’s terribly, distressingly necessary.

Mike Jung is the author of the middle-grade novels Geeks, Girls, and Secret Identities (Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic, 2012) and Unidentified Suburban Object (Arthur A. Levine Books/Scholastic, 2016). He’s also contributed essays to the anthologies Dear Teen Me (Zest, 2012), Break These Rules (Chicago Review Press, 2013), and 59 Reasons to Write (Stenhouse, 2015). Mike is a founding member of the We Need Diverse Books team, and serves as a grant officer for the WNDB Internship Program.

Katie: Of course, everyone should be able to write about whatever they want. I think another question is what motivates some artists to reflect their experience and feel driven to tell their stories when other artists do not.

Katie: Of course, everyone should be able to write about whatever they want. I think another question is what motivates some artists to reflect their experience and feel driven to tell their stories when other artists do not.

From my own perspective, I was motivated to become a children’s book author/illustrator for the primary purpose of making a children’s book about the Japanese American internment camps. I had enough generations behind me where older generations of my family, unlike other Asian-American families I knew, told stories openly about this time. I was fortunate to grow up in a family that valued their own stories and our own history in the context of this country’s history (also it’s true what they say about Japanese people and cameras and we have family photos dating back to Okinawa in the late 1800s if that’s possible, so we had insane family records).

The second primary motivating factor for me was that I grew up just north of Detroit in a small town that was built around a GM auto plant. The entire culture of my town was based on the auto industry and was extremely conservative, white, working-class and during the recession of the 1980s, highly anti-Japanese. Vincent Chin was killed when I was 6 years old not too far from our home and the racism that inspired his murder was pervasive in mainstream Detroit culture throughout that decade. For me, as an artist and activist, it was formative. My idea to make a book about the internment came no more from poignant family stories than it did from racist U.S. history teachers asking me to address the class on the anniversary of Pearl Harbor. “You’re Japanese, Katie. Why don’t you tell the class what happened on that day in history.” That was always my opportunity to teach the internment, which I did, but you get the point. There were absolutely no books or teaching materials that I was aware of at that time that I could throw in my teacher’s face.

Last fall I spent a month at the Japanese American National Museum in LA doing a mural [Moon Beholders, below]. It was a wonderful experience, and full of interesting encounters with other JAs of my same (4th) generation. They found me to be “much less Japanese,” and I found them to be way less political. They grew up in a community of people with whom they identified racially and culturally. They grew up, in a community of people who had shared stories and a common past. They didn’t need to tell the story in order for it to be told. This geographic difference profoundly impacted the people we became and the type of work we were motivated to do and I found that to be really fascinating.

When I look at Asian and Asian-American author/illustrators in my children’s book class in SVA, and even my younger students (NYC public middle schoolers), it is extremely rare that students want to create stories that have elements of personal or cultural narrative. They are also, almost never, in the minority. Art schools these days are full of illustrators, especially from China and Korea. And although the stories that they often tell do not focus on an Asian main character (until we talk- or Zetta comes for a visit to the class and then they do), the aesthetic and feeling of the book is, in most cases, recognizably Asian. It’s hard to explain what this means, but if you were to give me a pile of student work with no names, I could 99% of the time identify the books created by the Asian author/illustrators.

When I look at Asian and Asian-American author/illustrators in my children’s book class in SVA, and even my younger students (NYC public middle schoolers), it is extremely rare that students want to create stories that have elements of personal or cultural narrative. They are also, almost never, in the minority. Art schools these days are full of illustrators, especially from China and Korea. And although the stories that they often tell do not focus on an Asian main character (until we talk- or Zetta comes for a visit to the class and then they do), the aesthetic and feeling of the book is, in most cases, recognizably Asian. It’s hard to explain what this means, but if you were to give me a pile of student work with no names, I could 99% of the time identify the books created by the Asian author/illustrators.