Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 24

October 11, 2018

silver skies

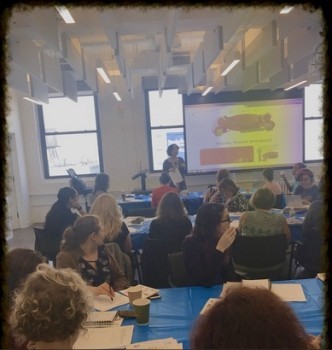

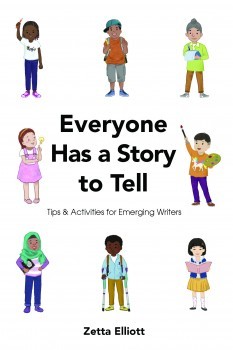

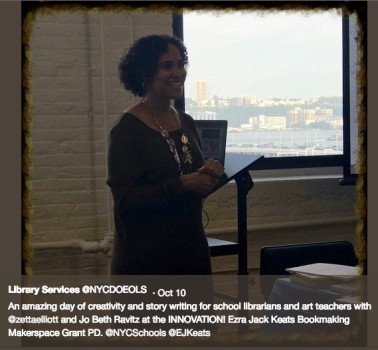

Yesterday morning I came out of Penn Station at 8:30 and immediately felt assaulted by the noise of midtown Manhattan—construction on every corner, roads choked with traffic, people racing by with sullen faces. My first thought was, “I don’t miss NYC at all!” Of course, I always made a point of saying I lived in Brooklyn. I avoided Manhattan as much as possible, and preferred the peaceful residential neighborhoods in my own borough. But then my Lyft arrived and being inside the car shut out some of the noise; by the time I reached our meeting place on 11th Ave., I was feeling calmer. Then I got upstairs, discovered my flash drive was NOT in my bag, and scrambled to get my presentation together. But the librarians attending the Ezra Jack Keats Bookmaking PD were ready to learn and ready to share—within minutes I forgot about not having had a bite to eat and we spent the next three hours writing! I brought copies of my new writing guide for everyone, and so far I’ve gotten some encouraging feedback. I’m

Yesterday morning I came out of Penn Station at 8:30 and immediately felt assaulted by the noise of midtown Manhattan—construction on every corner, roads choked with traffic, people racing by with sullen faces. My first thought was, “I don’t miss NYC at all!” Of course, I always made a point of saying I lived in Brooklyn. I avoided Manhattan as much as possible, and preferred the peaceful residential neighborhoods in my own borough. But then my Lyft arrived and being inside the car shut out some of the noise; by the time I reached our meeting place on 11th Ave., I was feeling calmer. Then I got upstairs, discovered my flash drive was NOT in my bag, and scrambled to get my presentation together. But the librarians attending the Ezra Jack Keats Bookmaking PD were ready to learn and ready to share—within minutes I forgot about not having had a bite to eat and we spent the next three hours writing! I brought copies of my new writing guide for everyone, and so far I’ve gotten some encouraging feedback. I’m  so grateful that Melissa Jacobs of the NYC Department of Education/NYC School Library System invited me to facilitate after seeing me present at the DOE Sexuality, Women, and Gender conference last spring. Deborah Pope, Executive Director of the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, gave everyone materials to take home—and I’m hoping I can find someone in Philadelphia who might want to get kids involved in the contest. After my workshop ended, I signed copies of BENNY DOESN’T LIKE TO BE HUGGED and MILO’S MUSEUM for the participants, gobbled down half a sandwich, and then walked back to Penn Station. The city was SO intense…I was relieved when I finally reached the Amtrak waiting lounge and dozed in the quiet car on the way back to Philly. Then I opened my eyes, looked out the window and for once, the sun was shining and the sky was blue. The train was crossing the Schuylkill, I could see rowers on the river, and the silver, mirrored skyscrapers were gleaming. And

so grateful that Melissa Jacobs of the NYC Department of Education/NYC School Library System invited me to facilitate after seeing me present at the DOE Sexuality, Women, and Gender conference last spring. Deborah Pope, Executive Director of the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, gave everyone materials to take home—and I’m hoping I can find someone in Philadelphia who might want to get kids involved in the contest. After my workshop ended, I signed copies of BENNY DOESN’T LIKE TO BE HUGGED and MILO’S MUSEUM for the participants, gobbled down half a sandwich, and then walked back to Penn Station. The city was SO intense…I was relieved when I finally reached the Amtrak waiting lounge and dozed in the quiet car on the way back to Philly. Then I opened my eyes, looked out the window and for once, the sun was shining and the sky was blue. The train was crossing the Schuylkill, I could see rowers on the river, and the silver, mirrored skyscrapers were gleaming. And  I was SO happy to be home again! I’m moving again this weekend (across the hall this time) and I’m trying to finish my first Philly novel by tomorrow. I have a few more NYC gigs this fall and I love that it only takes 90 minutes to move from one city to another. But I’m also glad that I left Brooklyn when I was ready because that means I can come and go without any emotional baggage. I believe Melissa took these photos during yesterday’s workshop, and I love that in this one you can see the Hudson River out the window. Rivers make me think of bridges and bridges are what keep us connected…

I was SO happy to be home again! I’m moving again this weekend (across the hall this time) and I’m trying to finish my first Philly novel by tomorrow. I have a few more NYC gigs this fall and I love that it only takes 90 minutes to move from one city to another. But I’m also glad that I left Brooklyn when I was ready because that means I can come and go without any emotional baggage. I believe Melissa took these photos during yesterday’s workshop, and I love that in this one you can see the Hudson River out the window. Rivers make me think of bridges and bridges are what keep us connected…

October 2, 2018

IndieLAB 2018

Conferences can be tricky because if you don’t find your people, you can feel very alone. For an introvert, mingling is hard so how does one find one’s people? Go to a conference where EVERYBODY is an indie author! IndieLAB was that rare space where I didn’t have to grovel and thank the organizer for including an indie in the line-up because the entire line-up consisted of people who either self-publish themselves or have advice for those who do. Not condescending advice—sound, generous advice designed to help you and your book succeed. My talk was partly about how we define success. I think some folks see me as the exception to the rule when it comes to self-publishing—they don’t *generally* like indie titles, but mine are pretty good. They might think that the attention some of my books have received means I’m earning lots of money from royalties, but that isn’t true. I make a living from speaking fees and so it was a real pleasure to address the attendees at IndieLAB in Cincinnati last weekend. I got a little pressed for time at the end and, of course, left my power cord at home so there were a few technical issues as well. But I thought I’d put my bullet points here on the blog so I can return to them as my idea of success evolves.

Conferences can be tricky because if you don’t find your people, you can feel very alone. For an introvert, mingling is hard so how does one find one’s people? Go to a conference where EVERYBODY is an indie author! IndieLAB was that rare space where I didn’t have to grovel and thank the organizer for including an indie in the line-up because the entire line-up consisted of people who either self-publish themselves or have advice for those who do. Not condescending advice—sound, generous advice designed to help you and your book succeed. My talk was partly about how we define success. I think some folks see me as the exception to the rule when it comes to self-publishing—they don’t *generally* like indie titles, but mine are pretty good. They might think that the attention some of my books have received means I’m earning lots of money from royalties, but that isn’t true. I make a living from speaking fees and so it was a real pleasure to address the attendees at IndieLAB in Cincinnati last weekend. I got a little pressed for time at the end and, of course, left my power cord at home so there were a few technical issues as well. But I thought I’d put my bullet points here on the blog so I can return to them as my idea of success evolves.

A successful indie author…

embodies possibility: be an example for others; do you best work but remember you don’t have to be perfect

serves her community, not just herself: think about the readers who need “mirrors,” support others in your community who share your values (teachers, librarians, nonprofits)

takes risks: don’t settle for the status quo—rustle feathers, rock the boat, and demand that the system recognize there’s more than one way to produce a book

supports a cause: care about something more than sales

operates in context: know the history of your field, recognize trailblazers, learn from others and share what you know

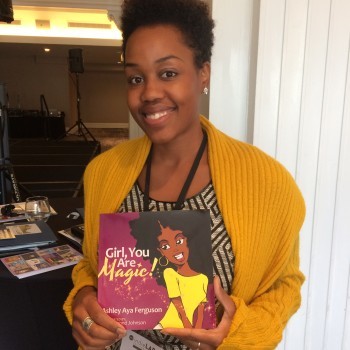

Afterward I had about a dozen people who waited in line to thank me for my talk and share their own projects, triumphs, and challenges. Last in line was Ashley who had seen our 2016 panel at the Books by the Banks Festival. She went ahead and self-published her first picture book and has a second in the works! Hearing that made my day and I passed along her beautiful book to an ecstatic little girl named Nia…

Afterward I had about a dozen people who waited in line to thank me for my talk and share their own projects, triumphs, and challenges. Last in line was Ashley who had seen our 2016 panel at the Books by the Banks Festival. She went ahead and self-published her first picture book and has a second in the works! Hearing that made my day and I passed along her beautiful book to an ecstatic little girl named Nia…

ALSC was also holding its annual conference in Cincinnati so I got to connect with several of my kid lit librarian friends over the weekend. They patiently let me rant about the bookseller who showed up to the  conference with NONE of my books. That’s happened more times than I can count so I wasn’t really surprised, but one would think that at an INDIE WRITERS CONFERENCE, the bookseller would make more of an effort. The booksellers here in Philly are proving more receptive and I’ve got a couple of invitations already. This morning I met a friend to tour the Mutter Museum, and she provocatively suggested I bring the building down at the end of my novel. I just might! I’m still a bit upset at the human specimens on display—did they ever give their consent to be treated as “curiosities?” I’m nearing 20K words with the novel and Christina Myrvold has agreed to do the cover. She knocked it out of the park with Mother of the Sea, so I’m ready to be wowed again. It was nice to see friends and meet new people in Ohio but I’m ready to hibernate and get this novel done!

conference with NONE of my books. That’s happened more times than I can count so I wasn’t really surprised, but one would think that at an INDIE WRITERS CONFERENCE, the bookseller would make more of an effort. The booksellers here in Philly are proving more receptive and I’ve got a couple of invitations already. This morning I met a friend to tour the Mutter Museum, and she provocatively suggested I bring the building down at the end of my novel. I just might! I’m still a bit upset at the human specimens on display—did they ever give their consent to be treated as “curiosities?” I’m nearing 20K words with the novel and Christina Myrvold has agreed to do the cover. She knocked it out of the park with Mother of the Sea, so I’m ready to be wowed again. It was nice to see friends and meet new people in Ohio but I’m ready to hibernate and get this novel done!

September 9, 2018

walking with the dead

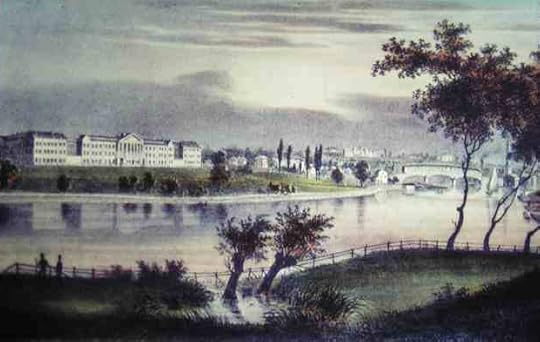

It feels like fall here in Philly, which is a nice change after last week’s heatwave. The temps won’t stay this low but for now it’s perfect writing weather. It rained all night and was still going this morning, but I went out for a run anyway; forgot my pedometer so all those steps didn’t “count,” but I knew I needed to be in the cemetery. The great thing about rainy days is that most people stay inside, so it feels like you have the city to yourself. I’ve started a new novel and it’s set in the cemetery and surrounding neighborhoods; I watched a lot of TV yesterday but I also worked out my summary and got a few chapters underway. I realize that I’m often thinking about doors—last week I was headed to the bank when I saw a freshly painted interior door resting against the outside of a corner house. The yard was a bit wild and the exterior of the house needed some work, but that lone door was perfect. I must have tucked that image away because it came back to me yesterday as I was writing. When I visited the website, I didn’t find any African Americans among the “notables” buried in Woodlands, but there was an adjacent orphanage, asylum, and poorhouse: Blockley.

So if my teen protagonist finds a lone Black boy in the cemetery, he might have been an orphan buried in a mass grave near Woodlands (1,000 burials were discovered in 2001 and reinterred at Woodlands). That area was considered rural in the 19th century even though Center City isn’t that far away from West Philly today. My second ghost is called Cin (short for Lucinda); she’s a Black woman wrongly committed to the asylum for working “black magic.” In reality she’s a psychic, a formerly enslaved woman who can sense portals that offer a way out for those in need. When her wealthy White mistress asks for her help, Cin complies and is then charged with her murder. I’m getting ahead of myself—a lot of this probably won’t end up in the book. But Cin matters because the protagonist’s mother is on disability due to mental illness; he’s terrified of having his mother taken away and so he’s become the adult in their household. But what he wants most is a place where his mother can heal, and Cin seems to offer that possibility.

So if my teen protagonist finds a lone Black boy in the cemetery, he might have been an orphan buried in a mass grave near Woodlands (1,000 burials were discovered in 2001 and reinterred at Woodlands). That area was considered rural in the 19th century even though Center City isn’t that far away from West Philly today. My second ghost is called Cin (short for Lucinda); she’s a Black woman wrongly committed to the asylum for working “black magic.” In reality she’s a psychic, a formerly enslaved woman who can sense portals that offer a way out for those in need. When her wealthy White mistress asks for her help, Cin complies and is then charged with her murder. I’m getting ahead of myself—a lot of this probably won’t end up in the book. But Cin matters because the protagonist’s mother is on disability due to mental illness; he’s terrified of having his mother taken away and so he’s become the adult in their household. But what he wants most is a place where his mother can heal, and Cin seems to offer that possibility.

It’s no coincidence that I’m writing about portals after watching Season 2 of Westworld; I’m also close to finishing Exit West by Mohsin Hamid. Think I’ll make another cup of tea and try to get an outline done for this new novel. For now I’m just calling it “Philly Story #1” because I’ve got two others in the works…

September 6, 2018

resist

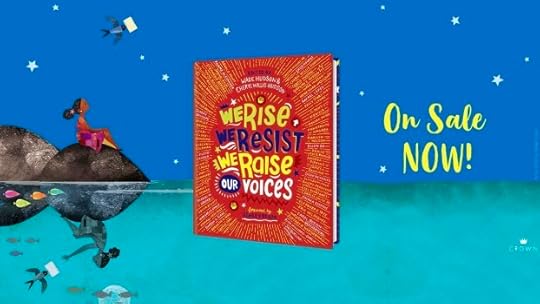

Our anthology is here! Many thanks to Cheryl and Wade Hudson, founders of Just Us Books, for responding to the 2016 election and the devastating “Trump Effect” that is harming so many of our kids. I’m honored to be included in this collection of esteemed writers. I hope you’ll add it to your home, school, or public library.

Our anthology is here! Many thanks to Cheryl and Wade Hudson, founders of Just Us Books, for responding to the 2016 election and the devastating “Trump Effect” that is harming so many of our kids. I’m honored to be included in this collection of esteemed writers. I hope you’ll add it to your home, school, or public library.

In a few weeks I’ll be delivering my keynote at the Writer’s Digest IndieLAB conference in Cincinnati. I recently did an interview for WD, which you can read here. The last question asked me to give a preview of my talk and here’s what I said:

I want to encourage people to think of storytelling as much more than a way to make money. Sharing your story can be therapeutic, empowering, educational—it isn’t always about selling thousands of books. In most cultures, stories are meant to connect people; it’s a way of building and maintaining community. So when I look at the current industry and consider all the voices that are being excluded, I have to wonder what that does to our ability to relate to one another. This is a nation of dreamers and I think our communities would be stronger if more of us found the courage to share our unique stories.

We’re suffering through a heatwave here in Philly. I try to run early in the morning and today decided to walk to Trader Joe’s to get my steps in—big mistake. I wore my new “Professional Black Girl” t-shirt that came in my Sisters in Education Circle swag bag, and it was soaked (and possibly sheer) by the time I reached the store. When I got to the checkout, the Black cashier immediately complimented me on my shirt—despite the sweat!—and we got to talking about the hot weather, my recent move to Philly, and how I write books for kids. She’s expecting her first and so I gave her one of my postcards and she immediately took out a pen and started circling the book covers that interested her. It’s those kinds of encounters that make me glad I do what I do. And I’m learning to focus on what matters—not how gross and sweaty I felt/looked but how warm and friendly Danielle was. Thinking I’ll take a couple books with me the next time I need groceries…

We’re suffering through a heatwave here in Philly. I try to run early in the morning and today decided to walk to Trader Joe’s to get my steps in—big mistake. I wore my new “Professional Black Girl” t-shirt that came in my Sisters in Education Circle swag bag, and it was soaked (and possibly sheer) by the time I reached the store. When I got to the checkout, the Black cashier immediately complimented me on my shirt—despite the sweat!—and we got to talking about the hot weather, my recent move to Philly, and how I write books for kids. She’s expecting her first and so I gave her one of my postcards and she immediately took out a pen and started circling the book covers that interested her. It’s those kinds of encounters that make me glad I do what I do. And I’m learning to focus on what matters—not how gross and sweaty I felt/looked but how warm and friendly Danielle was. Thinking I’ll take a couple books with me the next time I need groceries…

September 2, 2018

find the good

I walked into Center City today. On the way back I told my Lyft driver that I grew up taking the bus and always felt ashamed because my friends were driving their own cars or being driven by their parents. That shame has never gone away; I’m fine taking the subway but am still reluctant to take the bus as an adult. The past couple of weeks have been intense! Moving from Brooklyn to Philadelphia was very stressful, but I’m here now and I’m settling in pretty well. As I was packing I found an old bill from my therapist; I haven’t seen her since 2003, I think, and we only saw each other for about a year and a half; we tried to keep going with phone sessions, but that didn’t work and then I graduated from NYU and didn’t have health insurance….it was a long time ago yet I still recall the profound advice she once gave me: “The defenses that served you as a child may not serve you as an adult.” I realized late last week that I was depressed; I’ve lived with depression since I was a teen but my anxiety demands most of my attention and so sometimes it takes longer for me to realize when I’m feeling blue. The move was so stressful and after my plan to rent a car and drive down alone fell through, I finally asked for help from a friend—that’s not easy for me because I learned growing up not to rely on anyone else. To this day, there are things I won’t do or even try if I don’t think I can manage on my own. Because I’ve learned the hard way that people will let you down or just ghost when you need them. The end of summer is probably my toughest time of year when it comes to depression because I always see parents taking their kids to college and that didn’t happen for me. My folks just checked out and so my grandfather asked my uncle to drive me to the Ontario/Quebec border, and we waited there for my sister and her fiance to arrive from Montreal. We transferred everything from one car to another and I arrived at university several hours later with almost everything I needed—except my parents. And I’ve never forgotten that feeling, even though I still feel lasting gratitude that my sister—to whom I wasn’t close—showed up when I needed her and tried to give me the advice and support our parents couldn’t or wouldn’t provide.

I’ve moved so many times since that fall of 1990, and I almost always begin my new life by painting my new apartment. I got to Philly on a Wednesday and by that evening I’d located the nearest hardware store and walked over the next day to buy my first can of paint. My furniture arrived on Friday, and a week later I’d bought four more gallons of paint before I decided to take a break. There are some problems with the apartment and I’m not sure it makes sense to invest any more time or energy in making it beautiful if those problems can’t be fixed. I do NOT want to move again! I love the neighborhood and the building itself is full of friendly people, both residents and staff. But I need peace in my home. So what do I do? This morning, when the freight elevator woke me at 6am, I got up, finished painting the bathroom, and wrote a draft email to the property manager. Then I had breakfast, worked on my office (which is a mess), and decided to walk from 47th to the Target store at 19th St. When I got home, the concierge remarked, “So I hear you’re a children’s book author.” Turns out she stocks little “book nooks” around the community and is a volunteer literacy tutor at the school across the street! This morning I applied to be fingerprinted so I can work in Philly schools—starting with the elementary school next door. It has been fairly easy to get connected so far: I’ve joined the library and the local credit union, and will probably join the local food co-op, too; I found a farmers market in a nearby park, and figured out a good running route through a historic cemetery. And I’ve only been in Philly ten days! As a child/teen I believed I could make things better if I just worked hard enough. As an adult, I’ve learned that some things are beyond my control and sometimes you have to walk away. Other times, you’ve got to reach out and ask for help…which still isn’t easy for me. But on that first day at university, I was okay—my parents weren’t there but my sister was, and I made friends who eventually shared their own tales of family dysfunction, and our decorated dorm room became the most popular on the floor. What’s that advice Mr. Rogers gave to kids years ago? “Look for the helpers.” Because they’re always there—you just have to look around, and humble yourself a bit, and (for me) overcome your fear of being rejected. Lots of things are going well here in Philly so I’m going to try to stay positive and look for solutions to the problems that have come up. And I’ll be careful not to let my impulse to DO overwhelm my awareness of how I feel.

I’ve moved so many times since that fall of 1990, and I almost always begin my new life by painting my new apartment. I got to Philly on a Wednesday and by that evening I’d located the nearest hardware store and walked over the next day to buy my first can of paint. My furniture arrived on Friday, and a week later I’d bought four more gallons of paint before I decided to take a break. There are some problems with the apartment and I’m not sure it makes sense to invest any more time or energy in making it beautiful if those problems can’t be fixed. I do NOT want to move again! I love the neighborhood and the building itself is full of friendly people, both residents and staff. But I need peace in my home. So what do I do? This morning, when the freight elevator woke me at 6am, I got up, finished painting the bathroom, and wrote a draft email to the property manager. Then I had breakfast, worked on my office (which is a mess), and decided to walk from 47th to the Target store at 19th St. When I got home, the concierge remarked, “So I hear you’re a children’s book author.” Turns out she stocks little “book nooks” around the community and is a volunteer literacy tutor at the school across the street! This morning I applied to be fingerprinted so I can work in Philly schools—starting with the elementary school next door. It has been fairly easy to get connected so far: I’ve joined the library and the local credit union, and will probably join the local food co-op, too; I found a farmers market in a nearby park, and figured out a good running route through a historic cemetery. And I’ve only been in Philly ten days! As a child/teen I believed I could make things better if I just worked hard enough. As an adult, I’ve learned that some things are beyond my control and sometimes you have to walk away. Other times, you’ve got to reach out and ask for help…which still isn’t easy for me. But on that first day at university, I was okay—my parents weren’t there but my sister was, and I made friends who eventually shared their own tales of family dysfunction, and our decorated dorm room became the most popular on the floor. What’s that advice Mr. Rogers gave to kids years ago? “Look for the helpers.” Because they’re always there—you just have to look around, and humble yourself a bit, and (for me) overcome your fear of being rejected. Lots of things are going well here in Philly so I’m going to try to stay positive and look for solutions to the problems that have come up. And I’ll be careful not to let my impulse to DO overwhelm my awareness of how I feel.

August 5, 2018

trust your experience

That’s what James Baldwin said, and I try to follow his sage advice. When I’m asked to talk about self-publishing, I have no problem drawing from my own experience; my latest thoughts are on Jane Friedman’s website:

That’s what James Baldwin said, and I try to follow his sage advice. When I’m asked to talk about self-publishing, I have no problem drawing from my own experience; my latest thoughts are on Jane Friedman’s website:

When I self-publish, I’m showing what types of stories are getting rejected by traditional publishers. I’m affirming the value of the stories that matter to me and my community. Books are commodities but stories have more than commercial value in many cultures. When the traditional publishing industry says, “Your stories don’t matter to us,” it’s an act of resistance to walk away and make the book yourself. It’s also therapeutic and empowering! You don’t know what you can create on your own until you give yourself permission to experiment. That’s why I self-publish.

I plan to expand on this idea when I write my keynote for the Writer’s Digest IndieLAB conference next month. I want to emphasize how empowering it can be to be an indie author—especially in a moment when so many false and/or depressing narratives dominate the news. I’m limiting the amount of time I spend on Facebook, but I also think twice before posting accounts and/or recordings of police violence against Black people. Not because it doesn’t matter, but because it’s triggering to witness and relive that kind of brutality. The problem, however, is that my sensitivity around the representation of Black people made me blind to another kind of misrepresentation that’s outside of my personal experience. Yesterday I saw a video about a Black teen who connected with a White autistic teen who was watching him stock the shelves at a store in Louisiana. They ended up completing the task together, and the autistic teen’s father filmed the entire thing. That alone should have given me pause, but instead I focused on the Black boy wondering, with tears in his eyes, why people seemed so surprised/moved by such a simple act. It’s so rare that Black boys are shown as kind and considerate; WE know our brothers and sons are like that, but the dominant image of Black boys and men is the exact opposite. Fortunately, disability advocate Ashia Ray generously took the time to point out my blind spot. She gave me permission to share her comment so I added it to the post on my personal Facebook page and added a content warning (CW) for ableism and labor exploitation.

I agree with SO MUCH of what you post and the end notes to Benny [Doesn’t Like to Be Hugged] made me cry to see an allistic author consult an autistic person when writing a book about us.

But this makes me very sad and uncomfortable.

Allistic people get a LOT of praise of being even slightly decent people to disabled folks. They videotape it and post it on the internet and in the videos, we’re viewed as objects, infantilized, and again, expected to be elated when someone says a kind word or invites us to prom of whatever.

This – plus the fact that many of us are working for sub-minimum wage through government contracts where employers view our unpaid labor as a generosity – it feeds into he idea that our labor and worth as human beings is inherently worth nothing unless it serves as an inspiration for others.

Videos like this a harmful to us – particularly while many disability rights advocates are fighting for labor laws that take advantage of stereotypes that we just love working so much it’s a kindness to let us do it for free.

I hope you won’t delete this post, but are willing to address how problematic this feels and add a trigger warning to disabled people who have been used for inspiration porn and who have been exploited for free labor.

Ashia also shared a link to this article about the exploitation of disabled workers—please take the time to read it and reconsider how/if you share videos about disabled people on social media. Then check out her website Raising Luminaries, which has the best logo ever and features an incredible variety of truly inclusive books for kids.

Ashia also shared a link to this article about the exploitation of disabled workers—please take the time to read it and reconsider how/if you share videos about disabled people on social media. Then check out her website Raising Luminaries, which has the best logo ever and features an incredible variety of truly inclusive books for kids.

July 31, 2018

out with the old…

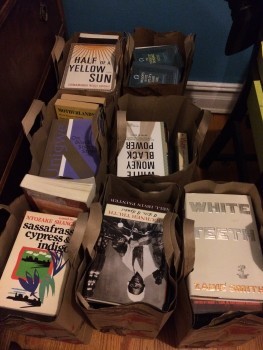

Last week I gave away eight bags of books and I’m taking the last bag to the Free Black Women’s Library tomorrow. Yesterday I recycled three old pairs of eyeglasses and today I took my two old laptops to Apple. I checked with the Sanitation Dept last night and if my Super fills out a form, they’ll come pick up my TV from 1995. Fifteen years ago Laura gave me a nightstand she found by the side of the road; yesterday I stained it to hide the damage caused by my humidifier—I didn’t quite follow the directions but it still looks pretty good. I want to buy a new rug for the living room but can’t bring myself to throw out the rattan one I’ve had for ten years…there’s got to be a way to mend the bits that are worn down. The fake leather is flaking off my ottoman; I’m thinking a staple gun and some gold-tinted African fabric should do the trick. I want a fresh start and that means unloading a lot of stuff that I don’t need anymore. But I don’t want to fill my new apartment with things I don’t really need. Strategic shopping and a little DIY—that should give me the kind of updates that will make my new home feel fresh and familiar. And with the money I save on new furnishings, I can pay for illustrations for a new picture book! I’ve got sixteen manuscripts and no takers so…

Last week I gave away eight bags of books and I’m taking the last bag to the Free Black Women’s Library tomorrow. Yesterday I recycled three old pairs of eyeglasses and today I took my two old laptops to Apple. I checked with the Sanitation Dept last night and if my Super fills out a form, they’ll come pick up my TV from 1995. Fifteen years ago Laura gave me a nightstand she found by the side of the road; yesterday I stained it to hide the damage caused by my humidifier—I didn’t quite follow the directions but it still looks pretty good. I want to buy a new rug for the living room but can’t bring myself to throw out the rattan one I’ve had for ten years…there’s got to be a way to mend the bits that are worn down. The fake leather is flaking off my ottoman; I’m thinking a staple gun and some gold-tinted African fabric should do the trick. I want a fresh start and that means unloading a lot of stuff that I don’t need anymore. But I don’t want to fill my new apartment with things I don’t really need. Strategic shopping and a little DIY—that should give me the kind of updates that will make my new home feel fresh and familiar. And with the money I save on new furnishings, I can pay for illustrations for a new picture book! I’ve got sixteen manuscripts and no takers so…

I just updated my list of spring presentations; I don’t put them all on my CV, but I do try to keep track of every paid and unpaid book talk or panel or writing workshop I conduct. I’ve already got a few NYC gigs booked for the fall—including a November 1 event for fifth graders at the BPL! I’ll also be traveling—last week I was invited to give one of two keynotes at the Writer’s Digest IndieLAB conference in Cincinnati. The program looks fantastic so if you’re an indie author or thinking of becoming one, join us! Turns out many of my radical librarian friends will be in Cincy that weekend for another conference so I’ll also get to join them for a pizza party…

We got our second starred review for DRAGONS IN A BAG from School Library Journal! I really appreciate how this reviewer teased out the overlapping themes in the story:

We got our second starred review for DRAGONS IN A BAG from School Library Journal! I really appreciate how this reviewer teased out the overlapping themes in the story:

Historically, most chapter books featuring magical tales of witches and dragons center the experiences of white protagonists and characters; Elliott offers something much needed in the genre: a black protagonist in an urban setting. Elliott skillfully introduces themes about creating positive change, examines issues of othering and the fear of differences, and touches upon the complexities of family, gentrification, and segregation. VERDICT A promising start to a new series, this fantasy should find a home in all libraries.

I also found out that MOTHER OF THE SEA has been selected as the August read for the State of Black Science Fiction book club! I have more exciting news about that title but can’t share yet…stay tuned!

July 19, 2018

heal thyself

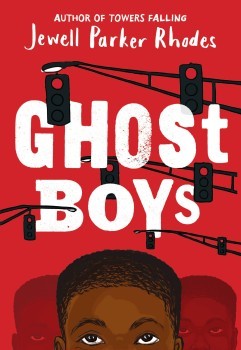

Lately I’ve been reflecting on the debt I owe so many Black women scholars. I stepped away from academia several years ago and have no regrets, but your training doesn’t leave you and it’s been energizing to find current scholarship that aligns with my kid lit writer’s goals. Graduate school feels like a lifetime ago and yet the scholars I discovered during that time have shaped the way I view the world. In fact, as I was reading Ghost Boys last month, I found myself trying to recall a quote by an esteemed Black woman scholar; only two words remained in my memory—“agonistic engagement”—so I searched my hard drive and up popped the first chapter of my dissertation, “’If Rigor Is Our Dream’: The Re-Membering of Violence by Black Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance.” Those two words are part of a passage from Hortense Spillers‘ seminal 1987 essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” which served as the theoretical backbone of my project. When I applied to graduate school in 1995, I only knew that I was interested in Black women’s quilts and Billie Holiday. One year later, I was at NYU taking a course on the Harlem Renaissance and my research focus had narrowed considerably. I knew Black women had been lynched but finding names and records proved challenging. Spillers helped me understand the erasure of Black women lynch victims from the historical record:

Lately I’ve been reflecting on the debt I owe so many Black women scholars. I stepped away from academia several years ago and have no regrets, but your training doesn’t leave you and it’s been energizing to find current scholarship that aligns with my kid lit writer’s goals. Graduate school feels like a lifetime ago and yet the scholars I discovered during that time have shaped the way I view the world. In fact, as I was reading Ghost Boys last month, I found myself trying to recall a quote by an esteemed Black woman scholar; only two words remained in my memory—“agonistic engagement”—so I searched my hard drive and up popped the first chapter of my dissertation, “’If Rigor Is Our Dream’: The Re-Membering of Violence by Black Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance.” Those two words are part of a passage from Hortense Spillers‘ seminal 1987 essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” which served as the theoretical backbone of my project. When I applied to graduate school in 1995, I only knew that I was interested in Black women’s quilts and Billie Holiday. One year later, I was at NYU taking a course on the Harlem Renaissance and my research focus had narrowed considerably. I knew Black women had been lynched but finding names and records proved challenging. Spillers helped me understand the erasure of Black women lynch victims from the historical record:

Indeed, across the spate of discourse that I examined for this writing, the acts of enslavement and responses to it comprise a more or less agonistic engagement of confrontational hostilities among males. The visual and historical evidence betrays the dominant discourse on the matter as incomplete, but counter-evidence is inadequate as well: the sexual violation of captive females and their own express rage against their oppressors did not constitute events that captains and their crews rushed to record in letters to their sponsoring companies, or sons on board in letters home to their New England mamas (73).

When a phenomenon like slavery—or lynching, or police violence—is framed as a struggle between men, the role of women gets obscured. In the above passage, Spillers implicates White women; they are involved and yet they are ignorant, they keep the home fires burning while the men in their lives enslave, assault, and exploit Africans. White male enslavers shield their delicate wives, sisters, and mothers from the truth, and this self-interested impulse to deceive/protect White women has been used to justify terrorizing Black people for centuries. Jessie Daniel Ames stood up to lynchers in the 1930s, but it’s important to remember that many White women supported mob violence, instigated and participated in lynchings, and even joined the Ku Klux Klan. To this day, when a White woman calls for help, White men respond with force—which is why #PermitPatty and #bbqBecky aren’t just funny memes. White women calling the police on Black people—even children—over a perceived threat can have deadly consequences.

Studying lynching for ten years changed me as a writer, and in some ways prepared me for this difficult moment in US history. Very little surprises me, though I’m often disappointed by the way some on the left respond to this latest surge of White supremacist violence. In a recent RaceBaitR essay, Zaire Bidgel laments the fact that it’s “so rare that Black people are given space to fully express their pain. There is always a label applied to it. It’s too loud, too violent, too painful, too much.” Most Black people realize that “our healing is solely our responsibility,” and yet there is continuous pressure in a White supremacist society to put the needs of the dominant group first (see the recent calls for “civility”). But Bidgel rightly asks, “How can we, as Black people, heal with white needs at the center of our thoughts and processes? How can we truly support ourselves and emotional wellbeing while serving the needs of those who continue to actively oppress and enact violence against us?”

The answer, of course, is that we can’t. The theorizing of Nancy Armstrong and Leonard Tennenhouse helped me to consider not just the representation of violence but also the violence of representation. As I’ve written elsewhere, the kid lit community likes to think of itself as a group of progressive adults who prioritize the needs of children and teens. Yet #DiversityJedi scholars have demonstrated that good intentions aren’t enough when writing about traumatic historical events. The choices made by writers, illustrators, and publishing professionals can produce books that are inaccurate, offensive, and even harmful to young readers. For Bidgel,

Pre-empting Black healing for the comfort or needs of whiteness is violence. We have lost so much of ourselves, our families, our communities, in (often forced) support of whiteness, regardless of if we see or acknowledge it. Interrupting expressions of Black pain and healing to think of the needs of white people, who have a direct hand in the pain we’ve been dealt is dehumanizing. It serves as a reminder that white needs must always be considered.

Which brings me back to Ghost Boys. Bidgel isn’t writing about books for young readers but their analysis of race dynamics in the nonprofit arena immediately made me think of another White-dominated space: the publishing industry. In an interview on WNYC, Jewell Parker Rhodes explained that she chose to include the character Sarah in order to humanize her father—a White police officer on trial for killing a Black boy named Jerome. Bullied at school, Jerome accepts a toy gun from a new friend and experiences a rare moment of freedom while pretending to be a cop. Then someone calls 911, the dispatcher leaves out important details when notifying the police, and the outcome mirrors the 2014 killing of Tamir Rice in a Cleveland playground: two White officers arrive, one immediately shoots Jerome in the back. They fail to provide life-saving procedures, are slow to call an ambulance and as a result, Jerome dies.

The courtroom scenes in the book are hard-hitting, but when it comes to Jerome’s interaction with Sarah, there are some surprising silences. When Jerome realizes only his murderer’s daughter can see him he asks, “‘Why can’t it be Kim who sees me? Why this stupid girl?’” (53). A second Chicago “ghost boy” arrives to answer Jerome’s question; Emmett Till, fourteen-year-old victim of an infamous 1955 lynching in Mississippi, urges Jerome to devote his afterlife to helping Sarah instead of his grieving sister Kim:

“Believe this, Jerome. It matters that Sarah can see you.”

“And I’m supposed to help her?”

“Got anything better to do?”

“Got me. Absolutely nothing.” (103)

The fact that Jerome’s family can’t see him makes helping them impossible and makes the White girl his priority. With Emmett’s guidance, Jerome begins to see Sarah as a victim much like himself: “She wants quiet, too. Protestors picket outside her house. Sarah keeps her window closed. Her world is upended. I get that. Sarah’s almost as messed up as me” (106). Except, of course, Sarah hasn’t had her life violently, prematurely, and unjustly terminated by a racist cop. Initially Jerome expresses justifiable anger and resentment towards Sarah, though his conditioning interferes:

Stop crying, I want to shout. Instead I mutter, “Your bed is nice. Pretty.” Being nice is automatic. How stupid to be nice. I always tried. What did it get me?

I’m getting angrier and angrier. I explode. My hand connects. Peter Pan flies across the room. The book hits the wall, drops to the floor…

Sarah’s eyes are different now. Frightened again. Nervous.

Ghost boy shakes his head like he’s disappointed in me. Not fair, I think. I holler: “Why do I need a white girl looking after me?”

“You’re right. But maybe you’re supposed to do something for Sarah?”

“Naw, naw. That’s sick. Her dad kills me and I’m supposed to help? Who are you anyway?”

“Emmett. Emmett Till.”…

“You’re the Chicago boy? Murdered like me?”

“1955. Down South.’” (96-97)

Unlike other novels where Black authors introduce White characters by having their Black protagonists attend predominantly White schools, Rhodes chooses to have her ghost boys float into Sarah’s bedroom. This, to me, is a shocking and potentially subversive decision given that Black men and boys historically have been cast as rapists desperate for contact with “pure” White women (allegedly because Black women were not “true” women, which made them unappealing to Black men and vulnerable to being raped by White men). Anti-lynching crusader and journalist Ida B. Wells proved that most lynchings were not about rape at all, but the sexual assault of White women was “beyond the pale” and made Black males deserving of the most brutal torture and death. Having Jerome compliment Sarah on her nice, pretty bed before lashing out violently brought to mind scenes from DW Griffith’s 1916 film Birth of a Nation:

“A curtain flutters. I see the girl. Like magic, I float inside, into the second floor and a pink bedroom.

The girl stumbles, falls against her dresser. She wants to scream, I can tell. But she doesn’t” (63).

The subversive potential of this scene is lost, however, since the child reader has not been informed—and likely would not know—about White women’s specific role in the lynching dynamic. Jerome has had “the talk” with his father: “How many times had I heard: ‘Be careful of police’; ‘Be careful of white people…’ Everybody in the neighborhood knew it. Pop told me as soon as I could read” (69-70). Jerome also learns about Black history from his father: “Slavery was awful. Afterwards, Pop said the KKK began lynching” (147). When he is shot, Jerome’s grandmother repeatedly references Emmett Till yet no one seems to have told this Black boy specifically to stay away from White girls. So Jerome has no idea that—were he still alive—entering Sarah’s frilly pink bedroom could have cost him his life in another era (and see the recent case of a White cop falsely arresting his daughter’s Black boyfriend). As a result, Jerome feels no anxiety about their encounter. Instead, his interactions with this White girl have a strangely romantic undertone; when he’s near Sarah, Jerome smells lilacs and when she looks up at him, “Her eyes are real; they have depth; they’re ice blue, sparkling with tears” (181). At first, Jerome admits, “If she wasn’t a girl, I’d think about hitting her” (64) but soon he’s apologizing for being “mean” and Jerome wishes he could hug and be hugged by Sarah (110).

Jerome effectively becomes Sarah’s protector, urging her not to watch the video of his death: “I don’t know why I’m saying this. Crazy, part of me doesn’t want to see Sarah hurt” (107). When Sarah asks a White Jewish librarian at her school to see the image of Emmett Till in his open casket, Jerome turns away: “I don’t want to see. Dead is dead. Doesn’t matter what dead looks like” (117). It does matter, of course, which is why Mamie Till Mobley insisted that the world see what Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam had done to her son. But it is Sarah who insists on viewing the disturbing image and by the end of the novel, she has become radicalized. Jerome convinces her to reconcile with her father who, by the end of the trial, “looks beat down” (121). Jerome only witnesses his own family’s suffering but he actively works to reunite the White family: “Sarah isn’t speaking to her dad. I don’t know why but it bothers me. Bad” (177). Having rejected his own legitimate Black rage, Jerome becomes the role model Sarah needs:

“I hate him. Don’t you?”

Do I?

Ma, Pop, Grandma taught me it’s wrong to hate. “No, I don’t hate your dad. You shouldn’t either.”

“He killed you.”

“He made a mistake.”

“He’s racist.”

“He made a mistake. A bad one.” Real bad.

Just like it was bad for Mike, Eddie, Snap to bully me. Bully Carlos.” (179)

At Jerome’s urging, Sarah focuses on her father’s redeeming qualities and asks him to help her launch a website dedicated to raising awareness of Black boys killed by police. Officer Moore agrees, and Jerome concludes that “Sarah’s going to be fine. She’s a white girl but she’s not ‘white girl.’ She’s Sarah. Me and all the other boys on her computer screen have names. Jerome Rogers. Tamir Rice. Laquan McDonald. Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Jordan Edwards. We’re people. Black kids” (184). Jerome concludes that “Sarah’s dad and Emmett’s killers, lived life wrong” (182-3) and finds his place within the “crew” of ghost boys: “I understand now. Everything isn’t all about me” (147). For Sarah, the future looks bright; Jerome sees her “grown, writing books, protesting for change. Teaching people how to see other people. Teaching her kids (imagine, Sarah, a mom!) to learn, not judge” (183).

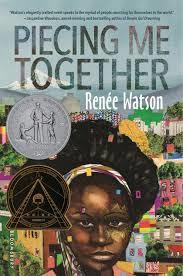

By contrast, Jerome’s sister Kim grieves and memorializes her brother privately with Carlos and Jerome’s former bullies as her new brothers/protectors. Perhaps in time Kim will follow in the footsteps of so many Black women and girls who turn their grief and righteous Black rage into : Samaria Rice, Tamir Rice’s mother, just opened a youth center in her son’s name; Lezley McSpadden, mother of Michael Brown, is running for political office in Ferguson. In the award-winning novel Piecing Me Together, Renée Watson’s teenage protagonist Jade responds to the trauma of another Black girl being brutalized by police by mobilizing her friends and community members.

By contrast, Jerome’s sister Kim grieves and memorializes her brother privately with Carlos and Jerome’s former bullies as her new brothers/protectors. Perhaps in time Kim will follow in the footsteps of so many Black women and girls who turn their grief and righteous Black rage into : Samaria Rice, Tamir Rice’s mother, just opened a youth center in her son’s name; Lezley McSpadden, mother of Michael Brown, is running for political office in Ferguson. In the award-winning novel Piecing Me Together, Renée Watson’s teenage protagonist Jade responds to the trauma of another Black girl being brutalized by police by mobilizing her friends and community members.

I don’t know how many daughters of White cops accused of shooting Black people have become anti-racist activists. I suspect Rhodes’ depiction of Sarah Moore is purely aspirational, and art can show us what’s possible alongside what is real. But I do wonder why Rhodes chose to include Emmett Till in this narrative if she was unwilling to fully unpack the painful history of lynching. The author takes time to explain the alleged whistle that prompted Till’s murder, but doesn’t explain why an accusation made by a White woman against a Black boy led to such a horrific act of violence. In the afterword, Rhodes explains her aim in writing Ghost Boys: “Through discussion, awareness, and societal and civic action, I hope our youth will be able to dismantle personal and systemic racism” (206). Yet in the list of resources provided at the back of the book, one finds a link to Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech but nothing on lynching.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice recently opened in Alabama. Ashley Akunna contends that police brutality is the evolution of lynching. Three senators just introduced a bill because lynching still isn’t a federal hate crime. Last week the Emmett Till case was reopened by the Justice Department, and Carolyn Bryant has admitted that her accusations against Emmett—whistling, flirting, grabbing—were false. So it’s a good time to tell the truth about lynching. But can that be done in a middle grade novel? Some will no doubt argue that the subject matter is too grim and/or too mature for young readers, yet anti-bias expert Louise Derman-Sparks reminds us that “it is developmentally appropriate for children to deal with ‘controversial issues’ such as prejudice and fairness,” and “learning to engage in critical thinking about what is true about people’s actions is fundamental to becoming a citizen of a democratic country.” Can this particular truth surface in a publishing industry and kid lit community dominated by White women? Is that why these “Becky books” diminish Black rage and White culpability (Blacks are always “just as bad” as Whites)? I don’t want these books banned or stripped of their awards and starred reviews. If I were still a professor, I would teach these books; like all novels, they have strengths and limitations. What I’m most interested in is the pattern, and I think readers should ask why Black girls are being marginalized and/or erased from these narratives about police brutality. Why are Black authors choosing instead to put White girls at the center of their stories? Hopefully we’ll see more Jades and fewer Beckys in future novels about anti-Black violence.

June 26, 2018

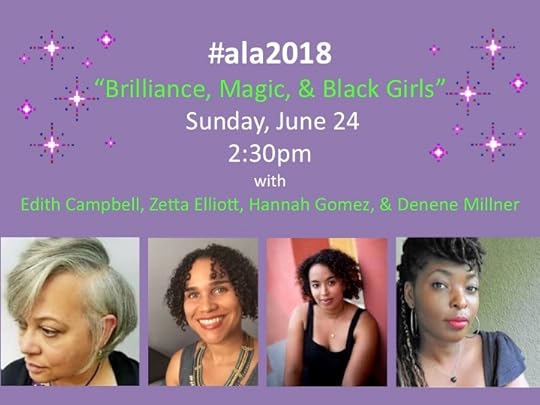

ALA 2018

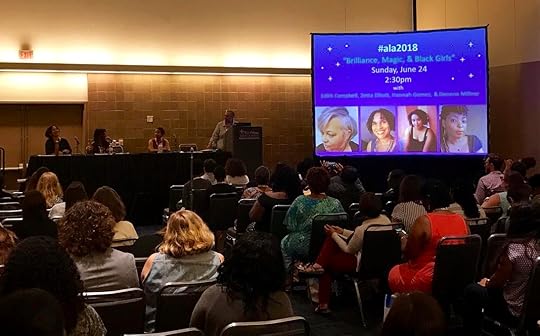

Whew! #ALA2018 was a one-day whirl. I got home yesterday afternoon, had a late lunch, and then fell asleep on the couch for more than 12 hours! I had to wake at or before dawn on both days, so I did lose a little sleep—but it was worth it. The CSK Awards breakfast, which started at 7am on Sunday, was full of moving speeches and moments of real fellowship. I had great conversations with Alia Jones, Miss Fabularian, and CSK Illustrator Award winner Ekua Holmes (pictured above with fellow winner Renee Watson) about problems in publishing and within our own Black kid lit community. Thanks to Edith Campbell we had a reserved #DiversityJedi table and so I got to meet new allies and connect with longtime friends.

Whew! #ALA2018 was a one-day whirl. I got home yesterday afternoon, had a late lunch, and then fell asleep on the couch for more than 12 hours! I had to wake at or before dawn on both days, so I did lose a little sleep—but it was worth it. The CSK Awards breakfast, which started at 7am on Sunday, was full of moving speeches and moments of real fellowship. I had great conversations with Alia Jones, Miss Fabularian, and CSK Illustrator Award winner Ekua Holmes (pictured above with fellow winner Renee Watson) about problems in publishing and within our own Black kid lit community. Thanks to Edith Campbell we had a reserved #DiversityJedi table and so I got to meet new allies and connect with longtime friends.

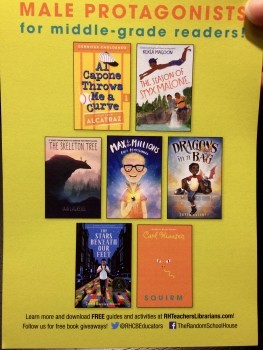

Edi and I went to the exhibits hall afterward; I stopped by the Random House booth but didn’t find DRAGONS IN A BAG on display anywhere. It *was* on their postcard and I saw people with ARCs, so hopefully that means it was out at some point during the convention. We scooped up books and met more friends and colleagues before venturing into the humidity to find a place to eat. Then it was time for our panel! I think Edi said 25 people had registered but we had a FULL house with folks standing and sitting on the floor. Edi moderated an excellent conversation about brilliance, magic, and Black girls before we wrapped up and shared our accompanying book list.

Edi and I went to the exhibits hall afterward; I stopped by the Random House booth but didn’t find DRAGONS IN A BAG on display anywhere. It *was* on their postcard and I saw people with ARCs, so hopefully that means it was out at some point during the convention. We scooped up books and met more friends and colleagues before venturing into the humidity to find a place to eat. Then it was time for our panel! I think Edi said 25 people had registered but we had a FULL house with folks standing and sitting on the floor. Edi moderated an excellent conversation about brilliance, magic, and Black girls before we wrapped up and shared our accompanying book list.

I finally met my agent Jennifer Laughran later that evening (for yet another sumptuous meal) and then woke early the next day to catch my flight back to NYC. SO grateful to my dear friend Karen Ott who showed me the city in a way only a local can—and got me to and from the airport, which saved me a pretty penny (conferences can be SO expensive, especially when it’s too hot & humid to walk anywhere).

I finally met my agent Jennifer Laughran later that evening (for yet another sumptuous meal) and then woke early the next day to catch my flight back to NYC. SO grateful to my dear friend Karen Ott who showed me the city in a way only a local can—and got me to and from the airport, which saved me a pretty penny (conferences can be SO expensive, especially when it’s too hot & humid to walk anywhere).

Working on clearing my inbox now and need to get to the park for a run. Then it’s back to work! Conferences—the good ones, at least—always leave my brain buzzing…

June 21, 2018

trust is earned

It’s been two weeks but I’m still thinking about my experience at the SWaG conference. The auditorium where I delivered my keynote—“SAY HER NAME: Respect, Resistance, and the Representation of Black Girls”—was more of an amphitheater. I stood at ground level and ringed above and around me were about 75 educators; behind me was the screen with photos of Kimberlé Crenshaw, legal scholar and executive director of the African American Policy Forum (which launched the in 2015), and the three founders of the Black Lives Matter movement: Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi. Midway through my talk I introduced quotes from members of the Black Girls’ Literacies Collective (BGLC), but I couldn’t use all the material I culled from the special issue of the NCTE journal English Education. I finished reading Ghost Boys last week and thought I would frame my discussion of the MG novel with a few pearls from three of the five members of the BGLC.

It’s been two weeks but I’m still thinking about my experience at the SWaG conference. The auditorium where I delivered my keynote—“SAY HER NAME: Respect, Resistance, and the Representation of Black Girls”—was more of an amphitheater. I stood at ground level and ringed above and around me were about 75 educators; behind me was the screen with photos of Kimberlé Crenshaw, legal scholar and executive director of the African American Policy Forum (which launched the in 2015), and the three founders of the Black Lives Matter movement: Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi. Midway through my talk I introduced quotes from members of the Black Girls’ Literacies Collective (BGLC), but I couldn’t use all the material I culled from the special issue of the NCTE journal English Education. I finished reading Ghost Boys last week and thought I would frame my discussion of the MG novel with a few pearls from three of the five members of the BGLC.

So—what are these scholars talking about when they suggest there’s something distinctive about Black girls’ relationship to literacy? In “Centering Black Girls’ Literacies: a Review of Literature on the Multiple Ways of Knowing of Black Girls,” Gholnecsar E. Muhammad and Marcelle Haddix explain it this way:

First…Black girls can know; simply stated, they have a voice. Black girls are generators and producers of knowledge, but this knowledge has been historically silenced by a dominant, White patriarchal discourse. Second…Black girls exhibit philosophies and practices that are distinguished from those of other groups. Third, Black girls represent two marginalized groups based on race and gender; however, this location cannot be simplified or generalized. The study of and with Black girls is complex…an intersectional lens is required to understand the literacy experiences of Black girls. (304)

Why should we care about how Black girls understand, engage with, and produce narratives? According to Muhammed and Haddix, “if we reimagine an English education where Black girls matter, all children would benefit from a curricular and pedagogical infrastructure that values humanity” (329). This quote immediately brought to mind a line from the Combahee River Collective’s 1977 “Statement:” “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

In “Why Black Girls’ Literacies Matter: New Literacies for a New Era,” Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz argues that “restructuring the way we engage with Black girls in our classrooms, and maintaining accountability—as teachers and as members of school communities—is essential for their success” (294). Although Sealey-Ruiz is primarily addressing English educators, her recommendations have broader applications; as an author who writes for kids and teens, I certainly think of myself as a member of school communities, and feel I should also be held accountable for my professional practices. Just as English education can become “a site of possibility and disruption,” so can the production, assessment, and distribution of books for young readers. The kid lit community has the capacity to serve as a “space for resistance and for the educational excellence of Black girls” (295). Sealey-Ruiz contends that “we have the power to change the way Black girls are talked about” by “investigating their reality” and carefully considering the texts used in the classroom (295).

Blacks girls know from an early age just how they’re talked about in our society. Sealey-Ruiz opens her essay with a statement composed by four Black female high school students from the Bronx; the young women note that online, Black girls are routinely objectified and shamefully reduced to “their mere parts” (291). Haddix and Muhammad cite another study where “researchers found that eight Black adolescent girls (ages 12-17) felt that the media portrays Black girls as being judged by their hair; seen as angry, loud, and violent; and sexualized” (321). So what happens when this misrepresentation of Black girls is perpetuated instead of being refuted by Black authors?

Sealey-Ruiz cites a Facebook post by education researcher Monique Lane who contends that the lack of outrage around, and mobilization against, violence targeting Black girls in schools “encourages young Black girls to trust no one. It reminds us that we cannot count on other folks to have our backs. Not our peers. And sadly, not even our teachers” (292). Lane was writing in response to the 2015 assault against a Black female student at Spring Valley High School. But it made me wonder how Black girls perceive members of the kid lit community. Do they believe we have Black girls’ backs? When it comes to books for young readers, who can be trusted to put the interests of Black girls first when Black women make up just 0.01% of YA authors in the US and the publishing industry is dominated by White women?

WASHINGTON, DC – MARCH 24: Eleven-year-old Naomi Wadler addresses the March for Our Lives rally on March 24, 2018 in Washington, DC. Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, including students, teachers and parents gathered in Washington for the anti-gun violence rally organized by survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting on February 14 that left 17 dead. More than 800 related events are taking place around the world to call for legislative action to address school safety and gun violence. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Trust is earned. When considering Black girls’ relationship to stories, Sealey-Ruiz reminds us that “attention to their humanity is vital” (291). The African American Policy Forum is helmed by a Black woman. The Black Lives Matter movement was founded by three Black women. At the March for Our Lives, 11-year-old Naomi Wadler demonstrated #BlackGirlBrilliance when she gave an impassioned speech about violence against Black women and girls. Why are these powerful Black female activists not represented in novels for young readers that address police violence against the Black community? And why isn’t this erasure apparent and/or important to so many editors, reviewers, and readers?

I’ve got dozens of quotes from Ghost Boys that I’d like to explore, but ALA is this weekend so my review will have to wait. Right now I’m thinking perhaps what’s needed are some guidelines to help readers assess the representation of Black girls in books for young readers. In “Imagining New Hopescapes: Expanding Black Girls’ Windows and Mirrors,” SR Toliver reflects on Rudine Sims Bishop’s metaphor and points out the favored narratives that limit our ability to recognize the fullness of Black girlhood:

…the mirrors of Black girlhood are narrowed because they exclude Black girls from across the African Diaspora, confine Black girls to certain geographical regions, and limit the representation of older adolescents to stories centered around harsh, urban existences. The findings also suggest that the windows into Black girlhood are opaque because the exclusion of multiple representations of Black girlhood creates a slender opening through which to view the intricate and complex experiences of Black girls.

For our panel on Sunday we’ve put together a list of sixty books that demonstrate and celebrate the ingenuity, creativity, courage, and excellence of Black girls and women. But sixty books—or even a thousand—can’t fully represent the varied experiences of Black girls. I think it’s time we turned more Black girls into writers—published authors—so they can tell their stories themselves…