John Elder Robison's Blog, page 10

January 13, 2013

The Leica, and rangefinder photography in today's world

When people see my little Leica camera they sometimes ask

why I still use it, with all the automated alternatives today. Why don’t I use a “real” camera, like a

Nikon? In fact, I have several Nikon

professional SLRs, and I’ve got some pocket point and shoot cameras as

well. Each are “real” cameras, and each

one has its place.

Interestingly, when people look at the images rendered by the Leica, no one questions my selection of photographic tool. My Leica images are sharp, with good

three-dimensional feel and very smooth rendering of the out-of-focus

areas. Color is good, and the images are

free of distortion and artifacts.

But of course the same can be said for images from my Nikon D3S

or a comparable Canon pro SLR. What makes Leica images different? That’s a question I’ve been pondering all

week. . .

Many people have written about the look, feel and quality of Leica cameras and lenses. There's no denying they are beautifully made, top quality products. The fact that there is an active market trading Leica items from the 1950s, 60's and 70's is testament to their longevity, and collectibility. That, however, is something for others to write about. I'm interested in image making ability, and final image quality.

There was a time when lens design set Leica apart from other

compact camera makers. Leica images were

sharper, more defined, and in myriad other ways set the standard for compact

camera/lens performance. That’s not so

true today. Comparison images shot with

identical settings using Leica and Nikon/Canon’s best lenses are

indistinguishable to me.

Today, what sets the images apart is the way in which the

camera systems are used. The Leica,

lacking automation, is used in a slow, deliberate way. Pro SLRs, in contrast, are often used as high

performance point and shoot action cameras, where the photographer composes

images quickly and often under adverse conditions, and relies on the automation

in the camera to return a good exposure.

Most of the time, the automation works, and it’s reshaped

the face of documentary photography.

Fast focus tracking has made it possible to shoot close ups of batters

hitting balls and the expressions on the faces of race car drivers going 200

miles an hour. The ability to switch ISO

from shot to shot makes it possible to walk from bright sun into a dim room and

never miss a frame.

Powerful lenses have allowed photographers to zoom into a

scene, isolating it from the surrounding background and increasing the impact

of the imagery. Extremely sensitive

sensors make it possible to take available light snapshots in near-darkness;

something we simply didn’t do before.

Yet we pay a price for using that automation. When we stand behind the lens, tracking a

fast-moving basketball or a bird in flight we lose our sense of the wider

world. Our reality becomes that one tiny

speck we see in the viewfinder, and our images are shaped accordingly.

The rangefinder camera – and this is best exemplified in the

Leica – calls for a totally different approach.

There are no powerful zoom lenses.

Most rangefinder lenses have an ordinary or wide field of view. In addition, the viewfinder shows the whole

scene, extending well beyond the limits of what the lens will capture.

That difference requires the photographer to see and

understand the whole scene, rather than the tiny bit he’d see through a 200mm

zoom. With that perspective, his

compositions will inevitably be different.

In some cases, they will be more realistic and natural to viewers as the

perspective of the picture is closer to the perspective one would have had,

seeing it in real life.

The focus system makes for another compositional

difference. Without autofocus, we must

focus and frame every shot in a slow, deliberate manner. That forces us to think about each image, and

when we do, we again tend to make different decisions.

When photographing action with a rangefinder, the lens must

be set to a certain distance, and the photographer waits for a composition to

come together. When it does, he presses

the button, and gets the shot. One

shot. In that same period, an SLR

shooter might have captured fifty images but their feel would be distinctly

different. Here’s an example.

The SLR images focus on a single player, and a moment:

The Leica image captures a larger context, and a sense of place. You can see it's a college gymnasium, and you can sense the crowd. None of that is present in the closeup, powerful as it may be in its own way.

As I said, each has its place. I create both kinds of images, depending on my mood and goals.

Without a sophisticated light meter (which can still be

wrong) we must manually evaluate every exposure setting. Each picture becomes the result of

deliberation and care. The image below is a good example:

The high performance SLR excels at capturing the moment, under any conditions. The rangefinder encourages careful, deliberate picture taking.

When we photograph people, our subjects often sense this

deliberation. They respond favorably to

the slow pace of rangefinder photography; often feeling and acting more

naturally.

The smaller size of a rangefinder also facilitates more

natural picture taking. People aren’t as

likely to feel intimidated by the smaller camera. There are streets you would not walk on with

a big SLR, where a nondescript rangefinder goes unnoticed and unremarked.

There are also places I won’t go with a full size SLR simply

because it’s big and heavy. My Leica can

accompany me to those places, because it’s small, light, and fits in a coat

pocket. Remember - the best camera is the

one you have when you need it. If you’re on foot all day it’s a lot more comfortable

to carry a Leica than a Nikon D4.

Weight and bulk excepted, some might say you could do the same things by using an SLR in manual mode. And indeed you could, for the most part. But people don't do that. When they buy a camera with automation, they use it. People do not buy automatic transmission cars to shift them manually, and cameras are the same.

With an SLR, one must take special steps to use it as a manual camera, where with a rangefinder it's the only way to shoot. The simpler tool forces the photographer to think, in ways a modern SLR does not. If you're shooting news, you probably don't want that as much as speed, performance, and reliability. But if you're shooting fine art . . . . that is the place of the Leica today.

By taking away the automation yet retaining such extraordinarily good image making capabilities the Leica forces you to become a better photographer. When your Leica images are less than tack sharp, overexposed, or clipped at one end of the other . . . there is no machine to blame. Just you. If you master a Leica you will take better photos with any camera. I guarantee it.

If I were looking to walk out into the desert, or to the top of a mountain, and photograph the landscape, there is no better camera I could carry than an M8, M9, or MP. If I wanted to capture birds or wildlife I'd make a different choice but for the scenery itself the Leica cannot be beat.

I also use the Leica to create action images (like the basketball shot above) that have a more classic, period feel to them. It's hard to put in words, but that b&w Leica shot certainly stands apart from any other photos of that particular game. In a world where so much looks the same, there's a lot to be said for that.

A farmhouse in the snow

John Sebastian of the Lovin Spoonful sings "Do You Believe In Magic?"

Radio City by night.

And remember - it's not a camera or a picture - but my third book Raising Cubby is coming, March 12, 2013. Be ready.

John Elder Robison

January, 2013(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on January 13, 2013 18:30

December 20, 2012

Aspergers and Violence - Let’s Stop the Rush To Judgment

Asperger’s, Autism, and Violence or Mass Murder

Let’s Stop the Rush To Judgment

Whenever something horrible happens the public and the media

look for answers . . . factoids to explain what may be truly inexplicable. Whatever

information can be discovered is tossed out into public view in the hope that

somehow a bunch of discrete facts and data points will somehow provide the

answers everyone is seeking.

This happens whether the event is a catastrophic fire, a

plane crash, or a mass killing. Thanks

to the Internet, people all over the world speculate about what happened and

why, often in the absence of any firsthand information. The result: a rush to judgment, and all too

often - innocent people harmed.

Sometimes these early speculations are prescient. When reporters observed an aviation mishap

and said, “the same thing happened on another flight a few years ago,” that

report led to the discovery of a flaw in an aircraft’s design, and the potential

saving of many lives when a design defect was corrected.

Unfortunately, on other occasions, early speculation proves

unfounded, wrong, or irrelevant. When

that happens, innocent people are often harmed by the rush to judgment. I’m very concerned that is occurring right

now, as the public digests news reports about the Sandy Hook school murders.

Reporters are saying the killer had Asperger’s Syndrome, a

form of autism. Every time a news story

does that – by tying “killer” and “Asperger’s” in the same sentence – they are

at some level implying that there is a connection between autism and mass

murder.

There’s not.

Statisticians have a phrase for this situation: Correlation does not imply causation.

Let me explain that by way of an example. Three banks are robbed, in three different

cities. Each bank had security cameras

trained on the entrances. In each case,

a review of the tapes showed a white Toyota Camry turning into the parking lot,

moments before the robbery.

Was that a clue? Was

the same car used to rob all three banks?

No. It was a random, irrelevant

coincidence. In fact, white Camrys are

one of the most common cars in the country and we might observe them at the

scene of most anything, without any causative connection at all.

How about this factoid:

Most school shooters are Caucasian males. You might find that statement a little more

shocking than the previous one. But it’s

true. Does that mean every white male

Caucasian who enters a school is a potential mass murderer? Of course not.

Suggesting a mass murderer had Asperger’s is much the same –

it may be true, but stating the fact does nothing to explain the crime, nor

does it help prevent other crimes in the future. What it does do – and this is important – is

paint a whole swath of population – Asperger people – with a brush that says

“potential mass murderer.”

That, folks, is a problem, because the average person does

not know enough about Asperger’s to know it does not turn people into mass

murderers. They file that factoid away

until the next time they see someone with Asperger’s. Then, instead of giving him a fair shake,

they treat him as a potential killer.

Everyone loses. As an adult with

Asperger’s, who’s seen enough discrimination already, I’m not too happy about

that.

What can we do?

There’s no way to “undo” a news story.

Going forward, perhaps the best thing we can do is explore

the question: Can Asperger’s turn a

person into a mass murderer? The simple

answer is no. Here are the reasons why:

Asperger’s is an autism spectrum disorder. People with Asperger’s typically have

difficulty reading the unspoken cues of other people. You might say we are oblivious to the

language of emotion.

Yet we are emotional people.

Many studies have shown folks with autism have very powerful emotions;

the problem is, we often can’t express those feelings in ways others can

recognize. Sometimes our responses seem

inappropriate (we may smile when you expect us to look sad.) Other times, an event that triggers a strong

emotional response in one person has no visible effect on a person with autism.

Lay people often take those signals to mean we Asperger

people don’t have feelings, or we don’t care about them, or that we lack

empathy. Nothing could be farther from

the truth.

As the definition of autism and Asperger’s says: This is a communication disorder. It’s not a

“lack of feeling” disorder. In fact,

most clinicians who work with people on the autism spectrum will tell you

autistic people tend to care deeply for people in their lives, and have a

sweetness; a childlike gentleness – something totally at odds with what you’d

expect in a cold blooded killer.

There is nothing in the definition of Asperger’s or autism

that would make a person think we are a violent group. That’s reinforced by criminal justice studies

telling us that people with autism are much less likely to commit violent

crimes than the average person. Indeed,

those studies show autistic people are far more likely to be victims of

violence than perpetrators.

If you’re looking for a group of people to fear, we’re not

it.

So where does that leave us, in our quest to understand

these most recent killings?

Adam Lanza may well have had Asperger’s. But that did not make him a killer. Some other factor was at work. Just as getting a cold doesn’t protect you

from catching measles, having an Asperger diagnosis does not mean you don’t

have a host of other issues as well. One

can suffer from homicidal rages, and also be diagnosed with Asperger’s. Those conditions are not mutually exclusive.

It's also worth noting the studies that have shown how

*anyone* may become violent, given the "right" (wrong) set of

circumstances. It's true that people on

the autism spectrum have less propensity for violence than the average person,

but that does not mean they can't ever become violent. If violence is a disease, no human is immune.

And that’s not the only possibility. There are plenty of other frightening and

disagreeable combinations in the world of psychiatry.

In fact, a child who grows up with a disability that leads

to bullying (like Asperger’s) may develop violent feelings toward his

tormenters. Most times, those feelings

stay inside, to the detriment of the victim.

Sometimes, though, the victims strike back. When that happens I’d say it was the

bullying, and not the disability, which turned that person violent.

One day we may have a hard medical test for autism –

including Asperger’s. Until then, it’s

diagnosed by observation – a process that is unfortunately more prone to error

than we would like. The Asperger

diagnosis attributed to Adam might even have been a mistake; sociopathy can

masquerade as mild autism or Asperger’s.

It’s easy to see how the two conditions might be

confused. After all, one is

characterized by a weak ability to show feelings, while the other is founded on

an absence of feeling within, and a lack of innate moral foundation. Those two conditions may look very similar,

but the outcomes are not. One leads to anxiety, depression, and social

failure. The other may lead to evil, and

a much darker place.

I’m not Adam’s therapist, and I have no knowledge of his

case, but I would not be surprised if there was quite a bit more to his

story. Much of it may never be known.

I wish I had some simple solutions to propose, so that we

might prevent these horrific crimes in the future. Unfortunately, I don’t. A reading of history shows us that most rampage

killers turned deadly with little or no warning. Many had no prior history of serious violence

and some had no criminal records at all.

Yet there are things we can do. We can take stronger steps to address

bullying, and we can offer counsel to those adults in greatest need. Many studies have shown that violence is a

last resort for people at the end of their rope. We have the power to give those people a

lifeline, so they won’t turn to the gun.

To me, this crime and others like it show the great need for

mental health reform. We have no

facility in this country for “mental health checkups,” and we’ve pitifully few

lifelines to help those on that slippery slope to suicide or murder, whatever

the cause. If I were to express a

Christmas wish here, it would be that our politicians see that failing, and

act.

Best wishes for the holiday season,

John Elder Robison

And remember - RAISING CUBBY is coming - March 12, 2013

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 20, 2012 04:14

Let’s Stop the Rush To Judgment - There's no connection between autism and mass murder

Asperger’s, Autism, and Mass Murder

Let’s Stop the Rush To Judgment

Whenever something horrible happens the public and the media

look for answers . . . factoids to explain what may be truly inexplicable. Whatever

information can be discovered is tossed out into public view in the hope that

somehow a bunch of discrete facts and data points will somehow provide the

answers everyone is seeking.

This happens whether the event is a catastrophic fire, a

plane crash, or a mass killing. Thanks

to the Internet, people all over the world speculate about what happened and

why, often in the absence of any firsthand information. The result: a rush to judgment, and all too

often - innocent people harmed.

Sometimes these early speculations are prescient. When reporters observed an aviation mishap

and said, “the same thing happened on another flight a few years ago,” that

report led to the discovery of a flaw in an aircraft’s design, and the potential

saving of many lives when a design defect was corrected.

Unfortunately, on other occasions, early speculation proves

unfounded, wrong, or irrelevant. When

that happens, innocent people are often harmed by the rush to judgment. I’m very concerned that is occurring right

now, as the public digests news reports about the Sandy Hook school murders.

Reporters are saying the killer had Asperger’s Syndrome, a

form of autism. Every time a news story

does that – by tying “killer” and “Asperger’s” in the same sentence – they are

at some level implying that there is a connection between autism and mass

murder.

There’s not.

Statisticians have a phrase for this situation: Correlation does not imply causation.

Let me explain that by way of an example. Three banks are robbed, in three different

cities. Each bank had security cameras

trained on the entrances. In each case,

a review of the tapes showed a white Toyota Camry turning into the parking lot,

moments before the robbery.

Was that a clue? Was

the same car used to rob all three banks?

No. It was a random, irrelevant

coincidence. In fact, white Camrys are

one of the most common cars in the country and we might observe them at the

scene of most anything, without any causative connection at all.

How about this factoid:

Most school shooters are Caucasian males. You might find that statement a little more

shocking than the previous one. But it’s

true. Does that mean every white male

Caucasian who enters a school is a potential mass murderer? Of course not.

Suggesting a mass murderer had Asperger’s is much the same –

it may be true, but stating the fact does nothing to explain the crime, nor

does it help prevent other crimes in the future. What it does do – and this is important – is

paint a whole swath of population – Asperger people – with a brush that says

“potential mass murderer.”

That, folks, is a problem, because the average person does

not know enough about Asperger’s to know it does not turn people into mass

murderers. They file that factoid away

until the next time they see someone with Asperger’s. Then, instead of giving him a fair shake,

they treat him as a potential killer.

Everyone loses. As an adult with

Asperger’s, who’s seen enough discrimination already, I’m not too happy about

that.

What can we do?

There’s no way to “undo” a news story.

Going forward, perhaps the best thing we can do is explore

the question: Can Asperger’s turn a

person into a mass murderer? The simple

answer is no. Here are the reasons why:

Asperger’s is an autism spectrum disorder. People with Asperger’s typically have

difficulty reading the unspoken cues of other people. You might say we are oblivious to the

language of emotion.

Yet we are emotional people.

Many studies have shown folks with autism have very powerful emotions;

the problem is, we often can’t express those feelings in ways others can

recognize. Sometimes our responses seem

inappropriate (we may smile when you expect us to look sad.) Other times, an event that triggers a strong

emotional response in one person has no visible effect on a person with autism.

Lay people often take those signals to mean we Asperger

people don’t have feelings, or we don’t care about them, or that we lack

empathy. Nothing could be farther from

the truth.

As the definition of autism and Asperger’s says: This is a communication disorder. It’s not a

“lack of feeling” disorder. In fact,

most clinicians who work with people on the autism spectrum will tell you

autistic people tend to care deeply for people in their lives, and have a

sweetness; a childlike gentleness – something totally at odds with what you’d

expect in a cold blooded killer.

There is nothing in the definition of Asperger’s or autism

that would make a person think we are a violent group. That’s reinforced by criminal justice studies

telling us that people with autism are much less likely to commit violent

crimes than the average person. Indeed,

those studies show autistic people are far more likely to be victims of

violence than perpetrators.

If you’re looking for a group of people to fear, we’re not

it.

So where does that leave us, in our quest to understand

these most recent killings?

Adam Lanza may well have had Asperger’s. But that did not make him a killer. Some other factor was at work. Just as getting a cold doesn’t protect you

from catching measles, having an Asperger diagnosis does not mean you don’t

have a host of other issues as well. One

can suffer from homicidal rages, and also be diagnosed with Asperger’s. Those conditions are not mutually exclusive.

It's also worth noting the studies that have shown how

*anyone* may become violent, given the "right" (wrong) set of

circumstances. It's true that people on

the autism spectrum have less propensity for violence than the average person,

but that does not mean they can't ever become violent. If violence is a disease, no human is immune.

And that’s not the only possibility. There are plenty of other frightening and

disagreeable combinations in the world of psychiatry.

In fact, a child who grows up with a disability that leads

to bullying (like Asperger’s) may develop violent feelings toward his

tormenters. Most times, those feelings

stay inside, to the detriment of the victim.

Sometimes, though, the victims strike back. When that happens I’d say it was the

bullying, and not the disability, which turned that person violent.

One day we may have a hard medical test for autism –

including Asperger’s. Until then, it’s

diagnosed by observation – a process that is unfortunately more prone to error

than we would like. The Asperger

diagnosis attributed to Adam might even have been a mistake; sociopathy can

masquerade as mild autism or Asperger’s.

It’s easy to see how the two conditions might be

confused. After all, one is

characterized by a weak ability to show feelings, while the other is founded on

an absence of feeling within, and a lack of innate moral foundation. Those two conditions may look very similar,

but the outcomes are not. One leads to anxiety, depression, and social

failure. The other may lead to evil, and

a much darker place.

I’m not Adam’s therapist, and I have no knowledge of his

case, but I would not be surprised if there was quite a bit more to his

story. Much of it may never be known.

I wish I had some simple solutions to propose, so that we

might prevent these horrific crimes in the future. Unfortunately, I don’t. A reading of history shows us that most rampage

killers turned deadly with little or no warning. Many had no prior history of serious violence

and some had no criminal records at all.

Yet there are things we can do. We can take stronger steps to address

bullying, and we can offer counsel to those adults in greatest need. Many studies have shown that violence is a

last resort for people at the end of their rope. We have the power to give those people a

lifeline, so they won’t turn to the gun.

To me, this crime and others like it show the great need for

mental health reform. We have no

facility in this country for “mental health checkups,” and we’ve pitifully few

lifelines to help those on that slippery slope to suicide or murder, whatever

the cause. If I were to express a

Christmas wish here, it would be that our politicians see that failing, and

act.

Best wishes for the holiday season,

John Elder Robison

And remember - RAISING CUBBY is coming - March 12, 2013

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 20, 2012 04:14

December 5, 2012

Autism - The Invisible Cord: A Siblings Diary

Last week, I wrote an essay challenging Time Magazine’s

choice of a title for its story on siblings of kids with autism. I believed calling the siblings “autism’s

invisible victims” was inappropriate and offensive.

The disgust I felt over the title choice overshadowed the

article itself, which made many good points if one could get past the

demonization and victimization.

The author of the story – a psychologist named Barbara Cain

– had previously written a book called Autism – The Invisible Cord: A Sibling’sDiary. I decided to download her book

and see how she described life as an autism sibling. I wondered what I would find.

I read the book in an hour, and all I can say is, what a

delight! It’s a sweet and gentle account

of Jenny and her life with Ezra, her autistic brother. There’s not a trace of victimization in the

book and indeed I recommend it highly to anyone who has a sibling living with

autism in their life.

Barbara’s story – told in the form of short diary entries –

really shows what is feels like to grow up with a brother who’s different – the

joy, the hurt, the desire to protect him and the hope he will grow up and make

a life on his own.

Reading her words, I thought of my own childhood, and that

of my son, who also has autism. If we’d

had sisters, would they have been like the Jen of the book? I hope so.

Kudos to Barbara for a wonderful story that any sibling or

family could treasure.

You can order her book here and find her @BarbaraSCain on Twitter

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 05, 2012 18:16

December 2, 2012

Are Siblings Really "Invisible Victims of Autism?"

What is a victim?

The word may be defined as: a living thing that is adversely

affected by the action of something else.

What does that make the “something else?” The victimizer.

Here are some appropriate examples that will be familiar to

all of you:

Bob was the victim of

a sophisticated swindle

The victim,

thirty-year-old Jessica Danes, was shot twice at close range

Don’t become another

burglary victim. Buy an Acme Alarm

today!

In every case the victimizer is someone undesirable. A swindler, a murderer, or a burglar. Indeed, the word victimizer has no positive

connotation in our society. It is not a

label anyone any reasonable person would want to wear.

With that preamble, here comes a headline from Time

Autism’s invisiblevictims – the siblings.

I was shocked to see such a phrase from a supposedly

progressive mainstream publication.

Left unsaid – but obvious – is the identity of the

victimizer. It is us! We autistic people are victimizing our poor

siblings. With everything else we’ve

done wrong growing up, victimization of our brothers and sisters is added to

our burden, thanks to this article. At

least, that’s how author Barbara Cain seems to see it.

It troubles me greatly when mental health professionals make

pronouncements like this, as if we autistic people are oblivious to what they

say or do. Siblings are not “victims of

autism.” They are siblings of autistic

people. Period. Some things about family life are easy. Other aspects are hard. Autism

is one of those things.

Does autism make life tough for us and our siblings? Sure it does, sometimes. Does autism show us a fun and funny side on

other occasions? Sure, it does that

too. Some of us revel in our

eccentricity while others would give anything to be rid of this autism

thing. All the while we have one thing

in common – we are not victims or victimizers.

We are just autistic people. Our

siblings aren’t victims either. They are

our brothers and sisters, sharing in life’s joys and struggles.

Autism is a permanent state of being. It’s how we’ve been as long as we can

remember, and how we will be – for the foreseeable future. We will change, grow and develop, but we will

always be autistic. Victimhood – in

comparison – is a temporary state. We

may become victims at any time – of a robbery, a building collapse, or an

Internet scammer. But those things will

pass. They do not define who we are in

the way an essential difference like autism does.

Some may defend this article by saying autism affects

everyone in a family negatively, like poverty or a hurricane might. That’s a flawed defense, though, because

hurricanes or poverty are faceless victimizers.

Anyone can blame them, but its meaningless because they are no one. We autistics, on the other hand, are

people. Real people. Your brothers and sisters. With that fact in mind I repeat – we are not

victimizers.

Many in our community have argued against the demonization

of autism and autistic people. It’s

distressing to see the same tired phrases repeated in a national forum like Time. I’m sure the writer had good intentions, but

the implementation leaves much to be desired.

Does that mean we should ignore the pain of autism

siblings? Of course not. Those of you who follow my writing and my

service on the IACC and autism science boards know that I have a strong

commitment to develop ways to relieve suffering and disability caused by

autism. It’s natural to think these

therapies, tools, or treatments would be aimed at the autistic people

themselves but in fact we must help everyone in the “autism circle.” That certainly includes the parents, and yes,

the siblings.

We must also change our world to be more accepting and

accommodating of autistic people. That

will reduce suffering for all of us.

Meanwhile, let’s keep the word “victim” out of the autism

conversation.

Best wishes to all of you this holiday season.

John Elder Robison

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on December 02, 2012 08:58

November 13, 2012

KIRKUS REVIEWS on RAISING CUBBY

KIRKUS REVIEWS weighs in on RAISING CUBBY:

A father reflects on the “tumultuous father-son journey” that he and his son have shared.

In this alternately funny and moving memoir, a follow-up to his 2007 best-seller, Look Me in the Eye, Rob

ison (Be Different: My Adventure's with Asperger's and My Advice for Fellow Aspergian's, Teachers and Misfits, Families and Teachers, 2012, etc.) discusses how he dealt with the joys and challenges of fatherhood. As he relates, these were exacerbated by his own social inadequacies and those of his son, both of whom are Aspergian and suffer from “blindness to the nonverbal signals of others.” The author reveals his thought processes as he struggled to share his painfully arrived-at social insights with his son in order to help him navigate a fulfilling life. Though his early life was rocky, Robison became a successful electrical engineer. Although he had not completed high school, he worked on sound and lighting effects for Kiss and other top rock bands of the 1970s. Later, he designed computer games before opening his own business restoring and servicing high-end European cars. When his son was born in 1990, fatherhood proved to be more of a challenge. Beginning with his efforts to understand why his baby was crying, he describes the trial-and-error problem-solving approach that he used to compensate for his inability to intuit social signals. In 2007, his 17-year-old son, who had a basement chemistry lab, was arrested for “possessing explosives with intent to harm people or property.” Although he was ultimately exonerated, Robison believes that targeting his son was an example of political grandstanding by the prosecution and a failure of the justice system.

A warmhearted, appealing account by a masterful storyteller.

http://www.johnrobison.com/

In bookstores everywhere March 12

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on November 13, 2012 02:45

November 3, 2012

Guest blog - Asperger's and Sibling Rivalry

Today's blog is a guest post from another writer, Trish Thorpe:

My name is Trish Thorpe. I am a

53-year-old woman with an older brother (by two years) who has Aspergers

Syndrome. He wasn't diagnosed until a couple of years ago. Once he was

diagnosed, I understood, finally, the role that my parents played in the years

of misunderstood isolation that he has endured, along with my own misunderstood

self-blame. The text below attempts to shed some light on the importance of

educated parenting, Aspergers, and sibling rivalry.

This post is directed to all the parents out there who struggle daily

to maintain peace at home between their Aspergers Syndrome (AS) children and

their neurotypical children. My goal

here is to provide a comparison between today’s awareness of Aspergers and

sibling rivalry and my own unfortunate past predicament. I also hope to

illuminate the importance of appropriate parenting in Aspergers families.

Thankfully, there is a lot of very insightful information available today

about how to recognize and deal effectively with Aspergers and sibling rivalry—something

that was desperately lacking while I was growing up.

After reading through several online resources, I can conclude that

the non-AS (or neurotypical) child who has an AS sibling needs extra help with:

·

Dealing

with peer and community reactions

·

Understanding

their sibling’s limitations

·

Having

their expectations clarified

·

Having

their feelings validated

The way that each parent provides for their own children’s needs of

course varies greatly. And needless to

say, not every strategy works in every situation. But the fact that you as a

parent are aware of the situation and are attempting to do right your kids, in

my mind, goes a long way.

Many of the online comments I’ve read are from frustrated parents who

have learned, tried, and failed using various techniques to improve their

family’s well-being. To them I say that it may not seem like it at the time, as

your children continue to bicker vehemently or display violent meltdowns even

after you’ve exhausted every strategy you’ve learned to intervene appropriately,

but believe me, your efforts count.

My own story is different from any of the scenarios that I’ve read so

far. One of my parents (my Dad) actually

initiated and perpetuated the sibling rivalry between me and my AS older brother.

He was constantly calling attention to the differences in our abilities and

playing us against each other. And even though Aspergers was not a recognized

diagnosis while I was growing up (1960s and 1970s), understanding and acknowledging

that there was indeed a problem seems like it should have been the appropriate

parental response.

There are three siblings in my family and I’m in the middle. I have an

older brother by two years who has Aspergers Syndrome and a neurotypical

younger sister who is younger than my brother and me by five years. I was the

athlete of the family (good at everything I tried, including schoolwork, and making

friends) and my older brother was the tinkerer (“a machine aficionado” in John

Robison’s words) and loner. Our Dad was horribly self-absorbed. Here are some

telling images:

[image error] [image error] [image error]

Here are a few paragraphs that describe a typical event from my past.

To set the scene, my family and I were staying at a hotel in Southern

California and my brother (Spencer), Dad, and I (“Fisheye” is my nickname) were

playing shuffleboard. With his typically wretched disdain for my brother’s lack

of athletic abilities, Dad blasted him verbally and used me as his benchmark:

Dad let Spencer push his shuffleboard disc first. Spencer pushed his

disc way beyond the tip of the triangle, so his score was zero. I got to go

next. I aimed my disc carefully toward the top section of the triangle.

“Good score, Fisheye! You got twenty points on that one!”

Dad’s turn. His disc slid perfectly and stopped right in the middle of

the top section of the triangle.

Spencer went next. Again he pushed his disc way too hard past the tip

of the triangle. Dad’s twitch was going really fast now. He stood still and

glared at Spencer.

In a harsh voice, he said, “Spencer, you’re a pig! You’re not even

trying! If you focused on the game and not the snack bar for once, you might be

as good as your sister!”

I tried to detect humor in Dad’s eyes. Maybe he was joking. But the

rest of his face looked serious and his tic was activated, so I guessed he

wasn’t kidding. I immediately put my head down, hoping no one else heard Dad’s

words. I must have done something terribly wrong for him to say such mean words

to Spencer. The three of us silently put our shuffleboard poles back in the

game shed.

You’ll notice from the excerpt above that the non-AS sibling has a

tendency to automatically assign self-blame for her brother’s lack of

athleticism (self-blame seems to be a recurring theme for neurotypical

siblings). Needless to say, when one of the parents fuels (or initiates) the

fire, a bad situation can only get worse.

My book (“Fisheye”) chronicles the long-lasting effects of bad

parenting on Asperger siblings. Writing through some of the memories of worrying

about my brother and blaming myself for his situation helped me a lot. I hadn’t

realized what an enormous impact my Dad’s (cruel and uneducated) campaign to

pit my brother and me against each other had. I realize now how my past feelings

have affected everything I’ve done during the past 35 years of my life and how

it affects my actions today, even though I’m much more aware of it.

So to the parents out there who are trying so desperately to be educated

and sensitive to the needs of both their

AS and non-AS children, keep on! Take comfort in knowing that your efforts

might feel futile, but the fact that you’re clued-in counts for a lot.

-

Trish

Thorpe

“Fisheye: A Memoir” http://www.amazon.com/Fisheye-A-Memoir-Trish-Thorpe/dp/0985328800

Bibliography:

My

Aspergers Child

Parenting

Aspergers Community

Aspergers

Advice

Circle

of Friends

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

My name is Trish Thorpe. I am a

53-year-old woman with an older brother (by two years) who has Aspergers

Syndrome. He wasn't diagnosed until a couple of years ago. Once he was

diagnosed, I understood, finally, the role that my parents played in the years

of misunderstood isolation that he has endured, along with my own misunderstood

self-blame. The text below attempts to shed some light on the importance of

educated parenting, Aspergers, and sibling rivalry.

This post is directed to all the parents out there who struggle daily

to maintain peace at home between their Aspergers Syndrome (AS) children and

their neurotypical children. My goal

here is to provide a comparison between today’s awareness of Aspergers and

sibling rivalry and my own unfortunate past predicament. I also hope to

illuminate the importance of appropriate parenting in Aspergers families.

Thankfully, there is a lot of very insightful information available today

about how to recognize and deal effectively with Aspergers and sibling rivalry—something

that was desperately lacking while I was growing up.

After reading through several online resources, I can conclude that

the non-AS (or neurotypical) child who has an AS sibling needs extra help with:

·

Dealing

with peer and community reactions

·

Understanding

their sibling’s limitations

·

Having

their expectations clarified

·

Having

their feelings validated

The way that each parent provides for their own children’s needs of

course varies greatly. And needless to

say, not every strategy works in every situation. But the fact that you as a

parent are aware of the situation and are attempting to do right your kids, in

my mind, goes a long way.

Many of the online comments I’ve read are from frustrated parents who

have learned, tried, and failed using various techniques to improve their

family’s well-being. To them I say that it may not seem like it at the time, as

your children continue to bicker vehemently or display violent meltdowns even

after you’ve exhausted every strategy you’ve learned to intervene appropriately,

but believe me, your efforts count.

My own story is different from any of the scenarios that I’ve read so

far. One of my parents (my Dad) actually

initiated and perpetuated the sibling rivalry between me and my AS older brother.

He was constantly calling attention to the differences in our abilities and

playing us against each other. And even though Aspergers was not a recognized

diagnosis while I was growing up (1960s and 1970s), understanding and acknowledging

that there was indeed a problem seems like it should have been the appropriate

parental response.

There are three siblings in my family and I’m in the middle. I have an

older brother by two years who has Aspergers Syndrome and a neurotypical

younger sister who is younger than my brother and me by five years. I was the

athlete of the family (good at everything I tried, including schoolwork, and making

friends) and my older brother was the tinkerer (“a machine aficionado” in John

Robison’s words) and loner. Our Dad was horribly self-absorbed. Here are some

telling images:

[image error] [image error] [image error]

Here are a few paragraphs that describe a typical event from my past.

To set the scene, my family and I were staying at a hotel in Southern

California and my brother (Spencer), Dad, and I (“Fisheye” is my nickname) were

playing shuffleboard. With his typically wretched disdain for my brother’s lack

of athletic abilities, Dad blasted him verbally and used me as his benchmark:

Dad let Spencer push his shuffleboard disc first. Spencer pushed his

disc way beyond the tip of the triangle, so his score was zero. I got to go

next. I aimed my disc carefully toward the top section of the triangle.

“Good score, Fisheye! You got twenty points on that one!”

Dad’s turn. His disc slid perfectly and stopped right in the middle of

the top section of the triangle.

Spencer went next. Again he pushed his disc way too hard past the tip

of the triangle. Dad’s twitch was going really fast now. He stood still and

glared at Spencer.

In a harsh voice, he said, “Spencer, you’re a pig! You’re not even

trying! If you focused on the game and not the snack bar for once, you might be

as good as your sister!”

I tried to detect humor in Dad’s eyes. Maybe he was joking. But the

rest of his face looked serious and his tic was activated, so I guessed he

wasn’t kidding. I immediately put my head down, hoping no one else heard Dad’s

words. I must have done something terribly wrong for him to say such mean words

to Spencer. The three of us silently put our shuffleboard poles back in the

game shed.

You’ll notice from the excerpt above that the non-AS sibling has a

tendency to automatically assign self-blame for her brother’s lack of

athleticism (self-blame seems to be a recurring theme for neurotypical

siblings). Needless to say, when one of the parents fuels (or initiates) the

fire, a bad situation can only get worse.

My book (“Fisheye”) chronicles the long-lasting effects of bad

parenting on Asperger siblings. Writing through some of the memories of worrying

about my brother and blaming myself for his situation helped me a lot. I hadn’t

realized what an enormous impact my Dad’s (cruel and uneducated) campaign to

pit my brother and me against each other had. I realize now how my past feelings

have affected everything I’ve done during the past 35 years of my life and how

it affects my actions today, even though I’m much more aware of it.

So to the parents out there who are trying so desperately to be educated

and sensitive to the needs of both their

AS and non-AS children, keep on! Take comfort in knowing that your efforts

might feel futile, but the fact that you’re clued-in counts for a lot.

-

Trish

Thorpe

“Fisheye: A Memoir” http://www.amazon.com/Fisheye-A-Memoir-Trish-Thorpe/dp/0985328800

Bibliography:

My

Aspergers Child

Parenting

Aspergers Community

Aspergers

Advice

Circle

of Friends

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on November 03, 2012 05:36

October 31, 2012

New York Magazine and the autism spectrum

New York Magazine takes on Asperger's and the autism spectrum. Enlightening? Offensive? A not-too-surprising view of how the rest of the world sees "us?" Let me know what you think . . .

http://nymag.com/news/features/autism-spectrum-2012-11/(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

http://nymag.com/news/features/autism-spectrum-2012-11/(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on October 31, 2012 05:49

October 13, 2012

A Modest Proposal for Autistic Employment

One of the toughest issues for adults with autism is chronic

unemployment. A fortunate few of us are

able to work independently without supports or subsidies, but a terribly high

percentage remain unemployed or underemployed, year after year.

All too often I hear of autistic geniuses – people with IQs

of 150 or even higher – bagging groceries or sweeping floors because they could

not navigate the social minefields of school and work. It’s only by the grace of god that I am not

one of those people. Smart as folks say

I am, I failed miserably in the social environment of every job I had. That’s despite my technical competence.

I see some of those same problems with other autistic adults

who can’t get jobs at all, or get fired from every job they get, until they end

up on social security disability, frustrated and cut off from the working

world. The same thing would have happened to me, if I

had not had the good fortune to start a small business that succeeded.

It’s the lucky few of us who remain productively

employed. Many of us stay that way by

the slimmest of margins. Some of us

succeed by finding tolerant or accommodating employers, and work we can do. Others (like me) forsake traditional jobs to

work for ourselves. If we can meet the

market’s demands, we prosper despite our eccentricities or even better -

because of them.

The problem is, most disabled people aren’t very successful

at employment, despite their best intentions, training, and unique skills. In the autism community chronic unemployment

and underemployment are one of our biggest challenges. We talk about all manner of solutions, but

ultimately, it comes down to this:

If we cannot do a given job as well – and as cost

effectively - as someone who doesn’t have a disability, we are not going to get

hired. Actually, the bar is really

higher. As outsiders in the world of

employment we need to be both better and cheaper to earn a place in the

workforce. Being equal is only good

enough once you’re inside.

We’ve tried solving the employment problem several ways in

America, with limited success. One way

or another, we run afoul of labor laws and regulations. For example, other countries allow the

creation of companies who employ autistic people (as an example) to do software

testing. In the United States that would

be discriminatory, and they’d have to allow anyone to apply for those jobs,

autistic or not.

Other countries allow companies to pay disabled people less

than the minimum wage, or less than the market rate for a given task. In the US, labor activists attack those sorts

of programs as exploitive. They paint

the employers as villains who are taking advantage of a disabled population.

The result:

Unemployment remains distressingly high among our disabled and different

population. Yet we remain eager to

contribute, and willing to work if only there is a place where we are wanted,

needed, respected, and able to earn a fair wage doing meaningful work. Something needs to be done.

I’d like to advance a modest proposal for how we might solve

the employment problem, by giving people with disabilities special employment

status, and awarding tax credits on a sliding scale to companies who hire us.

I call this Workforce Disability Credit, or WDC.

What if we allowed people to apply for WDC instead of or in

addition to social security disability?

When applying, a person would pass a similar functional evaluation, but

instead of being awarded a support check, that person would get a rating that

he’d take to employers.

He might get a standard disability check until he found work

under WDC, at which time his disability check would taper off or vanish to be

replaced by a larger check from the employer.

No one would be forced to join WDC, but those who wanted to

participate would have a subsidized path out of disability; something we cannot

offer people today. It wouldn’t work for

everyone, but if it worked for some, it would be very worthwhile.

The person’s WDC rating would tell employers what sort of

tax credit they’d get for hiring him (or her), to offset the added burden their

disability might place on the company.

For example, a mildly disabled person might have a 30% rating, meaning

the company would get a 30% credit for hiring him.

If they took a job that paid a nominal $20 per hour, the

employer could pay the disabled person the $20 hourly wage and get 30% back as

a tax credit. Hiring a person with a 60%

rating would get them 60% credit. The

worker would earn a market rate wage, and the employer would get a discount to

make someone who might otherwise be less productive or more costly attractive.

If we tied that program to a tax credit program for creating

jobs in America instead of exporting them to lower-wage nations, the effect

would be even greater.

In one stroke, such a system would make mildly disabled

people more attractive to employers and it would encourage them to seek work

with the goal of eventually getting off disability entirely.

A system like this would accomplish several important

things:

1 – It would bring jobs that have been outsourced overseas

back to America when disabled people can do them effectively and efficiently,

and American companies could take advantage of the tax credit to lower their

costs.

2 – It would be tremendously beneficial to the self-esteem

and well being of participants, by getting them off disability and into the

productive workforce.

3 – It would be a far better use of government dollars. Money paid out in disability support does

nothing for the economy. Money paid out

in employment subsidy builds the economy by building business.

4 – It would create incentives for American businesses to

find ways to employ our more disabled population in productive

occupations. Today most of those people

are unemployed with no real chance of sustained employment.

Some will say we have systems like this already, such as the

existing tax credits to hire disabled veterans, and various state programs to

hire people on support. However, I

propose two important differences:

1 – Give employers the tax credit right away, by deducting

it from the weekly payroll tax deposit.

The present system, where an employer gets a tax credit the following

April 15 when he files a return simply does not incentivize small businesses

where cash is tight. Furthermore, tying

the tax credit to income tax effectively restricts the credit to businesses

that make good profits – something that’s kind of rare among small business

today.

2 – Make the credit something the employees apply for, so

they can use it as an arrow in their quivers in the application process. All too often, the credits we have today

don’t get used because they are too complex, not well understood, and pay off

too far in the future.

We can’t expect a local landscaper to hire three disabled

guys in the summer, pay them all season, and then wait to get his $50,000

credit from the government next April.

And he won’t even get the whole fifty grand, if he doesn’t owe fifty in

taxes. How does he feel? Simple - he won’t do it. He will hire non-disabled workers and get his

benefits in productivity and billings right now.

The present credit systems, which overlook that essential

truth, are non-starters for those reasons.

The WDC might be capped at a certain dollar figure, and

participants in the program might have their disability rating re-evaluated

every few years. It’s quite possible

that many less disabled participants would work their way out of the program

and end up as regular market rate employees.

Those who remained disabled would continue to qualify for subsidy,

thereby remaining attractive to their employers indefinitely.

What do you think of this plan? Could it work? Would people embrace it? Is it even remotely possible, given where our

country is now?

I await your thoughts

John Elder Robison

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on October 13, 2012 08:23

September 27, 2012

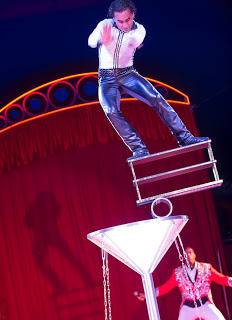

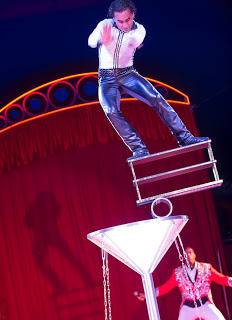

A Day at the Circus

I have always loved the circus. For the past fifteen years I've had the privilege of photographing the Hanneford Circus at the Big E Fair in West Springfield, MA.

The circus has the same name every year, but the cast of stars is ever changing.

West Springfield's Big E is one of North America's leading fairs, and they attract the top talent in the business year after year. Here are a few scenes from this year's production:

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

The circus has the same name every year, but the cast of stars is ever changing.

West Springfield's Big E is one of North America's leading fairs, and they attract the top talent in the business year after year. Here are a few scenes from this year's production:

(c) 2007-2011 John Elder Robison

Published on September 27, 2012 08:06