David Crystal's Blog, page 2

April 30, 2016

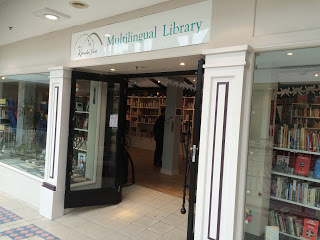

On a multilingual library

I was there because I'd agreed to become patron of the library, which was set up by the Kittiwake Trust and which opened last August. I gave a short talk about the need for libraries in general and for multilingual libraries in particular. I paste it below. It includes some of the points I made in an earlier post (January 2011) about the need to save libraries, and adds a summary of the research into the benefits of bilingualism. (For those especially interested in bilingual myths and realities, there's no better place than François Grosjean's blog, 'Life as a bilingual' .)

I paste below a couple of pictures Hilary took while we were there, which I hope hint at the scale of the project and the diversity it contains. They have books in over 60 languages so far, aimed at all ages. Many can be loaned out. Membership is a fiver a year - and for those who would find even that cost too much, they operate the beautiful 'pay it forward' system, where those who can afford it pay in advance for those who can't, such as people belonging to local refugee support groups. Parents with children are welcome to drop in, and there's plenty of space to sit, read, and play, That was one of the most noticeable things about the library: its welcoming, colourful, playful atmosphere. There's more than just books here. Artefacts from other cultures are sprinkled about, and I imagine these will grow as the project develops.

A particular delight was to see that the library doesn't restrict itself to language diversity but to dialect diversity as well. The Newcastle project has books on Tyneside dialects and other varieties of English, as well as local history - an important piece of PR, as many people unfortunately still can't see the point of bilingualism, but they begin to get an inkling when they realise that their own local dialect raises precisely the same issues of identity, pride, and cultural history.

The library is on the upper floor of the Eldon Garden shopping centre, in the centre of Newcastle. If you travel by car, the entrance is on the seventh floor. That sounds like a long way up, but from the inside it's just an escalator ride up, round the corner from John Lewis. Its phone number is 07776 684940. Its website is here , and it's on Facebook. So, if you're in or around Newcastle, my recommendation is to call in and become a member or a volunteer. And if you have any spare books in other languages taking up space at home, a donation is very welcome.

Why multilingual libraries matter

I spy, with my little eye, two words beginning with ... L.

It's a languages library.

L proves to be an interesting letter in English, because it introduces so many words strongly associated with the venture you have launched here: Literature. Languages. Living. Loving. Lending. Learning. Leisure. Legacy ...

How best to capture the spirit, the ethos, the value of libraries? Over the centuries, people have marvelled at them. They have been called a temple, a refuge, a second home, a leisure centre, a discovery channel, an advice bureau. It is a place where you can sit and draw the shelves around you like a warm cloak. When we gain a library we gain a source of wellbeing. The inscription over the door of the library at the ancient city of Thebes read (in classical Greek): 'The medicine chest of the soul'.

The lauding of libraries crosses centuries and cultures. First and foremost they are seen as repositories of knowledge, windows into history. 'A great library', said Canadian scientist George Mercer Dawson (1849-1901), 'contains the diary of the human race.' And especially when it is multilingual.

The metaphor of a library as a treasure trove is a recurrent figure. Let's bring together some famous personalities, and see what they have to say. Here is British poet and journalist John Alfred Langford (1823-1903): 'The only true equalisers in the world are books; the only treasure-house open to all comers is a library.' And Malcolm Forbes (1919-90), the publisher of Forbes magazine, is in no doubt about the appropriateness of the wealth metaphor: 'The richest person in the world - in fact all the riches in the world - couldn't provide you with anything like the endless, incredible loot available at your local library.' And this is writer Germaine Greer (1939- ): 'libraries are reservoirs of strength, grace and wit, reminders of order, calm and continuity, lakes of mental energy'. For Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) it transcends life itself: 'I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library'.

I like the reservoir metaphor - a library as a source of knowledge, waiting for us to simply turn on a tap. Like water, libraries are essential to our wellbeing, whatever our language background. As the American social reformer Henry Ward Beecher (1813-87) said, 'A library is not a luxury but one of the necessities of life.' It is a means of self-improvement, of advancement. Or, as poet and humorist Richard Armour (1906-89) put it in 1954:

Here is where people,

One frequently finds,

Lower their voice

And raise their minds.

And it brings together people from all walks of life.

Listen to the claim made by American cardinal Terence Cooke (1921-83): 'America's greatness is not only recorded in books, but it is also dependent upon each and every citizen being able to utilize public libraries.' Listen to American astronomer Carl Sagan:

'The library connects us with the insight and knowledge, painfully extracted from Nature, of the greatest minds that ever were, with the best teachers, drawn from the entire planet and from all our history, to instruct us without tiring, and to inspire us to make our own contribution to the collective knowledge of the human species. I think the health of our civilization, the depth of our awareness about the underpinnings of our culture and our concern for the future can all be tested by how well we support our libraries.'

Listen to science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov (1920-92):

'I received the fundamentals of my education in school, but that was not enough. My real education, the superstructure, the details, the true architecture, I got out of the public library. For an impoverished child whose family could not afford to buy books, the library was the open door to wonder and achievement, and I can never be sufficiently grateful that I had the wit to charge through that door and make the most of it.'

Have you noticed? I've just quoted from a Roman Catholic cardinal, a scientist, and a science fiction novelist. All sending out the same message. There can be few subjects like libraries to unite such disparate and distinguished minds.

As the British politician Augustine Birrell (1850-1933) once said: 'Libraries are not made; they grow.' That takes time. Behind each library, no matter how small, is a history of growth, watered by the professionalism of the library's caretakers and the enthusiasm of its readers. It is not an enterprise that can be measured by numbers. It is quality that counts, not quantity. No political body should fall into the trap of judging the success of a library solely in terms of the number of its visitors. That lone reader in the corner: who knows what personal potential will be realized in the future because of today's library experience? As American poet Archibald MacLeish (1892-1982) said: 'What is more important in a library than anything else - than everything else - is the fact that it exists.' If it exists, it will be used. And French writer Victor Hugo (1802-85) sums it up: 'A library implies an act of faith'.

And a multilingual library most of all, because of all the benefits that knowing more than one language can bring.

Bilingual benefits

It's normal to be bilingual. When we look around the globe, we find that three-quarters of the world’s population use at least two languages in their everyday lives, and half use at least three. Only a few nations - chiefly those who once had powerful colonies - have stayed monolingual. To be bilingual is the usual human condition.

You will still meet people who hold old-fashioned beliefs about bilingualism. You might hear somebody say that trying to speak more than one language will make your brain tired. Or that the two languages will get mixed up. Or that knowing two languages will slow you down when you're doing your schoolwork.

None of these beliefs are true. The brain has over 100 billion connections (called neurons) that it uses to receive, store, and send information. A language doesn't take up much of that brain space. People who speak languages like English and Spanish use only a few dozen sounds, a few thousand ways of making sentences, and a vocabulary of a few tens of thousand words. That might seem like a lot, but the brain handles it all easily. The evidence lies in the millions of people around the world who speak three, four, or five languages in their everyday lives without any trouble at all. And then there are the super-language-learners, who can handle twenty or thirty languages without their brain exploding. And anyone can be a super-language-learner. You just need a really good reason for learning each new language.

Many research studies have shown that learning more than one language is good for you - and learning lots of languages is especially good for you. Seven big pluses.

Being bilingual helps you to think more powerfully

Languages make people think in different ways. When you're speaking Spanish you think in one way; when you're speaking English you think in a different way. The mental exercise of moving from one language to the other makes your brain more active. It makes you more creative. It helps you solve problems more easily. And researchers have found out that being bilingual helps your brain to stay healthier when you grow old.

Being bilingual helps you to understand the world better

Language exists so that we can talk about the world to each other, and talk about ourselves and our feelings. Each language does this in its own way. The way Spanish talks about the world is different from the way English does. Every language, no matter how few speakers it has, tells us something unique about the way the world works. So, the more languages you know, the more you will come to understand what it is to be a human being on this planet.

Being bilingual helps you to feel proud of yourself

If you find yourself in a country where you don't speak the language, you're like a baby who can't talk. Learning another language, even to a limited level, removes the frustration of being unable to communicate when you find yourself in a place where it is spoken. You also feel you've really achieved something. You're right to feel proud of yourself, when you've learned another language.

Being bilingual helps you build friendships

We live in a world where a war can start because people have misunderstood each other. Learning each other's language can be an important step towards achieving cooperation among countries. Interpreters and translators are essential, but they can't replace the sense of mutual respect which comes from personal linguistic ability. Being able to speak someone else's language is the first step towards making them a friend.

Being bilingual stops you being scared of languages

The more languages you know, the more you come to understand how language works. You stop being frightened of languages and you find new languages easier to learn. You also become more aware of the characteristic features of your mother-tongue. English-speaking people often say they learned a lot about English grammar by seeing how it differs from other languages.

Being bilingual improves your social skills

Learning another language is to learn another culture and another way of behaving. As a result, bilingual people develop a broader range of social skills, and become more outward-looking. They are also likely to have a greater respect for the differences among cultures, and that can only be a good thing in a world where there is so much conflict.

Being bilingual can get you a better job

For most people, this is the best benefit of all. These days, many companies are international, and are looking out for people who can speak more than one language - and, even more important, who aren't frightened of learning new languages. These companies know they'll be more successful selling goods if they can do this in the language of the customer.

So, a multilingual library has a lot to celebrate. And perhaps at no better time than on the two big days of the year: Mother-tongue Day on 21 February and the European Day of Languages on 26 September. But the rest of the year too.

April 7, 2016

Further observations on the Hamlet H Quarto.

'How heavily hawked? Hope highly heeded Handschrift halfway hoodwinks whole host.' Professor David Denison

'Hugely hilarious - hope highly honoured.' Professor Michael Dobson

'Higher-order hypothesis hilarious! Here's hoping H Hamlet huge hit.' Jean Hegland ... whose novel, Still Time, incidentally, is a must-read for Shakespeare-lovers.

And from Professor Keith Johnson, who - in a post to the Shaksper website - introduces an issue that is now attracting considerable interest.

'David Crystal’s Unbelievable Hamlet Discovery hits on heavy and heretofore hidden hints about Hamlet’s history. Huge happenstance.

'Crystal’s H Quarto has implications for various areas of Shakespeare scholarship, including the field of Original Pronunciation, in which Crystal himself has been the guiding spirit. He has pointed out that in Early Modern English, an initial ‘h’ was often unpronounced. The first few lines of his H Quarto might then have read:

BARNARDO ’ark!

FRANCISCO ’o! ’enchman?

BARNARDO ’e.

FRANCISCO ’ey, ’our ’eedfully ’eeded.

BARNARDO ’orological ’alfnight’s ’appened. ’op ’ome.

'Taken as a whole, there seems no doubt that the H Quarto gives us the longest stretch of uninterrupted h-dropping in the entire canon of English literature, including in the works of Dickens, with all his various Cockney h-droppers.

'There is, however, more to the h-dropping than phonetic quirk. The following thoughts occurred to me a couple of days ago (it is today 3rd April). The hero’s name, and the play’s title, start with a dropped h, so would have been pronounced ’Amlet. There is, however, a little-known vowel change (known as the ‘Quite Small Vowel Shift’) that took place in just a few streets in Stratford-upon-Avon for a few months in the 1600 period. It is one of the few sound changes in English that took place retrospectively. In it, today’s vowel came to be pronounced as the one in hot. It was not ’Amlet at all, but ’Omlet.

'The word omelet first appeared in the language at around this period, and there is a little-known Elizabethan Cookbook entitled Chippes Withal (a title which, as it happens, the twentieth-century English playwright Arnold Wesker took for one of his plays). On the topic of omelets the book (written in verse) has this to say: Who wolde an omelette make, Perforce must egges brake. But this is just what the play previously known as Hamlet is about. In the process of becoming a fulfilled man, Hamlet creates mayhem. In culinary terms, eggs get broken.

'When Crystal next feels like a walk, one can only urge him to return to New House, and give his full attention to other broken drains. There may be other H Quartos to discover: The Happy Housewives of Henley, perhaps, and Hiems’ Homily (pronounced ’Iems ’Omily: the play about Leontes and ’ermione).'

It is entirely possible. And I suspect that the disturbed earth recently shown to be present in the radar scan of Shakespeare's grave is not an indication of a removed skull, as has been claimed, but of stolen manuscripts that were buried with the body.

Some scholars have sensed that Shakespeare's disorder was more deep-rooted than I claimed. Other letters may have been affected. This from Professor Tim Connell:

'And of course Love's Labours Lost bears out your theory, as does an early ms (doubtless amended by Condell and Heminge) of the Wicked Wives of Windsor.'

Peter Holland adds:

'David Crystal is to be congratulated on his remarkable discovery. I take it that the fact that the only non-h word I have identified is 'for' (p.76) is the consequence of its being the opening syllable of Fortinbras (the speaker of the stray word) and hence indicates Fortinbras' wish to hint at the otherwise unknown F quarto which would focus on Fortinbras' view of the whole narrative.

Or perhaps it's the long-surmised F quarto, known as the FQ. I recommend considering Midsummer Midnight's Musing too.'

Peter is to be congratulated on his close reading of the text. It is indeed the case that 'for' in the Fortinbras speech is the only instance of a non-h word, and I have long pondered the implications of this. There is some evidence that octolitteraphilia manifests itself in waves, and that, once a bout of h-activity has been released, normal letter usage resumes, temporarily. The fact that 'for' occurs at the very end of the play is indicative that this particular h-bout was about to run its course - presumably motivated by the new character name that was forming in Shakespeare's brain.

March 19, 2016

On HHamlet by PoD

Perhaps I shouldn't have been surprised. It took my website platform team (Librios), along with the printers (Clays of Suffolk), over a year to sort out the issues for The Unbelievable Hamlet Discovery. To begin with, there's a design issue to be solved. At the end of the day, the book has to look like any other printed book you'd see in a bookshop. So it has to go through the same stages of design and copy-editing and proof-reading as any other book submitted to a publisher. It has to have its ISBNs (plural, note, as printed book and ebook have to have different identifiers). Just because we (Hilary and I) are the publishers doesn't mean we can cut any corners. Fortunately we both have had plenty of editorial and design experience over the years. But it still needed a final look-through by a professional designer. And we learned an important fact: Clays are unable to PoD if a book is less than 80 pages.

A bigger problem, which took ages to sort out, is how to handle the postage. Once the book is given a price, the story isn't over. This is the biggest difference with buying a book at your local bookstore. The purchaser is typically going to buy just one copy, but the order can come in from any part of the world. This is what makes PoD so attractive to authors: their readership is worldwide. But how is the printer going to handle an order that comes in from the UK, or Germany, or Africa, or the USA...? The postage rates vary greatly. So all this has to be worked out so that orders can be processed automatically. Along with the further complications of VAT (where applicable).

Anyway, it's all sorted now, so if you order a copy, at www.davidcrystal.com, and pay via Paypal, it should arrive on your doorstep a couple of working days later. And those who prefer an e-copy will be able to do so directly, at the same site. (Here too there have been delays, as there are different design issues that have to be addressed.)

Actually, I would far rather have had the book published by a conventional publisher and sold in a conventional bookshop. I am very conscious of the need for authors to support the book-trade. So I would never self-publish without going down the usual publishing routes. I offered the Hamlet manuscript to two of my usual publishers and they turned it down - amazing, really, considering the significance of the discovery, but there we are. Similarly, when Hilary self-published her first children's novel, The Memors, it was only after we had explored possible publication with three houses. The only other books we self-publish are those in my backlist that are out-of-print, and where people are still interested in them.

Having said all that, we do find self-publishing an enormously exciting experience. We like being in control of all aspects of book production. Maybe, in another life, we would have been a publisher.

March 16, 2016

On an amazing Hamlet disovery, and other matters

The first, out on 24 March, is The Oxford Dictionary of Shakespearean Pronunciation - the result of a decade of work presenting all the words in the First Folio in OP (original pronunciation), along with the relevant evidence of rhymes and spellings. An associated website will have some extra material and an audio file, accessed by a special code that comes inside each copy of the book.

And then, on 1 April, The Amazing Hamlet Discovery - my finding in a Stratford garden of a hitherto unknown early quarto of Hamlet, showing conclusively that Shakespeare suffered from octolitteraphilia. A most moving document, published in its entirety for the first time. An oulipian experience.

November 20, 2015

On grammatical facts, fictions, and The Spectator

I’m not at all surprised my correspondent had a problem. The test asked readers to ‘give the parts of speech, including the grammatical part of any verbs, of “boiling” and every instance of “washing” in the sentence, “She is washing in boiling water yesterday’s washing in the washing machine that she uses for washing clothes”.’

Gwynne provided the answers in the letters column of the 7 November (I give his exact words):

Boiling: present participle (verb-adjective)

First ‘washing’: taken with ‘is’, continuous present tense, active voice and indicative mood. By itself, present participle.

Second ‘washing’: either gerund (verbal noun) or gerundive.

Third ‘washing’: noun acting as an adjective (‘noun-adjective’).

Fourth ‘washing’: gerund, acting both as a noun and as a transitive verb.

A letter in the issue of 14 November tells us that only 29 people attempted it and only one got the above answers. This didn’t surprise me either. I suspect most readers of the Spectator were sensible enough to see through the artificial nature of the exercise, with English being forced into the categories devised for Latin. Gerunds and gerundives have no place in an English grammar. And doubtless there were those, whose grammatical knowledge is better than Gwynne’s, who were marked wrong because they didn’t conform to Gwynne’s own misanalysis of ‘washing machine’. This, of course, is a compound noun - recognized as such in every dictionary - so the first element shouldn’t be classed as a separate part of speech at all.

Heaven knows how people are supposed to make sense of the jumble of terms in the answers. A present participle is a verb-adjective. One ‘washing’ is either a gerund, or a gerundive - though it can hardly be both at the same time. Another is apparently both a noun and an adjective. Another is both a noun and a verb. No wonder people are put off grammar when presented with this kind of thing.

Fortunately, modern approaches - as opposed to these resurrected Victorian ones - present English in a much more straightforward way. ‘Boiling’ is an adjective; ‘washing’ in ‘yesterday’s washing’ is a noun; ‘washing’ in ‘washing clothes’ is a verb; and so on. That is all that needs to be said, when first introducing word classes. Introducing imagined parallels - for instance, that ‘boiling’ is an adjective that reminds you of a verb - is an unnecessary confusion when identifying parts of speech.

Gwynne is so out of touch with what is actually happening in schools today. He says on his website that grammar ‘has by now been almost entirely abolished’. Tell that to Buckinghamshire teachers, with their splendid Grammar Project - to name just one of many initiatives taking place around the country. Yes, the kind of grammar presented in Gwynne’s Grammar has indeed been almost entirely abolished in schools, and that’s a very good thing. But it’s been replaced by an approach which respects English for what it is, and doesn’t try to treat it as if it were a bastardized form of Latin.

By the way, while I’m in this mood, I have a second piece of evidence to support my contention that the Spectator isn’t interested in facts. A few weeks earlier (24 October), a writer penned a travel piece on Anglesey, where I live, praising its natural splendour but denying that that there were any art galleries on the island, and saying it was impossible to go to an opera there. I wrote a letter pointing out that Llangefni has a fine art gallery, Oriel, with a stunning Tunnicliffe collection, and that the Ucheldre Centre in Holyhead has art exhibitions all year round. And Ucheldre regularly presents operas - Wales National Opera and Swansea City Opera, to name just two - as well as giving people the chance to see Covent Garden et al there too, thanks to streaming, at a fraction of the London prices.

They didn’t publish that one either. I think I'll stick to blogging.

October 30, 2015

On a one-word reaction to reports about drunken Aussie accents

That wasn't enough, it seemed. I then had to spend the best part of an hour doing my best to persuade the journalist, who had obviously fallen for this story hook, line and sinker, (a) that it had come from an Australian academic, Dean Frenkel, who, though described as a 'speech expert', doesn't seem to have any backround in the relevant disciplines of historical sociolingustics and phonetics (one web site describes him as a 'left field artist' among other things), (b) that it wasn't especially new - it turns up regularly, along with similar myths from other parts of the world (such as that the Liverpudilian accent is the result of fog in the Mersey, or the Welsh rising lilt is because they lived in the mountains, or that the Birmingham accent arose because people didn't open their mouths very much to avoid the dirty air), all equally rubbish, (c) that there isn't actually any evidence to show that convicts 200 years ago spoke drunkenly to their children on a regular basis, (d) that drunken speech actually has very little in common with the examples cited of the Australian accent, and (e) that if she examined those examples, she'd soon see that they don't support the case at all.

For instance, standing pronounced as stending is described as 'lazy'; but [e] is higher up in the mouth than [a], and actually takes more muscular energy to produce; it's the very opposite of lazy. The characteristic [ai] in words like day is similarly said to be the result of lazy drunkenness - in which case all Cockneys are drunk, for this diphthong is found in that accent too (among many others). (Cockney, along with some other British accents, is actually one of the real influencers of Australian pronunciation.) To call the accent a 'speech impediment' or the result of 'inferior brain functioning', as he's reported to have said, is absolutely extraordinary. On that basis every accent is an impediment - apart, of course, from the one Dean Frankel holds in his mind as some sort of speech ideal. It's the kind of thinking that was common in the early days of prescriptivism, and it's surprising to see it surfacing again now. And appalling that the media should so readily believe it.

Was my long conversation with the journalist worth it? Not in the slightest. When the article appeared, she quoted a couple of lines from me about the diversity of accents in the UK, and allowed the story to come across as if it were gospel. 'So if the Aussie accent is down to booze, why do other parts of the world speak English so differently?' The word 'rubbish' didn't appear at all. Nor the other word.

It's yet another example of how the tabloid media masquerades fiction as fact, in the interests of what they think is a good story. The Guardian, for example, ran a piece debunking the myth, but that will hardly have an impact on the many readers of the Mirror and the Daily Mail (which also ran the story prominently) who will have read it, believed it, and repeated it. It's really depressing. This kind of journalism makes the job of a linguist so much harder.

October 8, 2015

On the latest Lingo

I got to appreciate the scale of the problem a few years ago when I was writing A Little Book of Language, aimed at young teenagers. To check I'd got the level right, I had my first draft read by a 12-year-old. She gave me a right beating up! 'Underline any bit you find unclear', I told her. And she did. She drew my attention to words and content that I had never dreamt would cause a problem. For example, in my chapter on professional pseudonyms, I had included examples like John Wayne. She underlined John Wayne. When I asked her why, she said she'd never heard of him. I had to find different examples (eg Eminem).

I see the Lingo team will be at the Language Show in Olympia, London, 16-18 October (stand 804). Well worth a visit, I'd've thought, if you are in the area. But if you're not, I would recommend anyone who's involved with teaching language (or languages) to youngsters to take a look at Lingo. I don't normally use my blog to advertise things, but I have to make an exception in this case, as it's the kind of product I've long been hoping to see getting into schools. It's visible online at lingozine.com.

And now, back to a blogless life, caused by a killer project - a dictionary. There's nothing like dictionary compilation to take you away from the real world. It's not like any other kind of writing, where you are in control of your content. In a dictionary, the content controls you, in the form of the alphabet. The object in question will be out in March, The Oxford Dictionary of Shakespearean Pronunciation. It's at the copy-editing stage, and next month I have to record the audio version and soon after go through the proofs. Believe me, there's nothing more blog-destroying than a set of dictionary proofs.

July 28, 2015

On feeling closer, via Henry, to Shakespeare

But, to the play... The production displayed the dramatic possibilites of OP in all sorts of fresh and unexpected ways. OP, it needs to be remembered, is just a tool, as any other original practice, and its effect on a production needs to be judged in terms of the vision of the play as a whole. Ben adapted his innovative production to suit the intimacy of the Wanamaker playhouse. Not for this space the Olivier-style fortissimos of 'Once more...' and 'Crispin's day', but an exhausted muted appeal for the first and a quietly executed cameraderie for the second, with the OP underscoring these famous speeches to make them unexpectedly moving.

Nothing in the Shakespeare canon matches the stylistic variability in this play, and the company brought the OP to life in ways I'd never heard on stage before. At one extreme, there is the colloquial banter of the Eastcheap characters, with lots of elided sounds; at the other, the rounded and resonant tones of the bishops. And in between, we have Henry himself, who we know from Henry IV has the ability to code-switch - able to talk to tapsters in their own language as well as to match diplomats in their linguistic games. Henry also knows that kings set fashions - he says as much to Kate - so his OP reflects a formal style - for example, with word-initial h's pronounced - that the other English nobles emulate.

The military scenes demand a different set of OP choices. We hear the articulatory exaggerations of the Celtic captains, which add a novel comic dimension to OP, with an energetic Welsh r-trilling Welshman, an explosively palatal Irishman, and a comically incomprehensible Scot whose speech left the other captains baffled. Then, when Henry walks around the camp, the night before the battle, he stumbles across a group of soldiers (Williams et al) being told a story to keep their spirits up: in an ingenious addition, we hear the Rumour speech from Henry IV Part 2, told in a mesmerising OP by a Caribbean performance-poet who had joined Passion in Practice for the occasion.

Chorus is distributed around members of the company, displaying OP in a wide variety of accents, from Lithuania to California. People sometimes forget that OP is not a single accent, but a sound system that allows many accents - just as there are in Modern English today - and it is important to hear it in all its variation. From a dramatic point of view, the vocal diversity to my mind strengthens the role of Chorus as a universal observer.

Several other innovations inform this unusual production. The quarrel between Nym and Pistol has the two men shouting at each other with their speeches overlapping - a technique used to great effect after Duncan's murder in Ben's Macbeth at the Wanamaker last year. Henry's mind wanders as he listens to the Archbishop's interminable exposition about Salic Law, so at one point his speech fades into the background and we hear characters whispering lines into his ear from earlier history plays. Then there are the songs.

Songs in Henry V? Ben found five references to contemporary songs in the play in Ross Duffin's Shakespeare's Songbook, and located them at appropriate points. Hazel Askew researched them and taught them to the company. From my point of view, this was a first, as I'd never adapted OP for singing in a Shakespeare play before - least of all in Latin and French, as well as English.

The character of Boy (Falstaff's page) was developed to join the pantheon of Shakespeare's later-play Clowns. Ben drew our attention to the fact that Boy does something very unusual in this play: he talks directly to the audience, in quite long speeches - just as Clown would. He therefore had him introduce the play, as a sort of Chorus-Clown, by speaking the anticipatory epilogue at the end of Henry IV ('our humble author will continue the story, with Sir John in it, and make you merry with fair Katharine of France...'), leading directly into 'O for a Muse of fire...'. Boy-Clown is thereafter always around, hovering and observing, in the Eastcheap scenes. We see him killed, when left alone in the camp, and, in another innovative Ben Crystal twist, we see the dirty deed done by the Dolphin, disguised as Monsieur Le Fer.

The handling of the French OP was also a first. What surprised me here was its stylistic diversity, ranging from the lofty tones of the French King to the semi-French used by Henry when wooing Kate. In between, we have the genteel dialogue between Katherine and Alice, and the bonhomie among the French nobles, with the Dolphin in this production opting for a speech style as distinctive in its way as Pistol's. It proved quite difficult for me to develop a way of getting the actors to speak that sounded French yet avoided having them being pale imitations of Inspector Clouseau. My solution was to have them speak OP exactly as the English characters did, but with syllable-timing - the 'rat-a-tat' rhythm that is natural to French. This then allowed the Ambassadors and the Herald (Montjoy) - who in view of their calling would presumably have been more competent English speakers - to use an OP that was 'less French'.

All these choices resulted in an unprecedented kaleidoscope of OP - and revealed some new readings. For example, France is usually spelled France in the First Folio, but it is spelled Fraunce when the French are speaking (suggesting a pronunciation of 'frawnce'). Henry is also given this spelling when he is trying to speak French to Kate - and he has it just once when he is speaking English. At the point when Alice begins to interpret what Kate has said - that it isn't the fashion for ladies of 'Fraunce' to kiss - Henry interrupts with 'It is not a fashion for the maids in Fraunce to kiss before they are married, would she say?' The spelling suggests that he is mocking Alice's pronunciation. It's a tiny point, but it adds an extra nuance to the way Ben had this scene played, avoiding the lovey-dovey way it's often done, and underlining the fact that Kate is, after all, a political pawn. An interpretation where she is a reluctant player in the king's game, and where there is a great deal of tension in the room, seems wholly justified.

As with all OP productions, there were surprises on the opening night. I wasn't expecting Jamy to be quite so unintelligible, so the other captains were genuinely nonplussed, but the audience loved it. And the French nobles themselves decided that, when the Dolphin was praising his horse so fulsomely, there was sufficient closeness in OP between horse and arse to poke some extra fun at him. I never taught them that, but it worked!

Passion in Practice is a company devoted to recreating, as far as as is humanly possible, the work ethic of Shakespeare's company, cutting a play in the direction of 'two hours traffic', using cue-scripts, and not relying on weeks of rehearsal runs. It can be tricky when working in the Wanamaker, as - the space being so well-used - there is very limited opportunity for the actors to spend time there to see how to exploit it to best advantage. They had just the day before to explore the best ways of using the candles to point the night-time scenes and to implement one of the major insights of this production - the theme of shadows ('if we shadows have offended...'). Candles behind banners generated atmospheric silhouettes, creating the impression of many soldiers ('Into a thousand parts divide one man...'). Katherine did the whole of her English-learning scene behind a banner, as if in her boudoir, with the parts of her body displayed in silhouette ('the hand, the fingers...').

There was an opportunity on the day to 'top and tail' the scenes, so that the actors knew their entrances and exits; but the first time the company had the opportunity to present the play as a whole was when the audience was there. I was playing Fluellen, and after the battle there is a short scene where he talks to the king about them both being Welsh. The first time I had the chance to speak those lines to Henry and to hear how he would respond was during the performance. As I approached him verbosely ('Your grandfather of famous memory...'), he gave me a 'Oh no, not Fluellen going on and on again' reaction. It completely altered the way I then said the lines.

It must have been like this on the original Globe stage, with the actors surrounded by friends and family as well as the public at large. Not only did the audience not know what was going to happen next: the actors didn't either. Everyone was on their auditory toes, and the result must have been an electrifying freshness, which I sensed, at that moment, we were recreating with our OP production. It was the closest I've ever felt to Shakespeare.

June 21, 2015

On being a pedant with power

It would take a book to go through every point. Here is just one example of the bizarre and self-contradictory recommendations being reported.

Recommendation 1

'Read the great writers to improve your own prose – George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh, Jane Austen and George Eliot, Matthew Parris and Christopher Hitchens.'

Recommendation 2

The Lord Chancellor has told officials that they must not start a sentence with 'however'.

So, let's take a look...

However, they must obtain food from the outside world somehow. (Orwell, Animal Farm)

However, helped by the smooth words of Squealer, she assumes that she must have been wrong... (Orwell, Animal Farm)

It is her nature to give people the benefit of the doubt. However, Mr. Wickham's account seems to leave no doubt that Mr. Darcy is intentionally unkind. (Austen, Pride and Prejudice)

Mrs. Elton is disappointed. However, she decides not to put off her plans. (Austen, Emma)

Celia, now, plays very prettily, and is always ready to play. However, since Casaubon does not like it, you are all right. (Eliot, Middlemarch)

When I was a girl, I was more admired than if I had been so very pretty. However, she's reason to be grateful... (Eliot, Adam Bede)

Laugh? I should have bust my pants. However, they've fixed things up without that. (Waugh, Scoop)

However, it was cheaper than the Crillon, costing in fact only 17 francs a night. (Waugh, Decline and Fall)

However, a problem presented itself at once. (Hitchens, The Trial of Henry Kissinger) However, let us not repine. (Hitchens, Letters to a Young Contrarian)

I'll leave you to find examples in Matthew Parris - or, of course, in any modern writer.

Oh, and we mustn''t forget this one - one of several tracked down by the Independent journalist:

However, I was nudged out of my reverie by the reminder that it was indeed possible to send something through the post on Tuesday and be sure it arrived on Wednesday. (Gove, 2008)

It's linguistic hypocrisy. Do as I say, not as I do. It's usually not difficult to show how pedants use the very constructions they condemn, and normally one can quickly see through the hypocrisy and disregard them with impunity. But it's difficult when you're being paid by a pedant with political power. I pity the poor civil servants who have to waste their time (and taxpayers' money) trying to implement such unreal and eccentric prescriptions.

June 10, 2015

On becoming a language teacher

The Initial Teacher Training census from 2014 showed that 73 percent of language teacher trainees had a 2.1 degree or better; 20 percent had firsts. It seems to be a myth that only low achievers go in for language teaching. And the numbers are more than I thought: over 1100 postgraduate trainees were recruited last year. The NCTL say they are keen to recruit both new graduates and experienced industry professionals who are looking for a fresh challenge and may be open to a career change. And - another thing I didn't know - they say that if trainees specialise in teaching languages at secondary level, they could qualify for a tax-free bursary of up to £25,000 while training. There's more information about the training options here.

Their document mentions in passing that the number of children taking a language GCSE in 2014 was almost a fifth higher than in 2012. Several leading organizations, such as the British Academy and ALL (the Association for Language Learning), have over the past few years been emphasizing the importance of multilingualism. Is the message at last getting across, that learning a foreign language puts you in a really strong position in an increasingly competitive marketing world? I really hope so.

David Crystal's Blog

- David Crystal's profile

- 765 followers