Aly Monroe's Blog, page 8

July 30, 2011

The Perils of Research

One of the perils – or attractions of research – is being led off into something I did not know that has its own intrinsic interest.

Recently, purely for background, that may end up as a sentence in a finished book, I was looking into those who were not evacuated at Dunkirk but left 'in the bag' as the phrase was. This refers to the many thousands in the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) who spent the rest of the war in prisoner of war camps.

There is a youtube clip of the 51st Highland Division's victory march in Bremerhaven in May 1945, (click here) all drums and skirling bagpipes as they parade past Lieutenant General Sir Brian Horrocks. Many of these men had been prisoners of war only a short time before.

They have been overshadowed by what was made of Dunkirk, of course. What has been made of them – the forced winter march in early 1945 – has always stressed the heroic side of war.

These men deserved and deserve more.

Part of the reason I say this because I have only just learnt – perhaps I should have known before – that, according to my source, about 2,000 of the BEF 'went over' to the Germans in 1940. Naturally, this is not widely advertised.

I wonder however if any readers of this blog can point me towards more information on these men. What happened to them? Did any leave any accounts or diaries? I'd be grateful for any information on this.

July 19, 2011

Readers Get More Say.

Some of the pleasures of a) writing of a past just within living memory and b) growing old and/or being a grandmother are the cross-checks available – things and attitudes do change. Whether they improve or not is part of the fun.

For example, I bought a second hand edition of Vladimir Nabokov's letters in the Tottenham Court Road some years ago.

Among them is a short but indignant protest demanding that his name be removed from those advertised to appear at the Edinburgh Book Festival.

I don't know who was responsible for publicizing that Nabokov would appear without first consulting him – the impression remains, however, that over fifty years ago, one author at least thought that the notion of a Book Festival in itself was an absurd imposition on an ideally intimate relationship between reader and text. The text mattered more than the writer.

To pretend otherwise, I suspect, struck Nabokov as a sop to 'human interest' and all kinds of horrors like gossip and gawking. Nabokov's opinion of 'human interest' was not high; whose is right now? He was also rather down on those he considered 'hacks'. The meaning of words moves on too, in some cases, from noun to verb.

Of a similar age but different temperament, the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges put his attitude to the book-buying public another way. He claimed to find it difficult to conceive of a readership beyond the number 25. After that, things and faces started to blur and he was not sure who exactly was reading what he wrote.

These two writers have been dead for 34 and 25 years respectively. Hearing them speak now the time elapsed can seem longer. The surprise comes, I suppose, in their foreign but decidedly plummy English, and their confidence. Both only achieved fame relatively late in their lives.

We live in less confident times. Recently I spoke to a present-day writer, very shy but also very sharp-tongued, who complained that 'These days we are all so wretchedly chummy. Writers have become votaries to very entitled consumers.' He was really complaining that he spent so long 'going to book festivals and pretending to be nice.'

I didn't start publishing – I am certainly not famous – until late in my life. I am perhaps more grateful than confident as a consequence. And since my publicist, Lyndsey Ng of John Murray is presently trying to fix up some book festivals for me to attend around the publication of Icelight in October, I have to admit I have failed the Nabokov test. Abjectly.

There is something else however. The great Spanish painter Goya is famous for saying 'Aún aprendo' – I am still learning – when he was a very old exile in Bordeaux. I am not so old but I do like the feedback, even when it is not so complimentary, that book festivals provide. There is something quick and spontaneous about face to face meetings with people who have actually bought the words you have written. It's something I find very helpful – and enjoyable.

July 7, 2011

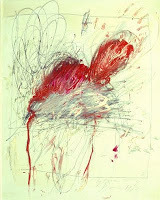

The Passage of Time: Picasso and Cy Twombly

The first time I actually heard someone say 'my five year old could do that' was in Cadiz, at an exhibition of Picasso etchings. At the time Picasso was, to some degree, being reintroduced into Spain. He had after all refused to allow his Guernica painting to return while Franco was still alive and the Franco regime had responded as might be expected, roughly 'Great painter, Bad Spaniard.'

There was some interest to see what had been missed. Evidently some visitors to that exhibition thought not a lot. Intrigued I looked at what they thought a five year old could do.

The etching was from a small group done in 1951 called La Partida, according to the notes inspired by a comic strip of Walter Scott's Ivanhoe. It is a medieval off to war and shows a knight on a horse, both in armour, accompanied by a page. Indeed the knight is more armour than person and the armour is vigorously rearranged into an absurd clank of pride and heraldry. The bit in the horse's mouth imposes a kind of equine grin.

I could go on, but hope I have indicated enough to say I have never met a five year old, however delightful, who could do anything even remotely similar.

Of course, children change. I note from the many comments made on the late Cy Twombly's work, that the phrase is now 'Any six year old could do that.'

June 29, 2011

Editing Reality

On Sunday mornings I zip through the online press, British, Spanish and American, pausing, of course, if an item catches my eye.

Sometimes this is a catch-up – I had previously missed, for example, that Patrick Leigh Fermor had died.

And then there are my regulars, writers I check up on to see what they are saying each week. One of these is Javier Marías in El Pais. Given the lead time – the article is in the supplement – there can be an air of relatively short term memory recovery about the piece.

On June 11 Marías tackled the respective briefings and leaks in an upcoming legal case involving a recent head of the IMF. His title, La Historia Doblemente Increible, hardly needs translation. That's doubly and that's incredible.

I should make it clear that Marías does not prejudge, does not take one side over the other in the conflicting stories , though his vocabulary choice when writing of the accused is not sympathetic to the man.

What he does bring is a novelist's eye to the stories being offered and points out how utterly unconvincing they both are.

There is Coleridge's famous line about 'the suspension of disbelief'. I'd guess that Marías is talking of the reports as such sensationally bad fiction that it is impossible to suspend any disbelief. An editor would be saying 'Doesn't add up' or 'Makes no sense' – though here we are talking of a future legal reality and judgement, and their preparatory public spin.

One of the reasons I like his books is because Javier Marías brings such respect and care to the craft of fiction. Good fiction brings a degree of inner logic and a convincing measure of observation and perception to an invention we can recognize or, if very novel, learn to recognize.

The only physical newspaper I now read is the weekend edition of the Financial Times. Last weekend Jan Dalley interviewed Philip Roth and asked him about 'the limits of fiction'. Mr Roth was not drawn.

June 9, 2011

Jorge Semprún – A country called Buchenwald

Jorge Semprún who died on June 7 has received praise from both his countries, namely Spain and France.

He had two countries because of certain events last century. Born to a well-off family in Madrid in 1923 he was out of the country when the Spanish Civil War started, his father being Ambassador for the Republic in The Hague.

As a result he was educated mostly in France and was there when the Germans invaded. He joined the resistance and was arrested by the Gestapo in 1943 at the age of twenty.

He was sent to Buchenwald, tattooed with the number 44.904 and experienced conditions that he would later say explained why he was not quite French and not quite Spanish. The camp destroyed all the certainties he had been brought up with and made him renegotiate his ideas of what living meant. What kept him going was his youth and the existence of a camp library, 'behind a fence, between two huts.'

On being liberated by two American-Jewish soldiers he returned to France. Spain was not an option.

In 1952 however he changed his name, or at least acquired papers and passport as one Federico Sanchez and joined the Communist Party in Spain. He was expelled in 1964, returned to being Jorge Semprún and living in France. By this time he had begun a wide-ranging career as a writer mostly in French.

As well as novels, memoirs and articles he wrote 15 film scripts including those for Costa Gavros' Z and Resnais' Stavisky.

Jorge Semprún's elegance had a lot to do with his integrity. This caused some delightful if doomed episodes. In 1988 the Spanish Government invited him to be Minister of Culture. He was reasonably effective – he negotiated the von Thyssen legacy – but fatally honest and unpartisan. He lasted three years before his public criticism of some corruption had him removed.

Once again he returned to France. I am not going to talk about his qualities as a writer –the films in particular have dated – but I don't think there are any doubts as to his qualities as a person. His experiences in Buchenwald made him espouse justice for others and to that he brought intelligence, charm and clear-eyed practicality.

June 1, 2011

Reading and Football

Yesterday I trotted along to a book swap run by the Edinburgh Book Shop at Henderson's in Hanover Street in Edinburgh.

The place was packed. There were two speakers: Sara Sheridan and Ian Rankin, who was kindly substituting for someone who hadn't been able to come. That's probably trading up but I don't know who the original speaker was.

The idea is that, over a glass of wine, people pass on books they have bought specially for the event, and receive another they would like to read. I gave a Judge Dee book by Robert van Gulik, and received David Mitchell's One Day. I'm not sure how many people had actually bought a book, rather than go their shelves.

Conversation was various but I particularly remember a chat about Barcelona FC. For those who don't know, Barcelona won the European Cup last Saturday and were rather impressive. Their trainer is the elegant Josep (Pep) Guardiola. He is a reader – not something closely associated with most football trainers in the United Kingdom. In Catalonia, as in other parts of Spain, it is traditional on April 23 to give someone a rose and a book.

I remember a footballer called Michel in Real Madrid saying that his greatest regret was that he had not studied as a boy and in consequence was the only member of the first team not have taken or be taking a degree.

Recently the Madrid version of Guardiola, the elegant, well-read Jorge Valdano (often referred to in Spain as the 'philosopher of football'), has lost out to the ex-trainer of Chelsea. Those who read Spanish can consult writer Javier Marias' articles for El Pais – there he gives vent to his disappointment that the club he grew up with has decided on a different tactic that he considers meaner, chippier and altogether less generous. It's not just about winning, but winning with great skill, honest manners and the kind of intelligence that values these attributes as much as just winning.

Romantic? I hope not.

May 28, 2011

In Praise Of Adaptability

My father loved books not only for their contents but also as objects. He loved the smell of new books. He could also love some productions that were so old the insects that had once lived in them were no more than stains – but the content, Erasmus' In Praise of Folly, or Bacon's Essays, for example, had to be strong enough to bear the ageing of the book. At one time he regularly used petals as book marks.

I never quite shared that enthusiasm for the book as an object, but yes, there are some beautiful, even sumptuous productions. One childhood favourite that I remember was a large illustrated edition of A Thousand and One Nights.

But when words alone are involved I only want something clear and clean to read.

Now, for my birthday, my very amiable children have given me a bottle of champagne – and a Kindle.

I have to say I love it. These days I like to set the size of the print. I've bought too many books with tiny print in the last few years. Often, if I'm using a reading lamp, I get a distracting shadow of the print on the next page behind the words I'm trying to pick out.

Now my reading can easily be held in one hand, is as clear as I like it and 'turning' a page dislodges no dust or paper scurf.

Reading about a book and downloading it within seconds is gratifyingly novel. Not having to use a book mark is also a sort of freedom.

Does the Kindle change the reading experience? I don't think it does, though I will say I am enjoying the re-arrangement of the experience.

I'd even say, so far at least, that it brings me into a more obviously direct contact with the point of a book, its contents. I find I get into the book more quickly – there are less preambles, no distracting cover. Just you and the writer.

May 9, 2011

A Landmark - Innit?

The news that innit has achieved the status of an acceptable Scrabble word made me pause this morning. Do I like it? Instinctively, no. Do I find its usage interesting? Definitely, yes. What is interesting about it is not so much that it has achieved recognition as a way of saying isn't it?, but that it also serves for doesn't it?, aren't we?, won't you? etc. In other words, it is the equivalent of the French n'est-ce pas?, the Spanish ¿verdad?, the German nicht wahr? and so on. In linguistic terms, surely a landmark moment?

For centuries, the English language has been undergoing a process of simplification – or if you like, streamlining. It's ancestor, Anglo Saxon, was a highly inflected language – with lots of different word endings to denote tense, person and grammatical case – quite similar in that respect to Latin or modern German. Gradually, most of these endings have been shrugged off, leaving a few remnants – such as the 's' in he/she plays as opposed to I/you/we/they play. English words today are a bit like plasticine – the same word, with no alterations or additions, can be used as a noun, a verb or an adjective, just by changing the order of the words in the sentence. This swackness, together with its part Latinate, part Anglo-Saxon origin vocabulary, as well as more recent imports from other languages, makes for a marvellous range of possibilities. It has been an evolutionary process and, as I have said elsewhere in this blog, I believe in evolution.

Will I begin to use innit? I don't think so. Am I in favour of encouraging children to speak correctly so that they can learn how to read more easily? Definitely.

At present, innit seems to be mainly used in the south of England by the young. Will it start to creep over boundaries and begin to be used more widely?

I will observe from a respectful distance and watch it flower or shrivel.

May 2, 2011

Lost Children, Lost Parents

A few days ago Ernesto Sabato died. He was 99 years old, just a couple of months short of his century. He trained as a physicist but turned away from science and became a novelist and essayist. His novel The Tunnel, written in the forties, is probably his most famous, praised by, amongst others, Albert Camus and Graham Greene.

An Argentinian, of Italian and Albanian extraction, he later became more famous for what is usually referred to as The Sabato Report – an examination of the atrocities committed by the military dictatorship that collapsed after The Falklands War – or the Malvinas, as the Argentinians call the islands. He described this task as 'a descent into hell', but with scrupulous attention to detail he and others enumerated and detailed what they could.

Most people have heard of 'los desaparecidos' - literally the disappeared or 'missing' -, a word used to describe those that vanished, that is were killed, during the dictatorship. But today I want to talk of the children of the 'disappeared'. They were often whisked away and adopted by 'more suitable' families. That is, families that supported the dictatorship.

In Argentina, events were so recent and raw that great efforts at reconciliation and examination were made to lay the dictatorship to rest. In Spain however a different approach was used. When Franco died in 1975 almost everybody was keen to move on, turn the page.

I am not recommending one approach or the other. The Argentinian dictatorship was relatively short and brutal. Franco's was much longer. Either way, casualties and injustices persist. Some of these injustices are finally being faced.

For the entirety of the Franco regime, children were removed from 'unsuitable' parents to be 're-educated'. As late as the early seventies sedated mothers gave birth to be told later the child had died and the body had already been disposed of. This was, with connivance of governmental and religious authorities, untrue. A month ago in a small town called Chiclana, near Cadiz, a meeting was held to inform those affected about the steps they should take to lodge a complaint with the investigating judge.

There are several hundred, possibly several thousand people in Spain, presently trying to establish contact with a child or parent. In Chiclana, and throughout the province of Cadiz, women of what the Spanish call humilde (humble) origin are coming to terms not just with the idea they were lied to, but also with trying to trace a person they thought was dead.

April 22, 2011

Easter Rice

Today may be Hot Cross Bun day, but on Viernes Santo (Good Friday) in Spain, it's traditional to eat Arroz con Leche (Rice with Milk). I have never liked rice pudding – really, not at all - but I was introduced to this when I lived in Cadiz and it is a totally different creature. There are many different versions, with different ratios of milk to rice and sugar, some with added egg yolks and some without. All have cinnamon as a star ingredient and can be eaten hot or cold.

The dish is supposed to be of Moorish origin (as are many Spanish recipes) - some versions include raisins and/or rose water, decorated with rose petals (no added egg yolks for this version) - but the version I like best was given to me by a friend from Malaga. It's made with lemon and cinnamon, and for me is much nicer cold. It's great for kids (makes a change from yoghourt), but it can also be used as a cool summer dessert, happily made in advance, when you have friends over. It looks good, too.

The following ingredients are approximate, depending on how liquid you like it and how sweet you like it. Slightly less rice to milk will be needed if you thicken with egg yolks:

Arroz con Leche

Ingredients

4 cups of full cream milk

¾ - 1 cup of round grain rice

Approx ¾ cup of white sugar (this depends on your taste – some recipes say as much as 1 ¼ cups)

The peeled rind of a small lemon (some recipes also include some orange peel)

A cinnamon stick.

To decorate: brown sugar mixed with powdered cinnamon (or rose petals, in the raisin and rose water version without egg yolks).

Method

Wash the rice and place in a saucepan together with the milk, the sugar, the lemon (and/or orange) rind and the cinnamon stick.

Cook gently over a low heat, stirring occasionally at first, increasing to constantly as the rice gradually cooks and absorbs the milk.

When it is practically cooked and becoming creamy, remove from the heat and leave to stand.

If preparing the raisin and rose water version, add these now, and remove the citrus peel and cinnamon stick. Pour into a dish/individual ramekins and decorate with rose petals

If preparing the lemon and egg yolk version, place three egg yolks in a cup. Stir well and mix in a little of the rice mixture, then add this to the pan and stir. Return to the heat (very low) and stir continuously until it becomes silky and thickened. Remove the pan from the heat and leave for approximately ten minutes. Take out the lemon rind and cinnamon stick and pour into a dish/ individual ramekins. Decorate with a mixture of brown sugar and cinnamon, sprinkled in a lattice across the surface.

Leave to chill – and eat.