Aly Monroe's Blog, page 3

May 29, 2013

Stiff Upper Lip

This Saturday (June 1) in Bristol, I will be taking part in two Crimefest panels. The first, with Tom Harper, John Lawton and William Ryan, will be moderated by Martin Walker and is called ‘The Cold War – An infiltrating chill.’ We have, visitors will be glad to know, already considered suggestions and possible developments. One of these is ‘Heroes and Anti-heroes’.

This set me thinking about the nature of heroism and its antithesis, and reminded me that I had once met an out and out hero of the traditional rather than Cold War sort. British, the subject of a book and a film in the nineteen fifties, he had been a one parliament MP (1959-1964) but, some years later, was looking unhappy at one end of bar.

His problem was, of course, that he had become a public hero and to some extent he had listened, to the extent anyway of finding out that he was not cut out to be an MP. By the time I met him, he had also worked out that the circumstances he had become famous for had little to do either with him or what had happened. As a result he felt a) fraudulent, b) that he no longer belonged to himself and c) that any future was, as he put in, ‘in hock to the past and a bloody film.’

The film still turns up on TV. You know the kind of thing. Stiff upper lip, calm in the face of overwhelming odds and the same plucky actors who so often died in these films for something bigger than themselves.

Although about an incident well after WW2, the film is not, like the much more famous and praised, Bridge over the River Kwai, almost wholly inaccurate, but was certainly put through the spin machine and emerged as part of the stiff upper lip myth and a hottish version of a Cold War stand-off.

I suppose the real point is that the hero above got no choice – British foreign policy of the time decided a hero was needed and he was, briefly, elevated and flattered, as an example of British spirit and patriotism.

I suspect that on Saturday we won’t be talking of this kind of hero – the Cold War was more about the publicity given to villains and traitors.

Published on May 29, 2013 03:02

May 13, 2013

My Mother

When your mother is 92 you can’t really be surprised that she should die. Surprised no, but shocked yes.

My mother died early in the evening of May 8. We had heard the day before that she had pneumonia in both lungs. She had three children and we all talked to her, my brother (in California) last, only a couple of hours before she died. My sister had already hot-footed it back from France where she had been on holiday and was coming up the stairs of the care home as she was dying. My mother had been listening to Handel’s Messiah and had put my father’s watch beside her.

I was teaching a course at the OU in Milton Keynes when I heard. I left immediately to be with my sister and prepare the funeral. Feeling the effects of abrupt rescheduling - as well as shock. Only I am not quite sure that ‘shock’ is the word. It’s certainly part of it but it’s also a sudden access to all that past.

My father died in 1989 at the age of seventy-one. My mother will join him in the same grave nearly twenty-four years on. A lot has happened since then, of course, but a death always causes a kind of compacted disorientation in those left and I’m including grandchildren who’ve married since and nine great-grandchildren who don’t know what has happened.

Now I do not normally write very personal blogs. But since I have been doing other things, I am pretty confident I have been remiss acknowledging the kindnesses shown me on publication of Black Bear on May 9. Apologies.

My mother was born just before Christmas in 1920, one of the many children of very long-lived Italians I always called Nonno and Nonna. She herself, when she became a grandparent, was known as Nonna.

She lived a long life and was very fortunate. That’s a cause for a celebration. But right now I’ll leave that for later. I am feeling slow and tired. It wasn’t until I was on the train leaving Milton Keynes that I realized I was going away from the Open University – where my mother took a degree at the age of 64. She hadn’t had the chance when growing up and she gave herself the opportunity as a retirement present.

Published on May 13, 2013 05:32

April 27, 2013

Meet the 'Real' Peter Cotton, Part 5 - the seeds of Black Bear -

It’s been some time since I wrote about the ‘real’ Peter Cotton. There is more to add. I am now able, for example, to say what his real name was – David Collingwood (1919-2011). And since he had a considerable amount to do with the subject of Black Bear, now about to be published, it is time I made his contribution clear.

As I have mentioned in other blog posts (collected together on my website - http://www.alymonroe.com/peter-cotton... Meet the Real Peter Cotton)I met him in 2005 when he had a house in Guadalajara in Spain. He was a widower, his second wife, Helen, had died the year before and the introduction was made by his step-daughter Caroline. I have also mentioned that I made about nine hours of recordings of what he had to say over several meetings.

What I haven’t mentioned is that he showed me various documents, ‘scraps’ he called them, ‘of the myths we are all subject to.’

One of these was an extraordinary document written by a G F Bakewell in 1947 ‘in light of the current interest in Human Rights.’ The ‘current interest’ was of course the United Nations Charter and the preparation of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). The ‘paper’ was quite long and was an entirely straight-faced attempt to suggest that the use of ‘so-called truth drugs could be construed as being in the spirit of Human Rights Legislation.’

The gist of G F Bakewell’s argument was that such drugs ‘could assist Intelligence Agencies obtain information from unwilling subjects without recourse to torture.’

David Collingwood laughed. It sounded perfectly genuine. I have said before he was rather old-fashioned and amiably patrician in manner but also something of a dramatic story-teller.

‘You see physical violence is so visible. Blood, the fragility of human bodies, distraught witnesses – the horror is obvious.’

I had just been doing voice-over work on a documentary about the Madrid bombings; indeed his step-daughter Caroline runs the studio where the voice-over was done.

‘Now imagine what it’s like to be punched in the brain. It’s a perfect match of physiological and psychological attack, certainly if you are unsuspecting.’

In an earlier blog I mentioned Mr Collingwood’s interest in the late Sir Peter Russell, called Peter Wheeler (his birth name) in some Javier Marias novels. Following a bad accident in WW2, Sir Peter was taken away and beaten up by his own side – ostensibly to help him should he face torture at the hands of the Nazis.

The point? British intelligence was not averse to treating its own quite as badly as any enemy would.

While writing Black Bear this aspect of historical reality led to some problems. My editor and publishers disliked the notion that Cotton’s superiors would have connived in what happened to him.

David Collingwood was in no doubt when considering his own case.

‘Christ, yes,’ he said. ‘They gave permission without my knowledge or much thought on their part.’

In 1947 the US Navy or Senior Service began Operation Chatter. They had dibs as it were on the new thinking as described by G F Bakewell. As a result, several thousand people, quite a few volunteers, were subjected to various drugs without understanding what they might experience or what risks they were taking.

David Collingwood said he received multiple doses of scopolamine, mescaline and sodium amytal. ‘Or at least that was what I was later told.’

‘Scopolamine is the “Devil’s Breath”, supposedly much used by criminals in Columbia. It comes from a rather pretty plant. Mescaline is peyote of course. Sodium Amytal was developed by the Germans. It really gets your heart rate up.’

The purpose? ‘Basically to see what happened when you pumped these things into a male of 28 in reasonably good health. It was a kind of jab and see. I assure you the British I saw after the experience were mostly interested a) in whether or not the drugs had rendered me impotent and b) whether I had suffered any hair loss. That was exactly the same as worries about radiation sickness.

‘The so-called experiments were to see whether there might be a magic key to unlocking someone’s mind. I never saw my results, though I was told I had been a useless subject. In any case, the obvious effects of each drug were pretty much established as far as intelligence was concerned. You got drunk-style rambling, acute memory loss – I still have no recall of what happened to me - and a tendency to hallucinate. Some of those experimented on never recovered. But the Operation continued, using different drugs in different doses, rather as if they were mixing shades of paint and they might strike it lucky and get Intelligence gold.’

‘The US Navy gave up in 1953 – and then the CIA took over. By that time, however, the drugs were being used as accompaniment to traditional interrogation techniques not as a substitute.

‘A year on I was given a medical. My blood pressure was still high and I was told my heart had probably been permanently affected and I shouldn’t expect a long life. The problem I experienced longest was what I called the see-saw. I’d suddenly get the impression the floor was tilting and I’d slide off. I’d move – but if I moved too far, the floor would start tilting the other way. That lasted until about 1950 and I got into the habit of adjusting my stance. Someone once asked me if I had been a long time at sea.’

‘Didn’t the British say anything else?’

‘No. Not really. Quite soon I realized it was being treated as a sort of joke. The Americans had pumped drugs into me and I had really suffered very few after-effects.

‘Oh,’ he added. ‘I did get to see a very slim report later in my career. The experience was described as a ‘crash course in realism and the benefits of self-reliance. The subject came through the trial well.’

We talked some more.

‘Intelligence services everywhere believe and want others to believe that they deal in much harsher realities than the people they are supposed to defend can bear. That’s what justifies their existence, usually in the claim that they must have the knowledge and capabilities to ward off an enemy as cruel and now as fanatical as can be imagined. I suppose there’s a valid point in there somewhere.’

‘Did you feel betrayed?’

He smiled. ‘It’s not that sort of business. I certainly didn’t imagine any other Intelligence service would behave better. People want to believe what they want to believe. They’ll change the facts. They’ll develop myths. But even there, all myths are a compromise between what you want to think and what is acceptable and attractive to others round you.’

Black Bear is of course fiction – but I thought truth drugs and the myths around them made for a particularly gruesome kind of violence: silent, bloodless, but truly hard to combat.

As I have mentioned in other blog posts (collected together on my website - http://www.alymonroe.com/peter-cotton... Meet the Real Peter Cotton)I met him in 2005 when he had a house in Guadalajara in Spain. He was a widower, his second wife, Helen, had died the year before and the introduction was made by his step-daughter Caroline. I have also mentioned that I made about nine hours of recordings of what he had to say over several meetings.

What I haven’t mentioned is that he showed me various documents, ‘scraps’ he called them, ‘of the myths we are all subject to.’

One of these was an extraordinary document written by a G F Bakewell in 1947 ‘in light of the current interest in Human Rights.’ The ‘current interest’ was of course the United Nations Charter and the preparation of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). The ‘paper’ was quite long and was an entirely straight-faced attempt to suggest that the use of ‘so-called truth drugs could be construed as being in the spirit of Human Rights Legislation.’

The gist of G F Bakewell’s argument was that such drugs ‘could assist Intelligence Agencies obtain information from unwilling subjects without recourse to torture.’

David Collingwood laughed. It sounded perfectly genuine. I have said before he was rather old-fashioned and amiably patrician in manner but also something of a dramatic story-teller.

‘You see physical violence is so visible. Blood, the fragility of human bodies, distraught witnesses – the horror is obvious.’

I had just been doing voice-over work on a documentary about the Madrid bombings; indeed his step-daughter Caroline runs the studio where the voice-over was done.

‘Now imagine what it’s like to be punched in the brain. It’s a perfect match of physiological and psychological attack, certainly if you are unsuspecting.’

In an earlier blog I mentioned Mr Collingwood’s interest in the late Sir Peter Russell, called Peter Wheeler (his birth name) in some Javier Marias novels. Following a bad accident in WW2, Sir Peter was taken away and beaten up by his own side – ostensibly to help him should he face torture at the hands of the Nazis.

The point? British intelligence was not averse to treating its own quite as badly as any enemy would.

While writing Black Bear this aspect of historical reality led to some problems. My editor and publishers disliked the notion that Cotton’s superiors would have connived in what happened to him.

David Collingwood was in no doubt when considering his own case.

‘Christ, yes,’ he said. ‘They gave permission without my knowledge or much thought on their part.’

In 1947 the US Navy or Senior Service began Operation Chatter. They had dibs as it were on the new thinking as described by G F Bakewell. As a result, several thousand people, quite a few volunteers, were subjected to various drugs without understanding what they might experience or what risks they were taking.

David Collingwood said he received multiple doses of scopolamine, mescaline and sodium amytal. ‘Or at least that was what I was later told.’

‘Scopolamine is the “Devil’s Breath”, supposedly much used by criminals in Columbia. It comes from a rather pretty plant. Mescaline is peyote of course. Sodium Amytal was developed by the Germans. It really gets your heart rate up.’

The purpose? ‘Basically to see what happened when you pumped these things into a male of 28 in reasonably good health. It was a kind of jab and see. I assure you the British I saw after the experience were mostly interested a) in whether or not the drugs had rendered me impotent and b) whether I had suffered any hair loss. That was exactly the same as worries about radiation sickness.

‘The so-called experiments were to see whether there might be a magic key to unlocking someone’s mind. I never saw my results, though I was told I had been a useless subject. In any case, the obvious effects of each drug were pretty much established as far as intelligence was concerned. You got drunk-style rambling, acute memory loss – I still have no recall of what happened to me - and a tendency to hallucinate. Some of those experimented on never recovered. But the Operation continued, using different drugs in different doses, rather as if they were mixing shades of paint and they might strike it lucky and get Intelligence gold.’

‘The US Navy gave up in 1953 – and then the CIA took over. By that time, however, the drugs were being used as accompaniment to traditional interrogation techniques not as a substitute.

‘A year on I was given a medical. My blood pressure was still high and I was told my heart had probably been permanently affected and I shouldn’t expect a long life. The problem I experienced longest was what I called the see-saw. I’d suddenly get the impression the floor was tilting and I’d slide off. I’d move – but if I moved too far, the floor would start tilting the other way. That lasted until about 1950 and I got into the habit of adjusting my stance. Someone once asked me if I had been a long time at sea.’

‘Didn’t the British say anything else?’

‘No. Not really. Quite soon I realized it was being treated as a sort of joke. The Americans had pumped drugs into me and I had really suffered very few after-effects.

‘Oh,’ he added. ‘I did get to see a very slim report later in my career. The experience was described as a ‘crash course in realism and the benefits of self-reliance. The subject came through the trial well.’

We talked some more.

‘Intelligence services everywhere believe and want others to believe that they deal in much harsher realities than the people they are supposed to defend can bear. That’s what justifies their existence, usually in the claim that they must have the knowledge and capabilities to ward off an enemy as cruel and now as fanatical as can be imagined. I suppose there’s a valid point in there somewhere.’

‘Did you feel betrayed?’

He smiled. ‘It’s not that sort of business. I certainly didn’t imagine any other Intelligence service would behave better. People want to believe what they want to believe. They’ll change the facts. They’ll develop myths. But even there, all myths are a compromise between what you want to think and what is acceptable and attractive to others round you.’

Black Bear is of course fiction – but I thought truth drugs and the myths around them made for a particularly gruesome kind of violence: silent, bloodless, but truly hard to combat.

Published on April 27, 2013 14:04

Myth Making as Compromise - The ‘Real’ Peter Cotton, Part 5

It’s been some time since I wrote about the ‘real’ Peter Cotton. There is more to add. I am now able, for example, to say what his real name was – David Collingwood (1919-2011). And since he had a considerable amount to do with the subject of Black Bear, now about to be published, it is time I made his contribution clear.

As I have mentioned in previous blog posts (collected together here on my website) I met him in 2005 when he had a house in Guadalajara in Spain. He was a widower, his second wife, Helen, had died the year before and the introduction was made by his step-daughter Caroline. I have also mentioned that I made about nine hours of recordings of what he had to say over several meetings.

What I haven’t mentioned is that he showed me various documents, ‘scraps’ he called them, ‘of the myths we are all subject to.’

One of these was an extraordinary document written by a G F Bakewell in 1947 ‘in light of the current interest in Human Rights.’ The ‘current interest’ was of course the United Nations Charter and the preparation of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). The ‘paper’ was quite long and was an entirely straight-faced attempt to suggest that the use of ‘so-called truth drugs could be construed as being in the spirit of Human Rights Legislation.’

The gist of G F Bakewell’s argument was that such drugs ‘could assist Intelligence Agencies obtain information from unwilling subjects without recourse to torture.’

David Collingwood laughed. It sounded perfectly genuine. I have said before he was rather old-fashioned and amiably patrician in manner but also something of a dramatic story-teller.

‘You see physical violence is so visible. Blood, the fragility of human bodies, distraught witnesses – the horror is obvious.’

I had just been doing voice-over work on a documentary about the Madrid bombings; indeed his step-daughter Caroline runs the studio where the voice-over was done.‘Now imagine what it’s like to be punched in the brain. It’s a perfect match of physiological and psychological attack, certainly if you are unsuspecting.’

In an earlier blog I mentioned Mr Collingwood’s interest in the late Sir Peter Russell, called Peter Wheeler (his birth name) in some Javier Marias novels. Following a bad accident in WW2, Sir Peter was taken away and beaten up by his own side – ostensibly to help him should he face torture at the hands of the Nazis.

The point? British intelligence was not averse to treating its own quite as badly as any enemy would.

While writing Black Bear this aspect of historical reality led to some problems. My editor and publishers disliked the notion that Cotton’s superiors would have connived in what happened to him.

David Collingwood was in no doubt when considering his own case.

‘Christ, yes,’ he said. ‘They gave permission without my knowledge or much thought on their part.’

In 1947 the US Navy or Senior Service began Operation Chatter. They had dibs as it were on the new thinking as described by G F Bakewell. As a result, several thousand people, quite a few volunteers, were subjected to various drugs without understanding what they might experience or what risks they were taking.

David Collingwood said he received multiple doses of scopolamine, mescaline and sodium amytal. ‘Or at least that was what I was later told.’

‘Scopolamine is the “Devil’s Breath”, supposedly much used by criminals in Columbia. It comes from a rather pretty plant. Mescaline is peyote of course. Sodium Amytal was developed by the Germans. It really gets your heart rate up.’

The purpose? ‘Basically to see what happened when you pumped these things into a male of 28 in reasonably good health. It was a kind of jab and see. I assure you the British I saw after the experience were mostly interested a) in whether or not the drugs had rendered me impotent and b) whether I had suffered any hair loss. That was exactly the same as worries about radiation sickness.

‘The so-called experiments were to see whether there might be a magic key to unlocking someone’s mind. I never saw my results, though I was told I had been a useless subject. In any case, the obvious effects of each drug were pretty much established as far as intelligence was concerned. You got drunk-style rambling, acute memory loss – I still have no recall of what happened to me - and a tendency to hallucinate. Some of those experimented on never recovered. But the Operation continued, using different drugs in different doses, rather as if they were mixing shades of paint and they might strike it lucky and get Intelligence gold.

‘The US Navy gave up in 1953 – and then the CIA took over. By that time, however, the drugs were being used as accompaniment to traditional interrogation techniques not as a substitute.

‘A year on I was given a medical. My blood pressure was still high and I was told my heart had probably been permanently affected and I shouldn’t expect a long life. The problem I experienced longest was what I called the see-saw. I’d suddenly get the impression the floor was tilting and I’d slide off. I’d move – but if I moved too far, the floor would start tilting the other way. That lasted until about 1950 and I got into the habit of adjusting my stance. Someone once asked me if I had been a long time at sea.’

‘Didn’t the British say anything else?’

‘No. Not really. Quite soon I realized it was being treated as a sort of joke. The Americans had pumped drugs into me and I had really suffered very few after-effects.

‘Oh,’ he added. ‘I did get to see a very slim report later in my career. The experience was described as a ‘crash course in realism and the benefits of self-reliance. The subject came through the trial well.’

We talked some more.

‘Intelligence services everywhere believe and want others to believe that they deal in much harsher realities than the people they are supposed to defend can bear. That’s what justifies their existence, usually in the claim that they must have the knowledge and capabilities to ward off an enemy as cruel and now as fanatical as can be imagined. I suppose there’s a valid point in there somewhere.’

‘Did you feel betrayed?’

He smiled. ‘It’s not that sort of business. I certainly didn’t imagine any other Intelligence service would behave better. People want to believe what they want to believe. They’ll change the facts. They’ll develop myths. But even there, all myths are a compromise between what you want to think and what is acceptable and attractive to others round you.’

Published on April 27, 2013 09:41

April 22, 2013

Thriller Taxonomy

In two years’ time it will be a century since John Buchan published The Thirty-Nine Steps.

The dedication to Buchan’s friend Tommy Nelson is also famous. In it, the creator of Richard Hannay mentions their mutual ‘affection for that elementary type of tale which Americans call the “dime novel” and which we know as the “shocker” – the romance where the incidents defy the probabilities, and march just inside the borders of the possible’. John Buchan calls these productions ‘aids to cheerfulness’.

In the time since Buchan’s 39 Steps was first published, this short novel has been called a ‘thriller’, an ‘action novel’, a ‘spy story’ or variations on these. These descriptions are not quite the same thing but the book certainly set the standard for a type of adventure story. I am going to use the expression ‘a fast-moving combination of brain and brawn’.

Buchan brilliantly exploited the image of a respectable man running for his life in a world that appears, at least superficially, settled and civilized.

Of course, since then, thrillers, action novels and spy stories, have moved on. Think how Richard Hannay would get on nowadays. People sometimes do.

In the history of this most capacious genre however other writers brought in developments. Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male (1939), for example, shows a hunter trying to shoot a Hitler-like character in revenge for the death of a love who happens, not at all incidentally, to be Jewish. This is at least more WW2 than WW1, less gung-ho, a deal more brutal.

This is not to demean Buchan. In August 1914, my husband’s great-grandfather and grandfather (then 63 and 38 respectively) took a train south from the North of Scotland to join up, and were seriously annoyed not to be accepted, one on the grounds of age, the other because of what was then called ‘a gammy leg’.

I suppose the next real shift was John Le Carré who caught the Cold War greyness, paranoia, muddle and just a touch of romantic morality in The Spy Who Came in from The Cold (1963).

It’s the fiftieth anniversary of the book in September this year. What has happened half a century on?

In my own case, four books into the Peter Cotton series (Black Bear comes out next month), I am getting to the stage of understanding a bit more of what I have been trying to do in the genre. I have also understood that the whole genre or classification aspect of publishing is too often misleading the reader. If asked for a quick description of my books I’d say ‘Intelligence stories’.

I say this because Amazon has pre-publication reviews and one of the reviewers of Black Bear says he can see the ‘brain’ but misses the ‘brawn.’ Quite right too. I have to admit I wanted to write a bloodless book. Rather more positively I wanted to concentrate on the insidious violence of so-called ‘truth-drugs’. No, I don’t think I am writing about an objective ‘reality’ but about historical circumstances and stresses in the late 1940s, when what became the Cold War and a stand-off was something of a jostle, full of authoritarian incompetence, misunderstandings and – there’s a certain consistency here – the disposability of people who, wittingly or not, get involved.

Now I can appreciate that physical violence – torture, for example – can cause a degree of turmoil in the reader, but there are other kinds of non-splat violence. My question really is – how do you use your brain when your brain has been affected or attacked by chemical means? At one level you have to know who you are fighting and the arms you have at your disposal.

Published on April 22, 2013 05:43

April 4, 2013

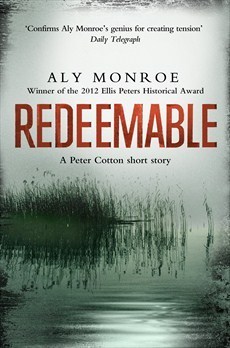

Redeemable - now available

Redeemable, an original Peter Cotton short story set in Germany, between The Maze of Cadiz and Washington Shadow, is now available for download - click here - price £1.99.

A month to go before the publication of Black Bear, Peter Cotton #4 available for pre-order - click here

Published on April 04, 2013 10:09

March 4, 2013

Redeemable - one month to go

Just one month to go before the publication of the new Peter Cotton short story, Redeemable (pub day 4 April 2013) You can pre-order it from Amazon now - a little something before Black Bear comes out on 9 May

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Redeemable-Eb...

Published on March 04, 2013 09:27

February 17, 2013

Panels at CrimeFest

The panels are gradually being formed for CrimeFest 2013 held in Bristol 30 May – 2 June. I’m delighted to be on two panels, both on Saturday 1 June, with a really interesting group of authors:

10:10 - 11:00 -' Cold War: An Infiltrating Chill'. On the panel will be Tom Harper, John Lawton, Aly Monroe and William Ryan, and our moderator will be Martin Walker.

15:20 - 16:10 p.m. – ‘Honour Among Spies?’ with Charles Cumming, Jeremy Duns, Aly Monroe and Chris Morgan Jones. Michael Ridpath will be our participating moderator.If you’re in Bristol then, we'd love to see you there. It should be fun.

Published on February 17, 2013 04:51

January 30, 2013

What's in a Name?

For reasons I can’t fully explain I like some of my characters to share a name with someone outside the books.I have to say readers don’t usually notice. Indeed until now nobody has remarked on it.On Rob Kitchin’s blog The View from the BlueHouse, however, following his review of Icelight, a comment by a Dr Evangelicus shows someone has seen that the Special Branch Sergeant Dickie Dawkins was christened Richard. Richard Dawkins, as readers of this will know, is also the name of a scientist famous for books like The Selfish Gene, and his public stance as an atheist.

Again in Icelight, Cotton has a neighbor called Michel Shaloub, which is the real name of the actor Omar Sharif.

I wish I could say how and why I chose those particular names. And I have no idea why I thought that not Jon Stewart (The Daily Show) but his mother should have a character named after her in Black Bear.

Published on January 30, 2013 03:21

January 26, 2013

Redeemable - cover

Here is the cover of my Peter Cotton e-story that will be available on 4th April - one month before the publication of Black Bear. The story is set in Germany, July 1945. From poverty-stricken Madrid, Peter Cotton is sent to the British Zone of Occupation, first to Hamburg, then to Lüneberg, headquarters of the Second Army. The troops have been told to be 'conquerors, not oppressors'. They have discovered that in Germany, they are rich and can get richer. The black market is blatant and comes in many shades and temptations ...

Published on January 26, 2013 08:56