Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 68

October 21, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – The life and death Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France

In February 1781, Marie Antoinette realised she might be pregnant again.

In the middle of March, she wrote to Madame de Mackau, “I am going to cause further bother because I am enceinte. I assure you that in spite of my joy, I regret the increase in your trouble.”1 She had given birth to Marie-Thérèse, Madame Royale, in 1778, but she could not inherit the French throne. By May, the pregnancy was public knowledge.

On the morning of 22 October 1781, Marie Antoinette went into labour. The people allowed into the room were limited as the Queen had fainted during her first labour. Her husband later wrote in his diary, “At exactly a quarter past one by my watch, she was successfully delivered of a boy.”2 Marie Antoinette was unaware of the sex of the child and initially assumed that it was another girl because everyone was quiet. King Louis eventually told her, “Madame, you have fulfilled our wishes and those of France, you are the mother of a Dauphin.”3 Holding the child, he told her, “Monsieur le Dauphin asks to come in.”4

The little boy was named Louis Joseph Xavier François, and he was baptised that same afternoon. His immediate care was in the hands of the Governess of the Children of France, the Princess of Guéméné. A Madame “Poitrine” was his wetnurse as there was no question of Marie Antoinette nursing him herself. The Princess of Guéméné resigned a year later due to enormous debt, and she was replaced by the Queen’s favourite, the Duchess of Polignac.

By the age of three, it was clear that the Dauphin had several health problems. After a bout of a severe illness at the age of two, his health remained a constant worry. One of his shoulders grew higher than the other, and he was frail and unable to play games with his sister. As his health deteriorated, Marie Antoinette gave birth to a second son – Louis Charles and a daughter, Sophie, who lived for just 11 months. Louis Joseph developed a hunched back, and he often had trouble breathing. He was moved to Meudon, where the air was better. However, by 1788, it was generally accepted that the boy would probably not live for very long.

Marie Antoinette wrote in February 1788, “My elder son has given me a great deal of anxiety. His body is twisted with one shoulder higher than the other and a back, whose vertebrae are slightly out of line and protruding. For some time, he has had constant fevers and, as a result, is very thin and weak.”5 She was describing tuberculosis of the spine. As tensions rose in the run-up to the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette and King Louis were in their own kind of hell with their son. In May 1789, Marie Antoinette wrote, “You will not find me very cheerful; I have a great deal on my heart.”6 By then, he could no longer walk, and he was emaciated. A wheelchair had been fashioned in green velvet with white wool cushions.

Marie Antoinette was visiting her son at Meudon when the end came on 4 June. King Louis had visited him the previous day, but he had returned home. The Dauphin died at one in the morning. When a delegation of the Assembly, demanded an audience that same day, King Louis cried, “Are there no fathers in the Assembly of the Third Estate?”7

Louis Joseph lay in state at Meudon, and his heart was removed to be taken to the Benedictine convent of Val-de-Grâce. He was given a simple funeral, considering the circumstances, as the proper rites would have cost up to 350,000 livres. The coffin was covered with a silver cloth, a crowd, a sword and the Orders of the Dauphin of France on top. He was buried in the Basilica of St. Denis.

Marie Antoinette later wrote, “At the death of my poor little Dauphin, the nation hardly seemed to notice.”8 The title of Dauphin now passed to Louis Charles.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – The life and death Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Book News Week 43

Book news week 43: 23 October – 29 October 2023

The Times British Royal Fashion

Kindle Edition – 26 October 2023 (US & UK)

Hunting the Falcon: Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, and the Marriage That Shook Europe

Hardcover – 24 October 2023 (US)

The post Book News Week 43 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 19, 2023

Royal Jewels – The Duchess of Teck’s Collet Necklace

The Duchess of Teck’s Collet Necklace, or at least part of it, was gifted to Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck, by her aunt, Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester. In 1856, Princess Mary Adelaide recorded the gift of “the promised necklace from dear kind aunt Mary.”1

When the Duchess of Gloucester died the following year, she received another gift of a “single row of diamonds” and other jewellery.2 The necklace was later inherited by the Duchess of Teck’s daughter, Queen Mary, who had another eight collet diamond necklaces, excluding the coronation necklace. She sometimes wore several at once, sometimes as many as seven.

The necklace was bequeathed to Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother and was later inherited by Queen Elizabeth II.

The post Royal Jewels – The Duchess of Teck’s Collet Necklace appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 17, 2023

Tlapalizquixochtzin – Queen regnant and the second Empress to Emperor Moctezuma II of the Aztec Empire

Tlapalizquixochtzin was the Queen regnant of the Aztec city-state, Ecatepec. She was also one of the two Empresses of Emperor Moctezuma II of the Aztec Empire. However, there is very minimal information regarding this little-known Queen regnant. Yet, it was clear that she ruled over a wealthy city-state and was the second most powerful woman in the Aztec Empire. Thus, her position was very unique to the Aztec Empire.

Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin’s life is mostly unknown. She was the daughter of King Matlaccoatzin of Ecatepec.[1] Her mother remains unknown. She had a brother named Chimalpilli and a younger sister named Tlacuilolxotzin.[2] After the death of King Matlaccoatzin, Prince Chimalpilli became the next King of Ecatepec.[3] After King Chimalpilli’s death, there were no male heirs.[4] Instead, the only suitable candidates were King Chimalpili’s sisters, Princess Tlapalizquixochtzin and Princess Tlacuilolxotzin.[5] Because Princess Tlapalizquixochtzin was the elder sister, it was decided that she should be the Queen regnant of Ecatepec.[6] Thus, Tlapalizquixochtzin became Queen.

There is very little information on the events during the reign of Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin. Ecatepec was a city-state that was located northeast of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.[7] It was a trading outpost for merchants who travelled north throughout the Aztec Empire.[8] Ecatepec was known for its abundance of salt and gold, which was very precious to the Aztec Empire.[9] Therefore, the city-state was very rich. Because of her wealthy city-state, Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin would have attracted many suitors.[10] Yet, her most illustrious suitor was Moctezuma II (the Aztec Emperor who would meet the famous Spanish conquistador, Hernan Cortez).

Emperor Moctezuma II saw the value of having Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin as his wife. Emperor Moctezuma II proposed to Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin, and she accepted.[11] Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin became the Empress of the Aztec Empire alongside his other Empress, Teotlalco.[12] Emperor Moctezuma II became King consort of Ecatepec.[13] He did not rule over Ecatepec but left the city-state solely in the hands of his wife.[14] Because Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin focused more on her rule of Ecatepec, she was not as close to Emperor Moctezuma II as Empress Teotlalco.[15] She bore a daughter named Doña Francisca de Moctezuma.[16]

Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin’s sister named Princess Tlacuilolxotzin married an Aztec nobleman from Tenochtitlan named Tecocomoctli Aculnahuacatzintli.[17] They had two sons. Their first son was Don Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin. Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin became the next King of Ecatepec and after Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin’s death.[18] After the Spanish conquered the Aztec Empire, King Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin became a governor in Mexico.[19] He later married Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin’s daughter, Doña Francisca de Moctezuma. Princess Tlacuilolxotzin’s second son was Don Francisco Matlaccoatzin, who went to Spain.[20] On 1 July 1520, Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin perished during Hernan Cortes’s retreat on Tenochtitlan known as The Night of Sorrows.

Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin was one of the two principal wives of Emperor Moctezuma II. Because she was mostly focused on ruling her city-state, she did not perform her duties as the Empress of the Aztec Empire like Empress Teotlaco. Queen Tlapalizquixochtzin played a very unique role in the Aztec Empire as a Queen regnant to a wealthy city-state and as the Empress. Even though there is very little information on her, it was clear that she was well-respected and admired by her people. She was able to hold on to her throne until her death, and her nephew succeeded her successfully. Hopefully, with more scholarship, further details on this little-known but fascinating Queen may be brought to light.

Sources:

Cabanillas, N. (n.d.). The Court of God-King Moctezuma II (PDF). GatorMUN XVII. Retrieved on January 2, 2023 from http://www.gatormun.org/uploads/5/1/3....

Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, D. F. D. S. A. M., Chimalpahin, D. D., & Ruwet, W. (1997). Codex Chimalpahin: Society and politics in Mexico Tenochtitlan, Tlateloloco, Texcoco, Culhuacan, and other Nahua Altepetl in Central Mexico : the Nahuatl and Spanish annals and accounts. (A. J. O. Anderson, Ed. & Trans.; S. Schroeder, Ed. & Trans.). United Kingdom: University of Oklahoma Press.

[1] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[2] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[3] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[4] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[5] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[6] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[7] Cabanillas, n.d.

[8] Cabanillas, n.d.

[9] Cabanillas, n.d.

[10] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[11] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[12] Cabanillas, n.d.

[13] Cabanillas, n.d.

[14] Cabanillas, n.d.

[15] Cabanillas, n.d.

[16] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[17] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[18] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[19] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

[20] Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, et al., 1997

The post Tlapalizquixochtzin – Queen regnant and the second Empress to Emperor Moctezuma II of the Aztec Empire appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 16, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – Reactions to Marie Antoinette’s execution

As the news of Marie Antoinette’s execution spread across Europe, reactions poured in.

Her niece Archduchess Marianne, the daughter of Emperor Leopold II, who had been born the day Marie Antoinette left for France, wrote to the Bishop of Nancy, “Monseigneur, I heard of the unfortunate Queen’s death in some black-sealed letters I received from Dresden. It is a terrible event.”1

Marie Antoinette’s sister Maria Carolina, Queen of Naples, was devastated. Maria Carolina – heavily pregnant with her 17th child – was so distraught that it was feared that she would lose the baby. She cried, “Good God! Did you ever think the French would have treated my sister and her husband in so horrible a way?”2 She gave birth to a healthy daughter two months later, but she did not rally quickly. She wrote, “I am so excessively ill that I can barely hold my pen and spend only the briefest time out of bed. The torments I have endured have ruined my health.”3

Her daughter, Princess Maria Amalia, later Queen of the French, wrote that her mother, with a face “bathed in tears”, took all of her children into the royal chapel for a special Mass to pray for Marie Antoinette, leaving them “awestruck as they saw their mother kneeling with a bowed head before the altar making intercessions for her sister’s soul.”4

When Naples finally made peace with France in 1796, Maria Carolina bitterly commented, “I am not and never shall be on good terms with the French… I shall always regard them as the murderers of my sister and the royal family.”5 She had placed a picture of her sister in her boudoir with the words, “I will pursue my vengeance to the grave.”6

Her sister-in-law, Marie Clotilde, the future Queen of Sardinia, was already devastated by the death of her brother, and the execution of Marie Antoinette only seemed to confirm the fears she had for her sister, Elisabeth, who was still imprisoned. Those fears were realised the following year.

Marie Antoinette’s sister Maria Christina was in shock. She wrote, “Maria Theresa would never have believed that she put children into the world who would be tortured by the vicious, oppressed by cabals, covered in ignominy and end their lives on the scaffold. I cannot get over the sorrow which the unfortunate had to suffer even in her last months, especially because of her children… death ends all grief and anguish.”7

Wilhelmina of Prussia, Princess of Orange, wrote to her daughter Louise, “You will learn by this post that the unfortunate Queen of France has just perished in the same manner as her spouse but in even more degrading and horrible circumstances. You will find some of the details in the Journal de la Guerre, and the Gazette de Leyde has a few more details. You will no doubt be as revolted as I am.”8

Marie Antoinette’s supposed lover, Count Axel von Fersen, wrote, “I could only think of my loss. It was dreadful to have no positive details. That she was alone in her last moments, without comfort, with no one to talk to, to give her last wishes to, is horrifying. The monsters from hell! No, without revenge, my heart will never be satisfied.”9 When he met her daughter several years later, he wrote, “My knees almost gave way beneath me as I was going downstairs after seeing her. I was profoundly moved by mingled feelings of joy and of sorrow.”10

Her nephew, Emperor Francis II, in Vienna, declared that the court should go into mourning, but her name was soon no longer spoken. Napoleon Bonaparte later said, “It was a fixed maxim in the House of Austria to maintain a profound silence concerning the Queen of France. At the name of Marie Antoinette, they lowered their eyes and changed the conversation, wishing to evade a disagreeable and embarrassing topic. Such was the rule adopted by the entire family and recommended to Austrian envoys in foreign parts.”11

Her sister-in-law, the Countess of Artois, had fled to Turin, and the Count de Maurienne simply wrote, “We have gone into mourning for the Queen.”12

Marie Antoinette’s daughter, Marie Thérèse had, remained imprisoned following the deaths of her father, mother, aunt and brother. She did not know that any of them had died until August 1795 when Madame de Chanterenne, her caretaker, finally told her. She had broken down in anguish, but after her release, she found it in her heart to write to her uncle, asking him to forgive the French people. She wrote, “Yes, uncle, it is she whose father, mother and aunt have been made to perish by them, who, on her knees, begs you for their grace and for peace!”13Many years later, she cherished the bloodstained shirt of her father, a lace bonnet worked on by her mother in Conciergerie and fichu that her aunt her worn to her execution, She often spent the days of her parents’ deaths alone in prayer.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – Reactions to Marie Antoinette’s execution appeared first on History of Royal Women.

New series about Queen Máxima to premiere in the spring of 2024

A new Dutch series called “Máxima” will premiere in the spring of 2024.

Its producer, Videoland, has shared the first images of the show, where Máxima Zorreguieta meets the then Prince of Orange. Although there is some foreign interest in the show, no international release date is known.

The post New series about Queen Máxima to premiere in the spring of 2024 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 15, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – The execution of Marie Antoinette

Just after midnight on 16 October 1793, her defence council was finally allowed to do its job.

Her two defence councillors, Chauveau-Lagarde and Tronçon-Ducoudray, quickly discussed their strategy, and it was decided that Chauveau-Lagarde would focus on her alleged conspiracy with the foreign powers while Tronçon-Ducoudray would focus on alleged conspiracy with enemies within France. They defended the Queen for three hours and called the evidence “ridiculously absent.”1 Marie Antoinette thanked Chauveau-Lagarde, and told him, “How tired you must be, Monsieur Chauveau-Lagarde! I am sensitive to all your troubles!”2 At three in the morning, Marie Antoinette was removed from the hall.

As the president instructed the jurors, he told them that Marie Antoinette was the “instigatrice of all the great tyrant’s crimes.”3 He added, “You have to judge the entire political life of the accused ever since she came to sit by the side of the last king of the French; but you must, above all, fix your deliberation upon the manoeuvres that she never for an instant ceased to employ to destroy the rising liberty.”4

An hour later, the jurors returned with a verdict, and Marie Antoinette was returned to the hall. The president read out, “The Tribunal, after the unanimous declaration of the jury, in conformity to the laws cited, condemns the said Marie Antoinette of Lorraine and Austria, widow of Louis Capet, to the penalty of death, her goods confiscated for the benefit of the republic, and this sentence shall be executed at the place de la Révolution.”5

Marie Antoinette showed no emotion. Chauveau-Lagarde later wrote, “The queen, sitting alone, listened calmly, and we could only realise that something had just taken place in her soul, something of a revolution that was very remarkable.” He added, “She did not give any sign of fear or indignation, or weakness. It appeared she was annihilated by surprise.6 Chauveau-Lagarde and Tronçon-Ducoudray were immediately arrested, but they were released later that same day.

Marie Antoinette walked up to the barrier behind which the crowd was watching and rose “her head majestically.”7 She was returned to her cell, where she sat down to write a final letter to Madame Elisabeth, her sister-in-law. She kissed the pages of the letter and gave it to the warden. Elisabeth would never receive the letter.

After praying, Marie Antoinette tried to sleep for a little while. Around 7 in the morning, her maid Rosalie found her on the bed, dressed in all black. Rosalie offered her something to eat, but Marie Antoinette replied, “My child, I no longer need anything; everything is over for me.”8 Shortly after, Rosalie helped her undress, but the guard who was situated in the room refused to give her privacy. She changed her chemise, which was covered in blood due to vaginal haemorrhaging. She put on a white negligee and draped a muslin scared over her shoulders. On her head, she wore a white mourning cap.

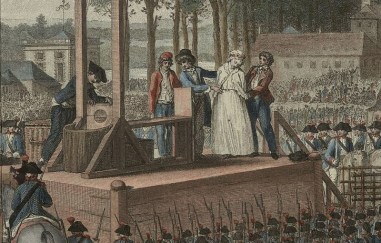

(public domain)

(public domain)A priest arrived, but she refused him, saying, “I thank you, but my religion forbids me to accept the forgiveness of God through a priest who is of another persuasion.”9 Around 10 in the morning, four officials arrived to read out the sentence, although Marie Antoinette protested that it was not necessary. She was then ordered to hold out her hands, which terrified her, and she said, “Will my hands be tied? The King’s hands were not tied.”10 Nevertheless, they were tied behind her back. Her hair was then cut, and a linen cap was placed on her remaining hair.

An open cart waited to take Marie Antoinette to the place of her execution. She was escorted from her cell, and she was helped into the cart. The priest, whom she had refused, sat next to her, and he told her to have courage. She countered with, “Courage? I have so long served an apprenticeship in it that is not likely to fail me today.”11 Crowds had gathered on the streets as the cart made its way. It stopped briefly in front of the women who had once marched on Versailles. One banner read, “Here’s the vile tyrant whom we hunted right in front of us!”12

(public domain)

(public domain)Just after noon, Marie Antoinette reached the guillotine, and the crowds fell silent. As she climbed the steps, someone shouted, “The infamous Autrichienne, she’s screwed!”13 She accidentally stepped on the executioner’s foot and quickly apologised, “Sir, I beg your pardon; I did not do it on purpose.”14 As the final preparations were made, Marie Antoinette prayed. She was then tied to the plank, and her head was held in place by the wood. With a pull of the cord, the blade fell – ending the life of an Archduchess, a Dauphine and a Queen. She was 37 years old.

The executioner showed her head to all four corners of the scaffold. Her head and body were taken to the Madeleine cemetery, where her husband had also been taken. The gravediggers had just started their lunch, and her body and head were left unattended on the grass. Two weeks after her burial, the bill came – six livres for the coffin and 15 livres and 35 sous for the grave and the gravediggers.15

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – The execution of Marie Antoinette appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 14, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – Day two of Marie Antoinette’s trial

On 15 October 1783, Marie Antoinette was taken to the Tribunal Hall shortly before 8 a.m. She wore the same dress as the day before.

Once again, witnesses were called, but this time, Marie Antoinette was given a more comfortable chair. She tapped her fingers on the arm of the chair, which gave an “appearance of unconcern.”1 One of the witnesses called today was Antoine Simon, who was taking care of Marie Antoinette’s son in the Temple. He testified that the family had a vast network of informants as they were always kept well informed, even when they were imprisoned.

She once again held up well against the testimonies, and her maid Rosalie later wrote, “I heard some people talking about the sitting; they said, ‘Marie Antoinette will obtain her freedom – she has answered well – they will only banish her.'”2 During the recess of an hour, Rosalie brought Marie Antoinette some soup.

After the final witness, around midnight, Marie Antoinette said, “Yesterday, I did not know the witnesses. I knew not what they were to depose against me, and nobody has produced against me any positive evidence. I finish by observing that I was only the wife of Louis XVI, and it was my duty to conform myself to his will.”3

Very little evidence was actually produced against Marie Antoinette, but as the clock struck midnight, the trial continued.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – Day two of Marie Antoinette’s trial appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Book News Week 42

Week 42 – 16 October – 22 October

Rain Dodging: A Scholar’s Romp through Britain in Search of a Stuart Queen

Paperback – 17 October 2023 (US & UK)

The post Book News Week 42 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 13, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – The start of Marie Antoinette’s trial

Marie Antoinette, widow of Louis Capet, has, since her residence in France, been the scourge and the bloodsucker of France.1

On 2 August 1793, Marie Antoinette had been moved from the Temple to the Conciergerie. She was kept there until the start of the trial on 14 October 1793.

Marie Antoinette had accepted the services of Chauveau-Lagarde and Tronçon-Ducoudray for her defence council. Both received the summons only hours before the start of the trial, and they arrived at her cell at six a.m. on the morning of the 14th. They found her dressed with “extreme simplicity.”2 They were only able to spent a total of three short consultations with her as they went over the indictment. They found the amount of evidence overwhelming and tried to ask for a delay. Marie Antoinette, although initially unwilling to address the National Convention, wrote to them that “I owe it to my children to omit no way of entirely justifying myself of these charges. My defenders ask for a delay of three days. I trust that the Convention will accord this to them.”3 Her request was ignored.

At eight in the morning, Marie Antoinette was escorted from her cell and taken to the Tribunal Hall. She was not chained up and walked freely in her black robe and bonnet. The crowds murmured as she walked in. Her maid later reported that they had taken her without allowing her to eat and drink, perhaps to weaken her before the tribunal. She remained standing as the jurors came into the hall and sat to her right. The judges sat on a platform on her left. Her council sat close by at a different table.

The president of the tribunal opened the session with the words, “Citizens, you have come to assist in the judgement of a woman whom your eyes have seen upon the throne and that you see, at this moment, at the bench reserved for the greatest criminals. The Tribunal, always equitable, requests that you be calm and peaceful. The law prohibits any sign of your esteem or condemnation.”4 The jurors were then sworn in, which took an hour.

After the indictment was read against her, the witnesses were called. There would be a total of 41 testimonies, of which 13 were detrimental to her defence. The others were other neutral or favourable. Among other things, the witnesses spoke of “orgies”, which caused the downfall of France’s finances.5 They also alleged that Marie Antoinette molested her own son, to which she replied, “If I did not respond, it is because nature refuses to respond to such an allegation made against a mother.” She then appealed to the women in the room, “I appeal to the hearts of all mothers who are present in this room.”6

During recess, she was allowed to drink a little soup but she was weakened from a continual hemorrhage. Nevertheless, she had remained dignified throughout it all. It wasn’t until 11 in the evening that court was finally adjourned for the day. Chauveau-Lagarde later wrote, “That one could realise, if possible, all the fortitude the queen must have had to endure the fatigue of such long and horrible proceedings; on show before an audience; having to fight to defend herself against bloodthirsty monsters with traps set for her; and at the same time keep a demeanour worthy of herself.”7

As she returned to her cell, Marie Antoinette became faint. The lieutenant who helped her was arrested the following morning.

The trial would continue the following day.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – The start of Marie Antoinette’s trial appeared first on History of Royal Women.