Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 65

November 30, 2023

Royal Jewels – The Duchess of Gloucester’s Pendant Earrings

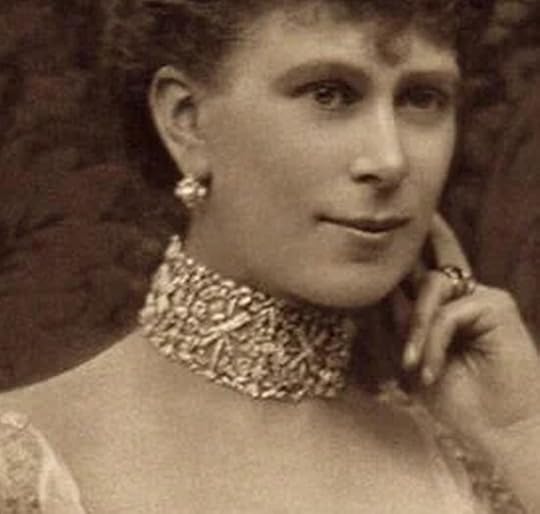

The Duchess of Gloucester’s Pendant Earrings were inherited by Princess Mary Adelaide, future Duchess of Teck, from her aunt, Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester, in 1857. They were then passed to her daughter, the future Queen Mary, upon her death in 1897.

The earrings each have a “detachable pendant pearl suspended from cut-down collets, within a scrolling, pavé-set frame.”1

Embed from Getty ImagesThe earrings were given to the future Queen Elizabeth II in 1947, and she wore the pearl tops on her wedding day in November 1947. The tops could easily be worn on their own, and Queen Mary sometimes wore them as pendants on a chain.

The future Queen Elizabeth II on her wedding day (public domain)

The future Queen Elizabeth II on her wedding day (public domain)Queen Elizabeth II has also worn the complete earrings.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post Royal Jewels – The Duchess of Gloucester’s Pendant Earrings appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 29, 2023

Review: Napoleon (2023)

From Ridley Scott comes the 2023 biopic Napoleon, starring Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon Bonaparte and Vanessa Kirby as Joséphine de Beauharnais. Napoleon rose to become Emperor of the French with Joséphine by his side, although he would later divorce her to marry the Austrian Archduchess Marie Louise to father an heir.

The film begins with the execution of Marie Antoinette which Napoleon watches from the crowd. This never happened, although I can understand adding a scene like this. Also in contradiction to what was shown, Marie Antoinette had her hands bound, was wearing white and had had her hair chopped off. We see how Joséphine was released from prison, although her husband had been executed and how she meets Napoleon by chance. They have an immediate connection and after an endearing scene in which her son requests Napoleon to return his executed father’s sword, a romance begins.

This romance is often interrupted by Napoleon’s military campaign. I will be the first to admit I know nothing about how factual those battle scenes are, although I’ve read that they leave something to desire. The scenes are often narrated by Napoleon’s passionate letters to Joséphine, although the real ones are certainly quite a bit more racy. The film completely glosses over the age difference between Joséphine and Napoleon, which is a shame.

As Napoleon rose to power, he doled out power and kingdoms to his brothers and sisters and arranged advantageous marriages. However, none of this is covered in the film. His younger brother Lucien makes a few brief appearances and his sisters are background players during his coronation scene. Hortense, his stepdaughter and later also his sister-in-law and mother of the future Emperor Napoleon III, gets a few lines to explain her mother’s death. His mother has a brief scene where she snubs Joséphine. It feels like a missed opportunity to highlight this interesting family and how their influence truly spread so far.

After his divorce from Joséphine, we are presented with a timidly smiling Marie Louise. It’s her one and only appearance, and although she is later credited with the birth of a son, she is never mentioned again. Again, this seems like a lost opportunity.

Overall, this film has plenty of things wrong with it, but it also gets a lot right. Vanessa Kirby is a wonderful Joséphine, and Joaquin Phoenix makes a brilliant Napoleon. I enjoyed the battle scenes, even knowing that they weren’t factual. The coronation scene was a feast for the eyes as well.

I think perhaps this subject would be better served with a series rather than a film. It would have allowed for more depth instead of just hopping from battle to battle.

Napoleon is in theatres now.

The post Review: Napoleon (2023) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 28, 2023

María Teresa Rafaela of Spain – The Dauphine who found a warm and pure heart

María Teresa Rafaela of Spain was born on 11 June 1726 as the daughter of King Philip V of Spain and Elisabeth Farnese. From her father’s first marriage, she had two surviving half-brothers. She also had five full siblings. María Teresa Rafaela was born Royal Alcazar of Madrid in Spain, and she was under the care of her governess, the Marchioness Las Nieves.

Her elder sister, Mariana Victoria, had been sent to France at the age of 4 as the future bride of the then ten-year-old King Louis XV of France. However, the engagement was broken off in 1725, and she was sent back to Spain in disgrace. This caused a diplomatic rift, which would eventually be settled with the marriage of María Teresa Rafaela to King Louis XV’s son in 1745. This marriage had been settled in 1739 but would have to wait for six years. María Teresa Rafaela’s mother had been adamant that no wedding should take place until both parties were of marriageable age.1

María Teresa Rafaela was married to the Dauphin, Louis, on 18 December 1744 by proxy, and she departed from her homeland in January 1745. Preparations for her arrival in France began in earnest; balls were scheduled, and fireworks were ordered. One lawyer wrote, “Madame la Dauphine is advancing; they say that she has a lot of spirit, that she knows several languages and that she has been given an education above her sex. She is nearly nineteen, therefore the age to think and speak. She is tall with dignity; it is said that the Duchess of Brancas, her lady-in-waiting, wanted to engage her to put on rouge, which was the custom in France, and that it suited her better than another. She replied that if the King and Queen, and Monsieur the Dauphin, ordered her to, that she would put some on.”2

María Teresa Rafaela arrived on 21 February at Etampes, where she fell on her knees upon meeting the King. He raised her up, kissed her and introduced her to her future husband, who kissed her on both cheeks. The in-person wedding took place two days later at Versailles. King Louis XV and the court were initially satisfied, but the Dauphin was even more so, and he fell head over heels in love. After the wedding ceremony in the morning, there was a play, a ballet, and a public supper before the bedding ceremony took place. During these festivities, King Louis met his soon-to-be mistress, Madame de Pompadour. María Teresa Rafaela did not approve of her and became openly hostile, leading to a frosty relationship with the King. Once, when Madame de Pompadour had accidentally fallen into a basin at Fontainebleau, María Teresa Rafaela reportedly mumbled that she was a “fish [poisson – which had been Madame de Pompadour’s surname] returning to her elements.” 3

In May, the King and the Dauphin left for Flanders to join the army, leaving María Teresa Rafaela in tears. She found solace with her mother-in-law, Queen Marie Leszczyńska. The Dauphin excitedly wrote home after the victory at the Battle of Fontenoy. They returned home to Versailles in September, and he fell into an easy routine with María Teresa Rafaela. They dined together often, and after dinner, he read to her.

María Teresa Rafaela soon fell pregnant with her first child, and the birth was eagerly awaited. Even the King did not venture too far away so he would be able to witness the event. She seemed to have fared well in her pregnancy, and she gave birth to a healthy baby girl on 19 July 1746. The court had not informed her that her father had died on 9 July to prevent her from going into shock. The waiting crowds learned from the sour face of her lady-in-waiting that there was not to be a Duke of Burgundy. The little girl was named Marie Thérèse, but she went by the honorific Madame.

Tragically, María Teresa Rafaela died just four days after giving birth, plunging her husband into despair. The King had to drag his son away from his wife’s deathbed. The Duke de Luynes wrote, “Madame la Dauphine made her confession, she was bled twice on her feet, a general suppression made her lose consciousness, and she died. The Dauphin loved his wife passionately, and the blow he felt was terrible. His pain first manifested itself violently; he cried a lot and isolated himself for a few days.[…] The Dauphine was also little regretted at court, reserved and haughty, she had failed to please.[…] She had found, however, what is not given to all women, a warm and pure heart, which had loved her undividedly. Her image was never erased from the mind of the Dauphin, who, in his will, asked that his heart be placed next to that of his first wife.”4

As Versailles went in mourning, María Teresa Rafaela was subjected to autopsy. The doctors reportedly found a great deal of milk in her brain.5 Her heart was also removed, as per custom.

She was later decided as the “little girl, so shy that some people thought her half-witted, had made no impression whatever on those around her.” 6 She was certainly replaced in a hurry, as Louis married Maria Josepha of Saxony early the following year. Louis continued to mourn her and was even more devasted when their little daughter died on 27 April 1748.

The post María Teresa Rafaela of Spain – The Dauphine who found a warm and pure heart appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 26, 2023

Cypros II – The Jewish Queen who made a tapestry of the ancient world

Queen Cypros II was the wife of King Herod Agrippa I of Judea. Queen Cypros II was once an artist who made a map of the ancient world on a tapestry.[1] Sadly, her tapestry has been lost to us in history.[2] Queen Cypros II also had two coins made in her image.[3] Thus, she was a respected and admirable queen.

Queen Cypros II was born in circa 10 C.E.[4] She was the daughter of Salampsio (the daughter of King Herod the Great and his executed wife, Queen Mariamne I and Phasael II (the nephew of King Herod the Great).[5] Therefore, Cypros II was descended from both the Herodian and the Hasmonean royal dynasties.[6] Cypros II was named after Cypros I, the mother of King Herod the Great.[7]

Sometime after 23 C.E., Herod Agrippa I arrived in Judea after living in Rome. He married his cousin, Cypros II.[8] According to Josephus, Herod Agrippa was often depressed because he lived in political obscurity within the Judean court and often contemplated suicide.[9] In 25 C.E., Cypros II, fearing that her husband would actually commit suicide, wrote to Herodias (her sister-in-law) for a job promotion.[10] With Herodias’s help, Herod Agrippa I was made the inspector of the markets of Tiberia.[11] However, historian Tal Ilan doubts Josephus’s story because it seemed like a network connection between women who manipulated their husbands in politics.[12] Cypros II gave birth to four children. They were Herod Agrippa II, Julia Berenice I, Mariamne, and Drusilla.

In 34 C.E., Herod Agrippa I was displeased with his post and resigned.[13] He decided to return to Rome.[14] Cypros II accompanied her husband to Alexandria while he was en route to Rome.[15] Once she arrived, she obtained a loan from Alexander, the chief magistrate of the Jewish community in Alexandria. This loan funded her husband’s living expenses in Rome.[16] In 36 C.E., Emperor Caligula made Herod Agrippa I the King of Judea.[17] Thus, Cypros II became Queen of Judea.

King Herod Agrippa II had two coins of his wife that bear the inscription, “Cypros”[18] or “Queen Cypros”[19] on them.[20] On one coin is Queen Cypros II’s bust.[21] On another coin Queen Cypros II “is standing, face forward.”[22] These coins are evidence that King Herod Agrippa II greatly respected his queen.[23] King Herod Agrippa II also erected statues of his daughters in his palace in Caesarea.[24] King Herod Agrippa II died in 44 C.E. Queen Cypros II outlived her husband.[25] She died circa 50 C.E.[26] She was said to be a great artist.[27] There is an epigram of her that is attributed to Phillip of Thessalonica.[28] It went:

“Modeling all with shuttle laboring on the loom, Cypros made a perfect copy of the harvest-bearing earth, all that the land-encircling ocean girdles, obedient to great Caesar, the grey sea too…it was a Queen’s duty to bring gifts so long due to gods.”[29]

In this epigram, Mrs Tal Ilan believes that it showed Queen Cypros II was a talented artist who made a tapestry of the ancient world that was greatly admired.[30] This may have proven that Queen Cypros II may have been knowledgeable in both geography and cartography.[31] While very few facts about Queen Cypros II are known, it is clear that she was a respected queen and an artist.[32] She was deeply admired by her husband and her contemporaries. It is truly sad that her tapestry has not survived today.[33]

Sources:

M. Brann (.1906). “Agrippa II. (M. Juliius Agrippa, also known as Herod Agrippa I.)”. The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved on April 28, 2023 from https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/ar....

Ilan, T. (2022). Queen Berenice: A Jewish Female Icon of the First Century CE. Netherlands: Brill.

[1] Ilan, 2022

[2] Ilan, 2022

[3] Ilan, 2022

[4] Ilan, 2022

[5] Ilan, 2022

[6] Ilan, 2022

[7] Ilan, 2022

[8] Ilan, 2022

[9] Ilan, 2022

[10] Ilan, 2022

[11] Brann, 1906, “Agrippa II. (M. Juliius Agrippa, also known as Herod Agrippa I.)”

[12] Ilan, 2022

[13] Brann, 1906, “Agrippa II. (M. Juliius Agrippa, also known as Herod Agrippa I.)”

[14] Brann, 1906, “Agrippa II. (M. Juliius Agrippa, also known as Herod Agrippa I.)”

[15] Ilan, 2022

[16] Ilan, 2022

[17] Brann, 1906, “Agrippa II. (M. Juliius Agrippa, also known as Herod Agrippa I.)”

[18] Ilan, 2022, p. 44

[19] Ilan, 2022, p. 44

[20] Ilan, 2022

[21] Ilan, 2022

[22] Ilan, 2022, p. 44

[23] Ilan, 2022

[24] Ilan, 2022

[25] Ilan, 2022

[26] Ilan, 2022

[27] Ilan, 2022

[28] Ilan, 2022

[29] Ilan, 2022, p. 45

[30] Ilan, 2022

[31] Ilan, 2022

[32] Ilan, 2022

[33] Ilan, 2022

The post Cypros II – The Jewish Queen who made a tapestry of the ancient world appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 25, 2023

Book News Week 48

Book news week 48: 27 November – 3 December 2023

Catherine the Great and the Culture of Celebrity in the Eighteenth Century (Cultures of Early Modern Europe)

Paperback – 30 November 2023 (US & UK)

Henry VIII’s True Daughter: Catherine Carey, A Tudor Life

Hardcover – 30 November 2023 (UK)

On The Trail of Mary Queen of Scots

Paperback – 30 November 2023 (UK)

Reconciliation and Resistance in Early Modern Spain: Hernando de Baeza and the Catholic Monarchs

Paperback – 30 November 2023 (US)

Palaces of Reason: The Royal Residences of Bourbon Naples

Hardcover – 28 November 2023 (US)

The post Book News Week 48 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 24, 2023

Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines – The heroic actions of the first Empress of Haiti

Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines was the first Empress of Haiti. She was the wife of Emperor Jean-Jacques Dessalines of Haiti. She was also the first recorded nurse in Haitian history.[1] Empress Marie-Claire Dessalines was known for her charitable acts.[2] During Haiti’s turbulent times, she managed to save countless lives. It is no wonder why her story continues to inspire many Haitians today.

In 1758, Empress Marie-Claire Dessalines was born in Léogâne. She was born into a free black family.[3] Her father was Guillaume Bonheur. Her mother was Marie-Elizabeth Saint Lobelot. She studied under her maternal aunt, Elise Lobelot, who was a governess and housekeeper under the religious order of Saint Domingue.[4] She eventually married Pierre Lunic, a French cartwright who worked for the religious order of Saint-Jean de Dieu in Port au Prince.[5] In 1795, Marie-Claire was widowed at the age of thirty-seven.[6]

During the siege of Jacmel in 1800, Marie Claire worked tirelessly for the wounded and the starving.[7] She managed to convince Jean-Jacques Dessalines, her longtime lover and a member of the besieging parties, to open some of the roads of Jacmel in order to receive aid.[8] She then gathered women and children and led a procession carrying medicine, food, and clothes back into the city.[9] Then, she arranged for food to be cooked on the streets.[10]

On 2 April 1800, Marie-Claire married Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Jean-Jacques Dessalines was described as a carefree man who loved dancing.[11] Marie-Claire was described to be “merciful, natural, elegant, and cordial.” [12] Marie-Claire’s first act in her marriage was to legitimise the children she had with Jean-Jacques Dessalines before their marriage.[13] They were Marie-Françoise, Celestine, Jeanne, Serine, Albert, Jacques, and Louis.[14] She also adopted Jean-Jacques Dessalines’s four illegitimate children.[15] The couple settled in Marchand, which was Haiti’s first black capital.[16] She shielded the children from violence by eliminating weapons in their home.[17]

Through the months of January to April of 1804, Marie Claire worked tirelessly to rescue prisoners and save many of them from battle wounds.[18] In the meantime, her husband killed five thousand white people in order to get the French and the Germans off the island.[19] On 1 January 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines ordered Marie-Claire to cook a freedom soup to honour the liberation of the former slaves.[20] In 1804, Haiti was made into a monarchy known as the First Empire of Haiti.[21] Jean-Jacques Dessalines became Emperor, and Marie-Claire was Empress.[22] On 8 October 1804, Emperor Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Empress Marie-Claire were crowned at the Church of Champ de Mars.[23] On 12 August 1805, Empress Marie-Claire acquired a feast day that coincided with St. Clare of Assisi.[24] Marie-Claire would be the Empress of Haiti for two years.

On 17 October 1806, Emperor Jean-Jacques was assassinated. Empress Marie-Claire was given the title of Princess Dowager. However, all her lands were confiscated, leaving her penniless.[25] Marie-Claire struggled to raise her five surviving children, who were between the ages of seven and seventeen, by herself.[26] During the mass murder of 1809, Princess Marie-Claire hid a botanist named Michel Etienne Descourtilz under her bed.[27] Princess Marie-Claire also saved the orphaned sisters, Hortense and Augustine Saint-Javier, who were the last white people living on the island.[28] Princess Marie-Claire provided passports for the girls.[29] On 20 August 1809, Princess Marie-Claire sent the girls on a ship from Cap Francais to New York, where their relatives awaited them.[30]

Princess Marie-Claire settled in Saint-Marc, a seaside town on Western Haiti.[31] She constantly struggled with poverty.[32] In 1849, Emperor Faustin I of Haiti increased Princess Marie-Claire’s pension as a sign of respect that she was once an empress.[33] However, Princess Marie-Claire refused Emperor Faustin I’s money.[34] Therefore, Princess Marie-Claire continued to live in poverty until her death.[35] On 8 August 1858, while living with her granddaughter, Princess Marie-Claire died at the Ville de l’Indepence in Gonaïves.

Empress Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines has been known for her acts of benevolence.[36] In honour of her legacy, Dr Bayyniah Bello established the Foundation Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines after the 2010 Haiti earthquake.[37] The foundation provided both educational and social support to the victims of the earthquake.[38] There are also many public schools that are named in her honour.[39] Because of her charitable acts, Empress Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines will continue to be a role model and cultural symbol for many people in Haiti.

Sources:

Hall, M. R., Vilsaint, F. (2021). Historical Dictionary of Haiti. NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Louis, F. (December 15, 2015 ). “1. Marie Claire Heureuse Bonheur, infirmière (1758-1858) [1. Marie Claire Happy Happiness, nurse (1758-1858)]”. scienceetbiencommun.pressbooks.pub. Retrieved on 6 February 2023 from https://scienceetbiencommun.pressbook....

Snodgrass, M. E. (2019). Caribbean Women and Their Art: An Encyclopedia. NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

[1] Louis, 15 December 2015 “1. Marie Claire Heureuse Bonheur, infirmière (1758-1858) [1. Marie Claire Happy Happiness, nurse (1758-1858)]”

[2] Snodgrass, 2019

[3] Snodgrass, 2019

[4] Snodgrass, 2019

[5] Snodgrass, 2019

[6] Snodgrass, 2019

[7] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[8] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021; Snodgrass, 2019

[9] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[10] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[11] Snodgrass, 2019

[12] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021, p. 53

[13] Snodgrass, 2019

[14] Snodgrass, 2019

[15] Snodgrass, 2019

[16] Snodgrass, 2019

[17] Snodgrass, 2019

[18] Snodgrass, 2019

[19] Snodgrass, 2019

[20] Snodgrass, 2019

[21] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[22] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[23] Snodgrass, 2019; Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[24] Snodgrass, 2019

[25] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021; Snodgrass, 2019

[26] Snodgrass, 2019

[27] Snodgrass, 2019

[28] Snodgrass, 2019

[29] Snodgrass, 2019

[30] Snodgrass, 2019

[31] Snodgrass, 2019

[32] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[33] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[34] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[35] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[36] Louis, 15 December 2015 “1. Marie Claire Heureuse Bonheur, infirmière (1758-1858) [1. Marie Claire Happy Happiness, nurse (1758-1858)]”

[37] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[38] Hall and Vilsaint, 2021

[39] Louis, 15 December 2015 “1. Marie Claire Heureuse Bonheur, infirmière (1758-1858) [1. Marie Claire Happy Happiness, nurse (1758-1858)]”

The post Marie-Claire Heureuse Félicité Bonheur Dessalines – The heroic actions of the first Empress of Haiti appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 23, 2023

Royal Jewels – Queen Mary’s Love Trophy Collar

Queen Mary’s Love Trophy Collar was made in March 1901 for the future Queen Mary when she was Duchess of Cornwall and York.

The collar is “formed of seven brilliant-set panels, each with an amatory trophy of bow, quiver and torch in a laurel-wreath oval suspended from a ribbon-tie, framed by foliate brilliant-set bands.”1

(public domain)

(public domain)The diamonds came from stars and diamond star earrings, which had been given by the Duchess of Cambridge, Queen Mary’s grandmother, in 1885 and from a floral spray given by her aunt Augusta, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, also in 1885.

The collar was given to the future Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, and it was inherited by Queen Elizabeth II in 2002.

The post Royal Jewels – Queen Mary’s Love Trophy Collar appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 21, 2023

Book Review: Traitor King: The Scandalous Exile of the Duke & Duchess of Windsor by Andrew Lownie

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor spent their entire life together in exile after the Duke had abdicated as King Edward VIII in order to marry the twice-divorced Wallis.

They were and still are strongly disliked, not in the least because of their apparent support of the Nazi regime. I won’t go into too much detail about my opinion of this, as I have already done so elsewhere.

Traitor King: The Scandalous Exile of the Duke & Duchess of Windsor dives deep into the evidence, although I am not sure if anything was actually “explosive” or “new.” A large part of the book focuses on the years around the abdication and the war years, which I understand as this is where the “scandalous” part of their exile takes place. The rest of their lives (and exile) isn’t covered quite as in-depth as the rest.

The book is quite interesting, but the disdain for the couple seems to drip from the pages. It’s fine to dislike them; even I don’t think very highly of them. Overall, I don’t think this book quite lives up to the claim on the cover.

Traitor King: The Scandalous Exile of the Duke & Duchess of Windsor by Andrew Lownie is available now in the US and the UK.

The post Book Review: Traitor King: The Scandalous Exile of the Duke & Duchess of Windsor by Andrew Lownie appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 19, 2023

La Malinche – The Princess who helped bring down the Aztec Empire

La Malinche has often been viewed as a traitor to her own people.[1] She was an indigenous princess who helped Hernan Cortes bring down the Aztec Empire. She has often been portrayed as deceitful and a trickster.[2] Yet, modern-day historians are very sympathetic to La Malinche.[3] She has been a victim of an institution that forced her into slavery.[4] While La Malinche’s reputation was very controversial, it is clear that she made a profound impact on Mexican history.

La Malinche’s original name was unknown.[5] Malinche was mostly a corrupted form of the Nahuatl name of Malintzin.[6] Her origins are still unclear.[7] Yet, it is generally agreed by historians who derived La Malinche’s early life from the Spanish conquistador named Bernard Diaz del Castillo, who knew her mother, that La Malinche was a princess of Painalla (a town on the southern borders of the Aztec Empire).[8] Her father was the Chief of Painalla.[9] Her father died when she was young.[10] Her mother married the next chief and had a son.[11] She viewed her daughter, La Malinche, as a threat to her son’s inheritance of Painalla.[12] Therefore, she decided to sell her into slavery.[13] La Malinche was at first sold to the Aztec tribe of Xicalango.[14] The Xicalango then sold her to the tribe of Tabasco.[15]

In 1519, the tribe of Tabasco gifted twenty slave women to Hernan Cortes.[16] One of these slaves was La Malinche.[17] They were baptised and converted to Catholicism. La Malinche was given the christened name Marina.[18] Hernan Cortes gave her to one of his captains named Alonso Hernández de Puertocarrera.[19] Thus, La Malinche seemed very insignificant to him.[20] Yet, La Malinche would soon prove to Hernan Cortes that she was a valuable asset.

La Malinche was described as being beautiful and intelligent.[21] She could speak seven Mayan dialects. Yet, she was most useful for speaking Nahuatl, which was the Aztec language.[22] After she was bought by the Spanish, she managed to learn Spanish within a few weeks.[23] Therefore, La Malinche would prove to be very useful to Hernan Cortes, whose main goal was to conquer the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.[24] Before Hernan Cortes discovered La Malinche’s talent, he used a Spanish priest named Gerónimo de Aguilar.[25] However, Gerónimo de Aguilar only knew the Mayan language and not Nahuatl.[26]

In July 1519, Hernan Cortes established a small garrison in Veracruz.[27] Yet, he could not communicate with the natives there because they spoke Nahuatl, and Gerónimo de Aguilar could not help him because he did not know the language.[28] However, La Malinche gained Hernan Cortes’s attention by proving that she could speak the Nahuatl language.[29] Therefore, Hernan Cortes began to rely on La Malinche for information and no longer needed Gerónimo de Aguilar.[30] Cortes sent La Malinche to ask the local chief at Veracruz to request a meeting between Moctezuma II (the Aztec Emperor) and Hernan Cortes.[31] However, Emperor Moctezuma II refused to meet with him.[32] Hernan Cortes initially did not want bloodshed because he was afraid he would lose many of his troops.[33] He used La Malinche to try to persuade the Aztecs to give him gold.[34] However, Emperor Moctezuma II’s refusal led Hernan Cortes with the choice to conquer the Aztec Empire.[35]

Hernan Cortes left Veracruz and eventually made his way north to Cempoala. Once he arrived, he learned the Chief of Cempoala was scared of the tax collectors from the Aztec capital.[36] Hernan Cortes used La Malinche to convince the chief to imprison the Tenochtitlan’s tax collectors.[37] The chief then befriended and became a Spanish ally.[38] However, Hernan Cortes secretly released two of the tax collectors sent from the capital as a request to befriend Emperor Moctezuma II.[39] When the Cempoalans learned what Hernan Cortes had done, they realised there was no way of escaping their alliance with the Spanish conquistadors because Emperor Moctezuma II may want vengeance.[40]

As the Spanish conquistadors continued to make their way to Tenochtitlan, they stopped at Cholula. However, the Cholulans made a secret plan to attack the Spanish conquistadors.[41] La Malinche learned of the plot by befriending the wife of the Chief of Cholula.[42] The chief’s wife begged La Malinche to switch sides.[43] She told her that after the Spanish conquistadors were massacred, La Malinche could marry her son.[44] La Malinche pretended to agree with the chief’s wife’s plan, but she relayed her plans to Hernan Cortes.[45] The Spanish conquistadors massacred the Cholulan nobles.[46] It was at this event that La Malinche first started to become a traitor who betrayed her own people.[47] After Cholula was destroyed, La Malinche appeared at Hernan Cortes’s side and marched off to Tenochtitlan.[48]

The meeting between La Malinche, Hernan Cortes, and Emperor Moctezuma II was one of the most pivotal events in Mexican history.[49] It also showed La Malinche’s importance during the Spanish conquest. During the meeting, La Malinche was looking and speaking directly to Emperor Moctezuma II.[50] When she and the Spanish conquistadors were installed in the palace, she summoned the servants to give them food.[51] She also summoned the Aztec nobles to give the Spanish supplies.[52] The Aztec nobles also talked to her and not to Hernan Cortes.[53] She was even given more gold than Hernan Cortes.[54] Therefore, La Malinche was not solely an interpreter. Instead, she was Hernan Cortes’s assistant and his mistress.[55] La Malinche was the most respected woman during the Spanish conquest.[56]

On 1 July 1520, La Malinche managed to survive and escape during the Night of Sorrows. When the Spanish learned that she had survived that tragic night, they were relieved and joyful.[57] In 1521, the Spanish conquistadors managed to destroy Tenochtitlan and capture Cuauhtémoc (the last Aztec Emperor). The fall of Tenochtitlan made La Malinche a very wealthy woman in the Spanish Empire.[58] La Malinche then settled in Coyoacán (which was located in present-day Mexico City). In 1523, La Malinche bore Hernan Cortes an illegitimate son named Martin.[59] Historians believe he was the first mestizo child born in the New World.[60]

In 1524, La Malinche accompanied Hernan Cortez on an expedition to Honduras to put down a rebellion.[61] En route, in Tiltepec, La Malinche married Captain Juan Jaramillo.[62] This marriage gave La Malinche her freedom and made her a member of the Spanish nobility.[63] Her dowry included the towns of Olutla and Xaltipan.[64] After La Malinche left Honduras, she gave birth to a daughter named Maria Jaramillo in 1526.[65] The couple settled in Orizaba, which was in Veracruz.[66] In 1528, Hernan Cortes left for Spain with Martin, his illegitimate son.[67] He did not take La Malinche with him.[68] Historians believed that she died that same year, most likely due to smallpox.[69]

La Malinche continues to be a divisive historical figure. Even though many viewed her to be a traitor, she was a pivotal figure during the events of the Spanish conquest. She was a very powerful and respected figure among both the Aztecs and the Spanish conquistadors.[70] She also became the mother of the Mexican identity.[71] La Malinche continues to be a popular icon. She has been the subject of movies, operas, plays, and novels.[72] Through the use of historical records and popular media, La Malinche’s reputation will continue to be scrutinised and examined for many years to come.

Sources:

Cypess, S. M. (1991). La Malinche in Mexican Literature from History to Myth. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Del Castillo, A. R. (2013). La Malinche. In P. L. Mason (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Race and Racism (2nd ed.). Gale. Credo Reference.

Hinojosa, R. D. M. (2013). The Ideological Appropriation of La Malinche in Mexican and Chicana Literature (PDF, master’s thesis). University of North Texas. Retrieved on 2 February 2023 from https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/....

“La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”. (2014). In J. Stock (Ed.), Global Events: Milestone Events Throughout History (Vol. 3). Gale.

McBride-Limaye, Ann (1988). “Metmorphoses of La Malinche and Mexican Cultural Identity,” Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 19 : No. 19, Article 2.

[1] Cypess, 1991

[2] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[3] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[4] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[5] Del Castillo, 2013

[6] Del Castillo, 2013

[7] McBride-Limaye, 1988

[8] McBride-Limaye, 1988

[9] Cypess, 1991

[10] Del Castillo, 2013

[11] Del Castillo, 2013

[12] Cypess, 1991

[13] Del Castillo, 2013

[14] McBride-Limaye, 1988

[15] McBride-Limaye, 1988

[16] Del Castillo, 2013

[17] Del Castillo, 2013

[18] Del Castillo, 2013

[19] Cypess, 1991

[20] Cypess, 1991

[21] Cypess, 1991

[22] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[23] McBride-Limaye, 1988

[24] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[25] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[26] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[27] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[28] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[29] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[30] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[31] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[32] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[33] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[34] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[35] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[36] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[37] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[38] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[39] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[40] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[41] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[42] Cypess, 1991

[43] Cypess, 1991

[44] Cypess, 1991

[45] Cypess, 1991

[46] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[47] Cypess, 1991

[48] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[49] Hinojosa, 2013

[50] Hinojosa, 2013

[51] Hinojosa, 2013

[52] Hinojosa, 2013

[53] Hinojosa, 2013

[54] Del Castillo, 2013

[55] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[56] Cypess, 1991

[57] Del Castillo, 2013

[58] Del Castillo, 2013

[59] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[60] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[61] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[62] Del Castillo, 2013

[63] Cypess, 1991

[64] Del Castillo, 2013

[65] Del Castillo, 2013

[66] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

[67] Del Castillo, 2013

[68] Del Castillo, 2013

[69] Del Castillo, 2013

[70] Cypess, 1991

[71] Hinojosa, 2013

[72] “La Malinche Betrays the Aztecs: 1519–1524”, 2014

The post La Malinche – The Princess who helped bring down the Aztec Empire appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 18, 2023

Book News Week 47

Book news week 47: 20 November – 26 November 2023

Empire of God: How the Byzantines Saved Civilization

Hardcover – 21 November 2023 (US)

The post Book News Week 47 appeared first on History of Royal Women.