Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 23

February 11, 2025

Book Review: Rasputin’s Killer and his Romanov Princess by Coryne Hall

Princess Irina Alexandrovna of Russia was born on 15 July 1895 as the daughter of Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich of Russia and Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna of Russia, making her the niece of Emperor Nicholas II of Russia. She married the very wealthy Prince Felix Yusupov in 1914. He would later become best known for his role in the killing of Grigori Rasputin, a healer who had considerable influence on Nicolas II and his family. For this, he was put under house arrest.

Rasputin’s Killer and his Romanov Princess by Coryne Hall covers the lives of this fascinating couple as they navigate through the scandal of Rasputin’s killing and the eventual downfall of the empire built by the Romanovs. During their time in exile, they were plagued by financial difficulties and lawsuits. Despite these financial difficulties, they were known for their generosity. Their marriage had its ups and downs, but they remained married until Felix’s death in 1967. Irina survived him for three years. Their only child, also named Irinia, married Count Nikolai Dmitrievich Sheremetev, and their only child is still living today.

Rasputin’s Killer and his Romanov Princess is an excellent read for those interested in the Romanovs. This couple witnessed the downfall and lived through the aftershocks. The book has a nice flow and is easy to follow. I’d highly recommend it.

Rasputin’s Killer and his Romanov Princess by Coryne Hall is available now in the UK and the US.

The post Book Review: Rasputin’s Killer and his Romanov Princess by Coryne Hall appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 9, 2025

Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai – The King of Dai’s faithful Imperial Consort who committed suicide so she wouldn’t have to marry her brother

Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai was originally a Princess of Jin.[1] She married the King of Dai and became his Imperial Consort.[2] In 475 B.C.E., Duke Zhao Xiangzi of Jin (Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai’s younger brother) killed her husband and annexed the State of Dai.[3] Duke Xiangzi of Jin wanted to marry his older sister, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai, and make her his duchess.[4] Thus, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai was forced to make a difficult decision.[5] Her decision would be praised by Chinese historians for thousands of years.[6]

In circa 490 B.C.E., Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai was born.[7] She lived during the Spring and Autumn era (which lasted from 771 to 453 B.C.E).[8] During this period, Chinese states were declaring their own independence from the ruling Zhou Dynasty to form their own dynasties.[9] Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai was a Princess of Jin.[10] Her father was Duke Zhao Jiangzi of Jin.[11] She had a younger brother named Prince Zhao Xiangzi.[12] She married the King of Dai (modern-day Zhejiang Province) and became his Imperial Consort.[13]

In 475 B.C.E., Duke Zhao Jiangzi of Jin died.[14] Prince Zhao Xiangzi became the next Duke of Jin.[15] He decided to annex the small State of Dai.[16] Duke Zhao Xiangzi of Jin murdered Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai’s husband.[17] Then, he raised an army and invaded the State of Dai.[18] Duke Zhao Xiangzi of Jin wanted to take his older sister, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai, back to Jin and make her his duchess.[19] However, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai refused.[20] She said:

“Now Dai has been extinguished, but how can I return home? I have heard that a wife’s righteousness comes from not having two husbands. How could I have two husbands then? It is not right for me to either insult my husband with my younger brother or insult my younger brother with my husband. I dare not cause resentment and hence can not return.”[21]

Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai wept and “called up to Heaven.”[22] Then, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai committed suicide by stabbing herself with a hairpin.[23] Imperial Consort Zhao died in 475 B.C.E.[24] The people of Dai admired her act of remaining faithful to her husband, and she became well-loved by her people.[25]

Ancient chroniclers did not criticize Duke Xiangzi of Jin “for wanting to commit incest with his sister”, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai.[26] Instead, they praised Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai’s faithfulness to her husband, the King of Dai.[27] She is also praised for not showing any anger toward her brother for his ruthless deeds.[28] For thousands of years, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai has been the model of “chastity and propriety.”[29] In Biographies of Eminent Women, Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai has been categorized under “Biographies of the Chaste and Righteous.”[30]

Sources:

Cook, C. A. (2015). “Zhao, Wife of the King of Dai”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 92-93.

Eno, R. (2010). 1.7. Spring and Autumn China (771-453). Indiana University, PDF.

Liu, X., Kinney, A. B. (2014). Exemplary Women of Early China: The Lienü Zhuan of Liu Xiang. United Kingdom: Columbia University Press.

[1] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[2] Cook, 2015

[3] Cook, 2015; Liu and Kinney, 2014

[4] Cook, 2015

[5] Cook, 2015

[6] Cook, 2015

[7] Cook, 2015

[8] Eno, 2010

[9] Eno, 2010

[10] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[11] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[12] Cook, 2015

[13] Cook, 2015

[14] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[15] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[16] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[17] Cook, 2015

[18] Cook, 2015

[19] Cook, 2015

[20] Cook, 2015

[21] Cook, 2015, p. 93

[22] Cook, 2015, p. 93

[23] Cook, 2015; Liu and Kinney, 2014

[24] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[25] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[26] Cook, 2015, p. 93

[27] Cook, 2015

[28] Cook, 2015

[29] Cook, 2015, p. 93

[30] Cook, 2015, p. 93

The post Imperial Consort Zhao of Dai – The King of Dai’s faithful Imperial Consort who committed suicide so she wouldn’t have to marry her brother appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 8, 2025

Book News Week 7

Book News week 7 – 10 February – 16 February 2025

The Rebel Romanov

Hardcover – 13 February 2025 (UK)

The Book of Awesome Asian Women: Empresses, Warriors, Scientists, and Mavericks

Paperback – 11 February 2025 (US)

The post Book News Week 7 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Queen Sālote Tupou III – Lavinia Veiongo Fotu: The embodiment of good nature

The future Queen Sālote Tupou III of Tonga would not know her mother as she died when Sālote was just two years old.

Lavinia Veiongo Fotu was born on 9 February 1879 as the daughter of ʻAsipeli Kupuavanua Fotu and Tōkanga Fuifuilupe. She was named for her paternal grandmother, Old Lavinia, who was the daughter of the last Tuʻi Tonga (line of Kings) Laufilitonga.

Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu – Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18990630-02-03

Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu – Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18990630-02-03King George Tupou II of Tonga was meant to marry Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu in 1899, and all the preparations had already been made when he changed his mind and chose to marry Lavinia. Both ʻOfakivavaʻu and Lavinia were of aristocratic blood of the Tu’i Tonga, although Lavinia was only descended from that line through her father. Her maternal line could not be traced further back than two generations. This choice went against the nobles who initially voted overwhelmingly in favour of ʻOfakivavaʻu. George’s continued insistence on Lavinia eventually led to them caving.

On 1 June 1899, the European-style celebration of the wedding took place. George wore a blue uniform laced with gold and medals. He also wore a crimson mantle. Lavinia wore a wedding gown of satin, a veil and orange blossoms, and she was accompanied by six bridesmaids who also wore satin. After a choir had sung the wedding anthem, George placed a diadem on Lavinia’s head and declared her Queen of Tonga.1

A few days later, the Tongan wedding ceremony (tu’uvala) was held. This included exchanges of property between the chiefly families who were part of the alliance. The family of ʻOfakivavaʻu was not present for either wedding ceremony, and the animosity would remain for many years to come. In the weeks after the wedding, it was rumoured that Lavinia had not left the palace since her wedding day in fear of her safety.2 Songs were a traditional form of protest. In August 1899, the press reported, ” Scurrilous songs reflecting on Her Majesty are of almost daily publication. The average Tongan is actually a poet, and his genius displays itself nowhere more acutely than in the composition of insulting songs. These are sung by almost everybody and care is especially taken that copies shall reach the Palace by secret means to the annoyance of their Majesties.”3

Lavinia on her wedding day (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18990811-07-02)

Lavinia on her wedding day (Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18990811-07-02)Lavinia quickly fell pregnant, and her first, and as it would turn out only, child was born on 13 March 1900. Sālote’s birth was announced with a 13-gun salute. She was baptised on 10 June in the Royal Chapel as Sālote Mafile‘o Pilolevu.

Sir Basil Thomson, a colonial administrator, later wrote, “I was taken upstairs to see Queen Lavinia and the infant Princess. In a clean and well-furnished modern bedroom, I found Her Majesty, Kubu’s daughter, dressed in a loose European wrapper. A girl brought in the baby princess – a big, brown infant three weeks old. She slept peacefully throughout the interview and throughout the kiss I imprinted upon the royal forehead, which salute seemed to please the royal parents very much. She was the first princess, and the last, that I have ever kissed.”4

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19000824-04-08

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19000824-04-08ʻOfakivavaʻu herself had no part in the animosity against the King and Queen. She even danced at the celebrations for George’s 27th birthday in 1901. However, when she contracted tuberculosis and died in December 1901, it was claimed that she died from the distress of the King’s rejection. Lavinia had visited ʻOfakivavaʻu during her illness and also attended her funeral. She may have caught the tuberculosis that would also kill her from ʻOfakivavaʻu but she had been in delicate health since her daughter’s birth.

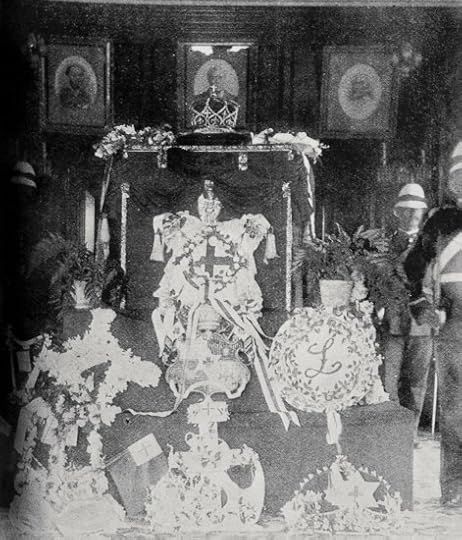

Queen Lavinia died on 24 April 1902 at the palace. George was deeply affected by her death, and he honoured her with an immense funeral. She lay in state for four days and was buried at the royal cemetery of Mala’e Kula.

The Sydney Morning Herald wrote of Lavinia, “The late queen was the embodiment of good nature and persons of all ranks were assured of a kind and courteous reception at her hands. She even caused Tupou to be a little more attentive to his duties in the matter of the reception of higher chiefs who, in the King’s absence, she would in no wise permit to depart before interviewing Tupou for whom she would send if necessary.”5

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19020612-05-04

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19020612-05-04The post The Year of Queen Sālote Tupou III – Lavinia Veiongo Fotu: The embodiment of good nature appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 7, 2025

Princess Ruth Keʻelikōlani – A wayward Princess

Princess Ruth Keʻelikōlani was likely born on 9 February 18261 as the daughter of High Chiefess Pauahi, a widow of King Kamehameha II, who was also her uncle.

Keʻelikōlani’s birthplace (Hawaiʻi State Archives)

Keʻelikōlani’s birthplace (Hawaiʻi State Archives)Her mother married Mataio Kekuanaoa, and he recognised her as his daughter. Her father could have also been Kahalaia, who had comforted her during her husband’s absence. Tragically, Pauahi died of complications following a long and painful labour. Keʻelikōlani’s paternity and even her birthdate remain a question of debate. Keʻelikōlani herself celebrated her birthday on 9 February.

Keʻelikōlani’s father remarried the following year to another one of King Kamehameha II’s widows, Elizabeth Kīnaʻu, who was also the King’s half-sister. This marriage would produce three sons and a daughter before Kīnaʻu’s death in 1839. Keʻelikōlani was being raised in the house of Lilia Nāmāhāna under the guardianship of Queen Ka’ahumanu. The Queen died when Keʻelikōlani was six years old, and Keʻelikōlani went to live with her father and his second wife. Kīnaʻu treated Keʻelikōlani like one of her own children.

Shortly before her 16th birthday, Keʻelikōlani married William Pitt Leleiohoku I. He was the same age but had been married once before to Nāhiʻenaʻena. He had been only ten at the time. This time, it was a love match, and they went on to have two sons together: William Pitt Kīnaʻu and a son who died in infancy. Leleiohoku died in an epidemic of measles and dysentery at the age of just 22. Keʻelikōlani was heartbroken, but she inherited a lot of land from her husband. She also became the Governor of Hawai’i while raising her son. Tragedy would strike again in 1859 when Kīnaʻu died in an accident at the age of 16.

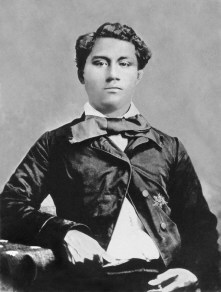

William Pitt Kīnaʻu (Hawaiʻi State Archives)

William Pitt Kīnaʻu (Hawaiʻi State Archives)In 1856, Keʻelikōlani remarried to Isaac Young Davis, a grandson of Isaac Davis, who had been captured by King Kamehameha the Great in 1790. He was two years older than Keʻelikōlani and very tall. However, their marriage was soon unhappy. Their son, Keolaokalani Davis, was born in 1862 and was hānai (adopted) against his father’s wishes to Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop. Even her half-brother, the future King Kamehameha V, was against the adoption. He said, “You must go back and tell my sister that on no account is she to give that child to another. I am an adopted child myself, deprived of the love of my mother, and yet I was a stranger in the house of my adoption.”2

It was said that Isaac had hit Keʻelikōlani on the nose during a bad argument. The nose became badly infected, and even an operation could not stop it from disfiguring her. They separated after one year of marriage, although they clearly reunited at least once to conceive their son. They finally divorced in 1868. Their son died at the age of six months.

Keʻelikōlani hānai (adopted) William Pitt Kalahoʻolewa shortly after his birth and legally adopted him in 1862. He was the son of Analea Keohokālole and Caesar Kapaʻakea and a younger brother of Queen Liliʻuokalani and King Kalākaua. Keʻelikōlani renamed him Leleiohoku after her first husband and made him the legal heir to her estate. Despite Keʻelikōlani’s own unwillingness to speak English or convert to Christianity, her adopted son had a modern education. He became the heir to his childless brother but tragically died of pneumonia, which he had contracted while studying in California. He was still only 22 years old.

Keʻelikōlani was described by an English woman named Sophia Cracroft during a visit in 1861. She wrote, “She wore shoes and stockings but nothing on her head, her dark wavy hair being gathered up behind. She was of the usual dark brown complexion but certainly the ugliest as well as the fattest woman we have seen in the land. In general, they have good noses, but hers was quite the exception’ it looks as if the bridge and upper part of the nostrils must have been broken in, as all that part is literally even with her face. (Since writing the above we learn that she has an operation for disease in the nose, which is the cause of the deformity). As to size, she is perfectly enormous with fat and her gait is a mixture of waddle and stately swing remarkable to behold.”3 Twelve years later, another woman wrote, “Her size and appearance are most unfortunate, but she is said to be good and kind.”4

Keʻelikōlani was once considered a possible heir to the throne. Her half-brother, King Kamehameha V, died without naming an heir in 1872, but a few months later, Lunalilo, a grandnephew of King Kamehameha I, was elected as the new King. Perhaps they considered her unclear genealogy. During the election, U.S. Minister Henry A. Pierce wrote that Keʻelikōlani was “… a woman of no intelligence or ability.”5 Nevertheless, Keʻelikōlani inherited vast estates from her half-brother, which she managed until her death. The new King reigned for just over a year before dying of tuberculosis aggravated by alcoholism. He, too, left no children. King Kalākau, Keʻelikōlani’s adopted son’s half-brother, was chosen to succeed him.

After the death of her adopted son, Keʻelikōlani was heartbroken, and she became bitter. One of her bookkeepers later wrote, “The outstanding thing about Princess Ruth was her temper… it was something awful. She wouldn’t stop short of picking up a calabash and flinging it at her retainers. Her poor servants caught plenty of abuse when she took to one of her tantrums and got her hair in a snarl, which was often. I have seen her pick up a buggy-whip and give anyone within reach a cowhiding…”6

After losing so many loved ones, she threw herself into her business matters. Her tenure as governor had ended in 1874, but her vast estates were still in place to manage.

Perhaps one of the most famous acts in her life came in 1881 when the town of Hilo was being threatened by lava. A group of citizens came to Keʻelikōlani, asking her to intercede with Pele, the Goddess of Volcanoes. Keʻelikōlani headed their call and travelled to the edge of the lava on the night of 9 August 1881. The following morning, the flow of the lava had stopped. The people rejoiced, but the missionaries on the island attempted to attribute the miracle to Christian prayers and, so Keʻelikōlani’s story was largely suppressed.

By then, Keʻelikōlani was already in the twilight of her life. Shortly after her adventure at Hilo, she began building a magnificent palace, which was completed on her last birthday. She never got to enjoy it. Shortly after the completion, she travelled to Kailau for her health. At the Hulihe’e Palace, she took to her bed in a grass hut on the grounds. Many concerned Hawaiians came to visit her as she lay propped up on pillows. Her breathing became laboured as her fever rose. King Kalākau visited her on 23 May 1881, but he was assured that her illness was not serious.

Keʻelikōlani was close to her cousin, Bernice Pauahi Bishop, and she had rushed to Keʻelikōlani’s side to care for her. Keʻelikōlani knew she was dying and wrote her own farewell lament. Keʻelikōlani died at 9 in the morning on 24 May 1883 at the age of 57. She had altered her will in January, leaving the majority of her estate to Bernice. Keʻelikōlani’s funeral took place on 17 June. For many, Keʻelikōlani had been the last link to the old Hawaiian ways.

Bernice wrote shortly after Keʻelikōlani’s death, “It was not altogether unexpected but still it came like a shock to me, when it did come. I miss greatly, as a mother misses a child she has watched over, and cared for during illness. So have I missed mine, for she was like a child in many ways, so careless and wayward, and she was the last nearest relative I had…”7

The post Princess Ruth Keʻelikōlani – A wayward Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 6, 2025

Princess Claire’s Diamond Tiara

The future Princess Claire of Belgium wore this small diamond tiara for her wedding to Prince Laurent of Belgium.

It is unclear where the diamond tiara originated from, but it was a wedding gift to Claire from her new parents-in-law, King Albert and Queen Paola.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesAfter the wedding, Claire continued to wear the tiara for events, such as the wedding of Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark to Mary Donaldson. For a while, this was Claire’s only tiara. She has since gained a second tiara with diamonds and pearls.

The post Princess Claire’s Diamond Tiara appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 4, 2025

Book Review: Thorns in the Crown: The Story of the Coronation and what it Meant for Britain by Barry Turner

*review copy*

The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 marked the start of a new Elizabethan era, but the country was still grappling with the aftereffects of the Second World War.

Thorns in the Crown: The Story of the Coronation and What It Meant for Britain by Barry Turner is the story of the United Kingdom around the time of the coronation and how it got there.

I found the book interesting, to begin with, but it soon became rather long-winded. The coronation itself is only a short part of the book, and I was left wondering what the point of this book was supposed to be. There were parts of the book where the tone was a bit too snippy for my liking.

Overall, I’m not sure if this was the book for me.

Thorns in the Crown: The Story of the Coronation and What It Meant for Britain by Barry Turner is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Book Review: Thorns in the Crown: The Story of the Coronation and what it Meant for Britain by Barry Turner appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 2, 2025

Imperial Consort Yue Ji of Chu – King Zhao of Chu’s Imperial Consort who willingly died with him

Imperial Consort Yue Ji of Chu was the daughter of King Goujian of Yue. She was the Imperial Consort to King Zhao of Chu. One day King Zhao of Chu asked if Imperial Consort Yue Ji would die with him.[1] However, she refused.[2] This cost her the love of her husband.[3] When King Zhao of Chu proved himself an honourable King, Imperial Consort Yue Ji finally agreed to die with him.[4] Ancient chroniclers have constantly praised her for her “loyalty.”[5]

Imperial Consort Yue Ji of Chu was born in the early fifth century B.C.E.[6] She lived during the Spring and Autumn era (which lasted from 771 to 453 B.C.E.).[7] During this period, Chinese states were declaring their own independence from the ruling Zhou Dynasty to form their own dynasties.[8] She was a Princess of Yue (modern-day Zhejiang Province).[9] Her father was King Goujian of Yue.[10] She married King Zhao of Chu (who reigned from 515-488 B.C.E.).[11] She became his Imperial Consort. King Zhao of Chu also had another wife who was also his Imperial Consort named Cai Ji.[12]

During the early years of King Zhao of Chu’s marriages to both Imperial Consort Yue Ji and Imperial Consort Cai Ji, he would often take his wives on pleasure outings.[13] During one pleasant outing, King Zhao of Chu asked his wives if they would die with him since he was fond of their time together.[14] Imperial Consort Cai Ji immediately swore that she would die with him.[15] However, Imperial Consort Yue Ji refused to swear and said that he hadn’t proved himself a “virtuous man in government”[16] that made it worth dying with him.[17] King Zhao was surprised but respected her decision.[18] Yet, her refusal made him prefer Imperial Consort Cai Ji over her.[19] Imperial Consort Yue Ji bore King Zhao of Wu a son named Prince Xiongzhang (the future King Hui of Chu who reigned from 488-432 B.C.E).[20]

In 488 B.C.E., King Zhao of Chu had become mortally ill during a military campaign.[21] He refused to allow his generals and ministers to sacrifice themselves in his place.[22] King Zhao of Chu’s decision greatly impressed Imperial Consort Yue Ji.[23] She was finally willing to die with him because of his “righteousness.”[24] When King Zhao of Chu died, Imperial Consort Yue Ji committed suicide.[25] Imperial Consort Cai Ji refused to commit suicide.[26] King Zhao of Chu’s brothers were very impressed with Imperial Consort Yue Ji’s action of suicide.[27] Because of her loyalty to her husband, they chose Imperial Consort Yue Ji’s son, Prince Xiongzhang, as the next King of Chu.[28] Prince Xiongzhang ascended the throne as King Hui of Chu.[29]

Imperial Consort Yue Ji of Chu was reluctant to die with King Zhao of Chu.[30] Her reluctance lessened King Zhao of Chu’s love for her.[31] Instead, he preferred Imperial Consort Cai Ji over her.[32] King Zhao of Chu had to prove himself to be a righteous king before she could die with him.[33] Once King Zhao of Chu made an honourable act as king, Imperial Consort Yue Ji willingly died with him.[34] Because of her act of faithfulness, her son became the next King of Chu.[35] In Biographies of Eminent Women, Imperial Consort Yue Ji of Chu’s biography is categorized under “Biographies of the Chaste and Righteous.”[36]

Sources:

Cook, C. A. (2015). “Yue Ji, Wife of King Zhao of Chu”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 90-91.

Eno, R. (2010). 1.7. Spring and Autumn China (771-453). Indiana University, PDF.

Liu, X., Kinney, A. B. (2014). Exemplary Women of Early China: The Lienü Zhuan of Liu Xiang. United Kingdom: Columbia University Press.

[1] Cook, 2015

[2] Cook, 2015

[3] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[4] Cook, 2015

[5] Cook, 2015, p. 90

[6] Cook, 2015

[7] Eno, 2010

[8] Eno, 2010

[9] Cook, 2015

[10] Cook, 2015

[11] Cook, 2015

[12] Cook, 2015

[13] Cook, 2015

[14] Cook, 2015

[15] Cook, 2015

[16] Cook, 2015, p. 90

[17] Cook, 2015

[18] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[19] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[20] Cook, 2015

[21] Cook, 2015

[22] Cook, 2015

[23] Cook, 2015

[24] Cook, 2015, p. 90

[25] Cook, 2015

[26] Cook, 2015

[27] Liu and Kinney, 2014, Cook 2015

[28] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[29] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[30] Cook, 2015

[31] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[32] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[33] Cook, 2015

[34] Cook, 2015

[35] Cook, 2015

[36] Cook, 2015, p. 90

The post Imperial Consort Yue Ji of Chu – King Zhao of Chu’s Imperial Consort who willingly died with him appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 1, 2025

Book News Week 6

Book News Week 6 – 3 February – 9 February 2025

Captive Queen: The Decrypted History of Mary, Queen of Scots

Hardcover – 4 February 2025 (US)

The Lives and Deaths of the Princesses of Hesse: The curious destinies of Queen Victoria’s granddaughters

Hardcover – 4 February 2025 (US)

The Kings and Queens of England

Paperback – 6 February 2025 (UK)

The post Book News Week 6 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 31, 2025

Taking a look at Princess Stéphanie of Monaco as she turns 60

Princess Stéphanie of Monaco was born on 1 February 1965 as the youngest daughter of Rainier III, Prince of Monaco and Princess Grace (born Grace Kelly). She had two elder siblings, Caroline and Albert, and her mother had suffered two miscarriages. Shortly after her birth, Grace told a friend, “She’ll have everything she wants.” 1 The following month, Stéphanie was christened at the Cathedral of Monaco with the name Stéphanie Marie Elisabeth.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesAs the successor, Albert spent a lot of time with his father, while the two sisters were mostly paired off with their mother. The children also had a nanny each, but Stéphanie had trouble keeping them. She had once had six in a single year, and her mother complained, “I really can’t blame them for quitting. Stéphanie is so bossy. I hardly know what to do about her myself.” 2 In 1974, Grace, Caroline and Stéphanie moved into an apartment in Paris, mostly to curtail Caroline, who had enrolled in school there. They became daily targets of the paparazzi, and their relationship suffered during this time.

Embed from Getty ImagesStéphanie began her education in Monaco at the Les Dames de St.-Maur convent school while she also attended ballet lessons at Marika’s Academie. During her teenage years, she was quite the rebel, often leaving her parents frustrated. Nevertheless, her mother said in an interview, “Caroline is perhaps more literary, Stéphanie more mathematical. Both are warm, bright, amusing, intelligent and capable girls. They’re very much in tune with their era. Besides being good students, they are good athletes – excellent skiers and swimmers. Both can cook and sew, play the piano, and ride a horse. But, above all, my children are good at sports, conscious of their position, and considerate of others. They are sympathetic to the problems and concerns in the world today.” 3 Later, Stéphanie also attended the Institute St. Dominique in Paris.

At the age of 16, Stéphanie began to hit the tabloids with her relationships, much to her mother’s frustration. Her school results suffered, and she was about to be held back a year when her parents decided to transfer her to a different school. She graduated in the spring of 1982. Tragedy struck that September.

On 13 September, Stéphanie and Grace left the house at Roc Agel around 9.45 a.m. Grace drove down the narrow road with Stéphanie in the passenger seat. The car went down the extremely curvy Route D 37, with several sharp hairpin turns after each other. Grace suddenly suffered a cerebral haemorrhage while at the wheel of the car, and the car began to skid and skirt along the rock wall. Then, the car sped down the hill, heading towards the next hairpin turn without slowing down. The car plunged off the 130-foot cliff and came to rest between the trees and bushes of a private garden. Stéphanie managed to crawl out of the car and begged the people who ran toward them to call for help. Grace was sprawled across the inside of the car with her head towards the rear. One of her legs appeared to be twisted; she was unconscious and had a headwound. Emergency personnel managed to extract her from the car, and she was transported to her namesake hospital. Stéphanie was transported in the second ambulance. Prince Rainier and Prince Albert reached the site shortly before 10.30 a.m. and saw how Grace and Stéphanie were being loaded into the ambulances.

Embed from Getty ImagesWhile Stéphanie remained unaware of what was happening, Prince Rainier, Prince Albert and Princess Caroline were living a nightmare. Doctors were finally able to give Prince Rainier a full update on his wife’s condition. Her brain damage was severe and permanent – there was no longer any brain function present. Princess Grace was now in a coma and being kept alive by machines. From the early hours of the morning of 14 September, she was clinically dead. Rumours began to circulate around the accident that Princess Stéphanie had been the one driving or that the brakes had failed. Stéphanie herself was injured in the accident, which would have made it impossible to switch places with her mother. In addition, she always denied the rumours. Friends of the family also said that Grace would never have allowed Princess Stéphanie to drive. Stéphanie could not attend the funeral as she was still hospitalised.

After her mother’s death, Stéphanie’s life generated even more controversy, with each new beau being labelled as the “new chosen one.” 4 Against her father’s wishes, she signed a modelling contract and became a swimwear designer. Then, she became a recording artist.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesIn May 1992, Stéphanie announced that she was pregnant by Daniel Ducuet, a former palace guard. She gave birth to a boy named Louis on 26 November 1992. Her family did not visit her in the hospital, but whatever was going on was soon fixed. On 4 May 1994, a daughter named Pauline was born. Stéphanie and Daniel were finally married on 1 July 1995, legitimising their two children. However, they were divorced in October 1996. Daniel later said in an interview, “I have betrayed my wife, I have betrayed her love, and I have betrayed my children.” 5 On 15 July 1998, Stéphanie gave birth to a third child – a daughter named Camille Gottlieb. She is not in the line of succession.

Stéphanie ran off with an Italian circus performer in 2001 but returned to Monaco in 2002. On 12 September 2003, Stéphanie married Portuguese acrobat Adans Lopez Peres, but this marriage ended in divorce the following year.

Embed from Getty ImagesIn 2003, she founded the Women Face the AIDS Association, which became Fight AIDS Monaco in 2004. In 2006, she became a Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) ambassador. She became a grandmother in 2023 when her son Louis became the father of a daughter named Victoire.

The post Taking a look at Princess Stéphanie of Monaco as she turns 60 appeared first on History of Royal Women.