Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 21

March 8, 2025

Book News Week 11

Book News Week 11 – 10 March – 16 March 2025

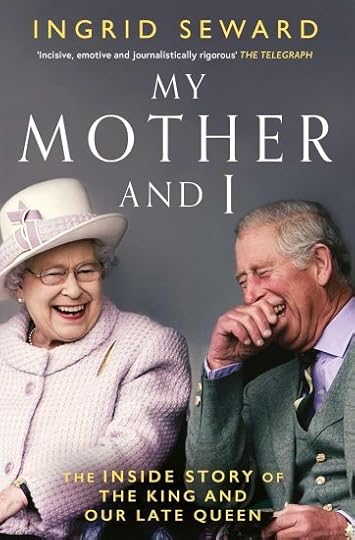

My Mother and I

Paperback – 13 March 2025 (UK)

The Book of Awesome Asian Women: Empresses, Warriors, Scientists, and Mavericks

Paperback – 11 March 2025 (UK)

The post Book News Week 11 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 7, 2025

Countess Palatine Sabina of Simmern – The Bones of a Countess

Countess Palatine Sabina of Simmern was born in Simmern on 13 June 1528 as the daughter of John II, Count Palatine of Simmern and Beatrix of Baden. She was their tenth and penultimate child.

Following the death of her mother in 1535, she was taken in by her relative, the future Frederick II, Elector Palatine, and his wife, Dorothea of Denmark. Dorothea was a niece of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

On 8 May 1544, Sabina married Lamoral, Count of Egmont, in Speyer. This marriage had been arranged, among others, by Emperor Charles and happened during the Imperial Diet. This meant that the wedding was attended by the Emperor, several members of his family and other German nobility. Following their wedding, the newlyweds settled in Brussels. Sabina became a part of the court of Charles’s sister Mary. Over the years, she gave birth to 13 children, eight daughters and three sons of whom survived to adulthood.

Sabina saw her family again when her brother became Frederick III, Elector Palatine. Sabina and her husband travelled to Heidelberg to celebrate this, but Sabina was pregnant, so the visit didn’t last very long. There was also a political element; King Philip II of Spain had requested that Lamoral bring Frederick his best wishes in order to improve his relationship with the electors. However, Frederick supported Calvinism, which caused a rift with the Habsburgs. Sabina and Lamoral had remained loyal to the Catholic faith, and Sabina also had limited contact with her siblings because of this.

At the court in Brussels, Sabina reportedly had a rivalry with Anna of Saxony, Princess of Orange. There were rifts over who had precedence, which reportedly escalated to such an extent that the women pushed through a door at the same time as neither would yield to the other.1 Nevertheless, Sabina still danced with Anna’s husband at the wedding of Alexander Farnese and Maria of Portugal while Lamoral danced with Anna.

Sabina begs the Duke of Alba for mercy (RP-P-OB-79.046 public domain via Rijksmuseum)

Sabina begs the Duke of Alba for mercy (RP-P-OB-79.046 public domain via Rijksmuseum)Sabina’s life as she knew it came to a crashing halt in 1567 when her husband was arrested by the Duke of Alba on charges of high treason. Sabina tried to use every connection she had to free him. She even wrote a threatening letter to King Philip II, telling him that he would not prefer it if she sought help abroad.

On 31 March 1568, she wrote to the Duke of Alba, “The Countess of Egmont very humbly shows that she has heard that the Lord Count of Egmont, her husband, is in a pitiful condition and is in danger of falling into a serious illness which may be caused by him as he has been kept in a room for four or five months and therefore cannot be in the open air. Therefore, I request your Highness, in order to avoid any greater difficulty, to grant the said Lord Count the freedom to walk in the fresh air around the castle of Ghent and to allow Lord Jacob, his physician who knows his body well, to visit and heal him and that one of his servants who is staying in the castle be allowed to bring his meat without having to be passed from hand to hand.”2 She also claimed that her husband, as a knight in the Order of the Golden Fleece, had special rights.

After hearing he was to be sentenced to death, he wrote to her about how much he loved her and that she should take care of their children.3 He also wrote to King Philip II of Spain asking him not to let his dear wife and children suffer under disapproval or confiscation.4

In the end, it was no use. On 5 June 1568, Lamoral was executed on the Grand Place in Brussels. Sabina had retreated to a convent with her children after her husband’s arrest. All his goods had been confiscated, and she was left destitute. Even the Duke of Alba felt sorry for her, and he arranged for King Philip II to grant her an allowance. Lamaoral’s remains were brought to Zottegem, where they were interred in the church. It wasn’t until 1576 that the confiscated goods were returned to Sabina.

Sabina devoted these years to caring for her children. One of her sons, Philip, was captured by the Spanish in 1575, and it was Sabina who fought to have him released. Several of her daughters became nuns. Her three sons all eventually succeeded as Count of Egmont in turn.

Sabina died in Antwerp on 19 July 1578, and she was interred alongside her husband in Zottegem.

Click to view slideshow.Their coffins were rediscovered by accident in 1804. Along with the coffins of Lamoral and Sabina, three heart-shaped lead boxes were found; these contained the embalmed hearts of Lamoral, as well as sons Philip and Charles.

Click to view slideshow.The coffins were transferred to the new crypt underneath the church in 1857. During renovations in 1951, the coffins were opened, and the skeletons and hearts were researched. The bones were given special treatment to preserve them, and they were reinterred in 1954. They now lie in sarcophagi with a transparent top so that the bones can be seen. The hearts remained in an archive until 2008 but are now in the Town Hall across the street from the crypt. Their boxes are on display in the crypt. The Town Hall also houses Sabina’s original coffin plate and a lock of her hair. It also has one of Lamoral’s vertebrae, which was damaged during his execution, in a display case. In 2016, the glass dome was added.5

You can visit the crypt by picking up the key at the Town Hall in Zottegem.

The post Countess Palatine Sabina of Simmern – The Bones of a Countess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 6, 2025

The Brabant Laurel Wreath Tiara

The Brabant Laurel Wreath Tiara was given to future Queen Mathilde of Belgium as a wedding gift in 1999 by a group of Belgian aristocrats.

Embed from Getty ImagesMathilde was part of the Belgian nobility by birth and she became Duchess of Brabant when she married the then Prince Philippe. The Brabant Laurel Wreath Tiara was the only tiara she had for her use until she became Queen. She owns it personally.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe tiara was made by Hennel & Sons in 1912, and it can also be converted into a necklace.

Embed from Getty ImagesEven though Queen Mathilde now has more tiaras for her use, she has continued to wear this much-loved piece.

The post The Brabant Laurel Wreath Tiara appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Meghan Markle or Meghan Sussex?

The Duchess of Sussex has been the subject of ridicule again after claiming her name is no longer Meghan Markle on her new show on Netflix but rather Meghan Sussex. So what is going on?

Markle is indeed the Duchess’s maiden name and should no longer be used. As a member of the royal family, she does not need a surname, but where one is required, the name Mountbatten-Windsor can be used. This is the official surname.

However, it has been the practice of other members of the royal family, and also members of the peerage, to use their title as a surname. Therefore, it is within royal protocol for the Duchess of Sussex to use the name Meghan Sussex. For example, her brother-in-law used the name “Wales” during his time in the army.1

This was also confirmed by Debrett’s in a post on X.

The official surname of the Royal Family is Mountbatten-Windsor. It has long been the practice of the Royal Family, and indeed the peerage, to use a title as a surname where one is available. It is perfectly within protocol for the Duchess to use Meghan Sussex.

— Debrett’s (@Debretts) March 6, 2025

She has not “changed” her name; she hasn’t been Meghan Markle since she married Prince Harry.

This may be superfluous, but this is your reminder that the Sussexes have not been stripped of their titles. It was announced that the Duke and Duchess would not use the style of HRH, but they still retain the style.2

The post Meghan Markle or Meghan Sussex? appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 4, 2025

Princesses & Twins (Part one)

Giving birth has always been dangerous, but multiples added another dimension to the danger. Nevertheless, there are several instances of surviving twins. Here are some royal twins (girl/girl) from history.

Elsa of Württemberg & Olga of Württemberg

Vera with her daughters (public domain)

Vera with her daughters (public domain)Elsa and Olga were born on 1 March 1876 as the daughters of Duke Eugen of Württemberg and Grand Duchess Vera Constantinovna of Russia. Elsa was the elder twin. Their only sibling died at the age of seven months. The sisters were said not to look alike.

Elsa went on to marry Prince Albert of Schaumburg-Lippe on 6 May 1897, and they had four children together: Max (born 1898), Franz Joseph (born 1899), Alexander (born 1901) and Bathildis (born 1903). She died on 27 May 1936.

Olga went on to marry Prince Maximilian of Schaumburg-Lippe, who happened to be her brother-in-law’s younger brother, on 3 November 1898. They had three children before Maximilian’s death in 1904: Eugen (born 1899), Albert (born 1900) and Bernhard (born 1902-died young). Olga died on 21 October 1932.

Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria & Amalie Auguste of Bavaria

Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria & Amalie Auguste of Bavaria (public domain)

Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria & Amalie Auguste of Bavaria (public domain)Elisabeth Ludovika and Amalie Auguste were born on 13 November 1801 as the daughters of the future King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria and Caroline of Baden. They were actually the first of two sets of twins born to this couple.

Elisabeth Ludovika went on to marry the future King Frederick William IV of Prussia on 29 November 1823, but they did not have any children together. She died on 14 December 1873.

Amalie Auguste went on to marry the future John, King of Saxony, on 21 November 1822. They had nine children together, of which six survived to adulthood: Albert (born 1828), Elisabeth (born 1830), George (born 1832), Anna (born 1836), Margaretha (born 1840) and Sophie (born 1845). She died on 8 November 1877.

Maria Anna of Bavaria & Sophie of Bavaria

Maria Anna of Bavaria & Sophie of Bavaria (public domain)

Maria Anna of Bavaria & Sophie of Bavaria (public domain)Maria Anna of Bavaria & Sophie of Bavaria were the second set of twins born to the future King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria and Caroline of Baden. They were born on 27 January 1805.

On 4 November 1824, Sophie married Archduke Franz Karl of Austria. They went on to have four surviving sons together, including the future Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. She died on 28 May 1872.

Maria Anna went on to marry the future King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony on 24 April 1833. Her sister, Amalie Auguste, was married to Frederick’s brother, John. Maria Anna and Frederick did not have any children together. She died on 13 September 1877.

Aisha bint Al Faisal & Sara bint Al Faisal

Aisha and Sara are the twin daughters of Prince Faisal bin Hussein, the younger brother of King Abdullah II of Jordan, and Princess Alia Tabbaa. They were born on 27 March 1997. They have two elder and two younger half-siblings.

Aisha attended the Amman Baccalaureate School, and she received her Master’s Degree in Religion, Law, and Society from the University of Westminster. In June 2024, she announced her engagement to Kareem Al Mufti.

Sara also attended the Amman Baccalaureate School. She led the Jordanian delegation at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

Louise-Élisabeth of France & Henriette of France

Louise-Élisabeth of France & Henriette of France (public domain)

Louise-Élisabeth of France & Henriette of France (public domain)

Louise-Élisabeth of France & Henriette of France were the twin daughters of King Louis XV of France and Marie Leszczyńska. They were born on 14 August 1727 and were the couple’s first children. They would go on to have a total of eight siblings, of which three died in childhood.

Louise-Élisabeth was the firstborn and she was known at court as Madame Première. On 25 October 1739, she married the future Philip, Duke of Parma, and they had three children together. She died of smallpox on 6 December 1759, and she was buried beside Henriette in the Basilica of St Denis.

Henriette was the younger twin, and she was known as Madame Seconde. When her sister left to marry the future Duke of Parma, she became physically ill.1 Henriette took part in court life, but she never married. In February 1752, she fell ill shortly after going on a sleigh ride with her father. She died three days later, on 10 February 1752.

Adélaïde of Orléans & Françoise of Orléans

Adélaïde of Orléans & Françoise of Orléans (public domain)

Adélaïde of Orléans & Françoise of Orléans (public domain)Adélaïde and Françoise were the twin daughters of Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (known also as Philippe Égalité) and Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon. They were born on 23 August 1777. They had three surviving siblings. The two princesses came into the world “with their feet blackened, as though bruised, and very delicate.”2

Françoise was the elder twin, and she was known as Mademoiselle d’Orléans. She died sometime in 1782 of measles. Her mother, “who had remained constantly” with Françoise “night and day up to her last moments,” also fell ill but recovered. The Comtesse de Genlis wrote, “Nothing can express the sorrow felt by this child at the death of her sister.”3

Adélaïde was initially known as Mademoiselle de Chartres but she became known as Mademoiselle d’Orléans after Françoise’s death. Several marriages were considered for her, but in the end, she did not marry. She left France shortly before the French Revolution. Her father was guillotined. She eventually joined her mother in Spain. She returned to France after the fall of Napoleon. Her brother became Louis Philippe I, King of the French, in 1830, for which she had actively campaigned. She died on 31 December 1847.

Part two coming soon.

The post Princesses & Twins (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 2, 2025

Queen Zheng Mao of Chu – The Sensible Queen of Chu

Queen Zheng Mao of Chu (also known as Queen Zi Mao) was originally a Princess of the State of Zheng.[1] She was originally sent to be an Imperial Consort to King Cheng of Chu.[2] Because of her “steadfastness to principle”[3], King Cheng of Chu was deeply impressed with her and made her his queen.[4] Queen Zheng Mao of Chu has been known for her wisdom.[5] However, King Cheng of Chu did not listen to her.[6] His unwillingness to follow her advice led him to have disastrous consequences.[7] It caused his downfall and created political turmoil in Chu.[8]

Queen Zheng Mao of Chu was born in the seventh century B.C.E.[9] She lived during the Spring and Autumn era (which lasted from 771 to 453 B.C.E).[10] During this period, Chinese states were declaring their own independence from the ruling Zhou Dynasty to form their own dynasties.[11] Her origins are still disputed.[12] According to the Chinese historian Constance Cook, she was a woman from the Ying clan of the State of Zheng (modern-day Henan Province).[13] However, it is most likely that Queen Zheng Mao was a Princess of Zheng.[14] She was most likely from the ruling Ji clan of the State of Zheng.[15] She was sent to accompany a Princess from the Ying clan of the more powerful State of Qin.[16] The Princess of the Ying clan of Qin was supposed to be the Queen of King Cheng of Chu (who reigned from 671-626 B.C.E.).[17] Princess Zheng Mao was supposed to be an Imperial Consort of King Cheng of Chu.[18]

Once Princess Zheng Mao arrived in Chu, King Cheng of Chu looked down on the women’s quarters.[19] He noticed all the palace women looked up at him, except for Princess Zheng Mao.[20] This intrigued him, and he decided to test Princess Zheng Mao to make her look up at him.[21] He told her that he would make her his queen if she would look at him.[22] Princess Zheng Mao still refused to look up at him.[23] He then offered her 1,000 pieces of gold and to ennoble her father and brothers.[24] Princess Zheng Mao again refused.[25] She said that if she agreed to look up at him, she would be found “guilty of covetousness.”[26] King Cheng of Chu was delighted with her response.[27] He also praised her for her “steadfastness to principle.”[28] He made Princess Zheng Mao his queen.[29]

A year later, King Cheng of Chu contemplated making his son, Shangchen, the Crown Prince.[30] He consulted with his chief minister on whether he should make Shangchen the Crown Prince.[31] However, his chief minister told him not to make Shangchen the Crown Prince because he feared Shangchen was capable of ruthlessness.[32] King Cheng of Chu then asked for Queen Zheng Mao of Chu’s advice.[33] She agreed with his chief minister.[34] However, King Cheng of Chu refused their advice and made Shangchen the Crown Prince.[35] Crown Prince Shangchen eventually slandered King Cheng of Chu’s chief minister by blaming him for a military failure and had him executed.[36]

King Cheng of Chu gradually decided to replace Shangchen as the Crown Prince and make Prince Zhi (one of his younger sons by an imperial concubine) instead.[37] However, Queen Zheng Mao of Chu was against the replacement of Shangchen because she feared it would lead to disastrous consequences for Chu.[38] However, King Cheng of Chu refused to listen to her advice.[39] Instead, King Cheng of Chu suspected Queen Zheng Mao of jealousy because Prince Zhi was not her biological son.[40] Because King Cheng of Chu suspected her of “living without righteousness”[41], Queen Zheng Mao of Chu committed suicide.[42] Shortly after her suicide, Crown Prince Shangchen started a coup d’etat against his father.[43] This led to King Cheng of Chu committing suicide by hanging himself in 626 B.C.E.[44] Crown Prince Shangchen ascended to the Chu throne as King Mu.[45]

Queen Zheng Mao of Chu was blessed with political acumen.[46] She was intelligent and righteous.[47] However, her husband did not listen to her.[48] By refusing her advice, it had drastic consequences for both him and his kingdom.[49] If King Cheng of Chu had listened to Queen Zheng Mao of Chu’s advice, his ending would have been very different.[50] In Biographies of Eminent Women, Queen Zheng Mao of Chu is categorized under “Biographies of the Chaste and Righteous.”[51].

Sources:

Cook, C. A. (2015). “Zheng Mao, Wife of the King of Cheng of Chu”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 93-94.

Eno, R. (2010). 1.7. Spring and Autumn China (771-453). Indiana University, PDF.

Liu, X., Kinney, A. B. (2014). Exemplary Women of Early China: The Lienü Zhuan of Liu Xiang. United Kingdom: Columbia University Press.

[1] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[2] Cook, 2015

[3] Cook, 2015, p. 93

[4] Cook, 2015

[5] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[6] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[7] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[8] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[9] Cook, 2015

[10] Eno, 2010

[11] Eno, 2010

[12] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[13] Cook, 2015

[14] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[15] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[16] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[17] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[18] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[19] Cook, 2015

[20] Cook, 2015

[21] Cook, 2015

[22] Cook, 2015

[23] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[24] Cook, 2015

[25] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[26] Cook, 2015, p. 93

[27] Cook, 2015

[28] Cook, 2015, p. 93

[29] Cook, 2015

[30] Cook, 2015

[31] Cook, 2015

[32] Cook, 2015

[33] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[34] Cook, 2015

[35] Cook, 2015

[36] Cook, 2015

[37] Cook, 2015

[38] Cook, 2015

[39] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[40] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[41] Cook, 2015, p. 94

[42] Cook, 2015

[43] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[44] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[45] Liu and Kinney, 2014

[46] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[47] Liu and Kinney; Cook, 2015

[48] Cook, 2015

[49] Liu and Kinney; 2014; Cook, 2015

[50] Liu and Kinney, 2014; Cook, 2015

[51] Cook, 2015, p. 94

The post Queen Zheng Mao of Chu – The Sensible Queen of Chu appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 1, 2025

Book News Week 10

Book News week 10 – 3 March – 9 March 2025

Vagabond Princess: The Great Adventures of Gulbadan

Paperback – 4 March 2025 (US)

The Two Eleanors of Henry III: The Lives of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor de Montfort

Paperback – 6 March 2025 (US)

The post Book News Week 10 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 28, 2025

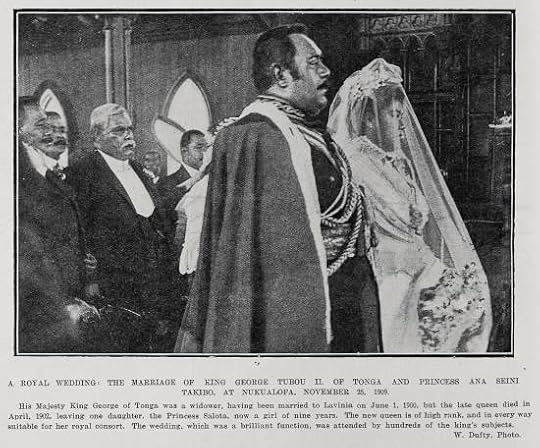

The Year of Queen Sālote Tupou III – ʻAnaseini Takipō, the unloved stepmother

Princess Sālote’s mother, Lavinia, died in 1902 when Sālote was just two years old. Her parents’ marriage had been quite controversial as King George had originally been meant to marry Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu, but he had chosen Lavinia instead. With Lavinia dead and in order to appease those who had been offended by his first marriage, he now chose to marry Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu’s half-sister, Princess ʻAnaseini Takipō. Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu herself had died in 1901 of tuberculosis.

Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu – Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18990630-02-03

Princess ʻOfakivavaʻu – Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-18990630-02-03ʻAnaseini Takipō was born on 1 March 1893 as the daughter of Tēvita Ula Afuhaʻamango, Noble of Vavaʻu, and Siosiana Tongovua Tae Manusā. She was just sixteen years old when she married Salote’s father. Sālote was reportedly “devastated” to learn he was to remarry.1 Sālote was nine years old at the time, and if her father and ʻAnaseini Takipō had a son, she would be displaced in the line of succession.

George and ʻAnaseini Takipō were married on 11 November 1909. Trying to outshine the King’s previous wedding, the bride’s family provided a wedding dress costing £100 and a trousseau worth £500. George spent £400 on the fakapapālangi wedding ceremony and breakfast.2 ʻAnaseini Takipō wore an empire gown trimmed with pearls and roses.3

In the tradition of Tonga, children from an earlier marriage were in danger of being killed. George claimed he was sending Sālote away for her education, but she was sent on the earliest possible steamer in December 1909, and she left without the customary companions. She was brought to Auckland and left with a family called Kronfeld.4 Despite the circumstances, ʻAnaseini Takipō wrote letters to her new stepdaughter.

(Public domain – Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19091208-0026-01)

(Public domain – Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19091208-0026-01)A son was expected, and ʻAnaseini Takipō fell pregnant in 1910. She gave birth to her first child, a daughter named ʻElisiva Fusipala Taukiʻonelua, on 20 March 1911. Sālote never met this half-sister as the infant tragically died just five months later on 11 August 1911. In December 1911, Sālote came home to Tonga to visit, and ʻAnaseini Takipō waited to greet her. She returned to Auckland shortly after her 12th birthday, and by then, ʻAnaseini Takipō was pregnant again. On 26 July 1912, she gave birth to a second daughter, Princess ʻElisiva Fusipala Taukiʻonetuku. Sālote received the news via telegram.

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19091209-04-05

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19091209-04-05The relationship between Sālote and ʻAnaseini Takipō was never warm, and during a visit in 1912, Sālote may have insulted her stepmother.5

In 1914, ʻAnaseini Takipō was one of the first recipients of the newly founded Tongan Order of the Crown, and she was appointed as Knight Grand Commander. The First World War had recently broken out and Tonga declared neutrality despite being a British Protectorate. When Tonga joined the United Kingdom in the war, the medals of German providence were put away.

From around 1915, Princess Sālote was back in Tonga, and the animosity towards her stepmother became more apparent. Sālote was annoyed at the Queen for her relaxed ways and her eating together with the servant girls on the veranda.6 She claimed that her father and ʻAnaseini Takipō were not well-suited and continued to “torment” her stepmother. The Queen’s family also insisted on treating her half-sister as the only royal princess. ʻAnaseini Takipō was from a higher female than Sālote’s mother, Lavinia. Sālote would later claim that the women of their family had bad blood.7

By 1917, it was clear that ʻAnaseini Takipō would have no more children. Without a son, Princess Sālote was first in the line of succession. In early 1917, her father became ill and was clearly in declining health. Around this time, a suitor for Sālote was found who met with the approval of the Privy Council, the public and the royal family. His name was Tungī Mailefihi. They were married on 19 September 1917. Her father looked well despite still being ill. ʻAnaseini Takipō wore a white silk dress and a light gold coronet.8 The Tongan ceremony followed two days later.

When King George Tupou II died on 5 April 1918, Sālote had just turned 18 years old, and she was six months pregnant. His immediate cause of death had been heart failure, although he had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. He was still only 43 years old. ʻAnaseini Takipō attended his funeral “heavily veiled.” 9 Tonga went into six months of official mourning. During this time, Sālote gave birth to her first child, a son named Tāufaʻāhau Tupou. In October, Queen Sālote had her coronation.

Disaster struck not much later. A ship had brought the deadly influenza virus to Tonga. The disease spread quickly, and the loss of life was immense. The royal family was not spared either. Queen Sālote’s husband became very ill, and Sālote was also sick but had no fever.

ʻAnaseini Takipō had been living with her daughter at Finefekai since the death of the King. She died of the disease on 25 November 1919, still only 25 years old. She was buried at Malaʻeʻaloa rather than the royal burial ground at Mala’ekula. Queen Sālote explained this by saying that ʻAnaseini Takipō had returned to her own family, and so it was the responsibility of her birth family to attend her burial. One can only wonder if there wasn’t a bit of animosity involved in that decision.

Queen Sālote took her half-sister into her care if only to take her away from the influence of her maternal family.

The post The Year of Queen Sālote Tupou III – ʻAnaseini Takipō, the unloved stepmother appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 27, 2025

Princess Lalla Khadija – The King’s daughter

Princess Lalla Khadija of Morocco was born on 28 February 2007 as the youngest child of King King Mohammed VI and Princess Lalla Salma of Morocco. On the occasion of her birth, her father gave out a pardon to 9,000 prisoners.1

Her name refers to the first wife of the Prophet Muhammad.

Embed from Getty ImagesShe has a brother, Crown Prince Moulay Hassan, who is four years older. As a woman, she is not in the line of succession to the Moroccan throne.

She is currently studying at the Royal College of Rabat, where she is reportedly an excellent student. It is said she enjoys playing instruments, singing, swimming, horse riding and travelling.

Embed from Getty ImagesDue to her age, she hasn’t made a lot of public appearances.

She accompanied her brother and their classmates to the COP22 in Marrakech in 2016. She opened the African Reptile Pavilion at the National Zoological Garden of Rabat in 2019. She was seen during Throne Day in 2023 and was seen alongside her family when French President Emmanuel Macron and First Lady Brigitte Macron made a state visit to Morocco.

The post Princess Lalla Khadija – The King’s daughter appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 25, 2025

Book Review: Early English Queens, 650–850: Speculum Reginae by Stefany Wragg

English Queens from the years 650-850 have been largely confined to the sidelines of history.

There were not only various kingdoms in what we now know as England, but written sources were also in short supply. Early English Queens, 650–850: Speculum Reginae by Stefany Wragg tries to piece together the lives of the almost 30 women who were Queen during this time.

While very interesting and well-written, there is often so little information available that it becomes frustrating. Nevertheless, their roles are thoroughly analysed and examined. Despite being aimed at a more scholarly audience, it is quite readable if you’re not a scholar.

Early English Queens, 650–850: Speculum Reginae by Stefany Wragg is available now in the UK and the US.

The post Book Review: Early English Queens, 650–850: Speculum Reginae by Stefany Wragg appeared first on History of Royal Women.