Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 149

May 5, 2021

Tsarina: A Novel by Ellen Alpsten Book Review

The origins of the future Catherine I of Russia are rather obscure. She was probably born as Marta Helena Skowrońska on 15 April 1684. Her parents died of the plague when she was still quite young, and she was raised by a pastor, in whose household she was probably a servant. She received little education and could not read or write. She was considered beautiful, and at the age of 17, she was married to a Swedish dragoon. When the city they lived in was captured by Russian forces, the pastor offered to work as a translator, and they were taken to Moscow. She later became part of the household of Prince Alexander Menshikov, who also happened to be the best friend of Peter the Great. Marta finally met Peter in 1703 when he was visiting Prince Alexander.

By 1704 she had become his mistress, and they had a son, also named Peter. They would have a total of twelve children, but only two daughters would survive to adulthood.

Ellen Alpsten brings Catherine to life in her debut novel, Tsarina, with graphic tales of poverty, abuse, war and eventually her life with Peter the Great. It’s brutal but enthralling, and you won’t want to put the book down.

I am normally not that into historical fiction, but perhaps it helps that we know so little about her origins, and thus a lot can be left to the imagination. I would highly recommend this book!

Tsarina: A Novel by Ellen Alpsten is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Tsarina: A Novel by Ellen Alpsten Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 3, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Reuniting in France

The abdicated King waited impatiently in Austria for Wallis’ divorce to become final, which it finally did on 3 May 1937. On 14 April, Edward wrote to Wallis, “This is just a line to say I love you more and more my own sweetheart and praying that the next eighteen days and nights won’t drag too interminably for WE. Poor WE – and there must be such store of happiness for us after all these months of hell.”1

In her memoirs, she wrote of being reunited with him the following day. “Finally, on the morning on May 3, there was a telephone call from George Allen in London. My divorce decree had now become absolute. I telephoned David in Austria. ‘Wallis,’ he said, ‘the Orient Express passes through Salzburg in the afternoon. I shall be at Candé in the morning.'[…] David arrived at lunch-time with his equerry, Dudley Forward. David was thin and drawn. I could hardly have expected him to look otherwise. Yet his gaiety bubbled as freely as before. He came up the steps at Candé two at a time. His first words were, ‘Darling, it’s been so long. I can hardly believe this you, and I am here.’ Later, we took a walk. It was wonderful to be together again. Before, we had been alone in the face of overwhelming trouble. Now we would meet it side by side.”2

Just a few days later, the coronation of Edward’s brother took place, on the same date that had been planned for his own coronation. They listened to the ceremony on the radio. Wallis later wrote, “When we were briefly alone afterwards, he remarked in substance only this: ‘You must have no regrets – I have none. This much I know: what I know of happiness is for ever associated with you.’ In these first days together at Candé, we began to plan for the future.”3

Wallis’ former husband Ernest watched the procession from a balcony at 49 Pall Mall and commented, “I couldn’t have taken it if it had been Wallis.”4

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Reuniting in France appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 2, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis and Ernest Simpson (Part two)

Something surely had changed. The Prince began visiting her home several times a week, and Ernest was surprisingly tolerant of the entire situation. He found ways to excuse himself as Wallis and the Prince talked until the small hours. Ernest soon realised that they were growing apart, and by 1935 Wallis wrote, “I had the feeling that more than business was now drawing him back to America. We were both going our separate ways; the core of our marriage had dissolved; only a shell remained – a façade to show the outer world.”1 Ernest had indeed had an affair during a trip to America – with their friend Mary Raffray. It is not clear if he told Wallis about it.

In March 1936, shortly after the Prince succeeded as King Edward VIII, Wallis took a short trip to Paris, and the two men in her life reportedly came together to settle the inevitable. Ernest and the King met at York House, and the King told Ernest that he intended to marry Wallis. Ernest then travelled to Wallis in Paris and informed her that an understanding had been reached. He confessed his feelings for Mary Raffray and that he had agreed to divorce Wallis as the King promised to take care of her. Wallis was outraged that the matter had been settled without her involvement; she had never intended to divorce Ernest. The King refused to accept anything other than marriage to Wallis, and her protests were ignored. He continued to shower her with gifts and bestowed a substantial amount of money on her from his private fortune. It wasn’t until June that Wallis agreed to divorce Ernest. The King wanted it to happen as soon as possible as he wanted to marry her before his coronation in May. If she filed for divorce now, the case would be heard in the autumn and settled by April, as per the six-month waiting period.

The only circumstance in which divorce was permitted was where the petitioner could show that the respondent had grievously damaged the marriage through improper conduct. So, Ernest duly booked himself into a hotel to commit the public charade of adultery, and after the divorce proceedings were well underway, he began living with Mary. However, Wallis was still dragging her heels and tried to break up with the King, writing, “I am sure you and I would only create disaster together.”2 She later told author Gore Vidal, “I never wanted to get married. This was all his idea. They act as if I were some sort of idiot, not knowing the rules about who can be Queen and who can’t. But he insisted.”3

On the advice of her solicitor, the divorce would be heard outside of London, and Ipswich was selected. Wallis took up temporary residence there, as was required, and she lived in a cottage called Beech House. Before leaving, Wallis and the King travelled to Balmoral, and he even dispatched his brother, The Duke of York, in his place to an engagement, claiming to be still in mourning. When the Duke and Duchess of York learned he had picked up Wallis from the train station, they were quite angry.

On 27 October, the divorce case was heard in Ipswich, and the six-month waiting period would be set to end on 27 April. The King’s coronation had been scheduled for 12 May, leaving just enough time to marry Wallis and have her by his side at the coronation. Wallis was so nervous the night before the divorce case that she could not sleep, and she spent hours pacing. Ernest was not present for the court case and was represented by his lawyer, North Lewis. Wallis took the stand and was questioned by Justice Hawke before two employees of the hotel where Ernest had stayed were questioned. Justice Hawke granted the decree nisi, and then it was just a matter of waiting.

As the waiting period and the abdication played out during these few months, Wallis eventually fled to France. Yet, she continued to write to Ernest, and he wrote to her, “My thoughts have been with you throughout your ordeal, and you may rest assured that no one has felt more deeply for you than I have.”4 Ernest too was facing a great deal of criticism, and Wallis wrote to him, “I am really so sorry about all the unjust criticism you have had.”5

After the divorce became final, Wallis wrote to Ernest, “I have taken back the name of Warfield as I really felt that I had done the name Simpson enough harm. Now the target can be Warfield as I don’t expect the world to let up on its cruelty to me for some time… It’s impossible to have anyone here & also impossible to move – literally surrounded by press and photographers etc… The publicity has practically killed me.”6

Embed from Getty ImagesErnest remarried twice after his divorce from Wallis, but they continued to write (infrequently) to each other. His third wife was Mary Raffray, and they were married until her death in 1941. They had a son together, who was born in 1939. His fourth and final marriage was to Avril Leveson-Gower, which lasted until Ernest’s death in 1958. Wallis sent white chrysanthemums to his funeral with a card that said, “From the Duchess of Windsor.”

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis and Ernest Simpson (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis and Ernest Simpson (Part one)

On 3 May 1937, Wallis was granted her decree absolute, and she was now officially divorced from Ernest Simpson – they had been married for almost nine years. What had Wallis’ life been like as Mrs Simpson?

Wallis and Ernest Aldrich Simpson had met sometime in 1926 as she waited out her divorce from Earl Winfield Spencer Jr. through friends of hers, Mary (née Kirk) and her husband, Jacques Raffray. Ernest was then still married to Dorothea Webb Dechert, with whom he had a daughter named Audrey (born in 1924). Ernest’s father was British, but Ernest himself had been born in New York, and he had graduated from Harvard. During the last year of the First World War, Ernest had travelled to England and joined the Coldstream Guards as a second lieutenant and he eventually became a British citizen. Wallis and Ernest grew closer over time, with Dorothea bitterly commenting, “From the moment I met her, I never liked her at all… she moved in and helped herself to my house and my clothes and finally, to everything.”1

Embed from Getty ImagesErnest and his wife decided to divorce, and he asked Wallis to marry him once they were both free. Wallis wrote in her memoirs, “I had come to admire him for his high qualities of mind, stability of character, and cultivation. But I was not altogether sure that my Southern temperament was exactly suited to such a man. Still, for the first time in a long while, I felt myself falling unmistakenly in love; and when I left Pennsylvania Station to return to Warrenton, I carried an armful of books that Ernest had chosen for me.”2

Wallis’ divorce from her first husband became final on 10 December 1927, and once more, Ernest asked her to marry him. Wallis wrote to her mother, “I am very fond of him, and he is kind, which will be a contrast… I can’t go wandering on the rest of my life, and I really feel tired of fighting the world all alone and with no money. Also, 32 doesn’t seem so young when you see all the really fresh youthful face one has to compete against.”3 The exact date of Ernest’s divorce is unclear, but he and Wallis were married on 21 July 1928 at the Chelsea Registry Office in London. She wore a bright yellow dress with a blue coat. She later recalled that “the setting was more appropriate for a trial than for the culmination of a romance; and an uninvited sudden surge of memory took me back to Christ Church at Baltimore, and the odour of lilies and the bridesmaids in lilac and the organ playing softly.”4

They honeymooned in Paris for a week before temporarily settling in a small hotel while Ernest returned to work, and Wallis began the search for a house with the help of Ernest’s sister Maud. She finally leased 12 Upper Berkeley Street for a year. Their household included a butler, a cook, a maid, a parlour maid, a housemaid and a chauffeur. Wallis knew barely anyone in London, but she was determined to fit in. She began reading the newspapers and the Court Circular. She played the tourist and was often invited by Maud to parties and luncheons. In October 1929, Wallis rushed to the United States after her mother lapsed into a coma. She died on 2 November 1929 with Wallis and her sister Bessie by her side. Aunt Bessie would become Wallis’ confidant.

By then, the lease on the house was up and once again, Wallis had to go househunting. She found a flat on the first floor at 5 Bryanston Court, on George Street, with three bedrooms and four servants’ rooms. While the previous house had come with furnishings, the new flat had to be decorated by Wallis herself – not that she minded. From here, Wallis was able to grow her and Ernest’s social circle, and they were eventually able to include the 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven and his wife – who were closely related to the Royal Family – and Benjamin and Consuelo Thaw. Consuelo was one of the three Morgan sisters, and it was her sister Thelma, Viscountess Furness, who would introduce Wallis to the Prince of Wales.

In early January 1931, Consuelo invited Wallis to the Furness home at Melton Mowbray for a week away. The Prince of Wales and Thelma would both be there, but Consuelo couldn’t make it. Convention demanded that one married couple should act as chaperones, and Consuelo asked if the Simpsons would be able to help out. Wallis nervously accepted the invitation as it could prove to be an excellent step up the social ladder for both her and Ernest. Wallis spent the entire Friday on her hair and nails and battling an inconvenient cold. On 10 January 1931, Wallis met the man who would become her third husband. Wallis later wrote of the weekend, “I decided that the Prince was truly one of the most attractive personalities I had ever met. He had a rare capacity for evoking an atmosphere of warmth and mutual interest, and yet it was hardly bonhomie. […] I had been fascinated by the odd and indefinable melancholy that seemed to haunt the Prince of Wales’s countenance; his quick smile momentarily illuminated but never quite dispelled this look of sadness.”5 They would not meet again until several months later.

Shortly after their second meeting, Wallis was presented at court. As she was a divorcee, Wallis could only be presented if she was the injured party, and she had to send her divorce papers to the Lord Chamberlain, hoping that she would be accepted – which she was.

On 10 June 1931, Wallis borrowed a dress, train, feathers and a fan from Thelma’s sister Consuelo and bought herself a large aquamarine cross necklace and white three-quarter-length gloves. Wallis dutifully curtsied for King George V and Queen Mary. The Prince of Wales was also present, and she overheard the Prince muttering something about the light making all the women look ghastly. Afterwards, Wallis and Ernest were invited over to Thelma’s house, where the Prince was also present. He made an admiring remark about her gown to which Wallis retorted, “But Sir, I understood that you thought we all looked ghastly.” He was quite amused rather than offended and offered to drive Wallis and Ernest home that night.6

In early 1932, Wallis and Ernest entertained the Prince in their flat at Bryanston Court for the first time. He stayed until 4 a.m. and even asked for one of her recipes. At the end of January, they were also invited to spend the weekend with him at Fort Belvedere. Although she was slowly rising in the ranks, her and Ernest’s finances were suffering, and she had barely seen her husband in 1932 as he travelled a lot for business. More weekends at the Fort followed.

She began the year 1934 celebrating with the Prince until 5 a.m, following by dinner later that day, also with the Prince. Then came the trip that changed everything – Thelma was leaving for a trip to the United States, and according to Wallis, she asked, “I’m afraid the Prince is going to be lonely. Wallis, won’t you look after him?”7 According to Thelma’s memoirs, it was Wallis who initiated the topic with the words, “Oh, Thelma, the little man is going to be so lonely.” To which Thelma replied, “Well, dear, you look after him for me while I’m away.”8 Thelma sailed on 25 January 1934 – paving the way for Wallis to rise from friend to favourite.

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis and Ernest Simpson (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 29, 2021

Julia, Princess of Battenberg and the origins of the Mountbatten name

The name Mountbatten was the anglicised name that the Battenberg family in England took during the First World War. But who were the Battenbergs to begin with? The name was created for Julia von Hauke, who became Countess and then Princess of Battenberg. Julia was the great-grandmother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

Julia von Hauke, born in 1825, was the daughter of a Polish general, Count John Moritz Hauke, and Sophie Lafontaine. Her father was killed during the Polish November uprising of 1830, and her mother died shortly thereafter. Julia was then made a ward of the Russian Emperor who controlled Poland at the time.

Julia became a lady-in-waiting to Marie of Hesse, the wife of the future Emperor Alexander II of Russia. As a result, she met Marie’s brother Alexander of Hesse, who had accompanied Marie to Russia at the time of her marriage and had remained as a member of the Russian army. Alexander of Hesse and Julia fell in love, but the Emperor forbade their marriage as he had plans for Alexander to marry his niece. In 1851, Julia and Alexander eloped – leaving Russia behind. They married in Breslau, and their first child – named Marie – was born in 1852. The Emperor struck Alexander from his position in the army, but Alexander’s brother, the Grand Duke of Hesse, was more sympathetic. He allowed the couple to settle in Hesse, but the marriage was considered morganatic. Alexander and his descendants were removed from the line of succession to the. The Grand Duke did, however, grant Julia the title of “Countess of Battenberg”, and their children were styled as “Illustrious Highnesses.” The name Battenberg was taken from a small ruined castle in the north of Hesse. Their daughter Marie remembered visiting Battenberg only once as a child.

Alexander and Julia with their daughter Marie (public domain)

Alexander and Julia with their daughter Marie (public domain)The young couple must have had a certain charm because they did manage to bring many of their relatives around. A few years after their marriage, Alexander’s brother raised Julia’s position to that of “Princess of Battenberg” and with the style of “Serene Highness.” The children were then styled Princes and Princesses of Battenberg. It certainly helped that back in Russia, Marie and Alexander were now Emperor and Empress, and they remained friendly with the couple. When they would visit Marie’s family in Hesse, they would often be entertained by Alexander and Julia, and it was to their home that the diplomats would come to meet with the Emperor.

Alexander joined the Austrian army, and initially, he and Julia moved around depending on his postings. After the Austrian defeat by Prussia, he and Julia lived in Heiligenberg Castle in Darmstadt. They had five children: Marie, the only daughter; Louis, who married Victoria of Hesse – a favourite granddaughter of Queen Victoria; Alexander, who was briefly King of Bulgaria; Henry, who married Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter Beatrice; and Franz Joseph, who married Princess Anna, the daughter of the King of Montenegro.

(public domain)

(public domain)Queen Victoria seems to have had no issue with her relatives marrying into the morganatic Battenberg family. Her daughter Alice had married Alexander’s nephew, the future Grand Duke of Hesse, in 1862, and she seems to have been fond of the whole family. In her letters to her granddaughter Victoria, the wife of Julia’s son Louis, she would often refer to Julia as “your dear mother-in-law.” When Julia died in 1895, Queen Victoria wrote: “The dreadful news of your mother-in-law distresses me so much. She was much beloved at Jugenheim and Darmstadt and was so charitable and kind to the poor. You will, I am sure, try to make them feel that you will follow her example.“

At times, however, the issue of Julia’s humble beginnings did raise issues for her children. Prince Alexander had hoped to marry Princess Viktoria of Prussia, but the word from Germany was that “no Hohenzollern would marry a Battenberg.” And when Prince Henry and Princess Beatrice’s daughter Victoria Eugenie became engaged to King Alfonso XIII of Spain, there was much grumbling in Spain about her origins.

Two of Julia and Alexander’s children ended up in England. Prince Louis had joined the Royal Navy at the age of 14 and rose to become First Sea Lord. He was forced to resign in 1914 because of his German origins. Prince Henry had had to agree to live with Queen Victoria in order to get approval to marry Beatrice. After the First World War, when King George V was removing German names from his relatives, the Battenbergs became the Mountbattens. The princely title was dropped, and Louis was made Marquess of Milford Haven, and Henry’s son was made Marquess of Carisbrooke.

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, was a grandchild of Prince Louis of Battenberg and Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine. He took the Mountbatten name as his surname at the time of his marriage to Princess Elizabeth. Other descendants of Julia include Queen Louise of Sweden (1889-1965), the Spanish royal family, and Earl Mountbatten of Burma (1900-1979).

The post appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Zulu Queen Mantfombi Dlamini dies a month after becoming regent

Zulu Queen Mantfombi Dlamini has died at the age of 65, just one month after becoming regent following the death of her husband, King Goodwill Zwelithini.

“It is with the deepest shock and distress that the Royal Family announces the unexpected passing of Her Majesty Queen Shiyiwe Mantfombi Dlamini Zulu, Regent of the Zulu Nation,” Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, the prime minister, said in a statement. He said he wanted to assure people that there would be “no leadership vacuum in the Zulu Nation.” He also dismissed rumours that the Queen had been poisoned.

Queen Mantfombi had been admitted to hospital a week ago for an unspecified illness, according to South African media. “When she left, she was ill, and rumours were that she was poisoned,” Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi told national broadcaster SABC. He added that she had been ill for some time.

Queen Mantfombi had been appointed to the role of regent on 24 March, after her 72-year-old husband, King Goodwill Zwethilini, died in hospital from diabetes-related complications.

The late Queen was the daughter of King Sobhuza and sister to King Mswati III of Eswatini, which gave her a higher status among King Goodwill Zwelithini’s five wives. As the “great” wife, one of her sons would be the most obvious successor as King.

The post Zulu Queen Mantfombi Dlamini dies a month after becoming regent appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 28, 2021

Royal Wedding Recollections – Catherine Middleton & Prince William

On 29 April 2011, Catherine Middleton married her long-term boyfriend Prince William, who was created Duke of Cambridge, Earl of Strathearn, and Baron Carrickfergus upon marriage1, so that Catherine would become known as Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cambridge.2 Although she is not entitled to be called “Princess Catherine”, she does have the status of a Princess as was confirmed by the palace upon the marriage of the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King George VI and Queen Elizabeth). “In accordance with the settled general rule that a wife takes the status of her husband Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon on her marriage has become Her Royal Highness the Duchess of York with the status of a Princess.“3

Embed from Getty ImagesThe couple became engaged in October 2010 while on holiday in Kenya, and the engagement was announced on 16 November 2010. Prince William gave Catherine his mother’s blue sapphire engagement ring, and the wedding was set for 29 April 2011 at Westminster Abbey.

Catherine wore a satin and lace wedding dress by Sarah Burton by Alexander McQueen. She wore the Cartier Halo tiara loaned to her by The Queen. Her wedding bouquet included myrtle, Lily of the Valley, Sweet William and hyacinth. Her diamond earrings were a gift from her parents. Prince William wore the uniform of the Irish Guards mounted officer.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesPrince Harry was Prince William’s best man, while Catherine’s sister Pippa was her maid of honour. The bridesmaids and pageboys included Lady Louise Windsor, Margarita Armstrong-Jones, Grace van Cutsem, Eliza Lopes, William Lowther-Pinkerton, and Tom Pettifer. Catherine’s younger brother James gave a reading at the service.

The Dean of Westminster officiated the service, while the Archbishop of Canterbury acted as the celebrant, and the Bishop of London preached a sermon. Guests came from both sides of the family, and there were also plenty of royal guests even though it was not a state occasion, as William is “only” second in line to the throne. Royal guests included the King of Bhutan, the Grand Duke and Grand Duchess of Luxembourg and the Prince of Monaco with his fiancee Charlene.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe service began at 11.00 A.M. and lasted for an hour and fifteen minutes. They left Westminster Abbey in the 1902 State Landau, and just a short while later, they appeared on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to watch a flypast and, of course, the obligatory kiss. This was followed by a lunchtime reception, and later in the evening, there was a private dinner.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesTen years on, the couple have three children: Prince George (born 2013), Princess Charlotte (born 2015) and Prince Louis (born 2018).

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post Royal Wedding Recollections – Catherine Middleton & Prince William appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The funeral of the Duchess

From 1980, Wallis spent most of her days alone in a wheelchair. She was taken care of by nurses, who bathed her and put her hair in a bun. She often had to be spoon-fed, and periods of lucidity came and went. Eventually, the Countess of Romanones was allowed to visit her, though another friend noted that she believed this was done to placate the other friends. By then, Wallis’ hair had turned white, and she did not recognise the Countess. When the Countess visited again several months later, Wallis had gone completely blind. A friend named Janine Metz never gave up on calling and finally won permission to see Wallis. She said, “She was like a little bird, all shrivelled up. I came up very close to the bed, bent down and kissed her, she seemed to have no idea who I was, or even that I was in the room.” She whispered to Wallis, “I am Janine. I am here with you.”1 She pressed Wallis’ hand, and she pressed back – the only way she could still communicate. Janine would be one of the last of her friends to see Wallis.

By the beginning of 1984, Wallis was completely paralyzed. She was being fed with an intravenous drip, and the doctor visited her regularly. Nurses changed her drip, washed her body and turned her to prevent bedsores.

The Duchess of Windsor died on 24 April 1986 of heart failure following pneumonia – she was 89 years old. Reverend Jim Leo told the press, “Death came round the corner as a very gentle friend, and she was content, she was happy.”2 Her body was washed and dressed in a simple black dress with a jewelled belt before being placed in an oak coffin. No autopsy was performed on the body. On 27 April, the Lord Chamberlain – on Queen Elizabeth II’s instructions – flew to Paris to collect the Duchess’ body. That same day, they landed at RAF Benson, where Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester, waited to escort the body to Windsor. Eight members of the Royal Air Forced place the coffin into the waiting hearse, and a small motorcade escorted the procession to Windsor.

At St. George’s Chapel, eight members of the Welsh Guards carried her coffin inside to the Albert Memorial Chapel. Her funeral took place on 29 April at St. George’s Chapel at 3.30 P.M. Around 175 people were invited to attend the funeral, and during the service, her coffin rested on a catafalque before the high altar. On top of her coffin was a wreath from The Queen consisting of yellow and white madonna lilies. Sixteen members of the royal family attended the funeral, including The Queen, The Duke of Edinburgh, The Prince and Princess of Wales, Princess Anne and Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesThe service began with “I am the Resurrection and the Life”, which is a tradition for royal funerals. Then came psalm 90, a blessing and a prayer read by the Dean of Windsor. Several hymns and prayers followed before the Archbishop of Canterbury pronounced a final blessing and prayer. With the sounds of Enigma Variations, the Duchess’ coffin was carried out of the chapel. Not once was her name mentioned during the 28-minute long funeral.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe coffin was put back into a hearse and driven to the Frogmore burial ground, where she was laid to rest beside her husband. Reverend Jim Leo conducted a simple service at the graveside as the members of the Royal Family looked on.

Grave of Duchess of Windsor

Grave of Duchess of Windsorcc-by-sa/2.0 – © John Wieneman – geograph.org.uk/p/1886848

The Duchess of Marlborough commented, “I went to look at the flowers… It was tragic. They were all from dressmakers, jewellers, Dior, Van Cleef, Alexandre. Those people were her life.”3

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The funeral of the Duchess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 27, 2021

Cecilie of Greece and Denmark – A tragic destiny (Part two)

On 9 October 1937, Cecilie’s father-in-law died at the age of 68. On 12 October, Cecilie was joined by both her mother and grandmother for the funeral. There was a strong Nazi presence at the funeral, and both Cecilie and her husband had joined the Nazi party on 1 May 1937 (with party numbers 3766313 and 3766312, respectively). Cecilie’s husband now succeeded as Head of the House, but more tragedy was to come.

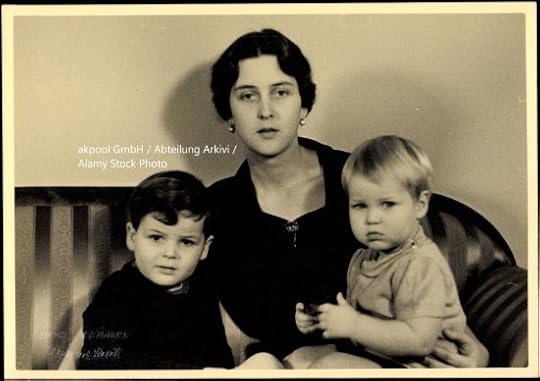

akpool GmbH / Abteilung Arkivi / Alamy Stock Photo

akpool GmbH / Abteilung Arkivi / Alamy Stock PhotoCecilie’s brother-in-law Louis was due to be married to Margaret Geddes in London, but the wedding was postponed to 20 November because of Ernest Louis’ death. Cecilie wrote to her uncle Lord Louis Mountbatten (later Earl Mountbatten of Burma) on 12 November, thanking him for putting up so many of the family. She added, “I hope we won’t be in the way.”1

On 16 November 1937, Cecilie, George Donatus, their sons Ludwig and Alexander, her mother-in-law Eleonore with her lady-in-waiting (sometimes also referred to as nanny to the boys) Lina Hahn and two friends of the family, Joachim Riedesel zu Eisenbach and Arthur Martens, boarded a flight to London. The plane was also scheduled to land in Brussels. The three-person crew consisted of Antoine Lambotte (pilot), Maurice Courtois (wireless operator) and Yvan Lansmans (mechanic). The passengers sat in leather seats that lined the sides of the plane, and they wore earplugs to protect them from the noise of the three engines but also forced them to shout if they wanted to share something. There wouldn’t be much to see from the windows as it was quite a foggy day.

The thick fog prevented the plane from landing in Brussels but just above Ghent, the wireless operator handed the pilot a note stating that he would have to land at Stene by Ostend to pick up two passengers. Brussels had assured the operator that it would be safe to land there as the visibility near the coast was a lot better. Above Bruges, the pilot requested an updated weather report from Stene, and they duly reported that the fog was coming in quickly there too. The pilot requested the guidelines for landing from his company, but they left the decision on whether or not to land up to him. He decided to go ahead with the landing and requested flares to be lit so that he could localise the airport.

Around 2.30 P.M., the search for the airport began. Three flares were planted, but apparently, only the first was on time and visible, the second did not go off, and the third was lit too late. This meant that the aeroplane flew over the airport at a relatively low altitude. The pilot turned and began to follow the railways back to the airport. The fog became worse and worse, which was also being signalled to the plane. The plane then hit the 50-metre high chimney of a brick factory with its right-wing, which was torn off and ended up in one of the warehouses. The rest of the plane ended up upside down in two parts in the middle of the brick factory – which was being operated at full power. It immediately burst into flames. The time was now 2.47 P.M.

Smith Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Smith Archive / Alamy Stock PhotoA witness later reported, “Several people from the factory ran towards the plane. They could hear screams, but it was impossible to help as the plane was one big fireball. So they saw those people being burned alive.” The passengers never had a chance to escape. When the fire died down, the cabin was in pieces, and the bodies of the passengers were clearly visible “in their grotesque positions” in charred seats. Newspapers also reported the discovery of the head of an infant, and Cecilie had been pregnant at the time of the crash. The newspaper Midi-Journal said a Belgian inquiry into the disaster indicated that the pilot attempted to land because Cecilie had gone into labour.2 However, it does seem strange that if there was any distress or emergency on board that this was not signalled to the ground. Therefore, it seems unlikely that this would be the cause of the crash, and the pilot was told to pick up passengers, so it was not like the plane diverted for an emergency. In the end, the fog was blamed for the accident, and as there was no malfunction of the aeroplane, it was classified as a “controlled flight into terrain.” Cecilie’s young daughter Johanna had remained at home due to her age and was now orphaned.

Cecilie’s brother-in-law Louis had been waiting for the arrival of the plane at Croydon when he was informed of the horrific events. His wedding to Margaret was moved to the following day with the guests dressed in mourning in St. Peter’s Church in Eaton Square. Lord Louis Mountbatten was the best man, and Margaret wore a black coat and a skirt. The newlyweds travelled to Ostend to collect the bodies and to bring them back to Darmstadt. That same morning, the bodies were removed from the aeroplane and put into caskets. Louis and Margaret arrived that evening on the ferry. The following day, the caskets were loaded onto a train and were taken to Darmstadt.3

Embed from Getty Images Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe funeral took place on 23 November at Rosenhöhe. Her mother, Alice, came from Berlin with her sister Sophie while her father, Andrew, came from London with her brother Philip. The funeral would be the first time her parents saw each other in six years. Her father later wrote, “I’m keeping fit up to a point, but I cannot say that time has had any healing effect – it was a very hard blow, and the weight of it becomes heavier as time passes.”4 For Alice, her daughter’s death was a turning point for her mental health. Theodora wrote, “The first curative shock to her was brought about by the plane-crash causing the death of her third daughter, her husband and children. Contrary to what was expected, it apparently tore her out of everything.”5

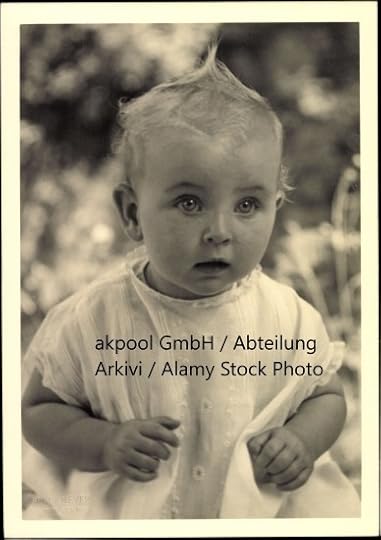

Princess Johanna – akpool GmbH / Abteilung Arkivi / Alamy Stock Photo

Princess Johanna – akpool GmbH / Abteilung Arkivi / Alamy Stock PhotoJohanna was adopted by her aunt and uncle, but tragically, the young Princess would die of meningitis on 14 June 1939. She, too, was buried at Rosenhöhe.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe post Cecilie of Greece and Denmark – A tragic destiny (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Inverness Castle to transform into visitor attraction

Inverness Castle is set to transform into a visitor attraction. The property was used as a sheriff’s court until the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service moved to a new building last year.

The current castle dates from 1836, and its transformation will include new exhibition space, cafes and a roof terrace – which could take up to five years to complete.

Mary, Queen of Scots, is linked to an earlier castle on the site. In 1562, she visited Inverness Castle – or rather she tried to. On 9 September, the gates of the castle were closed to her by Alexander Gordon on the order of the 4th Earl of Huntly. Subsequently, Mary’s supported besieged the castle for three days until it finally fell.

Alexander Gordon was hanged for treason with his head being displayed on the castle. Mary herself stayed at Inverness from 11 until 14 September before moving on to Spynie Palace. “I never saw the Queen merrier – never dismayed; nor never thought I that stomach to be in her that I find. She repented nothing but (when the Lords and others at Inverness came in the morning from the watch) that she was not a man, to know what life it was to lie all night in the fields, or to walk upon the causeway with a jack and a knapsack, a Glowgow buckler, and a broadsword.”1

The post Inverness Castle to transform into visitor attraction appeared first on History of Royal Women.