Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 146

June 4, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The funeral of the Duke of Windsor

The day after the Queen’s visit, the Duke seemed to improve a little, but on 25 May, he was unable to leave his bed. The following day, Wallis called their American physician Dr Arthur Antonucci to come to Paris to see the Duke. He dropped everything and was in Paris late that afternoon. After examining the Duke and conferring with Dr Thin and nurse Shanley, he told Wallis that there was nothing he could do. From then on, Wallis barely left the room.

Late Saturday night, the Duke told Wallis to get some rest. He said, “Darling, go to bed and rest. Oonagh (nurse Shanley) will look after me.”1 Just a few hours later, around 2.20 a.m., the Duke of Windsor died in his sleep. His nurse went to wake up Wallis, who kissed his forehead and cupped his face while saying, “My David, my David… You look so lovely.”2 The news was released by Buckingham Palace, and the text of a telegram sent by the Queen to Wallis was also released. “I know that my people will always remember him with gratitude and great affection and that his services to them in peace, and he will never be forgotten. I am so glad that I was able to see him in Paris ten days ago.”3

During the Duke’s visit to a London clinic in 1965, he had asked his niece if it would be possible for him and Wallis to be buried at Frogmore, and he had asked for their funeral services to take place in St. George’s Chapel. He had already purchased a burial plot in the Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore several years earlier as he had been unsure if he would be allowed to return to England – even in death. The Queen agreed to these requests ten days later as the publicity of a former King being buried in the United States would be unwelcome.

And so on 31 May, the Duke’s body was brought to England for burial and for the first time, Wallis was invited to stay at Buckingham Palace. She did not go at the same time as the Duke’s body as she felt absolutely devastated and remained secluded in Paris.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesShe followed on 2 June on an aeroplane from the Queen’s flight. She was welcomed by Lord Mountbatten, who helped her down the ladder.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe following day, the Court Circular finally recognised her existence as it mentioned her arrival in the country. Wallis would spend four days at Buckingham Palace, and she was received by the Queen in her private sitting-room. Wallis later recalled, “They were polite to me, polite and kind, especially the Queen. Royalty is always polite and kind. But they were cold. David always said they were cold.”4 A courtier recalled, “The Queen didn’t want to have much to do with Wallis. Dinner was given in the Chinese Room – with anybody else, it would have been in the Queen’s own dining room. She preferred to go down to where Wallis was set up. It was okay – everybody behaved decently. Charles was there, and helpful. But there was certainly no outpouring of love between the Queen and the Duchess of Windsor and vice versa.”5

Embed from Getty ImagesWallis was determined to remain dignified throughout the visit and told the Countess of Romanones, “In all the time I was there, no one in the family offered me any real sympathy whatsoever. They were going to continue to hate me no matter what I did, but at least I wasn’t going to let them see David’s wife without every shred of dignity I could muster.”6 On 3 June, Trooping the Colour went ahead as usual as the Queen refused to cancel it. Instead, she wore a black armband, and a piper’s lament was played. The Duchess of Windsor was caught by a photographer looking down on the event.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesAfterwards, the Queen went to Wallis to inform her that the family would be going to Windsor Castle and that she could join them if she wished. Wallis decided against going and remained behind alone at Buckingham Palace. That evening, Wallis visited St George’s Chapel, where the Duke lay in state. That day would have been their 35th wedding anniversary.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesOn 5 June, Wallis left Buckingham Palace for the funeral of her husband. She joined the other members of the royal family in St George’s Chapel and recalled how the Queen Mother was dressed. “I really must copy that outfit. It looked as if she had just opened some old trunk and pulled out a few rags, and draped them on herself. And that eternal bag hanging on her arm… She wore a black hat with the brim rolled up, just plopped on her head, and a white plastic arrow sticking up through it. I thought how David would have laughed.”7

Embed from Getty ImagesThe Duke’s coffin was carried down the nave and into the choir, followed by several male members of the royal family. It was then placed onto the catafalque. Wallis was often overwhelmed during the one-hour service, and the Queen helped her find the place in the order of service.

Embed from Getty ImagesAfterwards, she joined them in the private apartments for the after-funeral reception. Lord Mountbatten took Wallis to a sofa where she could rest and where she was surprisingly joined by the Queen Mother, who said to her, “I know how you feel. I’ve been through it myself.”8 The actual burial took place immediately after the reception, and Wallis wanted to return to Paris as soon as possible. She was not accompanied to the airport by a member of the royal family. Later that day, she walked back into the home they had shared for so long – alone.

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The funeral of the Duke of Windsor appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 3, 2021

Eleanor of Portugal – The first Habsburg Empress

Eleanor of Portugal was born on 18 September 1434 in Torres Vedras as the sixth child and third (but eldest surviving) daughter of King Edward of Portugal and Eleanor of Aragon. Het baptism was performed in the Cathedral of Lisbon by Archbishop Pedro de Noronha. Her parents entrusted her into the care of Guiomar de Castro, Countess of Atouguia. Three more siblings would follow, of whom two survived to adulthood. Her elder brother became Afonso V, King of Portugal.

Eleanor was almost four years old when she lost her father, and the custody of her elder brother was taken from her mother and transferred to her uncle Peter, Duke of Coimbra. This deeply affected her mother, who took her daughters to the castle of Almeirim. Her mother continued her attempts to regain the regency and left the then six-year-old Eleanor at Almeirim, who was ill. They would never see each other again. Peter hurried towards Almeirim to take custody of the young Eleanor. Her mother was eventually exiled, and she died on 19 February 1445. Guiomar de Castro continued to care for the young Eleanor, and she grew up with her two sisters Catherine and Joan, in the Royal Palace in Lisbon. Unfortunately, very little is known about her childhood.

Eleanor was barely 13 years old when Frederick, King of the Romans, who was nearly 20 years her senior, came looking for a wife. His ambassadors returned to Vienna with a portrait of Eleanor, which he liked. However, unrest in Portugal delayed wedding negotiations, and in May 1449, her uncle Peter was killed during the Battle of Alfarrobeira. Peace had barely been restored when Frederick renewed his interest in Eleanor in early 1450. This time, his letter was directly delivered to her brother Afonso V, now 18 years old. However, he now had competition in the form of Louis, Dauphin of France (the future King Louis XI of France), who had lost his first wife Margaret Stewart in 1445.

(public domain)

(public domain)Eleanor, however, was adamant that she would not marry the Dauphin and much preferred Frederick. Afonso approved the marriage to Frederick. The treaty was concluded on 10 December 1450, and Eleanor began German lessons. She boarded the ship that would take her to Rome on 25 October 1451, but her departure was delayed until 12 November due to the weather. Her brothers Afonso and Ferdinand followed her ship a few miles into the open sea. On 25 November, she arrived at Puerto de Ceuta, where she went to church and rested for a few days. After her departure, she was nearly lost at sea during a violent storm. She finally arrived in Italy but was not at the correct port. Eleanor was thoroughly exhausted, and the ships were haunted by more storms, and a messenger was sent to Frederick who told her to go overland to Pisa, where the waiting welcoming committee would meet her. The Bishop of Sienna then escorted Eleanor to Sienna, where she finally met her future husband.

Frederick was delighted by his new bride, and he hugged and kissed her. A marble column still marks the place of their first meeting. After four days, Frederick and Eleanor travelled to Rome, where they finally arrived on 8 March. On 16 March 1452, Eleanor and Frederick were married at St. Peter’s Basilica. Eleanor wore a red velvet gown with a white belt and a wrap of dark brocade. The wedding ceremony was performed by Pope Nicholas V and he put the wedding rings on their fingers himself. The following Sunday, 19 March, the newlyweds were crowned Holy Roman Emperor and Empress. Per tradition, Eleanor wore her hair down and had a golden circlet on her head. She was crowned with the crown that had previously been worn by Barbara of Cilli, her predecessor as Holy Roman Empress. Frederick would be the first Emperor from the House of Habsburg.

After all this splendour, the new Emperor and Empress travelled to Naples, where Eleanor’s uncle King Alfonso V of Aragon, Sicily and Naples reigned. He received his niece warmly on 2 April and although the festivities were all brilliant, something troubled Eleanor. Her marriage had not been consummated yet, and with some advice from her uncle, the marriage was consummated on 16 April according to old German custom. After being on the road for so long, Eleanor soon learned that a battlefield was never far away.

Eleanor was also disappointed that she did not fall pregnant right away. Her doctors advised her to drink wine, but she hated wine and never drank it. In 1455, Eleanor became pregnant, and Eleanor settled at Neustadt for the birth. On 16 November 1455, Eleanor gave birth to a son named Christopher but tragically, the infant would live less than a year. It wasn’t until three years later that Eleanor became pregnant again. On 22 March 1459, she gave birth to another son – he would be named Maximilian and would one day succeed his father as Emperor. The following year, Eleanor gave birth to a daughter in Vienna, but the young girl – named Helena – also lived less than a year. On 16 March 1465, Eleanor gave birth to a daughter named Kunigunde, who would survive to adulthood. Her last child was a short-lived son named John, who was born on 9 August 1466 and who would also not live until his first birthday.

Eleanor was never the same after John’s birth, and she took the waters to regain her strength. This seemed to work at first, but young John’s death deeply affected her. She died on 3 September 1467 after a short illness. She was still only 32 years old. She wished to be buried next to her deceased children in the Cistercian monastery in Neustadt, and her wish was carried out. 1

Her husband did not remarry and he survived her for 26 years.

The post Eleanor of Portugal – The first Habsburg Empress appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 2, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The wedding of Wallis and Edward

On 3 June 1937, the former King Edward VIII finally reached the altar with the woman he had given up his throne for.

They had been reunited in France just one month prior. Just a few days after being reunited, the coronation of Edward’s brother took place, on the same date that had been planned for his own coronation. They listened to the ceremony on the radio. Wallis later wrote, “When we were briefly alone afterwards, he remarked in substance only this: ‘You must have no regrets – I have none. This much I know: what I know of happiness is for ever associated with you.’ In these first days together at Candé, we began to plan for the future.”1 That future included a “nice wedding present” from King George VI – who explicitly forbade Wallis from becoming a Royal Highness.

The wedding party included plenty of friends but, as expected, no member of the British Royal family attended. A telegram did come from King George VI and his wife, which said, “We are thinking of you with great affection on this your wedding day and send you every wish for future happiness much love.”2

Embed from Getty ImagesIn the morning, Wallis’s aunt Bessie helped her dress in a blue silk crepe outfit of a long skirt and a matching long-sleeved fitted jacket. She also wore wrist-length blue-crepe gloves and wore shoes in a matching blue shade. She chose to wear a small hat instead of a veil. Her something old was some antique lace stitched into her lingerie. Her something new was a gold coin minted for her husband’s coronation, which she wore in the heel of her shoe. The something borrowed came from aunt Bessie, and it was a lace handkerchief. The something blue was, of course, the outfit itself.

At half-past eleven, her friend Herman Rogers escorted Wallis down the staircase into the salon where the civil ceremony was to take place. The Duke was already waiting for her, wearing a suit of striped trousers, a grey waistcoat and a black cutaway. The ceremony was in French and had been rehearsed several times. Wallis answered “Oui” around 11.47 A.M., thus becoming the Duchess of Windsor. Around noon, the party moved to the music room where the religious ceremony took place. They entered separately, and Wallis walked down the aisle escorted by Herman Rogers to the sound of Handel’s wedding march. The ceremony was performed by Reverend Jardine.

One of the wedding guests later wrote, “It could be nothing but pitiable & tragic to see a King of England of only 6 months ago, an idolized King, married under those circumstances, & yet pathetic as it was, his manner was so simple and dignified & he was so sure of himself in his happiness that it gave something to the sad little service which it is hard to describe. He had tears running down his face. She also could not have done it better.3

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesA wedding luncheon was served in the dining room, and the meal consisted of lobster, salad, chicken à la King, and strawberries and cream. The wedding cake had six tiers and stood at three feet tall. After the cake had been cut by Wallis herself, she and Walter Monckton, the Duke’s adviser, went for a walk. He told her how much he sympathised with her position and that many people believed that she was responsible for the abdication. She replied, “Walter, don’t you think I have thought of all that? I think I can make him happy.”4

Another wedding guest recalled, “That marriage aged the Duchess overnight. People always thought she struck the best bargain, but she had to take the place of the Duke’s family, his country and his job. What a terrible, terrible responsibility. It was a sacred duty, but she was determined to treat him as he was, a former King of England.”5

That afternoon, the newlyweds travelled to Laroche-Migennes, where they boarded a private carriage that had been attached to the Simplon-Orient Express and headed towards Vienna on their honeymoon.

Wallis later wrote in her memoirs, “Here I shall say only that it was a supremely happy moment. All I had been through, the hurts I had suffered, were forgotten; by evening David and I were on our way to Austria.”6

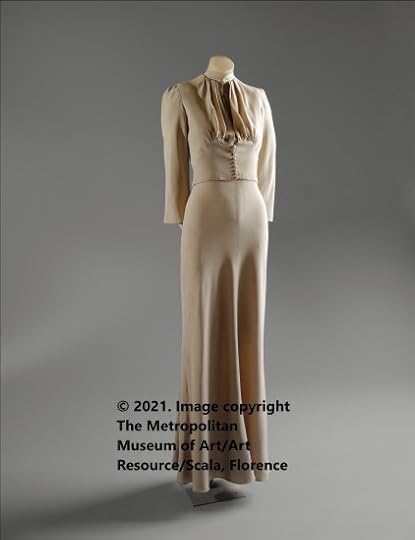

© 2021. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence

© 2021. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, FlorenceWallis donated her wedding dress to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1950 but the blue colour has faded since then. It is not currently on display.

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The wedding of Wallis and Edward appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 1, 2021

Lady Augusta Catherine Gordon-Lennox – Lady, Countess and Princess

Lady Augusta Catherine Gordon-Lennox was born on 14 January 1827 at Goodwood House as the daughter of Charles Gordon-Lennox, 5th Duke of Richmond and Lady Caroline Paget. Through her father, she was a descendant of King Charles II of England and Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth.

On 27 November 1851, Lady Auguste Catherine married Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar. He had been born in 1823 at Bushy House in London as the son of Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and his wife Princess Ida of Saxe-Meiningen, who was the sister of Queen Adelaide – consort of King William IV. Bushy Park was the residence of Queen Adelaide and King William (who were then still known as the Duke and Duchess of Clarence), and Princess Ida and her children were frequent visitors to England and Edward – their fourth child – was practically an Englishman. He served in the British Army, served as a Privy Councilor, and was a Field Marshall and Colonel of the First Life Guards. At the Battle of Quatre Bras and the Battle of Waterloo, he commanded the 2nd Brigade of the 2nd Dutch Division and became a Chief Commander of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army.

The marriage between the two was considered to be morganatic, and she was known as the Countess of Dornburg in Germany. Their wedding was described by Edward Stanley, 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley in a letter to his wife Henrietta Maria, “The marriage of LY. A. Lennox & Prince Ed. of Saxe Weimar came off this morning & I have seen Bessborough who was there who says there were an enormous number of people. The trousseau said to be most gorgeous, but they are only to have 2500 a year & she is to be called Ly. Augusta, not to go to Court, not recognised by the Family & the children are to be outcasts without a name.”1

The couple did not have any children together. Augusta Catherine appears several times in Memoirs of an ex-minister; an autobiography by James Harris, 3rd Earl of Malmesbury.2 In August 1861, he went to visit her after going to church, where he saw that seven babies were due to be christened. He related this to her, to which she replied with much amusement, “the clergyman ought to have used a watering-pot to sprinkle them.” They met again two weeks later when he wrote of opening a ball with her. On 6 September, he saw her again with her, “looking extremely disgusted at the rain, which was coming down in torrents.” In December, she was apparently at Court when Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert died. On 18 December, he wrote, “I got a letter from Princess Edward, giving a good account of the poor Queen, who bears her affliction most nobly.” On the 20th, he wrote, “The Princess says she [the Queen] has signed some papers, and seen Lord Granville.”

The Duke of Cambridge – the son of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, who was the seventh son of King George III and Queen Charlotte, and Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel – also wrote of her.3 In March 1881, he wrote, “The Princess was looking very well and happy. It is wonderful how well she and the Prince get on at Portsmouth.” In March 1885, he wrote of staying with the Princess and her husband in Portsmouth. In 1887, they were present at a large dinner following Queen Victoria’s Jubilee.

In 1885, Queen Victoria granted her official permission to share her husband’s princely title, and she was then known as Her Serene Highness Princess Edward of Saxe-Weimar. This title was only valid in England, and she remained known as the Countess of Dornburg in Germany. Some time in or before 1893, they were granted the style of Highness as they were then consistently referred to in the London Gazette.4 They were regularly invited to family events of the Royal Family, and they were present, for example, at the wedding of the future King George V and Queen Mary5 and the future Haakon VII of Norway and Queen Maud6. The couple lived at Portland Place in London.

The Princess was widowed on 16 November 1902. Edward had suffered from appendicitis and eventually succumbed to “congestion of the kidneys.”7 He was 79 years old. The Duke of Cambridge had visited the couple earlier in the year and had written, “Lunched with Princess Edward and afterwards went upstairs to the Prince’s room and was delighted to see him so much better, walking about his bedroom fairly, and evidently in better spirits. We had a nice talk together, and he seemed as pleased to see me, as I was to see him.”8 After her husband’s death, he wrote, ” To Portland Place to see poor dear Princess Edward, who was very calm and resigned, though overwhelmed with grief and sorrow at her great loss.” 9 Unfortunately, the Duke died shortly before Augusta Catherine.

Augusta Catherine survived her husband for about a year and a half. She died of pneumonia on 3 April 1904 at Portland Place.10 Her funeral took place “quietly” at Chichester Cathedral. The Prince of Wales (the future King George V) represented the King, and wreaths were sent by the King, the Queen, the Prince and Princess of Wales and many others. At the same time, a memorial service was held at St. Paul’s Church, Great Portland Street.11

The post Lady Augusta Catherine Gordon-Lennox – Lady, Countess and Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 30, 2021

Royal Wedding Recollections – King Alfonso XIII of Spain and Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg

On 31 May 1906, Madrid lavishly celebrated a royal wedding. King Alfonso XIII of Spain, who had been born posthumously to King Alfonso XII of Spain and Maria Christina of Austria, was set the marry the beautiful 18-year-old Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg. Victoria Eugenie was a granddaughter of Queen Victoria through her youngest daughter Princess Beatrice.

Neither knew that this could have been the day they both could have been killed. That day, Alfonso drove to the Pardo Palace, where Victoria Eugenie was staying, and together they travelled to the Ministery of Marine, where she was dressed in her bridal gown. The gown had been made by 40 seamstresses, who worked on it for 65 days, and it was “one of the most elaborate and exquisitely embroidered gowns ever seen at the Spanish Court.”1 She entered the Church of San Jeronimo to gasps from the guests.

Embed from Getty ImagesWilliam Miller Collier, the United States Ambassador to Spain, wrote, “To say that the bride was radiantly, superbly beautiful is not flattery. One could not say less and speak the truth.”2 The couple were married by the Archbishop of Toledo, and this was followed by a nuptial mass.

Embed from Getty ImagesAfter the religious ceremony, the newlyweds entered the state carriage, which was being pulled by eight plumed horses. Then began the ride to the Royal Palace through the crowds. Victoria Eugenie smiled and waved to the crowd, which shouted “Viva la Reina!” back at her. Shortly before arriving at the Royal Palace, the carriage suddenly stopped, and a floral bouquet was thrown from a nearby balcony. It fell just to the right of their carriage and exploded in a blinding flash – a bomb had been hidden inside it. In an instant, 37 people were killed, and many more were seriously injured.

Embed from Getty ImagesVictoria Eugenie had closed her eyes as the bomb exploded, but as she opened them again, she found herself not injured but in a heavily damaged carriage. Her new husband, too, had remained unharmed. Several of the horses that had been pulling their carriage were killed. One witness noted that one horse was “on the ground with its legs off and stomach ripped open. His great plumes lying in a mass of blood.”3 Victoria Eugenie’s satin wedding gown was soaked in blood. A guardsman riding next to the new Queen had been decapitated in the blast, and his blood had been blown all over her.

(public domain)

(public domain)Alfonso clasped her face in his hands and asked, “Are you wounded?” She answered, “No, no, I am not hurt. I swear it.” He then told her he believed a bomb had been thrown, and she replied, “So I had thought, but it does not matter. I will show you that I know how to be Queen.”4 The newlyweds alighted their broken carriage to board another one, and they were faced with a scene of carnage – mangled people and horses were on the ground. Victoria Eugenie remained calm and told a wounded equerry to take care of himself. People from the nearby British Embassy emerged and soon surrounded her carriage to escort it on foot to the Royal Palace.

Victoria Eugenie’s mind now began to race, and she repeatedly muttered, “I saw a man without any legs, I saw a man without any legs!”5 However, she knew she was now a Queen and had to act like one. The future Queen Mary (Mary of Teck) was one of the guests waiting at the Royal Palace, and she noted that “Nothing could have been braver than the young couple were, but what a beginning for her.”6 A French diplomat wrote, “Poor little King, poor little Queen… there has been no massacre parallel to this in the history of assassination attempts against monarchs… and the Queen will always keep the horrible impression of death and of the dead as a remembrance of her wedding day.”7

The wedding meal continued as normal as humanly possible, but not everyone thought Victoria Eugenie’s regal bearing was courageous and considered her reaction to be cold and distant. Her mother later wrote, “It does seem so sad, that a day which had begun so brightly for the young couple, and where they were just returning with such thankful happiness, at belonging at last entirely to one another, should have been overclouded by such a fearful disaster. God has indeed (been) merciful to have preserved them so miraculously, and this has only if possible deepened their love for one another and rendered the devotion and their people still more marked.”8

The following day, Alfonso and Victoria Eugenie drove out in an open car but naturally, she shrank back as crowds came close to her. She later wrote her own account of her wedding day, “My wedding day is a perfect nightmare to me & I positively shudder when I look back on it now. The bomb was so utterly unexpected that until it was all over, I did not realise what had happened, then even I was not frightened. It was only when I got into the other carriage that I saw such fearful horrors & then I knew what an awful danger we had gone through. My poor husband saw his best friend, a young officer, fall down dead beside our coach fearfully mutilated & that upset him very much. We are spending now a delicious time together in this lovely old Palace in the mountains & it all seems like a bad dream to us now.”9

The attacker, Mateu Morral, killed himself two days later.

The post Royal Wedding Recollections – King Alfonso XIII of Spain and Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 27, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The death of the Duke of Windsor

In the summer of 1971, the Duke began to lose his voice. He had been a regular smoker for many years, and it was perhaps no surprise that doctors discovered a tumour in his throat in the autumn. Wallis later said, “I told him to stop smoking all those cigarettes. We had some friends who had died of throat cancer. He said he started smoking a lot when he was travelling around as Prince of Wales, making so many speeches. He was always nervous about making speeches, and that’s why he smoked so much.”1 The tumour proved to be malignant and inoperable. Nevertheless, the Duke immediately began cobalt treatments.

The treatments seemed to push the cancer into remission, but when the Duke was in hospital in February 1972 for a hernia operation, his blood work showed that something was terribly wrong. The cancer was back, and the Duke underwent further treatments in hospital as the Duchess sat with him every afternoon. He was eventually released under the care of nurse Shanley and returned home to their villa. Nurse Shanley later recalled, “The Duke and Duchess were in love, and their interaction was like a young couple in love. There was a real togetherness about them, and a harmony which must have been there always because such virtues don’t suddenly come into being.”2

As the disease spread, the Duke became very thin. Wallis later said, “He pretended up to the last minute that he was in no danger, and I did the same. I think we both knew the other knew. How strange it was, trying to fool ourselves, to save the other from suffering.”3

On 10 May 1972, the Duke suffered a cardiac arrest, but nurse Shanley managed to bring him back. She alerted Dr Thin who ordered, “an intravenous drip with saline/glucose, vitamins and cardiac remedies to improve and maintain better heart function.”4

In May 1972, Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh were scheduled to visit Paris. By then, the Duke of Windsor was terminally ill. On 18 May, Wallis watched from the steps of their villa as the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, and Prince Charles arrived. She curtseyed deeply but almost lost her footing. The visit began with tea in the drawing-room before Wallis led the Queen upstairs to the boudoir. The dying Duke had received a blood transfusion that morning to have enough strength to meet his family.5

The Duke had insisted on getting dressed to meet his niece, but his clothes hung around his emaciated frame as he weighed less than six stone (84 lbs or 38 kg) at that point. He was on a drip, but his doctor had hidden the apparatus behind the chair in which the Duke was seated. The Duke rose slowly from the chair as The Queen entered to bow to her before kissing both cheeks. When she asked how he was, he replied, “Not so bad.”6

Wallis later told the Countess of Romanones, “The Queen’s face showed no compassion, no appreciation for his effort, his respect. Her manner as much as states that she had not intended to honour him with a visit, but that she was simply covering appearances by coming here because he was dying and it was known that she was in Paris.”7 The nurse on duty recalled that the Queen spoke amiably with her uncle. The nurse said, “As the Duchess brought Prince Charles in [the Duke’s] face lit up, and he started asking him about the navy… but, after a few minutes, I saw the Duke’s throat convulse, and he began coughing. He mentioned me to wheel him away, the Royal Family stood up, and I had the feeling that this was his way of avoiding any formal goodbyes. It had all been brief, immensely cordial, and very important to him, but he had no reserves of strength left.”8 The whole visit has lasted just 30 minutes.

The Windsors’ secretary later said, “That visit by the Queen was very healing. Nobody knows exactly what was said, but it was extremely important. The Duke always said that he loved the Queen.”9

The day after the Queen’s visit, the Duke seemed to improve a little, but on 25 May, he was unable to leave his bed. The following day, Wallis called their American physician Dr Arthur Antonucci to come to Paris to see the Duke. He dropped everything and was in Paris late that afternoon. After examining the Duke and conferring with Dr Thin and nurse Shanley, he told Wallis that there was nothing he could do. From then on, Wallis barely left the room.

Late Saturday night, the Duke told Wallis to get some rest. He said, “Darling, go to bed and rest. Oonagh (nurse Shanley) will look after me.”10 Just a few hours later, around 2.20 a.m., the Duke of Windsor died in his sleep. His nurse went to wake up Wallis, who kissed his forehead and cupped his face while saying, “My David, my David… You look so lovely.”11 The news was released by Buckingham Palace, and the text of a telegram sent by the Queen to Wallis was also released. “I know that my people will always remember him with gratitude and great affection and that his services to them in peace, and he will never be forgotten. I am so glad that I was able to see him in Paris ten days ago.”12

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The death of the Duke of Windsor appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 26, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Denying the style of HRH: “A nice wedding present” (Part two)

Wallis later wrote, “The distinction did not seem particularly important to me. David (Edward) had given up the most exalted of titles. It hardly seemed worthwhile to me to quibble over a distinction in a lesser one. But nothing in the aftermath of the Abdication hurt David more than that gratuitous thrust. In his eyes, it was an ultimate slur upon his wife, and, therefore, upon himself. He could not bring himself to wholly to blame his brother, who, he knew, had bowed to strong pressure. But this action made for a coolness between them thereafter.”1

The Duke of Windsor would continue his quest to secure the style of Her Royal Highness for Wallis. In November 1942, he wrote to Winston Churchill and urged that “after five and a half years, the question of restoring to the Duchess her royal status should be clarified.” He had been requested by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to submit the names of local candidates for the New Year honours list, and he believed Wallis was the perfect candidate. “I am now asking you, as Prime Minister, to submit to the King that he restores the Duchess’ royal rank at the coming New Year not only as an act of justice and courtesy to his sister-in-law but also as a gesture in recognition of her two years of public service in the Bahamas. The occasion would seem opportune from all angles for correcting an unwarranted step.”2 King George VI replied to Winston Churchill that he was “sure it would be a mistake to reopen this matter… I am quite ready to leave the question in abeyance for the time being, but I must tell you quite honestly that I do not trust the Duchess’s loyalty.”3 Privately, he added, “I have consulted my family, who share these views.”4

In 1949, the Duke of Windsor consulted Viscount Jowitt for a legal opinion on the question of her title. He had also given his opinion in 1937 when he went on to declare that “the Duchess of Windsor is, by virtue of her membership of the Royal family, entitled in the same way as other royal duchesses, to be known by the style and title of ‘Her Royal Highness.'” This time he back-peddled slightly and added, “that the marks of respect which the subject pays to Royal personages are, as I said, in no source a legal obligation. They are simply a matter of good manners.”5 He pointed out that the matter could only be formally resolved by fresh Letters Patent and since these would not be issued by the King unless on the advice of his ministers, it was unlikely that these would be issued at all. However, Viscount Jowitt later wrote to Tommy Lascelles6 that he still believed a legal mistake had been made. “In reality, he remained HRH notwithstanding the Abdication, and the attribute to which he was entitled would automatically pass to his wife.”7

When the Duke of Windsor tried to arrange a meeting with Prime Minister Attlee, Queen Mary wrote to King George VI, “I cannot tell you how grieved I am at your brother being so tiresome about HRH. Giving her this title would be fatal, and after all these years, I fear lest people think we condoned this dreadful marriage which has been such a blow to us all in every way.”8 King George himself wrote to the Duke that there was no possibility of the issue being reconsidered. He wrote, “I made your wife a Duchess despite what happened in 1936. You should be grateful to me for this. But you are not.”9

The new QueenWhen King George VI died in 1952, the Duke went to London alone as the Duchess was not welcome. She was quite worried that he would use the situation to press the HRH issue. She wrote to him, “Now that the door has been opened a crack, try and get your foot in, in the hope of making it open even wider in the future because that is best for WE… I should also say how difficult things have been for us and that also we have gone out of our way to keep our way of life dignified which has not been easy due to the expense of running a correct house in keeping with your position as a brother of the King of England. And leave it there. Do not mention or ask for anything regarding recognition of me. I am sure you can win her (Queen Elizabeth II) over to a more friendly attitude.”10 Nevertheless, he raised the issue with the new Queen, but she too would not budge on the issue.

In December 1963, Wallis was interviewed by Susan Barnes, who asked her if she believed she would ever become a Royal Highness. “Never!” she answered. “I don’t mind. There are a great many things I have had to learn not to give any importance to… I don’t know, but I think the refusal to give me equal rank with my husband may have been done to make things difficult for us. It is difficult – because people are puzzled about what to do with me. At parties. At any time. They don’t understand being married to Mr Smith and being called Mrs Jones. And I know it hurts my husband… I know that he has been hurt very deeply… I don’t mind for myself. I’ve lived without this title for twenty-five years. And I’m still married to this man!”11

In 1967, Philip M. Thomas published an article in Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage called “The Duchess of Windsor – Her Position reappraised.” He concluded, “Not merely in justice, but as public recognition of the honour of the Duke, steps should be taken without further delay to right this most flagrant act of discrimination in the whole history of our dynasty.”12

The issue would follow the Duke and Duchess to the grave – literally. While the Duke’s tombstone lists him as “HRH The Prince Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David Duke of Windsor”, Wallis’ tombstone simply reads “Wallis Duchess of Windsor.”

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Denying the style of HRH: “A nice wedding present” (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Denying the style of HRH: “A nice wedding present” (Part one)

“This most flagrant act of discrimination in the whole history of our dynasty.” 1

On 27 May 1937, just a few days before Wallis and Edward were due to be married, a letter arrived from King George VI with “not very good news.”2 Edward then learned that while Wallis would become Duchess of Windsor upon marriage, she would be denied the usual style of Her Royal Highness. He commented, “This is a nice wedding present.”3

The letterIn a letter from King George VI to his brother, he explained that he had consulted the heads of the Dominion and Empire countries and that they had advised that they considered that he had lost all royal rank when he abdicated the throne and was no longer entitled to use the title of Prince or the style of HRH. He then explained that he intended to recreate him His Royal Highness The Prince Edward, the Duke of Windsor, adding that he could not and would not extend the style to Wallis, who would only be known as the Duchess of Windsor.

Status of the husbandThis decision was against the royal practice, and British common law as a wife automatically takes her status from her husband unless her own rank is higher. When Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon married the Duke of York (future King George VI), this statement was released: “In accordance with the settled general rule that a wife takes the status of her husband Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon on her marriage has become Her Royal Highness the Duchess of York with the status of a Princess.”4 The Duke of Windsor had been assured by his brother that Wallis would become part of the family upon marriage. When he learned of the u-turn, he declared, “My brother promised me there would be no trouble over the trouble! He promised me!”5 King George VI had faced considerable opposition from both his wife and his mother. They simply would not receive Wallis and demanded that he would find a way to deprive her of becoming an HRH.

Finding a wayKing George VI discussed the issue with the British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, as he believed that once Wallis became a Royal Highness, she would remain one for life even after divorce. He was either unaware of the complexity of the issue or (deliberately?) misinformed. Perhaps he believed that as the sovereign, as Fountain of Honours, all titles, awards and peerages are said to descend via the throne through the monarch. Still, he had no active role in the acquisition of the style of HRH by any of the other royal wives by marriage. King George VI continued to find a way to deprive the style of HRH from Wallis, even asking the Home Secretary, the Lord Chancellor and the Attorney-General to find some legal means.

He asked Stanley Baldwin, “Is she a fit and proper to become a Royal Highness after what she has done in this country; and would the country understand it if she became one automatically on marriage? I and my family and Queen Mary all feel that it would be a great mistake to acknowledge Mrs Simpson as a suitable person to become Royal. The Monarchy has been degraded quite enough already.”6

It was then decided that the only way forward was to deprive the Duke of Windsor of his royal rank and then restore it with restrictions. Letters Patent were drawn up and declared that Edward VIII had, upon abdicating the throne, lost all royal rank and status. King George VI would recreate him a Royal Duke with the style of HRH. He added that the 1917 Letters Patent issued by King George V restricted the style of Royal Highness to those in the lineal succession to the throne, but the Duke of Windsor was no longer eligible for the throne. According to the new Letters Patent, King George VI was actually making an exception in granting him the style of HRH and therefore claimed also to be able to restrict it to him alone.

The final argumentHowever, King George VI was obliged to seek the advice of his minister, and he was not empowered to alter royal titles, according to the Statute of Westminster, without consulting the Dominions. Not wanting a different opinion, King George VI wrote to Stanley Baldwin telling him exactly what he wished the advice to be. On 26 May 1937, the discussion and ratification of the Letters Patent that created the former King a Royal Prince and allowing him to withhold the style of HRH from Wallis were included in Stanley Baldwin’s last Cabinet meeting as Prime Minister. Two days later, the official announcement appeared in the London Gazette.7

Thus, King George VI and his advisers presented the argument. The former King had, according to them, lost all royal rank upon abdication, and the new King was perfectly entitled to restore this rank and to restrict the style of HRH to him alone. However…

Losing royal rankThe former King had never lost his royal rank. On 5 February 1864, Queen Victoria had issued Letters Patent saying, “that besides the Children of Sovereigns of these Realms, the Children of the Sons of any Sovereign of Great Britain and Ireland shall have and at all times hold and enjoy the title, style and attribute of “Royal Highness,” with their titular dignity of Prince or Princess prefixed to their representative Christian names.”8 Queen Victoria’s Letters Patent were later confirmed by King George V in 1917.9

The only way the former King’s royal rank or style of HRH could have been taken away would have been through the issuance of Special Letters Patent, which specifically deprived him of these. This was never done, not even during the abdication process. Upon his abdication, he immediately became a Prince of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with the qualification of Royal Highness pursuant to the 1917 Letters Patent, confirmed by his own father. King George VI had even – inadvertently – recognised his brother’s royal rank immediately after his abdication by instructing Sir John Reith to introduce him as His Royal Highness Prince Edward before his speech to the nation.

It was obvious that King George VI was using the denial of the style of HRH for the Duchess as a way to keep both of them out of the country. The Duke had vowed never to return to England unless Wallis was an HRH. King George VI had acted against common law to deprive her of the style of Royal Highness.

As expected, the Duke of Windsor considered it to be a great insult to his wife.10 Eventually, their household staff in France referred to her as “Son Altesse Royale.”11 However, the story doesn’t end there.

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Denying the style of HRH: “A nice wedding present” (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 25, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis & Queen Mary (Part two)

Queen Mary is perhaps most remembered in the tale of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor as the one at whose insistence the style of Her Royal Highness was withheld from the Duchess. King George VI had promised his brother that Wallis would take her rightful place in the family; the Duke was outraged to learn that Wallis would be deprived of the style shortly before they were to be married. Both Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth declared that they would not receive Wallis and demanded of King George VI that he find a way to deprive her of the style of Her Royal Highness. Queen Mary’s biographer, who studied her private papers, later admitted that the decision had been “at the insistence of Queen Mary.”1 Queen Mary was clearly chanelling her anger at her son’s decision at the person she held responsible – Wallis. Although it was against common law to do so, Wallis was indeed denied the style.

On 3 June 1937, Wallis and Edward were married in France – it was also the late King’s birthday. Queen Mary wrote in her diary, “Alas! The wedding day in France of David (Edward) & Mrs Warfield!”2 At the beginning of September, the Duke and Duchess of Kent were nearby on holiday, but they had received strict instructions not to visit them. When the Duke of Windsor learned of this, he wrote to his mother, “I, unfortunately, know from George that you and Elizabeth instigated the somewhat sordid and much-publicized episode of the Kents to visit us… I am at a loss to know how to write to you and further to see how any form of correspondence can give pleasure to either of us under these circumstances… It is a great sorrow and disappointment to me to have my mother thus cast out her eldest son.”3

When the Second World War came to France, the Duke and Duchess briefly returned to England, but only the Duke was able to see his family. As Queen Elizabeth wondered what to do about “Mrs S,” Winston Churchill had the thankless task of arranging something for the returning Duke and Duchess. He arranged for a naval guard of honour at Portsmouth, and as they descended the gangway, they were saluted by the Royal Marine Band. However, they did not even have a place to stay, and they spent the first night with Sir William James, commander in chief at Portsmouth. They then stayed over at the Metcalfes – Fruity Metcalfe was a friend and the Duke’s former equerry – but requests for accommodation were denied by the Palace, and a car for their use was also out of the question. Queen Mary had not seen her son in three years, but she deliberately avoided him.

It wasn’t until 1944 that Wallis wrote to Queen Mary. By then, the Duke of Windsor was Governor of the Bahamas, and the Archbishop of Canterbury had appointed the Bishop of Nassau to a post in London. In an attempt to repair the relationship between mother and son, Wallis suggested to Queen Mary that if she wished to learn about her son’s life, she might speak to the Bishop. The Bishop was indeed invited by Queen Mary, and he spoke glowingly about the work that the Duke, and the Duchess too, had been doing. Although Wallis had received no reply, Queen Mary later wrote a rare letter to her son which ended with, “I send a kind message to your wife.”4 It was the first time she had acknowledged Wallis as his wife, and it left the Duke astounded. Nevertheless, when the war was over, and the Duke and Duchess returned to France, both Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth still refused to receive Wallis. Wallis began to refer to Queen Elizabeth as “that fat Scotch cook, the Dowdy Duchess and the Monster of Glamis.”5

On 6 February 1952, King George VI died in his sleep, which cemented the hate Queen Elizabeth had for the Duchess. The Duke and Duchess were in New York at the time, and the Duke immediately planned to return home. He was firmly told that Wallis would not be received by any of the three Queens. The following year, the same awkward situation was repeated. On 24 March 1953, Queen Mary died. Wallis reportedly burst into tears upon hearing the news of her mother-in-law’s death. She would keep a photograph of the Queen on a table in her bedroom for the rest of her life. The Duke returned home with his sister Mary, Princess Royal and wrote to Wallis from the ship shortly before Queen Mary’s death, “The bulletins from Marlborough House proclaim the old lady’s condition to be slightly improved. Ice in place of blood in the veins must be a fine preservative… Mary seems to have become more human with age and has revealed a few interesting family bits of gossip.”6

Queen Mary had remained stoic until the end. She had never written to Wallis, and Christmas cards were directed to the Duke alone. After attending his mother’s funeral, he wrote to Wallis, “My sadness was mixed with incredulity that any mother could have been so hard and cruel towards her eldest son for so many years and yet so demanding at the end without relenting a scrap. I’m afraid the fluids in her veins have always been as icy cold as they now are in death.”7 Wallis commented sadly, “He spent his entire life trying to win her approval. Now it’s too late.”8

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis & Queen Mary (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis & Queen Mary (Part one)

Queen Mary (born Mary of Teck) was the wife of King George V of the United Kingdom and the mother of King Edward VIII. As such, she was the mother-in-law of the Duchess of Windsor, but she never accepted Wallis and barely acknowledged her.

Their first meeting happened before Wallis was even involved with the future King Edward VIII. On 10 June 1931, Wallis was officially presented at court before the King and Queen. It had involved jumping through quite a few hoops as, for many years, a divorced person could not be presented at court. This had recently changed, and now one could be presented at court if they could prove that they were the injured, blameless party. Legal proof had to be provided to the office of the Lord Chamberlain, and so Wallis obtained copies of her divorce decree from the United States, and she forwarded them to St. James’s Palace. Wallis borrowed a dress from her friend Consuelo Thaw and train, feathers and a fan from Thelma Furness, Viscountess Furness. She bought a large cross to wear around her neck and elbow-length white gloves. That day, Wallis swept into a deep curtsey before King George V and Queen Mary, but they exchanged no words. It had lasted less than a minute.

When Wallis was firmly established as the favourite several years later, she and her husband Ernest received an invitation to the wedding of Prince George and Princess Marina (The Duke and Duchess of Kent). Two days before the wedding, they were also invited to a state ball for the bride and groom. Edward quickly sought her out and presented her to Prince Paul of Yugoslavia and then took her over to his parents. He said, “I want to introduce you to a great friend of mine.” Wallis curtseyed deep before the King, and he took her hand in his. She then turned to Queen Mary and curtseyed again. Queen Mary, too shook her hand. By then, both the King and Queen were well aware of Wallis’s presence in their son’s life. It would be the only time Wallis had a proper meeting with her future parents-in-law. Wallis later wrote, “It was the briefest of encounters – a few words of perfunctory greeting, an exchange of meaningless pleasantries, and we moved away. But I was impressed by Their Majesties great gift for making everyone they met, however casually, feel at ease in their presence.”1

After King George V’s death and the accession of Edward, Mary remained rather quiet on the topic of Wallis. She later said, “I have not liked to talk to David (Edward) about his affair with Mrs Simpson, in the first place because I don’t want to give the impression of interfering in his private life, and also because he is the most obstinate of all my sons. To oppose him over anything is only to make him more determined to do it. At present, he is utterly infatuated, but my great hope is that violent infatuations usually wear off.”2 In May 1936, Wallis’ name appeared in the court circular as having attended a dinner with the King. Queen Mary showed it to Mabell Ogilvy, Countess of Airlie – Lady of the Bedchamber – and said, “He gives Mrs Simpson the most beautiful jewels. I am so afraid that he may ask me to receive her.”3

On 16 November 1936, the King dined with his mother and his sister and informed them that he intended to marry Wallis. As she feared, he asked Queen Mary to receive Wallis, which she refused. When he asked her why, she replied, “Because she is an adventuress!”4 Queen Mary may have believed that Wallis was actively working to marry the King, which she was not. He later wrote, “To my mother, the monarchy was something sacred and the Sovereign a personage apart. The word ‘duty’ fell between us. But there could be no questions of my shirking my duty.”5 For Queen Mary, there were just two options: marry Wallis and leave the country, or not marry and remain as King. When he informed them in December that the abdication was to take place the following day, Queen Mary was overheard exclaiming, “To give up all that for this!”6

The day after the abdication, Edward made his now-famous radio speech and then returned to the Royal Lodge to say his goodbyes. Lord Brownlow, Lord-in-waiting to the former King, recalled, “Edward went up to Queen Mary and kissed her on both hands and then on both cheeks. She was as cold as ice. She just looked at him.”7 The following day, Queen Mary released a message for the British people, “I need not speak to you of the distress which fills a mother’s heart when I think that my dear son has deemed it to be his duty to lay down his charge and that the reign, which had begun with so much hope and promise, has so suddenly ended. I know that you will realize what it has cost him to come to this decision; and that, remembering the years in which he tried so eagerly to serve and help his Country and Empire, you will ever keep a grateful remembrance of him in your hearts. I commend to you his brother, summoned so unexpectedly and in circumstances so painful, to take his place… With him, I commend my dear daughter-in-law, who will be his Queen.”8

The public may have been critical of the King’s abdication; the following humiliations did not seem correct. The Archbishop of Canterbury publically denounced the King, and his speech received the support of Queen Mary, who wrote to congratulate him on his speech. Others in the family followed suit and Queen Maud of Norway (Edward’s aunt) wrote of Wallis, “Wish something would happen to her!” She described Wallis as “one bad woman who has hypnotized him.” She later added, “I hear that every English and French person gets up at Monte Carlo whenever she comes into a place. Hope she will feel it.” His great-aunt Louise, Duchess of Argyll, repeated a joke that Wallis must spend a lot of time in the bathroom as it would be the “only throne she would ever sit on.”9

Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth would soon close ranks altogether. Henry Channon, a politician, wrote of Queen Mary, “Certainly she and the Court group hate Wallis Simpson to the point of hysteria, and are taking up the wrong attitude; why persecute her now that all is over? Why not let the Duke of Windsor, who has given up so much, be happy? They would be better advised to be civil if it beyond their courage to be cordial.” The following year, Queen Mary answered in response to a question as to whether the Duke of Windsor would return to his country, “Not until he comes to my funeral.”10

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis & Queen Mary (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.