Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 121

March 17, 2022

Book Review: Empress Alexandra: The Special Relationship Between Russia’s Last Tsarina and Queen Victoria by Melanie Clegg

*review copy*

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia was a granddaughter of Queen Victoria through her daughter Alice, who would tragically die young. Queen Victoria would always be especially close to Alice’s children, and they often visited her in England.

Empress Alexandra: The Special Relationship Between Russia’s Last Tsarina and Queen Victoria actually begins with the birth of Princess Alice. I thought this was a bit much and irrelevant to the story, even though the author explains her reasoning behind this in the book. Alexandra (Alix) isn’t even born until a third of the book later, and we finally get to the point. Queen Victoria was known to be quite present, and while this may have been seen as an honour from the matriarch of the family, experiencing it could be very stifling. As she watched her beautiful granddaughter grow into a young family, Alexandra kept her budding romance with the future Nicholas II of Russia under wraps as she had seen the distrust Queen Victoria had shown towards Russia when her sister Elisabeth married Grand Duke Sergei.

Despite her grandmother’s protests, Alexandra became Empress of Russia as Nicolas’s wife, and letters between Russia and England went back and forth as Alexandra embarked on motherhood. Unfortunately, much of the surviving correspondence is one-sided, and we don’t read much from Alexandra’s point of view. Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 is the natural stopping point of this book.

Overall, I enjoyed the book, though I could have done without the first third of the book. Also, grab Coryne Hall’s Queen Victoria and The Romanovs: Sixty Years of Mutual Distrust (UK & US) for a broader overview.

Empress Alexandra: The Special Relationship Between Russia’s Last Tsarina and Queen Victoria by Melanie Clegg is available now in the UK and the US.

The post Book Review: Empress Alexandra: The Special Relationship Between Russia’s Last Tsarina and Queen Victoria by Melanie Clegg appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 16, 2022

Maria of Austria – The widowed Empress (Part three)

It was expected that Maria would act as a discreet advisor to her son who should not decide on “serious matters in the council of state until they were made known to the empress and her advice sought.”1 He was, after all, young and inexperienced.

One of Rudolf’s first acts jointly with his mother was to decide the fate of his younger brothers and give them ecclesiastical offices. Albert was to receive the cardinal’s hat and the Archbishopric of Toledo from his uncle King Philip II. However, while the cardinal’s hat was quickly granted, he would have to wait 20 years for the Archbishopric of Toledo. Young Wenceslaus was appointed the right of succession of the Grand Priory of the Order of Malta, but he died suddenly a year later at the age of 17. Matthias was not inclined towards an ecclesiastical office, but the younger Maximilian readily accepted.

There were also three daughters who lived at home. Elisabeth, who had married King Charles IX France and had been widowed in 1574, had returned home following her husband’s death. And then there were Margaret and Eleonore. She began to hunt for a suitor for Eleanore and discussed the possibility of her marriage to Charles Emmanuel, the future Duke of Savoy, but Eleanore tragically died in 1580 at the age of 11. By contrast, she wouldn’t even consider marriage for Margaret, “as she is ugly and disastrous […] and so it is more convenient for her to be with me for my whole life and do what I tell her.”2 Elisabeth, as a dowager Queen, demanded autonomy from her mother, but several suitors were considered for her. Nevertheless, Elisabeth refused all offers.

Maria had expressed the wish to return to Spain and live a religious life shortly after her husband’s death. Her new role of dowager empress did not work well for her, and she was depressed and tired. However, both her brother and her son discouraged her from this but as her relationship with her son deteriorated, her wish only became stronger. Finally, in 1581, she received permission to return home. Her daughter Anna, who had been married to her uncle, had died the previous year at the age of 30.

Maria and her daughter Margaret arrived at the port of Collioure on 12 December 1581, 30 years after she had left Spain. Despite her strong wish to retire, Philip hoped he could change her mind as he was in need of someone to act in his absence. They finally met in May 1582, and Philip later wrote, “You can imagine how much she and I rejoiced when we saw each other, having lived 26 years without seeing each other.”3 Maria was also reunited with her son Albert, whom she had not seen for 12 years as he lived at the Spanish court. Maria travelled on to Lisbon, where she would spend a year, continually refusing the accept the regency over Portugal. She also resisted Philip’s attempt to marry off Margaret because “she was crippled apart from lame and had a very different face and appearance from the others and was quite deformed.”4 She did wish for another marriage though – the marriage of her son Rudolf to Philip’s daughter Isabella Clara Eugenia.

Finally, after much wrangling, Margaret was allowed to join the monastery of the Descalzas, and Maria would be allowed to accompany her for the rest of her life. Margaret professed in January 1584 under the name Sister Margarita de la Cruz. Unfortunately, her wish for the marriage of her son was not fulfilled, and he would remain unmarried for the rest of his life. Maria lived outside of the cloister in the quarters that had once been used by sister Joanna, who had founded the monastery. She received papal dispensations to enter the monastery and share the monastic life. While there, she had a demanding daily schedule that consisted of being read about the life of the saint of the day, prayers with her daughter Margaret, some free time and more time for prayers in the evening. Until her health started to deteriorate at the end of the 1590s, she was able to move around freely in Madrid. Sometimes Philip invited her on country and hunting trips. She also maintained extensive correspondence with her other children.

On 13 September 1598, King Philip II died and was succeeded by his only surviving son, who now became King Philip III. Maria was very close to her grandson, and she now hoped for a more prominent role. He presented himself at Descalzas to receive her blessing shortly after his father’s funeral, and her niece Margaret of Austria was to become Philip’s wife. However, the influence of the Duke of Lerma meant that there would be no prominent role for Maria.

By the middle of February 1603, Maria came down with a cold that she found hard to shake. Her grandson Philip had wanted to visit her, but his newborn daughter, also named Maria, was dying. It soon became apparent that the elder Maria was also nearing the end of her life. Her daughter Margaret fulfilled her destiny “by helping her to die well and being by her side, and when she expired, [Margaret] closed her eyes and left.”5 It was 26 February 1603 at five in the morning, and Maria had lived to the age of 74.

The post Maria of Austria – The widowed Empress (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 15, 2022

Maria of Austria – The Ambassadress (Part two)

In August 1556, Maria’s father abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor in favour of his brother Ferdinand, having already abdicated as King of Spain earlier in favour of Philip. Charles died in retirement two years later. By 1559, the family had moved to the nearby city of Wiener Neustadt as they grew out of their lodgings in Vienna. Their new castle was located right by a massive park, which allowed for the family’s favourite pastime of hunting. However, Maximilian was itching for more responsibility, but he was kept on a tight leash by his overbearing and sickly father. On 9 March 1561, Maria gave birth to another son – named Wenceslaus. This was followed by the births of two short-lived sons and a short-lived daughter in 1562, 1564 and 1565.

On 21 September 1562, Maria was crowned Queen of Bohemia – her husband had been crowned the day before. Maria wore a white dress with gold with sleeves described as “old Spanish… and the decoration and veil on her head were also Spanish.”1 Her young daughters Anne and Elisabeth were able to see the ceremony and “were repeatedly allowed by the dukes [sic] to move ahead so that they would be better able to see.”2 Maria was anointed with oil and received the sceptre, orb and crown associated with the office of the Queen of Bohemia. She briefly stumbled on a fold in the carpet on her way out of the cathedral and was helped up by her sister-in-law Anna. Unfortunately, they did not have much time to enjoy the celebrations surrounding the coronation. Prague was consumed by plague, and they needed to move on to Frankfurt for the imperial election.

In November, Maximilian was chosen as the King of the Romans and thus as his father’s successor to the Imperial crown. Maria was now not only a Queen but could look towards becoming an Empress as well. They were also crowned as King and Queen of Hungary the following year. On 25 July 1564, Maria’s father-in-law died “as if in sleep without any pains.”3 Ferdinand had remained lucid until the end and had kissed the portrait of his late wife as his family gathered around him.4 Maximilian was elected as the new Holy Roman Emperor two years later.

Ferdinand left five unmarried daughters who needed to be taken care of. Margrete – at 28 years old – had already been given permission to enter a convent and her sisters Magdalena and Helene joined her in seeking a religious life. Barbara married Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio in 1565, while Joanna married Francesco I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, later that same year. Now that the older generation was taken care of, Maria’s daughters would be next. Finally, in 1567 and 1568, Maria gave birth to her last two daughters. Margaret survived to adulthood, but Eleanore would die at the age of 11.

The deaths of Maria’s brother King Philip’s only son Carlos and Philip’s third wife Elisabeth in 1568 led to a change in groom for Maria’s eldest daughter Anna. Instead of her first cousin, she would now marry her uncle Philip herself and become Queen of Spain. Maximilian later confessed that he loved Anna “more than all the others together.”5 Not much later, the betrothal between King Charles IX of France and Maria’s younger daughter Elisabeth was also confirmed.

As Holy Roman Empress, Maria’s role evolved as she now was requested to act as a mediator between successive popes, her brother Philip II and her husband, Maximilian. Maximilian later wrote that “she would make a great Embassy on her part and on mine.”6 Nevertheless, the final decision always remained with her husband, and he stated, “If I wanted to do everything my wife […] wants, I would have a lot to do.”7 Her daily life as Empress was rather monotonous, and her contact was limited to her inner circle. However, she did have a leading role in ceremonial events. She attended mass daily with her household servants and her children. She often dined with her husband, and they also often spent their evenings together.

In September 1676, Maximilian fell ill, but the doctors were unable to agree on a treatment. He was in a lot of pain and even summoned a woman named Magdalena Streicher, who was known as a healer. He became more depressed as the days passed and had heart palpitations. Despite his illness, he continued the business of government until the very end. He refused to take the last rites of the Catholic Church, much to Maria’s horror. When he died at 9 in the morning on 12 October 1576, Maria was at Mass, even though she had barely moved from his bedside the previous weeks. The shock of his death, while she was absent, was devastating for her.

Maximilian was succeeded by their 24-year-old son Rudolf. And while he and his siblings appeared in public shortly after Maximilian’s death, Maria remained secluded. She had fainted upon hearing the news of her husband’s death and had to be taken unconscious to her rooms, where she remained for a long time. Until the funeral in March, Maria spent her days in prayer and “when she is alone, it is my understanding that she never stops crying.”8 She would later confess that she feared that she might follow in the footsteps of her grandmother Queen Joanna of Castile, who suffered a mental breakdown at the death of her husband.9

Maria decided that her husband would be buried in the St Vitus Cathedral, and she would stay in the castle of Prague on the same grounds as the cathedral to be near her husband.

Part three coming soon.

The post Maria of Austria – The Ambassadress (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 13, 2022

Maria of Austria – A future Empress (Part one)

Maria of Austria was born on 21 June 1528 as the second child and eldest daughter of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and Isabella of Portugal. She was baptised immediately, probably in the Church of San Miguel de Sagra. Of her seven siblings, only her elder brother Philip (the future King Philip II of Spain) and her younger sister Joanna (born in 1535) survived to adulthood.

Maria was under the care of a Portuguese wet nurse by the name of Maria de Leite and several trusted ladies-in-waiting. They were all under the supervision of the first lady of the bedchamber, Guiomar de Melo. Until 1535, both Maria and Philip were raised in the household of their mother, Isabella. Their first years were spent in several different cities. There didn’t seem to have been much of an education happening there as Philip could neither read nor write at the age of seven. It is unclear if this was also the case for Maria, but Philip was quickly brought up to speed after this, though he never quite liked his studies.

In 1535, Philip was moved to his own household, but the siblings remained close. They continued to play and study together, kept birds as pets and played musical instruments. They eventually came to share a tutor, as the one assigned to Maria was only at court briefly. Maria was not “as devoted to letters as her brother.”1 By the end of 1535, Maria could read Spanish, and by the following year, she could write adequately. Though not particularly interested in grammar and letters, Maria appears to have been quite fond of music and dance in her childhood. She learned the Spanish and French styles of dance, which she displayed during special court occasions.

The death of her mother following childbirth in 1539 disrupted the peaceful family Maria had enjoyed thus far. Her father Charles was often away, and Maria and her younger sister Joanna were put in the care of trusted aristocrats in Arévalo. Maria was not happy there, and when her father came to visit in November 1539, she spoke out. Barely a year after their arrival, the girls were moved to Ocaña. Their stay there was brief, too, as Maria began to suffer from a skin condition. They eventually settled in Madrid, Alcalá de Henares and Guadalajara. Although their households were kept strictly apart, Maria was able to see her brother Philip under supervision.

When Maria was 15 years old, Philip married their first cousin Maria Manuela of Portugal, but she would tragically die in childbirth two years later. Her young son Carlos survived the birth. Several ladies-in-waiting in Maria Manuela’s household then joined the household of Maria and Joanna. Young Carlos also went to live with his aunts, and this also meant that Philip’s visits became even more frequent. Much to their father’s dismay, Philip began a relationship with one of their ladies-in-waiting. Meanwhile, Maria’s education was down to half an hour a day due to her lack of interest, and her handwriting was atrocious. However, she did still enjoy music and was getting into embroidery. And most importantly, her Catholic faith was unwavering.

Several suitors for her hand were considered over the years. Finally, in 1545, she was informed that she would marry the Duke of Orleans (Charles – the third son of King Francis I of France and Claude of France), which she accepted as she considered it her duty. However, he died suddenly that November. The next most suitable choice was her first cousin Maximilian, the eldest son of her father’s younger brother Ferdinand. Maximilian was called to Spain “for his upbringing and experience.”2 The marriage agreements were signed on 24 April 1548.

On 13 September 1548, Maximilian arrived in Vallodolid, and the couple were officially betrothed that same night. The following day, the nuptial mass took place. The couple were appointed governors of the Iberian kingdoms. Maximilian was accused of neglecting his wife in the first year of their marriage, and there were rumours that their marriage was not consummated. However, he was suffering from quartan fever, which left him weak until early 1549. The question of consummation was soon out of the way, too, as by early 1549, Maria was pregnant with their first child.

On 2 November 1549, a daughter named Anna was born, and she was to become her uncle Philip’s fourth wife in 1570. On 17 April 1551, Maria gave birth to a son named Ferdinand, but the boy died just a few months later. After serving as regents for Philip, Maria and Maximilian moved to Vienna in late 1551. One member of their entourage was an elephant named Suleiman, which had been a wedding gift from King John III of Portugal.3 Their solemn entry into Vienna finally took place on 7 May 1552 with elephant Suleiman in the entourage. They would divide their time between Vienna and Wiener Neustadt in the following years, with shorter stays in Prague, Linz and Innsbruck. Maria had a good relationship with her father-in-law Ferdinand, but she would not know her mother-in-law, Anne, as she had died in 1547. Her lack of language skills also severely limited her at court. She never learned to speak German and did not know Latin or French. The only other language besides Spanish she knew was Italian, but she still asked for a written text of speeches given in Italian so that she could understand it better.

On 18 July 1552, Maria gave birth to her first surviving son, Rudolf. A second surviving son, Ernest, was born on 15 June 1553. A daughter named Elisabeth was born on 5 July 1554, followed by a short-lived daughter named Maria on 27 July 1555. The nursery was filling up fast, but the lodgings in Vienna left a lot to be desired. It wasn’t until 1559 that the royal apartments in the Hofburg were completed, and by then, Maria had given birth to four more sons (of which three survived to adulthood): Matthias in 1557, a stillborn son in 1557, Maximilian in 1558 and Albert in 1559. Maria closely monitored her growing brood, and they spent a lot of time together, especially in their early years. Her daughters would remain at home for their education, but most of her sons were eventually sent to the court of Madrid to be raised by her brother Philip.

In 1556, Maria and Maximilian travelled to Brussels to meet with their fathers and other family members to discuss the future of the Habsburg dynasty. The succession to the Imperial throne had been determined in 1551, but this appeared to be unworkable, and a new alternative had to be found. It was determined that Maria’s brother Philip would renounce his claims to the empire and lands in central Europe and would receive the Iberian kingdoms. This would allow Ferdinand, and eventually Maximilian and Maria, to assume the Imperial throne. Maria’s father also suggested that her youngest daughter Elisabeth should be betrothed to the future King Charles IX of France to enforce peace with France, while their eldest daughter Anne was to be betrothed to her first cousin Carlos.

Part two coming soon.

The post Maria of Austria – A future Empress (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 11, 2022

Maria Anna of Savoy – A good and gentle being (Part two)

During the revolution of 1848, Prince Metternich fled abroad, and Ferdinand tried to make concessions by granting the press freedom and promising a constitution. However, the revolution flared up again, and in early October 1848, Ferdinand and Maria Anna settled in the Prince-Archbishop’s residence in Olomouc. Prince Felix Schwarzenberg was appointed Minister-President of the Austrian Empire, and he worked behind the scenes with Archduchess Sophie, who now saw her chance to place her son on the throne. She persuaded her unambitious husband to waive his succession rights in favour of her son. On 2 December 1848, at the residence in Olomouc, Ferdinand abdicated the throne as his nephew and successor knelt before him. Maria Anna bent down to him to pull him close, hugged him and kissed him. Ferdinand told the new Emperor, “God bless you! Be good, and God will protect you.”1

After the ceremony, Ferdinand and Maria Anna retired to their apartments. Ferdinand wrote in his diary, “Soon afterwards, my dear wife and I heard Holy Mass in the chapel of the archbishop’s residence. Afterwards, my dear wife and I packed our belongings.”2 They were to retain their imperial status. After packing their belongings, a carriage brought them to the train station, where a special train waited to take them to Prague. Maria Anna was reportedly quite glad to be free of the official duties and was now able to devote herself entirely to her husband.

They began to divide their time between Prague, Schloss Ploschkowitz and Reichstadt. Maria Anna also often visited Italy for her health, and she was able to see her family there. Her closest friend during this time was Countess Therese Pålffy. Maria Anna maintained her own court in Prague with two ladies-in-waiting, a secretary, valets, maids etc.

In 1856, Ferdinand and Maria Anna celebrated their silver wedding anniversary, and the event was attended by Emperor Franz Joseph and his wife Elisabeth in Prague. They lived a retired life, and ironically, Ferdinand would outlive many members of his family, even Archduchess Sophie, who was 13 years younger than him. As he became older, he spent a large part of his time in bed, lovingly cared for by Maria Anna. When he lay dying in June 1875, Emperor Franz Joseph came to Prague to find Ferdinand sleeping in his wheelchair. He returned home without having spoken to him. The following day, Ferdinand was dressed, and he had something to eat before listening to a Haydn symphony performed for him. This stopped when he had a coughing fit, and he was taken to bed.

He was given the last rites that same day and died peacefully around 2.45 p.m. He was 83 years old. Ferdinand’s body was returned home to Vienna, where he was interred in the Imperial Crypt. Maria Anna was left well-cared for with an annual pension of 120,000 guilders, of which a large part was spent on charity with a special focus on women’s orders who taught girls. After her husband’s death, Maria Anna lived in even stricter isolation than before – and it could almost be considered a monastic life with prayers filling her days. Her only visitors were members of the Imperial Family or other family members. Her will had been drawn up in 1874 when Ferdinand was still alive. She wrote, “I am closing this will by expressing my heartfelt thanks to Emperor Ferdinand for the kindness he has shown me over so many years.”3

In May 1884, newspapers reported that Maria Anna was seriously ill. After a short illness and a hernia operation, Maria Anna died on 4 May, at 5.10 p.m. in Prague Castle. The official cause of death was pneumonia. The secluded Empress had requested a humble funeral, which took place on 10 May. She was buried beside her husband in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna.

The post Maria Anna of Savoy – A good and gentle being (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 10, 2022

Maria Anna of Savoy – A good and gentle being (Part one)

Maria Anna of Savoy was born on 19 September 1803 as the daughter of King Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia and Archduchess Maria Teresa of Austria-Este (a granddaughter of Empress Maria Theresa). Maria Anna had a twin sister named Maria Teresa, who became Duchess of Parma and Piacenza. The twin sisters were born in Rome and were baptised by Pope Pius VII. Two other sisters survived to adulthood, but the only son of her parents’ marriage tragically died of smallpox before his third birthday. In the family, Maria Anna was known as Pia.

At the time of her birth, the family was in exile because of Napoleon. The family was not able to return to Turin until Napoleon’s fall in 1814. Maria Anna grew up during these years of turmoil, but her education was not neglected. As was usual, her education focussed on learning several foreign languages and on religion. Maria Anna would always prefer to write in French. In 1821, her father abdicated in favour of his younger brother Charles Felix. The former King died in 1824.

Maria Anna remained unmarried until the age of 27. Two of her sisters had already married in 1812 and 1820, while her younger sister (with an age difference of 9 years) married in 1832. In 1831, the Austrian Emperor Francis I (known as Francis II before the dissolution of the Holy Roman Emperor) was looking for a bride for his eldest son; the future Emperor Ferdinand I. Ferdinand suffered from hydrocephalus, epilepsy and a speech impediment. This was most likely genetic as his parents were double first cousins. Ferdinand’s younger brother Franz Karl had married Sophie of Bavaria in 1824, and she had recently given birth to the future Emperor Franz Joseph. It seemed unlikely that Ferdinand would even be able to consummate the marriage as he was reported to have up to 20 epileptic attacks a day. Still, if he were to produce a son with Maria Anna, he would have taken precedence over the newborn Franz Joseph. In any case, it was hoped that the marriage between Maria Anna and Ferdinand would bring the two monarchies closer together.

On 12 February 1831, the proxy wedding took place in the cathedral in Turin with her uncle Charles Felix standing in for the groom. It was also her uncle who accompanied her to Milan the following day. Maria Anna travelled incognito under the name Countess von Habsburg to Milan, where she was officially handed over. Her uncle died shortly after returning home. Maria Anna travelled on towards Wiener Neustadt, where she would finally meet Ferdinand.

It is not clear what the two thought of each other upon their first meeting. Afterwards, Ferdinand returned to the Hofburg, while Maria Anna went to Schönbrunn. On 27 February, she made a solemn entry into Vienna with the usual ceremonies. She was met by Ferdinand, who led her inside. At 3.30 p.m., the couple were married in the Joseph’s Chapel in the Hofburg, and the ceremony was performed by Archduke Rudolf – a son of Emperor Leopold II – who was the Archbishop of Olomouc. Archduchess Sophie later wrote, “We cannot thank Heaven enough for having sent us such a good and gentle being.”1 Ferdinand’s stepmother Caroline Augusta wrote, “Ferdinand is always very satisfied. . . Marianne seems to be very attached to him. She seems very sensitive, I don’t think he could have made a better choice.”2

Although she was well-received at court, she was unable to speak German and never learned it properly. She always spoke French and was known to be an introverted and humble person. She got on well with her new husband and worried about his health. However, this also meant that she was more a nurse than a wife to him. He continued to suffer from frequent epileptic attacks. Her first experiences with her husband’s attacks must have been scary for her. In December 1832, he was so ill with his attacks that he received the last rites. It was a Christmas miracle that he survived. Maria Anna herself was not a healthy woman either. Surviving documents show that she was described medications on a near-weekly basis for stomach issues and the like. She also went on extended stays in the spas of Italy.

On 2 March 1835, Ferdinand’s father Francis died at the age of 67. He had left his son several letters advising him to follow the advice of Prince Metternich, the Chancellor of the Austrian Empire. Nevertheless, many doubted that Ferdinand was capable of ruling at all, and indeed, he was rarely politically active. As Empress, Maria Anna was described with the words, “Her dignity, her politeness and her agility correspond exactly to the image of the first lady of the empire. She seldom dances, but when she does, she moves with incredible grace and grace, so that everyone is completely carried away by her.” 3 As Emperor and Empress, they devoted themselves to charity, and Ferdinand let politics take its course, relying on the advice of others.

Part two coming soon.

The post Maria Anna of Savoy – A good and gentle being (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 8, 2022

Judith of Evreux – A Norman in Sicily

In the mid-eleventh century, many Norman mercenaries arrived in southern Italy and began to take it from Byzantine control. Among them were the Hauteville family. Although minor nobles back in Normandy, they would soon rule over all of southern Italy. The Hautevilles continued to intermarry with other Normans who accompanied them. One of these first Norman noblewomen in southern Italy was Judith of Evreux – a relative of the Dukes of Normandy.

Early life in Normandy

Judith of Evreux was born around 1042 to William of Evreux and Hawisa of Echauffour. William was a grandson of Richard I, Duke of Normandy. Before marrying William, Hawisa was married to the Norman baron, Robert of Grandmesnil. Hawisa bore Robert six children, three sons and three daughters, before Robert’s death. Judith was the only known child Hawisa had with William.

Around 1055, Roger, the youngest of the large brood of Hauteville brothers, was traveling around Normandy on his way to Italy. The small Hauteville lands could not be divided between the various brothers, so the younger ones were looking for greater fortunes in southern Italy. Around this time, Roger and Judith met for the first time at her father’s lands in Evreux. Roger was immediately taken with Judith, but as the youngest son of a minor baron, he was far outranked by her. Roger continued on to southern Italy and continued to conquer lands with his brothers.

From Normandy to Italy

Judith’s half-brother, Robert of Grandmesnil, was elected Abbot of Saint Evroul in 1159. However, Robert eventually found himself opposed to Duke William of Normandy – the future William the Conqueror. In 1061, he traveled to Rome to seek the aid of the Pope. When Robert returned, he discovered that William had chosen a new Abbot of Saint Evroul during his absence. He had some relatives who were among the Normans who settled in southern Italy and they invited him to settle with them there.

Meanwhile, Judith and one of her half-sisters, Anna, were living at the convent of Ouche, which was attached to Saint Evroul. According to one chronicle, they had taken the veil, but it seems more likely that Judith was living there for the time being. When Robert left for Italy, Judith and Anna decided to join him. They departed for Rome in the spring of 1061. Meanwhile, Roger de Hauteville and his brothers were invading Sicily. The invasion was successful, and the Normans began to build fortresses in Sicily. Judith’s brother, Robert was given a monastery on the Calabrian coast dedicated to Saint Euphemia.

Marriage

When Roger learned of Judith’s arrival, he immediately went to see her. Robert also invited Roger. Now that Roger had lands of his own, he was of fitting rank to marry Judith. Roger and Judith married in Mileto, in southern Italy in early January 1062. However, Roger was still busy with his campaigns and soon left for Sicily, while Judith remained in Mileto. That summer, Roger returned to Judith and brought her with him to Sicily.

Winning over Sicily

Roger left Judith in the Sicilian town of Troina with a small garrison. He then headed out into Arab-controlled Sicily. Soon, the people of Troina began to rebel against the Normans and held Judith hostage. A message was sent to Roger, who arrived the next morning. Roger was able to rescue Judith, but Troina remained under siege. Roger and Judith remained together during the four-month siege. It happened during a cold winter, and the food supply was tight. Roger and Judith shared a cloak for warmth. Eventually, there was so little food, that some of the knights even ate their own warhorses. After four long months, Roger was able to regain control of Troina, and put down the rebellion. He then returned to Calabria to get horses and supplies for his men. He left Judith in charge of Troina.

Judith continued to inspect the work on the town’s fortifications. She also reassured the men that her husband would reward their efforts upon his return. After Roger’s return, Judith moved to San Marco d’Alunzio in Sicily, possibly in order to start a family. Judith eventually gave birth to at least four daughters; Matilda, Emma, Adelaide, and one who was possibly named Flandina. She was not known to have any sons. However, Roger’s son, Godfrey, Count of Ragusa, is thought to have belonged to her. Godfrey might have been born to Roger’s second wife, Eremburga of Mortain, or most likely, was illegitimate.

In late 1071, Roger started to besiege Palermo, Sicily’s largest city. That year he was recognized as the first Count of Sicily, and Judith became the first Countess of Sicily. However, it would not be for nearly another sixty years before Sicily became a Kingdom. Judith only enjoyed her status as Countess of Sicily for five years. She died in 1076, and was buried at her brother’s monastery of Saint Euphemia. Roger married twice more, firstly to Erembuga of Mortain, and then to Adelaide del Vastro, who gave him the sons who succeeded him.

All four of Judith’s daughters made beneficial marriages. Flandina first married Hugh of Jersey, and secondly Henry del Vastro. Matilda first married Robert, Count of Eu, and then Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse. Adelaide married Henry, Count of Mount Saint Angelo. Emma was originally set to marry Philip I, King of France, but he chose Bertrade de Montfort instead. Emma then went on to marry firstly, William, Count of Clermont, and secondly, Rudolf, Count of Montescaglioso.

Sources:

Alio, Jacqueline; Queens of Sicily, 1061-1266

The post Judith of Evreux – A Norman in Sicily appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 7, 2022

Americans and royal titles

Several Americans have been born with royal titles or have gained titles through marriage. The United States Consitution says that Americans cannot accept titles from foreign powers without the consent of Congress. What does that mean for the Americans who hold titles?

Article I, Section 9, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution, also called the Foreign Emoluments Clause, states: “No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.”

The U.S. Constitution’s Title of Nobility Clause does not explicitly ban an American citizen from being royal or a king. It only states that the U.S. government cannot grant any title of nobility.

Now, for those who are born on American soil to royal parents – they are automatically American citizens by being born on U.S. soil; they are also citizens of their kingdoms. In the case of Princess Leonore of Sweden, she was born in the United States and holds dual U.S./Swedish citizenship. Her grandfather, King Carl XVI Gustaf, gave her the duchy of Gotland and the title of Princess of Sweden. The American government did not object. Nor have they objected to other similar situations with royals from other countries.

However, specifically, people have argued about Archie and Lili Mountbatten-Windsor holding future titles as Americans. Does the Constitution ban that?

Several royals have been born in and outside the United States and hold royal titles. The U.S. Congress has made no issue of that. The Prince and Princess of Monaco’s first child, Princess Caroline, was born on 23 January 1957. Before the birth of Caroline, the United States consul in Nice, France, requested that the U.S. State Department make a ruling on the citizenship status of Grace, who retained her American citizenship, and Rainer’s children. Reportedly, the consul was told that their children would be born dual citizens of both the United States and Monaco. Their second child, Prince Albert, was born on 14 March 1958. Their third child, Princess Stéphanie, was born on 1 February 1965. All three children were born in the Prince’s Palace of Monaco.

Reigning Prince Albert II of Monaco held American citizenship until he was 21, when he renounced it. He could not be the Sovereign Prince of Monaco and a U.S. citizen. There has been no announcement of his two sisters ever renouncing their American citizenship.

The only monarch to ever be born in the United States, the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand (or Rama IX) was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while his father was studying at Harvard University. Thailand does not allow dual citizenship, so the King had to renounce this U.S. citizenship by the time he turned 18.

It should be noted that U.S. Presidents have received foreign honours from the U.K. (Presidents Reagan, Bush and Eisenhower) and other foreign powers. For example, President Bill Clinton, President George W. Bush, President Barack Obama and President Donald Trump all received the Order of King Abdulaziz from the Saudi monarch. Congress did not object to any of these, nor have they objected to private citizens (think Bobe Hope, Bill and Melinda Gates and Angelina Jolie) receiving orders from foreign powers.

Attorneys have argued over the matter, and many believe the Constitution is only referring to the U.S. government handing out royal titles or gifts – not that of foreign monarchies.

Now, if Archie and Lilie become Prince Archie and Princess Lili when their grandfather, Prince Charles, ascends the throne, neither of the two could hold public office in the United States while also holding the title of prince/princess. They would have to give up their title to run for public office – unless Congress consents to them holding their titles and running for public office. But this is unlikely.

However, there is a constitutional amendment that has never been passed that would revoke U.S. citizenship from any American who accepts a foreign title of nobility. The amendment was proposed in 1810, and any constitutional amendment must require a 2/3 vote of both Houses of Congress AND be ratified by 3/4 of state assemblies. Twelve states have voted to approve the amendment; however, no votes have taken place since 1814.

The post Americans and royal titles appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 6, 2022

Empress Dowager Dou – The duplicitous Empress

(Not to be confused with Empress Dowager Dou Yifang)

Empress Dowager Dou has been known in history as one of China’s most villainous empresses. Chroniclers emphasized how all of her evil actions were pardoned by her merciful adopted son.[1] Historian Keith McMahon even labelled her as “The Conniving Empress.”[2] She killed off her rivals and promoted her self-serving brothers. Yet, Empress Dowager Dou was a capable regent, and she had two military victories in her reign. However, her accomplishments were forgotten while her vile reputation remained. Thus, Empress Dowager Dou will continue to remain in history as an evil empress.[3]

Empress Dowager Dou was born around 62 C.E. Her first name is unknown.[4] Her family was from Pinglang in Fufeng (somewhere between the modern-day cities of Xianyang and Xingping in Shaanxi Province).[5] Her father was Dou Xun, and her mother was Princess Biyang, the granddaughter of Emperor Guangwu and Empress Guo Shengtong.[6] Thus, Dou was a descendant of the imperial family. However, the family fell from prominence when her father was found to be abusing his power by mistreating peasants.[7] This so disgusted Emperor Ming that he had Dou’s father executed. Despite these setbacks, Dou was a very bright young girl.[8] She impressed her family when she could read at six years old.[9]

In 77 C.E., Dou and her sister were selected to become concubines to Emperor Zhang. Emperor Zhang was very eager to see Dou because he had heard about her beauty before.[10] It turned out that she lived up to his expectations because historians describe her to be an elegant beauty.[11] He was smitten with her at first sight. Even Empress Dowager Ma was pleased with her.[12] She seemed to be a gentle and devoted daughter-in-law.[13] Thus, the following year in 78 C.E., Lady Dou was promoted to Empress with the Empress Dowager’s approval. Her sister was made Worthy Lady (the rank below Empress), and their father was honoured with the posthumous title of Marquis Si of Ancheng.[14]

Even though Dou was invested as Empress, she was still not happy with her situation. She was still childless.[15] Historians said that she became a jealous woman and hated her palace concubines who had a son with her husband.[16] Chroniclers also stated that she spent her free time getting rid of her rivals.[17] Her first victim was Lady Song, who gave birth to a son named Liu Qing.[18] Empress Dou accused Lady Song of witchcraft, and the concubine was forced to commit suicide.[19]

After Lady Song‘s death, Empress Dou decided to eliminate Lady Liang. She wrote an anonymous letter to Lady Liang’s father accusing him of a crime he did not commit.[20] Lady Liang’s father was executed.[21] Lady Liang and her entire family were forced into exile in Juizhen (modern-day Vietnam).[22] Lady Liang died shortly after she arrived at her destination.[23] Empress Dou adopted Lady Liang’s son, Liu Zhao (the future Emperor He).[24] Empress Dou also continued to promote her brothers to high court positions.[25]

In 88 C.E., Emperor Zhang died at the age of thirty-three.[26] The ten-year-old Liu Zhao ascended the throne as Emperor He.[27] Dou became Empress Dowager and was made regent.[28] As regent, Empress Dowager Dou had complete control of the nation.[29] She made her mother the Grand Princess.[30] She also made her brother Dou Xian in charge of all the confidential military affairs.[31] Yet, Dou Xian was very ruthless and kept eliminating his rivals, which included many prominent officials and noblemen.[32] Empress Dowager Dou was about to punish her brother, but Dou Xian bargained with her by organizing a military expedition against the powerful northern Xiongnu (known in the West as the Huns).[33]

In 89 C.E., he led the military expedition, and they achieved a military victory. The Han killed more than 10,000 of the northern Xiongnu army.[34] Over two hundred thousand Xiongnu surrendered.[35] Pleased with his victory, the conceited Dou Xian and his comrade general, Geng Bing, engraved their victory on stones before they returned to Luoyang (the capital city).[36] The victory only made Dou Xian more arrogant, but Empress Dowager Dou did not punish him. Instead, she made him the highest-ranking Han general.[37] This meant that he was even higher than the Prime Minister![38] She was very pleased with her brother because this victory over the Xiongnu greatly increased her reputation.[39]

In 91, C.E., Dou Xian went on a second military expedition against the Xiongnu and was also victorious.[40] She also promoted her two other brothers, Dou Jing and Dou Duo. All three of her brothers continued to abuse their power by mistreating the commoners and fabricating accusations against the officials and nobles they disliked.[41] They were greatly hated. It was said that street vendors and businessmen ran away when they happened to catch sight of them.[42]

In 92 C.E., Emperor He was so disgusted with his adopted mother’s brothers that he formed a coup d’etat to get rid of them.[43] Emperor He executed her three brothers and many of their supporters.[44] One of these supporters was Ban Gu, the author of History of The Han Dynasty.[45] The Dou Brothers’ family were exiled to modern-day Vietnam.[46] Emperor He was now in power, and Empress Dowager Dou was forced to hand over the imperial seals.[47]

Empress Dowager Dou lived for five more years. During those years, she was lonely and depressed.[48] She died in 97 C.E. She was around the age of thirty-five.[49] Before she could be buried, a memorial was submitted requesting Empress Dowager Dou to be stripped of her imperial title because of all the harm she caused Worthy Lady Liang and her family.[50] Several officials also agreed for Empress Dowager Dou to be stripped of her title and not to let her be buried beside her late husband.[51] After much contemplation, Emperor He issued an edict that decreed:

“Although [Empress Dowager Dou] has broken the law, she was often modest in her demands. After serving her for ten years, I am deeply aware of her kindness to me. In Book of Rites, there is no record of a son downgrading someone of an older generation. Because of my love for her, as a grateful man, and a filial son, I cannot part from her and her kindness; on principle, I cannot treat her badly. There is also the case of Empress Dowager Shangguan who was not dethroned. Therefore, I will not consider this request.”[52]

Empress Dowager Dou was buried in the Jing Tomb beside her late husband, Emperor Zhang.[53] The Empress’s greatest fault was in promoting her self-serving brothers. This had made her hated by her contemporaries. Yet, in the end, she was shown mercy in death. Empress Dowager Dou will always be remembered for her ruthlessness.

Sources:

Fanzhong, Y. (2015). Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century. (B. B. Peterson, Ed.; A. Xinli, Trans..). London: Routledge.

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Yang, H. (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge.

[1]Yang, p. 128

[2] McMahon, p. 128

[3] Yang, p. 128

[4] Yang, p. 127

[5] Fanzhong, p. 103

[6] Fanzhong, pp. 103-104

[7] Fanzhong, p. 104

[8] Yang, p. 127

[9] Yang, p. 127

[10] Yang, 127

[11] Yang, p. 127

[12] Yang, p. 127

[13] Yang, p. 127

[14]Yang, p. 127

[15] McMahon, p. 102

[16] Yang, p. 127

[17]Yang, p. 127

[18] Fanzhong, p. 104

[19] Fanzhong, p. 104; Yang, p. 127; McMahon, p. 103

[20] Fanzhong, p. 105; Yang, p. 127

[21] Fanzhong, p. 105; Yang, p. 127

[22] Fanzhong, p. 105; Yang, pp. 127-128

[23]Fanzhong, p. 105; Yang, pp. 127-128; McMahon, p. 103

[24] Fanzhong, p. 105; Yang, p. 128; McMahon, p. 103

[25] Yang, p. 128

[26] Fanzhong, p. 1-5

[27] Fanzhong, p. 105

[28] Fanzhong, p. 105; Yang, p. 128; McMahon, p. 103

[29] Fanzhong, p. 105

[30] Yang, p. 128

[31] Fanzhong, p. 128

[32] Fanzhong,p p. 105-106

[33] Fanzhong, pp. 105-106

[34] Fanzhong, p. 106

[35] Fanzhong, p. 106

[36] Fanzhong, p. 106

[37] Fanzhong, p. 106

[38] Fanzhong, p. 106

[39] Fanzhong, p. 106

[40] Fanzhong, p. 107

[41] Fanzhong, p.107

[42] Fanzhong, p. 107

[43] Fanzhong, p. 107

[44] McMahon, p. 103

[45] McMahon, p. 103

[46] Fanzhong, p. 107

[47] Fanzhong, p. 107

[48] Fanzhong, p. 107

[49] Fanzhong, p. 107

[50] Yang, p. 128

[51] Yang, p. 128

[52] Yang, p. 128

[53]Yang, p. 128

The post Empress Dowager Dou – The duplicitous Empress appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 4, 2022

The Year of Empress Elisabeth – Sisi & her daughter Sophie

In the early hours of 5 March 1855, the 17-year-old Empress Elisabeth of Austria went into labour with her first child. Her mother-in-law Archduchess Sophie sat outside the bedchamber with her needlework as her son Franz Joseph went back and forth between his wife and his mother. She was allowed to join them inside around 11 a.m. when the labour pains became stronger.

She later wrote, “Sisi held my son’s hand between her own two and once kissed it with a lively and respectful tenderness; this was so touching and made him weep; he kissed her ceaselessly, comforted her and lamented with her, and look at me at every pain to see if it satisfied me. When they grew stronger each time and the birth began, I told him so, to give Sisi and my son new courage. I held the dear child’s head, the chamber woman Pilat held her knees, and the midwife held her from behind. Finally, after a few good long labour pains, the head appeared, and immediately after that, the child was born (after three o’clock) and cried like a six-week-old baby. The young mother, with an expression of touching bliss, said to me, ‘oh, now everything is all right, now I don’t mind how much I suffered.’ The Emperor burst into tears, he and Sisi did not stop kissing each other, and they embraced me with the liveliest tenderness. Sisi looked at the child with delight, and she and the young father were full of care for the child, a big, strong girl.”1

After the little baby washed and dressed, Archduchess Sophie held her granddaughter and sat next to Elisabeth’s bed with Franz Joseph, where they waited until Elisabeth fell asleep. The infant was named Sophie for her grandmother and godmother, although Elisabeth was not consulted on this. However, it was customary to name children for their grandparents. The idea that the child was taken from her immediately after birth can be disproven with a letter Elisabeth wrote three weeks later, “My little one is already very charming and gives the Emperor and me enormous joy. At first, it seemed a little strange to me to have a baby of my own; it is like an entirely new joy, and I have the little one with me all day long, except when she is carried for a walk, which happens often while the fine weather holds.”2

In August 1855, just five months after the birth of little Sophie, Elisabeth wrote to her mother-in-law, who was in Ischl at the time, “Dear mother-in-law, after the Emperor told me of your wish, I would like to give you news of us, so I am sending you these lines to tell you that we are very well, also the little one, who is always so cheerful and gets stronger and more developed each day.”3 This doesn’t seem to come from a mother who was never allowed to see her children, although it was true that the nursery was placed near Archduchess Sophie’s rooms. Archduchess Sophie adored the little girl and recorded every little detail about her in her diary.

Just over a year later, Elisabeth gave birth to a second daughter who was named Gisela, and by that summer, the nursery was moved to another room upon Elisabeth’s insistence. Sophie was not even in Vienna at the time and had to be reassured by her son. In the winter of 1856-1857, little Sophie travelled with her parents to northern Italy, where the provinces were restless. Elisabeth had been unwilling to leave her children for so long and managed to bring along Sophie, saying that the Italian air would be good for the delicate child. It was a difficult few months, but Franz Joseph praised Elisabeth.

Just a few weeks after returning home from Italy, the Emperor and Empress went to visit Hungary. This time, Elisabeth insisted on bringing both Sophie and Gisela along. Unfortunately, just before the departure, Sophie became ill with a fever a slight case of diarrhoea. The doctors assured them that the symptoms were related to teething, and they all left together. After arriving in the castle of Budapest, the ten-month-old Gisela also became ill. But while Gisela recovered, Sophie continued to worsen. Franz Joseph wrote to his mother, “She slept only 1 1/2 hours all night, is very nervous, and keeps crying constantly, it’s enough to break your heart.”4 Their personal physician Dr Seeburger managed to reassure Franz Joseph and Elisabeth, and Franz Joseph even went out hunting. The trip further into Hungary went ahead but was broken off after five days in Debrecen when Sophie grew even worse.

Elisabeth spent 11 hours watching her young daughter struggle to breathe. On 29 May 1857, Franz Joseph telegraphed his mother, “Our little one is an angel in heaven. After a long struggle, she finally passed away at nine-thirty. We are devastated.”5 Elisabeth may have feared returning to Vienna and her mother-in-law, but Sophie had known the loss of a daughter as well, and she did not reproach Elisabeth for taking little Sophie along despite her protests.

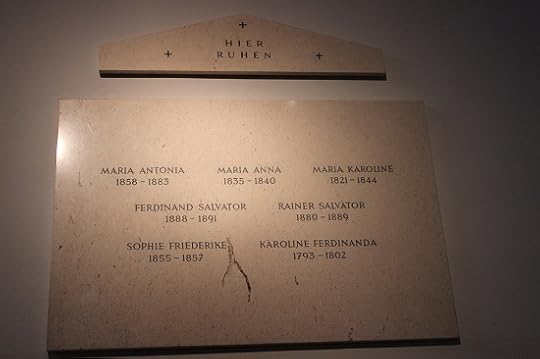

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe young girl was interred in a wall in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna, and for the entire summer, Elisabeth drove down from Laxenburg in a carriage with the blinds drawn to go into the crypt and pray. Elisabeth was inconsolable at little Sophie’s death and withdrew from everyone, including her surviving daughter. Her mother was summoned to Vienna, who brought along three of Elisabeth’s younger sisters. Ludovika later wrote, “The company of her young, cheerful sisters seemed to do Sisi much good; since parting from us was so hard for her, she made me promise to come to Ischl if at all possible.”6

Six months after Sophie’s death, Franz Joseph wrote, “Poor Sisi is much affected by all the memories that confront her here [in Vienna] on all sides, and she cries a great deal. Yesterday Gisela, visiting with Sisi, sat in the little red armchair of our poor little one, which stands in the den, and at that, both of us cried, but Gisela, happy at this new place of honour, kept laughing so charmingly.”7

The post The Year of Empress Elisabeth – Sisi & her daughter Sophie appeared first on History of Royal Women.