Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 117

May 5, 2022

Dangereuse de l’Isle Bouchard – Mistress to William IX, Duke of Aquitaine

Dangereuse was born around 1079 into a noble family to parents Bartholomew de l’Isle Bouchard and his wife Gerberge in the centre of modern-day France. Unfortunately, due to the family not being extremely important and the events taking place so long ago, there is little detail on her early life. However, it seems her first name was actually Amauberge, and Dangereuse was a sobriquet that came later.

In 1109, she appeared on record, and it seems that some years before this, Dangereuse had married. Her husband was Aimery I, Viscount of Châtellerault, and he was a vassal to William IX, the Duke of Aquitaine. Dangereuse had five children with her husband; Hugh, Raoul, Amable, Aois, and Aénor.

Dangereuse, or Dangerosa as she is sometimes called, crossed paths with William IX, Duke of Aquitaine, a few years into her marriage. This was probably just an innocent meeting as the Duke was her husband’s overlord. However, Dangereuse had a reputation for not caring at all what people thought of her, and William was rather popular with women as he was a troubadour (a lyrical poet) as well as a Duke, so maybe the pair were drawn to each other during this initial meeting.

In around 1115, we begin to hear that William had kidnapped a woman called Amauberg, the wife of one of his vassals. He is said to have taken Amauberg by force to La Maubergeonne castle, which was in Poitiers, where he forced her to stay and become his mistress. Due to the name of the tower that she lived in, people called her La Maubergeonne. This sort of kidnapping was common during the medieval period, and many women suffered greatly after being kidnapped and forced into marriages. However, it is widely recorded that Amauberg was actually part of this plan all along. It seems that her husband Aimery was too afraid of the Duke to fight back, and so Amauberg and William became a long-term couple, and she began to be known as Dangereuse.

William, however, had a wife, Phillipa of Toulouse, who returned from time in her homeland to discover her husband had moved Dangereuse into their palace. Phillipa was outraged and tried her best to gather support from courtiers to have the woman removed, but nobody would back her as they had to stay loyal to their lord. A Papal legate even pleaded with William to separate from Dangereuse, but William simply mocked the legate, and Phillipa had to leave her home to live in Fontevrault Abbey, where she died in 1118.

After the death of Phillipa, Ermengarde of Anjou visited William’s court. She was his first wife, but their marriage fell apart after three years passed without any children being born to the couple. Strangely, Ermengarde and Phillipa had grown close as friends, and now with Phillipa dead, Ermengarde wished to take revenge on William for mistreating her. William ignored Ermengarde’s pleas that he remove Dangereuse from his home and restore her instead, so Ermengarde took her complaints to the pope. Pope Calixtus II heard Ermengarde’s woes at the council of Reims, and it seemed that he agreed that William should be excommunicated from the church in 1119. However, it looks like he never actually went through with this, as by 1120, William was fully readmitted into the church.

It seemed that nothing could stop Dangereuse and William from doing whatever they wished, and over the years, they had three children together called Henri, Adelaide and Sybille. William also had legitimate children with his wife Phillipa, and the relationship with Dangereuse greatly damaged the bond with his oldest son, also called William.

In order to heal the relationship with his son, Duke William arranged for his son to marry Dangereuse’s daughter from her marriage to Aimery. It is not clear why this decision was made, but supposedly this would force William to accept Dangereuse and would also be a great match for Dangereuse’s daughter as it was greatly above her rank.

In 1121, Aénor de Châtellerault, Dangereuse’s daughter, married William, Duke William’s son. The couple had three children together: Eleanor, Petronilla and William, though William died in childhood.

In 1127, William IX died, and his son became William X, Duke of Aquitaine. Nothing more was heard of his seductive mistress Dangereuse after this other than the date of her death in 1151.

The relationship between William IX and his mistress Dangereuse left its mark on history as their granddaughter (Duke William X’s daughter) became the heir to Aquitaine. She is remembered widely as Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of medieval Europe’s most powerful women. She was married to King Louis VII of France and later King Henry II England; her children went on to rule over much of Europe.

The post Dangereuse de l’Isle Bouchard – Mistress to William IX, Duke of Aquitaine appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 3, 2022

Empress Wang – The usurper’s daughter

Empress Wang happened to be the daughter of one of China’s most notorious usurpers. Her tragic life showed that she was a pawn in her father’s ambitions. Due to her father’s will, she married Emperor Ping. Yet, when her father usurped the throne for himself, she very rarely defied him except on minor occasions. In the end, Empress Wang has been known in history for her famous last words and by choosing her own death rather than having her fate be chosen by the hands of her enemies.

Empress Wang (also formerly known as Empress Xiao Ping Wang Huangshou) was born around 9 B.C.E.[1] She was the daughter of Wang Mang and his wife, Lady Wang.[2] Her great-aunt was Grand Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun, who was the current regent to Emperor Ping.[3] The Grand Empress Dowager appointed Wang Mang as Commander-in-Chief to help Emperor Ping with his duties to the throne.[4]

Wang Mang was the unofficial regent of the Han dynasty. Still, Wang Mang hungered for more power and wanted to strengthen his rule by marrying his daughter to Emperor Ping.[5] He knew that Grand Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun would oppose the match, so he came up with a clever ploy.[6] In 4 C.E., at the age of thirteen, Wang was a candidate for the selection of palace women to Emperor Ping.[7] Wang Mang pretended to withdraw his daughter from the competition, claiming he believed his daughter to be an unsuitable candidate for Emperor Ping because of her humble background.[8] However, many petitions from scholars, commoners, and court officials were submitted to Grand Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun, asking her to appoint Wang Mang’s daughter as Empress to Emperor Ping.[9] Due to the overwhelming volume of petitions, Grand Empress Dowager Wang Zhengjun had no choice but to accept his daughter as Empress.[10]

In 4, C.E., Wang married Emperor Ping and became Empress. Shortly after his daughter’s investiture as Empress, Wang Mang was made Duke Anshan and was given the title of “Steward-Regulator of the State”.[11] This title was higher than Prince or Marquis.[12] In 5 C.E., Emperor Ping died. Wang Mang became regent to the new Emperor, Liu Ying. The new Emperor was the great-great-grandson of Emperor Xuan, and to the greatest advantage to Wang Mang, he was only a one year-old.[13]

In 9 C.E., Wang Mang deposed Liu Ying and made him Duke Ding’an.[14] Wang Mang usurped the throne and made himself Emperor.[15] He established his own dynasty called the Xin.[16] Emperor Wang Mang made his young widowed daughter Empress Dowager.[17]

However, Emperor Wang Mang did not want his daughter to remain a widow for the rest of his life.[18] He wanted her to remarry to suit his own personal interests.[19] Thus, he changed his daughter’s title from Empress Dowager Wang to “Illustrious Princess of the Imperial Clan.” [20] Emperor Wang Mang wanted Empress Wang to marry the son of Sun Jian, the Duke of Chengxing and who helped put Wang Mang on the throne.[21]

Empress Wang was said to be very obedient to her father.[22] She did not attend any court meetings because she often pleaded illness as an excuse.[23] However, Empress Wang refused to remarry because she was still mourning the loss of Emperor Ping, whom she deeply loved.[24] When her suitor paid a visit to her, Empress Wang pretended to be ill.[25] Yet, she had enough strength to order her suitor’s bodyguards to be whipped in the dungeons.[26] Empress Wang refused to get out of bed, and eventually, Emperor Wang Mang abandoned all his plans for his daughter’s remarriage.[27]

In 23 C.E., Wang Mang was overthrown by the armies of the Han dynasty.[28] Weiyang Palace, the imperial palace, burned.[29] Empress Wang realized that there was no hope in her situation.[30] She was filled with remorse for being a pawn in her father’s ambitions.[31] She said her famous last words, “How can I face the Han imperial family with a clear conscience?”[32] Immediately after she said those words, she threw herself into the fiery flames of the burning Weiyang Palace.[33]

The words and actions of Empress Wang give us a glimpse into her psyche.[34] She knew that what her father had done was wrong, but she rarely defied him.[35] On the few occasions that she did defy him by refusing to remarry and feigning illness shows that the Empress could have the potential to stand up to her father.[36] Because of her submissiveness to her father’s will, Empress Wang was filled with remorse and guilt at the end of her life.[37] Thus, Empress Wang’s tragic life has often been seen as a morality tale, for one should always have the courage to stand up for what one believes to be right and not be a passive, silent bystander.[38]

Sources:

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Mu, M. (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge.

Waldherr, K. (2008). Doomed Queens: Royal Women Who Met Bad Ends, From Cleopatra to Princess Di. NY: Bloomsbury Books.

[1] Mu, p. 201

[2] Mu, p. 201

[3] Mu, p. 201

[4] Mu, p. 201

[5] Waldherr, p. 49

[6] McMahon, p. 92

[7] Mu, p. 201

[8] McMahon, p. 92

[9] McMahon, p. 92

[10] McMahon, p. 92

[11] Mu, p. 201

[12] Mu, p. 201

[13] Mu, p. 201

[14] Mu, p. 201

[15] Mu, p. 201

[16] Mu, p. 201

[17] Mu, p. 201

[18] Mu, p. 201

[19] Mu, p. 201

[20] Mu, p. 201

[21] Mu, p. 201

[22] Mu, p. 201

[23] Waldherr, p. 49

[24] Waldherr, p. 49

[25] Mu, p. 201

[26] Mu, p. 201

[27] Mu, p. 201

[28] Mu, p. 202

[29] Mu, p. 202

[30] Waldherr, p. 49

[31] Mu, p. 202

[32] Mu, p. 202

[33] Waldherr, p. 49; Mu, p. 202

[34] Mu, p. 202

[35] Mu, p. 202

[36] Mu, p. 202

[37] Mu, p. 202

[38] Waldherr, p. 49

The post Empress Wang – The usurper’s daughter appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 1, 2022

Finding the grave of Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora

Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora of Leiningen died on 23 September 1872 in Villa Hohenlohe am Michaelsberg in Baden-Baden after a long sickbed. Queen Victoria had last visited her sister in March of that year when Victoria came to Baden-Baden. Victoria and Feodora said goodbye for the final time on 6 April 1872, and just one day later, Feodora wrote, “My beloved Victoria – the parting from you was very painful.1 It would be the last time the sisters would meet. Unfortunately, Feodora was already ill by then.

Following her death in September, a letter was found among Feodora’s papers to be given to Queen Victoria after Feodora’s death. It contained this passage, “I can never thank you enough for all you have done for me, for your great love and tender affection. These feelings cannot die; they must and will live on with my soul – till we meet again, never more to be separated – and you will not forget. Your own loving sister, Feodora.”2

Feodora left Villa Hohenlohe to Queen Victoria, who made a private visit there for three days in September 1873. She also visited Feodora’s grave and approved the final design for the monument created by Feodora’s son Victor. The angel on the tomb looks directly to the villa across the valley, although the villa no longer exists as Feodora would have known it.

Feodora’s grave still stands on the Hauptfriedhof of Baden-Baden and can be visited.3

Click to view slideshow.

The post Finding the grave of Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 30, 2022

Review: Elizabeth: A Portrait in Part(s)

It is no surprise that the Jubilee year would see at least one new documentary on the impressive 70-year reign of Queen Elizabeth II. Elizabeth: A Portrait in Part(s) was directed by Roger Michell, who died in September 2021 and is thus his last project.

The documentary unfolds under several headings, such as Mummy, Horribilis and In the Saddle and is not traditionally chronological. Instead, each part comes with an interesting mix of music and archival footage, making it more theatrical than a documentary. It’s fun and quirky, but it still manages to stay critical of the subject at hand.

We go from the preparations of a formal banquet to a cheering and relaxed Queen at the races. Some of the footage was new to me, which was a pleasant surprise indeed. There are, of course, mentions of the Windsor Castle fire and the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Also included is the more recent Prince Andrew interview. Yet, throughout all the ups and downs, the Queen remains at the centre of it all.

This modern documentary manages to capture the spirit of a steadfast woman, though its quirky nature may not appeal to everyone. Nevertheless, it’s certainly something different and is a welcome addition to what is already an impressive collection of Jubilee media.

Elizabeth: A Portrait in Part(s) is set for a theatrical release in the UK on 3 June, with no known release date yet for the US.

The post Review: Elizabeth: A Portrait in Part(s) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 29, 2022

Empress Feng Run – The Empress who cheated on the Emperor with a eunuch monk

Empress Feng Run was the second empress of Emperor Xiaowen. She has often been portrayed in a negative light. She has been depicted as a ruthless schemer who rid herself of her rivals, including her own sister. She even cheated on her husband with a eunuch monk and practised witchcraft to kill her husband. Yet, despite all her ruthless actions, Emperor Xiaowen continued to love her and protected her from being deposed.

Empress Feng Run was a great-granddaughter of Emperor Wentong of the short-lived Northern Yan dynasty.[1] Sometime after the Northern Wei defeated the Northern Yan Dynasty, Prince Feng Lang, Princess Feng Run’s grandfather, was executed.[2] Feng Run’s father, Prince Feng Xi, fled to the nomadic Qiang tribes.[3] In his exile, a slave woman named Chang bore him a daughter named Princess Feng Run.[4] Chang also gave birth to another daughter, but she died at a young age.[5]

Grand Empress Dowager Feng recalled Prince Feng Xi from exile. The King of the Qiang gave Prince Feng Xi a princess from his tribe to marry. This woman was Princess Boling of the Qiang tribe.[6] Princess Boling died shortly after giving birth to Feng Qing. After Princess Boling died, Prince Feng Xi married Chang, his former slave.[7]

Grand Empress Dowager Feng brought Princess Feng Run to the palace to be the future Empress of Emperor Xiaowen.[8] However, she fell ill and was placed in a Buddhist nunnery.[9] As soon as Princess Feng Run’s health had recovered, Emperor Xiaowen sent for Princess Feng Run to become his concubine.[10] She quickly became his favourite.[11] Yet, Consort Feng Run was ambitious and unhappy with her status. She was jealous of her half-sister, Empress Feng Qing’s status. Consort Feng Run slandered Empress Feng Qing.[12] She kept demanding her half-sister’s deposition.[13] At last, Emperor Xiaowen relented. In 496 C.E., Emperor Xiaowen deposed Empress Feng Qing and forced her to become a Buddhist nun.[14] In 497 C.E., Feng Run was installed as Empress.[15]

Empress Feng Run remained childless.[16] Lady Gao gave birth to the heir apparent named Yuan Ke. Shortly afterwards, Lady Gao died. Ancient chroniclers claimed that Empress Feng Run poisoned her.[17] It is unclear whether Empress Feng Run had a hand in Lady Gao’s death.[18] Later, when Yuan Ke took the throne in 499, he made Lady Gao the posthumous “Empress Dowager Wenzhao”.[19] Empress Feng Run was made the foster mother to the heir apparent, but they did not get along.[20]

Emperor Xiaowen went on military expeditions for years.[21] Thus, he rarely saw Empress Feng Run. Empress Feng Run had fallen in love with Gao Pusa, who was both a eunuch and a Buddhist monk.[22] The Emperor’s absence gave the opportunity for Empress Feng Run to indulge in her love affair with the eunuch monk.[23]

Empress Feng Run wished to increase her family’s status.[24] She wanted her younger brother to marry Emperor Xiaowen’s sister, Princess Pengcheng. Princess Pengcheng was so unwilling to marry the Empress’s brother that she told Emperor Xiaowen about Empress Feng Run’s passionate love affair with the eunuch monk.[25] Emperor Xiaowen refused to believe his sister’s accusation.[26] When Empress Feng Run learned that Princess Pengcheng had told her husband about her love affair, she was worried that she would be deposed like her half-sister. She and her mother, Princess Chang, practised witchcraft to kill the Emperor.[27] The witchcraft failed, and the news reached the Emperor’s ears. Even though there was evidence that Empress Feng Run and Princess Chang had practised witchcraft, Emperor Xiaowen refused to believe that his Empress had tried to kill him.[28]

In 499 C.E., Emperor Xiaowen laid dying on his deathbed. He ordered Empress Feng Run to commit suicide by poison but that she would receive a burial fit for an Empress.[29] This may have been seen as an act of love.[30] Emperor Xiaowen knew his brothers hated Empress Feng Run.[31] They made it clear that once he died, they would kill the Empress themselves. [32] Thus, Emperor Xiaowen probably thought that having her commit suicide by poison would be better than his brother’s methods of eliminating her. Empress Feng Run died of poison and was given a burial fit for an Empress. It is clear that Empress Feng Run was hated during and after her lifetime. Nevertheless, Emperor Xiaowen continued to love Empress Feng Run despite her cruel actions.

Sources:

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Tai, P. Y. & Ching-Chung, P. (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge.

[1] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[2] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[3] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[4] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[5] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[6] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[7] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[8] McMahon, p. 140

[9] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[10] McMahon, p. 140

[11] McMahon, p. 140

[12] McMahon, pp. 140-141

[13] McMahon, pp. 140-141

[14] McMahon, p. 141

[15] McMahon, p. 141

[16] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[17] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[18] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[19] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[20] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[21] McMahon, p. 141

[22] McMahon, p. 141

[23] McMahon, p. 141

[24] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[25] McMahon, p. 141

[26] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[27] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[28] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[29] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[30] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[31] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[32] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

The post Empress Feng Run – The Empress who cheated on the Emperor with a eunuch monk appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 28, 2022

Heidelberg Castle – The ruins of a magnificent castle

Once a grand royal residence overlooking the city of Heidelberg, Heidelberg Castle now lies mostly in ruins. Yet, it has retained its magnificence, and you only need to walk among the ruins to imagine what it must have been like.

The castle has links to several royal women. For example, Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate (Liselotte), later Duchess of Orléans, was born in the castle in 1652. Until 1658, she lived under the care of her aunt Sophia of the Palatinate, who then married Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. Elisabeth Charlotte later wrote, “I am not flattering enough. Flattery is a difficult art, and one that one does not learn on the Heidelberg hill. To be an adept in it, one must have been born in Prance or Italy.”1

Elisabeth Charlotte’s mother, Landgravine Charlotte of Hesse-Kassel, married Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine, at the castle in 1650, but it was an unhappy marriage. Despite this, she refused a divorce and lived in a wing of the castle. She eventually left in 1663 and only returned when her son succeeded his father in 1680. She died in the castle in 1686.

The Winter Queen, Elizabeth Stuart, lived at Heidelberg during her marriage to Frederick V, Elector Palatine and the Elizabeth Gate, built for her birthday in just one night, still stands. Two sons and her daughter Elisabeth were born at Heidelberg Castle. In 1619, the couple was briefly King and Queen of Bohemia and were afterwards exiled to the Netherlands.

Click to view slideshow.The castle ruins are now open to the public. You can reach it by taking the funicular railway, which also sells combination tickets for the castle itself.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe inside of some of the buildings can be visited, though, at the time of my visit, these tours were not being offered due to COVID-19 restrictions. Despite this, I really enjoyed my visit, and the different building styles are just amazing to see. There was also a little shop, which did not appear to sell anything in the way of information about the castle (books, for example). Souvenirs were also rather lacking, and they seemed to focus more on Christmas (I visited in December). Hopefully, this will be different during the actual tourist season as I was rather disappointed.

To plan your visit, go here.The post Heidelberg Castle – The ruins of a magnificent castle appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 26, 2022

Empress Feng Qing – The deposed Empress who was forced to become a Buddhist nun

Empress Feng Qing’s story is truly tragic. She was a woman who could not control her own fate. She was the first Empress of Emperor Xiaowen. However, she was supplanted by her own half-sister, Feng Run. Feng Run did not have any sisterly affection for Empress Feng Qing. Instead, Feng Run slandered her and demanded her half-sister’s deposition. Emperor Xiaowen, at last, gave way. He deposed Empress Feng Qing and forced her to become a Buddhist nun. Even though she had a tragic ending, Feng Qing proved to be a virtuous empress.

Empress Feng Qing was a great-granddaughter of Emperor Wentong of the short-lived Northern Yan dynasty.[1] Sometime after the Northern Wei defeated the Northern Yan dynasty, Princess Feng Qing’s grandfather, Prince Feng Lang, was executed.[2] Feng Qing’s father, Prince Feng Xi, fled to the nomadic Qiang tribes.[3] When Grand Empress Dowager Feng recalled Prince Feng Xi from exile, the King of the Qiang gave Prince Feng Xi a princess from his tribe to marry. This woman was Princess Boling of the Qiang tribe and Feng Qing’s mother.[4] Princess Boling died shortly after giving birth to Feng Qing. Feng Qing had an older half-sister named Princess Feng Run. Princess Feng Run was the daughter of Prince Feng Xi and a slave woman named Chang.[5] After Princess Boling died, Prince Feng Xi married Chang, his former slave.[6]

Grand Empress Dowager Feng brought her older half-sister Princess Feng Run to the palace to be the future Empress of Emperor Xiaowen[7]. However, she fell ill and was placed in a Buddhist nunnery.[8] Grand Empress Dowager Feng sent for Princess Feng Qing. Princess Feng Qing married Emperor Xiaowen and became his concubine.[9]

After Grand Empress Dowager Feng died, Emperor Xiaowen changed his last name from Tuoba to the Han-Chinese name Yuan.[10] He also moved his capital of Pingcheng to Luoyang.[11] He installed Feng Qing as his Empress in 493 C.E.[12] As Empress, Feng Qing managed the inner palace well.[13] She suggested for the Emperor to treat all his consorts equally instead of favouring only a few.[14] She also supported the Emperor in his policies and helped the harem transition easily into the new capital.[15]

Once Emperor Xiaowen’s new capital was established, Princess Feng Run had recovered from her illness, and Emperor Xiaowen ordered her to become his concubine.[16] As soon as Princess Feng Run arrived, she quickly became the Emperor’s favourite.[17] Emperor Xiaowen openly snubbed Empress Feng Qing and openly favoured Consort Feng Run. Empress Feng Qing did not receive any kindness from her arrogant half-sister. Consort Feng Run frequently slandered her. She kept on insisting to Emperor Xiaowen that he should depose Empress Feng Qing and make her Empress instead.[18] Emperor Xiaowen did as Consort Feng Run suggested. In 496 C.E., Emperor Xiaowen deposed Empress Feng Qing and forced her to become a Buddhist nun.[19] In 497 C.E., Feng Run was invested as Empress.[20]

When Prince Feng Xi died, the deposed Empress Feng Qing came out of the nunnery to attend the mourning ceremonies.[21] After the funeral, she went back to her nunnery, where she spent the rest of her life. Just like her birth, the date of her death remains unrecorded. Even though she spent most of her life in obscurity, ancient chroniclers have ensured that she was not forgotten. Many writers have been moved by Empress Feng Qing’s tragic story.[22] She has been praised as a paragon of virtue.

Sources:

McMahon, K. (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Tai, P. Y. & Ching-Chung, P. (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge.

[1] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[2] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[3] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[4] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[5] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[6] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[7] McMahon, p. 140

[8] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[9] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[10] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[11] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[12] McMahon, p. 140

[13] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[14] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[15] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 284

[16] McMahon, p. 140

[17] McMahon, p. 140

[18] McMahon, pp. 140-141

[19] McMahon, p. 141

[20] McMahon, p. 141

[21] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

[22] Tai & Ching-Chung, p. 285

The post Empress Feng Qing – The deposed Empress who was forced to become a Buddhist nun appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 24, 2022

Karlsruhe Palace – From royal palace to museum

Karlsruhe Palace began its life in 1715 upon the orders of Margrave Charles III William of Baden-Durlach. It was rebuilt in stone 50 years later and underwent some renovations in the years to come under the Grand Dukes of Baden. However, it ceased to be a royal residence with the end of the monarchy in 1918. During the Second World War, it suffered heavy damage from bombings, but it has been completely restored to its former glory, and it currently houses the Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe.

So while it is still a palace, only part of it is actually dedicated to the former royals. Much of the museum focuses on the entire history of the region. The downstairs area begins with the former glory of Grand Duchy.

Click to view slideshow.Unfortunately, due to the rebuilding, you won’t find any rooms as they were in the past. Victoria of Baden, later Queen of Sweden, was born at this palace and was raised here. Sophie of Sweden, Grand Duchess of Baden, gave birth to several children here and died in the palace on 6 July 1865. Amalie of Baden, later Princess of Fürstenberg, was born there to mother Louise Caroline of Hochberg, from an initially morganatic marriage to Charles Frederick, Grand Duke of Baden. These are just a few examples.

Among the several wings of the palace, you’ll find some more royal history scattered about.

Click to view slideshow.Overall, the museum is rather interesting, though a bit confusing with all the different wings. The gift shop even had some books about royal women. Find out more about their hours and admission prices here.

The post Karlsruhe Palace – From royal palace to museum appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 23, 2022

The Year of Empress Elisabeth – The wedding of Sisi and Franz Joseph

On 24 April 1854, at 7 o’clock in the evening, Elisabeth and Franz Joseph were married in the Augustinerkirche in Vienna.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksOver 15,000 candles lit the church as they were married, and the splendour was later described with the words, “All that the utmost in luxury, combined with the greatest of riches and truly imperial splendour, is able to offer, dazzles the eye here. In particular, in regard to the jewels, one can surely say that a sea of precious stones and pearls billowed past the marvelling eyes of the assembled crowd. Especially the diamonds seemed to multiply a thousandfold in the gold of the sumptuous illumination and made a magical impression by the wealth of their colour.”1

(screenshot/fair use)

(screenshot/fair use)Elisabeth wore a gown of white and silver, strewn with myrtle blossom and an opal and diamond crown. She was led up the aisle by her mother and her soon-to-be mother-in-law.

(public domain)

(public domain)

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe ceremony was performed by the Archbishop of Vienna with the assistance of more than 70 bishops and prelates. When the rings were exchanged, the first salvo was released from the roof of the church, followed by the thunder of the cannons. The wedding address, which was apparently rather long, earned the Archbishop the nickname “Cardinal Plauscher” (blabbermouth).2 After the religious rites, the ceremonial procession returned the bride and groom to the Hofburg, where they would hold an audience.

In the audience chamber, ambassadors and envoys were introduced to the new Empress. After this, they moved to the Hall of Mirrors, where the ladies of the diplomatic corps were waiting in full regalia to be introduced to Elisabeth. Then came the introductions to the Royal Household in the Hall of Ceremony. This is where Elisabeth panicked and fled the room in tears. She was able to pull herself together again, but when she returned, she was too timid to make conversation. However, protocol dictated that no one was allowed to speak unless when replying to questions. Countess Esterházy saved the day by asking the ladies to say a few words to the Empress.

Elisabeth then spotted her cousins Adelgunde and Hildegard of Bavaria and refused to let them kiss her hand and wished to give them a hug instead. However, the outraged expressions of the crowd told her she had committed a faux-pas, and she indignantly defended herself, “But they are cousins!”3 Archduchess Sophie reminded her of her new position and insisted on following the protocol. At the end of all the introductions came a gala banquet.

At the end of the gala banquet, the bride and groom were led to Elisabeth’s rooms. Archduchess Sophie wrote, “Ludovika and I led the young bride to her rooms. I left her with her mother and stayed in the small room next to the bedroom until she was in bed. Then I fetched my son and led him to his young wife, whom I saw once more, to wish her a good night. She hid her pretty face, surrounded by the masses of her beautiful hair, in her pillow, as a frightened bird hides in its nest.”4 Due to a lack of privacy, we know that the actual consummation did not take place until the third night.

The post The Year of Empress Elisabeth – The wedding of Sisi and Franz Joseph appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 22, 2022

Book News May 2022

Queen Victoria and The Romanovs: Sixty Years of Mutual Distrust

Paperback – 15 February 2022 (UK) & 15 May 2022 (US)

Despite their frequent visits to England, Queen Victoria never quite trusted the Romanovs. In her letters she referred to ‘horrid Russia’ and was adamant that she did not wish her granddaughters to marry into that barbaric country. ‘Russia I could not wish for any of you,’ she said. She distrusted Tsar Nicholas I but as a young woman she was bowled over by his son, the future Alexander II, although there could be no question of a marriage. Political questions loomed large and the Crimean War did nothing to improve relations. This distrust started with the story of the Queen’s ‘Aunt Julie’, Princess Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and her disastrous Russian marriage. Starting with this marital catastrophe, Romanov expert Coryne Hall traces sixty years of family feuding that include outright war, inter-marriages, assassination, and the Great Game in Afghanistan, when Alexander III called Victoria ‘a pampered, sentimental, selfish old woman’. In the fateful year of 1894, Victoria must come to terms with the fact that her granddaughter has become Nicholas II’s wife, the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Eventually, distrust of the German Kaiser brings Victoria and the Tsar closer together. Permission has kindly been granted by the Royal Archives at Windsor to use extracts from Queen Victoria’s journals to tell this fascinating story of family relations played out on the world stage.

The People’s Princess

Paperback – 31 March 2022 (UK) & 17 May 2022 (US)

The stunning new historical novel from the author of the bestselling Before the Crown. Perfect for fans of Gill Paul, Wendy Holden, Pam Jenoff and Jennifer Robson!

Buckingham Palace, 1981

Her engagement to Prince Charles is a dream come true for Lady Diana Spencer but marrying the heir to the throne is not all that it seems. Alone and bored in the palace, she resents the stuffy courtiers who are intent on instructing her about her new role as Princess of Wales…

But when she discovers a diary written in the 1800s by Princess Charlotte of Wales, a young woman born into a gilded cage so like herself, Diana is drawn into the story of Charlotte’s reckless love affairs and fraught relationship with her father, the Prince Regent.

As she reads the diary, Diana can see many parallels with her own life and future as Princess of Wales.

The story allows a behind-the-scenes glimpse of life in the palace, the tensions in Diana’s relationship with the royal family during the engagement, and the wedding itself.

Daughters of the North: Jean Gordon and Mary, Queen of Scots

Hardcover – 17 March 2022 (UK) & 17 May 2022 (US)

Mary, Queen of Scots’ marriage to the Earl of Bothwell is notorious. Less known is Bothwell’s first wife, Jean Gordon, who extricated herself from their marriage and survived the intrigue of the Queen’s court.

Daughters of the North reframes this turbulent period in history by focusing on Jean, who became Countess of Sutherland. Follow her from the intrigues of Mary’s court to the blood feuds and clan battles of the Far North of Scotland, from her place as the daughter of the ‘King of the North’ to her disastrous union with the infamous Earl of Bothwell – and her lasting legacy to the Earldom of Sutherland.

Philippa of Hainault: Mother of the English Nation

Paperback – 15 January 2022 (UK) & 15 May 2022 (US)

Philippa of Hainault: Mother of the English Nation is the first full-length biography of the queen at the centre of the some of the most dramatic events in English history. Philippa’s marriage to Edward III was arranged in order to provide ships and mercenaries for her mother-in-law to invade her father-in-law’s kingdom in 1326, yet it became one of the most successful royal marriages and endured for more than four decades. The chronicler Jean Froissart described her as, ‘The most gentle Queen, most liberal, and most courteous that ever was Queen in her days.’ Philippa stood by her husband’s side as he began a war against her uncle, Philip VI of France, and claimed his throne. She frequently accompanied him to France and Flanders during his early campaigns of the Hundred Years War. She also acted as regent in 1346 when Edward was away from his kingdom at the time of a Scottish invasion. She appeared on horseback to rally the English army to victory. Philippa became popular with the people due to her kindness and compassion. This popularity helped maintain peace in England throughout Edward’s reign. Her son, later known as the Black Prince ‒ the eldest of her thirteen children ‒ became one of the greatest warriors of the Middle Ages. Her extraordinary life did not escape tragedy: in 1348 three of her children died, almost certainly of the Black Death.

The Daughters of George III: Sisters and Princesses

Paperback – 31 May 2022 (US) & 30 March 2023 (UK)

In the dying years of the 18th century, the corridors of Windsor echoed to the footsteps of six princesses. They were Charlotte, Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary, Sophia, and Amelia, the daughters of King George III and Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Though more than fifteen years divided the births of the eldest sister from the youngest, these princesses all shared a longing for escape. Faced with their father’s illness and their mother’s dominance, for all but one a life away from the seclusion of the royal household seemed like an unobtainable dream.

The Times Queen Elizabeth II: Her 70 Year Reign

Hardcover – 15 May 2022 (US) & 14 October 2021 (UK)

Published to commemorate The Queen’s Platinum Jubilee this full color book is a detailed profile of Britain’s longest serving monarch. The story of a life dedicated to public service is told from her time as a young princess to a hugely respected head of state.

Tudor Roses: From Margaret Beaufort to Elizabeth I

Hardcover – 15 May 2022 (US) & 15 February 2022 (UK)

All too often, a dynasty is defined by its men, with the women depicted as shadowy figures whose value lies in the inheritance they brought, or the children they produced. Yet the Tudor dynasty is full of fascinating women, from Margaret Beaufort, who emerged triumphant after years of turmoil; Elizabeth of York’s steadying influence; Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, whose rivalry was played out against the backdrop of the Reformation; to Mary I and Elizabeth, England’s first reigning Queens. Many more women danced the Pavane under Henry VIII’s watchful eye or helped adjust Elizabeth’s ruff. These were strong, powerful women, whether that was behind the scenes or on the international stage. Their contribution took England from the medieval era into the modern. It is time for a new narrative of the Tudor women: one that prioritizes their experiences and their voices.

Pocket Diana Wisdom: Wise and Inspirational Words from the People’s Princess

Hardcover – 10 May 2022 (US) & 12 May 2022 (UK)

In Pocket Diana Wisdom, the Princess of Wales shares her pearls of wisdom on everything from love to humanitarian work to inspire hope and kindness in people all over the world. Full of inspirational quotes and wise words, this little book pays homage to the people’s princess.

Queen Elizabeth II: An Oral History

Hardcover – 3 May 2022 (US & UK)

This lavishly produced hardback with rarely seen color photos paints a full, detailed and sympathetic portrait of a life lived in service.

Featuring interviews from diverse sources from private staff at Buckingham Palace and family friends, to international figures like Nelson Mandela, it contains a broad spectrum of views on Queen Elizabeth II—her story and her personality and how her life has intersected and impacted others.

Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen (AmazonClassics Edition)

Kindle Edition – 3 May 2022 (US & UK)

Part memoir, part historical record, this intimate narrative by the first and only queen regnant of Hawaii offers a behind-the-scenes account of the kingdom’s annexation by the US and reckons with the emotional and political fallout of that event.

In this unusually personal document, Queen Liliʻuokalani paints a detailed picture of life in a royal family—something few such figures ever attempt. She shares important memories from her childhood and chronicles her life on the international stage, beginning with her momentous ascension to the throne and ending with her effective overthrow by American businessmen and politicians who had little interest in maintaining Hawaii’s autonomy.

Agnès Sorel and the French Monarchy: History, Gallantry, and National Identity (Gender and Power in the Premodern World)

Hardcover – 31 May 2022 (US & UK)

Agnès Sorel (1428–1450), beautiful favourite of Charles VII of France and first in the long genealogy of French royal mistresses, was mysteriously poisoned in the prime of life. Agnès, part of a network of royal “favourites,” is equally interesting for her political activity. And yet, no scholarly study in English of her exists. This study brings her story to an English-speaking audience, examining her in her historical context, that is, the factional struggle for power waged against Charles VII by the dauphin Louis and the king’s final routing of the English. It then traces Agnès’s afterlife, exploring her roles as founding mother of the tradition of the French royal mistress and foil for the less popular holders of the “office”; as erotic fantasy figure for nineteenth-century historians “re-inventing” the Middle Ages; and, most recently, as poignant victim for fans of the true crime genre.

Catherine the Great and the Culture of Celebrity in the Eighteenth Century (Cultures of Early Modern Europe)

Hardcover – 19 May 2022 (US) & 26 May 2022 (UK)

This book presents long neglected material evidence of the tsarina’s fantasy-inducing fame, examines the 1762 coup as the indispensable story that first constructed her distant public image, and explains how the themes of enlightenment, luxury consumption, clashing gender roles, and exotic Russia continued to attract non-elite fans and anti-fans during the middle decades of her reign. For the later years, the book considers the scrutiny inspired by the French Revolution and Catherine’s skewering in unsparing misogynist cartoons as they applied to visual representations, her achievements as ruler, the long-ago overthrow of her husband, and her gradually revealed list of lovers. Dawson reflects on Catherine II’s demise in 1796 and how this instigated a final burst of adoration, loathing, and ambivalence as new accounts of her life, both real and fictional, claimed to unwrap the final secrets of the first modern international female celebrity – even now the only woman in history widely known as ‘the Great’.

Mary I in Writing: Letters, Literature, and Representation (Queenship and Power)

Hardcover – 15 May 2022 (US & UK)

This book―along with its companion volume Writing Mary I: History, Historiography, and Fiction―centers on representations of Queen Mary I in writing, broadly construed, and the process of writing that queen into literature and other textual sources. It spans an equally wide chronological and geographical scope, accounting for the years prior to her accession in July 1553 through the centuries that followed her death in November 1558 and for her reach across England, and into Ireland, Spain, Italy, Russia, and Africa. Its intent is to foreground words and language―written, spoken, and acted out―and, by extension, to draw out matters of and conversations about rhetoric, imagery, methodology, source base, genre, narrative, form, and more. Taken together, these two volumes find in England’s first crowned queen regnant an incomparable opportunity to ask new questions and seek new answers that deepen our understanding of queenship, the early modern era, and modern popular culture.

Selected Letters, 1514-1543 (Volume 90) (The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe: The Toronto Series)

Paperback – 5 May 2022 (US & UK)

In recent years, there has been an upsurge of interest in Maria Salviati de’ Medici, specifically, in her role in Medici governance and her relationships with other members of the Medici court. Maria Salviati’s surviving correspondence documents a life spent close to the centers of Medici power in Florence and Rome, giving witness to its failures, resurrection, and eventual triumph. Presented here for the first time in English, this book is a representative sample of Maria’s surviving letters that document her remarkable life through a tumultuous period of Italian Renaissance history. While she earned the exasperation of some, she gained the respect of many more. Maria ended her life as an influential dowager, powerful intercessor for local Tuscans of all strata, and wise elder in Duke Cosimo I’s court. The first critical, analytical, biographical work on Maria Salviati de’ Medici’s life and letter-writing in English.

The Platinum Queen: Over 75 Speeches Given by Britain’s Longest-Reigning Monarch

Hardcover – 5 May 2022 (UK) & 1 July 2022 (US)

For the first time, all 70 of the Queen’s Christmas speeches are published together in full, along with six additional feature speeches made at significant points in her life.

The Queen: 101 Reasons to Celebrate Her Majesty – The Platinum Jubilee edition

Hardcover – 12 May 2022 (UK)

This book is a charming and witty paean to our longest-serving monarch; a collection of all the things that make Queen Elizabeth II a national treasure, from the profound impact she has had on 21st century politics, to her unshakeable sense of duty to her fabulous collection of headscarves.

With beautiful illustrations and humorous observations, The Queen:101 Reasons to Celebrate Her Majesty is a joyful celebration of a monarch who will go down in history as one of the greatest of all time.

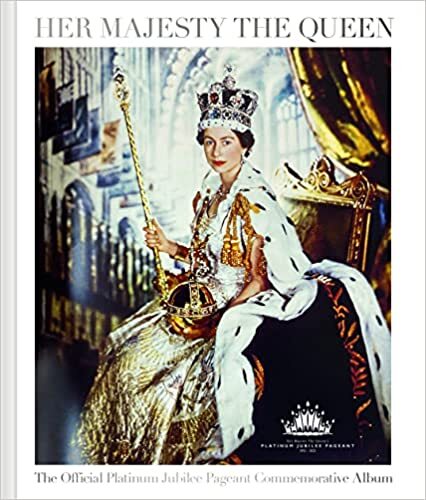

Her Majesty The Queen: The Official Platinum Jubilee Pageant Commemorative Album

Hardcover – 12 May 2022 (UK)

Accompanying this unique and joyous occasion, Her Majesty The Queen: The Official Platinum Jubilee Pageant Commemorative Album charts the trials and triumphs of The Queen’s 70-year reign and explores how Her Majesty has provided the country and Commonwealth with a lifetime of leadership, from her steadfast presence during the Second World War through to her current unifying influence at a time of political, economic and social turbulence.

The post Book News May 2022 appeared first on History of Royal Women.