Seth Godin's Blog, page 201

June 14, 2012

"I don't even know what I'm afraid of"

This is the fear that kills brands and b2b sales and individual creativity. It's the fear without a name, without a face, without false facts that can be shot down or arguments that can be reasoned with.

This is the amygdala firing, the lizard brain being triggered without rational explanation.

When we are wrestling against the elusive and resilient fear with no name, often the only choice is to live with it, to care enough about forward motion and practical progress that we can come embrace the inner trembling that won't give up.

In market after market paralyzed with fear, this trembling might be the very best sign that you're on to something.

June 13, 2012

Seven marketing sins

Impatient... great marketing takes time. Doing it wrong (and rushed) ten times costs much more and takes longer than doing it slowly, but right, over the same period of time.

Selfish... we have a choice, and if we sense that this is all about you, not us, our choice will be to go somewhere else.

Self-absorbed... you don't buy from you, others buy from you. They don't care about your business and your troubles nearly as much as you do.

Deceitful... see selfish, above. If you don't tell us the truth, it's probably because you're selfish. How urgent can your needs be that you would sacrifice your future to get something now?

Inconsistent... we're not paying that much attention, but when we do, it helps if you are similar to the voice we heard from last time.

Angry... at us? Why are you angry at us? It's not something we want to be part of, thanks.

Jealous... is someone doing better than you? Of course they are. There's always someone doing better than you. But if you let your jealousy change your products or your attitude or your story, we're going to leave.

Of course, they're not marketing sins, they're human failings.

Humility, empathy, generosity, patience and kindness, combined with the arrogance of the brilliant inventor, are a potent alternative.

June 12, 2012

Either, not both

Stand out or fit in.

Not all the time, and never at the same time, but it's always a choice.

Those that choose to fit in should expect to avoid criticism (and be ignored). Those that stand out should expect neither.

June 11, 2012

How to succeed

You don't need all of these, and some are mutually exclusive (while others are not). And most don't work, don't scale or can't be arranged:

Be very focused on your goal and work on it daily

Go to college with someone who makes it big and then hires you

Be born with significant and unique talent

Practice every day

Network your way to the top by inviting yourself from one lunch to another, trading favors as you go

Quietly do your job day in and day out until someone notices you and gives you the promotion you deserve

Do the emotional labor of working on things that others fear

Notice things, turn them into insights and then relentlessly turn those insights into projects that resonate

Hire a great PR firm and get a lot of publicity

Work the informational interview angle

Perform outrageous acts and say obnoxious things

Inherit

Redefine your version of success as: whatever I have right now

Flit from project to project until you alight on something that works out very quickly and well

Be the best-looking person in the room

Flirt

Tell stories that people care about and spread

Contribute more than is expected

Give credit to others

Take responsibility

Aggrandize, preferably self

Be a jerk and win through intimidation

Be a doormat and refuse to speak up or stand up

Never hesitate to share a kind word when it's deserved

Sue people

Treat every gig as an opportunity to create art

Cut corners

Focus on defeating the competition

When dealing with employees, act like Steve. It worked for him, apparently.

Persist, always surviving to ship something tomorrow

When in doubt, throw a tantrum

Have the ability to work harder and more directly than anyone else when the situation demands it

Don't rock the boat

Rock the boat

Don't rock the boat, baby

Resort to black hat tactics to get more than your share

Work to pay more taxes

Work to evade taxes

Find typos

June 10, 2012

Compared to magical

The easiest way to sell yourself short is to compare your work to the competition. To say that you are 5% cheaper or have one or two features that stand out--this is a formula for slightly better mediocrity.

The goal ought to be to compare yourself not to the best your peers or the competition has managed to get through a committee or down on paper, but to an unattainable, magical unicorn.

Compared to that, how are you doing?

June 9, 2012

Silencing the bell doesn't put out the fire

Many big organizations have full-time employees who scan the social media, looking for people with a complaint. They swoop in and grease the squeaky wheel, solving the problem of the person who spoke up.

The theory is that these loud complainers are a problem, and the easiest solution is to give them something to make them happy.

Of course, that doesn't do anything for the 95% of the population that has the very same problem but isn't speaking up, right?

When Jeff Jarvis blogged about Dell Hell, he hurt the company very badly. Mollifying Jeff (and those like him) did the company no good in the long run, though, because they didn't deal with the underlying cause, they merely gave the loud ones an excuse to be quiet.

The purpose of the bell is to point to a fire somewhere else. Worry about that instead.

June 8, 2012

It's not all in your head

But part of it is.

We spend an enormous amount of time trying to get the world to align with the vision we have for what will make us happy or successful.

Whatever "it" is, figuring out how to deal with the noise in your head is probably faster and cheaper than changing the outside world. Not easier, though, merely important.

June 7, 2012

The unforgiving arithmetic of the funnel

One percent.

That's how many you get if you're lucky. One percent of the subscribers to the Times read an article and take action. One percent of the visitors to a website click a button to find out more. One percent of the people in a classroom are sparked by an idea and go do something about it.

And then!

And then, of that 1%, perhaps 1% go ahead and take more action, or recruit others, or write a book or volunteer. One percent of one percent.

No wonder advertisers have to run so many ads. Most of us ignore most of them. No wonder it's so hard to convert a digital browsing audience into a real world paying one--most people are in too much of a hurry to read and think and pause and then do.

The common mistake is to reflexively come to the conclusion that the only option is to make more noise, to put more attention into the top of the funnel. The thinking goes that if a big audience is getting you mediocre results, a huge audience is the answer. Alas, a huge audience is more difficult than the alternatives.

A few ways to deal with the funnel:

Acknowledge that it's there. Don't assume that a big audience is going to easily convert to action.

Work to measure your losses. Figure out where in the process you're losing interest and clicks or the other behaviors you seek.

If you can, remove steps. Each step costs you dearly.

Treat different people differently. If you alter the funnel to maximize interest by the wandering masses, you may very well miss the chance to convert the focused few.

June 6, 2012

Forbidden to care

The rigid, measured, top down structure of big company customer service makes it almost impossible for the rep to care about you when you call.

One new trend is that if you have a complicated problem or a bit of attitude in your voice, the call center rep will 'accidentally' disconnect you. You're going to hurt his numbers. His yield will go down and it's just not worth it. Let someone else take the call...

When organizations take away all flexibility and power from their frontline employees, they're depriving the people with the highest leverage from doing the most important thing: caring.

June 5, 2012

The Dip, revisited, plus audio bonus

Five years ago, I published a little book (little even by my standards) called The Dip.

I did a tour, built a small blog and shared what I could about it. It was a very risky book—certainly not for everyone.

Much to the surprise of some at my publishing house, it sold a ton of copies, entirely due to word of mouth.

The book makes a lot of people uncomfortable. Instead of giving a clear, actionable, step-by-step approach to guaranteed success, The Dip points out where we often get stuck, and leaves it to the reader to take the (difficult) steps necessary to move ahead.

It also talked about the short head (in contrast to Chris Anderson's not yet written Long Tail). There's a short head in every micro market, just waiting for someone to fill it.

Just yesterday, the rule of the Dip was demonstrated by Microsoft's overdue cancellation of the Zune, something that should have happened years ago.

As the web becomes every more relentless in separating the average from the exceptional, the simple idea this book uncovers (being the best in the world at your little niche) becomes ever more important.

This week, I got a bunch of mail about the book, and it prompted me to remind you that you might want to (re)read it. Jared wrote (italics mine):

It literally speaks to my heart and convinces me of changes I need to make in my life. I need to quit a bunch of stuff, and try to be the best.

I have a confession to make. This is my second time reading this book, and the first time I thought it was pretty basic and kind of stupid. But I decided to read it again (4 years later) and it is exactly what I need at this point in my life. I absolutely love it.

...

Anyways, I just want to say thank you for pushing through the dip.

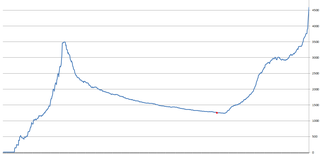

And then, the next day, this graph showed up from Dan in Norway:

The red dot indicates the day he read the book. I'm not sure what this measures, but it looks good.

I hope the book resonates for you as well. Because it's not a brand new book, you can find used copies for less than $3. And a freebie...listen to the first 10% on audio:

Seth Godin's Blog

- Seth Godin's profile

- 6535 followers