Catherine Crier's Blog, page 4

October 4, 2012

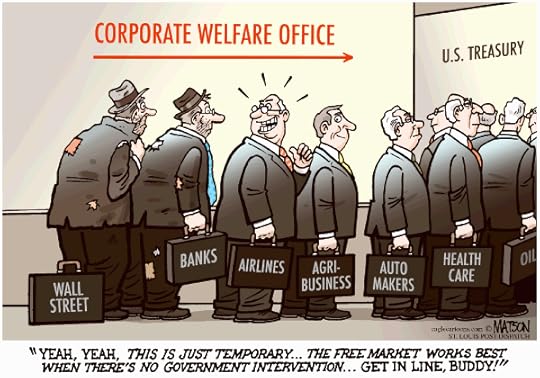

Public Money Continues to Supplement the Building of Private Corporate Infrastructure

Our nation is still experiencing the after-effects of major economic crisis, and yet public money continues to supplement the building of private corporate infrastructure. Time and time again, our legislators and government officials have proven that they’re willing to put the interests of the public aside in order to appease big business by lowering tax rates, offering more tax breaks, and increasing corporate subsidies.

These government subsidies do not encourage economic growth as much as productive taxpayers do, and as a result, everything from Social Security to unemployment and welfare rolls is affected. As you’ll see in the following article, when it comes to competitive business privileges—tax breaks, subsidies, overt political power—individuals and small businesses might as well fugetaboutit.

From The Huffington Post

Welfare Spending Nearly Half What U.S. Forked Out In Corporate Subsidies In 2006: Study

Welfare queens may actually look more like giant corporations.

The government spent about $59 billion to pay for traditional social welfare programs like food stamps and housing assistance in 2006, while Uncle Sam doled out $92 billion in assistance to corporations during the same year, according to an analysis from Think By Numbers, a progressive blog. That means that big, and in many cases profitable, corporations got nearly double the money from the government that needy individuals got.

The analysis finds renewed significance because of the debate raging on the campaign trail and in Congress over government subsidies to businesses and individuals. A video of Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney slamming 47 percent of Americans for not paying income taxes and feeling entitled to government assistance leaked last week to widespread criticism.

If Romney is elected, policies based on that philosophy may be put into action. His running mate Paul Ryan, for example, has proposed slashing food stamp spending.

At the same time, Romney’s supporters have been asking for more government subsidies for big business. Harold Hamm, Romney’s top energy adviser, asked lawmakers to keep tax breaks for oil and gas companies in place during a hearing earlier this month. Companies tied to Romney’s image have also benefitted from government help; Bain & Co. reportedly received a bailout in the early 1990s.

President Obama has proposed lowering the top corporate tax rate to 28 percent in exchange for a reduction in potential loopholes, according to The New York Times. Many corporations already pay well below the current 35 percent rate by using a variety of loopholes.

Not everyone is in favor of corporate subsidies though, even people who have received corporate subsidies. Charles Koch, the CEO of Koch Industries, argued in a Wall Street Journal op-ed earlier this month that crony capitalism is a “destructive force”for business and government. Koch’s company, which also set up a SuperPAC that’s raised more than $2.5 million this election cycle, has benefitted from this so-called “crony capitalism” in the form of subsidies for the oil and gas industry as well as huge government contracts.

October 3, 2012

Modern “Conservatives” Are Quick to Impede Progress Without Offering a Different Course

The Republican Party I knew growing up was brimming with “progressive” visionaries who valued national investment in science technology and infrastructure—building, innovating, and investing, publicly and privately, in America’s future. Now, modern “conservatives” are quick to put the brakes on progress without offering a different course.

If they wish to revitalize the Republican Party, conservatives must be willing to strike a balance between free-market ideologies and traditional conservative principles. Balancing these interests does not mean confiscating and redistributing wealth or subsidizing people’s lives, but inequalities must be addressed. Your thoughts?

From The New York Times

The Conservative Mind

By DAVID BROOKSWhen I joined the staff of National Review as a lowly associate in 1984, the magazine, and the conservative movement itself, was a fusion of two different mentalities.

On the one side, there were the economic conservatives. These were people that anybody following contemporary Republican politics would be familiar with. They spent a lot of time worrying about the way government intrudes upon economic liberty. They upheld freedom as their highest political value. They admired risk-takers. They worried that excessive government would create a sclerotic nation with a dependent populace.

But there was another sort of conservative, who would be less familiar now. This was the traditional conservative, intellectual heir to Edmund Burke, Russell Kirk, Clinton Rossiter and Catholic social teaching. This sort of conservative didn’t see society as a battleground between government and the private sector. Instead, the traditionalist wanted to preserve a society that functioned as a harmonious ecosystem, in which the different layers were nestled upon each other: individual, family, company, neighborhood, religion, city government and national government.

Because they were conservative, they tended to believe that power should be devolved down to the lower levels of this chain. They believed that people should lead disciplined, orderly lives, but doubted that individuals have the ability to do this alone, unaided by social custom and by God. So they were intensely interested in creating the sort of social, economic and political order that would encourage people to work hard, finish school and postpone childbearing until marriage.

Recently the blogger Rod Dreher linked to Kirk’s essay, “Ten Conservative Principles,” which gives the flavor of this brand of traditional conservatism. This kind of conservative cherishes custom, believing that the individual is foolish but the species is wise. It is usually best to be guided by precedent.

This conservative believes in prudence on the grounds that society is complicated and it’s generally best to reform it steadily but cautiously. Providence moves slowly but the devil hurries.

The two conservative tendencies lived in tension. But together they embodied a truth that was put into words by the child psychologist John Bowlby, that life is best organized as a series of daring ventures from a secure base.

The economic conservatives were in charge of the daring ventures that produced economic growth. The traditionalists were in charge of establishing the secure base — a society in which families are intact, self-discipline is the rule, children are secure and government provides a subtle hand.

Ronald Reagan embodied both sides of this fusion, and George W. Bush tried to recreate it with his compassionate conservatism. But that effort was doomed because in the ensuing years, conservatism changed.

In the polarized political conflict with liberalism, shrinking government has become the organizing conservative principle. Economic conservatives have the money and the institutions. They have taken control. Traditional conservatism has gone into eclipse. These days, speakers at Republican gatherings almost always use the language of market conservatism — getting government off our backs, enhancing economic freedom. Even Mitt Romney, who subscribes to a faith that knows a lot about social capital, relies exclusively on the language of market conservatism.

It’s not so much that today’s Republican politicians reject traditional, one-nation conservatism. They don’t even know it exists. There are few people on the conservative side who’d be willing to raise taxes on the affluent to fund mobility programs for the working class. There are very few willing to use government to actively intervene in chaotic neighborhoods, even when 40 percent of American kids are born out of wedlock. There are very few Republicans who protest against a House Republican budget proposal that cuts domestic discretionary spending to absurdly low levels.

The results have been unfortunate. Since they no longer speak in the language of social order, Republicans have very little to offer the less educated half of this country. Republicans have very little to say to Hispanic voters, who often come from cultures that place high value on communal solidarity.

Republicans repeat formulas — government support equals dependency — that make sense according to free-market ideology, but oversimplify the real world. Republicans like Romney often rely on an economic language that seems corporate and alien to people who do not define themselves in economic terms. No wonder Romney has trouble relating.

Some people blame bad campaign managers for Romney’s underperforming campaign, but the problem is deeper. Conservatism has lost the balance between economic and traditional conservatism. The Republican Party has abandoned half of its intellectual ammunition. It appeals to people as potential business owners, but not as parents, neighbors and citizens.

A version of this op-ed appeared in print on September 25, 2012, on page A23 of the New York edition with the headline: The Conservative Mind.

October 2, 2012

96 Percent of Americans Have Relied on Social Welfare Programs

In a 2008 national survey conducted at Cornell, 96 percent of Americans reported needing the assistance of federal social welfare programs at some point in their life. However, many government officials, especially Republican leaders, regularly insist upon deep cuts to services for most citizens while simultaneously defending tax breaks, subsidies, and overt political power for transnational corporations.

In its preamble, the Founders stated explicitly that our Constitution was established to promote the general welfare. Americans recognize the difference between ideological rhetoric and realistic solutions, and what they’re seeking is honest leadership that puts the welfare of citizens and our system of government above all else. Would you agree?

From The New York Times

We Are the 96 Percent

By SUZANNE METTLER and JOHN SIDES

WHEN Mitt Romney told the guests at a fund-raiser in Florida in May that America is divided between people who pay no income taxes and depend on government and pretty much everyone else, he missed the deeper truth. It is not just that most of the 47 percent Mr. Romney talked about do pay payroll taxes and that many of them have paid income taxes in the past. The reality he glossed over is that nearly all Americans have used government social policies at some point in their lives. The beneficiaries include the rich and the poor, Democrats and Republicans. Almost everyone is both a maker and a taker.

We have unique data from a 2008 national survey by the Cornell Survey Research Institute that asked Americans whether they had ever taken advantage of any of 21 social policies provided by the federal government, from student loans to Medicare. These policies do not include government activity that benefits everyone — national defense, the interstate highway system, food safety regulations — but only tangible benefits that accrue to specific households.

The survey asked about people’s policy usage throughout their lives, not just at a moment in time, and it included questions about social policies embedded in the tax code, which are usually overlooked.

What the data reveal is striking: nearly all Americans — 96 percent — have relied on the federal government to assist them. Young adults, who are not yet eligible for many policies, account for most of the remaining 4 percent.

On average, people reported that they had used five social policies at some point in their lives. An individual typically had received two direct social benefits in the form of checks, goods or services paid for by government, like Social Security or unemployment insurance. Most had also benefited from three policies in which government’s role was “submerged,” meaning that it was channeled through the tax code or private organizations, like the homemortgage-interest deduction and the tax-free status of the employer contribution to employees’ health insurance. The design of these policies camouflages the fact that they are social benefits, too, just like the direct benefits that help Americans pay for housing, health care, retirement and college.

The use of government social policies cuts across partisan divides. Some policies were used more often by members of one party or the other. Republicans were more likely to have used the G.I. Bill and Social Security retirement and survivors’ benefits, while more Democrats had taken advantage of Medicaid and unemployment insurance. Overall, 82 percent of Democrats and 64 percent of Republicans acknowledged receipt of at least one direct social benefit. More Republicans (92 percent) than Democrats (86 percent) had taken advantage of submerged policies. Once we take both types of policies into account, the seeming distinction between makers and takers vanishes: 97 percent of Republicans and 98 percent of Democrats report that they have used at least one government social policy.

The majority of individuals from households at every income level have used at least one direct social policy. Low-income people have used more of the direct policies than have the affluent: the average household with income under $10,000 per year used four of them, compared to only one by the households at $150,000 and above. But the proportions were reversed in the case of the submerged policies: wealthy families had typically used three of them, and the poor just one.

There were also few partisan differences in how long individuals had benefited. Among policies used by similar percentages of Democrats and Republicans, like the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit and tax credits for college tuition, members of both parties received the benefits for the same average amount of time. The same was true for policies that benefited one group of partisans more than the other. For example, although the mortgage-interest deduction was claimed by more Republicans and the earned-income tax credit by more Democrats, both claimed the benefits for two to five years on average. Similarly, Republicans who relied on the G.I. Bill did so for about as long as did Democrats who claimed unemployment insurance benefits.

Where Americans actually differ is in how they think about government’s role in their lives. A major driving factor here is ideology: conservatives were less likely than liberals to respond affirmatively when asked if they had ever used a “government social program,” even when both subsequently acknowledged using the same number of specific policies.

These ideological differences were on display at the party conventions. When Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey noted that his father, who “grew up in poverty,” had used the G.I. Bill to become the first in his family to graduate from college, it was in the context of a speech criticizing our “need to be coddled by big government.” By contrast, Michelle Obama credited student loans with making her and her husband’s college educations possible and then argued that “when you’ve worked hard, and done well, and walked through that doorway of opportunity, you do not slam it shut behind you.”

Throughout our lives, almost all of us help sustain government social policies through our tax dollars and, at some point, almost all of us directly benefit from these policies. Because ideology influences how we view our own and others’ use of government, Mr. Romney’s remarks may resonate with those who think of themselves as “producers” rather than “moochers” — to use Ayn Rand’s distinction. But this distinction fails to capture the way Americans really experience government. Instead of dividing us, our experiences as both makers and takers ought to bind us in a community of shared sacrifice and mutual support.

Suzanne Mettler is a professor of government at Cornell and John Sides is an associate professor of political science at George Washington University.

September 25, 2012

Ayn Rand’s Radical Defense of Economic Darwinism

Ayn Rand, the self-proclaimed radical and author of Atlas Shrugged was the ultimate purist, advocating uncontrolled, unregulated capitalism. She perverted Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” into her “virtue of selfishness” and defended an ugly dog-eat-dog economic Darwinism: The masses were servile and insignificant, government was invasive and usually malevolent.

Absolute objectivism, along with the rest of Rand’s arguments, may sway teens—a time when renegade individualism stirs the blood—but time and experience validates the social/political principles envisioned by Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Adam Smith.

September 24, 2012

Banks Should Be Banks, Not Investment Houses or Gambling Casinos

In response to unregulated financial malfeasance and the Crash of ’29, The Banking Reform Act of 1933 imposed rules to ensure banks were banks, not investment houses or gambling casinos. When the legislation was introduced, the American Bankers Association protested, saying the bill was “unsound, unscientific, unjust, and dangerous.”

Our current crisis is due in no small part to the weakening of these provisions in the 1980s and the repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999. When you hear banks and their political cronies screaming about regulations today, just remember, we’ve heard it all before. They were wrong in ’33 and they’re wrong now.

From Bloomberg

FDIC’s Hoenig Says Banks May Revisit Pre-2008 Risky Behavior

By Jesse Hamilton

If big U.S. banks are not forced to sever their investment arms from traditional banking, they will return to behavior that led to the 2008 credit crisis, said Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. board member Thomas Hoenig.

“The behavior and practices leading to this crisis will soon reemerge and these highly complex, more vulnerable firms will have an even more devastating effect on the economy,” Hoenig said in remarks yesterday at the Exchequer Club in Washington. “Activities leading to the crisis continue today — and continue to be subsidized — well after the lessons should have been learned.”

Regulators should reinstate a separation between commercial banking and brokerages, a kind of “modern version” of the Glass-Steagall Act to separate commercial banking from brokerage operations, Hoenig has argued since before joining the FDIC in April. The public safety net should not protect the banking industry’s trading risks, according to the former Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City president.

Hoenig said major banks have “misled the markets regarding interest rates” and that “firms using FDIC-insured funds continue to make directional bets on asset values and global events.”

He said the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act and its so-called Volcker rule to ban banks from proprietary trading was insufficient and that the government safety net will still cover swaps trading and market making, “much of which could become veiled prop- trading.”

Big Banks

The big banks won’t “come along willingly” but should be forced to, Hoenig said.

“It is alarming that CEOs of some financial firms fail to grasp why they are trusted so little nor appreciate the reputational damage they caused their industry,” he said.

Last week, Hoenig said capital rules revised by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision should be replaced by a simpler leverage ratio. Basel’s U.S. implementation should be delayed, he said, and risk should instead be reduced with leverage ratio requirements.

Asked yesterday if tighter leverage rules and his proposal to split up complex banking operations could drive business into a so-called shadow banking system, he said his ideas would instead create a system in which capital demands would be clearer and the market would be more aware of its responsibilities.

“Yes, firms would fail, and yes, there will be disruptions from that, but it would not bring the entire world down,” Hoenig said.

Banks Should Be Banks, Not Investment Houses or Gambling Casinos.

In response to unregulated financial malfeasance and the Crash of ’29, The Banking Reform Act of 1933 imposed rules to ensure banks were banks, not investment houses or gambling casinos. When the legislation was introduced, the American Bankers Association protested, saying the bill was “unsound, unscientific, unjust, and dangerous.”

Our current crisis is due in no small part to the weakening of these provisions in the 1980s and the repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999. When you hear banks and their political cronies screaming about regulations today, just remember, we’ve heard it all before. They were wrong in ’33 and they’re wrong now.

From Bloomberg

FDIC’s Hoenig Says Banks May Revisit Pre-2008 Risky Behavior

By Jesse HamiltonIf big U.S. banks are not forced to sever their investment arms from traditional banking, they will return to behavior that led to the 2008 credit crisis, said Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. board member Thomas Hoenig.

“The behavior and practices leading to this crisis will soon reemerge and these highly complex, more vulnerable firms will have an even more devastating effect on the economy,” Hoenig said in remarks yesterday at the Exchequer Club in Washington. “Activities leading to the crisis continue today — and continue to be subsidized — well after the lessons should have been learned.”

Regulators should reinstate a separation between commercial banking and brokerages, a kind of “modern version” of the Glass-Steagall Act to separate commercial banking from brokerage operations, Hoenig has argued since before joining the FDIC in April. The public safety net should not protect the banking industry’s trading risks, according to the former Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City president.

Hoenig said major banks have “misled the markets regarding interest rates” and that “firms using FDIC-insured funds continue to make directional bets on asset values and global events.”

He said the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act and its so-called Volcker rule to ban banks from proprietary trading was insufficient and that the government safety net will still cover swaps trading and market making, “much of which could become veiled prop- trading.”

Big BanksThe big banks won’t “come along willingly” but should be forced to, Hoenig said.

“It is alarming that CEOs of some financial firms fail to grasp why they are trusted so little nor appreciate the reputational damage they caused their industry,” he said.

Last week, Hoenig said capital rules revised by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision should be replaced by a simpler leverage ratio. Basel’s U.S. implementation should be delayed, he said, and risk should instead be reduced with leverage ratio requirements.

Asked yesterday if tighter leverage rules and his proposal to split up complex banking operations could drive business into a so-called shadow banking system, he said his ideas would instead create a system in which capital demands would be clearer and the market would be more aware of its responsibilities.

“Yes, firms would fail, and yes, there will be disruptions from that, but it would not bring the entire world down,” Hoenig said.

September 20, 2012

Tax Cuts Do Not Increase Overall Revenues or Spur Domestic Business Investment and Job Growth

Cut taxes on the rich, so the argument goes, and this money will be reinvested at home. For those of you who have read Patriot Acts, we’ve been over this numerous times, but let me restate an empirical fact: Tax cuts for the wealthy do not increase overall revenues or spur domestic business investment and job growth.

A new longitudinal study compiles data from the last 65-years to find why tax cuts in and of themselves have never led to economic growth. In the past, the rich may have reinvested about a third of their tax savings in the US, but now, most of it goes into savings, personal spending, or overseas investments.

From The Huffington Post

Tax Cuts For The Rich Linked To Income Inequality, Not Economic Growth, Study Finds

By Bonnie Kavoussi

A new study by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service has found that over the past 65 years, tax cuts for the rich have not led to economic growth and instead are linked to greater income inequality in the United States.

The study found that cutting taxes for the rich does not increase saving, investment, or productivity growth. “The top tax rates appear to have little or no relation to the size of the economic pie,” the study said.

Two graphs show the lack of connection between tax rates for the rich and economic growth:

The authors noted that top-tier tax rates could have an effect on “how the economic pie is sliced.” The study noted that in 1945, when the richest families had to pay a marginal tax rate of more than 90 percent, the top 0.1 percent of U.S. families accumulated 4.2 percent of all income gains. In 2007, in contrast, when the top marginal tax rate was 35 percent (which it still is), the top 0.1 percent of U.S. families captured 12.3 percent of all income gains.

Two graphs from the study show a clear connection between higher taxes for the rich and less income inequality:

Those findings are inconvenient for the Romney campaign. In a continuation of trickle-down economic theory, the Republican presidential nominee has argued that cutting taxes for the rich would “stimulate entrepreneurship, job creation, and investment,” thus “breathing life into the present anemic recovery.”

Romney has said he wants to extend all of the Bush tax cuts, while President Obama wants to extend those tax cuts only on the first $250,000 of taxable income. Romney also wants to slash marginal tax rates and taxes on investment income, as well as eliminate the estate tax — all of which would disproportionately benefit the rich.

A recent study by Owen Zidar, a PhD student in Economics at the University of California at Berkeley, also found that tax cuts for the rich are not correlated with economic growth. But Zidar did find that tax cuts for the bottom 90 percent of income earners can stimulate economic growth and job creation.

(Hat tip: the New York Times’ David Leonhardt.)

September 16, 2012

Polling Suggest 66% of Americans Want Increased Spending on Public Transportation

Major investment in our national infrastructure is essential for economic growth at home and abroad. Polling conducted by the NRDC suggests that 66% of Americans want increased government spending on transportation and are willing to pay for it by way of increased sales tax or tolls.

Despite incontrovertible evidence that trickle-down economics is a sham, Republican legislators insist on tax cut extensions (or even more cuts) for the wealthiest Americans but refuse to invest in 21st-century transportation/infrastructure. Why is this? Your thoughts!

From The Hill

Enviro poll: 66 percent support more public transportation

By Keith Laing

Sixty-six percent of Americans want Congress to spend more money on public transportation, according a poll commissioned by a prominent environmental group.

The New York-based Natural Resources Defense Council said on Wednesday that its survey of 800 U.S. residents showed more Americans support increased public transportation construction than building more roads and highways.

“Americans hate traffic and love transit,” said Peter Lehner, NRDC’s executive director. “Investing in public transportation eases congestion, but for too long most federal funding has limited people’s choices, leaving them sitting in traffic.”

The NRDC survey found 59 percent of Americans believe the current U.S. public transportation system is “outdated, unreliable and inefficient.” The poll found 55 percent of its respondents said they would prefer to drive their cars less, but 74 percent believed they did not have any other option for mobility.

The poll found 58 percent said they would like to use public transportation more, but said it was not convenient to their work schedules or home locations.

The survey also found that a majority of Americans think that states spend about 16 percent of their transportation budget on public transit, compared to an average the NRDC said was closer to 6.5 percent.

Public transportation advocates like the Amalgamated Transit Union for transit workers said Wednesday that the NRDC poll validates their support for increased funding for railways and bus systems.

“Transit ridership in the U.S. is at an all-time high in decades and even more people would use it if they could,” ATU President Larry Hanley said in a statement. “Many believe Americans are in love with their cars, but most are frustrated with the lack of options for adequate, reliable public transit service.”

Hanley said the NRDC poll “clearly shows that taxpayers are willing to put their money where their mouth is — backing increased spending to make better public transportation a reality.

“Legislators should take note that public transit is not only a wise investment in our economy, but also a winning political position for people regardless of their party affiliation,” he said.

Lawmakers in the House briefly tried to eliminate a dedicated funding source for public transit systems in the recently approved $105 billion transportation measure. Supporters argued that the bill included more one-time funding for public transit than a traditional 80-20 percent split in federal gas tax revenue has provided.

But public transit advocates countered that removing the dedicated funding source would leave funding for railways and bus systems at the whims of future lawmakers, and the provision was removed from the final version of the transportation bill.

The full NRDC transportation poll can be read here:.

<![if !IE]><![endif]>

September 15, 2012

Vast Discrepancies Between Defense and State Department Funding

Diplomacy is a critical arm of our national security, yet there are more people in our military marching bands than in the State Department’s Foreign Service. In light of Tuesday’s tragic events in Benghazi, isn’t it about time we address the vast discrepancies between the annual budgets for the Defense Department ($614B) and the State Department ($51.6B)?

Our national security policies affect every aspect of our society—culturally, politically, and economically. Americans will always rally to defend this great nation, but a true patriot never fears a serious debate about the methods we use to accomplish this vital mission.

From Salon.com

How Congress left our embassies exposed

One reason our embassies are unable to protect themselves? Congress has been slashing their funding for years

BY JORDAN MICHAEL SMITHYemeni protestors climb the gate of the U.S. Embassy during a protest about a film ridiculing Islam’s Prophet Muhammad, in Sanaa, Yemen, Thursday, Sept. 13, 2012. (Credit: AP/Hani Mohammed)

Responding to mob attacks on a U.S. embassy and consulate in Egypt and Libya, Sens. John McCain, Joe Lieberman and Lindsey Graham said the following: “[W]e now look to the Libyan government to ensure that the perpetrators are swiftly brought to justice, and that U.S. diplomats are protected.” Well, if the senators want to better protect American diplomats, they will have to convince their colleagues. The Benghazi consulate where Ambassador Christopher Stevens was murdered had no Marines surrounding it, no bulletproof glass and no reinforced doors. Libyan security officials were partly in charge of securing the building.

Among the worst trends in U.S. foreign-policy making in recent decades is the decline of the State Department and the corresponding rise of the Defense Department. State is responsible for American diplomacy — the hard work of negotiating and maintaining relations with other countries; Defense (formerly the Department of War, a more honest designation) looks after war-making and protecting national security. Few things reflect America’s skewed foreign-policy priorities more than the funding discrepancies between the two departments. Consider the numbers:

In 1950, State had 7,710 diplomats abroad. In 2001, it actually had fewer — just 7,158. During that time the U.S. population approximately doubled.

As of 2010, the Pentagon admitted to having 190,000 troops and 909 military facilities in 46 countries and territories.

As of the fall of 2011, the U.S. had 1,300 civilian workers versus 100,000 military personnel in Afghanistan.

The State Department’s funding request for 2013 was $51.6 billion, $300 million less than 2012, because, it said, “this is a time of fiscal retraint.”

The Pentagon’s 2012 budget? $614 billion. Mitt Romney promises to increase defense spending dramatically.As Stephen Glain puts it in his wonderful and disturbing 2010 book “State vs. Defense,” “the Pentagon has all but eclipsed the State Department at the center of U.S. foreign policy.” It wasn’t always like this. With a few notable exceptions, during the first years of the Cold War, presidents relied far more on their State Department heads for advice than their Defense Department counterparts. Giants like George Marshall, Dean Acheson and John Foster Dulles had more control in the Truman and Eisenhower administrations over foreign-policy making than anyone else in the country, with the president excepted. It was assumed that their focus on grand strategy and knowledge of international affairs gave them more expertise in national security than the Defense Department secretaries, who were military men and might see the world more narrowly.

That balance began to change in the Kennedy administration. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had far more influence over Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson than did Secretary of State Dean Rusk. The switch reflected corresponding changes in U.S. foreign-policy emphasis from diplomacy to militarism. Since then, with a few important exceptions, Defense secretaries have strongly overpowered their State Department equivalents. At the very least, they have had a much greater role in American endeavors overseas, simply because they have far greater resources and power. Washington Post reporter Dana Priest explained it in her book “The Mission”: “The military simply filled a vacuum left by an indecisive White House, an atrophied State Department, and a distracted Congress … long before September 11, the U.S. government had grown dependent on its military to carry out its foreign affairs.”

Secretaries of State have had to beg for crumbs from Congress, which sees diplomacy as an easy thing to cut back — who lobbies for more money for diplomats? Military contractors have all the money. In addition, no president is criticized for gutting State, while taking even a nail file to Defense’s obese budget elicits slurs from the opposing party. Condi Rice demonstrated this problem. In 2000, as Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush’s foreign policy advisor, she said that it wasn’t the job of Defense to perform civilian duties. “We don’t need to have the 82nd Airborne escorting kids to kindergarten,” she quipped. By 2008, she was saying, “I still think that’s true, but somebody’s got to do it. And what we are learning is that the weakness of civilian institutions to do the business of state-building is one of the true lacuna, one of the true holes in our national capacity.” Indeed it is. But the big loser has been American diplomacy. Defense has so much money that it has essentially taken over both functions, as well as many others.

What does all this have to do with the diplomats killed in the Middle East on Tuesday? Well, embassies and consulates can’t be expected to have strong security apparatuses without any funding. They don’t have nearly enough staff members, let alone enough financial support for guards and protection. Who is going to control a mob of hundreds storming a U.S. embassy: an intern? Embassies are left exposed and often powerless in foreign countries, forced to defer to military officials on bases where they do not even belong.

The United States had virtually an entire city inside Iraq in the 2000s — 10 square kilometers that even the Chinese military couldn’t penetrate if it tried. The thing was as protected as any site in the history of the world, with concrete blast walls, T-Walls and barbed-wire fences. It couldn’t be entered except at checkpoints, all of which were controlled by Coalition troops.

American diplomats and civilian workers do not come close to competing with that. They are underfunded, underappreciated and mostly unknown to the American public. The tragedies on Tuesday in Cairo and Benghazi are symbolic of the State Department’s weakness in U.S. foreign policy. Too bad there is little hope of reversing the balance any time soon.

Jordan Michael Smith writes about U.S. foreign policy for Salon. He has written for the New York Times, Boston Globe and Washington Post. MORE JORDAN MICHAEL SMITH.

From Time.com

Did the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi Not Have Enough Security?

TIME speaks to the Libyan politician who had breakfast with U.S. Ambassador Chris Stevens on the day of the American’s death

By VIVIENNE WALT

A tomato-and-onion omelette, washed down with hot coffee: that was the last breakfast of U.S. Ambassador Chris Stevens’ life. And although the scene in the U.S. consulate’s canteen in Benghazi on Tuesday morning looked serene, under the surface there were signs of potential trouble, according to the Libyan politician who had breakfast with Stevens the morning before the ambassador and three other Americans died in a violent assault by armed Islamic militants. “I told him the security was not enough,” Fathi Baja, a political-science professor and one of the leaders of Libya’s rebel government during last year’s revolution, told TIME on Thursday. “I said, ‘Chris, this is a U.S. consulate. You have to add to the number of people, bring Americans here to guard it because the Libyans are not trained.”

Stevens, says Baja, listened attentively — but it was too late. On Tuesday night, armed Islamic militants laid siege to the consulate, firing rockets and grenades into the main building and the annex, pinning the staff and its security detail inside the blazing complex; U.S. officials told reporters on Wednesday they believed it took Libyan security guards about four hours to regain control of the main building. In the chaos, Stevens was separated in the dark from his colleagues, and hours later was transported by Libyans to a Benghazi hospital, where he died, alone, apparently of asphyxiation from the smoke.

U.S. officials told reporters on Wednesday that the Benghazi consulate had “a robust American security presence, including a strong component of regional security officers.” And indeed, one of the four Americans killed was former Navy SEAL Glen Doherty, who was “on security detail” and “protecting the ambassador,” his sister Katie Quigly told the Boston Globe. Also killed was an information-management officer, Sean Smith. The fourth American who died has not yet been identified. Yet Baja describes a very different picture from his visit on Tuesday morning, even remarking at how relaxed the scene was when he returned to the consulate building a short while after leaving Stevens, in order to collect the mobile phone he had accidentally left behind. “The consulate was very calm, with video [surveillance] cameras outside,” Baja says. “But inside there were only four security guards, all Libyans — four! — and with only Kalashnikovs on their backs. I said, ‘Chris, this is the most powerful country in the world. Other countries all have more guards than the U.S.,’” he says, naming as two examples Jordan and Morocco.

With the compound now an evacuated, smoldering ruin, Baja, who befriended Stevens in Benghazi during last year’s seven-month civil war, and in recent weeks had shared long Ramadan dinners with him, says he felt stricken not only by the loss but also by the sense that perhaps the tragedy could have been averted, had there been tighter security on the ground, and — more especially — had Libya’s nascent government cracked down against armed militia groups. Bristling with weaponry, much of it from Muammar Gaddafi’s huge abandoned arsenals, groups of former fighters have been permitted to act as local security forces in towns across Libya during the postwar upheaval in order to fill the security vacuum, despite the scant loyalty among many of them to the new democracy. “Up to now, there has been cover from the government for these extremist people,” Baja says, adding that he and Stevens had discussed for months the urgent threats from armed militia. “[Government officials] still pay them salaries, and I think this is disgusting.”

President Obama vowed on Wednesday to help track down the attackers. U.S. officials suspect the attack was a planned operation, rather than the result of a demonstration that got out of control. In an opinion piece on CNN.com on Thursday, Noman Benotman, a former leader of the militant Libyan Islamic Fighting Group who now runs the Quilliam Foundation, an anti-extremist organization in London, said he believed the attack had been the work of 20 militants. He told CNN that he believed a militant group called the Omar Abdul Rahman Brigades could have coordinated the attack, perhaps to avenge the killing of Abu Yahya al-Libi, a Libyan al-Qaeda leader, who died in a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan last June; the group also claimed responsibility for the attack last May against the International Red Cross in Benghazi.

In the scramble to figure out what went so calamitously wrong, U.S. officials deployed 50 Marines to Tripoli from a base in Spain, as members of an elite antiterrorism force called FAST, according to the Associated Press, citing unnamed U.S. officials. In addition, two American warships have been stationed off the Libyan coast.

Ironically, Benghazi had ostensibly held a special bond, as well as a debt of gratitude, to the U.S. and other Western countries — something highlighted in the bitter comments by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on Wednesday, when she expressed dismay that the attack occurred in a city the U.S. helped to save. French and American military jets pounded Gaddafi’s forces outside the city in March last year, saving Benghazi from the threat of mass slaughter.

The deep fondness for the U.S. is indeed felt in Benghazi, according to Baja, who was head of the political-affairs committee for Libya’s National Transitional Council until the elected government was installed last month. Stevens and Baja had met on Tuesday morning primarily to plan the American Cultural Center’s official opening, which was scheduled for Wednesday evening. “There was going to be a big ceremony,” Baja says. “There was going to be English classes. It was a very nice place.”

Recalling what he told Stevens over their omelettes, Baja says, “I told him, people admire the U.S. style of life, but that there were extremists, and we have to work in a cooperative way to put an end to these people,” adding that he had advocated pushing Libyan officials to crack down on armed militia. “He agreed with that. He knew this, he knew the names of the militia I told him, and their background.” Now that knowledge — some of it gone with Stevens’ disastrous death — could become key details in the grim investigation.

The Vast Discrepancies Between Defense and State Department Funding

Diplomacy is a critical arm of our national security, yet there are more people in our military marching bands than in the State Department’s Foreign Service. In light of Tuesday’s tragic events in Benghazi, isn’t it about time we address the vast discrepancies between the annual budgets for the Defense Department ($614B) and the State Department ($51.6B)?

Our national security policies affect every aspect of our society—culturally, politically, and economically. Americans will always rally to defend this great nation, but a true patriot never fears a serious debate about the methods we use to accomplish this vital mission.

From Salon.com

How Congress left our embassies exposed

One reason our embassies are unable to protect themselves? Congress has been slashing their funding for years

BY JORDAN MICHAEL SMITHYemeni protestors climb the gate of the U.S. Embassy during a protest about a film ridiculing Islam’s Prophet Muhammad, in Sanaa, Yemen, Thursday, Sept. 13, 2012. (Credit: AP/Hani Mohammed)

Responding to mob attacks on a U.S. embassy and consulate in Egypt and Libya, Sens. John McCain, Joe Lieberman and Lindsey Graham said the following: “[W]e now look to the Libyan government to ensure that the perpetrators are swiftly brought to justice, and that U.S. diplomats are protected.” Well, if the senators want to better protect American diplomats, they will have to convince their colleagues. The Benghazi consulate where Ambassador Christopher Stevens was murdered had no Marines surrounding it, no bulletproof glass and no reinforced doors. Libyan security officials were partly in charge of securing the building.

Among the worst trends in U.S. foreign-policy making in recent decades is the decline of the State Department and the corresponding rise of the Defense Department. State is responsible for American diplomacy — the hard work of negotiating and maintaining relations with other countries; Defense (formerly the Department of War, a more honest designation) looks after war-making and protecting national security. Few things reflect America’s skewed foreign-policy priorities more than the funding discrepancies between the two departments. Consider the numbers:

In 1950, State had 7,710 diplomats abroad. In 2001, it actually had fewer — just 7,158. During that time the U.S. population approximately doubled.

As of 2010, the Pentagon admitted to having 190,000 troops and 909 military facilities in 46 countries and territories.

As of the fall of 2011, the U.S. had 1,300 civilian workers versus 100,000 military personnel in Afghanistan.

The State Department’s funding request for 2013 was $51.6 billion, $300 million less than 2012, because, it said, “this is a time of fiscal retraint.”

The Pentagon’s 2012 budget? $614 billion. Mitt Romney promises to increase defense spending dramatically.As Stephen Glain puts it in his wonderful and disturbing 2010 book “State vs. Defense,” “the Pentagon has all but eclipsed the State Department at the center of U.S. foreign policy.” It wasn’t always like this. With a few notable exceptions, during the first years of the Cold War, presidents relied far more on their State Department heads for advice than their Defense Department counterparts. Giants like George Marshall, Dean Acheson and John Foster Dulles had more control in the Truman and Eisenhower administrations over foreign-policy making than anyone else in the country, with the president excepted. It was assumed that their focus on grand strategy and knowledge of international affairs gave them more expertise in national security than the Defense Department secretaries, who were military men and might see the world more narrowly.

That balance began to change in the Kennedy administration. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had far more influence over Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson than did Secretary of State Dean Rusk. The switch reflected corresponding changes in U.S. foreign-policy emphasis from diplomacy to militarism. Since then, with a few important exceptions, Defense secretaries have strongly overpowered their State Department equivalents. At the very least, they have had a much greater role in American endeavors overseas, simply because they have far greater resources and power. Washington Post reporter Dana Priest explained it in her book “The Mission”: “The military simply filled a vacuum left by an indecisive White House, an atrophied State Department, and a distracted Congress … long before September 11, the U.S. government had grown dependent on its military to carry out its foreign affairs.”

Secretaries of State have had to beg for crumbs from Congress, which sees diplomacy as an easy thing to cut back — who lobbies for more money for diplomats? Military contractors have all the money. In addition, no president is criticized for gutting State, while taking even a nail file to Defense’s obese budget elicits slurs from the opposing party. Condi Rice demonstrated this problem. In 2000, as Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush’s foreign policy advisor, she said that it wasn’t the job of Defense to perform civilian duties. “We don’t need to have the 82nd Airborne escorting kids to kindergarten,” she quipped. By 2008, she was saying, “I still think that’s true, but somebody’s got to do it. And what we are learning is that the weakness of civilian institutions to do the business of state-building is one of the true lacuna, one of the true holes in our national capacity.” Indeed it is. But the big loser has been American diplomacy. Defense has so much money that it has essentially taken over both functions, as well as many others.

What does all this have to do with the diplomats killed in the Middle East on Tuesday? Well, embassies and consulates can’t be expected to have strong security apparatuses without any funding. They don’t have nearly enough staff members, let alone enough financial support for guards and protection. Who is going to control a mob of hundreds storming a U.S. embassy: an intern? Embassies are left exposed and often powerless in foreign countries, forced to defer to military officials on bases where they do not even belong.

The United States had virtually an entire city inside Iraq in the 2000s — 10 square kilometers that even the Chinese military couldn’t penetrate if it tried. The thing was as protected as any site in the history of the world, with concrete blast walls, T-Walls and barbed-wire fences. It couldn’t be entered except at checkpoints, all of which were controlled by Coalition troops.

American diplomats and civilian workers do not come close to competing with that. They are underfunded, underappreciated and mostly unknown to the American public. The tragedies on Tuesday in Cairo and Benghazi are symbolic of the State Department’s weakness in U.S. foreign policy. Too bad there is little hope of reversing the balance any time soon.

Jordan Michael Smith writes about U.S. foreign policy for Salon. He has written for the New York Times, Boston Globe and Washington Post. MORE JORDAN MICHAEL SMITH.

From Time.com

Did the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi Not Have Enough Security?

TIME speaks to the Libyan politician who had breakfast with U.S. Ambassador Chris Stevens on the day of the American’s death

By VIVIENNE WALT

A tomato-and-onion omelette, washed down with hot coffee: that was the last breakfast of U.S. Ambassador Chris Stevens’ life. And although the scene in the U.S. consulate’s canteen in Benghazi on Tuesday morning looked serene, under the surface there were signs of potential trouble, according to the Libyan politician who had breakfast with Stevens the morning before the ambassador and three other Americans died in a violent assault by armed Islamic militants. “I told him the security was not enough,” Fathi Baja, a political-science professor and one of the leaders of Libya’s rebel government during last year’s revolution, told TIME on Thursday. “I said, ‘Chris, this is a U.S. consulate. You have to add to the number of people, bring Americans here to guard it because the Libyans are not trained.”

Stevens, says Baja, listened attentively — but it was too late. On Tuesday night, armed Islamic militants laid siege to the consulate, firing rockets and grenades into the main building and the annex, pinning the staff and its security detail inside the blazing complex; U.S. officials told reporters on Wednesday they believed it took Libyan security guards about four hours to regain control of the main building. In the chaos, Stevens was separated in the dark from his colleagues, and hours later was transported by Libyans to a Benghazi hospital, where he died, alone, apparently of asphyxiation from the smoke.

U.S. officials told reporters on Wednesday that the Benghazi consulate had “a robust American security presence, including a strong component of regional security officers.” And indeed, one of the four Americans killed was former Navy SEAL Glen Doherty, who was “on security detail” and “protecting the ambassador,” his sister Katie Quigly told the Boston Globe. Also killed was an information-management officer, Sean Smith. The fourth American who died has not yet been identified. Yet Baja describes a very different picture from his visit on Tuesday morning, even remarking at how relaxed the scene was when he returned to the consulate building a short while after leaving Stevens, in order to collect the mobile phone he had accidentally left behind. “The consulate was very calm, with video [surveillance] cameras outside,” Baja says. “But inside there were only four security guards, all Libyans — four! — and with only Kalashnikovs on their backs. I said, ‘Chris, this is the most powerful country in the world. Other countries all have more guards than the U.S.,’” he says, naming as two examples Jordan and Morocco.

With the compound now an evacuated, smoldering ruin, Baja, who befriended Stevens in Benghazi during last year’s seven-month civil war, and in recent weeks had shared long Ramadan dinners with him, says he felt stricken not only by the loss but also by the sense that perhaps the tragedy could have been averted, had there been tighter security on the ground, and — more especially — had Libya’s nascent government cracked down against armed militia groups. Bristling with weaponry, much of it from Muammar Gaddafi’s huge abandoned arsenals, groups of former fighters have been permitted to act as local security forces in towns across Libya during the postwar upheaval in order to fill the security vacuum, despite the scant loyalty among many of them to the new democracy. “Up to now, there has been cover from the government for these extremist people,” Baja says, adding that he and Stevens had discussed for months the urgent threats from armed militia. “[Government officials] still pay them salaries, and I think this is disgusting.”

President Obama vowed on Wednesday to help track down the attackers. U.S. officials suspect the attack was a planned operation, rather than the result of a demonstration that got out of control. In an opinion piece on CNN.com on Thursday, Noman Benotman, a former leader of the militant Libyan Islamic Fighting Group who now runs the Quilliam Foundation, an anti-extremist organization in London, said he believed the attack had been the work of 20 militants. He told CNN that he believed a militant group called the Omar Abdul Rahman Brigades could have coordinated the attack, perhaps to avenge the killing of Abu Yahya al-Libi, a Libyan al-Qaeda leader, who died in a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan last June; the group also claimed responsibility for the attack last May against the International Red Cross in Benghazi.

In the scramble to figure out what went so calamitously wrong, U.S. officials deployed 50 Marines to Tripoli from a base in Spain, as members of an elite antiterrorism force called FAST, according to the Associated Press, citing unnamed U.S. officials. In addition, two American warships have been stationed off the Libyan coast.

Ironically, Benghazi had ostensibly held a special bond, as well as a debt of gratitude, to the U.S. and other Western countries — something highlighted in the bitter comments by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on Wednesday, when she expressed dismay that the attack occurred in a city the U.S. helped to save. French and American military jets pounded Gaddafi’s forces outside the city in March last year, saving Benghazi from the threat of mass slaughter.

The deep fondness for the U.S. is indeed felt in Benghazi, according to Baja, who was head of the political-affairs committee for Libya’s National Transitional Council until the elected government was installed last month. Stevens and Baja had met on Tuesday morning primarily to plan the American Cultural Center’s official opening, which was scheduled for Wednesday evening. “There was going to be a big ceremony,” Baja says. “There was going to be English classes. It was a very nice place.”

Recalling what he told Stevens over their omelettes, Baja says, “I told him, people admire the U.S. style of life, but that there were extremists, and we have to work in a cooperative way to put an end to these people,” adding that he had advocated pushing Libyan officials to crack down on armed militia. “He agreed with that. He knew this, he knew the names of the militia I told him, and their background.” Now that knowledge — some of it gone with Stevens’ disastrous death — could become key details in the grim investigation.