Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 55

September 4, 2014

Write About Things You Know – Not About Yourself

English teachers and other instructors of creative writing classes are in the habit of telling aspiring young writers to “write about things you know.” There’s a good reason for this. If they didn’t make this seemingly obvious suggestion, they would have a lot of students coming to them for ideas or failing to write a single sentence because they “didn’t know what to write about.”

The problem with this practical piece of advice is that, while useful in the classroom, it is too often transferred out of that context. “Writing about what you know” is a way to get started. It is a way to practice and exercise, to develop skill and style. It is not – repeat not - the finished product.

A finished product is a piece of writing that you wish to share with a wider public than your teacher, classmates, close friends and relatives. And this is where it is important to make a very important transition.

If you are writing for public consumption – i.e. if you plan to publish in a magazine, on the internet or to publish a book – then you should not confuse “writing about things you know” with writing about yourself. Yes, if you’re already a celebrity, people might be interested in you, but, if not, the chances are that no one who doesn’t already know you is going to be interested in reading about you. Do you go out and buy autobiographies of people who have never done anything exceptional or heroic? Do you read books about people who have not achieved fame or fortune? And if you do, how many have you bought? Have you read a dozen, a score, a-hundred-thousand? Believe me, the market for autobiographies by John and Jane Doe is very limited indeed. In fact, it is limited to about the number of copies John and Jane Doe are prepared to buy themselves to try and give away.

“Writing about what you know” does not, however, necessarily mean writing about yourself. It can mean writing about a familiar environment, or abstracting from personal experience to more universal experiences. In this sense, “writing about what you know” can indeed be useful component in a finished product. The point is simply that the finished product is unlikely to use this knowledge one-to-one as in autobiography, but as part of a larger, more universally appealing story.

In short, while it is perfectly legitimate to try to learn writing skills without a particular message in mind, no one should aspire to be a writer unless he/she has something to say. In fact, no one should aspire “to be a writer” at all because being a writer is meaningless; the message is everything. Writing is a means to an end, not an end in itself. In the same way, writing “about what you know” should be a means to an end: either a way to learn writing skills or a way to deliver a more profound and universal message in a convincing manner.

The problem with this practical piece of advice is that, while useful in the classroom, it is too often transferred out of that context. “Writing about what you know” is a way to get started. It is a way to practice and exercise, to develop skill and style. It is not – repeat not - the finished product.

A finished product is a piece of writing that you wish to share with a wider public than your teacher, classmates, close friends and relatives. And this is where it is important to make a very important transition.

If you are writing for public consumption – i.e. if you plan to publish in a magazine, on the internet or to publish a book – then you should not confuse “writing about things you know” with writing about yourself. Yes, if you’re already a celebrity, people might be interested in you, but, if not, the chances are that no one who doesn’t already know you is going to be interested in reading about you. Do you go out and buy autobiographies of people who have never done anything exceptional or heroic? Do you read books about people who have not achieved fame or fortune? And if you do, how many have you bought? Have you read a dozen, a score, a-hundred-thousand? Believe me, the market for autobiographies by John and Jane Doe is very limited indeed. In fact, it is limited to about the number of copies John and Jane Doe are prepared to buy themselves to try and give away.

“Writing about what you know” does not, however, necessarily mean writing about yourself. It can mean writing about a familiar environment, or abstracting from personal experience to more universal experiences. In this sense, “writing about what you know” can indeed be useful component in a finished product. The point is simply that the finished product is unlikely to use this knowledge one-to-one as in autobiography, but as part of a larger, more universally appealing story.

In short, while it is perfectly legitimate to try to learn writing skills without a particular message in mind, no one should aspire to be a writer unless he/she has something to say. In fact, no one should aspire “to be a writer” at all because being a writer is meaningless; the message is everything. Writing is a means to an end, not an end in itself. In the same way, writing “about what you know” should be a means to an end: either a way to learn writing skills or a way to deliver a more profound and universal message in a convincing manner.

Published on September 04, 2014 15:30

August 28, 2014

Wash-out?

Excerpts from Chasing the Wind (Kindle edition: Where Eagles Never Flew)

"You alright, Ernst?" Christian asked with apparent concern as he poured wine for himself. "The MO said you had a concussion and no other serious injuries, but..." Christian looked at him intently. "What's bothering you?"

Ernst couldn't take the scrutiny. The tension was just too much, or the contrast between the inner tension and the warm, cosy environment was too much. Ernst wasn't someone who could pretend anyway. He burst out, "Christian I'm a wash-out, aren't I?"

"Whatever for? You did a great job putting your Emil down without breaking anything."

"But -- I mean -- that I had to crash at all. I mean...." Too late, Ernst realized that Christian didn't know about the oxygen and that he'd been lost. But they would find out as soon as they investigated. Ernst's head was killing him. He dropped it into his hands and just held it.

"Come on. What's eating you?" Christian urged in a friendly tone.

"My oxygen."

"What about it?" Christian asked confused.

"There wasn't anything wrong with it -- I'd just forgotten to plug it in." Ernst was so ashamed, he didn't dare meet Christian's eyes as he admitted this.

Christian just laughed. Ernst stared at him. "Hell. Who hasn't done that once or twice?"

"But I -- I panicked! I half-rolled and dived instead of staying below the Staffel. And I didn't realize what was wrong 'till I was back on the deck and, and...."

Christian leaned his elbows on the table and looked Ernst straight in the eye. "If you aren't getting any oxygen, you can't think properly. That's all there is to it. It's normal. don't let it get to you. What's important is that you plugged in and tried to catch up with us."

"Yes -- but I couldn't find you."

"Of course not. The weather closed in too fast and the sweep was scratched."

Ernst stared at Christian, hardly daring to believe what he was being told. Christian acted as if he wasn't to blame for what happened. He tried to explain. "I got lost Christian. I didn't know where I was. I kept following the coast, but I couldnt' find anything familiar -- not even Le Harve. I looked and looked, but I couldn't find any familiar landmark. It -- it was just luck that I landed so near the ZG base."

"How long have you been with us, Ernst? Ten days?"

Ernst nodded.

"And how many of those days have we flown? --not even half." Christian answered his own question. "So you've flown in France all of four times, right? and rarely the same route? And in better weather. Any of us might have lost our way in this muck."

Ernst stared at him, almost afraid to believe him, but Christian really seemed to mean it.

"Cheer up, Ernst!" Christian urged with a smile. "If I have to spend the evening with you rather than Gabrielle, than at least try to make it a pleasant evening, all right?"

"Gabrielle? Is that your French girl friend?" Ernst ventured timidly. "Didn't the CO order you to stop seeing her?"

"So what? We've signed a truce with France. Half the Gestapo has French girl friends nowadays! What do they expect us to do? Live like monks? That's not healthy!" Christian delcared with conviction.

Ernst snickered in embarrassment. He'd never had a girl friend, and he was far too inhibited to go to whores. The very thought made him feel dirty. He didn't want it like that. He wanted a nice girl, who was there just for him. She didn't have to be beautiful, just kind and sympathetic and nice. He found himself gazing at his wine, wishing, while Christian continued his commentary.

Christian was telling him about meeting Gabrielle, and somehow he made it all sound very amusing. In fact, Christian soon had Ernst laughing. He forgot about his headach, and getting lost, and crashing. And when he remembered again, it didn't seem so bad.

Excerpt 2: New Assignment

Axel shook out a cigarette, and Christian took it thankfully. Axel gave him a light. As he straightened from bending over the match, the pilot's eyes fell on the two girls, still hovering just within earshot. He smiled at them at once, and Klaudia's alarm signals went off. She took a step backwarks, but it was too late.

"Has the Luftwaffe come up with the delightful idea of training Helferinnen to service aircraft?"

Axel turned back from the waist, saw what Christian had seen, and with a somewhat annoyed frown signalled the girls forward as he explained. "No. They're both in Communications, but Rosa and I met at StG2. After I'd written back about how nice it was here, she got it into her head to follow me over."

Axel had his hand around Rosa's elbow as he introduced her. "Rosa Welkerling." Christian clicked his heels and bowed his head, smiling, but his eyes had already shifted to Klaudia. "Klaudia von Richthofen," Axel duly introduced her, adding for the benefit of the girls, "Christian Freiherr von Feldburg."

Again Christian clicked his heels and bowed to Klaudia. Klaudia was so distressed to find herself attracted to him when she had hardly recovered from what Jako had done to her, that she was immensely relieved when the fat pilot emerged beside them. He distracted the handsome baron, who turned on him to declare triumphantly, "I told you not to worry about me."

"You barely made it," Ernst pointed out.

"Perfect planning, as the CO would say," Christian assured him, flinging an arm over his wingman's shoulders.

"The CO won't say anything of the kind," Ernst retorted with a sour expression.

"He would, if he'd done it," Christian reasoned, and they all laughed a bit more loudly than the joke justified. Christian and Ernst started to turn away, but Christian remembered to politely nod to the girls. Then the pilots were gone and Axel turned to the Helferinnen rather sharply. "We've got work to do. See you later."

"As you like," Rosa answered, miffed, as the started to turn away. Then she stopped and called out, "Axel?"

"Now what?"

"You never looked that nervous when Pashinger was late."

"Arschinger was an asshole."

"And this baron's not?"

"Feldburg? No, he's all right."

....

By about ten pm, Klaudia was falling asleep upright. It had been an eventful day, and she was no longer used to wine with dinner. She stood, hiding a yawn behind her hand, and announced she was turning in.

"I'll come too," Rosa agreed.

They said good night to the other girls and left their little mess, crossing the darkened games room and making for the main stairs. But as they reached the stairs sweeping up from the reception area, they could hear music and singing coming up from the Officer's Bar on the left. "Listen!" Rosa said with delight. "That's Veronica, der Lenz ist da!" When Klaudia looked blankly at her, she added, "You know, by the Comedian Harmonists! Surely you know the Comedian Harmonists?" Rosa might be a good National Socialist, but nothing could ruin her delight in the songs of the Berlin quintet. She tiptoed toward the stairs that led down into the rustic bar with its flagstone floor and beamed ceiling a half-floor below.

Someone was playing a piano very well, and several men were indeed singing in harmony. There was also the stamping of feet and clapping of hands to heard. Rosa tiptoed down four or five steps until, by bending, she could see into the bar itself. In a line with their arms around each other's shoulders, four of the pilots were dancing to the music as they sang.

They had their tunics completely unbuttoned, their ties loosened, and the pilots on the ends -- the fat pilot Ernst Geuke and a man she didn't recognize -- were having some trouple keeping up with the steps. In the centre, very much the motor of the little act, was -- who else? -- Christian Freiherr v. Feldburg....

Klaudia tried to picture Jako doing some kind of can-can with his tunic open and his tie loose; it was unthinkable.

Too soon the song came to an end. Rosa reluctantly got to her feet, sorry that the show was already over. "Axel was right," she concluded as the two girls went up to their room together."It is a lot nicer here."

Buy here!

Buy here!

"You alright, Ernst?" Christian asked with apparent concern as he poured wine for himself. "The MO said you had a concussion and no other serious injuries, but..." Christian looked at him intently. "What's bothering you?"

Ernst couldn't take the scrutiny. The tension was just too much, or the contrast between the inner tension and the warm, cosy environment was too much. Ernst wasn't someone who could pretend anyway. He burst out, "Christian I'm a wash-out, aren't I?"

"Whatever for? You did a great job putting your Emil down without breaking anything."

"But -- I mean -- that I had to crash at all. I mean...." Too late, Ernst realized that Christian didn't know about the oxygen and that he'd been lost. But they would find out as soon as they investigated. Ernst's head was killing him. He dropped it into his hands and just held it.

"Come on. What's eating you?" Christian urged in a friendly tone.

"My oxygen."

"What about it?" Christian asked confused.

"There wasn't anything wrong with it -- I'd just forgotten to plug it in." Ernst was so ashamed, he didn't dare meet Christian's eyes as he admitted this.

Christian just laughed. Ernst stared at him. "Hell. Who hasn't done that once or twice?"

"But I -- I panicked! I half-rolled and dived instead of staying below the Staffel. And I didn't realize what was wrong 'till I was back on the deck and, and...."

Christian leaned his elbows on the table and looked Ernst straight in the eye. "If you aren't getting any oxygen, you can't think properly. That's all there is to it. It's normal. don't let it get to you. What's important is that you plugged in and tried to catch up with us."

"Yes -- but I couldn't find you."

"Of course not. The weather closed in too fast and the sweep was scratched."

Ernst stared at Christian, hardly daring to believe what he was being told. Christian acted as if he wasn't to blame for what happened. He tried to explain. "I got lost Christian. I didn't know where I was. I kept following the coast, but I couldnt' find anything familiar -- not even Le Harve. I looked and looked, but I couldn't find any familiar landmark. It -- it was just luck that I landed so near the ZG base."

"How long have you been with us, Ernst? Ten days?"

Ernst nodded.

"And how many of those days have we flown? --not even half." Christian answered his own question. "So you've flown in France all of four times, right? and rarely the same route? And in better weather. Any of us might have lost our way in this muck."

Ernst stared at him, almost afraid to believe him, but Christian really seemed to mean it.

"Cheer up, Ernst!" Christian urged with a smile. "If I have to spend the evening with you rather than Gabrielle, than at least try to make it a pleasant evening, all right?"

"Gabrielle? Is that your French girl friend?" Ernst ventured timidly. "Didn't the CO order you to stop seeing her?"

"So what? We've signed a truce with France. Half the Gestapo has French girl friends nowadays! What do they expect us to do? Live like monks? That's not healthy!" Christian delcared with conviction.

Ernst snickered in embarrassment. He'd never had a girl friend, and he was far too inhibited to go to whores. The very thought made him feel dirty. He didn't want it like that. He wanted a nice girl, who was there just for him. She didn't have to be beautiful, just kind and sympathetic and nice. He found himself gazing at his wine, wishing, while Christian continued his commentary.

Christian was telling him about meeting Gabrielle, and somehow he made it all sound very amusing. In fact, Christian soon had Ernst laughing. He forgot about his headach, and getting lost, and crashing. And when he remembered again, it didn't seem so bad.

Excerpt 2: New Assignment

Axel shook out a cigarette, and Christian took it thankfully. Axel gave him a light. As he straightened from bending over the match, the pilot's eyes fell on the two girls, still hovering just within earshot. He smiled at them at once, and Klaudia's alarm signals went off. She took a step backwarks, but it was too late.

"Has the Luftwaffe come up with the delightful idea of training Helferinnen to service aircraft?"

Axel turned back from the waist, saw what Christian had seen, and with a somewhat annoyed frown signalled the girls forward as he explained. "No. They're both in Communications, but Rosa and I met at StG2. After I'd written back about how nice it was here, she got it into her head to follow me over."

Axel had his hand around Rosa's elbow as he introduced her. "Rosa Welkerling." Christian clicked his heels and bowed his head, smiling, but his eyes had already shifted to Klaudia. "Klaudia von Richthofen," Axel duly introduced her, adding for the benefit of the girls, "Christian Freiherr von Feldburg."

Again Christian clicked his heels and bowed to Klaudia. Klaudia was so distressed to find herself attracted to him when she had hardly recovered from what Jako had done to her, that she was immensely relieved when the fat pilot emerged beside them. He distracted the handsome baron, who turned on him to declare triumphantly, "I told you not to worry about me."

"You barely made it," Ernst pointed out.

"Perfect planning, as the CO would say," Christian assured him, flinging an arm over his wingman's shoulders.

"The CO won't say anything of the kind," Ernst retorted with a sour expression.

"He would, if he'd done it," Christian reasoned, and they all laughed a bit more loudly than the joke justified. Christian and Ernst started to turn away, but Christian remembered to politely nod to the girls. Then the pilots were gone and Axel turned to the Helferinnen rather sharply. "We've got work to do. See you later."

"As you like," Rosa answered, miffed, as the started to turn away. Then she stopped and called out, "Axel?"

"Now what?"

"You never looked that nervous when Pashinger was late."

"Arschinger was an asshole."

"And this baron's not?"

"Feldburg? No, he's all right."

....

By about ten pm, Klaudia was falling asleep upright. It had been an eventful day, and she was no longer used to wine with dinner. She stood, hiding a yawn behind her hand, and announced she was turning in.

"I'll come too," Rosa agreed.

They said good night to the other girls and left their little mess, crossing the darkened games room and making for the main stairs. But as they reached the stairs sweeping up from the reception area, they could hear music and singing coming up from the Officer's Bar on the left. "Listen!" Rosa said with delight. "That's Veronica, der Lenz ist da!" When Klaudia looked blankly at her, she added, "You know, by the Comedian Harmonists! Surely you know the Comedian Harmonists?" Rosa might be a good National Socialist, but nothing could ruin her delight in the songs of the Berlin quintet. She tiptoed toward the stairs that led down into the rustic bar with its flagstone floor and beamed ceiling a half-floor below.

Someone was playing a piano very well, and several men were indeed singing in harmony. There was also the stamping of feet and clapping of hands to heard. Rosa tiptoed down four or five steps until, by bending, she could see into the bar itself. In a line with their arms around each other's shoulders, four of the pilots were dancing to the music as they sang.

They had their tunics completely unbuttoned, their ties loosened, and the pilots on the ends -- the fat pilot Ernst Geuke and a man she didn't recognize -- were having some trouple keeping up with the steps. In the centre, very much the motor of the little act, was -- who else? -- Christian Freiherr v. Feldburg....

Klaudia tried to picture Jako doing some kind of can-can with his tunic open and his tie loose; it was unthinkable.

Too soon the song came to an end. Rosa reluctantly got to her feet, sorry that the show was already over. "Axel was right," she concluded as the two girls went up to their room together."It is a lot nicer here."

Buy here!

Buy here!

Published on August 28, 2014 15:30

August 21, 2014

The Catch of the Season

An Excerpt from Chasing the Wind (Kindle edition: Where Eagles Never Flew):

As usual, [his mother] was talking even before she entered the parlour with the tea tray. "...and she left a number where you can call her back."

"Who?""Robin! Haven't you heard a think I've said to you? Virginia Cox-Gordon!"There had been a time when he would have been very excited to hear that Virginia Cox-Gordon had called. He had, shortly, been very interested in her. She was pretty, witty, rich, and he liked being seen with her. But Virginia picked her boy-friends by their pocketbooks, and Robin couldn't afford her. His parental grandfather, Admiral Priestman, had put him through public schools but he flatly refused to pay for anything as "nonsensical" as flying, and so he had only made it through Cranwell on money Aunt Hattie raised by mortgaging her house. As for his Flight Lieutenant's pay, you could book that under "petty cash" as far as the Cox-Gordons of the world were concerned. There were allegedly officers in the Auxiliary Air Force who spent more on a bottle of wine than the regular officers earned in a month. But that was probably exaggerated, Robin relfected soberly. The point was: he hadn't inherited a fortune and he wasn't going to make one either -- and Virginia wasn't going to give sustained attention to anyone without.Besides, Robin reflected on his reaction to his mother's news, he didn't particularly want Virginia's attention anymore. She'd been a bit of a status symbol before the war. Being seen with Virginia had been good for his image, and he'd been flattered that she would go out with him at all. But the fact was, he hadn't given her a thought since the war started in earnest.His mother set the tea-tray down on the coffee table, and Robin took his crutch and hobbled over to sit on the sofa. "I droped by the Mission to see Aunt Hattie today," he remarked."In your condition?" his mother answered, horrified. She had never approved of him 'hanging about' the Seaman's Mission, because he came in contact with 'bad company' there. Robin, on the other hand, had been starved for masculine role models as a boy, and so he had been fascinated by the tattooed nd weathered men that washed up at the Mission. He'd always spent time down there when he could, often helping Cook because the retired seamn had a wealth of fascinating -- and by no means completely sanitized -- stories. "There's a new girl working there. Emily Pryce.""Good heavens! What do you want with the girls Hattie drags in? For all you know she was a you-know-what! She might well be diseased.""With a Cambridge education and quoting John Maynard Keynes?"His mother had not answer to that, but didn't need one. The telephone was ringing out in the hall, and she rushed to answer it."Yes, yes!" Robin heard her say breathlessly into the phone, and then, "He just got in. I'll go fetch him." She rushed back into the sitting room and stage-whispered at Robin: "It's Miss Cox-Gordon!""I don't want--" He thought better of it, took a crutch and limped into the hallway. He took up the receiver. "Hello?""Robin, darling! Ii was so worried. Are you really quite all right?""Brilliant. Wizard. Nothing but a bashed ankle. Cast comes off in a couple of weeks or so. Then I'm back on ops.""So soon? Then we must get together at the first opportunity. What are you doing tomorrow? I'm having a few friends down to the country." She meant her father's country estate in Kent. "Why don't you join us?""Sorry. Can't drive yet. Not 'til the cast comes off. Nice of you to think of me 'though. Just have to wait 'til I'm fit. I'll give you a call.""Look, if you can't drive, how about if I come down to Portsmouth one evening and pick you up?""Wouldn't want to impose. Besides, Portsmouth's pretty grim at the moment. Navy all over the place."Virginia tittered. "Honestly, Robin, there's nothing new about the Navy in Portsmouth. Besides, it must be quite exciting, really. London is dreadfully boring these days. Blackouts and air raid wardens and everybody in some silly uniform -- and, oh yes, you should see the Americans. There seem to be American press people everywhere these days." She interrupted herself to ask him, "You know I've got a job with the Times, don't you?""Congratulations. Society Page?""No! Who cares about that now-a-days? I'm covering London, actually. You wouldn't believe all the silly questions these Americans insist on asking everyone! 'WIll Britain bear up?' 'Can the RAF stop the Luftwaffe?'""Can we?"Virginia tittered again. "You're a card, Robin. You should know.""Haven't the foggiest. Look, Virginia, my aunt just got in, and I must entertain her." He was looking at Aunt Hattie, who - having let herself in - was coming up the stairs. "I'll ring you later in the week. Thanks for calling.""But--"He'd already hung up."Just who was that?" Hattie asked giving him a piercing look."Virginia Cox-Gordon."Hattie's eyebrows went up. She didn't read the gossip pages, but many of her staff -- and of course her sister Lydia -- did. She new exactly who Virginia Cox-Gordon was: daughter of a millionaire, debutante, the "catch of the season" just last year, before the war started."You know your other girl-friends call my flat," she told him in a low, reproachful voice."I'm sorry --""Just how many girls did you give my number to?""Only two." He thought about it. "Three."Hattie sighed and gazed at him sadly."I am sorry they bothered you," Robin insisted, looking sincere. "I told them not to call unless it was an absolute emergency, and --""Yes, well, I'm sure things look very different from your superior male vantage point, but to us poor females here on the ground, the fact that you were last seen duelling with two Messerchmitts over the ruins of Calais in the midst of the worst rout in English history seemed very much like an 'emergency.' I can't say I blame them, but I do wonder about you sometimes....Robin concluded it might not be the best moment to ask her for Emily Pryce's telephone number.

Buy here!

Buy here!

As usual, [his mother] was talking even before she entered the parlour with the tea tray. "...and she left a number where you can call her back."

"Who?""Robin! Haven't you heard a think I've said to you? Virginia Cox-Gordon!"There had been a time when he would have been very excited to hear that Virginia Cox-Gordon had called. He had, shortly, been very interested in her. She was pretty, witty, rich, and he liked being seen with her. But Virginia picked her boy-friends by their pocketbooks, and Robin couldn't afford her. His parental grandfather, Admiral Priestman, had put him through public schools but he flatly refused to pay for anything as "nonsensical" as flying, and so he had only made it through Cranwell on money Aunt Hattie raised by mortgaging her house. As for his Flight Lieutenant's pay, you could book that under "petty cash" as far as the Cox-Gordons of the world were concerned. There were allegedly officers in the Auxiliary Air Force who spent more on a bottle of wine than the regular officers earned in a month. But that was probably exaggerated, Robin relfected soberly. The point was: he hadn't inherited a fortune and he wasn't going to make one either -- and Virginia wasn't going to give sustained attention to anyone without.Besides, Robin reflected on his reaction to his mother's news, he didn't particularly want Virginia's attention anymore. She'd been a bit of a status symbol before the war. Being seen with Virginia had been good for his image, and he'd been flattered that she would go out with him at all. But the fact was, he hadn't given her a thought since the war started in earnest.His mother set the tea-tray down on the coffee table, and Robin took his crutch and hobbled over to sit on the sofa. "I droped by the Mission to see Aunt Hattie today," he remarked."In your condition?" his mother answered, horrified. She had never approved of him 'hanging about' the Seaman's Mission, because he came in contact with 'bad company' there. Robin, on the other hand, had been starved for masculine role models as a boy, and so he had been fascinated by the tattooed nd weathered men that washed up at the Mission. He'd always spent time down there when he could, often helping Cook because the retired seamn had a wealth of fascinating -- and by no means completely sanitized -- stories. "There's a new girl working there. Emily Pryce.""Good heavens! What do you want with the girls Hattie drags in? For all you know she was a you-know-what! She might well be diseased.""With a Cambridge education and quoting John Maynard Keynes?"His mother had not answer to that, but didn't need one. The telephone was ringing out in the hall, and she rushed to answer it."Yes, yes!" Robin heard her say breathlessly into the phone, and then, "He just got in. I'll go fetch him." She rushed back into the sitting room and stage-whispered at Robin: "It's Miss Cox-Gordon!""I don't want--" He thought better of it, took a crutch and limped into the hallway. He took up the receiver. "Hello?""Robin, darling! Ii was so worried. Are you really quite all right?""Brilliant. Wizard. Nothing but a bashed ankle. Cast comes off in a couple of weeks or so. Then I'm back on ops.""So soon? Then we must get together at the first opportunity. What are you doing tomorrow? I'm having a few friends down to the country." She meant her father's country estate in Kent. "Why don't you join us?""Sorry. Can't drive yet. Not 'til the cast comes off. Nice of you to think of me 'though. Just have to wait 'til I'm fit. I'll give you a call.""Look, if you can't drive, how about if I come down to Portsmouth one evening and pick you up?""Wouldn't want to impose. Besides, Portsmouth's pretty grim at the moment. Navy all over the place."Virginia tittered. "Honestly, Robin, there's nothing new about the Navy in Portsmouth. Besides, it must be quite exciting, really. London is dreadfully boring these days. Blackouts and air raid wardens and everybody in some silly uniform -- and, oh yes, you should see the Americans. There seem to be American press people everywhere these days." She interrupted herself to ask him, "You know I've got a job with the Times, don't you?""Congratulations. Society Page?""No! Who cares about that now-a-days? I'm covering London, actually. You wouldn't believe all the silly questions these Americans insist on asking everyone! 'WIll Britain bear up?' 'Can the RAF stop the Luftwaffe?'""Can we?"Virginia tittered again. "You're a card, Robin. You should know.""Haven't the foggiest. Look, Virginia, my aunt just got in, and I must entertain her." He was looking at Aunt Hattie, who - having let herself in - was coming up the stairs. "I'll ring you later in the week. Thanks for calling.""But--"He'd already hung up."Just who was that?" Hattie asked giving him a piercing look."Virginia Cox-Gordon."Hattie's eyebrows went up. She didn't read the gossip pages, but many of her staff -- and of course her sister Lydia -- did. She new exactly who Virginia Cox-Gordon was: daughter of a millionaire, debutante, the "catch of the season" just last year, before the war started."You know your other girl-friends call my flat," she told him in a low, reproachful voice."I'm sorry --""Just how many girls did you give my number to?""Only two." He thought about it. "Three."Hattie sighed and gazed at him sadly."I am sorry they bothered you," Robin insisted, looking sincere. "I told them not to call unless it was an absolute emergency, and --""Yes, well, I'm sure things look very different from your superior male vantage point, but to us poor females here on the ground, the fact that you were last seen duelling with two Messerchmitts over the ruins of Calais in the midst of the worst rout in English history seemed very much like an 'emergency.' I can't say I blame them, but I do wonder about you sometimes....Robin concluded it might not be the best moment to ask her for Emily Pryce's telephone number.

Buy here!

Buy here!

Published on August 21, 2014 15:30

August 14, 2014

"Or close the wall up with our English dead...."

An excerpt from Chasing the Wind (Kindle: Where Eagles Never Flew):

Tea time. Priestman joined the other pilots sitting in the shade of the mess tent. They were drinking tea. No sooner had Priestman sat down than the airman/cook shoved a mug of hot, sweet stuff into his hand. Priestman smiled up at him, "You're a marvel, Thatcher."

"Just doing my job, sir."

"Doing a damned good job, if I may say so, Thatcher."

"Thank you, sir." The airman looked embarrassed, as if he didn't know what to do with appreciation -- and that made Priestman feel guilty; obviously he and his colleagues were a little too sparing with praise and thanks.

The telephone was ringing in the ops tent. They turned their head and stared at the tent, waiting.

"Maybe it is just someone ringing up to see how the weather is over here."

"Or someone calling to ask if there is anything we lack?"

"Maybe someone has just signed a surrender."

No, it didn't look like that. Yardly was standing in the entry, waving furiously at them.

"Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more," Shakespear intoned as he set his mug aside.

"I don't like that damned quote!" Roger told him irritably -- much too irritably. You could tell his nerves were a bit frayed. He'd had an ugly belly landing the other day and hadn't been the same since, really.

"Why ever not?" Driver asked innocently.

Yardly was shouting at them to "get the finger out," but they ignored him. After all, he wasn't flying, and they didn't presume it would make much difference to the war if they were a minute or two later. It was all a cock-up anyway.

"It's the next line," Priestman explained to Driver, putting his own mug aside carefully.

"What's that?"

"Or close the wall up with our English dead," Priestman told him.

***

Priestman couldn't sleep. He was exhausted beyond measure, but everything seemed to keep him awake -- the dampness of the earth, the roughness of his parachute pack under his head, the snoring or uneasy stirring of his companions, the distant bark of navy guns. It should have been reassuring that the Navy was there, he supposed, but that quote from Henry V kept going through his head, too: "Dishonor not your mothers, now attest that those whom you called 'father' did beget you."Wasn't it odd that Shakespear, 400 years ago, could write something that fit so perfectly? There was hardly one among them whose father hadn't been here in France last time around, and they had fought for four years. It was barely two weeks sicne the German offensive had begun -- and it was very nearly over. If Calais fell, they were all trapped....

Two hours later they were scrambled to intercept bombers attacking the British in Calais. Priestman could sense he was in trouble from the start. At take-off, his Hurricane hit a small hole and bounced. He over-reacted pulling back on the stick too soon. He didn't have enough speed. The Hurricane fell back to earth and he was running out of grass. When he did get airborne, he barely cleared the trees. The adrenaline pumping from the near miss, he had to throttle forward to catch up with the others as they swung west toward Calain the sun behind them bright and blinding. It was obvious that they were going to get bounced. But ahead, a gaggle of ugly Stukas was peeling off and going down to drop their loads on the ruins of Calais -- because that was all that was left of the city. The buildings the Stukas were hammering had long since turned into heaps of rubble. still, guns were being fired out of that rubble, and with a twinge of pride Robin realised that there were still British troops down there in that wasteland, and they were flinging defiance back at the overwhelming might of Germany.They were so small, so weak, their arms inadequate for the task facing, and their situation was patently hopeless. In fact, the town had apparently already fallen to the Germans. The ugly swastika flag fluttered over the major buildings, but the Union Jack cracked defiantly from the medieval fortress.Robin hated Stukas more than any aircraft. They were ugly, vicious planes without any kind of natural grace. They had bent wings and massive, fixed undercarriages like the extended claws of an attacking eagle. They had been designed to intimidate without majesty and were even equipped with sirens whose sole purpose was to increase the noise, and so the terror,t hey created as they dived. They symbolised in his mind all that was most objectionable about the Nazis -- the brutality, the brashness, the bragging. Robin was determined to get one -- and confident too.Bringing one down was not the problem. The Hurricane could fly circles around a Stuka, and Priestman, Ibbotsholm, Stillwell and Bennett all brought one down on their first pass. Robin's mistake was that he wanted more. His over-wrought nevers, the near crash on take-off, and now these hated planes harassing the shattered remnants of a gallant British defence, resulted in a dangerous fit of hubris -- just as had happened when he was 15, and again in Singapore. As soon as he'd finished off one Stuka, Priestman started spiralling up the sky to get enough altitude for a new attack. He kept watching the Stukas, afraid they would get away before he could attack again. He was not watching his tail or the sun.When the cannon hit him from behind, he was taken completely by surprise. He reacted as he had taught himself over the last ten days, with a flick quarter-roll and a tight turn. It worked, the Me109 overshot him, and Robin straightened out and started running inland. He'd made a second mistake: he'd forgotten the wingman.The minute he straightened out, machineguns and cannon raked along the side of the Hurricane. He felt as if it had been violently wrenched out of his hands as it spun out of control. Still shaken by the suddenness of the dual attack and the terrifying sensation of losing control of the Hurricane, Priestman was close to panic as he tried to pull out of the spin.Nothing happened.The pedals and stick were dead.His brain registered what had happened. His tail and/or the control cables had been shot away. He had no contrl over the aircraft and it was spinning around faster and faster. The Hurricane was past the vertical, and the earth was spinning so fast it was just a whirling blur.He struggled to get clear of the aircraft, tearing off his helmet to free himself of oxygen and R/T, but the centrifugl force was pinning him to the seat. The hood seemed to jam. He battered hsi hands bloody trying to free it. At the very last minute it broke free, and with the super-human strength of panic he flung himself over the side of the cockpit. But he was took close to the ground. His 'chute didn't have time to open properly.

Buy here!

Buy here!

Published on August 14, 2014 15:30

August 7, 2014

Reviews of "Chasing the Wind"/ "Where Eagles Never Flew"

Perhaps the finest fighter pilot story ever written. 5 December 2013

Helena has written a book that will become a classic. It was rated by Bob Doe, one of the top Battle of Britain fighter aces, as a book that told the story correctly and he was delighted to recommend this to a wider public.

This book will be enjoyed for many years, however many times you read this.

Written from actual events and pilots experiences during the air fighting of the Battle of Britain, it tells the story of just why a few hundred men prevented invasion and the horrors of death camps being a reality in Britain.

Never was so much owed by so many to so few.

These men now have a book to tell it like it was.

Highly recommended.

Paul Davies BoBHSc FRTCA

By Ms. Cathy Howat (Melbourne, Australia) - See all my reviews

(REAL NAME) Amazon Verified Purchase(What's this?)This review is from: Where Eagles Never Flew: A Battle of Britain Novel (Kindle Edition)Six stars, I am a former pilot, RNZAF trained. I knew one of the historical figures in this book. Since leaving flying I have become a nurse and have had occassion to nurse a lot of former fliers, WAAF, Controllers, and ground crew. This book is spot on and tells it like it was. I hope we will see more on the WW2 RAF from this author. There is a sequel, THE LADY IN THE SPITFIORE, but it is not available (yet) as an E-Book, I will be buying it in dead tree format. This book should not be missed

Not just another account of the Battle of Britain! March 22, 2014Schrader has written a great story on the Battle of Britain. She takes you from the early stages of WWII to Dunkirk and back to Great Britain for the Battle of Britain. Not only is the writing very good, with excellent descriptions, but she takes you to the other side where you get a really good look at the Nazi air arm. Enemy airman performing their duties and the realization that they are not so different than the brave men of the RAF.

The reader not only follows the RAF pilots through their life threatening sorties, but also through their off duty times. Men and women living on the edge, here today and gone this afternoon. Life is taken away that quickly. That is why these young pilots lived, drank and loved hard. The mortality rate of your squadron mates is so very high that you better enjoy the time you are here on this blessed English soil. The interesting part of the book is you are treated to a similar outlook by the German fliers.

Rather than get into the book's characters, I would definitely say that if you enjoy reading about historical fiction relating to WWII and specifically the Battle of Britain you don't want to miss "Where Eagles Neve Flew". I beleive you too will thourghly enjoy this book.

Buy Kindle here!

Or in Trade Paperback here!

Or in Trade Paperback here!

Published on August 07, 2014 15:30

July 31, 2014

Reflections on the Battle of Britain

There are few events in British History that are as dramatic or as inspiring as the Battle of Britain. Indeed, Winston Churchill suggested in his famous speech that the Battle of Britain was the British Empire’s “finest hour.”

Pilots “Scramble” very early in the Battle. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

From the point of view of a historian, the Battle of Britain was significant because it brought Hitler’s aggression to a halt for the first time after he came to power in Germany in 1933. Admittedly, Hitler considered his failure to defeat the Royal Air Force in the summer of 1940 an annoyance rather than a major strategic set-back; his real objective was the Soviet Union, and to this day most Germans have never even heard of the Battle of Britain! Yet for Britain, the United States, and occupied Europe, the significance of the Battle of Britain can hardly be over-stated.

If the RAF had been defeated in 1940, the Luftwaffe would have been able to continue indiscriminate day-light bombing almost indefinitely, and paved the way for a German invasion of Britain. Although many doubt this would have been successful, there is no certainty that it would have been repulsed either. The Royal Navy had been seriously weakened by the losses during the evacuation at Dunkirk and was over-stretched trying to protect the Atlantic lifeline. Furthermore, the Royal Army was had been mauled in France and the British Expeditionary Force had abandoned all its heavy equipment in France. In consequence, the British ground forces lacked tanks and artillery for fighting the heavily mechanized Wehrmacht. Churchill was not only being rhetorical when he spoke about fighting a guerrilla war against the invaders!

But the invasion did not take place because the Royal Air Force, or more specifically Fighter Command, prevented the Luftwaffe from establishing air superiority over England. Without air superiority, the Wehrmacht was not prepared to invade. So Hitler (more interested in invading the Soviet Union anyway) first postponed and then cancelled the invasion of Britain altogether.

This was more than a military victory. The Battle of Britain was a critical diplomatic and psychological victory as well. The psychological impact of defeating the apparently invincible Luftwaffe was enormous at the time. The RAF had proved that the Luftwaffe could be beaten, and by inference that the Wehrmacht could be beaten. This fact alone encouraged resistance and kept hope alive all across occupied Europe.

Even more important, as a result of British tenacity and defiance in the Battle of Britain, the United States, which at the start of the Battle had written Britain off as a military and political power, revised its opinion of British strength. Because of the Battle of Britain, the U.S.A. shifted its policy from ‘neutrality’ to ‘non-belligerent’ assistance. With American help, Britain was able to keep fighting until Hitler over-extended himself in the Soviet Union. This in turn made it possible to forge the wartime coalition of Britain, the U.S. and the Soviet Union, which would eventually, defeat Hitler’s Germany.

Yet, any such purely objective assessment of the Battle of Britain does not explain the appeal of the Battle of Britain to people today. There were, after all, many other decisive battles in WWII from Stalingrad to Midway. The appeal of the Battle of Britain is less military and diplomatic than emotional.

The Battle of Britain was a drama that has captured the imagination – and hearts – of all subsequent generations because of just how much hung in the balance and of just how little stood between Britain and a Nazi invasion. The Wehrmacht had just defeated the French in six weeks! The British Expeditionary Force had been rescued by the skin of their teeth in a dramatic, improvised evacuation – but only at the cost of abandoning all its equipment on the beaches of France. Thus, in the Summer of 1940, it seemed like only RAF Fighter Command stood between Britain and invasion, between freedom and subjugation.

Yet RAF Fighter Command was tiny! Even including the foreign pilots flying with the RAF, there were only roughly 1,200 trained fighter pilots in Britain at this time. (Numbers varied due to training, casualties and recruiting.) These men were a highly trained elite that could not be readily replaced. Pilots were not mere “cannon fodder.” They were specialists that took years to train. In the summer of 1940, they stood against apparently overwhelming odds. Churchill – as so often – captured the sentiment of his countrymen when he claimed that “never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

This image of a small “band of brothers” standing up to a massive and invincible foe in a defensive battle for their homeland was reminiscent of other heroic battles – Henry V at Agincourt, Edward the Black Prince at Poitiers, Leonidas and his 300 at Thermopylae. Such battles, pitting a few defenders against a hoard of enemy, have always appealed to students of history and readers of historical fiction like almost nothing else.

Furthermore, it must be remembered that pilots were very, very young (averaging 22 years in age), and they were they were fighting with beautiful, fragile machines that still awed most of their contemporaries. Furthermore, the casualties were devastating. In the short, four month span of the Battle, Fighter Command lost roughly 40% of its pilots. That means that each pilot had only a slightly better than 50% chance of surviving the Battle. Furthermore, the effective casualty rate of killed and wounded was closer to 70%. This situation was aggravated by the fact that, as a rule, the more experienced pilots had a 5-6 times greater chance of surviving than did the replacement pilots coming into the front line with very little flying and no combat experience. The most critical period for a replacement pilot was his first fortnight in a front-line squadron. Many pilots did not survive four hours.

This meant that a smallish core of experienced pilots watched waves of replacements arriving and then being shot-down in a short space of time, until sheer exhaustion wore down even the most experienced pilots. By the end of the Battle, Squadron Leaders, Flight Lieutenants and Section Leaders were increasingly getting shot down as a result of mistakes, inattention, and ‘sloppy flying’ that resulted simply from fatigue.

These are the “human interest” stories that so fascinate us today – the inexperienced teenagers with less than 20 hours on combat aircraft being thrown into the bloody fray, and their experienced commanders, the “killers” who had to shoot down enough German aircraft to convince Goering and Hitler that the Battle could not be won, while at the same time leading, encouraging and advising their young colleagues so they could live to fight another day.

How did they do it?

Obviously one factor was sheer motivation. British pilots were fighting over their homes – and their historical and national heritage – acutely aware of being the last line of defense in a war against a widely abhorred enemy. But this alone would hardly have given them victory. The Poles and Danes and French etc. had also been fighting for their homes and country against the same aggressor.

Technology and organization were other critical factors and these have been analyzed and discussed in great detail in many good history books. I will only mention here radar, without which Britain would certainly have lost the Battle of Britain, and the system of ground control over dispersed fighter squadrons, which was equally important to Britain’s victory in 1940. The Spitfire deserves at least an honorable mention since it was such a magnificent fighter, even if honesty compels me to note that in the Battle of Britain more squadrons were equipped with and more German aircrafts shot down by Hurricanes.

But I would like to draw attention to one aspect of the Battle that I believe has often been overlooked in favor of the above explanations for success. This was the very strong “team spirit” that predominated in the RAF –in sharp contrast to the Luftwaffe at this time. The Luftwaffe enabled and encouraged individual fighter pilots to become “aces.” If a German pilot was an “ace,” he was not only lionized by the press and praised by his peers and superiors -- all the way to Hitler himself, but he was given a wingman and then an entire “Schwarm” to protect him so he could concentrate on killing. This way, German aces accumulated huge scores, sometimes over 100 attributed “kills,” while the highest scoring ace of the RAF, “Johnnie” Johnson, had only 38 recorded “kills.”

Yet the RAF with its ethos of acting as a team inflicted losses on the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain at a rate of almost 2 to 1. Furthermore – and far more important - morale did not break. Given the losses and the sheer physical demands placed upon RAF pilots at the time, it was their ability not only to keep flying but to keep drinking and laughing that awed their countrymen, their leaders and their enemies – when they found out.

“B” Flight, 85 Squadron, July 1940. Courtesy of WAAF Edith Kupp

Furthermore, it was not the pilots alone who won the Battle of Britain. The RAF had worked hard to ensure that its pilots were supported by some of the best trained ground crews in the world. With an ‘apprentice’ program, the RAF had attracted technically minded young men early and provided them with extensive training throughout the inter-war years. In fact, because of a unique program that enabled exceptional “other ranks” to qualify for flying training, many pilots flying in the Battle of Britain had come up from the ranks, starting as mechanics themselves. This made the pilots appreciate their ground crews more than pilots did in other air forces of the time.

Perhaps most important, however, was that at this stage of the war, individual crews looked after individual aircraft and so specific pilots. The ground crews identified strongly with their unit – and ‘their’ pilots. After the bombing of the airfields started in mid-August, the ground crews were themselves under attack, suffering casualties and working under deplorable conditions – often without hot-food, dry beds, adequate sleep and no leave. The ground crews never failed their squadrons. Aircraft were turned around – rearmed, re-fuelled, tires, oxygen, airframe etc. checked – in just minutes.

Last but not least, I would like to note that the RAF from the very start had an exceptionally positive attitude toward women. The RAF actively encouraged the establishment of a Women’s Auxiliary, which by the end of the war served alongside the RAF in virtually all non-combat functions. Even before the start of the war, however, the vital and highly technical jobs of radar operator and operations room plotter, as well as various jobs associated with these activities, were identified as trades especially suited to women. The C-in-C of Fighter Commander, ACM Dowding, personally insisted that the talented women who did these jobs move up into supervisory positions – and be commissioned accordingly. During Battle of Britain over 17,000 WAAF served with the RAF, nearly 4,500 of them with Fighter Command. A number of WAAF were killed and injured and six airwomen were awarded the Military Medal during the Battle. The presence of so many young women is another factor that contributes to its modern appeal.

WAAF in Fighter Command Control Room. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

My novel on the Battle of Britain, Chasing the Wind (Kindle edition: Where Eagles Never Flew), pays tribute to the entire spectrum of participants, male and female, from mechanics and controllers to WAAFs as well as to the pilots. I based my account on the very meticulous records now available from both the UK and Germany to ensure that the raids, casualties, and claims each day are correct. Yet the most important research was reading the memoirs of dozens of participants and corresponding with others to try to get the atmosphere “right.” My greatest moment as a historical novelist came when I received a hand-written letter from a man I had only read about up until then: RAF Battle of Britain “ace” Bob Doe. Wing Commander Doe wrote to tell me I had “got it smack on the way it was for us fighter pilots,” and said that Chasing the Wind was “the best book” he had ever read about the Battle of Britain. It doesn’t get any better than that for a historical novelist! Here’s a video teaser about the novel. Click here!

Here’s a video teaser about the novel. Click here!

(Note the Kindle Edition was published under the title Where Eagles Never Flew.) Buy here!

(Note the Kindle Edition was published under the title Where Eagles Never Flew.) Buy here!

Pilots “Scramble” very early in the Battle. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

From the point of view of a historian, the Battle of Britain was significant because it brought Hitler’s aggression to a halt for the first time after he came to power in Germany in 1933. Admittedly, Hitler considered his failure to defeat the Royal Air Force in the summer of 1940 an annoyance rather than a major strategic set-back; his real objective was the Soviet Union, and to this day most Germans have never even heard of the Battle of Britain! Yet for Britain, the United States, and occupied Europe, the significance of the Battle of Britain can hardly be over-stated.

If the RAF had been defeated in 1940, the Luftwaffe would have been able to continue indiscriminate day-light bombing almost indefinitely, and paved the way for a German invasion of Britain. Although many doubt this would have been successful, there is no certainty that it would have been repulsed either. The Royal Navy had been seriously weakened by the losses during the evacuation at Dunkirk and was over-stretched trying to protect the Atlantic lifeline. Furthermore, the Royal Army was had been mauled in France and the British Expeditionary Force had abandoned all its heavy equipment in France. In consequence, the British ground forces lacked tanks and artillery for fighting the heavily mechanized Wehrmacht. Churchill was not only being rhetorical when he spoke about fighting a guerrilla war against the invaders!

But the invasion did not take place because the Royal Air Force, or more specifically Fighter Command, prevented the Luftwaffe from establishing air superiority over England. Without air superiority, the Wehrmacht was not prepared to invade. So Hitler (more interested in invading the Soviet Union anyway) first postponed and then cancelled the invasion of Britain altogether.

This was more than a military victory. The Battle of Britain was a critical diplomatic and psychological victory as well. The psychological impact of defeating the apparently invincible Luftwaffe was enormous at the time. The RAF had proved that the Luftwaffe could be beaten, and by inference that the Wehrmacht could be beaten. This fact alone encouraged resistance and kept hope alive all across occupied Europe.

Even more important, as a result of British tenacity and defiance in the Battle of Britain, the United States, which at the start of the Battle had written Britain off as a military and political power, revised its opinion of British strength. Because of the Battle of Britain, the U.S.A. shifted its policy from ‘neutrality’ to ‘non-belligerent’ assistance. With American help, Britain was able to keep fighting until Hitler over-extended himself in the Soviet Union. This in turn made it possible to forge the wartime coalition of Britain, the U.S. and the Soviet Union, which would eventually, defeat Hitler’s Germany.

Yet, any such purely objective assessment of the Battle of Britain does not explain the appeal of the Battle of Britain to people today. There were, after all, many other decisive battles in WWII from Stalingrad to Midway. The appeal of the Battle of Britain is less military and diplomatic than emotional.

The Battle of Britain was a drama that has captured the imagination – and hearts – of all subsequent generations because of just how much hung in the balance and of just how little stood between Britain and a Nazi invasion. The Wehrmacht had just defeated the French in six weeks! The British Expeditionary Force had been rescued by the skin of their teeth in a dramatic, improvised evacuation – but only at the cost of abandoning all its equipment on the beaches of France. Thus, in the Summer of 1940, it seemed like only RAF Fighter Command stood between Britain and invasion, between freedom and subjugation.

Yet RAF Fighter Command was tiny! Even including the foreign pilots flying with the RAF, there were only roughly 1,200 trained fighter pilots in Britain at this time. (Numbers varied due to training, casualties and recruiting.) These men were a highly trained elite that could not be readily replaced. Pilots were not mere “cannon fodder.” They were specialists that took years to train. In the summer of 1940, they stood against apparently overwhelming odds. Churchill – as so often – captured the sentiment of his countrymen when he claimed that “never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

This image of a small “band of brothers” standing up to a massive and invincible foe in a defensive battle for their homeland was reminiscent of other heroic battles – Henry V at Agincourt, Edward the Black Prince at Poitiers, Leonidas and his 300 at Thermopylae. Such battles, pitting a few defenders against a hoard of enemy, have always appealed to students of history and readers of historical fiction like almost nothing else.

Furthermore, it must be remembered that pilots were very, very young (averaging 22 years in age), and they were they were fighting with beautiful, fragile machines that still awed most of their contemporaries. Furthermore, the casualties were devastating. In the short, four month span of the Battle, Fighter Command lost roughly 40% of its pilots. That means that each pilot had only a slightly better than 50% chance of surviving the Battle. Furthermore, the effective casualty rate of killed and wounded was closer to 70%. This situation was aggravated by the fact that, as a rule, the more experienced pilots had a 5-6 times greater chance of surviving than did the replacement pilots coming into the front line with very little flying and no combat experience. The most critical period for a replacement pilot was his first fortnight in a front-line squadron. Many pilots did not survive four hours.

This meant that a smallish core of experienced pilots watched waves of replacements arriving and then being shot-down in a short space of time, until sheer exhaustion wore down even the most experienced pilots. By the end of the Battle, Squadron Leaders, Flight Lieutenants and Section Leaders were increasingly getting shot down as a result of mistakes, inattention, and ‘sloppy flying’ that resulted simply from fatigue.

These are the “human interest” stories that so fascinate us today – the inexperienced teenagers with less than 20 hours on combat aircraft being thrown into the bloody fray, and their experienced commanders, the “killers” who had to shoot down enough German aircraft to convince Goering and Hitler that the Battle could not be won, while at the same time leading, encouraging and advising their young colleagues so they could live to fight another day.

How did they do it?

Obviously one factor was sheer motivation. British pilots were fighting over their homes – and their historical and national heritage – acutely aware of being the last line of defense in a war against a widely abhorred enemy. But this alone would hardly have given them victory. The Poles and Danes and French etc. had also been fighting for their homes and country against the same aggressor.

Technology and organization were other critical factors and these have been analyzed and discussed in great detail in many good history books. I will only mention here radar, without which Britain would certainly have lost the Battle of Britain, and the system of ground control over dispersed fighter squadrons, which was equally important to Britain’s victory in 1940. The Spitfire deserves at least an honorable mention since it was such a magnificent fighter, even if honesty compels me to note that in the Battle of Britain more squadrons were equipped with and more German aircrafts shot down by Hurricanes.

But I would like to draw attention to one aspect of the Battle that I believe has often been overlooked in favor of the above explanations for success. This was the very strong “team spirit” that predominated in the RAF –in sharp contrast to the Luftwaffe at this time. The Luftwaffe enabled and encouraged individual fighter pilots to become “aces.” If a German pilot was an “ace,” he was not only lionized by the press and praised by his peers and superiors -- all the way to Hitler himself, but he was given a wingman and then an entire “Schwarm” to protect him so he could concentrate on killing. This way, German aces accumulated huge scores, sometimes over 100 attributed “kills,” while the highest scoring ace of the RAF, “Johnnie” Johnson, had only 38 recorded “kills.”

Yet the RAF with its ethos of acting as a team inflicted losses on the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain at a rate of almost 2 to 1. Furthermore – and far more important - morale did not break. Given the losses and the sheer physical demands placed upon RAF pilots at the time, it was their ability not only to keep flying but to keep drinking and laughing that awed their countrymen, their leaders and their enemies – when they found out.

“B” Flight, 85 Squadron, July 1940. Courtesy of WAAF Edith Kupp

Furthermore, it was not the pilots alone who won the Battle of Britain. The RAF had worked hard to ensure that its pilots were supported by some of the best trained ground crews in the world. With an ‘apprentice’ program, the RAF had attracted technically minded young men early and provided them with extensive training throughout the inter-war years. In fact, because of a unique program that enabled exceptional “other ranks” to qualify for flying training, many pilots flying in the Battle of Britain had come up from the ranks, starting as mechanics themselves. This made the pilots appreciate their ground crews more than pilots did in other air forces of the time.

Perhaps most important, however, was that at this stage of the war, individual crews looked after individual aircraft and so specific pilots. The ground crews identified strongly with their unit – and ‘their’ pilots. After the bombing of the airfields started in mid-August, the ground crews were themselves under attack, suffering casualties and working under deplorable conditions – often without hot-food, dry beds, adequate sleep and no leave. The ground crews never failed their squadrons. Aircraft were turned around – rearmed, re-fuelled, tires, oxygen, airframe etc. checked – in just minutes.

Last but not least, I would like to note that the RAF from the very start had an exceptionally positive attitude toward women. The RAF actively encouraged the establishment of a Women’s Auxiliary, which by the end of the war served alongside the RAF in virtually all non-combat functions. Even before the start of the war, however, the vital and highly technical jobs of radar operator and operations room plotter, as well as various jobs associated with these activities, were identified as trades especially suited to women. The C-in-C of Fighter Commander, ACM Dowding, personally insisted that the talented women who did these jobs move up into supervisory positions – and be commissioned accordingly. During Battle of Britain over 17,000 WAAF served with the RAF, nearly 4,500 of them with Fighter Command. A number of WAAF were killed and injured and six airwomen were awarded the Military Medal during the Battle. The presence of so many young women is another factor that contributes to its modern appeal.

WAAF in Fighter Command Control Room. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

My novel on the Battle of Britain, Chasing the Wind (Kindle edition: Where Eagles Never Flew), pays tribute to the entire spectrum of participants, male and female, from mechanics and controllers to WAAFs as well as to the pilots. I based my account on the very meticulous records now available from both the UK and Germany to ensure that the raids, casualties, and claims each day are correct. Yet the most important research was reading the memoirs of dozens of participants and corresponding with others to try to get the atmosphere “right.” My greatest moment as a historical novelist came when I received a hand-written letter from a man I had only read about up until then: RAF Battle of Britain “ace” Bob Doe. Wing Commander Doe wrote to tell me I had “got it smack on the way it was for us fighter pilots,” and said that Chasing the Wind was “the best book” he had ever read about the Battle of Britain. It doesn’t get any better than that for a historical novelist!

Here’s a video teaser about the novel. Click here!

Here’s a video teaser about the novel. Click here! (Note the Kindle Edition was published under the title Where Eagles Never Flew.) Buy here!

(Note the Kindle Edition was published under the title Where Eagles Never Flew.) Buy here!

Published on July 31, 2014 09:40

July 25, 2014

Knight of Jerusalem -- Search for the Cover

My current project is a biographical novel of Balian d'Ibelin in three parts. The first book in the trilogy will be released this fall under the title: Knight of Jerusalem. The publisher has provided three mock-up covers. Please tell me which you like best by taking part in the poll.

The cover text below will tell you a little more about the content of the book -- and I'll provide more information about it as the publication date gets closer.

Balian, the landless son of a local baron, goes to Jerusalem to seek his fortune. Instead he finds himself trapped into serving a young prince suffering from leprosy. He appears condemned to obscurity and an early death — until the king dies unexpectedly making the leper boy King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem.

The Byzantine princess Maria Comnena was just 13 years old when she arrived in the Kingdom of Jerusalem to cement the alliance between Latin Jerusalem and Greek Constantinople. Despite her excellent education and intelligence, she is little more than a pretty doll in the eyes of her husband, a man almost three times her age. Then suddenly the King is dead and at just 20 years of age Maria finds herself a wealthy widow with a vulnerable two-year-old daughter on her hands.

Meanwhile, the charismatic Kurdish leader Saladin has united the forces of Islam and vowed to drive the Christians into the sea. Only a united and vigorous defense can save the Christian kingdom, but not only is the king young, inexperienced and mortally ill, the barons are divided among themselves and the militant orders bitter rivals. As the King tries to chart a course to salvage his Kingdom from certain obliteration, he leans increasingly upon his boyhood friend, Balian d’Ibelin.

The cover text below will tell you a little more about the content of the book -- and I'll provide more information about it as the publication date gets closer.

Balian, the landless son of a local baron, goes to Jerusalem to seek his fortune. Instead he finds himself trapped into serving a young prince suffering from leprosy. He appears condemned to obscurity and an early death — until the king dies unexpectedly making the leper boy King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem.

The Byzantine princess Maria Comnena was just 13 years old when she arrived in the Kingdom of Jerusalem to cement the alliance between Latin Jerusalem and Greek Constantinople. Despite her excellent education and intelligence, she is little more than a pretty doll in the eyes of her husband, a man almost three times her age. Then suddenly the King is dead and at just 20 years of age Maria finds herself a wealthy widow with a vulnerable two-year-old daughter on her hands.

Meanwhile, the charismatic Kurdish leader Saladin has united the forces of Islam and vowed to drive the Christians into the sea. Only a united and vigorous defense can save the Christian kingdom, but not only is the king young, inexperienced and mortally ill, the barons are divided among themselves and the militant orders bitter rivals. As the King tries to chart a course to salvage his Kingdom from certain obliteration, he leans increasingly upon his boyhood friend, Balian d’Ibelin.

Published on July 25, 2014 05:43

July 17, 2014

A Tribute to Friedrich Olbricht and the "General's Plot" Against Hitler

General Friedrich Olbricht was the first of literally thousands of Germans to fall victim to the National Socialist purge that followed the failed coup of 20 July 1944. It is fitting that he should die first, because -- with the exception of Generaloberst Ludwig Be, who died almost simultaneously -- no other figure in the German Resistance to Hitler had been such a consistent and effective opponent of the regime.

Olbricht was an opponent of Hitler from before he came to power. This was because on the one hand he recognized Hitler's demonic and dangerous character; and on the other hand he had been one of the few Reichswehr officers who served the Weimar Republic with conviction and sincere loyalty. Because he did not view the Republic as a disgrace and long for some kind of national 'renewal,' he never allowed himself to believe that Hitler and his movement might be a positive force for the restoratoin of German honor and power.

Furthermore, because Olbricht recognized the legitimacy of the Republic, he discerned the illegal nature of the Nazi regime from the very start. Nor was he enchanted by Hitler's early successes. Regardless of how much he may have welcomed an expansion of the Reichswehr, he saw the murders of June 30, 1934 as the barbaric acts of lawlessness that they were. He did not look the other way or rationalize what had been done. As a result, his moral standards were not corrupted by rationalization of, much less complicity in, crimes. Because Olbricht's opposition and resistance were motivated by moral outrage at the policies and methods of the Nazis, his opinion of and attitude toward the Nazi regime never softened despite internal and international successes.

By 1938, Olbricht's opposition to the increasingly dangerous and lawless Nazi regime had reached the point where he was prepared to consider a coup d'etat against the government. From 1940 onwards he belonged to the inner core of a conspiracy centered around Generaloberst Beck, which actively sought to bring down the Nazi regime. Starting in early 1942, he developed the clever tactic of using a legitimate General Staff plan, Valkyrie, as the basis for a coup against the government. By the end of 1942, according to Gestapo reports, he argued "with increasing urgency that the military must act regardless of how difficult the coup might be." After two failed assassination attempts in early 1943, he recruited Claus Graf Stauffenberg for the Resistance. On July 15 1944, he issued the Valkyrie orders two hours in advance of the first possible opportunity for the assassination.

On 20 July 1944, Olbricht waited only for confirmation that an 'incident' had occurred before he set the coup in motion for a second time in a week. Once the coup started, he was, according to all accounts, consistently energetic and forceful in trying to drive the coup forward to success. He did not call it off when Keitel denied Hitler was dead, and he arrested Fromm and others. If one gives credence to the reports of eyewitness -- rather than the most-mortem commentary of historians -- at no time on 20 July did Olbricht hesitate or lose heart.

As for Claus Graf Stauffenberg, all his burning desire to 'save Germany' would have served him little if his next assignment after his severe wounds in North Africa had landed him in any other of the almost infinite number of jobs available to a lieutenent colonel in the summer of 1943. HIs energy and commitment would have brought no benefit to the German Reistance if he had found himself serving, say, on the staff of Military District XVII in Vienna, or -- as a former cavalry officer -- as coordinator of the supply remounts for ain increasingly horse-dependent Wehrmacht. But Olbricht chose Stauffenberg as his new Chief of Staf and so gave him the opportunity to become one of the leading figures in the German Resistance to Hitler.

Olbricht and Stauffenberg worked together well. Stauffenberg brought fresh energy, fresh perspectives and new dynamism to the coup, but he did not replace Olbricht. Rather he complimented him. While Olbricht was disciplined and mature, canny and experienced, Stauffenberg was passionate, flamboyant and creative. Olbricht and Stauffenberg saw themselves as a team, as comrads, working together towards the same goal. And no description of Olbricht and Stauffenberg would be complete without mentioning that htey liked working together. One of the secretaries who worked in the small office between their respective offices reported: "When the two of them were together, you heard so much laughter, just laughter."

It is Olbricht's tragedy that his pivotal role in the German Resistance to Hilter has been overshadowed by others and his contributions underestimated, demeaned or forgotten.

(The above is paraphrased from the concluding chapter of

Olbricht also plays a key supporting role in my novel about the German Resistance An Obsolele Honor

(Kindle edition: Hitler's Demons: A Novel of the German Resistance.)

Published on July 17, 2014 15:00

July 3, 2014

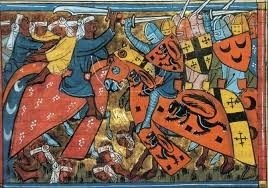

The Battle of Hattin

July 4 marks not only U.S. Independence Day but also the anniversary of the Battle of Hattin, fought in 1187.

The Battle of Hattin

The devastating defeat of the combined Christian army at the Battle of Hattin on July 4, 1187, was one of the most significant disasters in medieval military history. Christian casualties at the battle were so enormous, that the defense of the rest of the Kingdom of Jerusalem became impossible, and so the defeat at Hattin led directly to the loss of the entire kingdom including Jerusalem itself. The loss of the Holy City, led to the Third Crusade, and so to the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich I “Barbarossa”, and extended absence from his domains of Richard I “the Lionheart.” Both circumstances had a profound impact on the balance of power in Western Europe. Meanwhile the role of the critical of Pisan and Genoese fleets in supplying the only city left in Christian hands, Tyre, and in supporting Richard I’s land army resulted in trading privileges that led to the establishment of powerful trading centers in the Levant. These in turn fostered the exchange of goods and ideas that led historian Claude Reignier Condor to write at the end of the 19thCentury that: “…the result of the Crusades was the Renaissance.” (The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1291 AD, The Committee of Palestine Exploration Fund, 1897, p. 163.)