Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 15

December 27, 2022

Writing as Praying

Since the second grade, I have been inspired (not to say compelled) to write novels. I have never been able to explain why, nor how I ‘select’ the topics of my novels. The ideas for novels occur to me spontaneously, sometimes as very vague and ephemeral ideas, which I then refine and redefine at a rational level, sometimes very specifically as in the case of Kit Moran. No matter how much research and work I later put into a novel, the irrational and inexplicable manner in which the initial spark of inspiration occurs has always suggested to me that my novels were genuinely “inspired” not conceived.

With time, I came to realize that the process of creative writing is my way of communicating with God. Creative writing is not about asking God for something. It is not about me articulating my thoughts and feelings to Him. Rather, it is about receivingideas, guidance and understanding. When I sit down to write, I open both my mind and my subconscious to inspiration. As I write, I am almost always surprised and excited by the unexpected reactions of my characters. They then become my teachers, giving me new insight into human nature. Again and again, I have felt a wonderful sense of awe at the end of writing a scene, a chapter or a book, when suddenly I start to understand things that I had not rationally grasped when I started writing.

Because I am an imperfect human being, I do not always understand what I “hear,” nor do I always have the skill to describe and convey to readers the insights I have gained during the process of writing. Nor do I claim that my insights are relevant to everyone. We all have an individual relationship with the Divine, and we must all communicate with Him in our own way. Nevertheless, I firmly believe that like a good meal or a beautiful building, a divinely inspired work of fiction is something that can comfort, sustain and inspire more than just the creator. For that reason, I share the products of my “prayers” – my books – with others.

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

December 20, 2022

Why I write Part 7 - To Reach a Greater Audience

I'm perfectly aware that I do not write books for the "general public" (whatever that is!). My books are not relevant to everyone and do not interest everyone. I do not expect "everyone" -- not even my closest friends and family -- to take an interest in, for example, Ancient Sparta or 13th century Cyprus. Why should they share these arcane interests simply because they happen to have been born in the same family or have worked with me somewhere in the world? My friends and family like me for the things we share, not necessarily the things I write about.

But there are thousands, even tens of thousands of people around the world who do share my interest in Sparta, the crusader states or aviation in the Second World War. They have studied these topics academically or as a hobby. They read every book they can get their hands on about these topics of interest -- fiction and non-fiction, film or documentary. Through my writing, I connect with them, and they are my loyal readers and fans. They follow my blog and facebook entries on the historical background of my novels. They recommend other sources and novels. We belong to the same little club.

And then there are readers who aren't particularly interested in the subjects of my novels and would never pick up a non-fiction book about them to learn more, but are interested in "a good read." These are people who wouldn't read a book "because it's set in 12th century Cyprus," but might read a book "full of lessons we'd be foolish to forget." (Chanticleer Review, The Last Crusader Kingdom) They may not be interested in the Third Crusade, but want to read "the Best Biography of 2017." (Envoy of Jerusalem). Readers who couldn't care less about Emperor Frederick II may yet be intrigued by a hero described by Kirkus Reviews as "like Shakespeare's portrayal of the young prince Hal." (Kirkus, Rebels against Tyranny)

In short, because fiction is about characters (people) as much (if not more) than about historical events, it appeals to a wider audience. I will never forget that when working on my dissertation about the German Resistance to Hitler, I had a conversation with Graefin Yorck, the widow of Peter Graf Yorck von Wartenburg. She confessed to me that "all she ever knew" about the American Civil War she had learned from Gone with the Wind. The same is true for millions of people who accept Shakespeare's Richard III as history or have learned about Thomas Cromwell from Hilary Mantel.

It is my hope that readers will come to share my interest in ancient Sparta, the crusader states and the men who defended democracy in the air during WWII through my books. If not, I hope they will nevertheless enjoy the stories for themselves and want to read more from my pen.

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

December 13, 2022

Why I Write Part 6 - To Critique

In reflecting on why I write, I have to confess that I use my books to express social criticism of the world as I see it. Indeed, I have often argued that all historical fiction says more (whether consciously or not) about the time in which it was written than the time it allegedly describes.

We can see this clearly in art and film. Here are some examples.

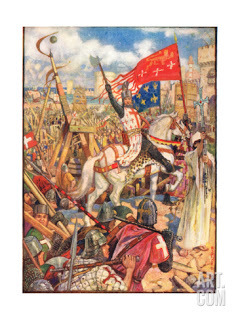

Compare, for example, these two depictions of Richard the Lionheart.

To the left. an contemporary 12th century manuscript illustration.

To the right a painting by Henry Justice Ford, from the end of the 19th century.

Below two Hollywood versions.

To the left, Richard and Eleanor in "The Lion in Winter" (1968) - which depicts Richard as homosexual.

To the right, Richard in Ridley Scott's "Robin Hood," (2010), where he is a bloodthirsty fool.

Likewise, although all my novels are firmly grounded in historical fact and describe historical events and characters as authentically as possible, the choice of subject and my interpretation of events and characters is a result of my experience with the modern world. Just as critics of totalitarian systems from the Soviet Union to Nazi Germany often disguised their critique as science fiction, I use my historical novels to render commentary on events, trends, attitudes and behavior I see around me.

One example of this is my treatment of the Greek Orthodox opposition to Lusignan rule on the island of Cyprus at the end of the 12th century. The opposition is entirely understandable and justified, but like so many rebellions (including the one I was witnessing while writing the book in Ethiopia), rebel actions often hurt innocent people -- indeed the most vulnerable and least powerful of people, rending their actions far less heroic than the cause would suggest. The Last Crusader Kingdom is a commentary not only on a 12th century event but also on rebellions, insurgency, and good governance generally.

Another example is my current work on the Berlin Airlift that explores the duplicity, cynicism and brutality of a heartless, totalitarian regime. The behavior of the Russians may echo what is now happening in Ukraine, yet the tactics of fake news, constant lying, denial of facts and science, and fundamental contempt for human decency and fair-play is even more at evidence in the behavior of the American fascist party, the so-called "Republicans."

I firmly believe in my motto that we learn about ourselves as human beings by studying the past. When I write about the past I explicitly examine issues and patterns of behavior that I have seen in my own life. Sometimes those are positive experiences that restore my faith in mankind. Sometimes, however, I feel it is important to highlight negative characteristics or behaviors that, unfortunately, keep repeating themselves through the ages.

I am always delighted when my readers recognize the parallels to modern personalities and events!

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

December 6, 2022

Why I Write Part 5 - To Share

Sharing is akin to teaching, but I wanted to handle it separately in this series on "Why I Write" because I wanted to underline that not all an artist shares with the reader is knowledge.

When writing non-fiction only the fact and analysis count, but when writing fiction emotions, intuition, and dreams count too. An novelist shares with the reader a wide spectrum of precious, personal feelings -- feelings about people, ideas and things.

All my novels reflect my personal experience with life. This isn't about facts but about world-view -- my understanding of human nature, of politics, of marketing and parenting, of love and hate etc. etc. These subjective components are largely what make it possible for two authors to write about an identical subject and produce startlingly different works. Schiller's Joan of Arc is different from George Bernard Shaw's. Which one you like best will largely depend on your world view, which of the writers strikes a cord with your soul, not your mind.

Teaching is all about passing on facts and knowledge, whereas sharing is about opening one's heart to the readers and showing them how you see the world. Looked at another way, the information that is taught belongs in the realm of plot and setting; the philosophy and worldview that is shared belongs to the realm of theme and character development.

Let me take an example from Rebels against Tyranny. It is a fact that Emperor Frederick II held two of the Lord of Beirut's sons hostage for their father's good behavior. Beirut seized two royal castles anyway and used these to bargain a truce with the Emperor. When the Emperor released the hostages, including Beirut's sons, the latter had been badly mishandled. Those are the facts of the case, but there many -- all justifiable and plausible interpretations -- of what the characters felt about the events. Was Beirut callous and indifferent to what might befall his sons? Did they blame him -- or the Emperor -- for their maltreatment? And just how did two youths raised in luxury and privilege respond to abruptly being prisoners, and abused ones at that? I postulate, based not on evidence but intuition, that the experience would have had a profound impact on their character.

Or another example, we know that the Lusignans invited Franks who had lost their lands and livelihoods in the wake of the disaster at Hattin to re-settle on the Island of Cyprus. The historical record says nothing about how these immigrants were received by the native population. My descriptions are based not on evidence and facts but on my experience of waves of immigration by peoples with a different faith (or race, ethnicity etc) in today's world. The discussions in The Last Crusader Kingdom about how to ease tensions between the groups are not founded in learned facts but in my personal exposure to contemporary events. My most recent novels focus on WWII and the stresses faced both by airmen fighting the war and those they loved, who lived in constant fear of loss. Again, the facts are easy to find and describe; it is the emotions that require more than research. Writing a good novel requires empathy for one's characters -- but that is rarely attained without the permission and complicity of the latter. Which is why novels need to be written from the heart as well as the head.

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

November 29, 2022

Why I Write Part 4 - To Educate

The urge to pass on knowledge to others is probably embedded in our DNA to help the survival of the species. I'm no exception, and since I like to research topics that are either controversial or less familiar to people, I always find myself with plenty of knowledge I want to share. My preferred means of teaching is to write novels that incorporate the information I have gained through my research.

The challenge is to teach readers about unfamiliar places, societies, events and technologies without making them feel they are in school! Key to this is to avoid disrupting the narrative with information and descriptions, aka "data dumps."

The problem, of course, is that no one who is completely familiar with a culture or period is able to see what makes it unusual. Here's a real-life example. A very well-educated African, who traveled over-seas for the first time as an adult was amazed to discover that toilets did not need to smell. He had assumed that since shit smells, toilets had to smell, and it was a revelation to discover that if properly cleaned and flushed they need not do so. In short, no one who has grown up in the advanced industrial world is likely to comment on toilets that don't stink, while no one from Africa would comment on those that do.

The historical record is consistently distorted by this phenomenon. For example, because all boys who went to school in ancient Greece learned to read and write, none of the foreigners who described the Spartan school mentioned that the boys learned to read and write. That was obvious and didn't need to be said. Instead, they commented at length on the things that were unique about the Spartan educational system, e.g. the boys could be flogged, or elected their own leaders etc. Modern readers, not seeing reference to Spartan boys learning to read, often mistake this for proof the boys didn't learn when in fact it is only proof that the observer didn't think it was worthy of mention. What this means when writing a novel is that the inhabitants of the world depicted usually know about their society and surroundings and therefore would not comment on them. The author, therefore, must find a way to tell the readers about things that the characters already know and understand. One way to deal with the problem is to create a context for learning that makes discovery of new facts a force that moves the story forward. A key device for doing this is to introduce Point-of-View characters who are outsiders or novices because they are themselves learning. For example, because most readers know very little about Ancient Sparta, I chose to open my novel The Olympic Charioteer through the point-of-view of an Athenian, a stranger coming to Sparta for the first time in his life who is shocked and confused by one thing after another. In this way, I was able to describe the unique and unfamiliar environment of my novel not as "data-dump" but in a series of episodes that moved the plot forward. Having a foreigner as a major character, however, is not always possible, but there are other devices for making explanations (education) occur more normally and in context. For example, in my novel "Moral Fibre" the device for explaining things was to take the reader through operational training along with the central character. I.E. the reader learns along with the protagonist at each stage of the process. In my novella "Lack of Moral Fibre" the device was a series of discussions between the protagonist a psychiatrist trying to piece together the causes of a temporary break down.

Having a foreigner as a major character, however, is not always possible, but there are other devices for making explanations (education) occur more normally and in context. For example, in my novel "Moral Fibre" the device for explaining things was to take the reader through operational training along with the central character. I.E. the reader learns along with the protagonist at each stage of the process. In my novella "Lack of Moral Fibre" the device was a series of discussions between the protagonist a psychiatrist trying to piece together the causes of a temporary break down. Sometimes, however, rather than building the entire novel around the learning process, I find it useful simply to introduce secondary or tertiary characters who from time to time provide a fresh perspective. This enables me to describe aspects of the setting that the principle characters would not naturally comment upon. For example, in the latter Middle Ages, knights and nobles knew heraldry inside out, but if they described it as they would have done ("or, a cross pate gules", for example), it would be meaningless to us. A peasant observer, on the other hand, could describe a knight's shield in terms we understand -- a yellow backdrop with a flared, red cross on it. By temporarily describing, say, a joust between two protagonists from the point of view of an apprentice sneaking off for some excitement, it is possible to provide more information without interrupting the narrative or making the characters behave anachronistically.

The utility of changing perspectives from time to time in order to teach better (and incidentally add depth of perspective) is one of the reasons I abhor the modern fashion for writing everything in the first person. There is truly nothing wrong with the prose of John Steinbeck or Leo Tolstoy. The obsession with not changing points of view is a modern fad that will hopefully die a natural death -- soon. Writers should be free to share their knowledge in whatever way is most effective and entertaining because it is only if the teaching is effective that readers will truly learn.

Visit http://www.helenapschrader.com/books.html to find the perfect gift for someone you know loves learning!

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

November 22, 2022

Why I Write Part 3: Questioning Cliches

Today I continue my series on why I write by looking at how the desire to question the popular narrative has often given birth to a novel. When confronted by the sharp contrast between popular perceptions and scholarly assessments of an age or society, I'm often inspired to write books that challenge popular misconceptions. My goal is to provoke my reader into questioning common cliches and conventional wisdom along with me.

It all started with the German Resistance to Hitler. Raised by my Danish mother on tales of the heroic Danish Resistance to Hitler it came as a shock to learn, while still in graduate school, that there had been a German Resistance too. After all, the Danes (and French and Poles and Russians) had all been fighting an evil invader, a brutal and monstrous outsider. The German Resistance to Hitler, on the other hand, was fighting their own government, their own institutions and ultimately their fellow-citizens. Unlike the other resistance movements, the German resistance was not nationalist but moral in character.

It all started with the German Resistance to Hitler. Raised by my Danish mother on tales of the heroic Danish Resistance to Hitler it came as a shock to learn, while still in graduate school, that there had been a German Resistance too. After all, the Danes (and French and Poles and Russians) had all been fighting an evil invader, a brutal and monstrous outsider. The German Resistance to Hitler, on the other hand, was fighting their own government, their own institutions and ultimately their fellow-citizens. Unlike the other resistance movements, the German resistance was not nationalist but moral in character. That got me thinking -- and questioning -- the common assumptions about Nazi Germany and the Germans of this period. This led me to nearly twenty years of research, a move to Germany and ultimately a PhD from the University of Hamburg. My dissertation was based on previously untapped primary sources and enabled me to reconstruct the role of one of the leading members of the conspiracy against Hitler. It was a ground-breaking biography which received first-rate reviews in every major German newspaper and sold out within three months. And all because I had started questioning what was being said not only by students but what was in the history books as well.

After so many years focused on one of the most inhumane, corrupt, brutal and cynical periods of human history -- not to mention the dreadful fates of those few who futilely attempted to oppose the forces of evil, I literally never wanted to see another book, film or article about the Nazi period. I needed a completely new focus for my research and writing.

After so many years focused on one of the most inhumane, corrupt, brutal and cynical periods of human history -- not to mention the dreadful fates of those few who futilely attempted to oppose the forces of evil, I literally never wanted to see another book, film or article about the Nazi period. I needed a completely new focus for my research and writing. I found my new "cause" in Ancient Sparta. Again, I discovered (more by chance than choice) that Spartan women enjoyed education and economic power at a time when Athenian (and most other Greek) women were treated like the women of the Taliban. What? How? Why was that? I asked.

I found my new "cause" in Ancient Sparta. Again, I discovered (more by chance than choice) that Spartan women enjoyed education and economic power at a time when Athenian (and most other Greek) women were treated like the women of the Taliban. What? How? Why was that? I asked. My questioning led me to discover a Sparta radically at odds with the common image fed us daily by Hollywood and even pseudo-history sources like The History Channel and Wikipedia. I was off again - questioning, learning and exploring. My travels took me to Sparta, and an encounter with a fertile, rich and beautiful place, which made my questions all the more incessant and pointed. I've shared the answers to my questions on my website: http://spartareconsidered.com and of course, in my novels set in Ancient Sparta.

More recently, as a result of my encounters with Islam, I started to question the politically correct version of the crusades. Nigeria in the age of Boko Haram, the systematic assaults on moderate Imams in Ethiopia, developments in Sudan, Somalia, Iran, Iraq, Turkey and, yes, Afghanistan make the politically correct and popular portrayal of the Medieval Muslim world as a place of tolerance, benevolence and non-violence hard to fathom. I started questioning what I had learned at home and in school, and I came to my own conclusions -- based very much on the recorded facts and the writings of contemporaries, both Christian and Muslim.

More recently, as a result of my encounters with Islam, I started to question the politically correct version of the crusades. Nigeria in the age of Boko Haram, the systematic assaults on moderate Imams in Ethiopia, developments in Sudan, Somalia, Iran, Iraq, Turkey and, yes, Afghanistan make the politically correct and popular portrayal of the Medieval Muslim world as a place of tolerance, benevolence and non-violence hard to fathom. I started questioning what I had learned at home and in school, and I came to my own conclusions -- based very much on the recorded facts and the writings of contemporaries, both Christian and Muslim.

History is never black and white, it is always full of shades of grey. Humans are by nature complex and fallible. Good people sometimes make bad decisions or do unpleasant things; even predominantly bad people usually have redeeming features. Indisputable facts are rare because the historical record is almost always subjective, biased or just plain incomplete. Narratives can be interpreted in conflicting, even contradictory ways. People, all people, have friends and enemies, and how we see them hundreds of years later will depend on whether the former or the later wrote the documents we discover. Precisely because history is so complex and nuanced, questioning is never wrong. That desire to question the conventional and familiar view of things is one of my driving reasons for writing historical fiction.

History is never black and white, it is always full of shades of grey. Humans are by nature complex and fallible. Good people sometimes make bad decisions or do unpleasant things; even predominantly bad people usually have redeeming features. Indisputable facts are rare because the historical record is almost always subjective, biased or just plain incomplete. Narratives can be interpreted in conflicting, even contradictory ways. People, all people, have friends and enemies, and how we see them hundreds of years later will depend on whether the former or the later wrote the documents we discover. Precisely because history is so complex and nuanced, questioning is never wrong. That desire to question the conventional and familiar view of things is one of my driving reasons for writing historical fiction.

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

November 15, 2022

Why I Write Part 2: To Explore

This is the second installment in my series on why I write.

Today I look an my desire to explore.

Last week I argued that learning is an essential part of my writing, so essential that I choose to write in part out of a desire to learn more about something that attracts my curiosity. But writing fiction is not just about writing down what we learn, it is also about using imagination to go beyond the known -- to explore the unknown.

Some of that exploration can be physical. Working on a creative-writing project is a great excuse to travel to places I've never been before. I love travel, so this is an extra bonus. No sooner had I started my Jerusalem Trilogy than I announced to my husband that it was "essential" that we travel (at last!) to Jerusalem.

It helped that we were living in Ethiopia, just a four hour flight from Tel Aviv, and that there were daily pilgrimage flights. The trip enabled me to explore many sites important to my novels -- Jerusalem itself, Bethlehem, Ascalon, Jaffa, Acre, and Caesaria, Ibelin (modern Yavne), and the Battlefield of Hattin. The visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher alone, however, would have justified the trip, and enabled me to write a more authentic and convincing book. I always wince when I read descriptions of the Holy Land, including the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, that have clearly been written by authors who have never been.

It helped that we were living in Ethiopia, just a four hour flight from Tel Aviv, and that there were daily pilgrimage flights. The trip enabled me to explore many sites important to my novels -- Jerusalem itself, Bethlehem, Ascalon, Jaffa, Acre, and Caesaria, Ibelin (modern Yavne), and the Battlefield of Hattin. The visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher alone, however, would have justified the trip, and enabled me to write a more authentic and convincing book. I always wince when I read descriptions of the Holy Land, including the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, that have clearly been written by authors who have never been. Yet even more important than this physical exploration of places is the mental exploration of attitudes, emotions, motives and more. Research may reveal a simple fact such as, for example, the daughter of Baldwin d'Ibelin, Baron of Ramla and Mirabel, married the brother of Guy de Lusignan. History also tells us that Baldwin hated Guy so much that he preferred to surrender his entire inheritance and abandon his wife and son to go into exile in Antioch rather than do homage to Guy de Lusignan. But what about his daughter? How did she feel? Did she sympathize with her father? or her brother-in-law? Did her husband blame her for her father's dramatic and public condemnation of his brother? Was there marital strife and tension? As a novelist, it is my job to explore possibilities. To try to find the explanation that seems to ring most consistent with known facts -- and human nature.

Or to take another example, a lot has been written about the concept of and procedures around the finding someone "lacking in moral fibre" (LMF) -- from the point of view of those not so labelled. Men who witnessed others been humiliated and the psychiatrists who treated men found LMF by their superiors have written about the phenomenon, but I have located no first-hand accounts by someone who underwent the process. We also know a great deal about the circumstances that drove aircrew to refuse to fly without a medical reason, triggering LMF proceedings. The first-hand accounts describing those circumstances, however, were never written by men refused to fly. In short, the memoirs we have were written by men who experienced the same conditions yet responded differently. A historian can go no further, but a novelist can step beyond the known historical facts and explore the psychological realm, applying an understanding of human nature and empathy to imagine what went on. From such a journey of exploration came my novella Lack of Moral Fibre and the longer novel, Moral Fibre.

Riding the icy, moonlit sky,

Riding the icy, moonlit sky, they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

November 8, 2022

Why I Write Part I - To Learn

This seems like as good a time as any to ref

lect on why I write -- and to share those thoughts with my loyal fans and followers. In this seven part series, I will explore the seven most important motivations, namely: 1) to learn, 2) to explore, 3) to question, 4) to educate, 5) to share, 6) to critique, and 7) to reach a larger audience.

It would probably surprise no one if I said that I read in order to learn, but writing to learn likely strikes many as putting the cart before the horse. Surely one doesn't write about something unless they already know about it?

True. But that is precisely the point.

If I am intrigued by a topic (period, culture, event etc.) enough to want to write about it, then I am setting myself on a course of study. In order to be able to write about this topic, I will have to do my research. I'm not someone who can just dash off a short-story based on a casual thought or a snippet of information I've stumbled across. I envy those who can write like that! But I'm at heart a historian and I can't write even a short story without knowing about things like how people dressed, kept warm, what they ate, how they traveled, what their religious beliefs were likely to be etc. etc.

If I'm going to write, I'm going to have to research all those things, so there's no point getting started unless I'm 1) willing to invest that effort and 2) going to use what I learn for more than one project. In other words, I may read a book simply because someone recommends it to me and I will be the richer for reading, but if I want to write about something I need to learn more. It is not enough to know about the events or even the people described, I must also understand the environment in which the events unfold. That requires learning about, for example, climate, geography, and contemporary architecture. I also need to describe, as I noted earlier, what people were likely to have eaten, how they dressed, the kind of entertainment they would have been able to enjoy, and the means of transport at their disposal. I need to understand social structures, legal norms, religious beliefs and the economics of the time. In other words, by choosing to write about a topic, I ensure that I thoroughly learn about it in much greater detail than would be the case if I simply read about it.

You may also remember your parents or teachers saying that "to teach once is to learn twice." Writing is much the same. What I have read but not written about, I am far more likely to forget. What I have written about I learn with an intensity that stays with me for many years.

My current learning adventure is a deep-dive into the tense, complex and politically critical story of the Berlin Airlift 1948-1949. It builds upon the research I did both for my novel on the German Resistance to Hitler and my books on aviation.

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

November 1, 2022

Accuracy vs Authenticity

There is a difference between historical accuracy and historical authenticity.

Historical accuracy gives historical fiction credibility --

but historical authenticity is what makes it fly.

As a rule, it much easier to get all the facts right, than to capture the atmosphere of a past era. Yet the difference between naked accuracy and an authentic feel is like the difference between the detailed diagram (above) of a Lancaster and an evocative photo of the same subject (below).

As a rule, it much easier to get all the facts right, than to capture the atmosphere of a past era. Yet the difference between naked accuracy and an authentic feel is like the difference between the detailed diagram (above) of a Lancaster and an evocative photo of the same subject (below).

Nowadays, the sequence of historical events and the important political or military developments of any era can be found easily. Fact form the content of large numbers of readily accessible history books not to mention Wikipedia essays or Quora answers. Any author wondering about simple facts (e.g. when did battle x take place, who won, what were the casualties, what consequences did it have? How many wives and children did King xx have? Where was famous person xxx born, go to school and find employment?) only needs to "google" them. Of course, complications can result if different sources give different answers to the same question, but any good historian learns how to compare and analyze sources, to resolve apparent contradictions and/or select the personally most compelling explanation.

Nowadays, the sequence of historical events and the important political or military developments of any era can be found easily. Fact form the content of large numbers of readily accessible history books not to mention Wikipedia essays or Quora answers. Any author wondering about simple facts (e.g. when did battle x take place, who won, what were the casualties, what consequences did it have? How many wives and children did King xx have? Where was famous person xxx born, go to school and find employment?) only needs to "google" them. Of course, complications can result if different sources give different answers to the same question, but any good historian learns how to compare and analyze sources, to resolve apparent contradictions and/or select the personally most compelling explanation. Atmospherics, on the other hand, can't be "googled" at all. You can't ask "what was it like being a Corinthian woman in 5th century BC?" You can't even get a coherent (much less comprehensive) answer asking about "how were Russian women pilots in WWII treated by their comrades?" The atmospherics which give a novel an authentic feel have to be constructed carefully by the author.

On the one hand, this requires researching objective factors such as architecture, fashion, means of transportation, geography, vegetation and climate. In other words, the author must become familiar with the environmental factors that will determine the setting or external features of the world in which the characters "live." This can be trickier than it sounds. For example, novels set in the crusader states routinely depict the Kingdom of Jerusalem as a desert wasteland (the Sahara was used for filming of "The Kingdom of Heaven," for example). In fact, however, the Kingdom of Jerusalem was famous for it's gardens, water-intensive agriculture such as sugar-cane production, and cities surrounded by orchards and other vegetation. Yes, pilgrims who generally spent only the summer in the crusader states often reported on the heat and dust, but the Mediterranean has heavy rains in the winter months and, furthermore, the Latin states in the Levant were very advanced in the use of aqueducts while also investing heavily in widespread irrigation.

Other problems arise from a shallow understanding of things we think we know about. Few novelists writing a novel set in the 18th century would forget that people back then rode horses, but unless they have had more than a passing encounter with horses they tend to fall into the pitfall of thinking that all horses are the same and anyone can easily ride any horse without difficulties, and also forget that horses needed to be fed, watered and rested frequently. Or, to use another example, authors know that people in the past used sailing ships, but too few authors take the time to become familiar with the sailing characteristics of various craft. Too many people nowadays apparently don't know that a sailing ship can't sail into the wind, and that ships could rarely sail directly to any point. Another frequent mistake is to be imprecise when doing research and assume that armor or plumping or clothing was the same throughout the entire Middle Ages, for example. Getting the environmental details right is essential to setting the stage for a book. An absence of detail -- or worse yet, the wrong details -- can ruin a book just as surely as flat characters or a boring plot.

Yet, when you get down to it, finding out about climate, costumes and technology is really just a matter of doing enough research. Far more difficult is discovering information about subjective aspects of a bygone era. Things like:

how a social or economic system impacted daily life,how the legal system could play havoc with the best laid plans of men,

how religious beliefs inhibited sexual behavior, how family structures and inheritance laws disrupted lives and the like. Depending on the period in which the book is set, there may be good social histories that address some of these issues, but there might not. Surer guides to these kinds of issues are diaries, letters and memoirs written by people who lived in a specific era. It is vital, however, to read multiple documents from as many sources as possible in order to distinguish general conditions from unique experiences and perspectives. One of the great advantages of writing about the more recent past is the greater ease of access to these kinds of sources. When writing about the last century, for example, we have tens of thousands of digitalized newspapers, film archives, etc. etc. Certainly, my research on the Battle of Britain and Bomber Command were made easier by the scores of memoirs and online archives of interviews.

Yet even such apparently reliable sources can deceive -- not because they are wrong but rather because they often don't explain aspects of life that were "self-evident" or normal to those living at the time, but not to us. I recently loved a film that I found very convincing, only for someone who had lived through the event depicted to furiously point out everything that was wrong with the details.

All any author can do is his/her best, but being aware of the importance of getting the atmospheric details right is a good first step. Unlike a work of non-fiction, a good novel must always appeal to the emotions and psyche, not just the mind, of the reader.

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com

October 24, 2022

The Basis of a Historical Novel: Research

There is probably no other genre of fiction which requires quite so much research as historical fiction. Indeed, many readers will be surprised to hear that the research required for writing good historical fiction is more comprehensive than that for writing straight history.

Over the years, I've done a lot of historical research. I did academic research for my dissertation. I did research for non-fiction histories on women pilots, the Berlin Airlift and, most recently, the crusader states. Each research project was unique and each came with its own set of challenges and rewards. The availability of primary sources varies from era to era and topic to topic. Access to visual records -- paintings and photographs -- can be radically different and the ability to visit locations or experience modes of transport depend on a variety of factors. Yet, without question the research required for a work of non-fiction was more narrowly focused than for fiction. Academic research particularly is about putting forward a new thesis or uncovering new sources for what is inevitably a narrow, highly specialized topic.

A writer of historical fiction, on the other hand, has to understand -- and be able to describe -- the entire world in which the characters live. For example, my non-fiction comparison of women pilots in WWII looked in detail at the process for recruiting, training, and employing women pilots in the UK and the US. It catalogued their rates of pay, their accomplishments, the public and official recognition they received. But it did not -- and did not need to -- talk about contemporary fashion, food, film and music. There was no need to discuss rationing or politics or social mores. Yet a novel featuring women pilots would need to depict these "extraneous" things and all of them would need to be research.

In addition, when writing non-fiction, an author uses her own voice. This can be as contemporary, chatty and informal or as sophisticated and erudite as the author wants. The author can decide what tone to set and what vocabulary to use. In a novel, in contrast, the characters speak (at least some of the time) and they have to sound like men and women not of the present but the age in which the novel is set. This is more than a matter of avoiding anachronisms, it is about learning what the contemporary slang, jargon, swear-words etc. were.

As a reader, I have repeatedly been irritated by historical novelists who don't do their homework with regard to these atmospherics. Too many novice historical novelists stop doing research when they know the chronology of key events. Others get both the facts and the window-dressing right (i.e. fashions, technology), but they don't take the time to learn about the "soft" or more amorphous features of the age and society in which their novel plays out. Yet an understanding of legal systems, religious beliefs, social customs and sexual mores, for example, are arguably far more important than getting the cut of the dresses right.

Fortunately for me, I love doing historical research precisely because it opens to many doors and provides so many insights into the diversity and complexity of the human experience.

they took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent.

Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one bomber pilot, his crew and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

or Barnes and Noble.

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

Disfiguring injuries, class prejudice and PTSD are the focus of three heart-wrenching tales set in WWII by award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

"Where Eagles Never Flew" was the the winner of a Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

For more information about all my books visit: https://www.helenapschrader.com