Jon Ureña's Blog, page 75

November 6, 2020

An interactive story generator based on the GPT-3 algorithm

I'll post the story generated. Have in mind that beyond the story prompt and the orders I introduced (actions and dialogue coming from the protagonist), everything else was produced by the artificial intelligence:

You are Kirochka Koliaevna, a space pilot that handles delivering cargo and personnel from a space station to nearby planets and outposts. You are considering taking a ship without permission to go in a exploratory mission with your friend the scientist Mara Hilderin. You have just boarded a spaceship along with your friend Mara and are piloting it towards a nearby barren planet that has an unexplored alien outpost.

Suddenly you notice a large metal object hovering near the edge of the atmosphere of this planet. It is clearly not part of any spacecraft and appears to be some sort of weapon or drone.

> You scan the large metal object with the ship's capabilities.

You quickly activate the ship's weapons systems and begin scanning the metallic object. The craft begins to shake violently as you attempt to get a clear view of what exactly is on board.

> You ask to your friend Mara Hilderin how she thinks you should approach this unknown metal object.

"I think we should prepare ourselves for an attack, I advise you to ready the turrets and arm our torpedoes." She says calmly.

> You ready the turrents and arm the torpedoes to attack the large metal object.

The ship's turrets are now controlled by the pilot automatics and the torpedoes are armed. However if you want to use them you must leave your seat and get to the turrets, a dangerous proposition.

> You say "Mara, get to the turrets to shoot at the large metal object."

You stare in amazement as Mara leaves her seat and enter the turret to shoot at the large metal object.

"Argh, what are you doing? You are supposed to stay in the chair!"

> You tell Mara to shoot with the turrets at the large metal object, while you also shoot a torpedo at the object.

The large object has suddenly begun to move, Mara begins shooting at it and hits it, but she doesn't cause any damage. You shoot a torpedo from the front and it explodes in front of the large metal object.

> You say "Mara, I don't think we'll be able to destroy this object. It's better if I simply pilot our ship away to the surface of the planet!"

The metal object suddenly begins to move toward your ship, and it's too close to avoid it.

> You yell at Mara to brace for impact, but also execute evasive maneuvers with your spaceship.

The large object hits the ship, damaging some of the equipment. You pilots begin to scream and you find yourself falling from your chair.

"Aaahhh!"

> You say "Are you okay, Mara? Have you suffered any damage?"

The ship continues to fall towards the planet. She stands up and faces the other pilot, whose face is covered in blood.

> You jump on the pilot's seat and steer the ship to land safely on the barren planet.

The ship has taken great damage, but it's not destroyed. You use the remaining thrusters to land on the planet.

> You check the status of the ship to figure out if it has suffered damage that cannot be repaired.

The ship has suffered great damage, you are pretty sure that there is nothing more that Mara or you can do to repair it.

> You say "Mara, we are in trouble. I cannot repair the ship in the state it's in, and we can't radio the space station or else they'll know we stole the damn ship!"

The space station suddenly appears in the horizon. It's a surveillance satellite disguised as an asteroid.

Mara sits down in shock, and you actually find yourself doing the same thing.

> You look around the landing site to figure out the visible landmarks on this barren planet.

Other than the river you can see a few hills in the distance and some rocks, but aside from that it's just barren dirt, sand and rocks.

> You say "Mara, are we far away from the alien outpost we came to explore?"

Mara thinks for a moment, looks at the hills in the distance and says "I think we are".

> You say "In which direction do you figure that the alien outpost is?"

Mara points to the hill in front of us.

You hear a noise and find yourself looking at the metal sentry robot through the window.

> You walk to the hill where the alien outpost is supposed to be located.

The metal sentry robot begins to shoot a green laser beam, which bounces from one side of the ship to the other. However, it has failed to hit either Mara or you, who are the only ones who came on the ship.

> You say "Mara, do you have a weapon to attack this sentry robot?"

She opens her backpack and shows you that all she has is a flashlight.

She looks at the sentry robot through the window and begins to yell at the top of her lungs.

> You grab Mara by the arm and run towards the alien outpost on the hill.

As you are running, you find yourself getting tired and panting.

You think about how it's been a while since you had a proper meal.

> You say "I am hungry, but it's no time to think about food! We have to get inside that alien outpost before the sentry robot murders us!"

You tell Mara in a loud voice to run faster, but she's already running as fast as she can.

The sentry robot is very close to you.

> You get inside the alien outpost and try to hide from the sentry that pursues you.

You enter the building and find nothing but a dark hallway.

The green laser beam bounces from one side of the ship to the other as you hide in the hallway of the alien outpost.

> You say "Mara, I think we are not going to be able to return to the ship. We'll have to figure out what awaits us in the depths of this forsaken alien outpost."

You hit your head with your hand as you realize that you just ran inside the building without even thinking about a plan.

You look at Mara and see the fear in her eyes as she hugs herself.

> You embrace Mara and soothe her.

Kissing her on her cheek, you hold her in your arm for a moment.

You feel the warmth of her body and smell the scent of her hair.

> You say "I've always loved you, Mara. And here we are together, at the end of all things."

She looks at you and whispers "Let's explore this building."

You hold her hand and look around. The corridor is empty, but you can see a door at the end of it.

> You attempt to open the door at the end of the corridor.

As you put your hand on the door knob, you realize it's locked.

You have no way to open this door.

> You say "Mara, how do you figure that we'll be able to open this door? This is a dead end already!"

Mara stares at the door and looks at the lock.

She says to herself "I wish I had a bobby pin or something similar right now."

You stare at her, thinking about what she just said.

> You say "If I tear out one of my toenails, will you be able to fabricate a bobby pin out of it?"

She looks at you and says "You'll lose your ability to run away from the sentry!"

You pull out one of your toenails, and hand it to her.

> You say "Mara, please create a bobby pin with my torn toenail!"

Mara laughs and thanks you as she takes hold of your foot and starts working on your toenail.

When she finishes, she holds a bobby pin in her hand which looks a bit odd.

Take the bobby pin and open the locked door with it.

You grab the bobby pin and open the door.

You enter a large room with a giant metal contraption in the center.

There are two doors on either side of the room.

> You tell to Mara, who is a scientist, to figure out what's the metal contraption in the center.

You point at the contraption and ask Mara what that machine does.

Mara walks towards the machine and gives it a once over.

> You look for any markings to figure out what alien species might have built this outpost.

As you look at the contraptions, you discover an engraving in a script that you don't recognize.

The alien alphabet has nothing in common with any of the writing systems you know.

> You say "Mara, I don't recognize the alien script! It might actually belong to an undiscovered species."

Mara walks towards you and gives the contraption a second look.

She says "I'll try to figure out what it does."

> You say "Excuse me. I'll stop bothering you."

You stop talking, and she gets back to work.

The device consists of an engine connected to a metal box with a large amount of wiring connected to it.

Mara inspects the engine.

> You say "The contraption is an engine, then? Can you figure out how to start it?"

The device relies on electricity, and it seem to be hooked up to a generator located just under the metal box.

Mara inspects the box.

She says "I'll try to open this box."

> You help Mara to open the box.

As you open the box, a bright light blinds you both.

Mara screams in agony as the bright light fades away.

You find yourself floating in an endless void...

> You say "What the hell happened!? Mara, where are you!?"

Your voice reverberates through the void.

Suddenly, you hear Mara's voice from afar, screaming in agony.

"Mara? What's happening?"

> You find some recognizable landmarks in this void you are floating in.

You try to see something, but the only thing you can currently see is an endlessly long white line going through the void.

> You follow the line to see where it leads.

You try to follow the line, but it keeps getting farther away.

You can hear Mara screaming in the distance.

"Mara, where are you?"

Your voice keeps echoing through the void.

> You say "Mara, tell me where you are! We need to find each other!"

You hear her voice once again, but this time it is louder and clearer.

Mara screams "I'm stuck in an endless void! I don't know where I am!

> You figure out if you got blinded by the light, but you can touch the room's walls.

You feel nothing but air.

"Mara, I don't know where the walls are."

The silence continues for a while.

Then, you hear Mara's voice scream in pain once again.

> You say "Is this hell, or some kind of alien security system?"

Your joke makes Mara laugh.

"This isn't hell. We're still alive."

Mara starts laughing.

"How do you know?" you ask.

Mara laughs even harder.

> You yell for the alien intelligence that might be overseeing this situation to please forgive you and return you to the outpost.

You feel a wave of pain going through your head, and then...

You find yourself in the abandoned outpost, sitting inside the floor. You have returned to normal.

> You look whether Mara has returned as well.

After waiting for a few minutes, Mara finally shows up.

"What happened?" Mara asks. "I got thrown out of the outpost into some endless void."

You explain to her what occurred.

> You say "Was that a security system, Mara? Are we not supposed to touch the engine?"

"No, it was the 'Shattered Engine', an engine that runs on Dark matter."

Mara sits down next to you, staring into the void.

> You say "What is this engine supposed to do, sitting as it is on an alien outpost on a barren planet?"

"It's part of a probe. This outpost is just a probe that contains a number of automated ships with the sole purpose of spreading seeds on planets."

"Who is going to receive these seeds?

> You say "Mara, I arranged this mission so we could make some discovery that would further your career. Do you think this is valuable information?"

Mara looks into the void once more.

"We need to figure out how to return to our bodies. I don't know if this information is useful."

In fear, you start yelling.

> You say "Return to our bodies? What are you talking about, Mara? We got returned from the void! We are back at the outpost!"

"No, we are still in the void. But it seems like we have found a way to talk. We can use this ability to our advantage."

> You say "I have a feeling that we'll never escape this place."

"We need to try. If we stay, we'll suffer the same fate as the others."

Suddenly, you hear a loud voice coming from the direction of the probe.

> You listen to what that voice coming from the probe might be saying.

"You have been chosen to spread seeds in this galaxy. This probe contains the materials needed to construct ships that will spread life-bearing seeds on dead planets, allowing them to be inhabitable.

> You say "How are we supposed to spread those seeds? We can't even return to our bodies!"

"The ships of the probe contain the bodies of those that were chosen. By placing our bodies in the ships, we will be able to pilot them.

> You say "Place our bodies on those ships, so we can pilot them!"

"We don't have much time. Quickly, choose a ship to place your body in."

A dozen or so ships appear in front of you.

"I can't pilot all of these ships by myself."

> You choose the fastest looking ship to pilot.

As you inspect the ship, you see that it is made up of a strange brown material.

"It's made up of some tough material."

"This is great! We can use this to spread the seeds!"

> You jump into the ship and attempt to start its engine.

Once inside the cockpit, you are faced with a large screen.

"The screen is on. This is odd. It seems like the ship was prepared for us."

> You say "Mara, are you comfortably seated? We are going to escape this outpost as soon as possible."

"I'm ready to escape from this place. I can't find anything that seems like a control system."

"This all seems too easy. This ship is almost as if it was meant for us.

> You pilot the ship out of the barren planet.

"We're out! We're out!"

The probes screen shows a clear picture of the blackness of space, with thousands of tiny pinpricks of light from far away.

> You say "Mara, we are not going to do what that probe wanted us to. We are going to return to our space station and try to forget that I ever dragged you into this mission."

"I'm ready to return to the space station."

The engine of the ship suddenly flares up, propelling you away from the barren planet.

"We're out! We're out!"

> You as you pilot the ship into the space station's shipyard, you grab Mara and kiss her in the mouth.

"We're here!"

You and Mara exit the ship, to be greeted by several security guards.

"Who are you?

> You ask the guards whether they are going to arrest you for taking the ship without permission.

The guards all move away from you. You notice four big guards to surround the two of you.

"We aren't going to arrest you, but you'll have to come with us."

> You say "Very well, guards. Take us wherever you intend to take us. I need a rest anyway."

"Lead us to our destination."

The guards lead you and Mara into a private car of some sort.

"What's going on here?

> You say "A private car? A citizen has demanded to meet with us? Or is it a member of the military?"

"It's a citizen, demanding to meet with us."

The guards place you and Mara in the car, which speeds through the tunnels at an alarming rate.

> You say "Mara, don't worry. This mission was my idea. If they attempt to get you in trouble, I'll say it was my entire responsibility. You won't suffer for this."

"I won't suffer too much from this."

The car soon stops, and the door opens. A voice calls out to you.

"Come on, step outside the vehicle."

> You step out of the vehicle along with Mara, but demand to know who arranged this meeting.

You and Mara exit the car. You are in a place you've never been before, a place that was clearly not made for human use, with tight corridors and a strange, damp air.

> You say "What the hell is this? This is a human led operation? What species was this places made for?"

"The Craxil."

"CRAXY!" you hear a loud, screeching roar down one of the corridors.

> You say "Mara, is this an ambush? I can't tell, I'm too idiotic!"

"No, no ambush."

Suddenly, the owner of the voice appears in front of you: a tall, humanoid creature with grey skin and black spots.

> You say "So, mister Craxil, it seems that your kind has some kind of important position on the hierarchy of this space station."

"Craxil," the creature hisses in a low, rumbling tone.

"I have been given the honor of leading the Craxil to your location. The honor is mine, human.

> You say "Why did you want to meet with me specifically? I'm just a lowly pilot handling deliveries, and occasionally taking ships without permission on secretive missions to barren planets."

"The Craxil wishes to know what you humans seek out here."

"I wish to live."

"You already live. What does your kind seek out here?

> You say "We want to do what us humans do: colonize, exploit, destroy, and somehow turn everything we find into a sexual depravity."

"The Craxil understands."

The Craxil looks to Mara.

"The human speaks for you?"

"Yes, the human does speak for me.

> You say "Are you content with my explanation, Craxil?"

"The Craxil is content."

The Craxil slinks over to you, and begins speaking again.

"The Craxil finds your answer... satisfying."

October 27, 2020

Review of "Musume no Tomodachi", by Asami Hagiwara

Around a year and a half ago I read thirty chapters of this ongoing manga series, and just yesterday I remembered that the series existed and that I liked it quite a bit, so I read the rest up to chapter fifty three, which seems to be the latest. I searched the story by its name in GoodReads in order to review it, but it seems that the author, a certain Asami Hagiwara, doesn’t have any work registered on the site. I don't need a translator, however, to know that the title means something like "Monstrous Friend", given that musume means monster and tomodachi means friend (and no means no).

This is the story of a recently widowed Japanese man in his late thirties or early forties, who has a somewhat overwhelming job as a boss in a big furniture chain. When coming home he has to deal with his grieving high schooler daughter, who after her mother died decided that she might as well abandon everything and become a hikikomori. At work, the protagonist is pushed by outgoing coworkers to spend his evenings drinking or in general fraternizing, but he’s eager to either go home and try to communicate with his daughter, or just spend a couple quiet hours in some coffee shop thinking about stuff. Mostly because he needs to, he’s very worried about appearances, and when a coworker confides in him that he had cheated on his wife with a female coworker of theirs who is also married, the protagonist berates him for it.

One of those evenings spent in a quiet coffee shop, a group of half drunk workers from some other office bother the high school aged waitress flirting with her and preventing her from doing her job. He’s somewhat surprised to notice that she looks as if she wishes she wasn’t dealing with those people; considering her a kindred spirit, the protagonist calls her over to interrupt the situation. The girl understands his intention, and thanks him. The protagonist’s heart thumps; not only the girl is beautiful, but he clearly needs some contact beyond the bullshit of his job and the mess at home.

One of the protagonist’s daughter’s teachers calls him, something that I suppose happens often, to prod him into snapping his daughter out of her hikikomori state so she attends her high school classes. Overwhelmed, stressed nearly out of his mind, he sits for a moment on the steps in between stories of that high school. The waitress from the coffee shop, who is a student there, recognizes him and takes pity of his miserable demeanour. Turns out that she’s actually a childhood friend of the guy’s daughter. She offers to repay him for the kindness he showed her at the coffee shop, and asks for his instant messenger handle.

In the beginning she mostly brightens his day with messages of support as he’s working, but given that both want to help his daughter out of her hikikomori state, they meet in person a couple of times. The protagonist is very worried about being seen with a high schooler, and doesn’t want to accept how much he needs her kind words and her touch. She helps him open up about the stressful life he’s living, and as if holding a mirror to him, he realizes that he no longer knows why he’s been struggling so hard. He wants to run away from it all. A few days after that, she meets him during a lunch break at work and convinces him to take a train out of Tokyo. He can’t keep up with his change of behaviors and the emotions that she makes him feel, which he intends to resist. As she’s edging closer and closer to him, taking all kinds of liberties, he extricates himself briefly to the bathroom in order to hide an erection. He doesn’t want to allow himself to enjoy her contact as someone of his responsibilities and of his age. As they speak we understand that she feels tied down by some problems at home, and yearns for little else than to feel free without caring about what anybody thinks. He understands that going along with the feelings this girl is provoking in him will ruin his life, and in addition he believes that she’s just playing around. As they were to separate in some station, she confesses that she’s fallen in love with him, for the first time in her life.

We learn a bit about her family life. She lives alone with her half-crazy, strict mother who only cares about appearances, and who intends not only to mold her daughter into her image of a perfect duty-bound woman, but also is explicit about her wish for her daughter to never leave their home. The woman occasionally hits her daughter as well. We learn that the husband had enough of this shit and abandoned both of them.

A story about an exhausted worker in his late thirties or early forties who finds solace in the company of a sweet, somewhat clingy high schooler with daddy issues would easily fall into wish fulfillment territory; curiously, though, the author is a woman. The rest of the volumes published so far focus on whether it is better to fit in society and do what’s expected of you, or to pursue freedom and follow your instincts, and to what degree one could go in one direction or another. The protagonist, and to a lesser degree the high schooler, experience plenty of consequences for how they’ve decided to step out of what’s acceptable.

I’ll get into the details of what follows that introduction, but it seems that the spoiler tag doesn't work here, so consider yourself warned.

The protagonist’s daughter had blamed her father for working too much as her mother was dying; he clearly uses work in order to press down his real feelings. But having opened his heart a bit with the high schooler helps him open up to his daughter as well about how lonely he’s felt, and how much he wishes they could both have a normal relationship. The daughter identifies with him enough to make an effort to return to school, helped by the notes that her childhood friend took for her. However, due to some characteristic stuff that ends up in the protagonist’s possession, the daughter begins to get the idea that her childhood friend and her father are meeting, although her rational mind considers it impossible. Meanwhile, the protagonist wants to accept the feelings this high schooler causes in him. During a trip to the aquarium, her mother nearly catches them together, and he gets the first taste of how terrified the girl is of her family life, how much she wishes she could break from it all. The more time he spends with her, the more he wants to help and make her happy, putting this girl above caring for his own daughter. Unfortunately, as the daughter suspects, she asks them separately about whether they know each other and are meeting behind her back. They decide to lie, therefore taking a step they can’t take back.

The daughter finds her classes mostly overwhelming, being very introverted, but she manages to make a friend: some delinquent looking guy who is however very kind to her. Meanwhile, his father went from being consider an ace at work to a guy who could barely be relied on to arrive to a meeting in time or pay attention. The high schooler coprotagonist shows the danger she poses to the protagonist’s entire life by planning an afternoon at the protagonist’s house, partly wanting to spend time with his daughter as an excuse. She doesn’t seem to have any malice, but she doesn’t need to. Merely wanting to pursue whatever makes her heart race, which seems to be her main goal, can wreck the protagonist’s entire life.

The guy’s daughter suspects enough about her father and best friend that she confides in her half-delinquent friend, and the guy proposes that they go visit the coffee shop her friend works at, to figure out if they met that evening. All main characters, along with a young, female coworker of the protagonist he had met along the way, confront each other in front of the coffee shop, and the high schooler admits that she loves the protagonist and that they had been meeting each other behind their backs. The daughter flies into a rage and slaps her friend. The protagonist’s coworker excuses herself, disturbed. The protagonist feels as if his life is about to end. The daughter decides to run away from home for a bit, but she identifies enough with his need to run away from it all and find comfort in that girl’s willingness to love him that the daughter goes back home and at least can stand to be in each other’s presence.

Although initially the protagonist had decided to screw his head on straight and make sure he doesn’t lose his job, he faces that he’s grown to care very much, even love, that girl despite it all. When she messages him again, they meet on the streets and talk about what they mean to each other. We get interesting backstory on the girl’s mental state; she feels like a fish in a tank, and that image came from going to the aquarium with her father some years before; when she spoke about how beautiful the fish looked, her father said that they looked miserable, trapped in such a confined space. She identifies more with her absent father, and has ceased to care about most consequences to her somewhat reckless actions, given that they could potentially free her from what she feels is her set path in life.

The protagonist is forced to go on a work trip along with the young coworker, who is careful not to speak about the scene she witnessed in the turning point of this story, and the high schooler coprotagonist decides to show up at the hotel. At this point of the protagonist's feelings for her, he has little issue about making out with her, but he doesn’t want anyone from work to know she’s there.

The girl’s mother put together the pieces of a letter that her daughter had written to the protagonist but that eventually had decided to tear apart. Realizing that her daughter and this man are in a relationship, and caring little about whether it is consensual, she writes a complaint to his work to warn them that he’s dating a sixteen/seventeen year old and that they should fire such a deviant. He gets into trouble at work and has issues denying the allegations; in addition, whenever his young coworker decides to speak, he’ll likely get fired. Almost overwhelmed he meets the girl in a public park to open up about the situation with her mother. He wants to help her break free from her miserable home life, or stand up for herself against her mother at least. She ends up caring little that they are in public, and kisses him, but her mother had followed the girl. She catches them in the act. She attempts to restrain him and makes a huge scene. The police are called. Instead of defending the protagonist, the girl went into a daze and failed to contradict the accusations. So fast it makes the protagonist’s head spin, he is interrogated by two police officers who want to figure out whether he was accosting some underage stranger or whether they have some sort of consensual relationship, which apparently isn’t illegal over there, although it is frowned upon. Once the high schooler admits to a social worker, rather languidly and taking her time, that she loves him, they let them go.

Beginning to realize the damage she has caused by just wanting to be with someone, the girl meets her childhood friend, the daughter of the protagonist. Although the high schooler apologizes and wants to make amends with her friend, the daughter considers her a monster. The high schooler isn’t one to show much emotion; most of the time she seems almost as in a dreamlike state, but it’s clear that having hurt her friend has affected her a lot. Wanting also to run away from her overbearing, controlling mother, she calls the protagonist and apologizes for all the pain she has caused everyone, and that she will take a train and disappear from their lives. The protagonist faces that he’s grown to love this girl and that he wants her in his life, but as he was about to take a taxi to find the girl somehow, his daughter intercepts him. When he explains the situation, his daughter considers that he must have lost his mind, because he can’t seriously consider a relationship with her. She forces him to choose between his daughter or her former friend. To her shock and dismay, he opens up about how much he cares about the girl and that he’s not about to let her run away alone and in pain to who knows where. His daughter is left behind in such a pained state that she vomits.

That’s pretty much as far as this ongoing story has gone. I appreciate the care with which the author has handled some very difficult scenes. She decided to treat this situation as a psychological drama between generally well-meaning people instead of plenty of other routes it could have gone (I would have hated if the girl was treated as a malicious femme fatale type that wanted to ruin his life). The art on display is generally beautiful, with appropriately expressive characters. I’ll add some drawings or even full pages from the mangas.

I'm liking this series very much. Too bad I'll likely forget about it's existence until a year or so from now, and then I'll read around twenty chapters more.

October 23, 2020

Short-lived "vacation"

I must suppose that having a job, even one this unreliable, would be something to celebrate during these times, and in a country ruled by an alliance of socialists and communists who are running the economy straight into the planet's core, but I still feel like throwing it all away and disappearing. I never signed into this being an adult garbage, nor do I want any part of it. I was enjoying that Ikit Claw campaign on TWW2, too.

October 19, 2020

Temporary freedom

I've saved enough money that I don't have to worry in that respect. My biggest concern is what to do with the time. Back in the day, some years ago, I could hardly work a week in an office without feeling as if I was suffocating because my place was hunched over my notebook writing whatever story I had to wring out of myself. Now that I don't feel that psychological need (I retreat into daydreams daily, very elaborate ones, but they are more of the wish fulfillment variety than of the "hero's journey" that would fit a fictional story one could write), reading, watching a few series and browsing the internet, the stuff I could reliably do in my free time while I was working, isn't enough. I've already picked up the guitar again, which I had abandoned in mid july. It has produced blisters in two of my fingertips; it seems that a few months is enough for the previously hardened skin to soften that much.

I've also been looking for elaborate games to lose myself into, but I'm in one of those limbos that occasionally happen in this hobby: although "Crusader Kings 3" is fantastic, I'm waiting for modders to release an alternate history mod that starts in the sixth century, before the Iberian peninsula was invaded by muslims; as I play in my birth province, regaining the lost territory, as a catholic king no less, is a pain. "Total War: Warhammer 2" has had some recent updates that have invalidated significant mods, and it's in one of those unstable states in which you wouldn't want to play without certain mods, but finding the right combination that won't crash your game is very time consuming. I'm hoping that "Cyberpunk 2077" is any good, but it comes out in a few weeks. I'm hoping to buy a next generation VR headset, the HP Reverb G2 in particular (I won't buy the new Oculus, as I hate Facebook's increasingly communistic policies), but it won't begin shipping until early November. I like playing "Project Hospital", which is a realistic simulation of running one, but I'm waiting for a DLC that comes out later this month. Although I could always go to the board games waiting on my shelves, until you get into that groove, the whole process of setting them up and relearning how to play them is a chore.

This afternoon I'm hitting Donostia/San Sebastián, the capital of my province, to buy some guitar strings and just browse some stores at my leisure, which I hadn't found the strength or energies to do since January; while I see that regular people have enough energy to spend when they leave the office, to deal with their family, get together with friends, etc., due to my birth issues just being around people for so many hours a day already squeezes me dry, and every afternoon I had to fight just to stay awake, let alone spend my time doing useful stuff. Likely all this new free time is going to do me some good.

Not much reason to write these words except that I felt like it.

September 5, 2020

Released images generation programs (neuroevolution)

I intended to make a video slideshow with many enlarged images generated with the programs, but turns out that YouTube has turned off that feature. So here are some far fewer images uploaded to a free image hosting site.

September 3, 2020

Moved on to neuroevolution

“Crusader Kings 3”, what seems to me the best game since “The Witcher 3”, lingers in my SSD, as I can’t stop thinking about developing more stuff for this neuroevolution shit. I’ve managed to develop a small program to evolve images.

It isn’t much so far, but it works: the main training program will either spit out a generation of images from zero, or load a previous generation (hopefully rated on their individual merits) and produce the next one. Initially I had to open each json file and write the fitness score manually, but it annoyed me enough that I developed a little program to score them through passing the genome identifier and the score as command line parameters. As soon as I develop a small third program to force manually selected genomes to produce their corresponding image to user defined dimensions, I’ll release them on the GitHub page (which, again, is here).

Neuroevolution works like this: you start by needing the computer to decide on some stuff, anything at all. Might be as small as choosing heads or tails, or deciding on where to invest in the stock market. You always have values gathered from some environment, and what values you decide to pass to the computer is up to you. You need to analyze the environment properly, because you might miss vital aspects that the computer would reasonably need to consider to make an appropriate decision. For my generating images model, I settled on very few input parameters. All we know from the environment is the dimensions of the image the computer has to produce, and the aspects of those dimensions are in this case how far the current pixel is from the extremes of the dimensions (top left, top, top right, left, center, right, bottom left, bottom, bottom right). When the computer is fed those calculated values, for each pixel of the image the computer is queried on what RGBA value to put there. That means that for a 256 x 256 image, the computer needs to be queried 65536 times. Some algorithm should rate the proficiency of that final result, and in this case the algorithm is the brain of the human user. Then, an evolutionary algorithm based on genetic programming crosses over the involved genomes, potentially mutates some aspects of them, and then produces a new population that in the next generation will be queried to produce another set of images.

At the core of this process are, of course, neural networks, the almost magical black boxes to which you pass some values which get altered in the neural network’s black innards, only to get spat out through the other side. The internal composition of the neural network, unless you evolve it through an algorithm like NEAT (which I chose not to get into), is decided by the user. It could have as few as a layer and as few neurons as the outputs the network needs to produce (four in this case, red, green, blue and alpha for each pixel). Potentially it can have hundreds of layers and millions of neurons. At the core of the neural network are neurons: the nodes that receive values either coming from outside of the neural network or from the previous layer. The nodes then apply a magical mathematic thing called an activation function, that transmogrifies the input value to some other. The following image represents some activation functions.

Each node has a single activation function (there might be variations on this I’m not aware of), and each of them produces different visible results on the decision. Whether or not they help will depend on how their decision is rated, and whether they get selected out through evolution.

That’s as much of an explanation as I care to give on the subject. In any case, implementing a neuroevolutionary algorithm almost from scratch on Rust took some shit: I had to get deep into generics and closures, which I had feared dealing with through my previous project. To destroy my fears and out of general obsessive-compulsiveness, I followed the Jurassic Park principle: I was so focused in whether or not I could that I didn’t stop to think if I should. Generics help you use potentially infinite variations of each part involved in a process. In this case I didn’t use any variation: you use a single type of population, genome, neural network, layer and node, and yet I made it so I can expand the system at any point of the future. Any cloner of the repository can do so as well (or should be able to anyway). The cost of that is that the client has to write code like this in main:

Which in turn looks something like this in the corresponding structures (this is all the code for training any population, without the intentions of the client code):

The following are the declarations of the types and such for the controller that deals with training a population:

Pictured: the shocking need to learn algebra.

As I was writing all the generic functions, I wondered where the border between concretion and abstraction was. Generics have no runtime performance penalties in Rust: the compiler turns all generics into concrete implementations during compilation. I struggled to understand how to deal with the inevitable points where you just had to create a concrete class (neurons, populations, neural networks), and there’s no way to create something concrete from generics. The solution ended up being obvious, but it required a different mindset: you need to inject the production of concrete structures into the generic frame. Still, how on Earth would you inject something that produces concretion, when the specific details of whatever you need to construct isn’t known most of the time until the structures need to be created?

The solution is closures. You just pass functions as parameters to the generic core. It was obvious, but it’s such a high level, duck-typing-mindset solution used in languages like Python or Javascript that they seemed impossible to implement in such a hardcore language like Rust. But it’s tremendously easy: the type of a function/closure parameter is something like Fn(u32) -> u32, meaning it receives an unsigned integer and spits out an unsigned integer, and as the value of that parameter you could pass something like |value| { value } (or even without the brackets). That’s it. Value gets passed as a parameter whenever the generic code uses the function, and the client doesn’t need to worry about anything else.

That’s about as much as I can think to write right now. I’ll soon release the programs to evolve images, and I’ll likely play “Crusader Kings 3” for a few days.

August 28, 2020

Mounting stress

It’s friday, got my paycheck (slightly inflated for us in the sort of medical field due to the Corona shit; thank you communists), the workday is coming to an end, and for the rest of the day I’ll go back to programming while some YouTube stuff goes on in the background. Good times. “Crusader Kings 3”, seemingly the best strategy game in a long time, and one of the most moddable, will come out in a few days. Things could be much worse, I guess. Certainly have been.

Also this video for no particular reason.

August 24, 2020

Nuking the codebase

Rust forces you to handle programming constructs that in some cases are even absent in other languages: for example, you need to establish who owns each variable, and in order to prevent some of the hardest to solve bugs in other languages, only a single “structure” at a time can be loaned a mutable variable. That limitation pushes you towards functional programming: basing as much of the program as possible in “closures” that don’t produce side effects: immutable stuff goes in, immutable stuff goes out, and inside you don’t write to any file, you don’t manipulate any database. Obviously you cannot program realistic software like that in its entirety, as at some point you need to track permanent changes to variables at least in memory. However, basing your program on a functional architecture seems like the best possible choice in a language that can handle the performance overhead (because some stuff might need to be copied or cloned).

A couple of weeks ago I had hit a dead end programming my software: external, non-deterministic data (such as player input) entered through a mouth, so to speak, and the changes were done in the depths of the program. That meant that many mutable references were diving deeper and deeper into the code, and at some point the necessities of the code demanded I held on to some of them, which I couldn’t do because of the limitations to borrowing mutable references. In addition, the points of mutability to the data were scattered in the depths, which meant that I couldn’t test nor predict how they affected each other. It was obvious that I needed to refactor most of the program to a functional architecture, but in the end it was easier to learn the lesson and start from scratch. Now the program has gatekeepers (called controllers in a functional architecture) that hold mutable references, and that do as little of the thinking as possible. The decisions are made by structures further into the program, but they don’t get ideally any mutable reference: they just return back to the controllers whatever they decided. That means that the controllers receive a batch of mutations that they, or other controllers, can process sequentially in the outskirts of the program.

Deciding what will change and how, and when and how those changes are implemented, is completely separated in a functional architecture. You end up with abstractions such as ForcesMutation that holds a troop having been eliminated from a space, for example, but the board doesn’t change until those changes are persisted.

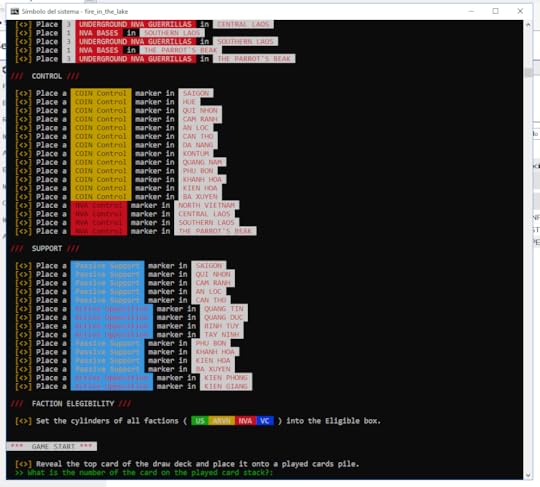

Beyond that, despite being a command line program, I made it look reasonably nice as per the following image:

I’m deep into implementing one of the factions’ bots. There is a suffocating amount of different stuff they can do; just the card events require around 120 individual functions to process their effects (and those are the base functions for the events, not counting all the functions involved in implementing each quantum of their effects). But now that I’ve gained fluidity with the language, it’s just a matter of putting many hours into it.

As usual, the code is available in its github page.

August 12, 2020

Refactoring my “Fire in the Lake” software

Although I had been refactoring bunches of code present in some methods into other methods, and created a couple additional structs when the original structs were handling concerns beyond what they were originally created for, at this point of the project some structs were accumulating massive amounts of methods. Refactoring them would require identifying the general purposes of the methods involved, classifying them and then isolating them from the original code so that area of the codebase wouldn’t be so brittle. I focused first in the area that handles executing the player or bot commands. As a general overview, each of the four players will push through the mouth of the system some words that will relate to their intentions, what they want to do in this turn. If they push through words like “event”, “operation”, “pass”, the system needs to understand that the player wants to play the active card for the event, or wants to perform an operation, or intends to pass. However, we also have words like “6”, “an loc”, “saigon”, “pacify”, “rally”. The system should reliably handle what kind of operation the player wants to play, in what space or spaces of the board, or stuff like how many troops it wants to deploy. In my initial design I simply passed an array of Strings through the command execution system, and those methods had the responsibility to figure out the intention of the player from whatever subset of words the method received. That was a clear violation of the separation of concerns, given that those methods should simply have to focus on executing an operation, a special activity, or delegating declaring that player as having passed, for example.

Before dealing with that major issue, I needed to take some scissors to the execute commands function. The mess of switches and ifs ended up being distributed into isolated functions that handled executing the events, others that executed each kind of operation, others that executed each kind of special activity, another that handled passing, and the biggest group, one that handled atomic executions such as deploying some units somewhere, manipulating the resources of a faction, setting a space to a level of support, improving the trail that the NVA faction uses, etc. That refactorization into a couple dozen files passed the integration tests without much trouble; thankfully, the three almost end-to-end tests that I wrote and that simulated three entire turns of the game are very resistant to refactorization.

There was another section of the code that handled the entirety of the flow of the game: how to deal with the couple of current cards, how to determine what factions were eligible or ineligible, how to slot those factions so that other parts of the system would know that the choices of those factions were already occupied, etc. It ended up being a tremendous chunk of code. I found three major different concerns for the methods involved: some methods just handled the general game flow: setting the active card, informing whether the turn had ended, moving to the next eligible faction according to the order shown in the active card, taking in the general player choices, being able to answer to whoever asked whether the turn had ended or not, etc. Another concern involved handling all the different possibilities for the factions: whether some faction is eligible, whether all are eligible, whether some faction has passed, determining the eligibility of a faction depending on some previous one’s actions, etc. The final concern was related with slotting the factions and moving them around into “holes” that can only hold either one of them at a time or four (maximum number of players). Whether a player has chosen, for example, to perform an operation without a special activity, is very important in this game system, because that means that the following player can only do a limited operation, while if the first player had chosen to play the card’s event, the second player would have been able to do a full operation plus a special activity.

The most pressing concern regarding the following features I had to implement had to do with the fact that I was passing an array of words from the “mouth” of the system to the lowest levels that handled command execution (in some cases to the very lowest level of executing atomic commands). It reeked of primitive envy; what the system should truly know is whether the player intended to perform one of the main choices (passing, event, operation), what operation if the player went that route (ex. rally, train, sweep), whether the player chose to do the additional action allowed for some of the main operations (such as improving the trail), or if the player chose a special activity, which one. We also have the fact that the player might have written the names of spaces (can be cities, provinces or lines of communication), and the program has to figure out if those locations are related to the event, the operation or the special activity. So I refactored out the entirety of that system and created an interpreter that chews the initial commands and just registers the player intentions. It can be asked “does the player want to activate the event?”, which returns a boolean response, and it can be asked to provide the locations associated with the event, for example. Far, far cleaner than the original, system, and not particularly hard to write. It suffers from a case of “excess of switches/ifs”, but it’s not pressing to figure out how to refactor that out. It reads each word as it comes, and depending on what intentions had been “detected”, it will convert to internal enums stuff like the names of places. If it receives the name of a space, the program determines whether, for example, the name actually refers to a space, and in that case if the player had previously sent the word to perform a operation, and in that case if it also had sent the word to perform a special activity. In that case the following spaces would be sent to a list of spaces associated with the special activity, but they would get associated to the operation or the event in other cases.

Again, thanks to the integration tests, the first time I got the major changes to compile, they immediately passed all the tests, so I knew that the previously codified functionality remained intact. That’s the advantage of test driven design: you can dismantle main areas of the code, improve it substantially, and remain confident that everything keeps working as it should. You wouldn’t dare to risk major changes otherwise.

August 10, 2020

Rusty days

The COIN series of games from publisher GMT are maybe the most mechanically complicated and involved board games in the market. Famously designed, originally at least, by an ex-CIA analyst, they feature, usually, four asymmetric factions trying to get ahead in a web of complicated alliances and enmities set during a historical quagmire. For example in their most simple game, "Cuba Libre", that simulates the communist revolution and takeover in Cuba, has you playing as either the government trying to resist the communist horde, or the communists led by Castro, or a student group trying to oppose both the government and the communists, or the American mafia trying to stay in favor of whoever could win, so they can remain in business. Each has its own victory conditions, and at times you might favor a faction over the remainder for purely tactical reasons, just to betray them later. Each turn you draw a card from the "event" deck, which acts as a propagandistic maneuver that can play in your favor if you push for it, but whether to exploit that historical moment or pass (because you can't play the following card, which you can always see, if you play the current one) is where a significant amount of its strategy lies.

Pictured: some of "Fire in the Lake"'s cards.

In addition you can also do many different actions for each faction, such as rallying support, marching through the map, attacking some positions, going underground, recruiting, etc. As I play board games almost exclusively by myself (I don't like being around people, to put it mildly), I would have to command one of those factions and then follow the very complicated flowcharts of each of those simulated opponents in order for them to act. These games are marvelously designed and tremendously engrossing, but having to check each condition of the flowchart and then execute their chosen actions feels too much like work, and takes you out of the fun and involvement of just dealing with your own problems and opportunities. That has a solution, albeit a complicated, time-consuming one: just program your own command line software that can run their logic.

Curt Sellmer did wonders with his software adaptation of Labyrinth (with both its expansions) as well as Colonial Twilight (that simulates the Algerian revolt against the French). In my case, I've never been as interested by a programming language as I've been with Rust since I found out about it; Rust is a blazing fast, memory safe and reliable programming language the likes of which, it seems, had never existed. Amongst programmers it was known that if you wanted the kind of speed that you really need for programming complicated simulations or artificial intelligence stuff (including games), you needed to learn C++, an old and convoluted dinosaur that despite its closeness to machine language, it doesn't save you from inadvertently creating memory holes that will end up popping up as almost unsolvable bugs. Microsoft mentioned how they were moving significant parts of their codebase to Rust, because 70% of the software patches they send out have to do with memory leaks or issues with memory management in general. Rust stops all that; you don't have to allocate the memory yourself, but there's no need, because you do need to establish ownership and lifetimes for all those variables and structures for which the compiler cannot find the obvious declaration (it can deduce most lifetimes, but those it can't more often than not indicate a design problem).

This last few weeks I've been programming like a madman to translate GMT's "Fire in the Lake", about the Vietnam war, into a Rust program. The code is openly available at its GitHub page. I've already cleared most hurdles related to how you need to change your programming mindset regarding Rust's safety model. Some of my habits were related to programming in a garbage collecting language, and they are more often than not impracticable in Rust's environment. For example:

-The biggest hole I fell in had to do, of all things, with a structure that held the parameters, many, that had to be sent to the struct that handles and delegates the decision making of all the factions. It had to be sent the number of the card in play, the faction that had to decide, the full map, all the tracked variables (such as resources, victory markers, etc.), the available forces of all the factions, etc. In any other program you would gather all those parameters into its own class, something like DecideParameters (for the "decide" function), but Rust has a problem with that: you can only ever hold on to a particular mutable reference once. To pass it to some other structure, the structure that held on to that reference has to drop it somehow. The parameter class required plenty of mutable references in its constructor, and it would be doling them out to whoever asked for them. Even though you could program that safely by just making the "decide" function take those references and work with them, you can't really prove that those references held and distributed by the parameter gathering structure wouldn't end up holding a reference to something that had passed away. You can't prove it either in a garbage collected language. The fact that we were doing this is an example of the recklessness that other languages allow; Rust isn't being fastidious by disallowing you to do that: it's just making sure your program can't create those bugs. That means, however, that you are more likely to move on gradually towards a functional style of programming: create structs just when there's some field that really needs to be tracked, and work with functions otherwise. Rust's memory model has no issue with you passing mutable references through functions, as long as they don't stay there somehow, and they can't stay in functions. This limitation does mean, though, that you will end up with parameter lists of potentially 7-10 entries. For example, the only point of entry to the decision making process, the function "decide", looks like this:

fn decide(&self, active_card: u8, current_eligible: Factions, map: &Map, track: &Track, _available_forces: &AvailableForces) -> Decision

-My biggest previous issue with Rust when I looked into it back in 2018 was that you couldn't create collections or in general "group" different structures, even if they implemented the same trait (Rust's more complicated version of other language's interfaces). It's one of the main principles of code quality that you need to program to interfaces instead of to implementations to avoid code coupling, and particularly to isolate volatile and non-deterministic subsystems. That Rust would complain if you were to create a collection of spaces, for example, in which the space in question could be a interface to an implementation of a province, of a city or of a line of communication (as is the case in "Fire in the Lake"), was a tremendous problem without a reliable solution; there's an unsafe way that Rust sort of allows, by creating a dynamic link, but that is 10x slower, handling those references is messy and annoying, and it defeats the purpose of programming in Rust to begin with. However, the community came to the rescue, and there's a fantastic library called enum_dispatch that uses the richer Rust enums to allow a sort of "type identification and grouping" as well as keeping the implemented traits working. It looks like this:

extern crate enum_dispatch;

use self::enum_dispatch::enum_dispatch;

#[enum_dispatch]

pub trait Space {

(...)

}

#[enum_dispatch(Space)]

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum Spaces {

City,

Province,

LineOfCommunication,

}

When instantiating the structs you just have to call the "into" method in order to "transform" them into the enum-like form, but that's all. Otherwise they work as you would expect in any other language.

-In general I've had trouble avoiding some redundancy or close repetition that in other languages you would solve through duck typing or generics. Generics in Rust is a prickly area that I won't dare touch until I'm comfortable enough with the integration tests to make sure there are no regressions.

-Amongst the biggest priorities when attempting to codify a system is figuring out how to isolate the volatile, non-deterministic elements. This game has random input from the dice throws, but much worse is that you have players that are bots and are controlled by complicated flowcharts, but those factions can also be controlled by a human being. At first I considered creating two "paths" through the main system depending on whether a player was a human entering commands with the keyboard or it was a bot, but I found a more elegant solution: to the system, all players behave like humans. The bot's decisions and actions are translated to typed-like commands such as "event", "rally", "operation", or the numerous names of spaces, or the amount of forces it wants to move around. The system that processes those commands and executes them just carries with it a list of commands in an order it can understand, and it doesn't know, nor has any need to know, whether those commands were produced by a human being or a robot. So far I have proved three turns of the playbook that comes with the game, and that's a big deal given how complicated these games are and how many different things the factions can do. For example, this is the code that tests the second turn. I just input the player dummies for the test in the same slots as I would input a regular bot or a human being, and the system doesn't care. Awkwardly, though, I had to store the definitions of the test doubles in the main crate, because num_dispatch doesn't allow the implementations of a trait to be in an extern crate. It just bothers me because of general code quality reasons.

-I'm reading through Vladimir Khorikov's "Unit Testing: Principles, Practices, and Patterns", which seems to be a modern bible on test driven design. I've always been a fanatic of testing first, but I realized as well that while you do need to create a test first, you shouldn't be creating dumb stuff such as whether you can instantiate a struct or access its members: just incorporate whatever struct you create as part of an integration test that proves a system necessity. Through proving the first three turns of the plabook I created many structures and functions, and their behaviors are locked in place, for the most part, through participating in those tests.

I have those familiar itches that make me want to open Visual Studio Code and keep coding as soon as I get home. These obsessions are my particular version of a venereal disease. I hope they last until this small project ends, which shouldn't be that far away.

EDIT: All this talk of testing a program reminds me of one of the biggest legends of gaming, and also the most complicated game ever created, "Dwarf Fortress", that has been going strong for fourteen years and that is gearing up for a Steam release with an updated interface and graphics. Created by a mathematician, he learned programming through writing the game in its initial states, and he readily admitted that his code was probably disastrously structured. I always wished to take a peek at that mountain of code, although it also terrifies me. That game kept piling up features without being able to solve huge bugs that it had introduced years ago, and likely because they cannot be solved at this stage. I doubt their codebase includes any test, so the only safeguard against regressions is whether or not the code compiles when you make a change. That makes me shudder. Still, I wish they would use the Steam money, a significant part of it at least, to just get a bunch of systems analists and coders to rebuild the code from scratch. It would be a thing of beauty.