Jon Ureña's Blog, page 3

May 5, 2025

Life update (05/05/2025)

[check out this post on my personal page, where it looks better]

These days, my beloved guitar satisfies my emotional needs. I head to nearby wooded areas to play. This Saturday, I had walked to one of my favorite spots: in front of a huge tree, on a relatively unknown trail. As I was playing through Joanna Newsom’s “Kingfisher,” suddenly I heard someone hollering. I tensed up, but didn’t look up until someone threw his voice at me, interrupting someone who unequivocally was playing an instrument. I raised my gaze to the grotesque sight of a topless gypsy holding a dining room chair over his head. Of course this fucking mongoloid had to talk to me as I was playing the guitar. He asked if I played rumbas. I told him I didn’t know what that was. He then said that it was flamenco. I told him no. Shortly after, he hollered back to someone to following him, then continued on his way, likely to drink and leave the bottles and other litter there. A couple of other people, presumably gypsies although I couldn’t tell, followed in silence. One of them was a young woman. I got the feeling they felt a bit embarrassed. I finished Joanna Newsom’s “Kingfisher” to the best of my abilities, and then packed up my things and left.

People don’t learn from history; a well-known fact. If we did, we would have learned from the fall of the western half of the Roman Empire, and would have realized that some terrible mistakes should never be repeated: first, don’t convert to Christianity. Second, don’t share your civilization with barbarians. You may enjoy diversity on your plate, until someone shits on it, and then the whole plate is ruined. As for me, I’m not remotely a diversity enjoyer: I want everything in its right place.

Anyway, I suspect that such an encounter with one of the locusts of society would have dissuaded me for a while from playing outside, but the very next day, at about half past three in the afternoon, I picked up my guitar and headed to the deeper woods (in the opposite direction from the other woods). First I headed past the Roman foundries (a reminder that we used to be the city of Oiasso), but the place I picked to play, close to the river, obviously interfered sonically with my playing, so I picked up my things and ended up setting up shop on a raised area next to the foundries. I had only come across a pair of women on my way there, so I thought the afternoon would be quite tranquil. However, I found myself playing songs for older couples and families with children, who stopped to record the foundries, and also ventured deeper into the woods. These people were civilized, so the only interruption I got was three tweens clapping at me as they walked past. Guitar-playing impresses girls, I guess.

When I was in middle school, I remember an instance in which I had to read some essay in class, and I was so nervous, as usual, about speaking in public that my hand shook to the extent that you could hear the rustle of the paper I was holding. Now I casually play the guitar in front of strangers. I’m not entirely comfortable in front of people, of course; I never am even in the best of circumstances. But my concern is that someone may mess with me or even attack me. I don’t feel any genuine connection with human beings, so it’s quite similar to how I’d feel if a deer suddenly stopped to listen. I’d also worry that it may flip out and charge at me, offended at some aspect of my playing. Sadly we don’t have deers around.

Well. Five more days to go, and my vacation starts. I’m heading to Barcelona. Not really in the mood for it, but it’s writing-related, so I’ll have to endure through plenty of aspects of that city that no doubt will infuriate me.

These days, my beloved guitar satisfies my emotional needs. I head to nearby wooded areas to play. This Saturday, I had walked to one of my favorite spots: in front of a huge tree, on a relatively unknown trail. As I was playing through Joanna Newsom’s “Kingfisher,” suddenly I heard someone hollering. I tensed up, but didn’t look up until someone threw his voice at me, interrupting someone who unequivocally was playing an instrument. I raised my gaze to the grotesque sight of a topless gypsy holding a dining room chair over his head. Of course this fucking mongoloid had to talk to me as I was playing the guitar. He asked if I played rumbas. I told him I didn’t know what that was. He then said that it was flamenco. I told him no. Shortly after, he hollered back to someone to following him, then continued on his way, likely to drink and leave the bottles and other litter there. A couple of other people, presumably gypsies although I couldn’t tell, followed in silence. One of them was a young woman. I got the feeling they felt a bit embarrassed. I finished Joanna Newsom’s “Kingfisher” to the best of my abilities, and then packed up my things and left.

People don’t learn from history; a well-known fact. If we did, we would have learned from the fall of the western half of the Roman Empire, and would have realized that some terrible mistakes should never be repeated: first, don’t convert to Christianity. Second, don’t share your civilization with barbarians. You may enjoy diversity on your plate, until someone shits on it, and then the whole plate is ruined. As for me, I’m not remotely a diversity enjoyer: I want everything in its right place.

Anyway, I suspect that such an encounter with one of the locusts of society would have dissuaded me for a while from playing outside, but the very next day, at about half past three in the afternoon, I picked up my guitar and headed to the deeper woods (in the opposite direction from the other woods). First I headed past the Roman foundries (a reminder that we used to be the city of Oiasso), but the place I picked to play, close to the river, obviously interfered sonically with my playing, so I picked up my things and ended up setting up shop on a raised area next to the foundries. I had only come across a pair of women on my way there, so I thought the afternoon would be quite tranquil. However, I found myself playing songs for older couples and families with children, who stopped to record the foundries, and also ventured deeper into the woods. These people were civilized, so the only interruption I got was three tweens clapping at me as they walked past. Guitar-playing impresses girls, I guess.

When I was in middle school, I remember an instance in which I had to read some essay in class, and I was so nervous, as usual, about speaking in public that my hand shook to the extent that you could hear the rustle of the paper I was holding. Now I casually play the guitar in front of strangers. I’m not entirely comfortable in front of people, of course; I never am even in the best of circumstances. But my concern is that someone may mess with me or even attack me. I don’t feel any genuine connection with human beings, so it’s quite similar to how I’d feel if a deer suddenly stopped to listen. I’d also worry that it may flip out and charge at me, offended at some aspect of my playing. Sadly we don’t have deers around.

Well. Five more days to go, and my vacation starts. I’m heading to Barcelona. Not really in the mood for it, but it’s writing-related, so I’ll have to endure through plenty of aspects of that city that no doubt will infuriate me.

Published on May 05, 2025 03:23

•

Tags:

blog, blogging, guitar, life, music, non-fiction, nonfiction, slice-of-life, writing

May 1, 2025

Life update (05/02/2025)

[check out this post on my personal page, where it looks better]

This morning I woke up rattled from a nightmare. I suppose most people’s nightmares involve being physically attacked or pursued, but in my case, my worst nightmares are about ceasing to understand. As far as I remember, most of last night’s dream was like that, but the part I remember the most involved a meeting with my boss and two other coworkers. I wasn’t able to follow their conversation, nor couldn’t understand my boss’ icy attitude toward me. Then he asked me something about a suitcase (that may have been an expression, but the details have slipped through my fingers). I sat there trying to comprehend what he was asking, while my coworkers and my boss looked at me with a mix of disappointment and irritation. I asked, “What does that mean?” My boss looked pissed at my stupidity or ineptitude. Then he asked me if I had done the “context packet,” or something similar. I said that I had no clue what he was talking about. He became irate toward me. When I tried to defend myself, without getting particularly agitated, I was accused of being unable to control myself.

As usual, a mere recounting of a dream doesn’t properly transmit the experience, that of sitting there in that dream office trying my best to understand what was being demanded of me, and yet failing to do so. That’s not far from my every day experience living in the world as an autistic man. In fact, most meetings serve as reminders that my brain doesn’t work like other people’s, as most of the exchanges feel like non-sequiturs to me. I’m usually waiting for the part when someone specifies what needs to be done.

It doesn’t help that I have experienced such moments of my brain failing to comprehend the world, mainly through my experience with migraines. I’m still not convinced that my last one wasn’t a mini-stroke. Back in April of last year, my then boss put me in charge of organizing the replacement of about nine hundred printers throughout the hospital complex where I work. It was a fucking nightmare. Near the end of it, during a day in which I was also hit in the balls by the careless Gen Z worker I had to deal with at the time (he told me a couple of times how eager he was to get back home and play some more Fortnite), I suffered a hemiplegic migraine: suddenly, I started having trouble understanding what I was looking at. Then I smelled something like burnt dust. The right half of my face, and then my right arm to my fingertips, went numb. I ended up in the ER. Three weeks or so later I had an MRI done, but they discarded brain damage. However, I’ve read online that some strokes don’t show up on an MRI. I’ve experienced trouble writing coherently: I sometimes skip letters or mix them up, but I’m not sure if that wasn’t happening beforehand. Maybe it’s just part of the general decay. In any case, one of my biggest fears is suffering a stroke that renders me incapable.

I turned forty about a week ago, and that made me think back to my experience with people over the decades. Growing as a human for me has meant becoming increasingly aware of how much my brain lacks when it comes to social processing. I see myself back as a child, hunched over and drawing because I couldn’t relate to anyone around me, and couldn’t even keep a conversation going for a minute without feeling lost. Of course, when I became a teenager, the problems grew tenfold. My intimate relationships always ended up hurting others as well as me. And I lack the sense of connection with human beings that is generally referred to as “empathy,” so it would be unfair for me to try to get close to others, which in the past I’ve done mostly for curiosity or for writing-related purposes. I do fantasize about intimacy, and I don’t mean just sex, but I guess I’ll have to wait for reincarnation, or incarnated AIs.

Not much else to say beyond these semi-random thoughts. I’ve been busy programming my platform for text-based immersive sims, which is a challenge I’m eager to tackle every day. Whenever I go outside, it’s almost exclusively to delve into a wooded area and play my beloved guitar. If you’re into playing string instruments, you know how much your calloused fingers yearn to return to those strings, to immerse yourself in the emotions captured in the songs, each a unique spell. Playing through Joanna Newsom’s “Kingfisher,” for example, puts me in a trance that snatches me away from this lackluster world into a better place full of meaning.

The wooded area I head to most times is almost unknown, located by the side of an incline road heading into the hilly depths of the province; in the Basque Country, the moment you start heading uphill, it’s like going back in time, and you’re bound to come across very few people, if any at all. The last four or five times I went to play at my usual spot, I only saw one person, and he freaked out when he suddenly noticed a guy sitting there in silence with a guitar (I was about to start playing a song).

Anyway, only six days of work to go, and then I’ll enjoy two weeks of vacation. I hope that along the way, I manage to snatch my one-track mind back to writing; the longer I stay away from it, the more unhinged I feel.

This morning I woke up rattled from a nightmare. I suppose most people’s nightmares involve being physically attacked or pursued, but in my case, my worst nightmares are about ceasing to understand. As far as I remember, most of last night’s dream was like that, but the part I remember the most involved a meeting with my boss and two other coworkers. I wasn’t able to follow their conversation, nor couldn’t understand my boss’ icy attitude toward me. Then he asked me something about a suitcase (that may have been an expression, but the details have slipped through my fingers). I sat there trying to comprehend what he was asking, while my coworkers and my boss looked at me with a mix of disappointment and irritation. I asked, “What does that mean?” My boss looked pissed at my stupidity or ineptitude. Then he asked me if I had done the “context packet,” or something similar. I said that I had no clue what he was talking about. He became irate toward me. When I tried to defend myself, without getting particularly agitated, I was accused of being unable to control myself.

As usual, a mere recounting of a dream doesn’t properly transmit the experience, that of sitting there in that dream office trying my best to understand what was being demanded of me, and yet failing to do so. That’s not far from my every day experience living in the world as an autistic man. In fact, most meetings serve as reminders that my brain doesn’t work like other people’s, as most of the exchanges feel like non-sequiturs to me. I’m usually waiting for the part when someone specifies what needs to be done.

It doesn’t help that I have experienced such moments of my brain failing to comprehend the world, mainly through my experience with migraines. I’m still not convinced that my last one wasn’t a mini-stroke. Back in April of last year, my then boss put me in charge of organizing the replacement of about nine hundred printers throughout the hospital complex where I work. It was a fucking nightmare. Near the end of it, during a day in which I was also hit in the balls by the careless Gen Z worker I had to deal with at the time (he told me a couple of times how eager he was to get back home and play some more Fortnite), I suffered a hemiplegic migraine: suddenly, I started having trouble understanding what I was looking at. Then I smelled something like burnt dust. The right half of my face, and then my right arm to my fingertips, went numb. I ended up in the ER. Three weeks or so later I had an MRI done, but they discarded brain damage. However, I’ve read online that some strokes don’t show up on an MRI. I’ve experienced trouble writing coherently: I sometimes skip letters or mix them up, but I’m not sure if that wasn’t happening beforehand. Maybe it’s just part of the general decay. In any case, one of my biggest fears is suffering a stroke that renders me incapable.

I turned forty about a week ago, and that made me think back to my experience with people over the decades. Growing as a human for me has meant becoming increasingly aware of how much my brain lacks when it comes to social processing. I see myself back as a child, hunched over and drawing because I couldn’t relate to anyone around me, and couldn’t even keep a conversation going for a minute without feeling lost. Of course, when I became a teenager, the problems grew tenfold. My intimate relationships always ended up hurting others as well as me. And I lack the sense of connection with human beings that is generally referred to as “empathy,” so it would be unfair for me to try to get close to others, which in the past I’ve done mostly for curiosity or for writing-related purposes. I do fantasize about intimacy, and I don’t mean just sex, but I guess I’ll have to wait for reincarnation, or incarnated AIs.

Not much else to say beyond these semi-random thoughts. I’ve been busy programming my platform for text-based immersive sims, which is a challenge I’m eager to tackle every day. Whenever I go outside, it’s almost exclusively to delve into a wooded area and play my beloved guitar. If you’re into playing string instruments, you know how much your calloused fingers yearn to return to those strings, to immerse yourself in the emotions captured in the songs, each a unique spell. Playing through Joanna Newsom’s “Kingfisher,” for example, puts me in a trance that snatches me away from this lackluster world into a better place full of meaning.

The wooded area I head to most times is almost unknown, located by the side of an incline road heading into the hilly depths of the province; in the Basque Country, the moment you start heading uphill, it’s like going back in time, and you’re bound to come across very few people, if any at all. The last four or five times I went to play at my usual spot, I only saw one person, and he freaked out when he suddenly noticed a guy sitting there in silence with a guitar (I was about to start playing a song).

Anyway, only six days of work to go, and then I’ll enjoy two weeks of vacation. I hope that along the way, I manage to snatch my one-track mind back to writing; the longer I stay away from it, the more unhinged I feel.

Published on May 01, 2025 23:31

•

Tags:

blog, blogging, health, life, mental-health, non-fiction, nonfiction, slice-of-life, writing

April 29, 2025

Life update (04/29/2025)

[check out this post on my personal page, where it looks better]

I’m now a forty-year-old man, which is one of the things that happen when you turn forty. When I was in my teens, I thought I wouldn’t make it past eighteen. When I hit rock bottom at about twenty-one and I intended to exit this life through the emergency door, I didn’t think I would see that afternoon. And now I have gray hairs in my beard. It hasn’t been a “glad I stuck around” kind of deal; I’m not too happy about being alive.

Anyway, my goal for my forties is to become even more emotionally and physically independent from human beings. My thirties, that included years of working, showed me that all non-necessary interactions with humans, including listening to their grating voices and sounds, as well as their inanity, can literally send me to the ER. I had two episodes of arrhythmia, and then an even scarier hemiplegic migraine, the three of them triggered by stress. Around that time I also experienced a torn retina, although I don’t know to what extent I can fault stress or the health issues I was experiencing at the time. The point is, any extra interaction with humans can ruin me in potentially permanent ways, so to the extent I can get away with, I won’t look people in the eye, and I will wear my noise-canceling headphones to drown out the world’s nonsense. I have to respect my brain’s peculiar needs instead of conceding to other people’s.

Next month I’m going on a trip to Barcelona. The funny thing is that the trip is related to a story I’m writing; I intended to do some research. But I haven’t been writing at all these past couple of weeks due to my sudden obsession with developing a program. I hope to return to it soon enough; I have been feeling my mind deteriorating, becoming increasingly unhinged, which always happens when writing doesn’t ground me. Also, I miss hanging out with Elena.

Speaking of hanging out with non-existing people: I still have daily daydreams about going on time-travel-related adventures with a certain Alicia Western. Most days I don’t even open the ebook reader or my tablet; I just close my eyes and run scenarios in my head. In one of the most recent daydreams, I introduced Alicia to the wonders of augmented reality through a headset made in the 2030s. The headset comes included with an advanced AI named Hypatia, that helps Alicia with her mathematical research.

I don’t know if I intended to say anything else. Barely anyone reads my posts anyway, so this is pure self-expression.

I’m now a forty-year-old man, which is one of the things that happen when you turn forty. When I was in my teens, I thought I wouldn’t make it past eighteen. When I hit rock bottom at about twenty-one and I intended to exit this life through the emergency door, I didn’t think I would see that afternoon. And now I have gray hairs in my beard. It hasn’t been a “glad I stuck around” kind of deal; I’m not too happy about being alive.

Anyway, my goal for my forties is to become even more emotionally and physically independent from human beings. My thirties, that included years of working, showed me that all non-necessary interactions with humans, including listening to their grating voices and sounds, as well as their inanity, can literally send me to the ER. I had two episodes of arrhythmia, and then an even scarier hemiplegic migraine, the three of them triggered by stress. Around that time I also experienced a torn retina, although I don’t know to what extent I can fault stress or the health issues I was experiencing at the time. The point is, any extra interaction with humans can ruin me in potentially permanent ways, so to the extent I can get away with, I won’t look people in the eye, and I will wear my noise-canceling headphones to drown out the world’s nonsense. I have to respect my brain’s peculiar needs instead of conceding to other people’s.

Next month I’m going on a trip to Barcelona. The funny thing is that the trip is related to a story I’m writing; I intended to do some research. But I haven’t been writing at all these past couple of weeks due to my sudden obsession with developing a program. I hope to return to it soon enough; I have been feeling my mind deteriorating, becoming increasingly unhinged, which always happens when writing doesn’t ground me. Also, I miss hanging out with Elena.

Speaking of hanging out with non-existing people: I still have daily daydreams about going on time-travel-related adventures with a certain Alicia Western. Most days I don’t even open the ebook reader or my tablet; I just close my eyes and run scenarios in my head. In one of the most recent daydreams, I introduced Alicia to the wonders of augmented reality through a headset made in the 2030s. The headset comes included with an advanced AI named Hypatia, that helps Alicia with her mathematical research.

I don’t know if I intended to say anything else. Barely anyone reads my posts anyway, so this is pure self-expression.

Published on April 29, 2025 02:21

•

Tags:

blog, blogging, life, non-fiction, nonfiction, slice-of-life, writing

April 23, 2025

Neural Pulse, Pt. 11 (Fiction)

[check out this part on my personal page, where it looks better]

In an electric flash and crackle, my muscles seized, and my vision flared white. As I crumpled backward like a dead weight, my left arm and the side of my head slammed into the control panel. My brain thrummed with electricity. It reeked of burning.

In the whiteness, the silhouette of a spacesuit materialized, looming over me. Several shadows clamped onto my arms with claws. One shadow dug its knees into my abdomen and crushed my face between its palms. I tried to scream, but only a ragged whimper escaped my throat. The tangle of shadows obscured my sight, swallowing me. A shadow snatched my hair and pulled; hundreds of points on my scalp prickled tight. Another shadow smothered my nose and mouth.

When I could feel my arms again, I lashed out at the shadows, thrashing as I braced myself against the control panel and the seat. I lunged for a silhouette—Mara’s spacesuit—but she sidestepped, and I plummeted onto the cockpit floor. A blow to the crown of my head plunged me into a murky confusion.

My wrists were bound behind my back—duct tape, I glimpsed, as Mara, crouched by my knees, finished wrapping my ankles. She straightened and hobbled backward. She stepped on the electroshock lance lying discarded on the floor and slipped, but the oxygen recycler clipped to the back of her suit arrested her fall as it struck the hatch.

Gauges of different shapes bulged on her belt like ammunition magazines. The suit’s chest inflated and deflated rhythmically. Mara unlatched her helmet and pulled it off, revealing her ashen face: mouth agape with baby-pink lips; livid, doubled bags under her eyes; strands of black hair plastered to her forehead with sweat. She leaned back against the hatch, gasping through her mouth, the corners glistening with saliva as she scrutinized me with intense, glazed eyes.

The cockpit reeked of sweat and burnt fuses. The shadows had congealed into a mass of human-shaped silhouettes, their hatred addling my brains, boiling me in a cauldron. Mara’s outline, as if traced with a thick black marker, pulsed and expanded.

No more anticipating how to defend myself, because I have you trapped. Thanks to you, the station doesn’t know we came down to the planet. With the tools of the xenobiologist you murdered, I will rip out your tongue, gouge out your eyes, bore into your face.

Mara crouched, setting her helmet on the floor. Exhaustion contorted her actress-like features, as if some illness burdened her with insomnia and pain.

“I thought I was marooned on this planet. I could have just called the station for rescue, but they’d fire me for nothing, and my pride would rather I suffocated than admit I needed help. Now I know—when we found the artifact, I should have tied you up then. Because you, being you, would just stick your nose right up to an alien machine that, for all you knew, could have detonated the outpost. And to understand what drove you to kill that xenobiologist, I imitated you. I stuck my nose up to that thing, and I saw my reflection. Now I know. Unfortunately, I know.” She regarded me like a comatose patient and waved a gloved palm. “Can you hear me? Did I scramble your brain?”

“I hear.”

My voice emerged as a rasp. I coughed. My mouth tasted of metal.

“And you understand?”

I nodded.

The black veil obscuring the cockpit stirred, rippling. Concentrated energy, like the air crackling before a storm. With Mara’s every gesture, the shadows shifted. Their bony claws crushed my thighs, cinching around my spine through suit, skin, and flesh.

A bead of sweat trickled down Mara’s forehead. She rubbed her face, swallowed. Her pupils constricted.

“Is that what you think? That I’ve convinced myself I’ve subdued you? That you’ll fool me until I let you go? That then you’ll finally strangle me? And even if the station calls it murder, no one will bother investigating, because most people who knew me would thank you for killing me.”

“I’m not thinking. When I try, my brain protests.”

Mara hunched down opposite me, reaching out to study the blow on my head, but halfway there her features pinched. She drew herself up, crossing her arms.

“I heard you telling me to come closer. Because you’ll break free, dig your nails into my corneas, and rip my jaw apart.”

My guts roiled; acid surged up my throat.

“You think I think things like that?”

“I feel this second consciousness… it betrays your thoughts as clearly as if you spoke them aloud. Maybe I’ll never understand how the artifact interfered with our minds, not just our language, but it’s a trick.”

I pushed my torso off the floor, sliding my back up the side of a seat inch by inch, trying not to provoke her, until my stomach settled. My head ached where she’d struck me. The throbbing in my skull clouded and inflamed my thoughts.

“You saw him. Jing. What I did.”

“I saw someone down there. I’d need dental records or DNA to be sure, but I trust elimination. I thought you’d claim it was an accident.”

“It was. I attacked the shadows. You feel them, don’t you?”

Mara took a deep breath.

“They’re pawing at me, trying to suffocate me. Products of my own besieged brain, I know, but I can hardly call them pleasant.”

“I wanted to keep it from affecting you. But at least now you understand.”

“Make no mistake. That xenobiologist is lying with his face beaten to a pulp in the second sublevel of an alien outpost because you are you.”

I pressed my lips together, erecting a wall against escaping words. I looked away from Mara’s eyes, concentrating on deepening my breaths. The muscles in my forearms were taut. Pain flared in my constricted wrists. This woman had fired an electroshock lance at me, beaten me, bound me, and now she was assaulting my character.

With her boot-tip, Mara nudged her helmet; it wobbled like a small boat.

“Although the jolts in my neurons, the shadows, and this other consciousness intruding in my mind unnerve me, the effect isn’t so different from how I’ve always felt around people. The two consciousnesses will learn to get along.”

“If you’re not exaggerating,” I said gravely, “I am truly sorry, Mara.”

She pushed damp strands of hair from her forehead and scrubbed it with the back of her glove, smudging it with dust. The corners of her lips sagged as if weights hung from them.

“Thanks for the sympathy.”

“Were you afraid I planned to do the same thing to you as I did to Jing?”

“Can you blame me for removing the opportunity?”

She limped heavily over to my seat and sat down sideways. As she leaned an elbow on the control panel, a shadow shoved my torso against the seat I leaned on; my lungs emptied. I shuddered, sinking into black water.

Mara had said we imagined the shadows, even if they affected us. I writhed onto my back, pushing with my heels until my head touched the cockpit hatch. My wrists throbbed, crushed tight. A shadow pressed down on my chest like someone sitting there, yet no physical presence had stopped me from moving. The artifact had hijacked my senses.

Mara regarded me from above, pale and cold like a queen enthroned.

“I wouldn’t have killed you,” I said. “You’re my friend.”

“Am I?”

Between the pulses of my headache, I tried to decipher her expression.

“To me, you are.”

“I like you. I tolerate you. But often, being around you feels like rolling in nettles, Kirochka.”

“Almost everything irritates you.”

“You’re incapable of seeing people as anything other than reflections of yourself. What you instinctively feel is right, you impose as right for everyone.” She shook her head, then leaned forward, her tone hardening as if she were tired of holding back. “You insist you have to drag me away from my interests, my studies, as if imitating your actions and hobbies would somehow make me impulsive and reckless too. Admit it or not, you think the rest of humanity are just primitive creatures evolving towards becoming you.” She jabbed a finger at her chest. “I need time to myself, Kirochka. Solitude. Reading. Designing one of my machines, or building it. You think people need to be prevented from thinking.”

Exhaustion was crushing me. I imagined another version of myself laughing, suggesting a drink or a movie, assuming Mara’s mood could be cured by a few laps in the pool. But my vision blurred. I blinked, swallowed to make my vocal cords obey.

“We’ve had good times.”

“The best were when I was enduring idiots and tolerating awful music.”

“You showed them you’re smart. Got half the tracking team to stop calling you ‘black dwarf’.”

“Yes, because those morons’ gossip was costing me sleep. You think I need to prove anything to them? They can believe whatever they want.”

Shadows crouched nearby, focusing their hatred on me, clawing at my skin, crushing my flesh with bony grips. They tormented me like chronic pain, but while Mara and I talked, I kept the torture submerged.

“Things went well for you, for a while, with that man you met. I don’t take credit, but would you have met him dining alone?”

The woman, deflated, blinked her glazed eye, rubbing it as if removing grit.

“You’re right. I miss things by focusing on research instead of acting like a savage. But I assure you, Kirochka, we’re too different for me ever to consider you a friend. Sooner or later, we’d stop tolerating each other.”

“We can bridge the differences.”

“You talk to fill silences. You pressure people for attention. You live for interaction. I could never sustain a friendship with someone like that.”

“Do you use me to get things?”

“Everyone uses everyone, if only to feel better about themselves. I just refrain from feeding illusions.” She drew herself up, as if recalling an injustice, and rebuked me with her eyes. “Besides, I didn’t stop running because I was lazy. I barely eat, and nobody’s chasing me in my apartment. Running bores me to death.”

“I wanted the company.”

Mara shook her head. Her tired gaze roamed the cockpit, as if seeing through the walls.

“When you called a few hours ago, I thought you wanted to drag me out drinking with you and the other pilots. I considered pretending I’d fallen asleep with the sound nullifier on. I should have.”

I contorted like a snake, sliding my back up the hatch. I leaned the oxygen recycler back, resting my head against the cool metal. Judging by the ache, when I undressed, my arms would be covered in lurid bruises.

“I consider you a friend. You listen when I need it. My professional peers, the ones who think they’re my friends, even my boyfriend—they’d tell me to shut up for ruining the mood.”

“When have you ever listened to me?”

“I want to. But I have to pry the words out of you.”

“Maybe that should have told you something, Kirochka.”

“That you hate me.”

She sighed, the effort seeming immense, like lifting a great weight.

“I don’t like human beings. I would have chosen to be anything else.”

Flashes on the communications monitor distracted me. Though Mara was still speaking, her words faded to a murmur beneath my notice. The headache pulsed, reddening my vision. Why did the monitor alert snag my attention? I snapped fully alert. It meant an incoming call.

---

Author’s note: I wrote this novella in Spanish about ten years ago. It’s contained in the collection titled Los dominios del emperador búho.

Today’s song is “Body Betrays Itself” by Pharmakon.

In an electric flash and crackle, my muscles seized, and my vision flared white. As I crumpled backward like a dead weight, my left arm and the side of my head slammed into the control panel. My brain thrummed with electricity. It reeked of burning.

In the whiteness, the silhouette of a spacesuit materialized, looming over me. Several shadows clamped onto my arms with claws. One shadow dug its knees into my abdomen and crushed my face between its palms. I tried to scream, but only a ragged whimper escaped my throat. The tangle of shadows obscured my sight, swallowing me. A shadow snatched my hair and pulled; hundreds of points on my scalp prickled tight. Another shadow smothered my nose and mouth.

When I could feel my arms again, I lashed out at the shadows, thrashing as I braced myself against the control panel and the seat. I lunged for a silhouette—Mara’s spacesuit—but she sidestepped, and I plummeted onto the cockpit floor. A blow to the crown of my head plunged me into a murky confusion.

My wrists were bound behind my back—duct tape, I glimpsed, as Mara, crouched by my knees, finished wrapping my ankles. She straightened and hobbled backward. She stepped on the electroshock lance lying discarded on the floor and slipped, but the oxygen recycler clipped to the back of her suit arrested her fall as it struck the hatch.

Gauges of different shapes bulged on her belt like ammunition magazines. The suit’s chest inflated and deflated rhythmically. Mara unlatched her helmet and pulled it off, revealing her ashen face: mouth agape with baby-pink lips; livid, doubled bags under her eyes; strands of black hair plastered to her forehead with sweat. She leaned back against the hatch, gasping through her mouth, the corners glistening with saliva as she scrutinized me with intense, glazed eyes.

The cockpit reeked of sweat and burnt fuses. The shadows had congealed into a mass of human-shaped silhouettes, their hatred addling my brains, boiling me in a cauldron. Mara’s outline, as if traced with a thick black marker, pulsed and expanded.

No more anticipating how to defend myself, because I have you trapped. Thanks to you, the station doesn’t know we came down to the planet. With the tools of the xenobiologist you murdered, I will rip out your tongue, gouge out your eyes, bore into your face.

Mara crouched, setting her helmet on the floor. Exhaustion contorted her actress-like features, as if some illness burdened her with insomnia and pain.

“I thought I was marooned on this planet. I could have just called the station for rescue, but they’d fire me for nothing, and my pride would rather I suffocated than admit I needed help. Now I know—when we found the artifact, I should have tied you up then. Because you, being you, would just stick your nose right up to an alien machine that, for all you knew, could have detonated the outpost. And to understand what drove you to kill that xenobiologist, I imitated you. I stuck my nose up to that thing, and I saw my reflection. Now I know. Unfortunately, I know.” She regarded me like a comatose patient and waved a gloved palm. “Can you hear me? Did I scramble your brain?”

“I hear.”

My voice emerged as a rasp. I coughed. My mouth tasted of metal.

“And you understand?”

I nodded.

The black veil obscuring the cockpit stirred, rippling. Concentrated energy, like the air crackling before a storm. With Mara’s every gesture, the shadows shifted. Their bony claws crushed my thighs, cinching around my spine through suit, skin, and flesh.

A bead of sweat trickled down Mara’s forehead. She rubbed her face, swallowed. Her pupils constricted.

“Is that what you think? That I’ve convinced myself I’ve subdued you? That you’ll fool me until I let you go? That then you’ll finally strangle me? And even if the station calls it murder, no one will bother investigating, because most people who knew me would thank you for killing me.”

“I’m not thinking. When I try, my brain protests.”

Mara hunched down opposite me, reaching out to study the blow on my head, but halfway there her features pinched. She drew herself up, crossing her arms.

“I heard you telling me to come closer. Because you’ll break free, dig your nails into my corneas, and rip my jaw apart.”

My guts roiled; acid surged up my throat.

“You think I think things like that?”

“I feel this second consciousness… it betrays your thoughts as clearly as if you spoke them aloud. Maybe I’ll never understand how the artifact interfered with our minds, not just our language, but it’s a trick.”

I pushed my torso off the floor, sliding my back up the side of a seat inch by inch, trying not to provoke her, until my stomach settled. My head ached where she’d struck me. The throbbing in my skull clouded and inflamed my thoughts.

“You saw him. Jing. What I did.”

“I saw someone down there. I’d need dental records or DNA to be sure, but I trust elimination. I thought you’d claim it was an accident.”

“It was. I attacked the shadows. You feel them, don’t you?”

Mara took a deep breath.

“They’re pawing at me, trying to suffocate me. Products of my own besieged brain, I know, but I can hardly call them pleasant.”

“I wanted to keep it from affecting you. But at least now you understand.”

“Make no mistake. That xenobiologist is lying with his face beaten to a pulp in the second sublevel of an alien outpost because you are you.”

I pressed my lips together, erecting a wall against escaping words. I looked away from Mara’s eyes, concentrating on deepening my breaths. The muscles in my forearms were taut. Pain flared in my constricted wrists. This woman had fired an electroshock lance at me, beaten me, bound me, and now she was assaulting my character.

With her boot-tip, Mara nudged her helmet; it wobbled like a small boat.

“Although the jolts in my neurons, the shadows, and this other consciousness intruding in my mind unnerve me, the effect isn’t so different from how I’ve always felt around people. The two consciousnesses will learn to get along.”

“If you’re not exaggerating,” I said gravely, “I am truly sorry, Mara.”

She pushed damp strands of hair from her forehead and scrubbed it with the back of her glove, smudging it with dust. The corners of her lips sagged as if weights hung from them.

“Thanks for the sympathy.”

“Were you afraid I planned to do the same thing to you as I did to Jing?”

“Can you blame me for removing the opportunity?”

She limped heavily over to my seat and sat down sideways. As she leaned an elbow on the control panel, a shadow shoved my torso against the seat I leaned on; my lungs emptied. I shuddered, sinking into black water.

Mara had said we imagined the shadows, even if they affected us. I writhed onto my back, pushing with my heels until my head touched the cockpit hatch. My wrists throbbed, crushed tight. A shadow pressed down on my chest like someone sitting there, yet no physical presence had stopped me from moving. The artifact had hijacked my senses.

Mara regarded me from above, pale and cold like a queen enthroned.

“I wouldn’t have killed you,” I said. “You’re my friend.”

“Am I?”

Between the pulses of my headache, I tried to decipher her expression.

“To me, you are.”

“I like you. I tolerate you. But often, being around you feels like rolling in nettles, Kirochka.”

“Almost everything irritates you.”

“You’re incapable of seeing people as anything other than reflections of yourself. What you instinctively feel is right, you impose as right for everyone.” She shook her head, then leaned forward, her tone hardening as if she were tired of holding back. “You insist you have to drag me away from my interests, my studies, as if imitating your actions and hobbies would somehow make me impulsive and reckless too. Admit it or not, you think the rest of humanity are just primitive creatures evolving towards becoming you.” She jabbed a finger at her chest. “I need time to myself, Kirochka. Solitude. Reading. Designing one of my machines, or building it. You think people need to be prevented from thinking.”

Exhaustion was crushing me. I imagined another version of myself laughing, suggesting a drink or a movie, assuming Mara’s mood could be cured by a few laps in the pool. But my vision blurred. I blinked, swallowed to make my vocal cords obey.

“We’ve had good times.”

“The best were when I was enduring idiots and tolerating awful music.”

“You showed them you’re smart. Got half the tracking team to stop calling you ‘black dwarf’.”

“Yes, because those morons’ gossip was costing me sleep. You think I need to prove anything to them? They can believe whatever they want.”

Shadows crouched nearby, focusing their hatred on me, clawing at my skin, crushing my flesh with bony grips. They tormented me like chronic pain, but while Mara and I talked, I kept the torture submerged.

“Things went well for you, for a while, with that man you met. I don’t take credit, but would you have met him dining alone?”

The woman, deflated, blinked her glazed eye, rubbing it as if removing grit.

“You’re right. I miss things by focusing on research instead of acting like a savage. But I assure you, Kirochka, we’re too different for me ever to consider you a friend. Sooner or later, we’d stop tolerating each other.”

“We can bridge the differences.”

“You talk to fill silences. You pressure people for attention. You live for interaction. I could never sustain a friendship with someone like that.”

“Do you use me to get things?”

“Everyone uses everyone, if only to feel better about themselves. I just refrain from feeding illusions.” She drew herself up, as if recalling an injustice, and rebuked me with her eyes. “Besides, I didn’t stop running because I was lazy. I barely eat, and nobody’s chasing me in my apartment. Running bores me to death.”

“I wanted the company.”

Mara shook her head. Her tired gaze roamed the cockpit, as if seeing through the walls.

“When you called a few hours ago, I thought you wanted to drag me out drinking with you and the other pilots. I considered pretending I’d fallen asleep with the sound nullifier on. I should have.”

I contorted like a snake, sliding my back up the hatch. I leaned the oxygen recycler back, resting my head against the cool metal. Judging by the ache, when I undressed, my arms would be covered in lurid bruises.

“I consider you a friend. You listen when I need it. My professional peers, the ones who think they’re my friends, even my boyfriend—they’d tell me to shut up for ruining the mood.”

“When have you ever listened to me?”

“I want to. But I have to pry the words out of you.”

“Maybe that should have told you something, Kirochka.”

“That you hate me.”

She sighed, the effort seeming immense, like lifting a great weight.

“I don’t like human beings. I would have chosen to be anything else.”

Flashes on the communications monitor distracted me. Though Mara was still speaking, her words faded to a murmur beneath my notice. The headache pulsed, reddening my vision. Why did the monitor alert snag my attention? I snapped fully alert. It meant an incoming call.

---

Author’s note: I wrote this novella in Spanish about ten years ago. It’s contained in the collection titled Los dominios del emperador búho.

Today’s song is “Body Betrays Itself” by Pharmakon.

Published on April 23, 2025 04:54

•

Tags:

art, book, books, creative-writing, fiction, novella, novellas, scene, short-fiction, short-stories, short-story, writing

April 18, 2025

Living Narrative Engine, #1

[check out this post on my personal page, where it looks better]

This past week I’ve been in my equivalent of a drug binge. Out of nowhere, I became obsessed with the notion of implementing a text-based immersive sim relying on “vibe coding,” as has come to be known the extremely powerful approach of relying on very competent large-language models to code virtually everything in your app. Once I tasted Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro’s power, I fell in love. The few times it makes mistakes, it’s usually my fault for not expressing my requirements correctly. Curiously enough, OpenAI released a more powerful model just a couple of days ago: o3. Sadly it’s under usage limits.

Anyway, let me explain about the project, named Living Narrative Engine. You can clone the repository from its GitHub page.

It’s a browser-based engine to play text adventures. My intention was to make it as moddable and data-driven as possible, to the extent that one could define actions in JSON files, indicating prerequisites for the action, the domain of applicability, what events it would fire on completion, etc, and the action-agnostic code would just run with it. I mention the actions because that’s the last part of the core of this app that I’m about to delve into; currently actions such as “look”, “hit”, “move”, “unlock” and such are harcoded in the system: each has a dedicated action handler. That’s terrible for the purposes of making it data-driven, so I’ve requested deep-search research documents and product requirement documents from ChatGPT, which look hella good. Before I start tearing apart the action system of the app, which may take a couple of days, I wanted to put this working version out there.

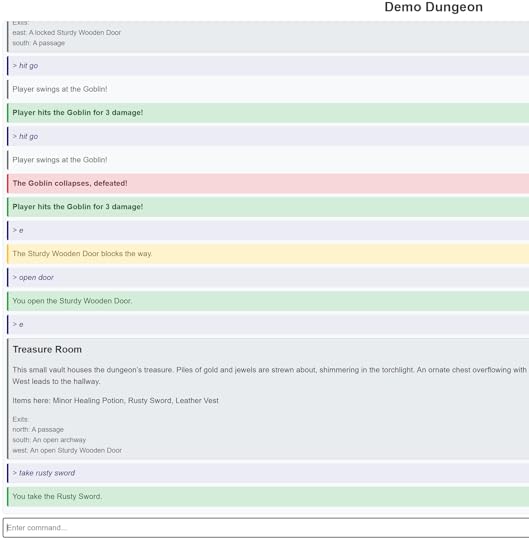

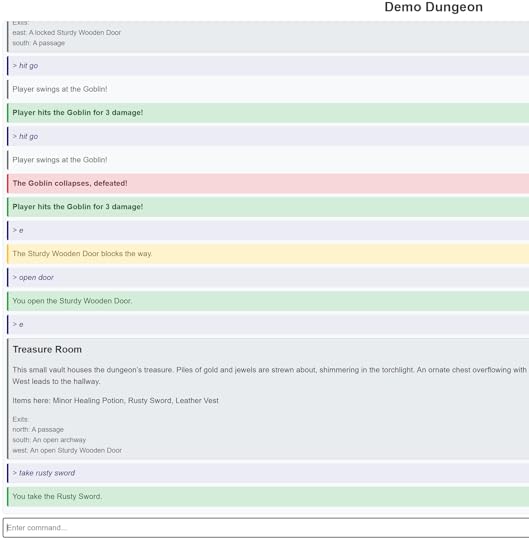

Currently the app does the minimum for a demo: it spawns you in a room, lets you move from room to room, kill a goblin, open doors, take items, equip items (and drop and unequip them), and also unlock doors (which was the hardest part of the app to codify). I have introduced quest and objective systems that listen to conditions; for example, there’s no key in the demo to open the door where the goblin is located, but when the event “event:entity_died” fires with that goblin as the subject, the door opens mysteriously. The single JSON file that drives that is below:

The goal is to make everything as data-driven and agnostic as possible.

Everything in the game world is an entity: an identifier and a bunch of components. For example, if any entity has the Item component, it can be picked up. If it has the Openable component, it can be opened and closed. If it has the Lockable component and also the Openable component, the entity cannot be opened if it’s locked. This leads to fascinating combinations of behavior that change as long as you add or remove components, or change the internal numbers of components.

The biggest hurdle involved figuring out how to represent doors and other passage blockers. All rooms are simple entities with a ConnectionsComponent. The ConnectionsComponent indicates possible exits. Initially the user could only interact with entities with a PositionComponent pointing to the user’s room, but doors aren’t quite in one room, are they? They’re at the threshold of two rooms. So I had to write special code to target them.

Anyway, this is way too much fun. Sadly for the writing aspect of my self, I haven’t written anything in about five days. I’ll return to it shortly, for sure; these binges of mine tend to burn out by themselves.

My near-future goal of this app is to involve large-language models. I want to populate rooms with sentient AIs, given them a list of valid options to choose from regarding their surroundings (such as “move north”, “eat cheesecake”, or “kick baboon”), and have them choose according to their written-in personalities. I want to find myself playing through RPG, text-based campaigns along with a harem of AI-controlled isekai hotties.

I’m going back to it. See ya.

This past week I’ve been in my equivalent of a drug binge. Out of nowhere, I became obsessed with the notion of implementing a text-based immersive sim relying on “vibe coding,” as has come to be known the extremely powerful approach of relying on very competent large-language models to code virtually everything in your app. Once I tasted Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro’s power, I fell in love. The few times it makes mistakes, it’s usually my fault for not expressing my requirements correctly. Curiously enough, OpenAI released a more powerful model just a couple of days ago: o3. Sadly it’s under usage limits.

Anyway, let me explain about the project, named Living Narrative Engine. You can clone the repository from its GitHub page.

It’s a browser-based engine to play text adventures. My intention was to make it as moddable and data-driven as possible, to the extent that one could define actions in JSON files, indicating prerequisites for the action, the domain of applicability, what events it would fire on completion, etc, and the action-agnostic code would just run with it. I mention the actions because that’s the last part of the core of this app that I’m about to delve into; currently actions such as “look”, “hit”, “move”, “unlock” and such are harcoded in the system: each has a dedicated action handler. That’s terrible for the purposes of making it data-driven, so I’ve requested deep-search research documents and product requirement documents from ChatGPT, which look hella good. Before I start tearing apart the action system of the app, which may take a couple of days, I wanted to put this working version out there.

Currently the app does the minimum for a demo: it spawns you in a room, lets you move from room to room, kill a goblin, open doors, take items, equip items (and drop and unequip them), and also unlock doors (which was the hardest part of the app to codify). I have introduced quest and objective systems that listen to conditions; for example, there’s no key in the demo to open the door where the goblin is located, but when the event “event:entity_died” fires with that goblin as the subject, the door opens mysteriously. The single JSON file that drives that is below:

{

"id": "demo:trigger_unlock_treasure_door_on_goblin_death",

"listen_to": {

"event_type": "event:entity_died",

"filters": {

"deceasedEntityId": "demo:enemy_goblin"

}

},

"effects": [

{

"type": "trigger_event",

"parameters": {

"eventName": "event:unlock_entity_force",

"payload": {

"targetEntityId": "demo:door_treasure_room"

}

}

}

],

"one_shot": true

}

The goal is to make everything as data-driven and agnostic as possible.

Everything in the game world is an entity: an identifier and a bunch of components. For example, if any entity has the Item component, it can be picked up. If it has the Openable component, it can be opened and closed. If it has the Lockable component and also the Openable component, the entity cannot be opened if it’s locked. This leads to fascinating combinations of behavior that change as long as you add or remove components, or change the internal numbers of components.

The biggest hurdle involved figuring out how to represent doors and other passage blockers. All rooms are simple entities with a ConnectionsComponent. The ConnectionsComponent indicates possible exits. Initially the user could only interact with entities with a PositionComponent pointing to the user’s room, but doors aren’t quite in one room, are they? They’re at the threshold of two rooms. So I had to write special code to target them.

Anyway, this is way too much fun. Sadly for the writing aspect of my self, I haven’t written anything in about five days. I’ll return to it shortly, for sure; these binges of mine tend to burn out by themselves.

My near-future goal of this app is to involve large-language models. I want to populate rooms with sentient AIs, given them a list of valid options to choose from regarding their surroundings (such as “move north”, “eat cheesecake”, or “kick baboon”), and have them choose according to their written-in personalities. I want to find myself playing through RPG, text-based campaigns along with a harem of AI-controlled isekai hotties.

I’m going back to it. See ya.

Published on April 18, 2025 09:20

•

Tags:

ai, artificial-intelligence, gaming, javascript, llm, llms, programming, technology

April 10, 2025

Neural Pulse, Pt. 10 (Fiction)

[check out this part on my personal page, where it looks better]

Paralyzed, I choked. I sucked in a lungful of hot air and collapsed to my knees before the xenobiologist. I pressed my hands against his suit’s chest. I pounded on him. No one would recognize Jing from what was left of his blood-drenched face. I stammered, repeating, “no, no, no,” while my fingers traced the helmet’s dents, the jagged shards of the broken visor jutting from the frame.

Pooling blood submerged the ruin of bone and flesh that was his face. When I tilted Jing’s body, the helmet spilled a tongue of blood onto the stone floor, slick with sliding globules of brain matter.

I staggered back, fists clenched, shuddering violently as if seized by frost.

Jing’s right hand was clamped around the handle of an automatic core drill. Perhaps the xenobiologist had approached to help me.

I shut my eyes, covered my visor with a palm. I pictured Jing standing beside me, an echo asking if I needed help. No, I hadn’t killed him. When I opened my eyes, the corpse lay sprawled on its side, the dented helmet cradling the ruin of his head.

Jing hadn’t known he was dealing with a live nuclear device. The flood of that feeling had swept over me. Had I seen the xenobiologist stop beside me? Had I decided to smash his face in with the crowbar?

I stumbled about, gasping for breath. My brain felt like it was on fire, seizing with electric spasms. Red webs pulsed at the edges of my vision, flaring brightly before fading. Before I knew it, I’d crossed the room that contained the construction robots, and was sprinting up the ramp. The oval beam of my flashlight jerked and warped, sliding over the protrusions and crevices of the rock face. My arms felt like spent rubber bands, especially the right, aching from fingertips to shoulder blades. Every balancing lurch, every push against the rock to keep climbing, intensified the ache.

I passed the first sublevel. My breath fogged the visor; I saw the flashlight beam dimly, as through a mist. My hair, pulled back at my nape, was soaked through, plastered to my skin.

I burst onto the surface, into the emptiness of the dome. I staggered, kicking through the sandy earth. I gasped for air and ran. I pictured myself training on a circuit—something that relaxed me at the academy after piloting, just as going to the gym with Mara relaxed me on the station—but now I was running from the consequences, from an earthquake tearing the earth apart like cloth. If I slowed, the fissure would overtake and swallow me.

I vaulted over the embankment to the left of the esplanade, where I’d hidden before, landing on my knees and one forearm. I scrambled backward, kicking up dirt, and pressed myself flat against the embankment’s exposed rock face.

The radio. I navigated the visor options until I muted my comm signal. When the notification confirmed I was off-frequency, I jammed my fists against my knees, my mouth stretched wide in a scream.

I drew a ragged breath. Beads of sweat dripped from my forehead onto the visor; the material wicked them away, like water hitting hot pavement. Mara would have reached the cockpit by now, found me missing. Nothing could make Jing’s death look like an accident. How would my friend look at me? What would she think when she found out? She’d think… because I killed the xenobiologist… I might kill her too.

I buried my helmeted head in my forearms. I welcomed the dimness. How had I let this happen? I knew I should have destroyed the artifact—just as I knew I had to fight back when those shadows grabbed me, tried to rip me open with their claws. I’d struck the shadows with the crowbar before I’d even consciously decided to. On other expeditions, while waiting for scientists and soldiers to emerge from some dense alien jungle, I’d monitor their radio chatter, trusting my instincts to warn me if I should suggest aborting the mission. Just as piloting was like flowing in a dance of thrust and gravity, the way dancing came naturally to others, I imagined. Now my instincts screamed at me to flee, to run from this embankment away from the ship, to strike out across the planet, heedless of survival. My instinct had been supplanted by another. And I knew the difference.

I peeked around the side of the embankment. The scarred esplanade remained deserted. The crystalline dome watched the minutes pass like some ancient ruin.

If Mara found out the artifact made me kill Jing, maybe she’d understand the danger, agree to destroy it. I was counting on her reasoning, on that cold logic that had so often irritated me. But if I waited too long to face her, she’d suspect my motives.

As I straightened up and stepped, dizzy, onto the esplanade, an electric spike lanced through my neurons, blurring my vision. I stumbled around until it subsided. I stopped before the central crater, hunching over to examine its charcoal-gray cracks and ridges. Crushed bones.

I activated the radio. The visor display indicated it was locking onto Mara’s signal. She’d see mine pop up, too, unless she was distracted. In the center of my darkened visor, the arctic-blue star shone through the thin atmosphere like a quivering ball of fluff.

“Where are you, Mara?”

“Cockpit.”

The shadows intercepted the transmission, projecting their hatred at me. It distracted me from Mara’s tone—was there suspicion coloring her voice? I waited a few seconds. Would she demand an explanation? Why was she silent?

“Good,” I said. “Stay there. I need to talk to you.”

As I climbed the slope skirting the hill towards the ship, the reality of my decision hit me. I was about to lock myself in the cockpit’s confined space with Mara. Her shadows would envelop me, sink their claws into my skin, force themselves down my throat to suffocate me. I wanted desperately to rip off my helmet, wipe the sweat from my face. I needed a shower, a moment to think.

I located the ship’s tower. Several meters ahead lay three cargo containers and scattered tools. Inside the cargo hold, chunks of the robots and the materializer were heaped like scrap in a landfill.

I scrambled up the boarding ladder to the airlock hatch. Opened it, scrambled inside, sealed it shut. The chamber pressurized with a series of hisses and puffs. I unsealed my helmet. Holding it upside down, steam poured out as if from a pot of fresh soup. I gulped the ship’s cool, filtered air and opened the inner door to the cockpit.

“Mara.”

Empty. Indicators blinked. On the monitors, ship status displays and sector topographical maps cycled. Lines of text scrolled.

My seat held a roll of electrical tape. As I turned it over in my fingers, an electric jolt made me clench my teeth, squeeze my eyes shut. My neurons hummed.

The door to the airlock chamber clicked shut with a heavy mechanical thud. The thick metal muffled the hissing. Leaning back against my seat’s headrest, still clutching the tape, I froze. The air grew heavy. The cockpit lights seemed to dim, the edges of my perception closing in. A dozen shadows waited in the airlock chamber, their concentrated beams of hatred probing the metal door, seeking to burn me.

The door slid open.

I tensed, lips parting. What could I possibly say?

Mara emerged sideways through the gap, head bowed. As she stepped through, she shouldered the door shut behind her. The glowing diodes and bright screens of the control panel glinted on her helmet’s visor. She whipped around to face me. Her right arm shot out, leveling an electroshock lance. The two silver prongs at its tip lunged like viper fangs.

-----

Author’s note: I originally wrote this novella in Spanish about ten years ago. It’s contained in the collection titled Los dominios del emperador búho.

Paralyzed, I choked. I sucked in a lungful of hot air and collapsed to my knees before the xenobiologist. I pressed my hands against his suit’s chest. I pounded on him. No one would recognize Jing from what was left of his blood-drenched face. I stammered, repeating, “no, no, no,” while my fingers traced the helmet’s dents, the jagged shards of the broken visor jutting from the frame.

Pooling blood submerged the ruin of bone and flesh that was his face. When I tilted Jing’s body, the helmet spilled a tongue of blood onto the stone floor, slick with sliding globules of brain matter.

I staggered back, fists clenched, shuddering violently as if seized by frost.

Jing’s right hand was clamped around the handle of an automatic core drill. Perhaps the xenobiologist had approached to help me.

I shut my eyes, covered my visor with a palm. I pictured Jing standing beside me, an echo asking if I needed help. No, I hadn’t killed him. When I opened my eyes, the corpse lay sprawled on its side, the dented helmet cradling the ruin of his head.

Jing hadn’t known he was dealing with a live nuclear device. The flood of that feeling had swept over me. Had I seen the xenobiologist stop beside me? Had I decided to smash his face in with the crowbar?

I stumbled about, gasping for breath. My brain felt like it was on fire, seizing with electric spasms. Red webs pulsed at the edges of my vision, flaring brightly before fading. Before I knew it, I’d crossed the room that contained the construction robots, and was sprinting up the ramp. The oval beam of my flashlight jerked and warped, sliding over the protrusions and crevices of the rock face. My arms felt like spent rubber bands, especially the right, aching from fingertips to shoulder blades. Every balancing lurch, every push against the rock to keep climbing, intensified the ache.

I passed the first sublevel. My breath fogged the visor; I saw the flashlight beam dimly, as through a mist. My hair, pulled back at my nape, was soaked through, plastered to my skin.

I burst onto the surface, into the emptiness of the dome. I staggered, kicking through the sandy earth. I gasped for air and ran. I pictured myself training on a circuit—something that relaxed me at the academy after piloting, just as going to the gym with Mara relaxed me on the station—but now I was running from the consequences, from an earthquake tearing the earth apart like cloth. If I slowed, the fissure would overtake and swallow me.

I vaulted over the embankment to the left of the esplanade, where I’d hidden before, landing on my knees and one forearm. I scrambled backward, kicking up dirt, and pressed myself flat against the embankment’s exposed rock face.

The radio. I navigated the visor options until I muted my comm signal. When the notification confirmed I was off-frequency, I jammed my fists against my knees, my mouth stretched wide in a scream.

I drew a ragged breath. Beads of sweat dripped from my forehead onto the visor; the material wicked them away, like water hitting hot pavement. Mara would have reached the cockpit by now, found me missing. Nothing could make Jing’s death look like an accident. How would my friend look at me? What would she think when she found out? She’d think… because I killed the xenobiologist… I might kill her too.

I buried my helmeted head in my forearms. I welcomed the dimness. How had I let this happen? I knew I should have destroyed the artifact—just as I knew I had to fight back when those shadows grabbed me, tried to rip me open with their claws. I’d struck the shadows with the crowbar before I’d even consciously decided to. On other expeditions, while waiting for scientists and soldiers to emerge from some dense alien jungle, I’d monitor their radio chatter, trusting my instincts to warn me if I should suggest aborting the mission. Just as piloting was like flowing in a dance of thrust and gravity, the way dancing came naturally to others, I imagined. Now my instincts screamed at me to flee, to run from this embankment away from the ship, to strike out across the planet, heedless of survival. My instinct had been supplanted by another. And I knew the difference.

I peeked around the side of the embankment. The scarred esplanade remained deserted. The crystalline dome watched the minutes pass like some ancient ruin.

If Mara found out the artifact made me kill Jing, maybe she’d understand the danger, agree to destroy it. I was counting on her reasoning, on that cold logic that had so often irritated me. But if I waited too long to face her, she’d suspect my motives.

As I straightened up and stepped, dizzy, onto the esplanade, an electric spike lanced through my neurons, blurring my vision. I stumbled around until it subsided. I stopped before the central crater, hunching over to examine its charcoal-gray cracks and ridges. Crushed bones.

I activated the radio. The visor display indicated it was locking onto Mara’s signal. She’d see mine pop up, too, unless she was distracted. In the center of my darkened visor, the arctic-blue star shone through the thin atmosphere like a quivering ball of fluff.

“Where are you, Mara?”

“Cockpit.”

The shadows intercepted the transmission, projecting their hatred at me. It distracted me from Mara’s tone—was there suspicion coloring her voice? I waited a few seconds. Would she demand an explanation? Why was she silent?

“Good,” I said. “Stay there. I need to talk to you.”

As I climbed the slope skirting the hill towards the ship, the reality of my decision hit me. I was about to lock myself in the cockpit’s confined space with Mara. Her shadows would envelop me, sink their claws into my skin, force themselves down my throat to suffocate me. I wanted desperately to rip off my helmet, wipe the sweat from my face. I needed a shower, a moment to think.

I located the ship’s tower. Several meters ahead lay three cargo containers and scattered tools. Inside the cargo hold, chunks of the robots and the materializer were heaped like scrap in a landfill.

I scrambled up the boarding ladder to the airlock hatch. Opened it, scrambled inside, sealed it shut. The chamber pressurized with a series of hisses and puffs. I unsealed my helmet. Holding it upside down, steam poured out as if from a pot of fresh soup. I gulped the ship’s cool, filtered air and opened the inner door to the cockpit.

“Mara.”

Empty. Indicators blinked. On the monitors, ship status displays and sector topographical maps cycled. Lines of text scrolled.

My seat held a roll of electrical tape. As I turned it over in my fingers, an electric jolt made me clench my teeth, squeeze my eyes shut. My neurons hummed.

The door to the airlock chamber clicked shut with a heavy mechanical thud. The thick metal muffled the hissing. Leaning back against my seat’s headrest, still clutching the tape, I froze. The air grew heavy. The cockpit lights seemed to dim, the edges of my perception closing in. A dozen shadows waited in the airlock chamber, their concentrated beams of hatred probing the metal door, seeking to burn me.

The door slid open.

I tensed, lips parting. What could I possibly say?

Mara emerged sideways through the gap, head bowed. As she stepped through, she shouldered the door shut behind her. The glowing diodes and bright screens of the control panel glinted on her helmet’s visor. She whipped around to face me. Her right arm shot out, leveling an electroshock lance. The two silver prongs at its tip lunged like viper fangs.

-----

Author’s note: I originally wrote this novella in Spanish about ten years ago. It’s contained in the collection titled Los dominios del emperador búho.

Published on April 10, 2025 22:49

•

Tags:

art, book, books, creative-writing, fiction, novella, novellas, scene, short-fiction, short-stories, short-story, writing

April 8, 2025

Neural Pulse, Pt. 9 (Fiction)

[check out this part on my personal page, where it looks better]

I edged a handspan of my helmet over the side of the embankment, to keep watch on the entrance of the shell of hexagonal panels. With the planet’s rotation, the star’s descending angle had lightened the blackness of the opening to a steel gray. I waited, lying prone, sunk a few centimeters into the sandy earth. From the gloom within the dome, I sensed the hollow vastness, the floor furrowed with the scars of ruts where maintenance robots had engraved circular tracks.

My helmet’s indicator notified me it had located Mara’s signal. I took a deep breath and waited for the woman to emerge. As if an army were cresting a hill, I sensed the shadows approaching. My heart hammered, and blood roared in my ears. I would stay out of sight.

From the gloom at the dome’s opening, a spacesuit frayed into view, venturing onto the esplanade, the containers following. I scooted sideways so the embankment hid me, and avoided breathing heavily lest the radio transmit it.

I peeked out. The woman and the containers had disappeared. And Jing? I had lost his signal.

Mara’s measured voice burst into my helmet.

“How goes it, Kirochka?”

I flinched, stirring the sandy earth, feeling the urge to leap up and sprint. Shadows were approaching from the opposite side of the embankment. They would surround me, press in on me, crush me against the earth until I suffocated.

“Something like that,” my voice trembled. “I’m in the cabin.”

“See you in a moment.”

What was keeping Jing? How could I wait for him to show himself? I had to seize the chance to break the artifact before Mara could stop me.

I scrambled up, slipping, spraying spadefuls of earth. I crossed the esplanade and plunged into the dome’s gloom. After descending the ramp about ten meters, I remembered to switch on my flashlight. I sprinted in a descending spiral, bracing a gloved palm when needed against the central pillar or the uneven rock wall. I filled my burning lungs with fresh, recycled air. My leg muscles throbbed.

A honey-colored light bathed me the instant I tripped. The maintenance robot tumbled through the air and bounced off the wall. I cartwheeled down the spiral, slamming against the excavated rock as my flashlight beam flared white off every surface my helmet struck. I slid prone down the ramp, bracing myself against the central pillar with my hands to stop.

I coughed. Sat up. My body’s tremors made the flashlight beam quiver. I shook the dust and sandy earth from my gloves. They were scuffed. Bristling fibers poked through the padding.

A chill ran through me from head to toe. I checked the oxygen levels on my lens. No leaks. On my vital signs display, my pulse fluctuated in the triple digits.

When I got up, I descended the ramp carefully, but within seconds, I was running. We had stolen the other robot, so I wouldn’t trip over that one.

The lens indicator alerted that it had locked onto Jing’s signal, and I slowed my pace. I breathed through my nose, but sweating as if in a jungle, I had to flare my nostrils to their limit to draw in enough air. I felt my way down the spiraling ramp.

I reached the entrance to a basement and peered in, exposing only a handspan of my helmet. I had expected to find the first sublevel, with the exposed mineral vein and the materializer, but I must have rolled past it tumbling downhill. Two of the construction robots lay gutted, and the third was missing an arm.

I hastened, walking just short of a run, to the back of the basement, where my flashlight beam mingled with the artifact’s tangle of levitating energy. I leaned against the curved, ribbed metal of a strut and scanned the entrance ramp. Perhaps Jing was dismantling the materializer on the first sublevel. Mara would have discovered I had deceived her.

I hunched before the undulating membranes of purple and pink energy. I probed the invisible shell containing the energy, as if hoping to find some crack through which to pry it open like a pistachio nut. I threw a punch, but the shell held. My hand ached as if I had struck a wall. When I gritted my teeth and struck again, a jolt shuddered up from my hand to my back.

I backed away. Bit my lower lip, refraining from growling. Jing would hear.

I took a running start and kicked the shell. It held. I kicked and kicked it until I slipped and fell flat on my ass. The radio would transmit my panting.

I swept the floor with my flashlight beam, searching for something that could help. I peered through the doorway to the adjacent basement area. Deserted. I ran to the dismembered ruins of the robots with their viscera of cables and circuits. Jing had left behind his crowbar and a meter. I gripped the crowbar.

I positioned myself in the middle of the basement and aimed my flashlight at the artifact. I brandished the crowbar, sprinted, and delivered a heavy blow against the shell, but the impact jarred the crowbar from my hand; it struck my shoulder and clattered to the floor. I trembled, seething. I hunched over, drew myself in, clenched my fists, and a growl escaped my lips, exploding into a guttural scream. My eardrums ached.

“Kirochka,” Jing said over the radio, startled. “Do you need help?”

I picked the crowbar up off the floor. I struck the artifact again and again, gasping for breath between each blow. The shell resisted as if, instead of being made of some penetrable material, I faced a repelling energy field. It would prevent me from breaking through, just as on a microscopic scale, atoms would never truly touch.

I leaned a forearm against the artifact, suppressing a gasp. Behind me, several shadows burst into the basement like an invading army through breaches in a rampart. I scrambled around the strut to my right, putting the artifact between myself and the spacesuited silhouette blocking the exit. My flashlight beam dazzled Jing, while his forced me to squint. The shadows coalesced into a wall, blocking my escape.

Here you are, of course. Acting on your own, against the majority decision. When I met you, I sensed you were unbalanced. That thing has damaged you because you’re too stupid to realize you should keep your distance from an unknown object, and now you intend to deprive humanity of a discovery that could lead to unimaginable technologies. You’re a miserable egoist, whatever your name is. An idiot who can barely pilot, clinging to that frigid scientist because no one else would bother paying you any attention.

I lashed the artifact with the crowbar. The phalanges of my hand screamed as if the blows had opened some fissure, yet I struck and struck again.

Out of the corner of my eye, I glimpsed Jing circling the artifact. I was dizzy, short of breath. The shadows flowed together shoulder to shoulder, hemming me in between them and the infinite volume of rock at my back.

A jolt shook my neurons, bleached my vision white. I shook my head. I pressed the tip of the crowbar against the invisible shell and, trembling down to my toes, leaned my weight onto the artifact as if I could force open a crack through which that tangle of energy would spill.

“You’ll break it, despite what your colleague decided,” Jing said.

“No, I’m just hitting it with the crowbar to see if it sounds like a gong.”

“You were right. Taking the artifact to the station would be madness. It should stay here, studied only by a small group of scientists, in quarantine. Never mind who gets the credit. But if you break it… maybe you’ll prevent a disaster.”

I coughed, spraying the inside of my visor with saliva. The air inside my helmet had grown sauna-hot, and my body was slick with sweat. I gripped the crowbar with both hands, spread my legs to brace myself, and lashed the shell. Each blow resonated through the fibers of my arms, making them vibrate like taut strings.