Dorothea Shefer-Vanson's Blog, page 11

July 13, 2023

Cheating Memory

Gabriel Lanyi, our friend, neighbour and colleague, is the author of this intriguing book and has given it its ambiguous title in order to take the reader into the labyrinthine region wherein memory resides. And in this case it is particularly labyrinthine because most of the author’s childhood and youth was spent under the Communist regime that ruled his homeland of Romania. In the course of the book he unravels the skeins of events, emotions and relationships that have remained with him, sometimes leaving the reader wondering where memory ends and invention begins.

If I were to pen a heading for this review I would call it ‘Entertaining, Informative and Erudite.’ In the course of reading the book, I found myself at times laughing uncontrollably at the antics which the author and his friends got up to in contending with the strict school system and the rigours of the Communist regime, and at others shaking my head in wonderment at the ingenuity of the devices he and others produced in order to evade the harsh decrees which were enforced from time to time.

In many respects, wherever they might find themselves young people attending school will generally find some way to kick against the system, as this reader remembers doing in her own distant youth. However, if the penalty for disobedience involves being despatched to a gulag, or recrimination against one’s parents, this undoubtedly has a sobering effect. When all is said and done, however, Gabriel Lanyi seems to have been undeterred in his efforts to defeat the system, although the process whereby he and his parents were ultimately able to leave Romania, was long and arduous. Nonethless, it is with a light-hearted attitude and an encyclopaediac familiarity with language and literature that he takes us through the vagaries of his youth and childhood, conjuring up images of people and places he encountered, or who encountered him, and describing them with ironic detachment, humour and, occasionally, affection.

If the reader perseveres to the concluding chapters of the book he or she will gain unimagined insights into the intricate relations between Romania, Hungary and Transylvania, and their complicated foundation in history and geography. Much of this part is devoted to trashing Bram Stoker’s depiction of Dracula, and expatiating on the numerous movie adaptations of the story. The irony of the cult status now accorded to Dracula and his seminal significance in Romania’s contemporary tourism industry does not escape Gabriel Lanyi’s critical eye and scathing pen.

While reading the book I was often lost in admiration of the author’s command of English, which is not his first language, and his ability to cite obscure works of literature – both prose and poetry – on several languages as well as to translate passages which, he asserts, are essentially untranslatable. I can heartily recommend this book to anyone who enjoys a well-written account of a life lived at a different time and place, the articulate depiction of which is rare indeed.

July 5, 2023

An Evening in Hungary

At the risk of repeating myself (and starting to sound like a cracked record) I feel impelled to write about yet another fascinating musical event I was privileged to attend.

‘An Evening in Hungary’ was the title given to a programme of music primarily from that country performed at the Austrian Hospice in Jerusalem’s Old City. The building, which houses a charming concert venue as well as an authentic ‘Austrian Kaffeehaus’ serving what is universally acknowledged as “the best Apfelstrudel in the Middle East,” is situated in the Via Dolorosa. It doesn’t seem to strike anyone as an incongruous juxtaposition to find brightly-lit cafes and restaurants serving tourists and the local population along the route supposedly taken by Jesus as he made his way to the site of his crucifixion, schlepping the instrument of his torture and murder as he went. To reach the venue we had to walk through the maze of streets and bazaars that comprise the Old City, and were relieved to find that the store-owners we passed on the way, and whom we occasionally asked for directions, were friendly and helpful.

Our attendance at the concert was the result of a chance encounter at a concert the previous week with the pianist, musician and psychologist, Dr. Laszlo Stacho (I’m omitting the Hungarian diacriticals his name requires), who is a professor at the Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest and a visiting professor at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. We fell into conversation with Laszlo, an engaging young man, in the interval of the concert, and after the concert we invited him to our home.

To cut a long story short, together with our neighbours who are also friends and fellow-translators as well as hailing from the same neck of the woods as Laszlo, we all spent an enjoyable evening in his company, and were eager to hear him play at the Austrian Hospice.

The programme, which consisted of Hungarian songs by Liszt, Kodaly and Bartok, as well as some by less well-known composers such as Ferenc Erkel and Gyorgy Kurtag, was performed by our new friend Laszlo at the piano accompanying a wonderful Hungarian soprano, Zsofia Bodi. Together the two provided an evening of music that was both a delight to hear and served as an introduction to a tonal and poetic world which was quite new to us. An additional dimension to our enjoyment was provided by the printed programme, which contained the words (in English translation) of all the songs, giving us another insight into the conceptual world underlying Hungarian music. Some of the songs, especially the folk songs (as arranged by Kodaly and Ligeti, for example) contained wry and sometimes raunchy humour, conveyed with charm and musical verve by both pianist and singer.

The programme also included two piano solos, Schubert’s Ungarische Melodie and Liszt’s ‘Sersum corda’ from Années de pèlerinage, giving the soprano a well-earned rest, and enabling the audience to enjoy Laszlo’s virtuoso playing. And so, at a time when our world is fraught with shadow and pain, a chance encounter led to an evening of fascinating and inspiring music.

June 29, 2023

Musica Aeterna

A small notice tucked away in our local newspaper caught my attention, and the promise of a performance of choral music by Russian composers seemed intriguing. In addition, the venue was an unusual one – the Ratisbonne Monastery in Jerusalem’s Rehavia neighbourhood. So we ordered tickets and turned up on the appointed evening.

The programme began with a brief organ recital. To our surprise, the organ in the church is relatively large and produces an imposing sound. It is a rare treat in Israel to hear a good quality organ, and the concert halls here are sadly lacking in that instrument. The recital consisted of three pieces by Bach and Handel and were played with consummate musicality by Julia Shmulkin, the invisible organist, who finally stepped forward and took a bow from the balcony when the audience applauded enthusiastically.

After the organ recital the Musica Aeterna choir filed into the body of the church. Consisting of about thirty individuals who are all, like their conductor and founder, Iliya Plotkin, originally from Russia, many of them are trained musicians. Their powerful sound combined with the church’s acoustics to reverberate around the nave, as they sang music by Kodaly, Rimsky-Korsakov and Rachmaninoff, to name but a few. The evening concluded with several Russian folk songs, some of a humorous nature, which the choir sang with gusto. The choir gave stirring performances of all the songs, attaining a high level of proficiency and professionalism.

The Musica Aeterna choir has been in existence since 1996 and is supported by the Jerusalem Municipality under its ‘Rainbow of the Arts’ project and the Ministry of Culture. The choir has participated in musical events in Israel and abroad and performs every Saturday at 12.30 at the Beit Jamal Monastery near Beit Shemesh. The intention is to hold monthly performances in the Ratisbonne Monastery in Jerusalem, and I am certainly looking forward to attending these in the future.

June 22, 2023

Political Correctness or Madness?

I left my homeland of England about sixty years ago and came to live in Israel for a variety of reasons, one of them being the weather.

The England that I left behind was a fairly stable country with regard to the composition of its population, which was largely white. There were, of course, some coloured people, or should I call them black people? In these days of Political Correctness I never know what is the acceptable term. Anyway, there were people who came originally from Africa or India or somewhere in the Caribbean, and had made their home in England. As the daughter of refugees from Germany I had no claim to being a native of the British isles, but having been born and brought up there I felt an affinity with its culture and history. Fortunately for me, my skin was white (pink), so I was not subjected to discrimination on those grounds.

After making my home in Israel I continued to interest myself in British culture, and even made a living through the use of the English language (translation and writing). My knowledge of Hebrew gave me the ability to read and speak it, but I never felt confident enough to write in it. All through my years in Israel I would return to England, mainly London, for a week or two most years to visit friends and family, as well as to enjoy the theatre, the ambience of the big city and feast my eyes on its familiar sights and scenes. Together with my husband, we took our children and grandchildren to visit the place where I had grown up and to which I still owe some kind of allegiance.

During one visit, Yigal and I attended a performance of Oscar Wilde’s classic and much-loved play ‘The Importance of Being Earnest.’ The play is replete with Wilde’s inimical brand of quips and witticisms, and rests on the concept of the unique brand of ineptness displayed by some members of the English upper classes. As usual, we got to the theatre, took our places and prepared to enjoy the play.

Imagine our shock when the curtain rose to reveal the main character, the eponymous Earnest of the play, speaking faultless English, seated in a comfortable armchair, expounding on various aspects of life, played by an admirable actor of African origin. This completely undermined any iota of trust or belief we might have had in the veracity of his representation of a typical upper-class twit, and nothing in the rest of the play – not the magic of Wilde’s linguistic and plot quirks, not the brilliance of the rest of the cast, not the convincing period costumes – could dispel the sense of disbelief and disappointment we felt.

I try to tell myself I’m not racist. I honestly don’t think I am. But I don’t see how anyone can think that casting a black person as the principal character in a play representing the English upper classes is a good idea and can in any way be convincing.

Something similar happened last week, as I tried to watch a TV version of Charles Dickens’ classic, ‘David Copperfield.’ Blow me down if the film didn’t start by showing the principal character, young David himself, running along the sandy beach to meet the family which takes him in, as a young Indian boy. Indian? David Copperfield? Never! However literate, enchanting, endearing and cute the little Indian boy, later replaced by an adult Indian actor, might be, they do not represent the David Copperfield of Dickens’s imagination, or mine. I wonder what Dickens himself would have to say about it.

I accept that English society has changed and that this should be represented in the arts, but please stop expecting us to consent to these travesties of English literature.

June 14, 2023

The Good Samaritan Inn

So many times, on our way back to Jerusalem after spending a few days at the Dead Sea or in Eilat, we passed the sign directing travelers to the Good Samaritan Inn and Mosaic Museum. I often wanted to make the slight detour to visit the site but was prevented by pressure of time or commitments.

However, on our last return journey we found the time to enter the area belonging to Israel’s Nature and Parks Authority where the building is situated. Our detour was well worth the effort, as we were able to tour the site containing many beautiful ancient mosaics, some of them situated in the open air and others housed in the building originally erected by the British Mandate authorities as a police station on the route between Jerusalem and pilgrimage sites at the Jordan river. The red-coloured rock of the region has given it its name, Ma’aleh Edomim, and the now-destroyed Crusader fortress that once dominated the crest was known as Castrum Rouge.

The parable of the Good Samaritan in the New Testament serves to illustrate the message that even someone from a lower class, as the Samaritans were considered to be then, could be more compassionate and charitable than a member of a higher class, such as priests or Levites, whose members refrained from helping a traveler who had been attacked and left at the roadside. The actual site of the event isn’t known, but archaeological excavations have shown that the spot where the museum is located dates back to a road station from the Second Temple period used by pilgrims to Jerusalem from Galilee and Gilead, as well as an inn from the Byzantine period serving Christian pilgrims. Samaritans separated themselves from Jews in the late First Temple period, though their religion also stems from the Torah and in many respects is akin to Judaism.

The art of mosaic evolved in the Greek world in the fourth century B.C.E., reaching the Land of Israel during the Hellenistic period, continuing to develop there subsequently. Producing a mosaic involved skill and teamwork, with builders who produced several preliminary layers of foundations as well as stonecutters and artists. Cutting tesserae was difficult and tedious, and paving a medium-sized church required more than two million of them. Samaritan synagogues differed from Jewish ones in several respects, though their mosaic floors were similar, and both differed from those found in churches.

Excavations have led to the discovery of many elaborate and beautiful mosaics in many places in Israel. The mosaics in the Good Samaritan Inn and Museum, which have been assembled from sites in Judea, Samaria and Gaza, date back to the Hellenistic and Roman periods, as well as the Byzantine (Talmudic) and Crusader periods. The intricate designs served as floors of public buildings, such as bath-houses, synagogues and churches, as well as private residences of wealthy individuals. Some of the mosaics show intricate abstract patterns while others depict animals and birds. One, taken from the synagogue at Gaza, even shows King David playing the lyre and wearing the robe of a Byzantine emperor, with a lion-cub, giraffe and snake listening to him. Some of the mosaics bear inscriptions or fragments of inscriptions, praising God or seeking blessings for donors or benefactors. Whatever their purpose, they serve as reminders of that most noble of human endeavours – the perpetual yearning for beauty and artistic expression.

June 7, 2023

Ghosts from the Past

Attending a concert recently in Jerusalem, I suddenly found myself surrounded by ghosts.

In the row in front of me sat an elderly woman whose face I recognized but whose name I had forgotten. When I had last seen her, about twenty years ago, she and I were both visiting an ailing friend, Miriam Ron, who subsequently died. I had met Miriam several years earlier, when we found out that as well as living near one another in the Abu Tor area of Jerusalem we both worked as translators, she from German to Hebrew and I from Hebrew to English. At the time I was involved in organizing the Israel Translators Association, and Miriam offered to help. In those ‘pre-historic’ days, before computers took over our lives and many of the tasks which had to be done by hand, Miriam and I spent many hours typing and collating stencilled pages which were sent out by snail mail to the members. In addition, all the envelopes had to be addressed by hand, and Miriam was a great help in all these tasks.

Miriam became a good friend and we came to enjoy one another’s company, often drinking coffee together and talking about the books we were translating. A quiet, self-effacing soul, she lived very modestly in a small house which had once been a gatekeeper’s cottage, surrounded by her extensive library of books about philosophy and mathematics – the subjects she had studied at university.

The elderly woman sitting in the row in front of me at the concert was in some way connected with Miriam’s sister, who had sent her to look after Miriam’s needs as she began to decline due to her illness. At the time Miriam told me that she resented her presence, feeling that she represented the desire to control her actions, although I’m sure that the intentions of all those involved were good. Be that as it may, seeing her at the concert brought back the memory of my lost friend with renewed intensity, beinging me both joy and sadness.

Sitting in another row nearby was someone who, like me, had once worked at the Bank of Israel. He had been a senior economist and in my role as translator and editor of publications we were in fairly close contact from time to time. His presence brought to mind my colleague in the Publications Unit there, Susanne Freund, the senior editor who had given me the job. Susanne was an eccentric genius, someone with firm opinions about anything and everything, and whose command of economics and mathematics was on a par with that of many of the senior staff in the Bank. She had been restricted in her career because she had not had the patience or motivation to finish her university degree. As an editor and translator she was much admired by the economists in the Bank of Israel and elsewhere, but she, too, unfortunately died after we had been working together for only two years, leaving me to take on a role for which I felt woefully unfit.

Though my degree in Sociology and Economics from the London School of Economics appeared to qualify me for the work in the Bank of Israel, I had not excelled in the economics segement of my degree, never expecting to work in that field. I remember getting very discouraged in my first few months at the Bank and after sharing my thoughts with Susanne she would sit me down and give me a ‘pep talk,’ encouraging me to persevere in grappling with the murky texts I had to translate. Together we began to compile a bilingual list of terms in economics, which we called ‘Jargon,’ and was a great help in my work.

Susanne’s death came as a terrible shock, as I had been abroad on holiday when she died, and had taken her to the doctor on my last day at work. When I returned to the Bank I had to get to grips with the work as well as trying to find someone to join me as translato and editor. After conducting a lengthy process similar to the one I had gone through, involving interviews, a transation test and personality assessment by an outside body, with the help and support of the head of the Publications Unit, the late Zvi Ron, a suitable candidate was found, and he turned out to be a great success. Fortunately, my erstwhile colleague and friend, Alan Hercberg, and my Hebrew counterpart at the Bank, Ruti Zakovitz, are both still with us, though by now, like me, retired.

And so, sitting in the concert, remembering Miriam Ron and my former colleagues in the Publications Unit, Zvi Ron, Zohar Rawe and of course Susanne Freund, I found myself surrounded by ghosts from the past and unable to ignore the ephemeral nature of life.

June 1, 2023

Music in my Life

I have often written here and elsewhere about music, musical events and my relationship with music. A recent trip to Italy, where I was unable to listen to music throughout the day as is my wont when I’m in Israel, brought home to me just how much significance music has for me in my daily life.

I am lucky enough to have had parents who saw to my musical education from an early age, introducing me to the music of Mozart (Eine Kleine Nachtmusik) and Mahler (symphony no.1) as well as a variety of other music via gramophone records. I was given piano lessons, at which I did not excel. I was taken to concerts (Handel’s ‘Messiah’) and even the occasional outing to Lyons’ Corner House, where the resident ensemble would play ‘Teddy Bears’ Picnic’ at my request (I was about five years old at the time).

Both my parents received a musical education and were taught to play the piano, as was customary in middle-class homes in pre-war Germany. I know that my father’s family were especially musical, and that my grandfather (whom I never knew) played the piano sufficiently well to organize chamber-music evenings in their home. The family attended concerts regularly and was one of the first to own a gramophone.

When I was growing up in England the large radio set dominated a shelf in our kitchen-living-room, and the programmes broadcast throughout the day by the BBC were a constant accompaniment to my life. The daily ‘Children’s Hour’ programme served to provide information and entertainment considered suitable for young people, and I still recall being moved to tears as a child when a programme about George Frederick Handel described the process by which he composed his oratorio, ‘Messiah.’ In my teenage years I remained an adherent of classical music, but was also happy to hear music by the Beatles and other pop groups (though not all of them).

Today in Israel we have a plethora of radio programmes broadcasting every kind of music throughout the day and night, though when I first moved to the country, some sixty years ago, broadcasting hours were limited. Popular Israeli songs that were heard over the radio also served as a uniting element for the disparate population in times of peace and war, and especially the latter.

My love of music even brought me the love of my life. After first meeting at a student party we quickly found out that we both loved classical music, especially chamber music, and our first ‘dates’ consisted of listening to one another’s records of our favourite compositions.

Back then the time devoted each day to broadcasting classical music was limited, whereas now it continues throughout the day and night, though some of the categories defined as ‘music’ often leave me confused (or even annoyed). I know that the intentions are good, and that the people who arrange such matters are capable and knowledgeable, regarding it as their mission to ‘educate’ listeners like me and broaden our musical horizons. And of course there are media other than the radio where my ‘fix’ of constant classical music can be obtained, but that requires slightly more effort than simply turning a knob, and it seems I’m even lazier in my old age than I was earlier on in life.

And so, while on holiday in Italy, I was hardly ever able to find classical music on a radio, not even in our rented car, though that was probably because of our ignorance of the system and the fact that we were not always within range of the broadcasting station. Almost by chance we managed to attend an opera in Parma, which was a real treat. When one of my grandchildren asked me, on our return, what I had missed most while away my spontaneous (and tactless) reply was ‘the music programme.’ At that moment I realized that a large part of my life consists of being able to hear music at all times – whether sitting at my computer, cooking or doing household chores, or just reading the paper or a book.

I wonder what my grandparents would have thought about my need to hear music at all times.

May 26, 2023

Ceremonies and Celebrations

There was a time when an invitation to a wedding or even a party would arrive in the post, artistically embellished, in an envelope with a stamp, plus a smaller card on which to confirm one’s participation in the event, and information about the time, date and place.

Call me old-fashioned, but I find it difficult to get used to being invited to a life-changing event such as a relative’s wedding through a message on my phone. And that’s only the beginning. In order to confirm participation one has to be technically astute, click on the appropriate response and make sure one doesn’t inadvertently delete the actual invitation. Said invitation included a link to the Waze app that would take us to the venue of the wedding, but not its actual address. That required some detective work on our part, but in this day and age of Googling anything and everything that’s no big deal.

In Israel today weddings have assumed some characteristics that might seem odd to previous generations. Secular young Israelis tend to look askance at the time-honoured formula employed for Jewish weddings. They also resent the imposition of religious rule by the rabbinate, which holds sway over all aspects of births, deaths and marriages in Israel. After all, what is the marriage contract as set out in the Ketuba but a business transaction between the father of the bride and the bridegroom, with the bride having little if anything to say in the deal? Even in non-Jewish weddings, without a Ketuba, the father of the bride ‘gives her away’ to the bridegroom. It’s more symbolic and less pecuniary, but the principle is the same. It all harks back to ancient, out-dated concepts of the rights of men and women.

At the event I attended the officiating ‘rabbi’ (who wore a kippa, was dressed in modern clothes and did not have a beard) conducted matters in a pragmatic manner, inserting comments and asides at given points, encouraging cheers and applause from the guests, using egalitarian everyday language rather than the formulaic ancient tongue of the religious ceremony. In accordance with tradition, the ritual seven blessings were pronounced by various men, who in this case were almost all relatives of the bridegroom, though I have attended even more radical weddings where some blessings were pronounced by female friends of the couple.

Of course, no wedding celebration can proceed without food, music and dancing, and that was certainly the case here. The grub was tempting and plentiful and the music was loud and energetic, enabling the young people to gyrate and the older ones to sit and eat (and everyone to drink). During the reception prior to the ceremony a unique touch was provided by a young woman wearing an elegant dress who mingled with the guests as she played the saxophone, accompanying the DJ’s music on the loudspeakers.

A final, delightful touch. As we were leaving we passed a table laden with small pots containing various herbs, and we were encouraged by the person in charge to take one. And so, as we drove home, the sweet smell of our basil plant scented the air in the car, leaving us with a lovely memory of a memorable event.

May 17, 2023

Italy’s Five Towns

Of course, Italy has far more than five towns, but the specific five towns in northern Italy known as the Cinque Terre form a geographical and cultural unit along the mountainous coastal area which is a continuation of the French Riviera and shares many features with it. The tree-covered mountains sweep down to the sea, where villages and small towns once engaged in fishing and sea-faring, but today are focused mainly on tourism.

The train line which connects the coastal towns goes through endless tunnels, with occasional brief exits into bursts of daylight and the sight of the sea. We visited two of the towns by boarding the train at Riomaggiore, where we had to park our rental car at the top of the hill and walk down to the station. Together with the throng of tourists, we boarded the train there and alighted at Monterosso, where there is a fine promenade with cafes, restaurants and opportunities to taste some good ice-cream. On our return trip to Riomaggiore we found ourselves facing the long uphill walk to our car. That was not easy and taught us not to repeat the experience.

The region is served by a network of narrow, winding roads, meaning that driving around to view the various sights or find a place to eat involves moments of stomach-turning anxiety for someone like me, who is scared of heights and fearful at every turn and twist in the road. Our situation was not helped by the insistence of our Waze application to speak to us in Italian. My knowledge of the language is very limited, though I could work out phrases meaning ‘at the roundabout (rotunda) take the first exit (prima uscitta),’ but the result was not always satisfactory (i.e., we didn’t always get to where we wanted to go). A phone call to our computer wizz son in Israel resolved the problem, and after that we were able to be guided in English. Our AirB&B near the village of Volastra was a spacious farm-house, with two large rooms, a large kitchen and a terrace with a view of the sea. On the day the rain kept us in the house we were able to watch Italian TV with its French-language Arte channel, and saw two films dubbed into French (The Pink Panther and Die Brucke), as well as various travel documentaries (also in French).

Our trip also involved short stays in larger towns in the region, starting in Milan with its magnificent cathedral and Brera Museum with the masterful painting by Caravaggio of The Supper at Emmaus. We also visited Genoa, once a major port and still a significant sea-going presence in Italy, and we ended our trip with a brief stay in Parma, home of the famous Parmesan cheese. It so happened that there was a performance of Leoncavallo’s short opera Pagliacci that evening, and there were still some tickets to be had. So for our farewell to Italy we were treated to a wonderful performance of the tragic opera, with a colourful stage filled with constant action by actors, singers, dancers, acrobats and clowns, reproducing the production as originally staged by Franco Zeffirelli. What a magnificent show that was!

We were impressed by the cleanliness of the towns we visited, even in Genoa, where everyone seems to have a dog on a leash. What a pity that here in Israel we cannot emulate a similar standard of public responsibility.

May 1, 2023

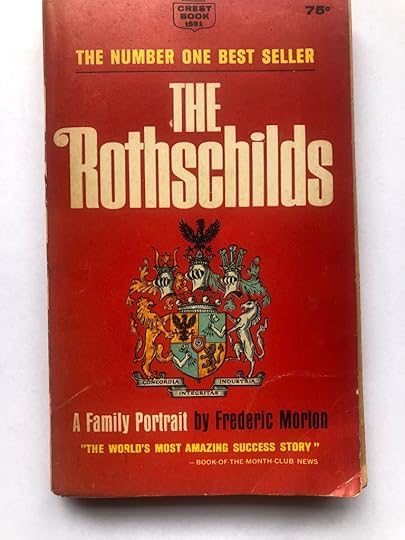

The Rothschilds, a Family Portrait

While sorting through and getting rid of books in order to accommodate a new item of furniture I came across this volume by Frederic Morton, which I had given to my father for his birthday in 1965. It still bears my dedication, ‘To Daddy, with love,’ reminding me of his association with the English branch of the Rothschild family through its patronage of the Jewish charity of which he was the Secretary.

So I took up the faded pages and began to wade through the history of the complex relationships and even more complex business and financial concerns of that august family. The author has done an admirable job of presenting its history, starting with its humble origins in the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt, blossoming by dint of intellectual brilliance and strong family ties into a mammoth financial and business enterprise on the international stage. The starting point was in 1764 when the founder of the family fortune, Mayer, returned home from a yeshiva near Nurnberg where he had been sent to study to become a rabbi. When both his parents died and the payment for his studies ceased, some relatives secured an apprenticeship for him in the Jewish banking house of Oppenheimer in Hannover, one of the network of principalities that later merged to become Germany.

In Frankfurt Jews were restricted to living in the ghetto, an area consisting of a single dark alley near the city wall. The ground floor of some of the houses served as shops, mostly selling second-hand goods, and Mayer Rothschild joined his two older brothers in this trade. He developed an interest in old coins and medals, managing to engage the interest of the local ruler, Prince William of Hesse-Hanau, as well as setting himself up as a currency exchange agency. This eventually enabled him to serve as private banker and money lender to the local aristocracy.

Mayer married Gutele Schappner, and the couple went on to produce ten children, five sons and five daughters, though another ten babies did not survive. As the children, particularly the boys, grew Mayer benefited from their services delivering messages and packages to his various clients, many of whom were in high positions. The boys displayed a combination of mental acuity and the ability to engage in transactions that gave Mayer considerable advantage in his business dealings. The eldest, Amschel, went on to eventually become the treasurer of the German Confederation, Salomon, the second, achieved the same exalted station in imperial Vienna, Nathan, the third, rose to have more power than any other man in England; fourth was Kalmann, who ‘wound the Italian peninsular around his hand,’ and finally Jacob, who was to lord it in France during Republic and Empire.

When Napoleon assumed power in France and elsewhere he appointed the financial agency of Rothschild and Sons as the legal successor to Prince William’s exchequer, enabling the Family to collect debts owed to the Prince throughout Europe. During this period gold served as the principal means of payment, and the Rothschild agency managed to collar a considerable amount of it. In September 1806 the status of the Rothschild agency was changed, with its shares being held by Mayer together with his sons, who were by now spread out throughout Europe. In England Nathan spotted the opportunity provided by the need to finance military operations against Napoleon in Europe, using his financial astuteness and family connections to raise funds and spread the risk. Among his august clients was the East India Company, whose entire stock of gold bullion he purchased, enabling him to provide Wellington with the wherewithal for the battles ahead while at the same time creating tremendous wealth for the Family.

Mayer and his sons were able, by dint of their diligence and brilliance, to build a financial empire extending throughout Europe and the world. The Rothschild sons and grandsons tended to marry their Rothschild cousins and nieces, ensuring the retention of the Family fortune and genetic propensities, while the female members of the clan often married into the European aristocracy. The Family initiated and financed the construction of roads and railways all over the world, were instrumental in the acquisition of the Suez Canal by Britain and have been instrumental in the creation, settlement and establishment of Israel, in addition to their extensive charitable work, which often remains anonymous. While the palaces built as residences by the Rothschilds in London, Paris, Vienna and elsewhere, have in many cases been sold or converted into hotels and embassies, and some of their country estates flourish under a different aegis, the Rothschild Bank is still a significant institution in the financial world, having endured world wars and economic crises. In recent generations Rothschilds have been leading botanists and zoologists, collectors of fine art, and patrons of the arts and sciences. The aura of wealth and indulgence associated with the name of Rothschild endures till this day among Jews and Gentiles all over the world.