Dorothea Shefer-Vanson's Blog, page 10

September 27, 2023

In Search of Lost Time

Several years ago I bought all six volumes of Proust’s monumental work, treating myself to both the French original and the English translation by Mayor and Kilmartin, and thus embarked upon the journey into the remote but vibrant world of French society, manners and mores of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. In the course of my reading, which has taken several years and veered from the French to the English and back again (but mostly in English), I have become acquainted with a wide panoply of characters as well as with the complex observations contained in Proust’s disquisitions on a myriad subjects, encompassing art, philosophy, architecture, social mores, psychology, sociology, literature and, above all, the nature of Time itself.

The first lines of the first volume set us firmly in the hero’s childhood, with the immutable sentence “For a long time I would go to bed early.” (Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.) And so, as we read on, we find ourselves absorbed into the life and times of the hero as well as those of the people he encounters in his daily routine. Later on, as he grows older, as he gets to know more people, he becomes involved in the social life of French aristocratic society, develops friendships, has love affairs and moves from one physical setting to another. These settings are brought to life through the individuals who people them, whether they be the servants who constitute the background to the daily routine and who nonetheless play a role through their personalities and their machinations, described so vividly by Proust. Foremost among them is Francoise, the cook and general factotum in his parents’ house, who plays a prominent part in young Marcel’s life, has definite likes and dislikes and doesn’t hesitate to express an opinion about events and individuals. She also features in his final volume, where he equates his writing a book with her sewing a dress, but also refers to her presence and attendance to his needs while he is working, thereby bringing his association with her to a full circle, and so we realise that it is she, the ignorant, illiterate but good-hearted peasant woman who is the backbone and eternal verity of his life. Throughout the books contemporary events and movements impinge on the lives of the characters, whether this be the Dreyfus affair and the effect this had on French society and culture, the First World War, with the bombing of Paris and evacuation of its residents, the life of the leading actresses of the day, or the life of military conscripts.

Proust depicts the social life of the higher bourgeoisie first in the countryside (‘Combray’) and subsequently in Paris. Through his parents he gets to know the families who live in the region and starts to take his place in society. Through their vacations by the Normandy seaside (‘Balbec’) he becomes acquainted with (and fascinated by) various young women, and these are depicted as complex, volatile yet attractive beings. His on-off love affairs with first Albertine and then Gilberte run through the six volumes like a silvery stream, and it has been said that it was Proust’s own homosexuality that led him to choose feminised forms of male names for these characters. The theme of homosexuality is hinted at or described extensively throughout all six volumes, and especially in volume 4 (‘Sodom and Gomorrah’). It is by now impossible to disconnect aspects of Proust’s personal life from his fictionalised account of his life as presented in ‘In Search of Lost Time,’ and this is particularly the case towards the end of the sixth volume, when he ‘suddenly’ realises that it is his mission in life to write a book and ‘predicts’ that in order to do this he will have to sleep by day and write at night, which is what he actually did (and had been doing for several years). Volume 6 contains many profound insights into the nature of Time and its effects on life and the individual, as well as into the nature and role of literature, constituting an object lesson to every aspiring writer.

Now that I’ve managed to make my way through all six volumes I feel that it is incumbent on me to begin from the beginning and start reading them all once more, this time with a greater understanding of what is happening and where the author is taking me.

September 21, 2023

A Book Launch

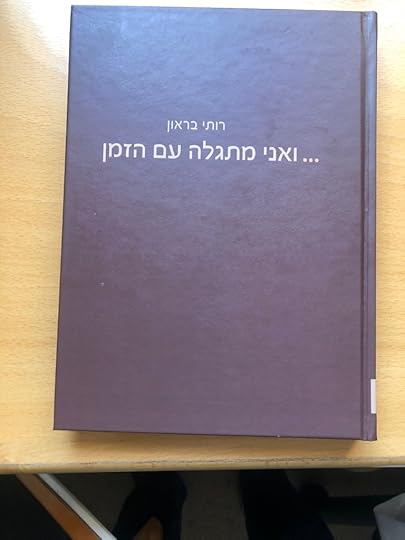

Ever since Yigal (my other half) retired from his high-powered high-tech career he has been involved in numerous non-high-tech activities. These range from pursuing his interest in art to become an expert in the paintings of Caravaggio, extending his study of the Ancient Near East to become a volunteer guide at the Bible Lands Museum, and imparting of his insights and understanding to teach courses in creative writing in our local pensioners association. In this last framework he has established a name for himself and a following, with new recruits to his courses swelling the ranks of each session.

This is an odd state of affairs. After all, I’m the one who writes books, but Yigal teaches writing (though not to me). There is, of course, something of a language barrier, as I write in English and his courses are given in Hebrew, but there is no doubt that he has developed a technique for drawing out the hidden writing talent of people who would otherwise never have set pen to paper. It is an admirable quality, involving psychological insights and literary skill, and is obviously much appreciated. So much so, in fact, that he was recently invited to attend the launch of a book published by one of his former pupils.

I accompanied him to the event, curious to see what form this book launch would take. I have published eight novels, and although the launch of my first book was hosted in her home by a kind friend, with a small gathering of friends and a sumptuous tea, I somehow ‘forgot’ to launch my subsequent books. They were published on Amazon, I tried to publicize their appearance through various internet intermediaries, and c’est tout.

The book launch in question was held one early evening in a nearby Moshav which provides venues for events of various kinds. As we entered the hall we were greeted by tables laden with light refreshments, with savoury items on one table and cakes and drinks on another. There was a bar seving wine and other alcoholic drinks, and chairs were set out facing a stage at the side of which a young lady was playing pleasant music on the piano. As more and more people arrived, some of whom we knew, the atmosphere grew warmer. The hostess-author of the book in question, a collection of poems she had written in the years since the death of her husband, moved among the guests, welcoming them and introducing them to one another.

After a while we were summoned to take our places and the ‘show’ began. About a year ago Ruti, the hostess-author, had left Yigal’s writing group and joined a different one, and it was the leader of that group who had instigated the publication of the book and also served as compère at the book launch. She introduced the author, who needed no introduction, and started the proceedings by inviting the pianist to play something. This was followed by a reading of a few of the poems in the book by an actor, as well as by Ruti and her teacher, an extempore speech given by Ruti’s son, Ran, who had flown in specially from abroad, where he lives and works, more musical interludes, some video clips of Ruti’s grandson, Ran’s three-year-old son, and more poems read out very expertly by the actor (also called Ran). After about an hour of this the event came to an end and everyone was invited to come to the central table, where Ruti sat in front of a pile of her books, and prepared to hand them out and write a personal note to each and every participant. When Yigal approached her she wrote a few words in flowing Hebrew, thanking him for enabling her to write, and when we looked at the list of acknowledgements printed on the flyleaf we found Yigal’s name there, too, as the person who had been the first to introduce her to writing.

The Hebrew title of the book can be translated as ‘And I Am Revealed With Time,’ possibly indicating that the healing process after the death of her husband has been long and arduous. Many of the 250 poems in Ruti’s book concern that loss and the sadness that has encompassed her since then. One can only hope that the process of writing and publishing the poems has been of therapeutic value and has done something towards helping to heal Ruti’s pain.

September 14, 2023

Cause for Optimism?

Whether it’s because I have an M.A. in Communications (with a thesis on the language of the news) or am simply a glutton for punishment, I find it impossible to cut myself off from the nightly news broadcasts on television. The anchormen and women do their best to present the facts in measured tones, keeping personal views out of the picture, but once they are surrounded by a panel of journalists and pundits with varying political views all hell generally breaks loose. No one has the patience to hear anyone else’s opinion, and the moderators invariably find themselves trying in vain to keep some semblance of order and civilized debate as everyone keeps interrupting everyone else.

It’s then that I switch from one channel to another in the hope of finding some modicum of decent behaviour, but am generally disappointed. In Israel there are several channels presenting the evening news at more or less the same time, and when the level of argumentation gets too unbearably high I sometimes seek respite in one of the remoter channels, such as the one about travel to distant lands, the one about advances in medicine, or the one with demonstrations of how to roast a joint of meat.

Recently, 12th September, in an unprecedented event, we were ‘treated’ to a full day of live TV coverage of the review by Israel’s Supreme Court. The subject was the appeal against the revocation of the amendment regarding the concept of Reasonableness as a criterion for striking down or accepting a law. According to Wikipedia, “In constitutional and administrative law, reasonableness is a lens through which courts examine the constitutionality or lawfulness of legislation.” Israel has no written constitution, and consequently it is the concept of lawfulness that has to be considered.

Because the issue is regarded as being of paramount importance for current and future legislation, TV cameras were allowed into the inner sanctum of the Supreme Court, where all fifteen Supreme Court justices sat in judgement – another unprecedented event.

The case for the government, namely, in favour of striking down the concept of Reasonableness, was a distinguished and capable lawyer, Ilan Bombach, while a number of lawyers presented the case for retaining it. What struck me as I watched the proceedings (admittedly not for the full thirteen hours) was the happy realisation that it is still possible in Israel to have a reasoned and civilized discussion about issues which are of salient importance. Mr. Bombach presented his case in measured tones, and the justices asked him questions or made comments in a way that was neither heated nor inciting.

In the course of his argument Mr. Bombach stated that the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, drawn up and issued on 14th May 1948 and signed by the thirty-seven member of the People’s Council (the predecessor of the Knesset) was not legally binding in a court of law or the Knesset. This view was criticized by the justices, and was later retracted by Mr. Bombach. That Declaration states inter alia, that the Jewish people, though exiled by force, kept faith with their land in all the countries of their dispersion..and in recent generations came home in their multitude. It goes on to state in paragraph thirteen: “The State of Israel will be open to Jewish immigration and the ingathering of the exiles. It will devote itself to developing the land for the good of all its inhabitants. It will rest upon the foundations of liberty, justice and peace as envisioned by the prophets of Israel. It will ensure complete equality of social and political rights for all its citizens, irrespective of creed, race or sex. It will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, education and culture. It will safeguard the holy places of all religions. It will be loyal to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.”

It so happens that I possess all six volumes of the English edition of ‘Major Knesset Debates,’ most of which I translated several years ago (edited by Netanel Lorch). I have studied the Hebrew and English versions of the Declaration of Independence therein and must admit that no mention is made of Israel being founded on democratic principles, although the content of paragraph thirteen and the reference to the Charter of the United Nations imply this.

Mr. Bombach and several justices referred to Israel as being a Jewish and democratic country, and this seems to be generally taken for granted. Now all that remains is to define democracy, and everything will fall into place. Unfortunately, opinions still seem to be divided in Israel as to what democracy means, and whether Israel is a country in which the rule of law prevails, and by whom it should be upheld. This constitutes the basis of the issue which is currently dividing the country, and it is up to the Supreme Court to clarify the issue.

September 6, 2023

A New Dawn?

For the last few months Israel’s long-suffering population has been subjected to a double barrage of government legislation on the one hand and demonstrations protesting said legislation on the other.

Anyone living in Israel who is not completely cut off from the news media is unable to avoid involvement at some level in the ongoing dispute between the warring parties, and I use the term ‘warring’ advisedly because that is essentially what is happening between the two main segments involved. As is the case in many countries, the result of the recent general election left Israel with no party having a clear-cut majority. In the past this situation has generally been overcome by forming a coalition government, and in recent years Binyamin Netanyahu has proved himself most adept at this. When a rival party used the same tactic to form a government a year ago he refused to acknowledge its legitimacy and expended considerable energy and resources on undermining it, which took him just a year and a half to achieve.

The government which he has subsequently formed combines his right-leaning Likud party with a motley crew of ultra-orthodox, rabid right-wing and self-serving adherents. It is this collection of individuals which now seeks to radically alter Israel’s legislative basis, overthrow its system of checks and balances and impose laws which refer to Talmudic principles as the basis on which society is to function.

When I immigrated to Israel in the 1960s, before the Six-Day War, it was essentially an open, liberal society where orthodox, ultra-orthodox and secular Jews lived more or less in harmony. Today the fear among secular Jews like myself is that the narrow view of orthodox Judaism has prevailed in the government and is being being imposed on society in general through the new legislation. After all, by revoking the criterion of ‘reasonableness’ in assessing laws, what is there to stop the government from restricting the rights of women and lgbt individuals in accordance with orthodox Jewish practice? And the concepts of equality and human rights, as enshrined in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, are irrelevant for those in the government who seek to repress the Palestinian population, whether in Israel proper or in the West Bank territories.

Today most Israelis are secular, but there’s no guarantee that this will continue to be the case. Reproduction rates among orthodox and ultra-orthodox Israelis are far higher than those for the secular population. As a former member of Bnei Akiva in England, I know that the ultimate aim of even the most moderate of orthodox Jews is for Israel to become a state based on religious law.

That is a prospect that is anathema to me and all my compatriots who go out to demonstrate and remonstrate whenever they can. And it is a tragedy to see Netanyahu and his government ride rough-shod over anyone who adheres to the open-minded spirit that once characterised Israel, causing internal dissension and wreaking havoc in so many spheres.

August 27, 2023

Queens of Jerusalem; The Women Who Dared to Rule

by

Katherine Pangonis

Pegasus Books Ltd.

As the author notes in her preface, ‘This is a book about women and power.’ The wives and daughters of crusader kings and princes in the Holy Land sometimes found themselves in the position of default ruler upon the death of the husband or father who had been killed in battle or fallen victim to one or another of the diseases that were rife in the region in the period when the Crusaders ruled. The author states explicitly that since the record has in the main been written by male historians the role of women has been neglected, and she regards it as her mission to rectify this omission.

The First Crusade began in 1096 when, inspired by religious fervour and incendiary rhetoric, many thousands of men throughout Europe ‘accepted the cross,’ took up arms and travelled by land and sea, together with their horses and siege weapons, to conquer the Holy Land, known to them as Outremer. The Crusade leaders were princes and dukes who owned lands and could recruit fighting men. In general women were not included in the fighting forces, but it seems likely that family members accompanied the fighting forces, as well as providing services such as cooking and washing, as well as satisfying the men’s sexual needs. After managing to wrest Jerusalem and other cities in the region such as Edessa and Antioch (in modern Lebanon and Syria) from the Arab Caliphate in 1099, the Crusaders established the Kingdom of Jerusalem, crowning Godfrey de Bouillon as the first monarch, proclaiming him Defender of the Holy Sepulchre. He died after just one year as king and was replaced by Baldwin of Bourcq who, together with his wife, Morphia of Melitene, had four daughters, Melisende, Alice, Hodierna and Yvette.

The role of women in European monarchies was to serve essentially as brood mares, providing sons to inherit their father’s mantle as ruler, as well as consolidating their husband’s wealth and power by bringing a rich dowry into the marriage. In the case of Baldwin and Morphia the absence of a son and heir meant that the succession would pass to Melisende and through her to her husband, Fulk of Anjou. In 1131 Baldwin died and was succeeded by Melisende and Fulk, acting as regents for their child Baldwin. In 1143 Fulk fell in battle, leaving Melisende as sole ruler and regent for her 13-year-old son. From then until her death in 1181 Melisende ruled the Kingdom of Jerusalem, either directly or indirectly, managing the affairs of the monarchy, repressing rebellions by other rulers such as that of her sister, Alice who had married Raymond of Antioch and succeeded him after his death. Cities such as Acre, Tiberias and Tripoli had their own regional monarchies, and the rivalry between them often ended in military clashes. It was customary for defeated rulers to be executed or imprisoned for long periods, often in terrible conditions, until they could be ransomed, and it was often their wives or daughters who raised the funds to redeem them. This was the case with Eleanor of Aquitaine, who travelled the length and breadth of Europe to raise the ransom for the son she had borne to her second husband, Henry Plantagenet of England (Henry II), and who was known as Richard Lionheart.

Melisende’s son was eventually crowned king Baldwin III, and his son and grandson eventually became Baldwin IV and Baldwin V of Jerusalem. Her second son, Amalric, married Agnes of Courtenay, and their son, Baldwin IV, died young, leaving the throne to his sister, Sybilla of Jerusalem, who first married William ‘Longsword’ of Montferrat and then Guy de Lusignan. At her marriage ceremony Sybilla ceded her power to her husband, and although they succeeded in defeating the rebellion raised against them by Raymond of Tiberias, this eventually brought about the Crusader kingdom’s downfall, as Raymond allied with the forces of Saladin, allowing them to march through his territory in what eventually led to the crucial Crusader defeat at the battle of Hattin on 4 July 1187.

Saladin succeeded in routing what remained of the Christian forces, retaking Jerusalem and all the other Crusader strongholds. The fortresses and castles the Crusaders had built throughout the Holy Land were all destroyed, though the ruins of many of them still remain as mute reminders of the forces that once ruled the land. Place names such as Beaufort and Castel preserve their memory, as do the contemporary chronicles written in Latin by William of Tyre and in Arabic by Ibn Al-Athir, on which the author based her research.

August 16, 2023

A Village Festival

Every year, on the 15th of August, which is a national holiday, the sleepy village of Domeyrot is transformed. It is suddenly filled with visitors, vehicles and local inhabitants who have emerged from their houses, gardens and farms. Once a year the empty field next to the building housing the mayor’s office, the local post office and the hall for public events (salle polyvalent) is filled with stalls set up by villagers and anyone who has paid in advance and upon which are set out all the items that people are eager to sell. In many cases these are discarded clothes and books, items of crockery, knick-knacks, toys, vinyl discs, and even jewellery, all on the principle that ‘one person’s junk is another person’s treasure.’ Similar weekend fairs (‘brocantes’) are held all over rural France in the summer, providing entertainment and occupation for the local population and entertainment for the tourists.

The treasure-hunters are out in force. They are the ones who come from far and wide early in the morning in the hope of finding some unwanted article that turns out to be a genuine antique or item of value. Later on come the families, equipped with shopping bags, looking for some specific household item or bargain that will replenish a diminished stock. Bargaining is customary, and everything is conducted in a friendly spirit, with sellers eager to unload unwanted ‘stuff’ and buyers hoping to find what they desire or chance upon something unexpected that suddenly seems attractive. In our case in the past we have managed to acquire fine sets of crystal wine-glasses, champagne ‘flutes,’ and whisky glasses with matching decanter.

But the fun doesn’t end there. A team of volunteers from the village sets up large tents with tables and benches alongside the areas in which fast food is cooked in outdoor kitchens and drinks are provided – all for a modest fee, of course. As midday approaches the area is filled with customers eager to assuage the hunger aroused by the hunt (for bargains), and an orderly queue forms as people wait to pay one of the volunteers manning the stalls and receive the food they have ordered. To be honest, the standard of the cuisine is less than admirable, but most people seem to be happy to munch their over-cooked sausages and soggy chips, washed down by a plastic cup of beer or a real glass of wine they have ordered at the adjacent tent.

During the day a marathon race and less-energetic public ramble are organized, with officials regulating the traffic and a public address system announcing winners and losers. A Petanque (bowls) competition is held, with the participation of many local players, and a trophy is awarded.

In the evening the village hall hosts a dinner, for which people have to register in advance. It is an opportunity for the local residents to get together in a spirit of companionship, as a break from the relative isolation of their daily lives in this rural community. On the evening when we participated in the meal some sixty people were seated at trestle tables and the food was served by young volunteers from the local population. The menu consisted of a wedge of potato pie accompanied by slices of salami, wine or beer according to one’s preference, followed by the obligatory cheese slice, a small helping of icecream, and coffee (or herb tea in our case). Our table neighbours were a pleasant couple from a nearby farm who grow a wide variety of vegetables, which they sell at local markets. It was a welcome opportunity to speak French and learn a little about the local way of life.

Soon our all-too-brief stay in Domeyrot will come to an end and we will return to the relative hustle and bustle of our life as retired persons in not-so-rural Mevasseret Zion, hoping that the interval of total calm will continue to soothe our spirits for many moons to come.

August 10, 2023

A Cultural Desert?

In Paris it is customary to look down on the rest of France as being less sophisticated, less cultured and less fashionable. This applies tenfold to the region in central France known as the Creuse, which is primarily rural and where cultural events are considered to be few and far between, if they even exist at all.

However, during our summer visits to this region in recent years, now officially renamed ‘New Acquitaine,’ we have found this to be far from the truth. When we first came here some fifteen years ago we were able to attend weekly concerts in the various gorgeous mediaeval churches of the region featuring soloists, instrumental ensembles and choirs from all over Europe. That particular series of concerts, known as ‘The Voice of Summer,’ has been discontinued but has been replaced by other musical events. One of these is given by a group of soloists from the Paris Symphony Orchestra, who spend a week or two every summer giving concerts throughout the Creuse. Of the two we will be attending next week one is to be given in a nearby church and the other in the elegant orangerie of the local chateau. We have attended these concerts in the past and they are always sold out and provide a welcome interlude of classical music, often accompanied by erudite explanations given by the cellist, who is the driving force behind the organization of the concerts.

By chance, just after our arrival here last week, we heard about a concert consisting mainly of chamber music to be given by a group of young musicians. As I wrote in a previous post, it was a joy to be able to hear a chamber performance of Mozart’s piano concerto no.9. This, too, was given in a local church and was sold out. In fact, as we took our places we were able to witness the organisers bringing in extra chairs to accommodate all the music-lovers who wanted to attend the event.

Another series of concerts given locally is called ‘The Noise of Music,’ and consists predominantly of contemporary and experimental music, again given in local churches. This kind of music, defined as a ‘sonar experiment,’ is not really my cup of tea but I must admit that it seems to be immensely popular, with persormances sold out and people coming from all over France to attend them.

Finding the announcement of an organ recital to be given in a nearby church on a Sunday afternoon, we went along and found a young man by the name of Quintus Blundell, who is originally from New Zealand, setting up his equipment, which consisted of a sophisticated synthesizer and two large loudspeakers. In fluent French he proceeded to introduce the various pieces he had chosen to play – a selection of music by Bach, Byrd and others, including an arrangement of the largo from Dvorak’s 9th symphony, which he introduced as being forever associated with an advertisement for bread on British TV. He began by playing a stirring arrangement of Parry’s ‘Jerusalem,’ and so, by some fluke of fate, he managed to combine the three main strands of my life – England, Jerusalem and France – in one moment, and sitting there as the music soared and echoed around the church I couldn’t help thinking, with tears in my eyes, of Blake’s moving words:

‘I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant land.’

As well as various musical performances, other events on offer which we may or may not attend, depending on our timetable and interest, include a reconstruction of a mediaeval pageant, guided walks involving explanations about the birds of the region, whether at night or by day, visits to chateaus, star-gazing events, markets, guided tours of Templar churches, antique shows, horse shows and son and lumiere performances focused on ancient buildings.

It was in this region that the crusades began, inspiring thousands of believers to set out for the Holy Land in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, conquering it and establishing the Kingdom of Jerusalem’ there, until defeated and driven out of that territory two hundred years later by Saladin and his Moslem armies. Buildings, churches and place names still bear traces of that time, which is irrevocably etched into the history of the region.

Throughout the summer months musical and other cultural events are held all over France. And so, as you can see, the Creuse is full of musical and other activities and by no stretch of the imagination can it be called a cultural desert.

August 3, 2023

Occupational Hazards

In conversation recently with a musician friend it suddenly dawned on me that because he is so knowledgeable about music, musicality and musicianship it is virtually impossible for him to enjoy a concert or recital in the same way that I, as an ignorant layperson, can. Anyone with extensive knowledge of a particular subject is at risk of being unable to enjoy a work of art or manufactured item if it falls within the sphere of his or her expertise. The application of rigorous professional standards as the yardstick by which enjoyment is reaped is bound to end in disappointment.

And so, a house-painter who is paying a social visit cannot help casting an appraising eye around his host’s house and drawing conclusions about the professionalism, or lack thereof, of the work. Presumably carpenters, bridge engineers, architects, gardeners and many others would find themselves in a similar situation. That’s tough.

I have noticed that this applies to myself, too, whenever I read a book or text in English. Having spent many years as a translator/editor, it is impossible for me to read a book without mentally correcting, editing or proofreading it. This generally tends to mean that I make a mental note of the fiasco but that is more or less where it ends, and I continue reading though with a more critical eye. This in fact happened recently, when someone gave me a copy of his recently published book. As I read the text, which was generally well-written, I noticed one or two slight grammatical errors or typographical flaws which marred the flow of the narrative for me.

I took up a pencil and began marking in the margin the points which I felt needed to be corrected, and when I had finished I summoned up my courage and showed the book to the author. Contrary to my expectations, he welcomed my remarks and at a later meeting informed me that he had incorporated most of them, in the next edition of his book.

One of the occupational hazards of having spent most of my working life dealing with both Hebrew and English means that I have a special sensitivity to language, whether written or spoken. Thus, in recent times I have come to abhor certain ‘slang’ expressions in both languages, such as ‘I was sat’ in English and ‘zotti’ (instead of ‘zot’) in Hebrew. Once upon a time this kind of terminology was reserved for cheeky teenagers or persons with minimal education, but nowadays it is widely used by all and sundry, including journalists, academics and members of the professions. I still feel physical unease when I hear them, but they are used so abundantly that I am afraid I will soon find myself accepting them as part of normal speech. And don’t get me started on people who say ‘Best regards from John and I.’ Would they say ‘regards from I’? Is it just ignorance, or has the English language abandoned every vestige of correct grammar? Another annoying habit of Hebrew speakers is to omit the ‘h’ sound in words. Here, too, it seems to be endemic throughout all social levels, and in my view it puts Hebrew speakers on a par with native Londoners, also known as Cockneys, whose level of education generally tends to be minimal.

Another strange usage is the substitution of ‘mum’ for mother. I have heard Prince Harry refer to his late mother, the much-mourned Princess Diana, as ‘my mum,’ which I take to express a son’s affection for his departed parent. Or perhaps it reflects his attempt to show that he is ‘just like everyone else,’ and ‘a man of the people.’ Be that as it may, imagine my recent shock when I read in the Acknowledgements section of a serious history book about women rulers of Jerusalem during the time of the Crusades, after references about help received from various academic persons, “…and my mum read the manuscript countless times.” That is the first time I have come across this term in a context of this kind. But that might have something to do with the familiar tone the writer uses elsewhere in this section, where she also writes “X has been brilliant in corralling me to get the manuscript (ready).” According to my understanding of the significance of the word ‘brilliant’ this does not quite fit the bill, but it seems that contemporary British usage of the word has extended its meaning considerably.

I acknowledge the fact that languages change over time, and since I have not been living in England, the land of my birth, for many years, this inevitably means that, despite my best efforts, I have not kept up with all the shifts and changes of the English language in the last fifty years. Nevertheless, I’m still having a hard time coming to terms with the limitations that my education in England some sixty years ago seem to have imposed on me.

Occupational Hazards

In conversation recently with a musician friend it suddenly dawned on me that because he is so knowledgeable about music, musicality and musicianship it is virtually impossible for him to enjoy a concert or recital in the same way that I, as an ignorant layperson, can. Anyone with extensive knowledge of a particular subject is at risk of being unable to enjoy a work of art or manufactured item if it falls within the sphere of his or her expertise. The application of rigorous professional standards as the yardstick by which enjoyment is reaped is bound to end in disappointment.

And so, a house-painter who is paying a social visit cannot help casting an appraising eye around his host’s house and drawing conclusions about the professionalism, or lack thereof, of the work. Presumably carpenters, bridge engineers, architects, gardeners and many others would find themselves in a similar situation. That’s tough.

I have noticed that this applies to myself, too, whenever I read a book or text in English. Having spent many years as a translator/editor, it is impossible for me to read a book without mentally correcting, editing or proofreading it. This generally tends to mean that I make a mental note of the fiasco but that is more or less where it ends, and I continue reading though with a more critical eye. This in fact happened recently, when someone gave me a copy of his recently published book. As I read the text, which was generally well-written, I noticed one or two slight grammatical errors or typographical flaws which marred the flow of the narrative for me.

I took up a pencil and began marking in the margin the points which I felt needed to be corrected, and when I had finished I summoned up my courage and showed the book to the author. Contrary to my expectations, he welcomed my remarks and at a later meeting informed me that he had incorporated most of them, in the next edition of his book.

One of the occupational hazards of having spent most of my working life dealing with both Hebrew and English means that I have a special sensitivity to language, whether written or spoken. Thus, in recent times I have come to abhor certain ‘slang’ expressions in both languages, such as ‘I was sat’ in English and ‘zotti’ (instead of ‘zot’) in Hebrew. Once upon a time this kind of terminology was reserved for cheeky teenagers or persons with minimal education, but nowadays it is widely used by all and sundry, including journalists, academics and members of the professions. I still feel physical unease when I hear them, but they are used so abundantly that I am afraid I will soon find myself accepting them as part of normal speech. And don’t get me started on people who say ‘Best regards from John and I.’ Would they say ‘regards from I’? Is it just ignorance, or has the English language abandoned every vestige of correct grammar? Another annoying habit of Hebrew speakers is to omit the ‘h’ sound in words. Here, too, it seems to be endemic throughout all social levels, and in my view it puts Hebrew speakers on a par with native Londoners, also known as Cockneys, whose level of education generally tends to be minimal.

Another strange usage is the substitution of ‘mum’ for mother. I have heard Prince Harry refer to his late mother, the much-mourned Princess Diana, as ‘my mum,’ which I take to express a son’s affection for his departed parent. Or perhaps it reflects his attempt to show that he is ‘just like everyone else,’ and ‘a man of the people.’ Be that as it may, imagine my recent shock when I read in the Acknowledgements section of a serious history book about women rulers of Jerusalem during the time of the Crusades, after references about help received from various academic persons, “…and my mum read the manuscript countless times.” That is the first time I have come across this term in a context of this kind. But that might have something to do with the familiar tone the writer uses elsewhere in this section, where she also writes “X has been brilliant in corralling me to get the manuscript (ready).” According to my understanding of the significance of the word ‘brilliant’ this does not quite fit the bill, but it seems that contemporary British usage of the word has extended its meaning considerably.

I acknowledge the fact that languages change over time, and since I have not been living in England, the land of my birth, for many years, this inevitably means that, despite my best efforts, I have not kept up with all the shifts and changes of the English language in the last fifty years. Nevertheless, I’m still having a hard time coming to terms with the limitations that my education in England some sixty years ago seem to have imposed on me.

July 27, 2023

La Vie Francaise

Just a few days in our village house in ‘La France profonde,’ namely, deepest France, are enough to soothe even the savage breast of people who have escaped from the turmoil and strife that characterise Israel today. We are not completely cut off from what is happening ‘back home,’ as the internet makes sure we are fed basic information on a daily basis. But at least we are spared hourly news broadcasts on the radio and the interminable ‘discussions,’ which inevitably turn into heated arguments on the TV.+And best of all, we are spared Binyamin Netanyahu’s nightly ‘statement to the nation.’

French politics are dull, or perhaps it’s simply our ignorance that gives us that impression. News broadcasts on the radio are few and far beteen, and in any case are given in rapid French which enables us to catch a word or name here and there, but c’est tout. As we do not possess a TV set that cuts out a lot of ‘noise’ with which we would otherwise have to contend.

There are, however, other obstacles to our mental health. Errands and encounters with officialdom. We had to engage to some extent with our French bank, but to our surprise the officials went out of their way to be helpful. Then there was the tax office, where we had to make a declaration about our house. There, too, the official (an attractive young woman) was extremely helpful, and even told us to go home and let her deal with the head office whose phone was continuously engaged. She assured us that she would get them later that day and inform us of the result. It worked.

The only fly in the ointment was the company providing our internet connection. France’s principal communications network provider is SFR, and that is where we went last year to be provided with a ‘boite’ (box) or router which we had to install in the house and to which our various computers had to be connected. Everything worked to our satisfaction, and when we left we returned the box to the company, sent them a registered letter ending our contract, and went home feeling confident that all was settled. However, the monthly payments continued to be deducted, and no matter how many letters we sent the company, they took no notice. On our second day in France we went to the SFR office in the nearby town to complain and demand a refund. This they firmly resisted, and were prepared only to provide us with a form letter for us to send to the client service department to end our contract. This we did, and promptly went across the road to their rival internet provider. Let’s hope the new system is more customer-friendly.

One phone call to a friend on our first day brought us to a concert in a church in a nearby village the next day. After an assortment of solos and duos by more or less obscure composers we were treated to a chamber performance of Mozart’s piano concerto no.9, given by a string quartet augmented by a cello and a contrabass, with a delightful young soloist, Fleur Lucchinacci. What a delight it was to hear (and see) the entire concerto played with the expertise and vivacity that Mozart requires. The church was full to capacity with an audience of villagers, farmers and sundry rural residents thirsty for good music and a good time was had by all.

And so it begins. We encounter friends and neighbours, invite them and are invited by them, adopt the easygoing ways (and dress) of the countryside, go shopping for fresh baguettes in the morning, attend the weekly fruit and vegetable market in the nearby village and generally slow down and take it easy. Soon some of our offspring will come to stay for a while, and we will enjoy showing them the delights of ‘la vie francaise.’

July 20, 2023

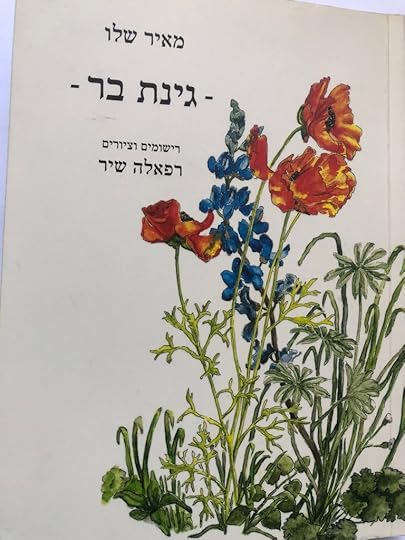

‘My Wild Garden’ (Ginat Bar) by Meir Shalev

From time to time I like to test my ability to read a literary text in Hebrew (the daily newspaper can hardly be called ‘literary’) by reading a book in that language. After all, I have been living in Israel for almost sixty years and have had to get to grips with Hebrew for the best part of my life.

The recent passing of the acclaimed Israeli writer, Meir Shalev, brought his last book, ‘Ginat Bar’ (Wild Garden) to my attention, and so I bought a copy and started reading it. After overcoming the barrier of the different language and alphabet, I found myself enjoying the account of the garden Shalev cultivated in Galilee, following a fairly strict regime in which he eschewed the cultivated plants and flowers that are customarily found in gardens and adhered only to those that grow wild in Israel. The book is divided into relatively brief chapters, each one dedicated to a particular wild plant or creature, or even an event, and almost all of them illustrated by a charming painting or sketch by Rafaela Shir.

The author’s slightly ironic and self-deprecatory style gives the reader the illusion that he or she is being drawn into an intimate conversation with him, allowed to share in his successes and failures, his attempts to tackle the unfamiliar and difficult terrain of the area surrounding his house and invest it with the natural beauty of the flora in which Israel abounds. The reader shares in the author’s pleasure at succeeding to germinate wild celandine and cyclamen, poppies, cornflowers and many other flowering plants. There are also interesting accounts of how he battled with the moles which burrowed underneath the soil, and how he eventually came to terms with their presence.

The book makes for easy reading, with relatively short chapters devoted to individual plants and trees, as well as to such varied subjects as weeding, rain, his cat, a wasps’ nest, various birds, spiders and snakes, to name but a few. Along the way, the author refers to and cites passages from the Bible and other ancient sources, as well as reminiscing about his childhood in Nahalal and Jerusalem, giving us insights into his family background, schooldays and life in general.

In the course of his account of life in Galilee and his labours in the garden Shalev also provides the reader with some interesting diversions from the main subject. And so, while describing the life (and death) of a lemon tree he goes into a long and fascinating account of how he makes the delicious liqueur known as Limoncello. He gives a detailed explanation of which lemons to use, how to prepare them and the entire (and lengthy) process by which the end-product is produced. A similarly long and detailed account is given of how to pick and pickle olives, adding amusing comments about other people’s reactions to them and repeatedly asserting the superiority of his product over all others. He also gives a long explanation of how he collects the seeds of the various wild flowers, whether in his garden or in the countryside, how and where he stores them, generally displaying a sense of purpose and satisfaction in his actions. I must admit that not all the names of the flowers in Hebrew were familiar to me, so that I had to resort to Google Translate from time to time to ascertain which particular flower or plant Shalev was talking about.

The book purports to serve as a guide to maintaining a wild garden, or rather an account of how Shalev maintains his own version of it, but in the final event it provides an insight into the character of a quirky individual who has made a reputation for himself as a talented writer but has lost nothing of the enquiring, intelligent individualism that reflects the essence of Israel’s ethos, history and development.