Marcia Meier's Blog, page 9

February 3, 2016

Excerpt from 'Face, A Memoir,' Part Eight

This is Part Eight of my memoir, Face, which tells the story of my being hit by a car and severely injured as a five-year-old. You can read the book from the beginning here. In this excerpt, I talk about my dad.

Part Eight

July 11, 1961 - Surgeon’s notes: Dressing change is done under anesthesia to reduce trauma to the patient.

I am lying in my hospital crib. Dr. Kislov and several nurses surround me, and the doctor is peeling away the dressing on my cheek and eyelid. Gauze sticks to my cheek. He pries it, loosening it with water, slowly pulling it away, minute by minute. My skin holds tight. I want to cry, but the nurses hold my arms close to my chest and say: “It’s okay. It’s okay. Stay still, stay very still.” I do not want to stay still! I want to push them away from my face. But the nurses hold me tight. I cannot move. So I cry. But I cry with my mouth closed, my lips pursed and my breath held, because that is the way Dr. Kislov wants it. He is the surgeon, the chief revisionist, and I have no say in this restoration project.

When I found Dad’s list, I thought, This is so like my dad. Meticulous, careful to record every expense and include everything, down to my blood-soaked panties. Oddly, one thing is glaringly missing: my mangled bicycle. I can’t imagine that he would leave that off. Maybe some kind soul got rid of it so my parents wouldn’t have to confront it, and he just overlooked it when he was making his tally. Perhaps it was just too painful to consider. I don’t know. But today I wonder about it. About whether he considered the cost versus the emotional toll. Whether in some way ignoring the bike allowed him to cope. I don’t think he would have blamed himself. That wasn’t like my dad. But he may have overlooked it if someone discarded it in an act of kindness. And when he realized it was gone, he might have decided it was too late to include in an insurance claim.

The amount my parents had to pay overall—$2,086.48—was the equivalent of more than $16,076 today. It was a lot of money. They struggled to pay the hospital bills, despite the insurance payments. They were fortunate to have the security of the family business. Even so, with four children to feed, mounting medical bills were a burden. Perhaps, in intimate moments, my mom and dad talked about how they would make it through. How they would pay for the Catholic education they wanted for all their children, the uniforms, the schoolbooks. They did what they could to make it work.

Mom sewed a lot of our clothes, and Molly and I always wore hand-me-downs. Dad worked six days a week and Mom, who had an English degree, substituted at St. Joe’s to make extra money. I was oblivious to much of it. But as I got older, though no one ever said it, I began to understand at some level that the financial struggle was my fault.

Fortunately, the dry cleaning plant offered a steady – and over time, growing – income. Dad often left the house before 7 in the morning, and returned just before 6, when Mom would place dinner on the table.

When we were young, my dad’s job was to give Molly, Chuck and me baths after dinner while Cherie helped Mom clean up the kitchen. Bath time always meant lots of splashing, submarining and water on the floor. He loved to make us laugh. And he laughed just as heartily – until Mom would call up from downstairs and scold us for taking so long. He’d pull the towels off the racks and say, “Okay, out!” Once we were in our pajamas, he’d oversee our prayers and tuck us into bed.

When we were small, he’d snatch our noses and hold them behind his back, laughing as we pointed to his hidden arm. He would often get down on the floor in the living room and romp with us, laughing and letting us ride on his back. My mother would yell if things started to get out of hand. Then he would say: “Okay, kids. That’s enough. Go help your mother.” And we’d head off to the kitchen.

I have struggled to bring my dad to the page. I don’t know why. Perhaps it is because he meant so much to me. He always was there, surrounding me with the sense that I mattered, that I was somebody worth loving. So many times since his death I’ve wished he was here to talk with, to discuss world events, or my job, or complain about one thing or another, to which he would always reply, “You have the power to choose how to see things, Marcia.”

He loved jelly beans, hard Christmas candies, and golf. He would stop on the street to pat the head of a stray dog. Would go out of his way to help an employee, lending money, advice, whatever was needed. He believed in God and Jesus and going to Mass every Sunday, and on that point he could be rigid.

He taught me to dance, though I could never get the hang of following his lead. To be honest, I never got the hang of following anyone’s lead, which some might regard as one of my many flaws.

He didn’t tolerate dishonesty. Once, when I was a teenager, he caught me in yet another lie about one thing or another. To my surprise, he told me to leave, to go away and not come back. We were standing in the driveway of our house near the lake, and I looked at him with disbelief. But then I realized he meant it. I turned, tears springing to my eyes, and I started to walk down the street away from the house. I had barely gotten a hundred feet away when I stopped and turned. He was standing in the driveway watching me. I ran back, sobbing: “Please let me stay. I promise I’ll never lie again.” He considered me for a moment, and finally said, “Okay.” I never told him an untruth again, until he was dying.

(To be continued...)

January 27, 2016

Discovering London and Ireland

Until two years ago, I had never been out of the United States beyond a sojourn to Ensenada, Mexico, and to parts of Canada, which in my mind don't really count. In 2012 I went to Costa Rica and stayed at my cousin's beautiful home on the northern Costa Rican coast for a month. It was there that I finished the first draft of my memoir, which I've been excerpting in posts on my blog (here is Part One, if you've missed them).

So I was literally giddy last fall when Rob and I traveled to London and then to Ireland for three weeks. Our transAtlantic flight felt like Christmas Eve to me, and the stewardesses and stewards must have sensed it because they presented us with a bottle of champagne upon our arrival at Heathrow. Everything seemed magical to me. I loved London. Loved its energy, its people, the Tube, the lovely little boutique hotel in which we stayed, the vintage double-decker bus tour we took, the theater district play we saw, the vast historical sweep of the buildings and monuments everywhere one looked. In just the few days we were there we shopped at Harrods, saw a Shakespearean play at the Globe Theatre, took a boat trip up the Thames, and visited the new Tate Museum. And it didn't rain a single time, despite all the rain gear we took along. We were in Europe from late September through mid-October; the weather was cooler, but the crowds were almost nonexistent. I would go back to London in a heartbeat, because there was so much we didn't get to see. But the purpose of our trip was to see Ireland.

The London Eye

The Cheesegrater

When we flew to Dublin on the fourth day, it was sunny and in the low 60s, a harbinger of the weather we encountered throughout our time there. Dublin is much smaller than London, but has its own charms. Our hotel was on the edge of the Temple District, which is the hot nighttime place brimming with bars and music venues.

The most impressive thing about Ireland is every corner has a pub, and every pub (almost) has a live band singing traditional music. We LOVED the immersion into Irish culture and music, and relished it as we traveled south and then up the west coast of the country.

St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin.

At a pub listening to traditional Irish music.

On the Jameson whiskey tour.

Next, Waterford and Kinsale.

January 25, 2016

Excerpt from 'Face, A Memoir,' Part Seven

Photo by Tony Hughes/iStock / Getty Images

When my dad gave me the blue folder, I was surprised, dismayed, curious about why he waited until I was getting married to give me something so concrete, yet so powerfully mundane. Why did he save it? I don't know, but I'm grateful he did. It contained this list. (Read Face, A Memoir, from the beginning here.)

Part Seven

Week of 6/17/61

C. Jeanne Roslanic, special nurse 7 nights........................................ $126.00

Ruth Fairris, special nurse 7 days......................................................... $88.50

Mildred Tayor, special nurse 7 days..................................................... $126.00

Ambulance ............................................................................................ $12.00

Clothes ruined, undershirt, t-shirt, shorts and pantie.................... $5.00

Mrs. Henry Medema, caring for children............................................ $10.00

Carol Black, caring for children............................................................. $5.00

Kathy Wirkutis, caring for children....................................................... $6.00

Housecleaning ............................................................................................ $5.00

Total .............................................................................................. $384.00

Week of 6/24/61

C. Jeanne Roslanic, special nurse 4 nights......................................... $72.00

Mildred Tayor, special nurse 3 days...................................................... $54.00

Ruth Fairris, special nurse 4 days.......................................................... $54.00

Mrs. Medema, caring for children.......................................................... $10.00

Carol Black, caring for children.............................................................. $6.00

Kathy Wirkutis, caring for children........................................................ $7.00

Housecleaning ............................................................................................. $7.00

Total .............................................................................................. $210.00

Week of 7/1/61

C. Jeanne Roslanic, special nurse 3 nights.......................................... $54.00

Mrs. McMann, special nurse 1 day........................................................... $18.00

Mrs. Medema, caring for children........................................................... $10.00

Carol Black, caring for children............................................................... $2.00

Kathy Wirkutis, caring for children........................................................ $4.00

Patty Wirkutis, caring for children......................................................... $1.50

Geraldine Green, caring for children..................................................... $3.00

Housecleaning ............................................................................................. $5.00

Total ................................................................................................ $97.50

Week of 7/8/61

C. Jeanne Roslanic, special nurse 3 nights........................................... $54.00

Mrs. Medema, caring for children............................................................ $15.00

Carol Black, caring for children................................................................ $4.50

Kathy Wirkutis, caring for children......................................................... $2.50

Patty Wirkutis, caring for children.......................................................... $1.75

Barbara Green, caring for children......................................................... $1.50

Total .................................................................................................. 79.25

Week of 7/15/61

Patty Wirkutis, caring for children......................................................... $13.00

Kathy Wirkutis, caring for children........................................................ $2.50

Geraldine Green, caring for children..................................................... $0.75

Carol Black, caring for children............................................................... $3.00

Total ................................................................................................ $19.25

Discharged from Hospital 7/22/61

Dr. Kislov .............................................................................................. $650.00

Dr. Crawford.............................................................................................. $195.00

Dr. Bond .............................................................................................. $150.00

Dr. Askam ................................................................................................ $65.00

Dr. Smith .............................................................................................. $105.00

Hospital Expense .................................................................................... $1,302.92

Total ........................................................................................... $2,467.92

Grand total ........................................................................................ $3,257.92

John Hancock Insurance paid Hospital ........................................... $834.94

John Hancock Insurance paid Surgery............................................. $336.50

Total cost ........................................................................... $2,086.48

When I found Dad’s list, I thought, This is so like my dad. Meticulous, careful to record every expense and include everything, down to my blood-soaked panties. Oddly, one thing is glaringly missing: my mangled bicycle. I can’t imagine that he would leave that off. Maybe some kind soul got rid of it so my parents wouldn’t have to confront it, and he just overlooked it when he was making his tally. Perhaps it was just too painful to consider. I don’t know. But today I wonder about it. About whether he considered the cost versus the emotional toll. Whether in some way ignoring the bike allowed him to cope. I don’t think he would have blamed himself. That wasn’t like my dad. But he may have overlooked it if someone discarded it in an act of kindness. And when he realized it was gone, he might have decided it was too late to include in an insurance claim...

(To be continued...)

January 21, 2016

Excerpt from 'Face, A Memoir,' Part Six

This is Part Six of my memoir, Face. I was hit by a car and severely injured as a child--my left cheek and eyelid were scraped away, and I endured fifteen years of surgeries after. Many years later, as I was getting ready to be married, my dad gives me a folder containing photos that force me to confront a time I had stuffed deeply away...(Read Part Five here.)

Twenty-four years later, as I sat on the concrete floor of a rented storage space and once again leafed through the files, I was instantly transported back to childhood, to when I was five. My hands shook as I sifted through the papers. And then I saw them. The photos. They were close-ups, taken a few months after the accident.

The left side of my face was red and raw, with ridges of skin built up in the middle of the left cheek like the spine of a mountain range. A piece of thick skin bisected the left eye, connecting the top and lower lids. I wondered if my dad had looked at the photos before he gave me the folder. Certainly he had seen them before, but did he consider how it would make me feel to look at them now? Or had he just put them out of his mind and not realized the impact they would have on me? Or perhaps this was his way of giving me back a part of my life that he felt belonged only to me, that I had to be the keeper now, of the story and all its attendant heartaches. Today, I believe he was giving me a gift, the gift of a past that I didn’t want to look at then, didn’t intend to look at ever. In a way, it was a gift of great love. Though I wouldn’t realize it until after he was gone.

As I sat on the concrete floor, I stared at that face, and let the tears come. Great heaving sobs pulled at my lungs and shook my ribcage. It was as if those pictures had the power to hold me hostage—that they had held me hostage for forty-five years. And I was reduced to a quivering, fearful child once again.

A few days later I took the photos out again. I could barely stand to look at them. They represented all the hurt, all the taunts, all the pain I had spent years stuffing away, convinced if I didn’t think about the accident and how it made me look, it couldn’t hurt me anymore.

I lowered myself to the floor. I wanted to be as close to the ground as possible; I feared I might collapse if I wasn’t. I peered at the first photo. It was taken from the front, and that little girl was staring straight at the photographer. Her eyes appeared to be the eyes of an old soul, someone who has suffered and survived. There was something in the eyes of that child, that five-year-old, that was way beyond her years. Way beyond the pain and suffering, beyond the here and now, planted firmly in the Divine. Sure of herself and sure she would survive, no matter what. The second photo, taken from the left side, was entirely different. It was of a small child afraid, terrified of being hurt, of being abandoned to the nurses and doctors once again, of being left in the hands of people who didn’t care, or didn’t seem to. That child’s eyes reflected such a deep sadness, a grief so profound I wanted to hold her, reach out to her across the years and make her safe. But I couldn’t. Not yet.

(To be continued...)

January 17, 2016

Excerpt from 'Face, A Memoir,' Part Five

This is Part Five of Face, A Memoir. When I was five years old I was hit by a car and lost my left cheek and eyelid. It was the beginning of nearly two dozen surgeries over fifteen years. In this section, I decide to see a therapist when, as an adult, my life seems to be falling apart.

(Part Five)

I am sitting on a white overstuffed couch in the Santa Barbara office of a therapist a friend recommended. South-facing windows let in filtered light from the late morning sun. Japanese paintings hang on the cream-colored walls, creating a sense of serenity and intimacy. A box of tissues is tucked behind the lamp on the side table, within easy reach. Michael sits in a straight chair in front of me, his long legs tucked under. His square, tanned face framed by waves of blond curls. We are talking about self-esteem.

“I don’t have a problem with self-esteem.”

“Yes, you do,” Michael says.

I am stunned. “No, I don’t.”

“Yes, you do,” he repeats, more emphatically.

I look out the window at the jacarandas in bloom, their graceful purple flowers nudged by a gentle offshore breeze.

I’d always thought of myself as confident, secure in my self-image, strong and independent. I was a successful journalist – had been editor of the editorial pages of a medium-sized daily newspaper and a recognized leader in the community. I did not lack confidence in my abilities.

But that wasn’t what he was talking about.

When I first went to Michael for help, it was because I suspected – and feared – my marriage of twenty-four years was over. After a month of weekly meetings, he suggested joint counseling with my husband. But after nearly six months, we were making little, if any, progress. So we stopped, and I returned to individual sessions with Michael.

Now here I was, sitting in Michael’s office wondering what had gone wrong. With my marriage. With my career. With my life.

“Talk to me about your scars,” Michael said.

“What do you mean?”

“How did you get them?”

I shrugged. Gave the rote response, something I had spent years perfecting: “I was hit by a car when I was five. I was nearly killed and lost my cheek and my eyelid. I underwent twenty surgeries over the next fifteen years.”

“How do you feel about that?”

How did I feel? I didn’t feel. I hadn’t felt about it in years. I hadn’t thought about it in years. But the more Michael and I talked, the more the memories flooded back. Then I remembered a folder my father had given me just before I got married.

My mom and dad were visiting me in Redding, where I was a reporter for the newspaper, and I was sorting through clothes in my bedroom when my dad knocked on my open bedroom door.

“Hi, Dad. Hot enough for you?” It had to be 102 already, and it was midmorning.

He smiled. “I have something for you.”

He sat down on the bed and patted the spot next to him. I plopped down.

“I am so proud of you,” he started. “Now you’re getting married, I guess it’s time I gave you this.”

He held out a thick, faded, dark-blue folder.

“What is it?”

I opened the folder and was surprised to see dozens of hospital invoices, insurance documents and doctors’ bills, all dated from the 1960s and ’70s and all carefully marked “paid” in his distinctive hand.

“Oh my gosh, Dad.”

He had saved and noted each bill, each surgical procedure, each hospital stay. As I leafed through, I came across a yellowed photo envelope and opened it. That was when I saw the photographs for the first time. I looked for only a moment, then shoved them back into the envelope and put it back into the blue folder.

There was an awkward silence.

I didn’t know what to say. Why had he saved all these things? And why did he feel it was important to give them to me now?

Finally, I mumbled, “Thanks, Dad.”

He patted my leg again, and stood to go.

“I think your mom’s waiting to go shopping,” he said as he walked out of my room.

“Okay.”

I sat alone for a few minutes. I felt confused and overwhelmed, as if he had shown me a film clip from my childhood, one I hadn’t expected and didn’t want to see.

Then I walked over to the dresser and put the folder in the bottom drawer, under some old jeans. I gathered my purse and my shopping list for the wedding and walked out to the kitchen where Mom was just finishing putting away the breakfast dishes.

“Ready to go?” she asked. I nodded, and as we left, I put the folder out of my mind.

(To be continued...)

January 14, 2016

Excerpt from 'Face, A Memoir,' Part Four

This is Part Four of Face, A Memoir. In Parts One, Two and Three, we find out I have been hit by a car at the age of five and have lost my left cheek and eyelid. After five weeks in the hospital, I come home, and my mom and dad prepare my sister and brother for a Marcia whose face was ravaged.Part Four

“Marcia is coming home this afternoon, and she looks different than she did,” my mom explained. “You shouldn’t be afraid when you see her. She’s still your sister. She’s still the same Marcia.”

But I wasn’t.

I looked grotesque. A thick fleshy string connected my upper and lower eyelids. There was a gaping hole underneath my left eye where the skin had been torn away. A red ridge of scar tissue ran the length of my left cheek, with thinner spines spreading out like a spider web toward my nose and ear. A jagged pink scar jutted down from my lower lip toward my chin.

How did they respond to my face? Chuckie was so little, only three. But Cherie was ten, and had seen me on the street, my face torn away. She remembers that Mom told her she would have to help a lot, because I would need a lot of care. But she doesn’t recall being surprised or shocked at how I looked.

“I think I was sad,” Cherie said, “and I was prepared to help with whatever Mom needed.”

A few weeks after I came home, we went shopping downtown.

Mom didn’t often take us downtown. It meant putting Molly into a stroller and tethering Chuck to it with a harness. I was allowed to walk freely, but liked to go off exploring when mom wasn’t looking. That often led to frantic searches and stern scoldings once she found me. But off we went.

We were in Hardy-Herpelsheimers, then the nicest department store in Muskegon. Mom was looking at some dresses and I was uncharacteristically clinging to her. A woman came around one of the displays with her two children and stopped short.

“Oh, my God,” I heard her say. She turned and pulled her children away. “Kids, don’t look at that little girl.”

My mom didn’t say anything, just pulled my head in close to her and held me there, in the middle of the store. We left then, without buying anything, and walked home.

Now that I am a mother, I wonder at her ability to withstand it all. I look at photographs of myself after the accident, and I think, could I have done this? How did she feel, knowing her daughter would be disfigured probably for her entire life? Did she hope I might die and escape the cruelty, the stares, the laughter, the pointing? I can’t imagine. She had pushed the grief from the two lost babies deep within. When she was alone with her thoughts, when she kneeled beside her bed to pray every night, what did she pray for?

I walk on the beaches in Santa Barbara almost every day, watching the tides come in and go out, changing the landscape from one day to the next. Some days the beach is thick with sand stretching from the shoreline to the cliffs. Others the sand is washed away, exposing barnacle-encrusted rocks, sea anemones and an occasional starfish. My Australian shepherd frolics in the waves and plays with the other dogs on the beach. And I think, How is the self built? Like the changing beachscape, we are shaped and formed by forces outside of us. Surely the self is altered by experiences, by perceptions created out of circumstance. What happens to the self if face and body are transfigured by happenstance? If that self is in early formation, a young child of five, the self may be more radically affected. After the accident, my identity evolved into that of a scarred child, a child whose face repulsed people. It wasn’t long before I knew that I was someone to be avoided, that my face was a frightening visage, even for adults. And while I knew my family knew and loved me, I also was certain no one else could possibly see and appreciate the self I was within.

(To be continued...)

January 12, 2016

Remembering My Dad...

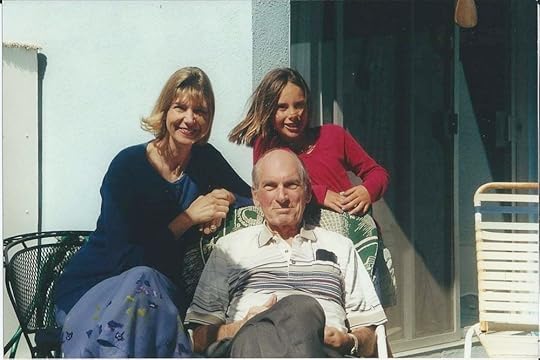

With my dad and my daughter, Kendall, just two weeks before he died in May 2000.

My dad’s birthday is today. He would have been 90 if cancer had not taken him. In my memoir, Face (see excerpts here), I write that I had a hard time bringing who he was, and what he meant to me, to the page. It was a struggle, and I still don’t feel I did it very successfully.

Memory is a fluid thing. It moves and undulates and morphs with time. I knew him so well, knew that he loved jelly beans and golf, that his Catholic faith formed him and sustained him, that he loved my mother. That he loved me. That his love is perhaps the reason I was able to overcome the trauma I experienced throughout my childhood. But in the writing, I struggled to explain how very much he meant to me. Recounting the memories I have of him, it felt soon as if I were just reciting a long list, without really bringing him to life.

Perhaps my memory—my psyche—doesn’t want to go there. It’s too painful, just like all the hospitalizations and surgeries. I couldn’t have determined which hospitalization happened on which date without the notes from my surgeon. Which time was I made to lie naked in a hospital crib under a large oxygen tent? Which time did I awake and believe I was somewhere other than the hospital, which frightened me to the point the nurses had to get permission to lift a corner of one of the bandages on my eyes so I could see? Which time(s) was I made to lie for hours, my arms strapped to the bed, as plasma dripped into my veins?

We strive to create a narrative of our lives that makes sense, and when events don’t make sense, or fall along the story line, we make things up. I am sure I am guilty of that. But the individual events I write about in my memoir are as concrete and vivid as if I were living them today. The memories just as jagged and piercing, just as white-hot with emotion, as if my insides were searing with grief.

I wonder sometimes how long trauma lingers. I spent many years stuffing it into a very deep place, thinking if I did it would no longer hurt me. How wrong I was. Excavating that past has been devastating. Also clarifying, opening—my chest feels cracked open; I am breathing again, but damn it’s painful.

How I miss my dad, and wish he could be here to see his daughter step into her life, finally, authentically. Terrifyingly.

January 11, 2016

Excerpt from 'Face, A Memoir,' Part Three

This is Part three from Face, A Memoir, which I am serializing in posts on my blog. Here are Parts One and Two. The memoir is about my struggle to come to terms with a childhood trauma that haunted me well into middle life. It has taken me many years to write this, and I am revising it as I post pieces of it online. I welcome your thoughts and feedback.

Part Three

July 6, 1961 - Surgeon’s notes: Patient—a five-year-old girl—presented in the emergency room on June 17 with severe lacerations and subdermal abrasions on the left side of the face and upper chest. Primary concern was stanching blood loss and saving the left eye. Emergency closure of facial wound required pulling together tissue from both sides of the cheek. Pressure bandages applied. Loss of upper left eyelid and portion of lower left lid required fashioning of tarsorrhaphy to protect the eye.

I wake and I can’t see. My face itches. My ears itch. I am desperate to scratch my ears. I can’t move my arms! Why can’t I move my arms?

My mom’s voice comes to me. Soothingly, I hear her say: “It’s okay, Marcia. It’s for your own good.”

Every day for five weeks she came to the hospital and sat by my bedside, waiting for me to wake, enduring my fearful tears when I did, watching the nurses give me shots and adjust my bandages, listening to my screams when the doctors changed the dressings. Did she retreat? Crawl into a cavernous place of grief – perhaps denial – to deal with the shock, the pain?

Mrs. Medema and several neighborhood girls took turns babysitting the other kids while she was at the hospital. At the end of the day, she’d go home to her three other children. I know friends and family members helped out. But what was it like for her to watch me cry, seeing me bloodied and bandaged, knowing I was terrified, knowing I suffered, knowing there was nothing she could do but try to soothe me? Then going home to three young children who also needed her attention. She was overwhelmed, emotionally and physically. And still she came and sat. Sat with her knitting, absently crossing needle over needle, moving the yarn from left to right, right to left. I see her deft hands, her pointer fingers crisscrossing each other with each stitch, her mouth a set line, her brow furrowed. The ball of yarn unfurling.

Over time, she shut down. Sat and patted my hand as they pulled stitches from my face, or placed another needle into my arm, or held me down for another change of dressings. Emotionally, she left. Pushed her feelings to a deep place so she could manage daily life. How could she not? But it didn’t start with me.

His name was Patrick, Ricky for short, their second-born. Cherie was two and Ricky eight months when my parents were invited to go away with another couple for a weekend of sailing. Their friends Barb and Harvey Nedeau offered to take care of the kids. When they dropped them off, my mom was fretting. She wanted Barb to make sure Cherie had her blankie at night, that Ricky got his bottle at five and again just before bed.

Barb reassured her.

That night, Barb set up a vaporizer near Ricky’s crib so he could breathe easier. Sometime in the middle of the night, he pulled the cord and the vaporizer over into the bed, scalding his body with boiling water. The Nedeaus raced Ricky to the hospital. My parents rushed home. Ricky died two days later.

A year and a half later, my mom was expecting. It was winter and the streets were icy. My grandmother was driving with my mom and Cherie, heading downtown to shop. As she negotiated the slippery streets, my grandma noticed a large spider above her head on the visor. As she watched, it dropped down near her face. She swatted at it, and as she did the wheel turned to the right and the car left the road. As Cherie bounced in the back seat, the car ran up the guy wire of a telephone pole and overturned. Mom was thrown out of the car. Cherie and my grandma were unhurt, but Mom suffered skull fractures and ended up in the hospital for several weeks. The baby, Robert, was born several months later, but died within hours. Mom knew she would lose him, because she hemorrhaged through the rest of the pregnancy.

The boys are buried together in the Muskegon Catholic Cemetery.

Before I was released from the hospital on July 23, my mom and dad gathered Cherie and Chuck in the living room.

“Marcia is coming home this afternoon, and she looks different than she did,” my mom explained. “You shouldn’t be afraid when you see her. She’s still your sister. She’s still the same Marcia.”

But I wasn’t.

(To be continued...)

January 9, 2016

Excerpt from 'Face, A Memoir,' Part Two

This excerpt from my book, Face, A Memoir—is Part Two of many parts to come. You can read Part One here. It is about my struggle to come to terms with a childhood trauma that haunted me well into middle life. It has taken me many years to write this, and I am revising it as I post pieces of it online. I welcome your thoughts and feedback.

Chapter One, Part Two

As Muriel and Roscoe approached the stop sign, my ten-year-old sister, Cherie, was walking home from her friend Marilyn Green’s house. Just as she turned the corner toward our house, she noticed a car driving slowly, and heard a distinct scraping noise, as if something were being dragged underneath. People on the sidewalk started to scream, “Stop! Stop!” As she watched, Cherie realized my new bike was trapped under the car. When the sedan stopped it was nearly in front of our house. I had been dragged, caught with my bike under the car, for nearly two hundred feet.

Cherie ran to the front of the car and looked underneath. I was lying on the street under the driver’s side. The bike was stuck under the carriage; I was still holding the handlebars. The left side of my face was missing.

Cherie ran into our house. Mom was in the front hallway, talking on the phone with my grandmother, Mimi.

“Marcia’s been hit by a car!” Cherie screamed. Mom dropped the phone and ran out to the street. My sister picked up the phone and shouted, “Marcia’s been hit by a car and she’s dead!” She hung up the phone and ran after Mom.

Mom’s morning had begun early. Dad was gone by 6:30. Mom woke three-year-old Chuck and Molly, the baby. She helped Chuckie get dressed and brush his teeth. She got a bottle for Molly, and cereal for Chuck. With four children and two adults in the house, our cramped kitchen often seemed like Grand Central Station. A large chrome table with a marbled yellow top crowded one corner, surrounded by five chrome chairs with padded yellow vinyl seats and a highchair. The cupboards were dark, the appliances spare. A small window above the sink, decorated by a frilly white lace curtain, looked out onto the side yard. Once we were all fed, Mom sent us out to play and cleaned up. She was petite, though thick around the middle with the pudgy remnant of six pregnancies. Her dark-brown hair was clipped short and styled, and her deep-brown eyes were accented with thick, black brows. Mom put Molly down for a morning nap and started some laundry in the basement. The telephone rang. It was my grandma, calling to check in, as she did every day. They fell into an easy conversation.

Suddenly, Mom heard yelling outside, people screaming. She was about to tell my grandmother to hold on when Cherie burst through the front door.

“Mom, Marcia’s been hit by a car…”

She didn’t hear any more. She dropped the phone and ran to the street. As she drew near the car she saw the blood. She saw my bicycle. She felt her chest tighten, and thought, “not again, not again….dear Lord, don’t let it happen again…”

By midmorning, Dad had made his rounds of the dry cleaning plant and stores and was pressing pants in a back room where one of his workers, Carl, was operating the dry cleaning machines. Hot pipes and machinery hissed and moaned. Dad was wearing shirtsleeves; but Carl was wearing a tank top already wet with perspiration. It was insufferably hot, and big fans droned and blew stagnant air from above. The smell of cleaning solvents permeated the plant. When the phone rang, it was Judith, a longtime Meier Cleaners employee, who brought Dad the news.

“Bob, there’s been an accident,” she said. “It’s Marcia. Go to Mercy. They’re taking her there.”

He dropped the pressed trousers and rushed through the plant, careful to duck under the pipes and conveyer racks that hung low from the ceiling. His Ford station wagon was parked in the back alley. On the way to the hospital, all he could think was, “Please God, not another baby. Not Marcia.”

What is a face? Eyes. Nose. Mouth. Cheeks. Chin. Forehead. An invitation. Or a warning. A reflection. Or a misrepresentation. The surface of a still pool, or a raging creek. Does a face say anything about a person? Or everything? If a face is destroyed, does that person change? If you rebuild a face, can you rebuild a life?

When mom got out to the street, the car had been backed away. Someone had lifted the mangled bike off of me and laid it aside. Mom cradled my bleeding head until the ambulance arrived. A neighbor took Cherie and Chuck inside to comfort them and check on Molly. After the ambulance left, Mrs. Medema took her garden hose and washed the blood from the street.

At the hospital, the family prayed silently in the stark white waiting room, sprawled on avocado-green couches and chairs.

I have often thought of my mom in those hours, drenched in my blood, holding vigil with my dad, reeling from the realization she may lose another child to an unspeakable tragedy.

When our family physician, Dr. William Bond, saw me in the emergency room, he doubted I’d survive. My cheek was scraped to the bone, my left eyelid was missing, and the bottom lid was carved away from the eyeball, though the eyeball was intact. There were deep cuts and scrapes on the rest of my face and upper chest. I had lost a lot of blood. Emergency room doctors worked feverishly to stem the bleeding. They inserted intravenous lines into my arms as they frantically tried to keep my heart rate and breathing stable enough to take me into surgery.

One of the three doctors who worked on me was a thirty-nine-year-old plastic surgeon who happened to be at Mercy when I was brought in. Dr. Bond asked him to see me as a personal favor. Dr. Richard Kislov was a brilliant surgeon who immigrated to the United States from Germany. He was known best for re-attaching severed limbs, a particularly handy skill in Western Michigan where automotive factories were common. Dr. Kislov and the other doctors worked for hours, pulling skin together to fill the vast hole that had been my left cheek. Somehow, they formed a bridge of skin to cover my left eye, sutured the wounds on my chest and bandaged my head. They kept me alive

There is a place one can go, a dream state where it is easy to imagine that whatever your five senses may be telling you, whatever sounds you hear of oxygen tanks or rustling uniforms, whatever piercings of your skin, or peeling of gauze from your torn face, whatever smells of alcohol or ether you sense, they are not to be trusted. The only true thing, in that liquid place, is the comfort of remembering, of feeling the warm encirclement of your dad’s arms, of knowing the drone of the box fan in the window down the hall means there will be at least a slight breeze to offer relief from the sticky heat, that your mom’s voice will always be there, softly assuring, so satisfying, so deeply resonant. All reality fades into that place, and holds you suspended and safe.

Was that deep-water suspension induced? Or does the mind take over, knowing the psyche may not be strong enough to comprehend, and so it protects by obfuscating, by creating a separate reality? How long did I lie there, blissfully unconscious? Days, weeks – it could have been a heartbeat. But when I awoke, all that amniotic protection evaporated into the harsh whiteness of a hospital room.

I didn’t know where I was. My head and eyes were wrapped in bandages. My hands tied to the sides of the bed. I did not feel any pain, but my head was heavy and I felt woozy. I was afraid. People around me smelled of antiseptic and starched clothing.

I heard my mom’s voice. She said, “We told you never to cross the street without looking.”

But I did. I looked both ways.

(To to be continued...)

January 8, 2016

Poem—In the Parking Garage

In the Parking Garage

(After Philip Levine’s “The Two”)

She opened the door and got out of the car,

walked briskly around and toward the

parking structure stairs, certain they

would be late. But it didn't matter. He

was trailing behind, as usual. There

was little said between them,

too little said for too many years,

too grief-stricken at the prospect

of there no longer being a them.

What unsaid things have passed between them,

what unthought thoughts have gone unbidden,

what fears unexpressed, what sorrows suppressed

in the face of exposure, of distrust.

The distrust that destroyed them. She stopped

and waited for him to catch up. The parking

garage waited in silence, too quiet for

comfort, too cold for a moment that might

allow them to stop and remember.

The years have passed without understanding,

without recognition, without the knowledge

that would come with too high a price for either.

Now the parking garage is silent. They have left,

left behind, left in a lost time that neither

can quite grasp again, time they would both grasp desperately

if they could.