Phil Elmore's Blog, page 21

March 3, 2014

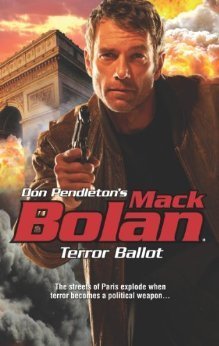

SuperBolan: Terror Ballot

My 18th novel for Gold Eagle/Harlequin in the Mack Bolan, Executioner, and Stony Man series is “Terror Ballot.”

My 18th novel for Gold Eagle/Harlequin in the Mack Bolan, Executioner, and Stony Man series is “Terror Ballot.”

When France’s presidential elections are hijacked by terrorists, violence erupts on the streets of Paris, fueling extreme antiforeigner sentiments. The chaos feeds votes to the ultraradical candidate, but intelligence indicates the attacks may be the ultimate propaganda tool. Soon, shock waves reach America, destabilizing foreign policy and U.S. interests in Europe.

Mack Bolan answers the call of duty, launching a surgical strike against the powerful, skilled radicals carrying out the slaughter. Dodging the triple threat of police corruption, political extremism and the bloodlust of trained killers, Bolan razes the terrorist strongholds. As the city of light bursts into a blaze of cleansing fire, the Executioner casts his vote for the terrorists’ blood—and an end to their deadly campaign.

Terror Ballot hits the shelves on 4 March, 2014.

February 27, 2014

Episode 09: “Goldilocks”

[image error]Peyton sat in the lee of carefully tended acoustic trees. The growths were genetically engineered to dampen sound and screen the playground from view. This was an upscale, gated neighborhood, accessible to Peyton and Annika only because the perimeter wall sensors required maintenance. Scaling the wall had become a pastime in itself, for Annika, who giggled and clapped whenever he hoisted them both over the barrier.

He had suggested that he wait beyond the wall while she played, knowing how out of place he would look. But Annika would not hear of it.

“That’s why I bought you your clothes, Daddy,” she told him. “So we can go out and do things together.”

Staring down at the exercise shirt with its trendy logo, he had been dubious. “This won’t fit.”

“It stretches, silly,” she told him. “To show people your muscles. That’s why people where them. You’re just a big exerciser, that’s all. Tell people you’re a personal trainer. There were lots of personal trainers at the exercise place on the concourse. Some of them were almost as big as you.”

“Really?”

“Almost.”

That had ended the argument as far as his daughter was concerned. And now Peyton sat in the shadows of genetically engineered privacy trees, cross-legged and hunched to disguise his mass. There were a few other parents milling about the park, but not many. There were several robot minders, one of which someone had draped in a rain pancho. There were a pair of camera drones floating overhead in lazy circles, drifting on carbon-fiber turbofans. Peyton recognized the brand, if not the model. The drones had been everywhere in the prison yard, watching from above, missing nothing.

The children of the wealthy wore brightly colored clothes of resilient, often reflective fabric. Annika had chosen her wardrobe well. At a distance, except for the flash of her blonde hair, she was indistinguishable from the other boys and girls. The age range seemed to run from three or four years to roughly Annika’s twelve. There was one boy who seemed a year or two older, but it was hard to tell. He was very large compared to the others, a stevedore among grazing goats.

He chuckled, despite himself, surprised by his own small joke. Goats. Kids.

Annika looked to him periodically, as if to reassure herself that he was still there. Apart from that, she left him alone. He had never had to explain to her the danger in calling attention to him. His presence in any open space was vulnerability enough.

The sky was very blue. Birds sang in the acoustic growths. The breeze cooled his skin. For no reason at all, experienced the urge to close his eyes. To smile.

It was a feeling utterly alien to him. He shook it off.

Playground equipment had not changed since his own childhood. There were swings. There were slides. There was a pit of crystalline grit, carefully sanitized, in which the children dug holes with small entrenching tools, or built spires using a heavy electric wand that temporarily hardened the outer layer of “sand.”

He watched for a long time, feeling ill at ease. Annika built towers on top of towers, then smashed them, smiling all the while. The crystal grit did not stick to her clothes.

One of the parents drifted toward Peyton’s spot. He was middle-aged, of decent mass and height. His hair was brown and thinning. Peyton tensed. Was this a trap? An attack?

The man nodded. “Hey,” he said. From his glossy windbreaker he produced a vapor tube. The end of the tube glowed blue when he drew on it. He extended the oblong plastic pack to Peyton.

“No thank you,” said Peyton.

“I almost didn’t see you there,” said the man. “Anybody’d think you were dressed to hide.” Peyton’s shirt and workout pants were dark blue. “I wasn’t thinking,” said the man, wagging his vapor tube. “Obviously a health guy like you wouldn’t.”

Peyton wasn’t sure what response to make. He offered none. When his visitor began to eye him strangely, perhaps finally picking out Peyton’s true size in the shadows, he said, “I’m… a personal trainer.”

“Right,” the man said brightly. “That makes sense. I’m Jim, by the way.”

Peyton grunted something that was not a name. Jim nodded again as if he’d heard.

“Which one is yours?” said Jim.

Too many questions. Peyton jerked his chin vaguely in the direction of the playground. Jim was not paying attention. He pointed to the large boy, the one Peyton had noticed before. “That’s my Jim Junior,” he said. “He’s all-district for laneball this year.”

Peyton grunted once more.

Jim Senior, proud father of Jim Junior, finished his vapor tube and dropped it casually in the grass. He took a second from the pack and ignited it.

Jim Junior was now talking to Annika. Peyton’s daughter was digging a trench around her latest crystal spire.

Annika said something, gestured toward the spire. Jim Junior walked to her, snatched the shovel from her hand, and cut the spire in two. His laughter drifted to Peyton’s vantage. Annika shook her finger at him furiously. Peyton could imagine the scolding. Satisfied, Annika walked away, toward the nearest slide.

“Boys,” said Jim Senior. “Full of energy.”

Jim Junior pursued Annika. When she climbed the slide, he followed. When they were both at the top, he shoved her.

Peyton surged to his feet. Annika rolled down the slide, landing in a heap at the bottom. Peyton checked himself. She was already getting up.

Jim Senior chuckled. He did not turn; he had not seen Peyton stand. “I think maybe Junior is sweet on Goldilocks there,” he said.

Annika walked back to the sandbox. Her pace was deliberate. When she got to it, she turned and fixed Peyton with a look. He met it. When Jim Junior arrived, he shoved Annika again, knocking her into the grit. She very deliberately reached out, grabbed the electric spire wand, and clouted Jim Junior across the face. He went down. She continued to hit him with the wand.

“Hey!” Jim Senior shouted. He went to join his son, but Peyton was behind him now. A heavy hand the size of a cycling helmet grabbed him around the neck. He sputtered.

“You move,” whispered Peyton, “and I’ll change your life forever.”

Jim Junior was squalling now. Annika looked to Peyton again and then resumed her methodical beating. Her blows were not particular hard, but the wand was heavy and she was persistent. It only took a few minutes for Jim Junior to curl into a ball, sobbing. Deliberately, Annika placed the wand in its receptacle in the enclosure wall.

“Take your son,” said Peyton to Jim Senior. “Say nothing to the girl. If I ever see you again, you will spend the rest of your life drinking your meals.” He shoved Jim Senior forward, releasing him. The man wasted no time. He did not even look at Annika as he hurried to flee the playground with his boy.

Annika walked over, slowly, unsure. He nodded to her. “We’ll have to go,” he said. “It will be a little while before we can come back.”

“I know,” said Annika. Peyton stood and she took the edge of his hand. As they walked from the playground, she said, “Daddy?”

“Yes, Annika?”

“Did I do okay?”

Peyton stopped walking and looked at her. “Were you angry?”

She thought about it. “No,” she said. “Not really.”

“Did you want to hit him?”

“No.”

“But you did,” he said. “A lot.”

“I had to,” said Annika. “I had to make it so it was no fun for him.”

Peyton smiled at her. He knelt and, very carefully, hugged her. She disappeared within his arm.

“Then you did right,” he told her. “You did exactly right.”

February 26, 2014

Technocracy: Bitcoin Breakdown

My WND Technocracy column this week is about the dangers of what is fundamentally an imaginary currency.

There IS no bitcoin. It is code in a computer.

When bitcoin exchange Mt. Gox mysteriously closed its doors and took its customers money, this raised serious questions about the future viability of bitcoins as a digital medium of exchange.

Read the full column here in WND News.

February 20, 2014

Episode 08: “Authority”

[image error]“Just leave it in the bin,” said the clerk. “Everybody’s been in a state since the Warden was killed.”

Neiring did not know what to say to that. He let the clerk check his sidearm and his stun baton. The administrative wing was close to bedlam. Investigators from the Office of Government Oversight were tearing the place apart, cataloging individual circuits in the computer network and sifting through the internal database. At least, that was what Neiring assumed they were doing, based on the equipment he saw. Not one of the workers stood still long enough for him to get a good look.

Past the administrative hub, he took the lift to the lower level, where the wall panels told him the archives were located. There was less chaos here, but he saw several OGO personnel moving in and out of the digital stacks. A knot began to form in Neiring’s stomach.

“Chip,” said the attendant behind the archives desk.

Neiring offered his right wrist. The attendant wanded him and read his pertinents.

“Neiring,” said the inspector. “I’m here to—”

“So it says here,” the attendant said. He yawned silently into his hand. “Please be quick, Inspector. We’re in the midst of an audit.”

“I need the files on Peyton, Ian W., serial number 0341674.”

That got the clerk’s attention. He looked up. “I suppose you’ll want all the ancillaries, too.”

“You suppose correctly,” said Neiring. The clerk’s attitude was beginning to grate. Before the man behind the counter could speak again, however, footfalls rang on the poured stone floor. The man who approached was wearing polished, silver-tipped boots.

Neiring checked the urge to bolt. The man before him looked like a corporate headhunter. He was all angles and hollows, wrapped in a black leather suit that seemed a size too large in the shoulders. A silver gunbelt was strapped across his belly, the grip of the weapon close to the buckle.

“VanClef,” said the man in black leather. “Intelligence.”

“Neiring,” said the inspector. “I’m—”

“I know,” said VanClef. He wore black leather gloves over long, slender digits. One index finger now hovered above Neiring’s chest. “And you, Inspector Neiring, are a bit far afield for a truancy report.”

Neiring felt his jaw drop. “I…” he tried again.

“You were assigned erroneously,” said VanClef. “The truancy report your office received for Peyton, Annika M., should have been shunted to my office. Ms. Peyton is next of kin to a dangerous death-row fugitive. But you know that. I pulled your travel records. You’ve been all over Hongkongtown, following leads on the Peyton case, trying to connect our escapee to murders in the privateer fringe. Yes?”

“Yes,” Neiring said. “But—”

VanClef waved a gloved hand. “Don’t think your efforts are not appreciated,” he said. His tone was greasy. “Would that all government employees had your initiative. Assigned to locate the truant Ms. Peyton, you tracked her here… I assume through her use of public transit?”

“Yes,” said Neiring. He did not try to say more.

“Then, of course, you learned of her father’s escape. Clearly, you are not stupid, Inspector; you see the connection. We are working on the theory that the elder Peyton, who has been cooperative for more than a decade while awaiting execution, lost his nerve when he considered that his daughter might be watching.”

“Respectfully, Agent VanClef,” Neiring said, more loudly than he would have liked, “none of that makes any sense. I’ve watched the logs. Warden Richards and Peyton had some kind of agreement between them. I’m trying to learn what that was. I’m also trying to determine exactly what Peyton is. His file indicates no synthetics.”

“Ian Peyton is not an Augment,” said VanClef. “Not in the traditional sense. He is certifiably human… although, on paper, that description does not do him justice. It’s what the criminal syndicates call a bag-job. He’s loaded with extra adrenal glands, a few hormone regulators. Enough to bulk him up and inure him to pain. It’s nothing special. A biological parlor trick.”

“That’s not what it looks like on the logs,” said Neiring. “After leaving the gallows chamber he fought his way through another dozen armed guards to escape this prison. That escape includes punching his way through two interior fences and the exterior wall. The robot guards at the tramway never stood a chance. He smashed them to pieces.”

“That’s all very colorful,” said VanClef. “I imagine the distraction must be a desirable one. Why else would you be trying to find this pair in Hongkongtown?”

“They’re in the privateer zone,” said Neiring. “I’m certain of it. And Peyton has killed several times since escaping. I recovered a strand of Annika Peyton’s hair at one of the crime scenes.”

VanClef reached out and put a hand on Neiring’s shoulder. His grip was cold. “No,” he said. “You didn’t.”

“Excuse me?”

“Effective immediately, Inspector,” said VanClef, “this case does not concern you. The Peytons are the subject of a Government Intelligence operation. You will immediately cease and desist in any actions relative to the identification, location, or attempted apprehension of Ian and Annika Peyton. They were never here. You were never assigned. You have never heard of either of them.”

Neiring flushed. “You don’t have the unilateral authority to—”

VanClef’s grip became a vice. Neiring felt air escape his lips. Pain shot through his shoulder and he fought to keep his feet. “But I do,” VanClef said. “Don’t doubt me, Neiring. People get killed in Hongkongtown all the time.” He released the inspector, causing Neiring to bleat in relief.

Without another word, VanClef turned on his heel and walked away. Neiring looked over his shoulder to the archives desk. The clerk had disappeared.

Shaken, Neiring left the archives. He reclaimed his weapons and made his way to the prison’s motor dock. Moxley sat behind the driver’s seat of Neiring’s For Official Use vehicle. The detective was sucking on a flavored vapor tube. When he saw Neiring approach, he made as if to move to the passenger side, but Neiring waved him off. Moxley watched as Neiring climbed into the passenger seat.

“Jeez. You okay?” Mox asked him. “You look like somebody punched your grandmother.” He blew a cloud of water vapor.

“Just drive, Mox,” said Neiring. “Get us out of here before I change my mind.”

“About what?”

“About the very stupid things I’m going to do next.”

“I like where this is going,” said Mox.

February 19, 2014

Technocracy: Redefining Innocent Behavior as Racism

My WND Technocracy column this week is about the drumbeat across the Internet and social media to redefine perfectly benign words and deeds as cloaked hatred.

Liberals need to cast you as racist in order to dismiss you. They hate you.

The left uses concepts like “microagressions,” “dog whistles,” and “code words” to tell you what you think.

They want to redefine everything you do, no matter how innocent, as some act of hate and hostility, and in so doing, marginalize you.

Of course, if they could simply murder you instead of dismissing you from the political process, they would do that.

Read the full column here in WND News.

February 13, 2014

Episode 07: “Baycon and Neggs”

[image error]“Daddy?” Annika asked.

Peyton was hunched over the kitchenette table. He was too big to sit on a chair and fit under the table itself, so he sat cross legged on the floor, his elbows and his chin touching the vinyl overlay of the tabletop. He looked up at her. Annika was standing before the printer, waiting for the warmer to open.

“What is it, Annika?”

“I’ve been thinking,” she said.

“You do that a lot.”

She smiled and frowned at him at the same time. He would not have thought it possible had he not seen her do it before. It was as close to exasperation as she got.

“I’m a liability.”

That froze him. He stared at her as she brought her plate from the warmer, placed it on the table, and shoved her chair as close to him as she could. When she climbed into her spot, she poked at her baycon discs and Neggs. Peyton opened his mouth.

“I—” he began.

“You didn’t eat your Neggs,” she said.

“I keep telling you. I don’t like them.”

“Nobody likes Neggs,” said Annika, her tone one of long-suffering tolerance. “Neggs are good for you. Neggs have a full complement of thyroid-proactives that help mitigate background rays from the solar flares.”

“You read that off the box.”

“School,” she said.

Peyton sighed. He wondered how many thyroids he actually had. Turning once more to Annika, he made sure she saw him spear a slippery chunk of Neggs with his fork. He chewed deliberately. She nodded.

“Annika,” he began again.

She knew. His tone told her. “I’m serious, Daddy,” she said. “I’m not fast or strong like you. And I saw on the news. The police patrol these flophouses. They’re the first places they look during Sweeps weeks.”

Peyton frowned. He put his hand on hers; his palm was the size of her breakfast plate. “Then we’ll find someplace else. I’ve been thinking about that.”

“I should go back to school,” said Annika.

That paralyzed him again. He managed to swallow another tasteless hunk of his breakfast. “Do you want to go back to school?” he asked.

She stared at the table. “No,” she said. “I want to stay with you. But I make you less safe.”

Peyton took a deep breath. She did not want to leave him. She was not going to leave him. “I’ve been thinking about the man from the park,” said Peyton. “The man who shared his home with us.”

Annika nodded. “You fixed him,” she said. “Something was wrong with him. Something bad enough that he was on a list.”

She had figured it out, somehow. She knew what he was thinking. “There are lots of people on those lists, Annika,” he said. “All of them very bad people. Very bad people who can’t ever again be trusted. That’s why they’re registered. And that’s why there are lists of exactly where they live.”

“We’ll make them share?”

“Yes,” said Peyton. “If we use the list randomly, if we don’t follow it in order, there will be no way to predict where we might be.”

“But the list makes a pattern,” said Annika. “They could figure it out. Or somebody like Doctor Gorsky could tell again.”

“Annika,” said Peyton, “I spent last night using the wall screen, searching the list. When I told you how many predators the privateer zone has… Even I didn’t realize how many. The police will never have the resources to stake them all out. And they won’t want to try. They might even look the other way, if someone figures out what we’re doing.”

“It’s still a pattern.”

“We’ll alternate with the paid flops, as we’ve been doing,” he said. “Just less. This can work, Annika.”

“Can I have a set of jeweler’s tools?”

Peyton’s jaw fell open. “What on Earth for?”

“So I can take my watch apart,” she said. “I saw a tutorial last night. It looked easy.”

Peyton rubbed one huge thumb on this chin. “You can have any tools that you want,” he told her. “But if you break the watch, it will be, uh, broken.”

“I’m not worried about that,” said Annika. “I can take a computer apart and put it back like it was.”

“You can?”

“School,” she said.

“Oh,” said Peyton.

She pushed her plate away, climbed down, and walked over to sit in his lap. He leaned back so that she would not bang her head on the edge of the table. Before he knew it, she was asleep against his chest. He was not surprised. She had been sleeping strangely, almost without a distinct cycle.

With some difficulty, he managed to push away from the table and stand. Annika, supported under his left arm, weighed nothing. He carried her into the bedroom, put her in the flop’s bed, and arranged the blanket around her. Then he went out. He shut the door carefully.

Without realizing he was doing it, he picked up his plate from the kitchenette. Then he sat in the living area, on the floor in front of the sofa. Nibbling absentmindedly at the cold, rubbery Neggs, he started searching the sex offender registry.

He might go out later if he thought she was sleeping deeply enough. He had taken to walking the alleys of Hongkongtown, trying to clear his head, trying to figure out what to do next. He was not smart like Annika clearly was. His plan was not a brilliant one. It would not sustain them for long.

From his pocket, he pulled the crumpled handbill he had ripped from a utility pole the previous night. It was a plastic sheet bearing his printed image and a lurid list of crimes. “WANTED: REWARD,” it read. “IAN W. PEYTON.”

Annika was no liability.

He was.

February 12, 2014

Technocracy — The Left’s Technological Bludgeon

My WND Technocracy column this week was inspired by Barack Obama’s recent “I can do whatever I want” comments.

Silence, peasants! Her majesty’s dogs are better than you; who are you to question the president and his White House-squatting harpy?

Obama is not a president. He is a lawless dictator, who truly does whatever he wishes. The American public doesn’t give a damn about it, either, because Obama and his fellow Democrats never need fear being voted out of office — no matter how much they disregard the Constitution.

Read the full, depressing column here in WND News.

February 6, 2014

Episode 06: “Three of the Clock”

[image error]“One of the clock,” said Annika. “Two of the clock. Three of the clock.” With each stanza of her little poem, she swung the gold pocket watch on its chain, twirling it around her finger. Peyton smiled down at her.

“‘Of the clock?’” he asked. “Why do you say it like that?”

“That’s what o’clock means, Daddy,” said Annika. “Clock towers used to ring the hour. Sometimes they didn’t even have hands. People didn’t always care about minutes. Things were slower then.”

“I guess they were,” Peyton said, nodding.

“‘Clock’ comes from Latin. The original word meant ‘bell.’”

“Where did you learn that?” Peyton asked.

“School,” she said.

They found the right alley. Peyton led the way to the trash receptacles at its midpoint. Annika made a face and stayed several steps behind him, covering her mouth and nose. He knelt by the metal bin, reached up under, and removed the rag-covered bundle he had stashed there previously.

“Do you want this now?” Annika asked. She had tucked her watch back into the pocket of her sweater and produced the slim length of saw. He had sent her into the little tool shop three blocks over, hoping for a diamond-impregnated blade. This carbide was the best they could do. He would manage.

“Let’s wait until we get a little farther down,” Peyton told her. “Where it’s darkest.”

The streets beyond the alley buzzed with ground traffic and pedestrians. Everyone in Hongkongtown was in a hurry. That was good. People who hurried didn’t see things.

“Smell better?” he asked her.

Annika nodded. She watched, eyes solemn, as he unwrapped the ancient shotgun they had taken from the watch shop. Peyton broke the double-barreled weapon, removed its shells, and closed it again. Then he sawed through the wooden stock. The carbide moved quickly.

“Is it broken?” Annika asked.

“No,” said Peyton. “I’m making it shorter. So I can hide it.” He did not tell her why he had changed his mind about the gun. His metabolism, processing the steady of stream of hormones and other chemicals fed his body by his implanted organs, had mostly healed his gunshot wounds. But the encounter with the police had shaken him. He needed an edge. He needed a weapon.

He had not needed weapons in prison. Big as he had become, he could kill with his his hands more easily than most men could kill with a homemade knife. But this was different. He was back in the world now. He had Annnika to think of.

“I’ll need friction tape,” he said. “For the grip. And it’s going to take a while to trim these barrels. I don’t know where to get more shells. The two we have look new. I hope they don’t blow up the gun.”

Annika looked worried. “Should I stay?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “Do like we talked about. Between these buildings and on the other side is the entrance to the shopping plaza.” He handed her a stack of plastic chits. “We have more cash if you need it.”

“We got a lot for all the watches and phones,” Annika said, smiling.

“Yes,” said Peyton. The chits had come from a robot pawnshop. “Do just like we said. I’ll be right here.”

“Okay, Daddy,” she said.

* * *

Annika walked through the gleaming aisles of the shopping plaza. She was carefully counting in her head — not the poem she sang, which was easy to remember — but the running tally of the merchandise she was buying. She did not want to have to put anything back. That would be rude.

She had selected what seemed a reasonable amount of clothing, as well as a pair of bags to put it in. One was pink and small enough for her to carry. The other was an enormous black duffel, which she could barely manage empty. Daddy would be able to lift that easily.

Clothes for him had been harder. She had checked the size of his boots while he slept, and had managed to find a new pair large enough. His clothing size was another matter. She had nearly given up on finding pants or shirts that could fit him until she stumbled across Exercity.

Exercity was an indoor gym, open to the plaza concourse. Gravity equipment at its entrance was in active use by extraordinarily developed men and women. The women had muscles larger than most of the Hongkongtown men she had seen. They wore very little, to show them off. The men, however, wore form-fitting pants and shirts with special logos on them. None of them were as big as Daddy, but a few were close. She watched for a few minutes until she realized: The clothing stretched. It must be of special fabric meant for exercising.

“Can I help you, princess?” asked a man. His voice was very deep, but cheerful. He smiled through thick, white teeth. His skin was the color of pavement. He looked sweaty. An Exercity badge was pinned to his sleeveless shirt, which was stretched over enormous chest muscles.

“I want to get some of those clothes for my Daddy,” she told him. “For his, uh, for his birthday. He’s very large like you. Do you know where I could get some?”

“We sell them right here in our gift shop, in fact,” he said, smiling more broadly. “Follow me.”

After that, things had been easy. She worked her way through the plaza, mindful of the time, singing her song. “One of the clock, two of the clock, three of the clock,” she whispered. Her watch was safe in her pocket. She checked it now and then.

The robot cart that followed her was a delight. It was like a happy dog, content to stay two paces behind her, waiting patiently while she filled it with nice clothes. The plaza had a crafts and repairs nook that even sold a few tools. She paused there and fixed the salesman with her most adult expression.

“Do you have friction tape?”

The man’s eyebrows went up. “Why, yes, young lady, we do,” he said. “That will be four, please.” He handed her the roll of tape, which was rough like sandpaper. Annika handed him four chits.

“Do you have… Do you have shells?” she asked.

Something changed in the man’s expression. “That would be at the other end of the concourse,” he said. “But there are no sales to minors. Do you have identification? They’ll want to see some.”

She had made a mistake. “No,” she said. “I mean, never mind. Thank you.” She hurried away. She could see him reaching for a phone on the counter of his little shop window.

She walked quickly, forcing the robot to hurry after her. She still had money left, but Daddy hadn’t said she needed to spend it all. They had plenty of clothes. At least she had gotten him his tape. She took out her watch and pressed the button to release the cover. It was less than ten to three.

“Three of the clock,” she told herself. She would need to circle back and take a side corridor in order to leave by the entrance nearest Daddy’s hiding spot. She had taken no more than two steps when a firm hand clamped down on her shoulder.

“Excuse me,” said a woman’s voice. “I’m going to need to read your chip, miss.”

Annika turned and found herself staring into the eyes of a woman in a beige uniform. She had a gun on her hip and a pair of radio glasses on her face. Annika watched her own face in the reflection of the lenses.

“Privateer law,” said Annika, reflexively. Daddy had taught her to say it. “You can’t detain me unless I’ve committed a crime. I’m a free citizen.”

“The shopping plaza is private property,” insisted the security woman. She was younger than she had seemed at first. Close to her, Annika could see how smooth her skin was. She smelled of soap and moisturizer, but not perfume. Annika supposed that if she were a security guard, she would not wear perfume either.

“I’m shopping,” said Annika, pointing to the cart.

“There’s a policy posted at the entrance,” said the guard. “No unsupervised minors. I’m going to need to take you to the office, miss, until we can get hold of your mother or father.”

“No,” said Annika. “Don’t do that.”

The guard’s grip tightened on her shoulder. Annika looked down at the woman’s hand. The guard’s knuckles were white. It made Annika angry. There was no reason to be mean like that.

“You’re coming with me,” said the guard.

Annika looked back up at the guard until the two locked eyes. With her free hand she held out her pocket watch. “Do you see what time it is?” she said.

“So?” the guard asked.

“If I don’t leave here by three of… by three o’clock, my Daddy is going to come in here looking for me.”

“That’s what I want,” said the guard.

“No,” said Annika. “It’s not what you want. Nobody wants that. You’re mean. You don’t have a kind heart. But my Daddy can give you one. You won’t like it.”

The guard stared into Annika’s face. Her grip began to ease. She said, “Look, miss, if you’ve run away from home—”

“You don’t understand,” said Annika emphatically. She looked at the face of the watch, then back to the guard. “In seven minutes my Daddy is going to come here. He’s the largest man you have ever seen. He’s bigger than the people at Exercity. He’s stronger than all of them. And if you make him angry he’ll pull all your arms and legs off.”

The guard started to laugh. As she stared at Annika, the laugh died in her throat. “I don’t—” she started.

“Your arms,” said Annika. “Your legs. Your head.” She reached into the cart, took out the roll of friction tape, and ripped off a piece. “As easily as that. And then when all your blood is on the floor and the ceiling and your head is flat and your teeth are in a pile and your arms are in the disposer, we’ll take what’s in your pockets and you’ll never be mean to anybody else again. Just like Doctor Gorsky.”

With that, Annika wrenched her shoulder free, slapped the robot cart’s override, and nearly ran for the exit with the cart close behind. The guard stared after her, watching her go, making no attempt to interfere.

* * *

Peyton had just finished with the gun when Annika reappeared. He helped her take the bags from the cart. She was unusually quiet, even for her. Finally, he pushed the return button on the robot. It trundled off in the direction of the plaza.

“Did you get everything, Annika?” Peyton asked.

“I couldn’t get your shells,” she said. “But I got the tape.”

Peyton looked surprised. “You don’t need to worry about those things,” he told her.

She looked up at him. He met her gaze and could not interpret her expression. Love? Pride?

“I don’t,” she said.

“Don’t what?” he asked.

“I don’t worry about anything, Daddy.”

February 5, 2014

Technocracy: The Rubber Science Called Climate Change

My WND Technocracy column this week is about the rubber-science that is “climate change.”

If the liberals can agree on anything, it is that proven, successful technologies are bad…

When it’s too cold, too hot, too rainy, not rainy enough, too windy, or the day of the week ends in “y,” the climate change believers tell us that human economic activity must be curtailed for us to survive the coming calamity.

Why do we accept this?

The fact is that normal climate variability is only considered when the weather is inconvenient for liberals (such as when climate change scientists aboard an “adventure” ship get stuck in ice).

Read the full column here in WND News.

January 30, 2014

Episode 05: “Hongkongtown”

Neiring had to pause at the doorway and put his hands on his thighs. His sudden pallor betrayed him; he was close to being sick.

Neiring had to pause at the doorway and put his hands on his thighs. His sudden pallor betrayed him; he was close to being sick.

“I told you,” said Mox.

“I should have believed you,” said Neiring. He took a moment to compose himself, pulled a coffee-stained handkerchief from his pocket, and put it over his face. Then he stuck his head back through the doorway. Mox gave him a shove and sent him in the rest of the way. Neiring speared the private detective with a baleful glance.

“Don’t,” said Neiring.

“Touchy,” said Mox. The private detective was squat, bald, hairy everywhere a man should not be. His bare scalp was pocked. His overcoat and his skin were wrinkled and worn.

Neiring cared about appearances; Neiring knew that his height, at his slender weight, would look awkward if he did not dress well. His uniform was pressed. It was tailored to fit him. The white lettering declaring him a Governmental Inspector was crisp and defined against the blue-black fabric.

“You nearly pushed me into the crime scene, you idiot.”

“Look around you,” Mox said. “You think there’s anywhere you can step that’s not in your precious crime scene?”

Neiring had to admit that the unctuous little man was correct. “Where… Where is the rest?”

“Kitchen,” said Mox. “The head, anyway.”

Neiring pressed the handkerchief more tightly against his face. The walls, the floors, even the ceilings were coated red in whorls of blood. At least where it was thin, it was long dry. Whoever… whatever had done this was long gone.

“How is there this much? Does one man even have this much blood in him?”

“Anybody’s think you’d never seen a man turned inside out,” said Mox. “What are you even doing here, Neiring? This isn’t a government case. We’re still in Hongkongtown, unless they’ve moved the border again.”

“Across the street,” said Neiring. “There was a Seven-A. The death of anybody on the dole requires government oversight.”

“So?”

“So he was murdered, too.” said Neiring.

“This is Hongkongtown,” said Mox. “People get murdered all the time. You honestly think there’s a connection?”

“Yes, people here kill each other like it’s free,” Neiring managed a nod through his handkerchief. “But I don’t believe in coincidence. Not when both men were killed like this.”

“Like what?” Mox said. He grinned. It made his round face look fatter.

“The Seven-A practically had his head ripped off,” said Neiring. “I don’t want to believe there are two people walking around strong enough to do that.” Mox followed him into the kitchenette. A lumpen, bloody mass waited in the sink. “What the hell?” said Neiring.

“Crushed it,” said Mox. “He ripped it off, crushed it, and dumped it in the sink. There’s a couple of legs in the next room. We’re still looking for the arms.”

Neiring coughed so badly into his handkerchief that he saw stars. When he looked up again, Mox was looking smug. “What do you get out of this, Moxley?” said Neiring. “You’ve never lifted a finger that wasn’t financed.”

Mox shrugged. “The victim had a confidential insurance policy. That’s paying for an investigation.”

“Which I’m sure will bear fruit,” Neiring said.

Mox rolled his shoulders once more. “The dead man’ s a number on an anonymous policy. It cashes out when his heart chip says he’s dead. They pay me up front. I give great due diligence.”

“So I’ve heard in the Redlight,” said Neiring. Mox made a rude noise. Neiring pushed past the beaded curtains, checked the… legs… and then backed out into the main room again. “This place has been stripped,” he said.

“Door was open,” said Mox. “Security system smashed. Whatever happened, when it was over, the local scavengers came in, took anything that wasn’t nailed down. Happens all the time. You leave your car out there overnight, government tags or no, they’ll have it gnawed down to the frame by sun-up.”

“Hongkongtown,” said Neiring quietly. “Mox, there’s a local assistance rider in it for you if you give me some departmental cooperation.”

“How much?” Mox put his hand on his nearly invisible chin.

“Standard expenses per day,” said Neiring. “And I’ll buy you lunch when we’re done.” Mox was cheaply bought. Neiring would probably get his money’s worth. “So,” he said. “Do we know who this man was?”

“How would you like to identify him?” Mox asked. “His DNA’s unregistered. You won’t check what’s left of his head against any dental records unless you like puzzles. And you’ve got to have arms to check prints. Arms with fingers attached, which I’m not gonna take for granted if we find them.”

Neiring had to remind himself that Detective Moxley, despite his cultivated appearance to the contrary, was not stupid. He made a slow circuit of the mostly bare room. Even the furniture had been taken, leaving odd silhouettes in the blood coating the room. Only a broken-down sofa had been left behind. It was crusted with dried blood and gobbets of flesh.

The inspector knelt and peered under the sofa. Taking a canister of glove spray from his pocket, he doused his left hand. Then he reached under the sofa and removed a half-crushed pasteboard box.

“What have you got?” asked Mox.

Neiring shook the box, half expecting to find an ear or an eyeball inside. Instead he found three broken phones and a cheap analog watch. There was nothing else. The face of the watch was cracked.

“Not much, as clues go,” said Mox.

“No,” said Neiring. “It isn’t.” He lifted out the watch with his gloved hand. It had a metallic wristband of the type that contracted on springs. From the seams in this he lifted a single, blonde hair, long enough to be shoulder-length.

“Could be from one of the locals. Whoever cleaned this place out,” said Mox. “Think it might be on record?”

“If it is who I think it is,” said Neiring, holding the hair up to the light, “then I’m certain of it.”